Abstract

Rice is a staple food for over half the global population and contributes to more than 10% of global anthropogenic methane emissions. Precise mapping of rice distribution in Asia, the primary region for rice cultivation responsible for over 60% of global production, is crucial for monitoring food security and greenhouse gas emissions. However, due to cloud cover impacts on optical remote sensing imagery, there is still a lack of long-term, high-resolution rice distribution datasets for the entire Asian region. This study develops the Global Crop Dataset-Rice (GCD-Rice) dataset to map rice cultivation across three seasons in 16 Asian countries from 1990 to 2023. Using Landsat and Sentinel-1 datasets, along with a phenological approach and a random forest model, the maps were validated with 258,547 field samples. Results show an average user accuracy of 89.88%, a producer accuracy of 88.52%, and an overall accuracy of 88.85%. Furthermore, comparing with statistical area reveals an overall average R² value of 0.768, a slope of 0.874, and an RMSE of 0.346.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Rice is a vital global crop, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, https://doi.org/10.4060/cd2971en), constituting approximately 8% of the world’s total crop production1. As a staple food for over half the global population, rice plays a crucial role in ensuring food security2,3,4. Rice cultivation requires substantial irrigation, often involving flooding, and thus significantly impacts global freshwater resources5. Furthermore, paddy rice is a major source of anthropogenic methane emissions6, contributing 6% to 30% globally7,8,9,10. The lack of detailed spatial distribution data for rice, however, introduces considerable uncertainty in estimating the spatial patterns of these emissions11,12. Therefore, rapid and precise identification of rice planting locations over large areas is of paramount importance.

Numerous methodologies have been developed for identifying paddy rice planting areas13,14, broadly categorizable into two primary approaches. The first relies on machine learning models15, including U-Net semantic segmentation models16, unsupervised classification17, supervised classification18,19, support vector machines20, and random forests21, to identify rice from remote sensing imagery. While enabling long-term monitoring, machine learning models are constrained by the availability and representativeness of training data22, often necessitating significant investments in manpower, resources, and time for sample collection23. Notably, research by Fu et al. demonstrated that the accuracy of crop classification using machine learning is contingent upon training sample characteristics, with those generated by the time-weighted dynamic time warping (TWDTW) method proving reliable22.

The second category of methods is based on phenological information for rice mapping24. This method generally leverages specific phenological characteristics during the rice growth cycle to differentiate it from other vegetation25,26, enabling large-scale mapping. However, it typically requires a highly temporally continuous sequence of remote sensing images27,28. For instance, Pan et al. employed the TWDTW method to create a 10-meter resolution distribution map of double-season rice in southern China from 2016 to 202029. A specific type of phenological method involves constructing indices using crop-specific signals based on thresholds30,31. For example, Han et al. developed a method using the enhanced vegetation index (EVI), the land surface water index (LSWI), and other parameters, using time-series Sentinel-1 and MODIS data to generate annual rice maps for Southeast Asia and Northeast Asia from 2017 to 201932.

Current research combines phenological methods with machine learning algorithms for crop mapping. For example, Shen et al. used a random forest model to map the long-term series of double-season rice from 1990 to 2023 in China33. This study similarly integrates the advantages of these methods. By using the phenological information of rice and employing the TWDTW method with the statistical area as the threshold, we generate recent-year samples for rice mapping. Subsequently, this extensive sample is used to implement long-term series rice mapping through a random forest model. Rice cultivation is primarily concentrated in Asia, with over 90% of the world’s rice produced in Asian countries1,4. However, existing datasets have several limitations: they do not cover the entirety of Asia16,27; the time range covered is limited, primarily after 201614,18; and they have a medium resolution of 500 meters, resulting in significant mixed-pixel effects. Furthermore, these products do not distinguish between the various seasons of rice cultivation7,14,18.

This study addresses the critical need for spatially explicit mapping of triple-cropping rice systems across Asia through two primary objectives: (1) to develop a long-term series and high spatial resolution distribution map of three-season rice planting in the Asian region by integrating the TWDTW method with the random forest model, and (2) to evaluate the accuracy of this map using statistical data and empirical sample points.

Methods

Study area

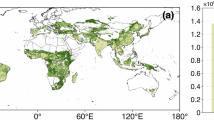

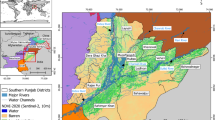

The study focuses on 16 rice-producing countries within the East and South Asian monsoon belt: Pakistan (PAK, ISO country code), India (IND), Nepal (NPL), Sri Lanka (LKA), Bangladesh (BGD), Myanmar (MMR), Thailand (THA), Laos (LAO), Cambodia (KHM), Vietnam (VNM), Malaysia (MYS), Indonesia (IDN), Philippines (PHL), North Korea (PRK), South Korea (KOR), and Japan (JPN) (geographic distribution shown in Fig. 1). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, https://doi.org/10.4060/cd2971en)1, these nations collectively contribute 62.79% of global rice production. China is excluded from this study due to the availability of prior research that has already mapped the distribution of paddy rice within the country29,33,34.

