Abstract

The research assesses soil salinity in the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh, collecting a total of 162 topsoil samples between March 1 and March 9, 2024, and processing them following the standard operating procedure for soil electrical conductivity (soil/water, 1:5). Electrical conductivity (EC) measurements obtained using a HI-6321 advanced conductivity benchtop meter were visualized spatially using bubble density mapping. The map demonstrates that soil salinity in the region of interest ranges from 0.05 to 9.09 mS/cm. This dataset provides a critical resource for soil salinity-related research in the region, offering valuable insights to support decision-makers in understanding and mitigating the impacts of soil salinity in Bangladesh’s coastal areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Soil salinization, the accumulation of mineral salts in soil and water, arises from natural hydrologic processes and human activity1. While natural events—such as floods and storm surges—contribute to salinization, the primary drivers are often human-induced factors, including the overuse of fertilizers, inadequate drainage, poor irrigation practices, and unsustainable agricultural management2. Globally, soil salinity poses a growing threat, affecting approximately one billion hectares of land, including 33 percent of irrigated agricultural fields and 20 percent of the world’s cultivated lands3. This challenge is especially critical as global agricultural output must continue to meet the food demands of a rapidly increasing population.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), salinity now affects 424 million hectares of topsoil (0–30 cm) and 833 million hectares of subsoil (30–100 cm)—equivalent to about 3 percent of global topsoil and 6 percent of subsoil4. The economic implications are substantial: salinization results in an annual global loss of approximately USD 27 billion due to land degradation, reduced crop yields, and the abandonment of once-fertile fields. Alarmingly, the spread of salinity is accelerating, with up to two million hectares of land affected annually5. Key drivers include insufficient precipitation, high surface evaporation in arid and semi-arid regions, saline water irrigation, and inadequate agricultural practices6.

Projections indicate that by 2050, over 50 percent of the world’s arable land could be impacted by salinization if current trends continue7. This rapid expansion stems from poor land management and climate change, which intensifies droughts, alters rainfall patterns, and contributes to rising sea levels—particularly affecting coastal areas. These factors amplify the salinization threat, making it a pressing global environmental and agricultural issue.

Bangladesh, among the most vulnerable nations to climate change and environmental degradation8, is facing a critical challenge with soil salinization, particularly in its coastal regions9. Situated in the low-lying Bengal Delta, Bangladesh is especially susceptible to rainfall10,11, flooding12, and saltwater intrusion, which exacerbate the salinity issue13. Notably, over 20 percent of Bangladesh’s total land area and more than 30 percent of its arable land lie along its coastline, making salinization a significant threat to national food security and economic stability9.

Over the past few decades, soil salinity in coastal Bangladesh has steadily worsened. Between 1973 and 20099, the area impacted by soil salinity grew by 26.7 percent—from 833,450 hectares to 1,056,190 hectares14. Projections suggest that this expansion will persist, with an anticipated annual increase of 146 square kilometers of salt-affected land5. Key drivers of this trend include reduced freshwater flows from upstream rivers, unpredictable rainfall, tidal amplification, storm surges, and insufficiently managed coastal polder systems15. These factors make salinity one of Bangladesh’s most pressing environmental concerns, severely affecting agriculture, water resources, and public health16. Given the reliance of Bangladesh’s coastal regions on rice production, shrimp farming, and other agricultural activities, the socio-economic impacts of salinization are substantial.

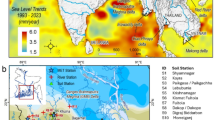

Coastal Bangladesh, a region home to millions and integral to the nation’s economy, faces heightened vulnerability to salinity-related impacts. Climate change has accelerated global sea level rise, significantly contributing to saltwater intrusion in these areas. From 1901 to 2018, global sea levels rose by 15–25 cm, with an average increase of 2.3 mm per year since 1970. This rate nearly doubled to 4.62 mm per year between 2013 and 202217. In Bangladesh, sea levels have risen at an average rate of 5 mm annually over the past three decades18, intensifying the risk to coastal ecosystems and communities.

