Abstract

The discovery of functional materials for energy harvesting and electronic applications require accurate predictions of their optical and transport properties. While several existing datasets contain the optical and transport properties calculated from first-principles calculations, the amount of material entries is often limited and those properties are often reported in scalar form. Comprehensive datasets for the tensorial properties, particularly optical properties, still remain inadequate, which prevents from capturing the anisotropy effect in materials. Therefore, in this work we present the largest-to-date dataset of tensorial optical properties (optical conductivity, shift current) and the dataset of tensorial transport properties (electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, thermoelectric figure of merit zT) for 7301 materials, calculated from the Wannier function method. The quality of the Wannier functions were validated by the maximal spread of the Wannier functions and by the comparison with the band structures from first-principles calculations. These results contribute to the systematic study the functional properties for diverse materials and can benefit future data-driven discovery of candidate materials for optoelectronic and thermoelectric applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The combination of first-principles calculation methods and high-throughput workflow has demonstrated potential in systematically predicting complex material properties and constructing large-scale material databases such as the Materials Project1, JARVIS2, AFLOW3, and C2DB4,5. Those databases significantly accelerate the discovery and screening of functional materials with desirable properties for catalysis6,7, optoelectronics8,9, and quantum defects10,11.

While these existing databases provide well-organized material information, they mainly focused on fundamental properties such as the formation energy, band gap, and thermodynamic stability. Other functional properties that are also commonly used to access the performance of materials in device applications still remain limited. For example, the optical conductivity (the dielectric function) quantifies the linear relation between the induced electric current (polarization) to the shined light of an arbitrary frequency12, which can help to determine the absorption and reflectance of materials and also to reveal the exotic electronic structures in materials such as the topological nodal points and the chirality of materials in experiments13,14. Besides, the shift current response, which is a second-order optical effect, describes the photocurrent generated by the shift of wave functions in non-centrosymmetric materials15,16. As a major component of the bulk photovoltaic effect, it provides an alternative approach to overcome the Shockley-Queisser limit in conventional photovoltaic devices such as the p-n junction17,18. Furthermore, transport properties, such as the electrical conductivity, the thermal conductivity, and the Seebeck coefficient, can characterize the ability of materials to conduct electric and heat currents19; their combination produces the thermoelectric figure of merit (zT) that describes the maximum efficiency of materials to convert heat into electricity20,21,22. Therefore, having a dataset with the above mentioned optical and transport properties can greatly benefit identifying promising materials, including those that have not been well characterized in experiments, for advanced device applications.

Furthermore, since 2018, machine learning models such as graph neural networks have been used to predict various properties of solid-state materials23,24,25,26,27. However, those models have primarily focused on scalar properties such as the formation energy and the band gap23,24,25, and only few were applied to predict spectral properties such as the optical conductivity (as a function of photon frequency)28 or the thermal conductivity (as a function of temperature), even though there already exists established model architecture for sequential target prediction in the machine learning field29,30. This limitation arises from the lack of sufficient high-fidelity data on the spectral properties of materials, which were often required for training deep machine learning models.

While previous attempts were made to construct material datasets with the above mentioned optical and transport properties, those datasets only contain a limited amount of data, with only entries for first-order optical properties such as the optical conductivity and the dielectric function1,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. Besides, these datasets mostly report the properties in scalar form, such as the trace of the optical response tensor only. However, these scalar properties are mostly useful to isotropic materials. For anisotropic materials, the full response tensor for the optical and transport properties are more accurate to assess their performance in experimental setup, because the tensor components are closely related to the space group symmetry and can reflect the directional dependence of the physical responses to external fields39,40,41,42. A notable exception is the work of Ricci et al.43, which provides tensorial transport properties for a large number of materials at different doping levels. However, due to the computational cost, the calculations were performed using a relatively coarse k-point grid, which may affect the numerical accuracy of a small fraction of materials. The scarcity of high-quality tensorial property datasets poses a major challenge for the development of machine learning models. Although recent advances in equivariant graph neural networks have shown potential, in principle, for predicting tensorial properties44, they were rarely studied in practice due to the lack of high-quality tensorial property data, including the second-rank (such as the optical conductivity, electrical conductivity, and thermal conductivity tensors) and third-rank tensors (such as the shift current response tensor). Therefore, the development of reliable datasets for those tensorial spectral properties is essential to the design and application of advanced machine learning models in materials science.

