Abstract

The Agroforestry Species Switchboard is a comprehensive vascular plant database that guides users to information for a particular taxon from a global but fragmented set of resources. Via standardized species names, a user can rapidly determine which among the 59 contributing databases contain information for a species of interest, and understand how this information can be accessed. By providing taxonomic identifiers to World Flora Online, it is straightforward to check for changes in taxonomy. Among the 59 databases referenced, ten covered over 10,000 species, 20 between 1,000 and 10,000 species, and 22 between 100 and 1,000 species. The top ten plant families for species richness across covered databases were the Fabaceae (9,537 species), Asteraceae (6,041), Rubiaceae (4,812), Poaceae (3,947), Myrtaceae (3,544), Euphorbiaceae (2,689), Malvaceae (2,478), Rosaceae (2,374), Lauraceae (2,334) and Lamiaceae (2,107). Information included in the Switchboard distinguishes 54,812 tree-like species, covering most known tree species globally. Among its applications, the Switchboard can assist species selection for ecological restoration projects to synergize biodiversity and human well-being objectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The Earth’s life support systems depend on biodiversity to an extent that requires nature conservation far beyond protected areas1,2,3,4. Ecological restoration seeks to recover biodiversity and ecosystem integrity, while delivering ecosystem services and ensuring human well-being5,6,7,8,9. Nature-based solutions implemented in human-modified landscapes are increasingly critical for social-ecological resilience10,11. Yet taxon-specific knowledge that can inform restoration and diversification planning remains highly fragmented among dozens of ‘siloed’ databases, each with substantial gaps, contributing to the dominant use of a narrow set of intensely researched and promoted species in agriculture12, forestry13 and sometimes even ecological restoration14,15.

The Agroforestry Species Switchboard (hereinafter: the Switchboard) was specifically developed to facilitate access to detailed – yet fragmented – information for a broad range of tree species to support their wider use. The adoption of the term “Switchboard” is because of the role of the database as a central hub to guide users to a wide range of particular information sources. Its principal focus is on international databases that document tree species, supplemented with different types of database covering botanical, biochemical, biophysical, physiological, ecological, biogeographic, conservation, agronomic, silvicultural, nutritional, socioeconomic and cultural characteristics for plant taxa of all growth forms. Including 107,269 accepted plant names, the Switchboard in its current version spans over a quarter of accepted plant species globally and covers 59 scientific- and practitioner-oriented databases.

The Switchboard can be used by practitioners, researchers and policy makers to readily access descriptions of vascular plant species, including information on products and services provided, details on risks of invasiveness, and descriptions such as wood density and food nutritional compositions. Referencing of a species through the Switchboard to the included specialized databases such as on timber, forage and food uses can aid in prioritizing species for these functions, while information obtained through databases linked to the Switchboard related to species’ environmental ranges can further support species-site-use matching.

As linking through the Switchboard is done via a standardized plant name, users do not need to comb and check each individual reference database for potential synonyms or orthographic (spelling) variations in botanical names. An additional benefit, based on listing the original names of taxa used by databases, is that practitioners that are not familiar with recent taxonomic revisions can recover information for taxa by their synonyms. With the Switchboard having standardized the great majority of taxa to the taxonomic backbone of World Flora Online16 (WFO), via the taxonomic identification field (‘taxonID’) users can rapidly retrieve data from the WFO website (https://www.worldfloraonline.org/), including information on taxonomic revisions, from particular flora, from the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (https://www.iucnredlist.org/), and on geographic distribution derived via the Plants of the World Online (https://powo.science.kew.org/).

Developers of new decision-support tools can improve the utility of their resources by linking to numerous other databases using the Switchboard as an intermediary. Recent published examples of such an application are the GlobalUsefulNativeTrees7 (GlobUNT) and EcoregionsTreeFinder17 databases, which respectively provide lists of native tree species for a selected country or ecoregion. Filtered species lists from these databases link directly to entries in the Switchboard, which allows further narrowing down and the corroboration of species selections.

