Abstract

In the rapidly evolving field of dental intelligent healthcare, where Artificial Intelligence (AI) plays a pivotal role, the demand for multimodal datasets is critical. Existing public datasets are primarily composed of single-modal data, predominantly dental radiographs or scans, which limits the development of AI-driven applications for intelligent dental treatment. In this paper, we collect a MultiModal Dental (MMDental) dataset to address this gap. MMDental comprises data from 660 patients, including 3D Cone-beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) images and corresponding detailed expert medical records with initial diagnoses and follow-up documentation. All CBCT scans are conducted under the guidance of professional physicians, and all patient records are reviewed by senior doctors. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first and largest dataset containing 3D CBCT images of teeth with corresponding medical records. Furthermore, we provide a comprehensive analysis of the dataset by exploring patient demographics, prevalence of various dental conditions, and the disease distribution across age groups. We believe this work will be beneficial for further advancements in dental intelligent treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Dental health has become an increasingly central concern for a growing number of individuals and the whole society, with over 3.5 billion people suffer from oral diseases1. The spectrum of dental diseases extends from commonplace ailments such as cavities and gum disease to more severe conditions like periodontitis2. These issues not only cause significant discomfort and acute pain but can also lead to tooth loss, necessitate complex treatments, and, in severe cases, contribute to systemic infections3. Furthermore, a growing body of evidence suggests a link between oral health and systemic conditions, including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and respiratory infections, underscoring the critical nature of dental health for maintaining general wellness4. Consequently, poor oral health can have a significant societal impact, resulting in lost productivity, increased healthcare costs, and reduced overall well-being.

Addressing a range of dental concerns, from cavities and impacted teeth to dental arch misalignment, requires precise diagnosis and personalized treatment plans. Traditional diagnostic methods, while foundational, often fall short in terms of precision and efficiency5. Relying solely on visual examinations and 2D X-rays can limit the information available to clinicians, potentially leading to missed or delayed diagnoses and suboptimal treatment outcomes. This shortfall can exacerbate patient discomfort and potentially lead to further health complications6. The advent and rapid progression of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in healthcare promise significant improvements in diagnostic accuracy and treatment efficacy7. In the realm of dentistry, AI applications encompass a wide range of tasks, including Image Quality Assessment (IQA), lesion prediction, and automated medical record generation, enhancing early detection capabilities and enabling more accurate interpretations of complex dental conditions8. This transformative potential extends to revolutionizing various aspects of dental care, from early disease detection and personalized prevention to more efficient treatment planning and patient management, ultimately culminating in significantly improved patient care quality and outcomes9,10. For instance, AI-powered image analysis tools are being developed to detect subtle signs of caries or periodontal disease in their early stages, allowing for less invasive and more effective interventions. Moreover, AI algorithms can be used to predict the success rates of different treatment options11, such as dental implants, based on individual patient characteristics and medical history12.

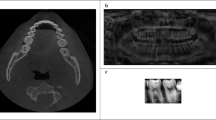

The role of Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) in dental healthcare is particularly noteworthy13. This imaging technology provides a three-dimensional view of teeth, jawbones, and surrounding structures, offering unparalleled detail compared to traditional 2D X-rays14. Currently, dental treatment relies heavily on the on-site judgment of doctors, who diagnose dental diseases by combining medical history and CBCT images after consultation, thus prescribing the correct treatment plan. Given the variation in clinical diagnostic methods and the reliance on follow-up records for tooth diagnosis, employing an effective AI-driven application has the potential to streamline the consultation process, reducing the rate of misdiagnosis and enhancing diagnostic consistency15. However, the development and validation of robust AI models necessitate access to high-quality, well-annotated multimodal datasets, particularly those incorporating both CBCT images and comprehensive medical records. A major difficulty is acquiring data from medical institutions16, a process that has not received sufficient attention in the field. Medical institutions often have strict data privacy and sharing policies, making it challenging to access the data. Moreover, the associated costs of acquiring high-quality expert medical records are high. These records need to be carefully reviewed and annotated by experienced healthcare professionals, which requires substantial time and resources.