Based on these motivations, in this work we present a database of the tensorial optical and transport properties of 7301 materials calculated from the tight-binding Hamiltonian in the basis of maximally localized Wannier functions. Our high-throughput workflow can automatically choose the projection functions and the optimal energy windows to construct the Wannier functions by analyzing the chemical orbital character of the electronic states near the Fermi level. After excluding the entries whose Wannier functions are not well-localized, we calculated the optical properties as a function of photon energy up to 2.5 eV, including the optical conductivity and shift current response tensor, and the transport properties as a function of temperature which ranges from 100 to 1000 K, including the tensorial electrical conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, thermal conductivity (with only electron contributions), and figure of merit (zT). We applied this workflow to all nonmagnetic elemental and binary materials with less than 20 atomic sites and with band gap less than 1 eV from the Materials Project1, which results in 10142 material entries in our initial set. After excluding those with unconverged relaxation calculations, 9235 entries remain. By further comparing the band structures from first-principles calculations and Wannier tight-binding Hamiltonian and excluding those with mean absolute error (MAE) of the band energy difference greater than 0.05 eV, we finally arrived at 7301 material entries. The average MAE of materials in the final dataset is 0.01 eV, suggesting the high quality of the constructed Wannier functions and the reliability of the calculated optical and transport properties. The presented workflow and dataset serves as a foundation for future data-driven discovery of functional materials and the development of advanced machine learning models for predicting complex material properties.

Methods

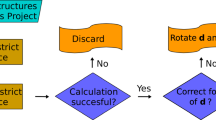

We performed our calculations using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)/6.4.245,46 and the Wannier90/3.1.0 package47, and the overall workflow is shown in Fig. 1.

A schematic plot of the high-throughput computational workflow to calculate tight-binding Hamiltonian and corresponding optical and transport properties. The pink, blue, and green blocks represent the first-principles calculation, automatic Wannierization, and optical and transport property calculation stages.

First-Principles Calculations

To construct our dataset, we first selected all elemental and binary nonmagnetic material entries from the Materials Project1. We excluded the materials with more than 20 atomic sites or with elements heavier than bismuth, and we also restricted to materials with band gap less than 1 eV. For each material entry, we first symmetrized the structure according to the procedure in Ref. 48 and performed several chained first-principles calculations to obtain the ground-state charge density and wave functions, as well as the electronic band structures along the high-symmetry lines for next-step comparison with the band structures calculated from Wannier tight-binding Hamiltonian. At this stage, material entries with unconverged structural relaxations will be excluded.

The first-principles calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package45,46 with projector augmented wave pseudopotentials49,50. We used the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional in the generalized gradient approximation for all calculations51. The kinetic energy cutoff for the plane-wave basis sets is 550 eV. The force convergence threshold is 0.01 eV/Å, and the energy convergence threshold is 10−7 eV. For structural relaxation and self-consistent static calculations, we used the k-point grid with the density of 8 k-points per Å along each Cartesian direction, while for the non-self-consistent calculation we chose the density of 15 k-points per Å along each Cartesian direction. All calculations were spin-unpolarized, since we only selected nonmagnetic materials, and also without the spin-orbit coupling effect. To take account of the strong correlation effect, we employed the DFT+U method52,53, where the U values are adapted from the high-throughput workflow of the Materials Project and summarized in Table 11,54.