Saltwater intrusion into coastal freshwater systems—surface water and groundwater—severely diminishes agricultural productivity. Salinization within crop root zones reduces soil fertility, inhibits plant growth, and ultimately lowers crop yields19,20. This intrusion also contaminates drinking water sources, putting public health at risk21. As coastal populations rely on these water sources for drinking and irrigation, they face increased health risks from high salt intake, including hypertension and cardiovascular diseases22.

The ramifications of salinity extend to infrastructure, leading to ground subsidence and disrupting local ecosystems vital to fisheries and other economic activities23. Thus, the salinization of coastal areas in Bangladesh jeopardizes not only agriculture but also the fishing, trade, and tourism sectors, with significant impacts on food security, water availability, and the overall quality of life. Projections indicate that by 2100, sea level rise could result in flooding of 12.34 percent to 18 percent of coastal zones, further intensifying salinization and displacing millions21.

The southwestern region of Bangladesh, home to the Sundarbans—the world’s largest mangrove forest—is particularly vulnerable to soil salinization. This area frequently experiences tropical cyclones, which bring storm surges that inundate vast areas with saline water. Between 1877 and 1995, Bangladesh experienced 154 cyclones, many of which led to storm surges24. Over ten tropical cyclones have struck the country in recent years alone, impacting approximately 3.45 million people25. These surges introduce high salt levels into agricultural lands, often rendering them unproductive for years. Unlike gradual salinization from sea-level rise, episodic salinization caused by cyclones can make the soil unsuitable for cultivation for up to a decade, severely affecting local food production.

Currently, soil salinity affects about 1.056 million hectares—nearly two-thirds of Bangladesh’s coastal area14. The southwest faces pronounced difficulty, where over-extraction of groundwater for irrigation has caused groundwater levels to drop, allowing seawater to seep into coastal aquifers26. This infiltration has led to the long-term contamination of surface water and groundwater with salt, exacerbating the region’s salinity challenges. Contributing factors include reduced freshwater inflows due to upstream dams, brackish-water prawn farming, and inadequate management of sluice gates and polders15.

With climate change driving rising sea levels and intensifying cyclones, more than 20 million people in southwestern Bangladesh face increasing risks from excessive salt intake through food and water sources22. The compounded effects of salinity on agriculture, water security, and public health make this region one of the most vulnerable in the world. As climate change accelerates salinization and amplifies environmental challenges, the long-term viability of farming, fishing, and other livelihoods is increasingly at risk. Consequently, research on salinity impacts has gained significant attention in Bangladesh.

Research on soil salinity in Bangladesh’s coastal areas is expanding as various methods and approaches aim to address this pressing issue. For instance, studies like those by Sarkar et al.14 have employed partial least squares regression to analyze soil salinity. In contrast, Sarkar et al.16 utilized machine learning techniques combined with satellite-based indices for improved detection accuracy. Other approaches have focused on remote sensing and spatial analyses, such as Morshed et al., who used satellite imagery to detect salinity levels across the region1. Meanwhile, Rezoyana et al. examined the impacts of salinity on coastal environments27, with Morshed et al. applying salinity-based zoning to guide land-use decisions5. Studies by Kumar et al.28 further highlighted relationships between soil salinity and other soil properties, adding valuable insights into salinity dynamics.

In specific regions like Khulna, local research has provided crucial salinity profiles, such as the work by Shaibur et al., who conducted an in-depth analysis of soil salinity gradients29. Fahim et al. explored how climate change influences salinity intrusion in coastal Bangladesh30. Other studies have examined broader impacts, including Hossain et al. and Rezoyana et al., who discussed salinity’s effect on local livelihoods27,31. In the southwestern coastal region, Ashrafuzzaman et al.32 reviewed long-term trends of salinity intrusion. Additionally, researchers like Haldar et al. have investigated coping mechanisms for rice farming under saline conditions22. At the same time, Bhuyan et al. studied the spatio-temporal variability of soil and water salinity across the south-central coast26. Akter et al.’s work on the hydrobiology of saline agricultural ecosystems33 underscores the environmental dimension of soil salinity.