A review of the currently published literature reveals a scarcity of publicly accessible CBCT datasets specifically designed for dental AI research. As illustrated in Table 1, the majority of readily available datasets primarily consist of 2D X-ray images. While these datasets have significantly contributed to advancements in dental image analysis techniques, the inherent two-dimensional nature of these data limits their applicability for tasks requiring comprehensive three-dimensional anatomical information6. Furthermore, as summarized in Table 2, existing multimodal datasets, though incorporating additional modalities like gaze maps, audio-text data, or intraoral scans, often lack the comprehensive medical context provided by expert annotations and detailed patient records. Notably, the lack of detailed medical records restricts the development of AI applications requiring a holistic understanding of patient health17. These limitations underscore the critical need for a high-quality multimodal dataset18, encompassing both 3D CBCT images and extensive medical documentation, to accelerate progress in dental AI research19.

To address these limitations and empower advancements in dental AI research, we introduce MMDental20, a novel multimodal dataset encompassing 3D CBCT images and comprehensive expert medical records from 660 patients. Recognizing the need for more insightful analyses beyond basic statistics, we delve deeper into the MMDental dataset to uncover valuable patterns and characteristics. Unlike existing datasets that primarily focus on providing raw data, MMDental stands out by including meticulously curated patient data, including comprehensive treatment notes, follow-up records, and patient-reported outcomes. This rich dataset allows us to conduct a detailed investigation of disease prevalence and its distribution across different age groups, a critical aspect often overlooked in previous research21. By analyzing these distributions, we provide insights that can inform the development of age-adaptive diagnostic tools, enabling more precise diagnoses and personalized treatment recommendations. For instance, understanding how the prevalence of specific conditions varies with age can help researchers develop AI models that account for these differences, leading to improved accuracy and personalized care22. Furthermore, this analysis offers valuable information for model selection and training, guiding researchers towards the most suitable AI approaches for tasks such as automated diagnosis, risk prediction, and prognostication. We believe that the public availability of MMDental and our comprehensive analysis will significantly accelerate progress in intelligent dental care by providing both a valuable data resource and a deeper understanding of dental health trends.

Methods

The formulation of MMDental follows a structured four-stage workflow, as depicted in Fig. 1 The first stage, Data Collection, focuses on gathering CBCT images and corresponding medical records from a diverse patient population at Hangzhou Dental Hospital. This stage involves implementing robust procedures for patient recruitment, obtaining informed consent, and ensuring ethical data handling in accordance with international guidelines. Next, Data Preprocessing aims to convert the raw CBCT and medical record data into standardized formats suitable for analysis and processing. This includes carefully aligning data from different sources, conducting thorough quality control checks, and performing expert reviews to guarantee data accuracy and completeness. Privacy Cleaning and Renaming safeguards patient privacy and ensures ethical compliance through robust anonymization procedures. All personally identifiable information is removed from both the CBCT images and medical records through file renaming and data re-encoding using unique identifiers. Finally, Data Organization combines the anonymized and processed data into a well-structured, user-friendly format for dissemination to the research community. This includes uploading the unified multimodal dataset to a publicly accessible repository. Each stage of the MMDental dataset construction process is elaborated upon in detail in the following subsections.

Data Collection

All data in the MMDental dataset are collected from Hangzhou Dental Hospital, encompassing a total of 161,200 3D CBCT slices and 2,125 expert medical records from 660 patients, ranging in age from 5 to 86 years old. Within this dataset, 403 patients have both 3D CBCT images and corresponding detailed medical records, including initial diagnoses and follow-up documentation. An additional 257 patients contribute solely to expert medical records in the dataset.

Participant Recruitment and Ethical Considerations

The study recruits patients with diverse dental concerns. This approach ensures the dataset represents a wide range of dental conditions and demographics. The inclusion criteria encompass individuals of all ages seeking dental diagnostic evaluation or treatment planning at the hospital. The exclusion criteria include patients with contraindications to CBCT imaging, such as pregnancy or severe claustrophobia.