The majority of Asian regions exhibit warm and humid climatic conditions that are highly conducive to rice cultivation. In Southeast Asia, countries typically practice rice farming through 1 to 3 annual growing cycles. THA, with its extensive rice-planting areas, demonstrates this pattern: the major crop is sown from May to August, featuring an extended harvesting period that may persist until December for certain local varieties, while the minor crop is planted in late December and harvested between March and April of the subsequent year. VNM exemplifies a three-cycle system, with spring (January-May), autumn (May-August), and winter (July-November), the latter occupying the smallest cultivation area. Rice cultivation in IDN is predominantly concentrated on the island of Java. Local farmers face challenges due to inadequate cultivation techniques and insufficient water storage infrastructure. Considering the chemical characteristics of the acidic soil and the prevailing agricultural social structure, secondary planting is generally not recommended35.

In Northeast Asia, the agricultural cycle predominantly features a single annual crop. In JPN, rice cultivation is conducted from April to June, followed by harvest activities extending from August through November. In KOR and PRK, rice is planted from May to June and harvested between September and October.

In South Asia, BGD maintains a tri-seasonal rice cultivation system. The Aus (summer) cropping season extends from May to August, utilizing both rainfall and supplementary field irrigation. This is succeeded by the Aman (monsoon) season from June to November, where paddy cultivation predominantly relies on natural precipitation with minimal irrigation requirements. The Boro (winter) cycle, spanning November to April, represents the high-yielding phase necessitating controlled irrigation due to reduced rainfall. Comparatively, IND’s rice cultivation system demonstrates greater complexity, structured around three seasons: summer, autumn, and winter (Table 1).

Agricultural statistical data and validation samples

The agricultural statistics utilized in this study were primarily sourced from the official websites of respective national statistical bureaus. However, for specific countries and years where such data were not publicly accessible, statistics from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/) were employed as an alternative resource. Furthermore, to validate the accuracy of the product, statistical data at the provincial or municipal levels were collected from several countries (Table 2).

In this study, paddy rice samples from various countries were acquired through systematic visual interpretation of high-resolution Google Earth imagery, adhering to the methodological framework established by Shen et al.33. These samples were subsequently employed to construct composite standard time-series lines and perform rigorous accuracy validation of the derived geospatial products.

Identification method

The methodology for paddy rice identification was structured into four distinct phases: (1) preprocessing of remote sensing imagery; (2) identification of paddy rice post-2016, leveraging optical and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery via the TWDTW method; (3) training of a random forest model based on the resultant distribution map; and (4) subsequent identification of paddy rice spanning the period from 1990 to 2023, employing the trained random forest model (Fig. 2). A comprehensive description of the datasets and methodologies is presented in the subsequent sections.

Satellite data and preprocessing

This study utilized satellite data for rice mapping, comprising both optical and SAR images. The optical images were sourced from the Landsat series provided by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and the Sentinel-2 satellite from the European Space Agency (ESA). Data availability from each satellite varied throughout the study period, leading to differences in the specific satellites used. This study incorporated all available satellite data, except for Landsat 7 observations from 2003 to 2011 due to the failure of its scan-line corrector. Paddy rice identification was performed using the shortwave infrared 1 band (SWIR1), with wavelengths of 1.55–1.75 μm (Landsat 5 and Landsat 7) or 1.57–1.65 μm (Landsat 8, Landsat 9, and Sentinel-2). All available satellite-based observations were collected and then aggregated into an 8-day temporal resolution using median values. The SWIR1 reflectance, which is sensitive to soil moisture, has been proven effective for identifying paddy rice26. Additionally, for certain countries (e.g., THA), where the accuracy of rice mapping using only optical imagery is relatively limited, SAR data from the Sentinel-1A satellite were also employed to enhance the mapping process. The time series of vertical-horizontal (VH) polarized backscatter coefficients has demonstrated sensitivity to flood signals during the rice transplanting period29,36. However, because the VH backscatter values of rice partially overlap with those of other crops, and SAR images are susceptible to salt-and-pepper noise26,37, the integration of these two data types followed a specific principle: VH data was utilized only when the results obtained using solely optical image data were of extremely poor quality. In this study, when applying the TWDTW method to identify THA Major and THA Minor, both OA, UA, and PA were low, not exceeding 40%. For the identification of BGD Aman and BGD Aus, OA, UA, and PA were extremely low, not exceeding 20%. The average Slope, RMAE, and R2 for BGD Aman were 0.61, 0.44, and 0.36, respectively. For BGD Aus, these values were 0.39, 1.27, and 0.10, respectively. Therefore, the use of SAR data to assist in these areas also indicated an improvement in accuracy. In this study, the VH time series were obtained and composited to a 12-day temporal resolution using median values.