Automatic Wannierization

To construct the tight-binding Hamiltonian, we chose the basis of maximally localized Wannier functions, which provide an efficient and physically intuitive representation of the electronic states55,56,57. Since constructing high-quality Wannier functions requires the identification of the leading chemical orbitals as projection functions that contribute to the bands near the Fermi level and the proper choices of the disentanglement and frozen energy windows, we followed the procedure in Ref. 58 by analyzing the total density of states from the static calculations and selecting an energy range [Emin, Emax] which covers the energy range [EF − 2.5eV, EF + 2.5eV], where EF is the Fermi energy. The value of 2.5 eV corresponds to the maximal photon energy in our optical property calculations (see next section), ensuring that the tight-binding Hamiltonian contain all states within this energy range and thus the accuracy of our calculated properties. Besides, we required that the bands within this chosen energy range [Emin, Emax] are separated from other band manifolds, especially the core states and the unphysical states considerably above the Fermi level. Secondly, we analyzed the projected density of states (PDOS) within this energy range [Emin, Emax], and selected the chemical orbitals with the largest relative contribution to the total density of states as the projection functions to construct the Wannier functions. Finally, to choose the optimal disentanglement and frozen energy windows, we scanned the energy values within [Emin, Emax] and selected those which produce the minimal spread of Wannier functions.

The quality of the constructed Wannier functions is mainly characterized by the maximum spread of the Wannier functions, which suggests the extent of localization of the Wannier functions57. In this work, we required that the maximum spread is less than 1.5 × maxi{ai}, where ai is the lattice constant along the Cartesian direction i = x, y, z. Besides, we also accessed the quality of the Wannier functions by comparing the band structures from first-principles calculations with those obtained from the Wannier function method, and we required that the MAE of the band energy difference is less than 0.05 eV. Only materials that satisfy both criteria are selected for subsequent optical and transport property calculations.

Optical and Transport Property Calculations

For the material entries which satisfy the above spread and MAE criteria, we calculated their tensorial optical and transport properties. The optical properties, including the optical conductivity and the shift current, are functions of the photon energy ranging from 0 eV to 2.5 eV; this energy range is generally adequate to detect and validate the exotic electronic structures using experimental techniques such as infrared spectroscopy or spectroscopic ellipsometer13. The optical conductivity tensor σαβ(ℏω)59, and the shift current tensor σαβγ(0; ℏω, − ℏω)60 are calculated as

Here α, β, γ are Cartesian directions, m, n are band indices, fmk and Emk are the Fermi-Dirac occupation and the band energy, \({v}_{nm}^{a}\) is the velocity matrix element, and \({I}_{mn}^{\alpha \beta \gamma }={r}_{mn}^{\beta }{r}_{nm}^{\gamma ;\alpha }\), where \({r}_{mn}^{\alpha }\) is the position matrix element, and \({r}_{nm}^{\gamma ;\alpha }\) is its generalized derivative to kα. Finally, η is the smearing parameter, which is set to be 0.05 eV; this value corresponds to the typical relaxation time of 10 fs in semiconductors and metals61,62.

The transport properties, including the electrical conductivity, the thermal conductivity, the Seebeck coefficient, and the thermoelectric figure of merit (zT), are calculated as functions of temperature ranging from 100 K to 1000 K19,63. Above this temperature range, those transport properties are strongly influenced by disordering effects, such as phase transitions, lattice vibrations, and configurational disorder effect, and may not be relevant for experimental validation. Besides, when calculating the transport properties, we chose the Fermi level as the intrinsic Fermi level from self-consistent calculations; therefore, the reported transport properties correspond to the condition of no chemical doping. We acknowledge that transport properties are strongly dependent on the chemical potential and doping effects; however, it lies beyond the scope of current work and will be addressed in future research. The transport function is defined as

where τ(n, k) is the electron relaxation time. In this work, we adopted the constant relaxation time approximation and set τ = 10 fs, which is the typical relaxation time in metals and semiconductors61,62. More accurate descriptions of the relaxation time in materials involve solving for the electron self-energy through the electron-phonon coupling theory64,65,66,67. However, owing to the significant computational expense associated with the electron-phonon coupling methods in high-throughput calculations, we chose the constant relaxation time approximation in this study as a practical compromise, while acknowledging its limitations in capturing the electron scattering effects.