However, field-based soil salinity measurements remain crucial for accurately assessing salinization’s spatial extent and intensity, particularly in climate-vulnerable regions like the southwest coast. Field data on salinity provide vital, localized insights that satellite observations alone cannot capture, supporting effective adaptation measures in agriculture and ecosystem management. Data published by organizations like the Soil Resource Development Institute (SRDI)34, the Department of Environment (DOE)35, the Water Resources Planning Organization (WARPO), and the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB)36 play an essential role in establishing adaptive strategies. However, gaps persist; for example, SRDI’s latest coastal region-based dataset is 14 years old37, and few studies provide comprehensive, spatially dense data across both topsoil and river water in the southwest coastal belt.

Field-based soil salinity measurements across the southwest coastal region are crucial, particularly under climate change. Ongoing measurements help monitor and manage the impacts of rising sea levels and the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events, both factors exacerbating soil salinity through saltwater intrusion and storm tides. By understanding salinity patterns in this region, researchers and policymakers can develop adaptive strategies to mitigate the detrimental effects on agricultural systems and local ecosystems. Accurate salinity data are essential for promoting sustainable land management practices and maintaining soil health and agricultural productivity in changing climate conditions.

Furthermore, these measurements are vital for informing climate-adaptive policies and regional planning and supporting sustainable development and environmental protection efforts in Bangladesh’s coastal areas. Several organizations play a crucial role in publishing salinity data from field-based measurements, including the Soil Resource Development Institute (SRDI)34, the Department of Environment (DOE)35, the Water Resources Planning Organization (WARPO), and the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB)36.

However, there are notable gaps in the available data. For example, although SRDI has published recent salinity data across the country, there has been insufficient focus on the specific conditions of the coastal regions38. Additionally, the dataset lacks detail on how salinity characteristics vary across the southern coastal belt. The last coastal region-based dataset was published over 14 years ago by SRDI37. Data published by the DOE34 and BWDB36 primarily focus on salinity levels in major rivers and lakes without considering topsoil salinity or regional-level variations. Field-based soil salinity measurements across the southwest coastal region have been infrequently studied and have sparse spatial sampling. To our knowledge, no comprehensive regional-level analysis that densely samples river water and topsoil is publicly available. Furthermore, advanced modeling and geospatial analyses of salinity patterns, incorporating field survey data, have not received adequate attention.

This study addresses these gaps by conducting a comprehensive soil sampling campaign at unprecedented density across three districts—Satkhira, Khulna, and Jessore—and analyzing the samples in the laboratory. We collected the data under specific soil conditions and land use (open fields, fallow land, and dry soil). The resulting dataset offers a crucial resource for soil salinity research in the area, providing valuable insights for decision-makers in Bangladesh’s coastal regions to better understand and address the ongoing and future impacts of soil salinity. It is also the first step in our work to establish a persistent community-driven co-active soil observatory39,40, where measurements train, calibrate and refine soil salinity models, whose predictions and predicted uncertainties then target subsequent measurements for efficacy and informativeness41.

Methods

Sample collection from field

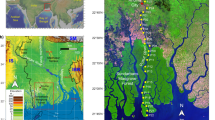

We collected soil data from three southwest coastal districts of Bangladesh, namely Khulna, Satkhira, and Jessore, excluding the Sundarbans (Fig. 1(a)). Our field data collection team comprised faculty, scientists, students, and professionals from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Khulna University of Engineering and Technology (KUET), and BRAC. The team was divided into five groups to conduct the soil-salinity data-collection campaign from March 1–9, 2024, in the study area. Before the campaign, we reviewed previous research papers, maps, documents produced by government authorities, and satellite images as foundational materials. Based on reconnaissance surveys, we developed five tentative routes connecting major union centers (Fig. 1(b)). The survey teams visited each major union center to identify suitable locations for collecting soil samples. One hundred sixty-two soil samples were collected along these routes and near the major centers (Fig. 1(b)). Additionally, we utilized river transport to collect samples from the riverbanks to the centers of the polders.