The preprocessing steps for remotely sensed data in this study differed between the pre-classification and product production stages. During the pre-classification stage, missing values in the optical time series were addressed using linear interpolation, and the time series were smoothed using the savitzky-golay (SG) filter. Additionally, the SAR time series were also filtered using the SG filter. However, Shen et al.33 demonstrated through comparative experimental research that interpolating remote sensing data during the product production phase yields relatively low accuracy, potentially introducing errors into the classification model. Therefore, in the product production stage, this study employed only optical data and did not fill in missing values in the time series.

Time-weighted dynamic time warping

In this study, a phenology-based method, termed the TWDTW method, was employed to pre-classify Asian rice to obtain training samples for subsequent machine learning. The TWDTW method is an enhanced version of the dynamic time warping (DTW) method38,39. The DTW algorithm quantifies the dissimilarity between two nonlinear time series by calculating a distance matrix based on the Euclidean distances between their time points. TWDTW improves upon DTW by incorporating a time weight into the distance matrix, which mitigates excessive stretching or compression of curves to align sequences temporally, thus preserving the seasonal variations of crops. The time weight can be calculated using either a linear or a logistic model. This study adopted the logistic model, which imposes low penalties on minor time distortions while applying higher penalties to larger distortions.

The SWIR1 time series corresponding to the aforementioned ground samples, collected via Google Earth, were subsequently acquired through the google earth engine (GEE) platform. Fifty of these SWIR1 time series were randomly selected and averaged to establish a standard time series for rice in each respective country. The dissimilarity between the time series of each pixel and the standard time series was calculated. When incorporating SAR data, the weighted distance values of VH and SWIR1 for that pixel were computed and subsequently compared with the standard curve. A smaller dissimilarity indicated a higher probability that the pixel represented rice. Statistical rice areas at the country level were then used to determine the dissimilarity threshold; pixels with dissimilarity values below this threshold were classified as rice. The total area of all identified rice pixels was expected to correspond to the statistical rice planting area at the country level.

Given the sensitivity of phenology-based mapping methods to remotely sensed data quality and the inherent challenges in application years with sparse satellite observations, this study strategically confines the methodology implementation to 2016–2023 for rice pre-classification, with consideration given to the proportion of effective observations (Fig. 3).

Random forest algorithm

In this study, we employed the random forest model provided by GEE to generate a rice distribution map spanning the years 1990 to 2023. Initially, 15,000 pixels were randomly selected from rice distribution maps between 2016 and 2023 for model training, comprising 10,000 non-rice pixels and 5,000 rice pixels. The SWIR1 reflectance time series for these selected pixels were subsequently extracted. It is important to note that before 2016, only Landsat imagery was available for classification, resulting in a lower observation density compared to the post-2016 period. To improve the model’s transportability, the training sample was expanded by randomly removing valid values from the time series in the training sets, ensuring the proportion of valid observations matched that of the 1990–2015 period. Ultimately, both the intact training time series and those with removed valid values were input into the random forest model for training, following Shen et al.33. The model was configured using default parameters.

The trained model was employed to predict rice occurrence probability at the pixel scale. National and subnational statistical data (e.g., IND’s state-level records) were integrated to calibrate probability thresholds. To improve spatial consistency and analytical robustness, pixels exhibiting transient planting patterns were excluded, followed by the application of a five-year moving averaging procedure adapted from Shen et al.33. Country-specific rice distribution maps were subsequently generated across the study region.

Existing products

Numerous datasets are available that detail the distribution of paddy rice across various regions of Asia. This study compares our product with two specific datasets: (1) the NESEA-Rice10 dataset32, which generated annual rice maps for Northeast and Southeast Asia from 2017 to 2019 at a 10-meter spatial resolution using a phenology-based method that integrates MODIS and Sentinel-1 data; and (2) the MSEAsia dataset16, which produced a rice map for mainland Southeast Asia in 2019 at a 20-meter spatial resolution utilizing a deep-learning approach based on Sentinel-1 data.

Accuracy assessment

In this study, the accuracy of the product was assessed by comparing it with statistical data and employing validation samples.

A confusion matrix was employed to assess the classification accuracy, calculating the producer’s accuracy (PA), user’s accuracy (UA), and overall accuracy (OA). PA refers to the proportion of correctly classified rice samples among all actual rice samples. UA corresponds to the proportion of correctly classified rice samples among all samples identified as rice. OA reflects the proportion of correctly classified samples among the total number of samples.