Prior to enrollment, all potential participants receive a thorough explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Each patient provides written informed consent, explicitly authorizing the use of their anonymized data for scientific research purposes. Minors will have the informed consent form signed on their behalf by their guardian, who must be fully informed and provide consent. The guardian who is informed and signs the consent form must be the patient’s parent, and the relationship between the guardian and the minor patient (e.g., father-daughter, mother-daughter, father-son, or mother-son) should be clearly stated in the informed consent form.The hospital assures strict confidentiality of their personal information in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and adheres to international guidelines for human biomedical research and quality management rules for drug clinical trials.

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Lishui University (approval identification number: 2022YR014). The committee also approved the open publication of the anonymized dataset under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license, ensuring that all ethical guidelines and privacy protections were strictly adhered to.

CBCT Image Acquisition

Before conducting a thorough examination of the oral cavity, physicians perform in-depth assessments that cover the patient’s chief complaints, along with their past and present medical histories. This comprehensive clinical evaluation is crucial in determining the necessity and appropriateness of Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) imaging for each patient. The decision to proceed with CBCT is based on several factors, including the suspected dental condition, the need for detailed 3D anatomical information for accurate diagnosis or treatment planning, and ensuring there are no contraindications to using CBCT.

When indicated, CBCT scans are performed using one of two advanced machines:

-

HiRes 3D-Plus (Beijing Langshi Instrument Co., Ltd.): This machine is equipped to deliver high-resolution three-dimensional images with a size of 640 × 640 × 400 voxels, featuring a focus size of 0.4 (IEC60336), a 3D slice resolution of 640 × 640 pixels, a spatial resolution of 1.8 lp/mm, an emission laser wavelength of 635 ± 20 nm, and a slice thickness of 0.25 mm.

-

Oral and Maxillofacial CBCT Equipment (Changzhou Boen Zhongding Medical Technology Co., Ltd.): This machine is equipped with identical specifications to the HiRes 3D-Plus to deliver high-resolution three-dimensional CBCT images.

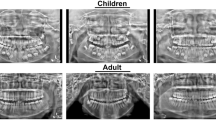

Scanning parameters are specifically adapted to the demographics of each patient. For normal-bodied adults using the HiRes 3D-Plus, the selected settings are 100 kV and 4 mA. Minors receive a reduced current of 3 mA at the same voltage to decrease radiation exposure. The Boen machine’s parameters vary further; children are scanned at 90 kVp and 6 mA, while elderly and adult males are scanned at 90 kVp and 9 mA, and adult females at 90 kVp and 8 mA. These adjustments ensure optimal image quality with minimal radiation exposure tailored to individual patient needs.

Experienced physicians supervise the imaging process, guiding patients to align properly with the machine. This ensures comprehensive coverage of the entire dental arch and bilateral temporomandibular joints (TMJs) within a standard 16 × 10 field of view. During the scan, patients are instructed to bite down firmly, avoid swallowing saliva, and remain still to prevent image blurring. Any CBCT scans that do not meet the required quality standards are discarded. The procedure is repeated to guarantee the acquisition of diagnostic-quality images. All obtained CBCT data is stored in DICOM format for further analysis and processing.

Medical Record Acquisition

The clinical data of medical records are sourced from the Hangzhou Dental Outpatient Management System, ensuring each patient’s CBCT images are accompanied by detailed clinical information. The medical records encompasses a wide range of data, including:

-

Filename: A unique numerical identifier corresponding to the associated CBCT image file, ensuring patient anonymity and data consistency across modalities.

-

Sex: Patient’s biological sex, recorded as “male” or “female.”

-

Age: Patient’s age at the time of the initial consultation, recorded in years.

-

Main Appeal: The primary reason for the patient’s visit to the dental clinic, captured verbatim from the patient’s initial complaint.

-

Subsequent: Details of any subsequent visits or follow-up consultations, including dates, reported symptoms, and reasons for seeking additional care.

-

Present Medical History: A comprehensive account of the patient’s current medical conditions, including any relevant systemic illnesses, medications, or allergies.