Methods

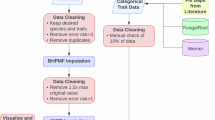

Data collation

Here we document the collation of information for the Agroforestry Species Switchboard. Initial development of the Switchboard began in 2013 and it has now evolved to the present Version 4.0, which has reached a stage where its functionality merits wider adoption and promotion. The first criterion to link a database through the Switchboard is that it contains information about tree species, since diversifying tree use in restoration and broader tree planting initiatives is a primary concern for the authors and the institutes where they work. However, databases to be linked do not need to exclusively relate to trees and, where available, links to data on other vascular plant forms within the constituent databases are included in the Switchboard. The second criterion to reference a database is that normally the information it contains should have international, where possible global, coverage. However, databases focusing on larger nations that include different ‘botanical countries’ (level 3 areas in the World Geographical Scheme for Recording Plant Distributions18), such as the USA (e.g., USDA-Plants19) and Australia (e.g., EUCLID20), are included when these document sufficient numbers of species also known to be grown in wider locations globally. Third, to be linked it should be possible to retrieve taxon-specific information easily from the database, in order to allow cross-correspondence via species names. Fourth, along with databases per se, a smaller number of books, scientific articles or spreadsheet documents were chosen to be linked to the Switchboard when they contained useful information that can easily be cross-linked within a database environment. Fifth and finally, to be linked the databases should generally be available at no cost to the user, although in certain important cases exceptions were made. Supporting information presented in the Zenodo archive in the Switchboard contributing databases.xlsx file (hereinafter: metadata) indicates how and when reference database links were integrated into the Switchboard, and provides further information on individual database properties. Future versions of the Switchboard will explore the integration of further databases.

Databases referenced within the Switchboard fall into four categories (Table 1, 2, metadata).

-

1.

ICRAF databases: these are databases that were (co-) developed by CIFOR-ICRAF. These consist of: the African Wood Density Database21 (AWDD, https://apps.worldagroforestry.org/treesnmarkets/wood); the Agroforestree Database22 (AFD, https://apps.worldagroforestry.org/treedb2/); the CIFOR-ICRAF Tree Genebank23 (ICRAF-gene, https://treegenebank.cifor-icraf.org/); GlobalUsefulNativeTrees7 (GlobUNT, https://worldagroforestry.org/output/globalusefulnativetrees); the Priority Food Tree and Crop Food Composition Database24 (ICRAF-nutri, https://apps.worldagroforestry.org/products/nutrition/index.php/home/); RELMA-ICRAF Useful Trees25 (RELMA-ICRAF, https://apps.worldagroforestry.org/usefultrees/index.php); TreeGOER: Tree Globally Observed Environmental Ranges26 (TreeGOER, https://zenodo.org/records/7922927); Useful Tree Species for Africa27 (UTSA, https://patspo.shinyapps.io/UsefulTreeSpecies4Africa/; https://www.worldagroforestry.org/output/useful-tree-species-africa); and the Vegetation map for Africa species distribution maps28 (V4A, https://vegetationmap4africa.org/).

-

2.

Invasive species databases: these are databases that document potentially invasive species29. Identifying invasive species – in order not to introduce them and to remove them if present – can be a key process in ecological restoration that is explicitly mentioned in ecosystem restoration principles8,9. For this reason, and also based on a conversation with the Deputy Executive Secretary at the Convention of Biological Diversity Secretariat on how to feature these species, these databases are listed in a separate category. These databases consist of: CABI Compendium Invasive Species30 (CABI-ISC, https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/product/QI); the Country Compendium of the Global Registry of Introduced and Invasive Species31 (GRIIS, https://zenodo.org/records/6348164); and the Global Invasive Species Database32 (GISD, https://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/).

-

3.