This study compared the results with statistical data at the provincial level for IDN, LAO, MMR, PHL, VNM, JPN, KOR, BGD, LKA, and at the municipal level for IND. The comparison included calculating the slope of the regression line, the coefficient of determination (R²), and the relative mean absolute error (RMAE) between the identified area and the statistical data. The RMAE can be calculated as follows:

where SAi and IAi denote the statistical and identified areas of the ith county, respectively, and n represents the total number of counties in the studied province.

Data Records

The dataset of paddy rice distribution in Asia from 1990 to 2023 is available at Science Data Bank40 https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.21665. It is provided in GeoTIFF format with a spatial resolution of 30 meters. The dataset consists of 16 primary folders, each representing a specific country, and secondary folders categorize the data by season. In total, there are 918 GeoTIFF files. This dataset is a component of the global cropland data (GCD) collection and is designated as GCD-Rice. Additionally, the identified areas on rice maps of various countries from 1990 to 2023 are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Technical Validation

Accuracy assessment

Sample points assessment

To assess the accuracy of our dataset (GCD-Rice), we evaluated the rice maps for each season in each country based on samples obtained from Google Earth through visual interpretation. The results, presented in Table 3, indicate that the accuracy of rice distribution in each country is relatively high. The average UA, PA, and OA of all rice identification in Asia are 89.88%, 88.52%, and 88.85%, respectively. Notably, THA, the country with the largest rice cultivation area, exhibits high accuracy, with UA, PA, and OA of 94.74%, 95.10%, and 94.84%, respectively, for its major rice-growing season. Furthermore, the OA of JPN, KOR, LKA Yala, PAK, PRK, KHM, VNM, MMR Main and THA Major exceeds 90%. However, for seasonal rice varieties with smaller planting areas, the UA, OA, and PA are generally lower. For example, the UA, OA, and PA of BGD Aus, BGD Aman, and IND Autumn are all approximately 70%.

Statistical data assessment

To evaluate the identification accuracy of the method used in this study, we conducted a linear regression analysis comparing the agricultural statistical rice area at the provincial or municipal level in each country with the corresponding rice area identified by our approach. As shown in Fig. 4, our method exhibits strong performance in the statistical data assessment. The multi-year average R² value, RMAE, and slope for each country range from 0.540 to 0.973, 0.151 to 0.524, and 0.651 to 0.987, respectively. The overall average R² value, RMAE, and slope are 0.768, 0.346, and 0.874, respectively. Notably, the identification accuracy for MMR, KOR, LAO, THA, and JPN is robust across the three evaluation metrics, with average R² values and slopes exceeding 0.87, and average RMAE values below 0.25. IDN and VNM also perform well, with slopes greater than 0.85 and R² values exceeding 0.78. However, some countries show relatively lower accuracy; for example, the R² values for the PHL and IND are below 0.6, with RMAE values around 0.5.

Spatiotemporal patterns of paddy rice

This study analyzes rice cultivation maps from 16 countries spanning 1990 to 2023, illustrating the spatial distribution of rice cultivation over these 34 years. The rice planting frequency maps of Asia (Figs. 5–8) indicate that rice cultivation is predominantly concentrated in eastern PAK, southeastern IND, BGD, northeastern THA, southern VNM, and Java Island in IDN. Notably, BGD demonstrates a consistently high planting frequency across single-, double-, and triple-season rice cultivation. In IND, the average rice planting frequency in the eastern region exceeds that of the western region. The maximum planting frequency for single-season rice in nearly all countries reaches up to 34 years (Fig. 6). Double-season rice is predominantly cultivated in southern MMR, central and southern THA, as well as southern and northeastern VNM (Fig. 7). Triple-season rice cultivation is limited to specific regions in IND, BGD, and VNM, with most planting frequencies not exceeding 15 years (Fig. 8).

Comparison with existing products

We also compared our rice maps with existing products, as detailed in the Methods section. Using provincial statistical data from various countries, we performed a linear regression analysis on each dataset for the same year within the common study area (Fig. 9). Compared to the MSEAsia dataset16, our dataset exhibited a slightly higher average R² value and a significantly lower RMAE (Fig. 9a1–b1). Notably, the regression slopes for our study consistently exceeded 0.8 across all countries, whereas the slopes for the MSEAsia data varied considerably, ranging from 0.34 in Vietnam to 0.82 in Laos, indicating superior performance of our dataset (Fig. 9c1). In comparison with the NESEA-Rice10 dataset32, the R² values of both datasets were approximately equivalent; however, our study demonstrated a marked reduction in RMAE (Fig. 9a2–b2). Additionally, the regression slopes in most regions for our study were higher than those of the NESEA-Rice10 data (Fig. 9c2). Therefore, based on the linear regression analysis of rice area statistical data and rice identification area, the accuracy of our products has shown a significant improvement.