-

Past Medical History: A summary of the patient’s past medical history, capturing any prior illnesses, injuries, or surgeries that might be relevant to their dental health.

-

Oral Check: A detailed description of the findings from the dentist’s oral examination, including the condition of teeth, gums, and other oral tissues.

-

Diagnosis: The official diagnosis made by the dentist using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) coding system, identifying the specific dental condition(s) being addressed23.

-

Treatment Plan: The recommended course of treatment, outlining proposed procedures, expected timelines, and any alternative treatment options considered.

-

Handle: A record of the specific procedures and interventions performed during the patient’s visit, including details of medications, materials, and techniques used.

-

Doctor Advices: Specific post-treatment instructions and advice given to the patient, including recommendations for oral hygiene practices, medications, and follow-up care.

These records, originally in PDF format, are systematically extracted and converted into a structured .CSV format for analysis and further processing. The medical record dataset also includes follow-up data, providing a comprehensive view of each patient’s dental health trajectory.

Data Summary

Our MMDental includes CBCT images and medical records, with each patient’s CBCT provided as a separate .nii.gz file, and medical records for all patients together in a .csv file. Each record in the CSV file is structured to include a unique identifier for patient consistency across initial visits and subsequent follow-ups, gender, and age, providing a basic demographic snapshot. The dataset encompasses detailed patient interactions, starting from the main complaint that prompted the dental visit, followed by any subsequent visits, thus tracing the patient journey through the healthcare system. It includes both present and past medical histories to offer a complete medical backdrop against which dental conditions are evaluated. Oral examination outcomes are documented to outline the immediate oral health status, leading to the professional diagnosis that pinpoints the specific dental condition being addressed. The treatment plan delineates the proposed care approach, while the management column captures the practical steps taken during patient care. Additional notes are included to allow for the recording of nuanced information that might not fit neatly into the other categories.

Data Processing

In the data processing stage of our MMDental dataset, a series of rigorous steps are undertaken to ensure the dataset’s accuracy, confidentiality, and adherence to ethical standards. Initially, we manually align each patient’s CBCT images with their corresponding medical records, carefully correlating names and record dates using the DICOM format for CBCT data with the original PDF format for medical records. This is followed by a thorough review by a team of five nurses to verify the accuracy and consistency of the initial multimodal dataset.

Subsequently, two senior dental experts independently examine the dataset with the following objectives:

-

Confirm the correctness of the medical records: This involves checking for any inconsistencies, errors, or missing information within the clinical data.

-

Ensure the absence of misdiagnoses: The experts scrutinize each patient’s diagnosis to ensure it is consistent with the clinical findings and imaging data.

-

Refine and supplement medical records as needed: When necessary, the experts add further details or clarifications to the medical records, ensuring the dataset is as comprehensive and informative as possible.

Following the expert review, we convert the CBCT data from DICOM (.dcm) format to NIFTI (.nii.gz) format for improved compatibility with neuroimaging analysis tool. We then utilize Baidu’s OCR toolkit to convert the medical record text data from PDF format to CSV format, consolidating all patient records into a single Excel file for efficient processing. A pivotal step in the process is the anonymization of the data to protect patient privacy. For the CBCT images in NIFTI format, we re-code the file names using unique numerical identifiers, ensuring the removal of any traces of personal patient information. Additionally, we meticulously examine each data file to ensure the absence of any additional metadata containing patient privacy information. Similarly, for the medical record CSV data, all personal information within the files is digitally re-encoded using numerical identifiers, guaranteeing complete re-identification while maintaining consistency with the corresponding NIFTI file names. A dedicated team conduct rigorous reviews of both datasets to guarantee the complete removal of any identifiable information. Subsequent data cleaning steps involves deleting duplicate CBCT images, retaining only the original and correct scans. In our MMDental dataset, we specifically focus on initial consultation CBCT data. This decision is based on the rationale that initial consultations typically provide the most comprehensive and unbiased representation of the patient’s dental condition, as subsequent scans may be influenced by ongoing treatments or interventions. Finally, a team of seven doctors performs a comprehensive matching and verification of the CBCT and medical record datasets to form the final MMDental multimodal dataset.