From the transport function, the kinetic coefficient tensors at different orders \({K}_{n}^{\alpha \beta }(T)\) (n = 0, 1, 2) are defined as

The electrical conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, and the thermal conductivity (with only electron contributions) tensors are calculated respectively as

Finally, we calculated the thermoelectric figure of merit along the three Cartesian directions α = x, y, z only,

The density of the k-point grid for optical and transport properties is chosen to be 100 k-points per Å along each Cartesian direction for materials with one atom in the unit cell and 50 k-points per Å along each Cartesian direction for others. The benchmark results over the k-point density can be found in the Technical Validation section.

Data Records

The dataset is available at Figshare repository68. In the main directory, the “entries.csv” file contains the mp-id of the material in the Materials Project1, the chemical formula, the MAE of the band energy difference (eV), the calculated band gap (eV), and the projections used to generate the tight-binding Hamiltonian. The “INCAR_sample” file is a sample INCAR file with which users can generate the input files for the Wannier90 package47 by modifying the projection functions.

Each subdirectory, with name being the mp-id of the material, contains the crystal structure (“mp-id.dat”) the band structures from first-principles methods (“VASP_bands.dat”) and from Wannier function methods (“wannier_bands.dat”), the real part (“optical_conductivity_real.dat”) and the imaginary part (“optical_conductivity_imaginary.dat”) of the optical conductivity, the shift current (“shift_current.dat”), the electrical conductivity (“electrical_conductivity.dat”), the Seebeck coefficient (“Seebeck_coefficients.dat”), the thermal conductivity (“thermal_conductivity.dat”), and the figure of merit zT (“ZT.dat”), all in the tensorial form.

For the band structures, the high symmetry lines are generated according to Ref. 48, with 20 k-points per line segment. Each block within the band structure files represents a certain band, with the first column being the x-grid for the k-point path, and the second column being the band energies (with respect to the Fermi level). Note that the band structures from first-principles methods contain core electronic states. For optical conductivity and shift current, the first column represents the photon energy, and the remaining columns correspond to the components of the response tensor, as indicated by the file header. For electrical conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, thermal conductivity, and figure of merit zT, the first column represents the temperature, and the remaining columns correspond to the components of the response tensor.

In the dataset, the unit of photon energy is eV, the temperature is K, the optical conductivity is 1/(Ω ⋅ m), the shift current is μA/V2, the electrical conductivity is 1/(Ω ⋅ m), the Seebeck coefficient is V/K, the thermal conductivity is W/(m ⋅ K), and the figure of merit zT is dimensionless.

In Fig. 2, we show the calculated optical conductivity, electrical conductivity, shift current of four material entries (GaAs, InN, AsPd3, BaAs2) in our dataset, where each line represents different tensor components. Note that in this work, we used the primitive cell, instead of the conventional cell, of each material to calculate the optical and transport properties. This could lead to different conventions on the definition of tensor components. For example, the xyz-component of the shift current of GaAs is negative between 0 and 2.5 eV in our work, while when using the conventional cell it is positive60.

Technical Validation

The initial set of materials from the Materials Project, chosen according to the criteria in the Methods section, contains 10142 entries. After excluding those whose relaxation calculations cannot converge, this set restricts down to 9235 entries. Furthermore, by excluding materials whose Wannier functions do not satisfy the spread and MAE criteria, our final dataset contains 7301 entries.

As described in the Methods section, the maximal spread of the Wannier functions and the MAE of the band energy difference between the first-principles calculations and the Wannier function method are two important criteria to validate the quality of the Wannier functions. In Fig. 3(a), we show the ratio of the maximal spread of the Wannier functions with respect to the maximum lattice constant for each material entry (whose relaxation calculations can converge), and 82.1% of the material entries satisfy the criteria for the Wannier function spread (below the read dashed line). On the other hand, the MAE of the band energy differences is shown in Fig. 3(b) and 80.5% of the entries satisfy the criteria for the band energy difference (left to the red dashed line). After combining both criteria, we arrived at 7301 entries, which constitutes 79.1% of the relaxed entries, for our final dataset.

(a) The ratio of the maximal spread to the maximum lattice constants for each material entry, and (b) the MAE of the band energy differences between the first-principles methods and the Wannier function method. The red lines represent our criteria for selecting materials for subsequent optical and transport property calculations.