To demonstrate the accuracy of our dataset (GCD-Rice) in representing the intricacies of rice fields, we conducted a comparative analysis of our rice maps against existing data products using very high-resolution imagery from Google Earth (Fig. 10). Figure. 10a1 through 10a4 display Google Earth images from Myanmar, Thailand, Indonesia, and Japan, respectively. Our maps (Fig. 10a2-d2) effectively captured the locations of rice cultivation in these regions while minimizing the misidentification of non-rice areas, such as rivers and mountains. In contrast, the NESEA-Rice10 (Fig. 10a3-d3) and MSEAsia (Fig. 10a4-d4) datasets failed to provide detailed representations, often blending rice fields or exhibiting significant omissions. Although the NESEA-Rice10 and MSEAsia datasets generally reflect the approximate distribution of rice, their capacity to depict detailed rice field structures is limited, resulting in a significant underestimation of rice cultivation in these areas. Specifically, in Thailand, while the MSEAsia data more accurately reflects rice planting distribution compared to the NESEA-Rice10 data, numerous rice fields remain misclassified (Fig. 10b1–b4). In comparison, our product demonstrates greater consistency and accuracy in spatial representation and detail.

Comparison of this study with two existing products across four regions (MMR, THA, IDN, and JPN), in 2020, 2022, 2019, and 2021, respectively. The first column (a1-d1) consists of high spatial resolution remote sensing images obtained from Google Earth ©. The second to fourth column represent the product produced by this study (GCD-Rice), NESEA-Rice10, and MSEAsia, respectively. Blank panels indicate that the product did not have a classification map for that area.

Uncertainties

Although the rice distribution maps generated in this study demonstrate a high level of accuracy, several limitations must be acknowledged.

Firstly, this study relies on the cropland layer of the land use and land cover change (LUCC) product41, whose classification accuracy introduces uncertainties into our rice mapping process. Potential errors in this dataset may consequently affect the accuracy of our rice maps32. In order to quantify the uncertainty, specifically to determine how much error arises from the LUCC products, we use the rice sample points from the validation sample points mentioned earlier to verify the classification accuracy of the LUCC products. It can be observed that (Table 4) PHL and KHM are more significantly affected by the error propagation from LUCC products compared to other regions, with misclassification rates of 10.119% and 3.883%, respectively. However, the overall average misclassification rate from error propagation is 0.925%.

Secondly, the quality of satellite-based datasets significantly influences classification accuracy25,42,43,44. While previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of generating rice distribution maps using optical and SAR images45,46, the relatively recent launch of the Sentinel-1 satellite on April 3, 2014, has constrained the availability of openly accessible SAR images for long-term rice mapping4,47. Consequently, a substantial body of research has relied on optical remote sensing data, such as Landsat, moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS), and Sentinel-2 imagery4,30,48, for rice mapping. In earlier studies, the phenological approach depended on satellite data with high temporal resolution, which often lacked adequate spatial resolution. As a result, only satellite data with medium spatial resolution, such as MODIS, were deemed suitable for rice mapping27. For instance, Xiao et al.7 employed MODIS remote sensing images to map rice in South and Southeast Asia in 2002 at a resolution of 500 meters. Additionally, acquiring a sufficient number of images during critical rice growth periods poses a considerable challenge in many tropical and subtropical regions49,50. Our analysis of the proportion of high-quality observations from remote sensing data for the periods 1990–2015, 2003–2011 and 2016–2023 (Fig. 3) reveals that the frequency of cloud-free observations during 1990–2015 was relatively low, particularly during 2003–2011, introducing greater uncertainty in rice identification during those years. During 2003–2011, the number of optical data image observations in the study area was relatively lower compared to other years, with the annual observation frequency percentage generally not exceeding 40%. The sparse observational data introduces a degree of uncertainty to the classification result accuracy. We found a positive correlation between the frequency of optical observations and the accuracy of the rice map (Fig. 11). The quality of optical observation explained 18.78% of the variation of mapping accuracy. With the advancement of remote sensing technology, SAR data, optical-radar image fusion data, and spatiotemporal fusion data have gradually been applied to rice mapping, enabling more accurate crop identification in cloudy and rainy regions51,52,53,54,55,56.

Thirdly, statistical data inevitably carries a certain degree of error. The granularity of administrative divisions in statistical data (national, provincial, or municipal level) may introduce discrepancies. For example, in the identification process, differing cultivation practices between the northern and southern regions within a country necessitate separate identification. However, if only the total area of rice cultivation in the country and provincial areas from recent years are obtained, past years’ identification will depend on the known ratio of northern and southern rice cultivation areas based on recent data, which can lead to minor inaccuracies. Additionally, the methods used by various countries to quantify rice cultivation areas may also contribute to statistical errors. Nevertheless, in this study, we use a method that ensures consistency between identified areas and statistical data through a threshold area approach to identify rice cultivation locations, with official statistical data being the sole means to obtain extensive rice cultivation area information across various countries.