Our objective was to integrate soil salinity data with remote sensing data. Selecting an optimal location under the open sky required careful consideration to ensure accurate readings. We prioritized areas free from obstructions, such as trees and buildings, ideally situated alongside dry, open, and fallow fields (Fig. 2). After identifying a suitable site, we utilized Google My Maps to obtain coordinates and captured a geocoded photograph to accurately mark the location (Fig. 3(d)). At each selected site, we meticulously gathered 5 to 10 soil samples from an approximately 30 m × 30 m area. To collect the samples, we first cleared any surface disturbances and then excavated the soil to a depth of 30 cm (Fig. 3(a)). Each sample was carefully placed in a sample bag (Fig. 3(c)), ensuring proper geocoding within the bag (Fig. 3(d)). Subsequently, we mixed each collected sample to create a homogenized composite that accurately represented a particular location. Extensive photographic documentation captures various angles of the site and the collection procedure. After completing the sampling at one site, the team proceeded to the following designated location, repeating the meticulous process to ensure comprehensive data collection.

Data processing in laboratory

We processed the samples at the ESSG-WECG laboratory at KUET according to the standard operating procedure for soil electrical conductivity (soil/water, 1:5) proposed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations42. The sample testing procedure began with signing in on the timesheet and donning gloves and lab attire. We meticulously followed each step: a single packet was selected and moved to a clean location on the testing table, ensuring isolation from other packets nearby (Fig. 4(a)). We mixed the soil within the packet thoroughly to eliminate clumps using shaking and, if necessary, a spatula. We spread a portion of the well-mixed soil delicately onto a clean foil plate. We resealed the working packet, and the foil plate was placed in the oven for five to ten minutes to reduce moisture content (Fig. 4(b)). Larger particles were sieved out using a 1.0 mm mesh (Fig. 4(c)), and the filtered soil was mixed with deionized water in a clean beaker at a ratio of 1:5 (Fig. 4(d)). After stirring the mixture for 10 minutes (Fig. 4(e)), it was allowed to rest for 30 minutes (Fig. 4(f,g)). The conductivity was measured using a HI-6321 advanced conductivity benchtop meter (Fig. 4(h,i)). We recorded readings alongside the sample number and electrical conductivity (EC) (Fig. 4(j)) and took photographs of the instrument reading and test setup. After each sample analysis, we cleaned the equipment thoroughly and sanitized the workbench, ensuring an organized workspace for subsequent tests (Fig. 4(k)).

(a) Collecting soil from sample bag; (b) drying the soil in oven; (c) sieving the soil; (d) weighing the soil; (e) stirring the mixture; (f) placing the mixture to rest; (g) settling down of the mixture; (h) testing the mixture; (i) taking photograph of data; (j) storing the data; (k) cleaning the equipment.

Data Records

The processes—which included selecting sample sites, collecting data, calibrating sensors, analyzing data in the lab, and archiving data—are complete. The geographical location of sample sites, and soil salinity values (EC in mS/cm, constitute the metadata. This dataset contains the soil salinity data for 162 sample sites gathered between March 1 and 9, 2024. This article’s soil salinity dataset for Bangladesh’s southwest coastal regions is available at this link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14560019 and the dataset is in the XLSX format43.

Technical Validation

We validate our data by comparing it to existing literature (Table 1). In Fig. 5, bubble density maps show the distribution of soil salinity (EC in mS/cm) in the research area using specified ranges and classes (from 0.05 mS/cm to 9.09 mS/cm in five classes). Our study’s soil salinity distribution corresponds closely with prior studies’ findings, both in values and variability between different sections.

Code availability

No custom code was used in this study.

References

Morshed, M. M., Islam, M. T. & Jamil, R. Soil salinity detection from satellite image analysis: an integrated approach of salinity indices and field data. Environ. monitoring assessment 188, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-015-5045-x (2016).

Wu, J., Vincent, B., Yang, J., Bouarfa, S. & Vidal, A. Remote sensing monitoring of changes in soil salinity: a case study in inner mongolia, china. Sensors 8, 7035–7049, https://doi.org/10.3390/s8117035 (2008).

Negacz, K., Malek, Ž., de Vos, A. & Vellinga, P. Saline soils worldwide: Identifying the most promising areas for saline agriculture. J. arid environments 203, 104775, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2022.104775 (2022).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Global map of salt-affected soils (2024).

Morshed, M. M., Sarkar, S. K., Zzaman, M. R. U. & Islam, M. M. Application of remote sensing for salinity based coastal land use zoning in bangladesh. Spatial Inf. Res. 29, 353–364, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41324-020-00357-3 (2021).