Furthermore, we randomly selected 18 material entries with MAE smaller than 0.05 eV, and show the calculated band structures from first-principles calculations (black lines) and the Wannier function method (red lines) in Figs. 4 and 5. In Fig. 4, we show material entries where the MAEs are smaller than 0.02 eV; those material entries constitute 66.8% of the 9235 materials whose relaxation calculations converged. The strong agreement between the two methods suggests the effectiveness and the universality of our high-throughput automatic Wannierization workflow. In Fig. 5, we show the band structures material entries where the MAEs are between 0.02 and 0.05 eV. For materials with large MAE, although some inconsistencies are present, they usually occur at energies far above the Fermi level. Since transport properties are relevant to electronic states very close to the Fermi level, we expect that those deviations do not affect the calculated transport properties. Besides, when inconsistencies occur at a strongly localized region in the Brillouin zone, their effect on the calculated optical and transport properties are negligible since those functional properties involve an integration over the Brillouin zone. These results suggest the validity of our criteria based on the MAE of band energy differences.

The comparison of the band structures between the first-principles methods and the Wannier function method, where the MAEs of the band energy differences are smaller than 0.02 eV. The mp-id, chemical formula, and MAE for each entry are listed, and the black and red lines are band structures calculated from the first-principles and the Wannier function method, respectively.

The comparison of the band structures between the first-principles methods and the Wannier function method, where the MAEs of the band energy differences are between 0.02 and 0.05 eV. The mp-id, chemical formula, and MAE for each entry are listed, and the black and red lines are band structures calculated from the first-principles and the Wannier function method, respectively.

Having obtained the high-quality Wannier functions, we proceeded to calculate the optical and transport properties. In Fig. 6, we show the convergence test with respect to the k-point grid. We chose four materials with different number of atoms in the unit cell: Al, GaAs, FeN, and BaAs2, with 1, 2, 2, 18 atoms in the unit cell respectively, respectively. For optical conductivity and electrical conductivity, we show the calculated xx-component. For shift current, due to the space group symmetry, we show the nonzero xyz-component for GaAs and the nonzero xxx-component for FeN and BaAs2. Note that the shift current response vanishes for the centrosymmetric crystal Al. Although we choose our k-point grid for calculating the optical and transport properties by the k-point density, we observe that for materials with small unit cells, a smaller density of 100 k-points per Å is still needed to obtain converged optical and transport properties, while for materials with larger unit cells, convergence is achieved under relatively coarse k-point grid. Therefore, to construct our dataset, we chose the density of 100 k-points per Å (along each Cartesian direction) for material entries with one atom in the unit cell, and 50 k-points per Å (along each Cartesian direction) for the others.

Furthermore, we focus on the MAE of calculated spectrum at various k-point density ρk with respect to the finest density of 100 k-points per Å. Taking optical conductivity σαβ(ℏω, ρk) as an example, we define \(\,{\rm{MAE}}\,=\frac{1}{9{N}_{\omega }}{\sum }_{\alpha \beta }{\sum }_{{\omega }_{i}}| {\sigma }^{\alpha \beta }(\hslash {\omega }_{i},{\rho }_{{\bf{k}}})-{\sigma }^{\alpha \beta }(\hslash {\omega }_{i},100)| \), where Nω is the number of grid points in the photon frequency, and the factor of 9 is the number of components in the optical conductivity tensor. The MAEs of the calculated optical conductivity, electrical conductivity, and shift current of eight selected materials are shown in Fig. 7. The selected materials span both metals and non-metals, various crystal families, and different unit cell sizes, providing a broad representation of the materials in our dataset. As shown in Fig. 7, materials with smaller unit cell sizes, such as Al, require a finer k-point grid to obtain converged results, while for materials with more atoms in the unit cell, such as GeSe, AgO, and BaAs2, convergence can be reached at a coarser k-point grid, justifying our choice of k-point density above.