Furthermore, complex planting seasons, agricultural practices, or climate factors may pose challenges to rice identification in the region. The Philippines is severely impacted by climate change, with the region experiencing serious and frequent tropical cyclones, floods, droughts, and landslides57. Typhoons during the summer can lead to harmful flooding, and this climatic variability and extreme events contribute to food insecurity in the Philippines58. Secondly, the irrigation systems in the Philippines are designed and operated as continuous flow systems, making it difficult to achieve intermittent wetting and drying of the fields59. This may be confounded by the water management during the rice transplanting period, which is detrimental to the identification of rice. Additionally, farms in the Philippines are typically small, and some indigenous strategies are maintained in the northern mountainous areas, including terracing, crop rotation, and intercropping. Various crop rotation systems and mixed rice practices are implemented in the Philippines60, further complicating the identification of rice. In India, the rice-growing seasons significantly vary across different regions due to factors such as topography, climate, altitude, soil types, and water availability, resulting in a highly diversified agricultural landscape61. This diversity in planting seasons poses substantial challenges for rice location identification in India31. On the other hand, the rice cultivation systems in India are remarkably complex. In Northeast India, locals have maintained traditional agricultural practices, agricultural biodiversity, and knowledge. Differences in agricultural climate, ethnicity, culture, socio-economics, and environment further diversify the agricultural systems in the region62. In the central plains of the Ganges River in the Indian subcontinent, rice-based cropping systems are the most common. The rice-wheat and rice-potato-fallow cropping systems are widely adopted by farmers in this area61. Similarly, the diversification of agricultural systems may also contribute to lower accuracy in rice identification in this region. Additionally, in areas with smaller rice planting areas, it is challenging to identify rice fields as a minority among many other crops, resulting in lower accuracy.

Moreover, several rice distribution maps from 2016 to 2023 generated using TWDTW method for certain countries demonstrate higher accuracy than those produced by the random forest model. These include maps for Thailand Major from 2017 to 2020, North Korea from 2016 to 2022, and South Korea from 2016 to 2022. Therefore, for these specified years and countries, the rice maps generated using the TWDTW method are incorporated into the product instead of those generated by the random forest model.

Code availability

The source code used to generate the rice distribution maps is publicly available at: https://github.com/lishp36/GCD-Rice_codes.

References

FAO. World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2024. https://doi.org/10.4060/cd2971en (FAO, 2024).

Muthayya, S., Sugimoto, J. D., Montgomery, S. & Maberly, G. F. An overview of global rice production, supply, trade, and consumption. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1324, 7–14 (2014).

Bandumula, N. Rice Production in Asia: Key to Global Food Security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., India, Sect. B Biol. Sci. 88, 1323–1328 (2018).

Son, N.-T., Chen, C.-F., Chen, C.-R. & Guo, H.-Y. Classification of multitemporal Sentinel-2 data for field-level monitoring of rice cropping practices in Taiwan. Advances in Space Research 65, 1910–1921 (2020).

Chapagain, A. K. & Hoekstra, A. Y. The blue, green and grey water footprint of rice from production and consumption perspectives. Ecological Economics 70, 749–758 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. Methane emissions from a rice agroecosystem in South China: Effects of water regime, straw incorporation and nitrogen fertilizer. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 93, 103–112 (2012).

Xiao, X. et al. Mapping paddy rice agriculture in South and Southeast Asia using multi-temporal MODIS images. Remote Sensing of Environment 100, 95–113 (2006).

Le Toan, T. et al. Rice crop mapping and monitoring using ERS-1 data based on experiment and modeling results. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 35, 41–56 (1997).

Zhang, X. et al. Sample-free automated mapping of double-season rice in China using Sentinel-1 SAR imagery. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1207882 (2023).

Yadav, S. P. S., Ghimire, N. P., Paudel, P., Mehata, D. K. & Bhujel, S. Advancing effective methods for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions from rice (Oryza sativa L.) fields. J of Sust Agri & Env 3 (2024).

Zhang, B. et al. Methane emissions from global rice fields: Magnitude, spatiotemporal patterns, and environmental controls. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 30, 1246–1263 (2016).

Zhang, G. et al. Fingerprint of rice paddies in spatial–temporal dynamics of atmospheric methane concentration in monsoon Asia. Nat Commun 11, 554 (2020).

Belgiu, M. & Csillik, O. Sentinel-2 cropland mapping using pixel-based and object-based time-weighted dynamic time warping analysis. Remote Sensing of Environment 204, 509–523 (2018).