Data Records

The MMDental dataset is publicly available on Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28505276)20. The dataset is organized into folders, with each folder containing the CBCT data files for an individual patient. Filenames for the CBCT data are composed of unique numerical identifiers to maintain patient anonymity. A separate CSV file named ‘medical_records.csv’ contains the corresponding medical record information for all patients. This file includes 12 columns with the following headers: filename, sex, age, main appeal, subsequent, present medical history, past medical history, oral check, diagnosis, treatment plan, handle, and doctor advices. Similar to the CBCT data files, the “filename” column in the CSV file uses unique numerical identifiers that match the corresponding CBCT data file for each patient. The tooth notation system used within the CSV file is the FDI World Dental Federation notation, which has been systematically translated from the original PDF medical records for consistency and ease of analysis.

Technical Validation

Quality control and validation are integral to ensuring the reliability and robustness of the MMDental dataset for AI-based research. To achieve this, we systematically characterized the dataset across critical variables such as sex, age, and disease categories. This process ensures the dataset’s distributions are representative of the target population and suitable for the intended research applications. Statistical assessments are performed to confirm the appropriateness and balance of these distributions, establishing a solid foundation for the development and evaluation of AI models.

CBCT Image Quality Control

CBCT scans are assessed for diagnostic quality based on pre-defined criteria including clarity, absence of artifacts, anatomical completeness, and full coverage of the dental arch and temporomandibular joints (TMJs). Scans not meeting these criteria are excluded. Experienced physicians supervise image acquisition, ensuring proper patient positioning to minimize motion artifacts. While precise quantification of rejected scans is unavailable due to the retrospective nature of data collection, this rigorous process ensured inclusion of only high-quality images. The use of two different CBCT machines (HiRes 3D-Plus and Oral and Maxillofacial CBCT Equipment) with identical specifications minimize inter-device variability. Scanning parameters are tailored to individual patient demographics (age, sex) to optimize image quality and minimize radiation exposure.

Medical Record Validation

Medical records are validated through a multi-step process. Initially, five nurses review each record for completeness and internal consistency. Subsequently, two senior dental experts independently examine the records, using the corresponding CBCT images as a reference, to verify diagnostic accuracy, supplement missing information (e.g., clarifying ambiguous descriptions, adding details from supplementary clinical notes, correcting potential inconsistencies between clinical findings and imaging data), and ensure comprehensive documentation. Discrepancies between expert findings are resolved through discussion and consensus. The use of standardized terminologies—ICD codes for diagnoses and FDI World Dental Federation notation for tooth identification—ensured consistency and facilitated analysis. This meticulous, CBCT-aided review process significantly enhanced the accuracy and reliability of the medical record data.

Limitations

While the MMDental dataset offers a significant resource for multimodal dental AI research, several limitations exist. As a single-center dataset collected from Hangzhou Dental Hospital, generalizability to other populations may be limited. Despite comprehensive inclusion criteria designed to capture a diverse patient cohort, the demographic and clinical characteristics of the included patients may not fully reflect the global diversity of dental conditions and treatment approaches. Furthermore, the retrospective nature of the data collection precluded precise quantification of the number of CBCT scans excluded due to quality control procedures. Future research could address these limitations by incorporating data from multiple centers and diverse geographic locations.

Dataset Characteristics

Patient Demographics

The MMDental dataset comprises 660 patients with ages ranging from 5 to 86 years (mean ± standard deviation: 38.60 ± 16.56 years), ensuring a broad demographic representation. This wide age range enhances the dataset’s applicability across diverse patient populations. The dataset also demonstrates a balanced sex distribution (51.06% male, 48.94% female), which helps mitigate sex-related biases in AI model development and evaluation.

To further examine potential differences between patients who have only medical records (“Only Record”) and those who also have CBCT imaging (“Record+CBCT”), we present the age distribution for both cohorts, as well as for the combined set of all patients, in Fig. 2. These violin plots illustrate density estimates along with medians and interquartile ranges for male and female patients. Overall, the female age distributions are comparable between the Only Record and multimodal groups, while the male distributions exhibit a slightly higher median in the multimodal subset. Nonetheless, the broad overlap in age ranges across both cohorts suggests that combining them remains appropriate for most analyses, especially given the robust sample size and balanced sex ratio.