Finally, we compare our calculated transport properties with previous datasets43. In Ref. 43, the transport properties were calculated through the BoltzTraP package69, which uses the same formalism to calculate the transport properties as the Wannier90 package63. In Fig. 8, we show the comparison of the calculated Seebeck coefficients at 300 K, and we observe overall agreement of the Seebeck coefficients between the two methods. However, Ref. 43 includes doping effects (n-doping for panel (a) and p-doping for panel (b)), whereas our dataset did not include this effect, which explains the deviations between the calculated data.

Usage Notes

The dataset in this work is the largest-to-date collection of systematically calculated optical and transport properties of materials using the Wannier function method. We are expanding the material space to multi-component and magnetic materials, and also using more advanced computational methods such as hybrid functions to correctly describe the electronic properties of materials. The user will be able to utilize the dataset to screen for functional materials with ideal optical and transport properties for experimental verification and machine learning model development.

In this work, we adopted the constant relaxation time approximation and the relaxation time τ = 10 fs was assumed to be a constant scaling factor to all transport properties; the user can scale the transport properties by other values of relaxation time, obtained from experiments or from electron-phonon coupling theory61,62. Note that other work could report the electrical and thermal conductivity divided by the relaxation time43 (the Seebeck coefficient and the figure of merit do not depend on τ).

Besides, when calculating the figure of merit zT, we didn’t consider the lattice contribution to the thermal conductivity, so the reported figure of merit zT is in general overestimated. Especially, for non-metals, the calculated electrical conductivity and thermal conductivity (only electron contributions) are in general small, which could lead to errors in the calculated figure of merit. We expect that after including the lattice contribution to the thermal conductivity, the figure of merit of non-metals will decrease significantly.

Code availability

References

Jain, A. et al. The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Materials 1, 011002 (2013).

Choudhary, K. et al. The joint automated repository for various integrated simulations (jarvis) for data-driven materials design. Npj Computational Materials 6 (2020).

Curtarolo, S. et al. Aflow: An automatic framework for high-throughput materials discovery. Computational Materials Science 58, 218–226 (2012).

Gjerding, M. N. et al. Recent progress of the computational 2d materials database (c2db). 2d Materials 8, 44002– (2021).

Haastrup, S. et al. The computational 2d materials database: high-throughput modeling and discovery of atomically thin crystals. 2d materials 5, 42002– (2018).

Yao, S. et al. Algorithm screening to accelerate discovery of 2d metal-free electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Journal Of Materials Chemistry A 7, 19290–19296 (2019).

Montoya, J. H. & Persson, K. A. A high-throughput framework for determining adsorption energies on solid surfaces. Npj Computational Materials 3 (2017).

Hara, K. O. Discovering low-electron-affinity semiconductors for junction partners of photovoltaic basi2 by database screening and first principles calculations. Journal Of Physical Chemistry C 125, 24310–24317 (2021).

Rosen, A. S. et al. High-throughput predictions of metal-organic framework electronic properties: theoretical challenges, graph neural networks, and data exploration. Npj Computational Materials 8 (2022).

Ferrenti, A. M., de Leon, N. P., Thompson, J. D. & Cava, R. J. Identifying candidate hosts for quantum defects via data mining. Npj Computational Materials 6 (2020).

Wines, D. et al. Recent progress in the jarvis infrastructure for next-generation data-driven materials design. Applied Physics Reviews 10 (2023).

Fox, M.Optical properties of solids. Oxford Master Series in Physics (Oxford University Press, Oxford, [England, 2010 - 2010), second edition. edn.

Xu, B. et al. Optical signatures of multifold fermions in the chiral topological semimetal cosi. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS 117, 27104–27110 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Chiral molecular magnet superstructures with light control. Nano letters 25, 2502–2508 (2025).

Young, S. M. & Rappe, A. M. First principles calculation of the shift current photovoltaic effect in ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 116601, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.116601 (2012).

Tan, L. Z. et al. Shift current bulk photovoltaic effect in polar materials-hybrid and oxide perovskites and beyond. npj computational materials 2, 16026– (2016).

Sauer, M. O. et al. Shift current photovoltaic efficiency of 2d materials. npj computational materials 9, 35–9 (2023).