Nachshon, U. Cropland soil salinization and associated hydrology: Trends, processes and examples. Water 10, 1030, https://doi.org/10.3390/w10081030 (2018).

Butcher, K., Wick, A. F., DeSutter, T., Chatterjee, A. & Harmon, J. Soil salinity: A threat to global food security. Agron. J. 108, 2189–2200, https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2016.06.0368 (2016).

Sarkar, S. K., Rahman, M. A., Esraz-Ul-Zannat, M. & Islam, M. F. Simulation-based modeling of urban waterlogging in khulna city. J. Water Clim. Chang. 12, 566–579, https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2020.256 (2021).

Hasan, M., Rahman, M., Haque, A. & Hossain, T. Soil salinity hazard assessment in bangladesh coastal zone. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Disaster Risk Management, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 12–14 (2019).

Saha, A. & Ravela, S. Rapid statistical-physical adversarial downscaling reveals bangladesh’s rising rainfall risk in a warming climate. arXiv 2408.11790 (2024).

Saha, A. & Ravela, S. Rapid climate model downscaling to assess risk of extreme rainfall in bangladesh in a warming climate. arXiv 2412.16407 (2024).

Qiu, J., Ravela, S. & Emanuel, K. Bangladesh’s accelerating coastal flood hazard. arXiv 2312.06051 (2023).

Rudra, R. R. & Sarkar, S. K. Artificial neural network for flood susceptibility mapping in bangladesh. Heliyon 9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16459 (2023).

Sarkar, S. K., Rudra, R. R., Nur, M. S. & Das, P. C. Partial least-squares regression for soil salinity mapping in bangladesh. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110825, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110825 (2023).

Akash, S. H. et al. Assessment of coastal vulnerability using integrated fuzzy analytical hierarchy process and geospatial technology for effective coastal management. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 53749–53766, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-28317-y (2024).

Sarkar, S. K. et al. Coupling of machine learning and remote sensing for soil salinity mapping in coastal area of bangladesh. Sci. Reports 13, 17056, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44132-4 (2023).

Fatoric, S. & Chelleri, L. Vulnerability to the effects of climate change and adaptation: The case of the spanish ebro delta. Ocean. & Coast. Manag. 60, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.12.015 (2012).

Uzzaman, M. A. Impact of sea level rise in the coastal areas of bangladesh: A macroeconomic analysis. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 5, 105–109 (2014).

Zörb, C., Geilfus, C.-M. & Dietz, K.-J. Salinity and crop yield. Plant biology 21, 31–38, https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.12884 (2019).

Umamaheswari, L., Hattab, K. O., Nasurudeen, P. & Selvaraj, P. Should shrimp farmers pay paddy farmers?: the challenges of examining salinisation externalities in south india. SANDEE working paper/South Asian Netw. for Dev. Environ. Econ. no. 41-09 (2009).

Wongsirikajorn, M., McNally, C. G., Gold, A. J. & Uchida, E. High salinity in drinking water creating pathways towards chronic poverty: A case study of coastal communities in tanzania. Ambio 52, 1661–1675, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-023-01879-4 (2023).

Haldar, P., Saha, S., Ahmed, M. & Islam, S. Coping strategy for rice farming in aila affected south-west region of bangladesh. J. Sci. Technol. Environ. Informatics 4, 313–326, https://doi.org/10.18801/jstei.040217.34 (2017).

Sahbeni, G., Ngabire, M., Musyimi, P. K. & Székely, B. Challenges and opportunities in remote sensing for soil salinization mapping and monitoring: A review. Remote. Sens. 15, 2540, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15102540 (2023).

Dasgupta, S., Hossain, M. M., Huq, M. & Wheeler, D. Climate change and soil salinity: The case of coastal bangladesh. Ambio 44, 815–826, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-015-0681-5 (2015).

Sarkar, S. K., Rudra, R. R. & Santo, M. M. H. Cyclone vulnerability assessment in the coastal districts of bangladesh. Heliyon 10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23555 (2024).

Bhuyan, M. I., Mia, S., Supit, I. & Ludwig, F. Spatio-temporal variability in soil and water salinity in the south-central coast of bangladesh. Catena 222, 106786, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106786 (2023).