Age distributions for male (orange) and female (green) patients in the “Only Record,” “Record+CBCT,” and “All Patients” groups, presented as violin plots. The width of each violin indicates the density of patients at each age, with the median age marked by a white dot. The red dashed lines denote the quartiles (25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles), and the accompanying numbers indicate the corresponding ages.

Disease Prevalence

The prevalence of dental conditions within the MMDental dataset is systematically analyzed to assess its clinical relevance and applicability to AI-driven research. Our comprehensive distribution aligns with large-scale epidemiological studies on dental health. According to a global systematic review by Kassebaum et al., dental caries and tooth loss remain significant global health challenges, which is reflected in our dataset’s high proportion of “Damaged or Missing Teeth” at 22.62%24.

Figure 3 provides a detailed visualization of the dataset’s sex distribution (51.06% male, 48.94% female) and the relative frequencies of eight commonly diagnosed dental conditions using a donut chart. The condition distribution demonstrates remarkable concordance with population-based studies. A comprehensive study by Peres et al. highlighted the global prevalence of oral conditions, supporting the significance of conditions like pulpitis and caries that represent substantial proportions in our dataset1.

Distribution of dental diseases and patient sex in the MMDental dataset. The donut chart illustrates the proportion of patients diagnosed with each of the eight dental conditions. The size of each segment corresponds to the percentage of patients with that specific condition, and the exact values are provided along with the condition name. The inner circle of the donut chart depicts the sex distribution within the dataset, with blue representing females and red representing males.

Moreover, the inclusion of less prevalent but clinically significant conditions such as Apical Periodontitis (9.22%) and Periodontitis (8.06%) reflects the dataset’s comprehensive nature. A population-based study by Eke et al. emphasized the importance of capturing these conditions, which often represent critical diagnostic challenges in dental healthcare25.

The diverse representation of dental conditions, ranging from Impacted Tooth (13.61%) to Gingivitis (10.47%), underscores the dataset’s alignment with real-world clinical scenarios. This comprehensive approach enhances its representativeness and utility for training and validating AI models in dental diagnostics.

Age-Related Disease Distribution

The age-related distribution of dental conditions is analyzed to validate the dataset’s ability to capture age-specific disease patterns, which is crucial for developing age-adaptive AI tools. Figures 4, 5, and 6 present stacked horizontal bar charts illustrating the prevalence of eight dental conditions across four distinct age groups (0-24, 25-32, 33-50, and 51-86 years) in the “Only Record,” “Record+CBCT,” and “All Patients” cohorts, respectively. The proportions of various dental conditions remain notably consistent across these three subsets. Younger patients (0-24 years) frequently present with pulpitis and impacted teeth, whereas the 25-32 age group is predominantly diagnosed with impacted teeth and caries. In the 33-50 age group, damaged or missing teeth become more prevalent, a trend that continues in individuals over 50 years, where periodontitis also emerges as a significant condition. This consistent pattern across cohorts underscores the reliability of the dataset in capturing age-specific disease distributions, thereby supporting robust, age-adaptive AI model development and evaluation.

Distribution of dental conditions across different age groups (Only Record cohort). The stacked horizontal bar chart displays the prevalence of eight common dental conditions in the Only Record cohort. Each colored segment represents the number of patients diagnosed with the corresponding condition within each age group (0, 24], (24, 32], (32, 50], and (50, 86]. The numerical values within each segment indicate the specific number of patients affected.

Distribution of dental conditions across different age groups (Record+CBCT cohort). The stacked horizontal bar chart displays the prevalence of eight common dental conditions in the Record+CBCT cohort. Each colored segment represents the number of patients diagnosed with the corresponding condition within each age group (0, 24], (24, 32], (32, 50], and (50, 86]. The numerical values within each segment indicate the specific number of patients affected.