Spreadsheet databases: these are databases that typically can be downloaded as a single file, where the user can find information for a taxon of interest by searching for its name within the document. Some databases can be searched online, but we did not obtain taxon-specific links. Spreadsheet databases consist of: A global database of plant services for humankind33 (GPS, https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/PLANT_USES_PLANT_BOOK_xlsx/13625546/3); Árboles de Centroamérica: un Manual para Extensionistas34 (Spanish) (AdC, https://repositorio.catie.ac.cr/handle/11554/9730); BIOMASS: Estimating Aboveground Biomass and Its Uncertainty in Tropical Forests35 (BIOMASS, https://cran.r-project.org/package=BIOMASS); Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases36 (Duke-Ethno and Duke-Phyto, http://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/); eHALOPH: a database of halophytes and other salt-tolerant plants37 (eHALOPH, https://ehaloph.uc.pt/); Especies para la restauración en Mesoamérica38 (Spanish) (Restoracion, data obtained from http://www.especiesrestauracion-uicn.org/especies.php in 2016; species information available now via https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/ST-GFE-no.03.pdf); the Food Plants International database39 (FoodPlants, https://foodplantsinternational.com/plants/); GlobAllomeTree: Assessing volume, biomass and carbon stocks of trees and forests40 (GlobAllome; http://www.globallometree.org/); the Global Species Matrix41 (GSM, https://pfaf.org/user/CarbonFarmingSolution.html); the Tropical Forestry Handbook: Species Files in Tropical Forestry13 (TFH, http://www.springer.com/us/book/9783642546006); the Tallo database42 (Tallo, https://zenodo.org/records/6637599); The International Timber Trade: a working list of commercial timber tree species43 (ComTimber, https://www.bgci.org/resources/bgci-tools-and-resources/a-working-list-of-commercial-timber-tree-species/); the World Checklist of Useful Plant Species44 (WCUPS, https://knb.ecoinformatics.org/view/doi:10.5063/F1CV4G34); and the World list of plants with extrafloral nectaries45 (Extrafloral, http://www.extrafloralnectaries.org/).

-

4.

Other databases: these are databases not listed in the previous categories. For these databases, the Switchboard includes taxon-specific links. These databases consist of: the African Orphan Crops Consortium priority crops46 (AOCC, https://africanorphancrops.org/meet-the-crops/); Australian Tropical Rainforest Plants47 (LUCID-rain, https://apps.lucidcentral.org/rainforest/text/intro/index.html); CABI Compendium Forestry48 (CABI-Forest, https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/product/QF); the CABI Compendium49 (CABI, https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/journal/cabicompendium); ECHOcommunity Plant Search50 (ECHO, https://www.echocommunity.org/en/search/plants?q=*); the ECOCROP Database of Crop Constraints and Characteristics51 (ECOCROP, https://gaez.fao.org/pages/ecocrop); EUCLID Eucalypts of Australia20 (LUCID-euc, https://apps.lucidcentral.org/euclid/text/intro/index.html); European Forest Genetic Resources Programme Species52 (EUFORGEN, https://www.euforgen.org/species); FamineFoods53 (FamineFoods, https://www.purdue.edu/hla/sites/famine-foods/); Feedipedia54 (Feedipedia, https://feedipedia.org); the INBAR Bamboo and Rattan Species Selection tool55 (INBAR, https://speciestool.inbar.int/); ITTO Lesser Used Species56 (TropTimber, http://www.tropicaltimber.info/); Mansfeld’s World Database of Agriculture and Horticultural Crops57 (Mansfeld, https://mansfeld.ipk-gatersleben.de); the New World Fruits Database58 (NWFD, http://nwfdb.bioversityinternational.org/); NewCROP59 (NewCROP, https://hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/Indices/index_ab.html); Optimizing Pesticidal Plants60 (OPTIONs, https://options.nri.org/); Oxford Plants 40061 (Oxford400, https://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/bol/plants400); Plant Resources of South-East Asia62 (PROSEA, https://prosea.prota4u.org/); Plant Resources of Tropical Africa63 (PROTA, https://prota.prota4u.org/); the PLANTS Database19 (USDA-Plants, https://plants.sc.egov.usda.gov/); Plants For A Future41 (PFAF, https://pfaf.org/user/); Portal de Plantas Medicinais, Aromáticas e Condimentares64 (Portuguese, PPMAC, https://www.ppmac.org/medicinal-aromatica-condimentar); Seed Leaflets65 (Leaflets, https://sl.ku.dk/rapporter/); Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry66 (Pacific, https://agroforestry.org/free-publications/traditional-tree-profiles); The Gymnosperm Database67 (Gymnosperm, https://www.conifers.org/index.php); The Wood Database68 (TheWood, https://www.wood-database.com/); Tropical Forages69 (SoFT, https://www.tropicalforages.info/text/intro/index.html); tropiTree70 (TropiTree, https://ics.hutton.ac.uk/tropiTree/index.html); Useful Temperate Plants71 (UtempP, https://temperate.theferns.info/); Useful Tropical Plants72 (UtropP, https://tropical.theferns.info/); WATTLE Acacias of Australia73 (LUCID-wat, https://apps.lucidcentral.org/wattle/text/intro/index.html); and World Economic Plants in GRIN-Global74 (USDA-GRIN, https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxon/taxonomysearchwep).