Rezoyana, U., Tusar, M. K. & Islam, M. A. Impact of salinity: A case study in saline affected satkhira district. Open J. Soc. Sci. 11, 288–305, https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2023.115020 (2023).

Kumar, U., Mitra, J. & Mia, M. Seasonal study on soil salinity and its relation to other properties at satkhira district in bangladesh. Progressive Agric. 30, 157–164 (2019).

Shaibur, M. R. et al. Gradients of salinity in water sources of batiaghata, dacope and koyra upazila of coastal khulna district, bangladesh. Environ. Challenges 4, 100152, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100152 (2021).

Fahim, T. C. & Arefin, S. Climate change-induced salinity intrusion and livelihood nexus: A study in southwest satkhira district of bangladesh. Int. J. Rural. Manag. 20, 106–123, https://doi.org/10.1177/09730052231176915 (2024).

Hossain, M. Z. et al. Impact of soil salinity on livelihood strategies: A study on two selected villages of satkhira district. Khulna Univ. Stud. 43–48 (2010).

Ashrafuzzaman, M., Artemi, C., Santos, F. D. & Schmidt, L. Current and future salinity intrusion in the south-western coastal region of bangladesh. Span. J. Soil Sci. 12, 10017, https://doi.org/10.3389/sjss.2022.10017 (2022).

Akter, R. et al. Hydrobiology of saline agriculture ecosystem: A review of scenario change in south-west region of bangladesh. Hydrobiology 2, 162–180, https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrobiology2010011 (2023).

Soil Resource Development Institute. Annual report 2018-2019 (2019).

Department of Environment. Surface and ground water quality report. Tech. Rep., National Resource Management Research Wing, Department of Environment, Bangladesh (2023).

Board, B. W. D. Long term monitoring of climate change impacts on the coastal areas of bangladesh. Accessed: 2024-10-20 (2022).

Soil Resources Development Institute. Soil salinity report. Accessed: 2024-10-20 (2010).

Soil Resource Development Institute. Annual report 2022. Accessed: 2024-10-20 (2022).

Ravela, S. Tractable non-gaussian representations in dynamic data driven coherent fluid mapping. Handb. Dyn. Data Driven Appl. Syst. Vol. 1 29–46, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95504-9_2 (2018).

Ravela, S., Blasch, E. P. & Darema, F. Dynamic data-driven applications systems and information-inference couplings. Handb. Dyn. Data Driven Appl. Syst. Vol. 2 55–70, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27986-7_2 (2023).

Trautner, M., Margolis, G. & Ravela, S. Informative neural ensemble kalman learning. arXiv 2008.09915 (2020).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Standard operating procedure for soil electrical conductivity soil/water, 1:5. Accessed: 20-02-2024 (2021).

Sarkar, S. K. et al. A Root-Zone Soil Salinity Observatory for Coastal Southwest Bangladesh. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14560019 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the MIT Climate Grand Challenge Jameel Observatory CREWSNet and Weather and Climate Extremes projects. Schmidt Sciences, LLC and Liberty Mutual (029024-00020) also supported this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Showmitra Kumar Sarkar: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Collection, Data Curation, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review and Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Resources, Investigation; Mafrid Haydar: Data Collection, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing – Review and Editing; Rhyme Rubayet Rudra: Data Collection, Writing – Review and Editing; Tanmoy Mazumder: Data Collection, Writing – Review and Editing; Md. Sadmin Nur: Data Collection, Writing – Review and Editing; Md. Shahriar Islam: Data Collection, Writing – Review and Editing; Shakib Mohammad Sany: Data Collection, Writing – Review and Editing; Tanzim Al Noor: Data Collection, Writing – Review and Editing; Shakil Ahmed: Data Collection, Writing – Review and Editing; Myisha Ahmad: Data Collection, Writing – Review and Editing; Annajmus Sakib: Data Collection, Writing – Review and Editing; Sai Ravela: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Collection, Data Curation, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review and Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition, Resources, Investigation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarkar, S., Haydar, M., Rudra, R.R. et al. A Topsoil Salinity Observatory for Arable Lands in Coastal Southwest Bangladesh. Sci Data 12, 1204 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05447-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05447-1