Distribution of dental conditions across different age groups (All Patients cohort). The stacked horizontal bar chart displays the prevalence of eight common dental conditions in the entire patient cohort. Each colored segment represents the number of patients diagnosed with the corresponding condition within each age group (0, 24], (24, 32], (32, 50], and (50, 86]. The numerical values within each segment indicate the specific number of patients affected.

Usage Notes

The MMDental dataset described in this paper can be downloaded through the link mentioned before. Users should properly cite this article and acknowledge the contributions in their study.

Code availability

All codes for the creation of this dataset are open-source. The OCR conversion of the original PDFs to CSV format is performed using the Baidu AI Cloud platform. The neuroimaging analysis tool for CBCT data formant conversion is dicom2nifti. (https://github.com/icometrix/dicom2nifti).

Change history

05 August 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05709-y

References

Peres, M. et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. The Lancet 394, 249–260, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8 (2019).

Kinane, D. F., Stathopoulou, P. G. & Papapanou, P. N. Periodontal diseases. Nature reviews Disease primers 3, 1–14 (2017).

Li, X., Kolltveit, K., Tronstad, L. & Olsen, I. Systemic diseases caused by oral infection. Clinical microbiology reviews 13(4), 547–58, https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.13.4.547-558.2000 (2000).

Kapila, Y. Oral health’s inextricable connection to systemic health: Special populations bring to bear multimodal relationships and factors connecting periodontal disease to systemic diseases and conditions. Periodontology 2000 87, 11–16, https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12398 (2021).

Najumnissa, D. Comparison and analysis of dental imaging techniques. Computational Techniques for Dental Image Analysis https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-6243-6.CH008 (2019).

Song, W., Liang, Y., Yang, J., Wang, K. & He, L. Oral-3d: Reconstructing the 3d structure of oral cavity from panoramic x-ray. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 35, 566–573, https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v35i1.16135 (2021).

Fogel, A. & Kvedar, J. Artificial intelligence powers digital medicine. NPJ Digital Medicine 1, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-017-0012-2 (2018).

Hosny, A., Parmar, C., Quackenbush, J., Schwartz, L. & Aerts, H. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nature Reviews Cancer 18, 500–510, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-018-0016-5 (2018).

Shan, T., Tay, F. R. & Gu, L. Application of artificial intelligence in dentistry. Journal of Dental Research 100, 232–244, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034520969115 (2020).

Khanagar, S. et al. Developments, application, and performance of artificial intelligence in dentistry - a systematic review. Journal of Dental Sciences 16, 508–522, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2020.06.019 (2020).

Sun, B., Liu, Z., Wu, Z., Mu, C. & Li, T. Graph convolution neural network based end-to-end channel selection and classification for motor imagery brain–computer interfaces. IEEE transactions on industrial informatics 19, 9314–9324 (2022).

Tang, Z. & Chang, T.-H. Fedlion: Faster adaptive federated optimization with fewer communication. In ICASSP 2024 - 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 13316–13320, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP48485.2024.10447045 (2024).

Scarfe, W. C., Farman, A. G. & Sukovic, P. et al. Clinical applications of cone-beam computed tomography in dental practice. Journal-Canadian Dental Association 72, 75 (2006).

Baumgaertel, S., Palomo, J., Palomo, L. & Hans, M. G. Reliability and accuracy of cone-beam computed tomography dental measurements. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics 136 1, 19–25; discussion 25–8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.09.016 (2009).

Cui, Z. et al. A fully automatic ai system for tooth and alveolar bone segmentation from cone-beam ct images. nat commun 13: 2096 (2022).

Feng, X. et al. Fdnet: Feature decoupled segmentation network for tooth cbct image. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 1–5 (IEEE, 2024).

Adibi, S. S. et al. Medical and dental electronic health record reporting discrepancies in integrated patient care. JDR Clinical & Translational Research 5, 278–283, https://doi.org/10.1177/2380084419879387 (2020).

Chen, Z., Gao, C., Li, T., Ji, X. & Liu, S. Open access dataset integrating eeg and fnirs during stroop tasks, figshare (2023).