Dong, J. & Xiao, X. Evolution of regional to global paddy rice mapping methods: A review. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 119, 214–227 (2016).

Xie, D. et al. Cropland Extraction in Southern China from Very High-Resolution Images Based on Deep Learning. Remote Sensing 15, 2231 (2023).

Sun, C. et al. Twenty-meter annual paddy rice area map for mainland Southeast Asia using Sentinel-1 synthetic-aperture-radar data. Zonedo https://zenodo.org/records/7315076 (2022).

Nguyen, T. T. H., De Bie, C. A. J. M., Ali, A., Smaling, E. M. A. & Chu, T. H. Mapping the irrigated rice cropping patterns of the Mekong delta, Vietnam, through hyper-temporal SPOT NDVI image analysis. International Journal of Remote Sensing 33, 415–434 (2012).

Pan, X.-Z., Uchida, S., Liang, Y., Hirano, A. & Sun, B. Discriminating different landuse types by using multitemporal NDXI in a rice planting area. International Journal of Remote Sensing 31, 585–596 (2010).

Du, B. et al. Crop Mapping based on Sentinel-2A NDVI Time Series Using Object-Oriented Classification and Decision Tree Model. Journal of Geo-information Science 21, 740–751 (2019).

Barbosa, R. M. et al. Recognition of organic rice samples based on trace elements and support vector machines. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 45, 95–100 (2016).

Fiorillo, E., Di Giuseppe, E., Fontanelli, G. & Maselli, F. Lowland Rice Mapping in Sédhiou Region (Senegal) Using Sentinel 1 and Sentinel 2 Data and Random Forest. Remote Sensing 12, 3403 (2020).

Fu, Y. et al. Exploring the effects of training samples on the accuracy of crop mapping with machine learning algorithm. Science of Remote Sensing 7, 100081 (2023).

Zheng, Y., Dos Santos Luciano, A. C., Dong, J. & Yuan, W. High-resolution map of sugarcane cultivation in Brazil using a phenology-based method. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 2065–2080 (2022).

Guan, X., Huang, C., Liu, G., Meng, X. & Liu, Q. Mapping Rice Cropping Systems in Vietnam Using an NDVI-Based Time-Series Similarity Measurement Based on DTW Distance. Remote Sensing 8, 19 (2016).

Kuenzer, C. & Knauer, K. Remote sensing of rice crop areas. International Journal of Remote Sensing 34, 2101–2139 (2013).

Shen, R. et al. High-resolution distribution maps of single-season rice in China from 2017 to 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 3203–3222 (2023).

Dong, J. et al. Mapping paddy rice planting area in northeastern Asia with Landsat 8 images, phenology-based algorithm and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sensing of Environment 185, 142–154 (2016).

Dong, J. et al. Tracking the dynamics of paddy rice planting area in 1986–2010 through time series Landsat images and phenology-based algorithms. Remote Sensing of Environment 160, 99–113 (2015).

Pan, B. et al. High Resolution Distribution Dataset of Double-Season Paddy Rice in China. Remote Sensing 13, 4609 (2021).

Luintel, N. et al. Tracking the dynamics of paddy rice cultivation practice through MODIS time series and PhenoRice algorithm. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 307, 108538 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. A High-Resolution Distribution Dataset of Paddy Rice in India Based on Satellite Data. Remote Sensing 16, 3180 (2024).

Han, J. et al. NESEA-Rice10: high-resolution annual paddy rice maps for Northeast and Southeast Asia from 2017 to 2019. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/records/5645344 (2021).

Shen, R., Peng, Q., Li, X., Chen, X. & Yuan, W. CCD-Rice: a long-term paddy rice distribution dataset in China at 30 m resolution. (2025).

Liu, W. et al. A sub-pixel method for estimating planting fraction of paddy rice in Northeast China. Remote Sensing of Environment 205, 305–314 (2018).

Pramudia, A. et al. Strengthening the Agroclimatology Analysis against Local Wisdom Paddy Planting Time at Coastal Area in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 1095, 012027 (2022).

Nguyen, D., Gruber, A. & Wagner, W. Mapping rice extent and cropping scheme in the Mekong Delta using Sentinel-1A data. Remote Sensing Letters 7, 1209–1218 (2016).

Veloso, A. et al. Understanding the temporal behavior of crops using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2-like data for agricultural applications. Remote Sensing of Environment 199, 415–426 (2017).

Maus, V. et al. A Time-Weighted Dynamic Time Warping Method for Land-Use and Land-Cover Mapping. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sensing 9, 3729–3739 (2016).

Dong, J. et al. Early-season mapping of winter wheat in China based on Landsat and Sentinel images. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 3081–3095 (2020).

Li, S. et al. Global Crop Dataset-Rice (GCD-Rice). V1. Science Data Bank. https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.21665 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. GLC_FCS30: global land-cover product with fine classification system at 30 m using time-series Landsat imagery. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 2753–2776 (2021).