Dai, Z. & Rappe, A. M. Recent progress in the theory of bulk photovoltaic effect. Chemical physics reviews 4 (2023).

Grosso, G. & Parravicini, G. P. Solid state physics. i–i (Elsevier Ltd, 2014), second edition edn.

Kim, H. S., Liu, W., Chen, G., Chu, C.-W. & Ren, Z. Relationship between thermoelectric figure of merit and energy conversion efficiency. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS 112, 8205–8210 (2015).

Zhou, C. et al. Polycrystalline snse with a thermoelectric figure of merit greater than the single crystal. Nature materials 20, 1378–1384 (2021).

Snyder, G. J. & Snyder, A. H. Figure of merit zt of a thermoelectric device defined from materials properties. Energy & environmental science 10, 2280–2283 (2017).

Xie, T. & Grossman, J. C. Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 145301 (2018).

Fung, V., Zhang, J., Juarez, E. & Sumpter, B. G. Benchmarking graph neural networks for materials chemistry. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 84 (2021).

Reiser, P. et al. Graph neural networks for materials science and chemistry. Commun. Mater. 3, 93 (2022).

Fang, Z. & Yan, Q. Towards accurate prediction of configurational disorder properties in materials using graph neural networks. npj Computational Materials 10, 91 (2024).

Fang, Z. & Yan, Q. Leveraging persistent homology features for accurate defect formation energy predictions via graph neural networks. Chemistry of materials 37, 1531–1540 (2025).

Hung, N. T., Okabe, R., Chotrattanapituk, A. & Li, M. Universal ensemble-embedding graph neural network for direct prediction of optical spectra from crystal structures. Advanced materials (Weinheim) 36, e2409175–n/a (2024).

Lin, T., Wang, Y., Liu, X. & Qiu, X. A survey of transformers. AI Open 3, 111–132 (2022).

Kaur, M. & Mohta, A. A review of deep learning with recurrent neural network. In 2019 International Conference on Smart Systems and Inventive Technology (ICSSIT), 460–465 (2019).

Petousis, I. et al. High-throughput screening of inorganic compounds for the discovery of novel dielectric and optical materials. Scientific Data 4 (2017).

Zhao, J. & Cole, J. M. A database of refractive indices and dielectric constants auto-generated using chemdataextractor. Scientific Data 9 (2022).

Trinquet, V. et al. Second-harmonic generation tensors from high-throughput density-functional perturbation theory. Scientific Data 11 (2024).

Garrity, K. F. & Choudhary, K. Database of wannier tight-binding hamiltonians using high-throughput density functional theory. Scientific data 8, 106–106 (2021).

Cai, Y. et al. High-throughput computational study of halide double perovskite inorganic compounds. Chemistry of materials 31, 5392–5401 (2019).

Hasan, S., Baral, K., Li, N. & Ching, W.-Y. Structural and physical properties of 99 complex bulk chalcogenides crystals using first-principles calculations. Scientific reports 11, 9921–9921 (2021).

Andersen, K., Latini, S. & Thygesen, K. S. Dielectric genome of van der waals heterostructures. Nano Letters 15, 4616–4621 (2015).

Choudhary, K. et al. Computational screening of high-performance optoelectronic materials using optb88vdw and tb-mbj formalisms. Scientific data 5, 180082–180082 (2018).

Kaur, B., Gupta, R., Dhiman, S., Kaur, K. & Bera, C. Anisotropic thermoelectric figure of merit in mote2 monolayer. Physica B: Condensed Matter 661, 414898 (2023).

Barman, N., Barman, A. & Haldar, P. K. First-principles study of anisotropic thermoelectric properties of hexagonal kbabi. Journal of Solid State Chemistry 296, 121961 (2021).

Ibañez Azpiroz, J., Souza, I. & de Juan, F. Directional shift current in mirror-symmetric BC2n. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013263, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.2.013263 (2020).

Saberi-Pouya, S., Vazifehshenas, T., Salavati-fard, T., Farmanbar, M. & Peeters, F. M. Strong anisotropic optical conductivity in two-dimensional puckered structures: The role of the rashba effect. Phys. Rev. B 96, 075411, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.96.075411 (2017).