Taxonomic standardization

Taxonomic standardization among referenced databases and the Switchboard was achieved in the R statistical environment75 (version 4.2.1) with functions WorldFlora::WFO.match.fuzzyjoin() and WorldFlora::WFO.one() from the WorldFlora package76 (version 1.14-5). For databases where information was downloaded on the naming authority (see metadata), this information was also utilized during matching via the ‘Authorship’ argument, similar as in workflows previously documented by Kindt77 and in the Zenodo archive by the Standardization-R-script.pdf file. Taxonomic names were matched first against the taxonomic backbone of WFO16 (version v.2023.12; https://www.worldfloraonline.org/downloadData). Direct matches retained in subsequent standardization steps were documented as ‘direct’ in the ‘Match.Type’ field; the Switchboard (file: Switchboard_4.txt) contains 318,268 entries of this match category. Suggested fuzzy matches accepted after visual inspection were documented as ‘manual’ in the ‘Match.Type’ field; the Switchboard contains 12,408 retained entries of this match category. Next, still unmatched names were compared with the taxonomic backbone of the World Checklist of Vascular Plants78 (WCVP; version 11; https://doi.org/10.34885/ccpn-9465). Where matches here were identified, these were assigned to ‘direct’ or ‘manual’ categories, referencing ‘WCVP’ in the ‘Backbone’ field; the Switchboard includes 202 and 97 such entries, respectively. A final step involved the matching of current names suggested for synonyms via WCVP with the WFO backbone. Where matches here were indicated, these were documented as ‘direct via WCVP’ or ‘manual via WCVP’ entries (93 and 47 records, respectively).

The taxonomic standardization described above was achieved by processing the contributing databases individually, except for two collectively processed groups of databases. The first of these groups (‘STATIC’ databases, see metadata) consisted of databases whose contents had not changed since the previous version of the Switchboard, or where we were unable to obtain a more current taxon-based data set. The second of these groups (‘ZENODO’ databases, see metadata) consisted of databases accessed from Zenodo archives. Both STATIC and ZENODO databases had previously been standardized based on protocols similar to those described above, although an older version of the WFO taxonomic backbone had been used. When processing the STATIC and ZENODO databases here, we first matched taxa via the WFO ‘taxonID’ field from the match with the older version of WFO with the ‘taxonID’ from the more recent version (v.2023.12) used in standardization workflows for Switchboard 4.0, provided that the older matches had been classified as ‘direct’. Still unmatched taxa for STATIC and ZENODO database groups were then processed further with the same WorldFlora workflows applied in the current study to individual databases.