Gao, X. et al. A review of paddy rice mapping with remote sensing technology. National Remote Sensing Bulletin 0, 1–27 (2023).

Pei, Z. et al. Rice identification and change detection using TerraSAR-X data. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 37, 151–156 (2011).

You, N. et al. The 10-m crop type maps in Northeast China during 2017–2019. Sci Data 8, 41 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Mapping paddy rice planting area in wheat-rice double-cropped areas through integration of Landsat-8 OLI, MODIS and PALSAR images. Sci Rep 5, 10088 (2015).

Mosleh, M., Hassan, Q. & Chowdhury, E. Application of Remote Sensors in Mapping Rice Area and Forecasting Its Production: A Review. Sensors 15, 769–791 (2015).

Li, P., Feng, Z., Jiang, L., Liu, Y. & Xiao, X. Changes in rice cropping systems in the Poyang Lake Region, China during 2004–2010. J. Geogr. Sci. 22, 653–668 (2012).

Qiu, B., Lu, D., Tang, Z., Chen, C. & Zou, F. Automatic and adaptive paddy rice mapping using Landsat images: Case study in Songnen Plain in Northeast China. Science of The Total Environment 598, 581–592 (2017).

Cai, Y., Liu, S., Lin, H. & Zhang, M. Extraction of paddy rice based on convolutional neural network using multi-source remote sensing data. Remote Sensing for Land & Resources 32, 97–104 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Wang, C., Wu, J., Qi, J. & Salas, W. A. Mapping paddy rice with multitemporal ALOS/PALSAR imagery in southeast China. International Journal of Remote Sensing 30, 6301–6315 (2009).

Sun, Z., Zhou, Q., Yang, P. & Wang, D. Review of crop classification and recognition based on spaceborne polarimetric SAR data. Chinese Journal of Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning 40, 63–71 (2019).

He, Z. & Li, S. Research progress on radar remote sensing for rice growth monitoring. National Remote Sensing Bulletin 27, 2363–2382 (2023).

Haldar, D. & Patnaik, C. Synergistic use of multi-temporal Radarsat SAR and AWiFS data for Rabi rice identification. J Indian Soc Remote Sens 38, 153–160 (2010).

Xu, S. et al. A robust index to extract paddy fields in cloudy regions from SAR time series. Remote Sensing of Environment 285, 113374 (2023).

Fatchurrachman et al. High-Resolution Mapping of Paddy Rice Extent and Growth Stages across Peninsular Malaysia Using a Fusion of Sentinel-1 and 2 Time Series Data in Google Earth Engine. Remote Sensing 14, 1875 (2022).

Torbick, N., Chowdhury, D., Salas, W. & Qi, J. Monitoring Rice Agriculture across Myanmar Using Time Series Sentinel-1 Assisted by Landsat-8 and PALSAR-2. Remote Sensing 9, 119 (2017).

Heckelman, A., Smukler, S. & Wittman, H. Cultivating climate resilience: a participatory assessment of organic and conventional rice systems in the Philippines. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 33, 225–237 (2018).

Stuecker, M. F., Tigchelaar, M. & Kantar, M. B. Climate variability impacts on rice production in the Philippines. PLoS ONE 13, e0201426 (2018).

Miyazato, T., Mohammed, R. A. & Lazaro, R. C. Irrigation management transfer (IMT) and system of rice intensification (SRI) practice in the Philippines. Paddy Water Environ 8, 91–97 (2010).

Magcale-Macandog, D. & Ocampo, L. J. M. Indigenous Strategies of Sustainable Farming Systems in the Highlands of Northern Philippines. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 26, 117–138 (2005).

Soni, P., Sinha, R. & Perret, S. R. Energy use and efficiency in selected rice-based cropping systems of the Middle-Indo Gangetic Plains in India. Energy Reports 4, 554–564 (2018).

Majumder, M., Shukla, A. K., Arunachalam, A. in Biodiversity, Biofuels, Agroforestry and Conservation Agriculture Vol 5 (ed. Lichtfouse, E.) Ch.10 (Springer Netherlands Press, 2010).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Open Research Program of the International Research Center of Big Data for Sustainable Development Goals (Grant No. CBAS2023ORP02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Y., S.L. and R.S. conceptualized and designed the study. R.S. and J.D. developed the method. S.L. generated the dataset, collected the validation data, conducted the statistical analysis, and visualized the results. S.L., R.S., W.Y. and Q.P. wrote the manuscript. W.Y. and R.S. edited and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Shen, R., Jiang, J. et al. A long-term paddy rice distribution dataset in Asia at a 30 m spatial resolution. Sci Data 12, 1052 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05374-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05374-1