Ricci, F. et al. An ab initio electronic transport database for inorganic materials. Scientific data 4, 170085–170085 (2017).

Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nature communications 13, 2453–2453 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. An updated version of wannier90: A tool for obtaining maximally-localised wannier functions. Computer Physics Communications 185, 2309–2310 (2014).

Setyawan, W. & Curtarolo, S. High-throughput electronic band structure calculations: Challenges and tools. Computational Materials Science 49, 299–312 (2010).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Anisimov, V. I., Zaanen, J. & Andersen, O. K. Band theory and mott insulators: Hubbard u instead of stoner i. Phys. Rev. B 44, 943–954, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.44.943 (1991).

Cococcioni, M. & de Gironcoli, S. Linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction parameters in the lda + u method. Phys. Rev. B 71, 035105, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.71.035105 (2005).

Jain, A. et al. Formation enthalpies by mixing gga and gga + u calculations. Phys. Rev. B 84, 045115, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.045115 (2011).

Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized generalized wannier functions for composite energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 56, 12847–12865, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.56.12847 (1997).

Souza, I., Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized wannier functions for entangled energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 65, 035109, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.65.035109 (2001).

Marzari, N., Mostofi, A. A., Yates, J. R., Souza, I. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized wannier functions: Theory and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 1419–1475, https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.84.1419 (2012).

Zhang, Z. et al. High-throughput screening and automated processing toward novel topological insulators. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 9, 6224–6231 (2018).

Animalu, A. O. E. Optical conductivity of simple metals. Phys. Rev. 163, 557–562, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.163.557 (1967).

Ibañez Azpiroz, J., Tsirkin, S. S. & Souza, I. Ab initio calculation of the shift photocurrent by wannier interpolation. Phys. Rev. B 97, 245143, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.245143 (2018).

Sernelius, B. E. Intraband relaxation time in highly excited semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 43, 7136–7144, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.43.7136 (1991).

Zhou, Z., Cao, G., Liu, J. & Liu, H. High-throughput prediction of the carrier relaxation time via data-driven descriptor. npj computational materials 6 (2020).

Pizzi, G., Volja, D., Kozinsky, B., Fornari, M. & Marzari, N. Boltzwann: A code for the evaluation of thermoelectric and electronic transport properties with a maximally-localized wannier functions basis. Computer Physics Communications 185, 422–429 (2014).

Claes, R., Poncé, S., Rignanese, G.-M. & Hautier, G. Phonon-limited electronic transport through first principles. Nature Reviews Physics 7, 73–90 (2025).

Park, J., Ganose, A. M. & Xia, Y. Advances in theory and computational methods for next-generation thermoelectric materials. Applied physics reviews 12 (2025).

Ganose, A. M. et al. Efficient calculation of carrier scattering rates from first principles. Nature communications 12, 2222–2222 (2021).

Giustino, F. Electron-phonon interactions from first principles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 015003, https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.89.015003 (2017).

Fang, Z., Hsu, T.-W. & Yan, Q. Database of tensorial optical and transport properties of materials from the wannier function method. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28689059 (2025).

Madsen, G. K. & Singh, D. J. Boltztrap. a code for calculating band-structure dependent quantities. Computer Physics Communications 175, 67–71 (2006).

Ganose, A. M. et al. Atomate2: Modular workflows for materials science. ChemRxiv https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/678e76a16dde43c9085c75e9 (2025).

Rosen, A. S. et al. Jobflow: Computational workflows made simple. Journal of Open Source Software 9, 5995, https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.05995 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Award No. DE-SC0023664. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 using NERSC award BES-ERCAP0029544.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.F. and Q.Y. conceived the experiments. Z.F. wrote the code for the computational workflow and conducted the calculations. T.-W.H. helped with data analysis. Q.Y. supervised the study. The manuscript was written through contributions from all authors, and all authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, Z., Hsu, TW. & Yan, Q. Dataset of tensorial optical and transport properties of materials from the Wannier function method. Sci Data 12, 1092 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05396-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05396-9