Bk, C. Dental records: An overview. Journal of Forensic Dental Sciences 2, 5–10, https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2948.71050 (2010).

Wang, C. et al. Mmdental - a multimodal dataset of tooth cbct images with expert medical records. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28505276 (2025).

Agaku, I. T., Olutola, B. G., Adisa, A. O., Obadan, E. M. & Vardavas, C. I. Association between unmet dental needs and school absenteeism because of illness or injury among u.s. school children and adolescents aged 6-17years, 2011-2012. Preventive Medicine 72, 83–88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.037 (2015).

Sun, B., Wu, Z., Hu, Y. & Li, T. Golden subject is everyone: A subject transfer neural network for motor imagery-based brain computer interfaces. Neural Networks 151, 111–120 (2022).

Outland, B., Newman, M. M. & William, M. J. Health policy basics: Implementation of the international classification of disease, 10th revision. Annals of Internal Medicine 163, 554–556, https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-1933 (2015).

Kassebaum, N. J. et al. Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression. Journal of dental research 94, 650–658 (2015).

Eke, P. I., Dye, B., Wei, L., Thornton-Evans, G. & Genco, R. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the united states: 2009 and 2010. Journal of dental research 91, 914–920 (2012).

Hosntalab, M., Aghaeizadeh Zoroofi, R., Abbaspour Tehrani-Fard, A. & Shirani, G. Segmentation of teeth in ct volumetric dataset by panoramic projection and variational level set. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery 3, 257–265 (2008).

Wang, C.-W. et al. A benchmark for comparison of dental radiography analysis algorithms. Medical image analysis 31, 63–76 (2016).

Silva, G., Oliveira, L. & Pithon, M. Automatic segmenting teeth in x-ray images: Trends, a novel data set, benchmarking and future perspectives. Expert Systems with Applications 107, 15–31 (2018).

Abdi, A. H., Kasaei, S. & Mehdizadeh, M. Automatic segmentation of mandible in panoramic x-ray. Journal of Medical Imaging 2, 044003–044003 (2015).

A, P. teeth dataset. https://www.kaggle.com/pushkar34/teeth-dataset (2020).

Román, J. C. M. et al. Panoramic dental radiography image enhancement using multiscale mathematical morphology. Sensors 21, 3110 (2021).

Cui, W. et al. Ctooth: a fully annotated 3d dataset and benchmark for tooth volume segmentation on cone beam computed tomography images. In International Conference on Intelligent Robotics and Applications, 191–200 (Springer, 2022).

Panetta, K., Rajendran, R., Ramesh, A., Rao, S. P. & Agaian, S. Tufts dental database: a multimodal panoramic x-ray dataset for benchmarking diagnostic systems. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics 26, 1650–1659 (2021).

Liu, J., Hao, J. et al. Deep learning-enabled 3D multimodal fusion of cone-beam CT and intraoral mesh scans for clinically applicable tooth-bone reconstruction. Patterns 4 9 (2023).

Liu, W., Huang, Y. & Tang, S. A multimodal dental dataset facilitating machine learning research and clinic services https://doi.org/10.13026/s5z3-2766 (2023).

Goldberger, A. L. et al. Physiobank, physiotoolkit, and physionet: components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. circulation 101, e215–e220 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62206242).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chengkai Wang wrote this paper, and was in charge of creating this dataset. Yifan Zhang, Xingliang Huang and Liuxi Wu were with the hospital, responsible for providing patient data and offering technical consultancy in data. Chengyu Wu did the visualization of this data and provided overall suggestions for paper revision and writing. Yitong Wang did part of the data format conversion. Yiting Lu provided important guidance for the paper. Xiang Feng provided help on data conversion. Yaqi Wang was the principal investigator of this project, in addition also responsible for collecting the data as well as proofreading and revising the final version of this paper. Yaqi Wang supervised all aspects of the process.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Te authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Zhang, Y., Wu, C. et al. MMDental - A multimodal dataset of tooth CBCT images with expert medical records. Sci Data 12, 1172 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05398-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05398-7