Taxa not matched by the above approaches were removed from the Switchboard if taxonomic names cross-referenced to those for algae (screening names mainly against https://www.algaebase.org/), fungi (comparing names mainly against https://www.indexfungorum.org/names/names.asp), bacteria or animals (checking names through manual online comparisons in the last two cases). The metadata indicates for which of the 59 registered databases such organisms were encountered and provides examples. Also removed from the Switchboard were cultivar entries for plants in linked databases, such as Actinidia arguta ‘AADA’, and hybrids, where databases had listed these in a format such as Megathyrsus maximus × M. infestus.

Several taxa at infraspecific levels (var., subsp. and f.) could not be matched with these procedures. These infraspecific taxa were matched next with a previous species-level match. Where this was not possible as there was no previous entry at species-level, we conducted the standardization protocols at species level.

Following the above standardization steps, cases occurred where plants of the same taxon name had been matched to different records of the taxonomic backbone, typically as a consequence of different authorities being provided for taxa or authorities being given only in some databases. To deal with these situations – unless there was information on the authority from the database that suggested otherwise – in the case of trees, we generally chose to select the match based on naming authorities given in GlobalTreeSearch79 (GTS) version 1.8 which lists 57,681 species. (Note that GTS is not one of the databases linked to the current version of the Switchboard for copyright reasons; however, our approach for authority matching does facilitate cross-comparison). We adopted the same approach for entries not covered by GTS but harvested from USDA-GRIN74, which contained 13,088 vascular plants and also provided naming authorities. For practical reasons, standardizations made via GTS and USDA-GRIN were undertaken first for batches of databases (see metadata). Standardizations were then repeated after combining information from all databases.

After concluding these workflows, 1,109 unmatched taxa remained that were therefore not included in the Switchboard_4.txt file. The list of 1,169 unmatched records is available as a separate data file (see Switchboard_unmatched.txt).

Final checks to identify and correct situations where taxa had been matched differently are described in the section on technical validation below.

Taxonomic, geographic and phylogenetic coverage

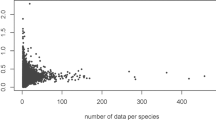

The Switchboard contains 619 families, 10,494 genera and 107,269 species of vascular plants (Tables 1, 2). Two databases stood out for their very high number of included species after standardization, TreeGOER and WCUPS, with 47,927 and 40,047 species, respectively. These were among ten databases in total that covered over 10,000 species. Another 20 databases covered between 1,000 and 10,000 species, and a further 22 between 100 and 1,000 species. Seven databases covered less than 100 species, but among these is included GPS which is a special case because it lists information exclusively at the genus level (it lists 4,370 genera).

We inferred the continental native distribution of species from information in the WCVP. The WCVP identification field (‘plant_name_id’) to obtain distribution on geographical distributions from the WCVP was inferred by linking the WFO and WCVP backbone databases via their ‘IPNI ID’ fields. This was possible for 96,957 species. Where matching of the IPNI ID field was not possible, matching by the WorldFlora package and the WCVP taxonomic backbone was undertaken, leading to entry of another 8,168 species. The matched WCVP identification (‘WCVP_ID’) is included in the species file of the Switchboard.

For four continents (Africa [AFR], tropical Asia [OAS], Southern America [SAM] and Australasia [AUS]), the two databases with very high numbers of species linked to the Switchboard overall (TreeGOER and WCUPS) ranked between them first and second among all linked databases for continental species richness (see Database coverage spreadsheet.xlsx file in the archive). For temperate Asia [EAS], WCUPS ranked highest and FoodPlants second; for northern America [NAM] USDA-Plants had the highest richness and WCUPS second. USDA-Plants ranked second for both the Pacific [PAC] and Europe [EUR], where TreeGOER and GRIIS ranked first, respectively. 54 of the linked databases contained species native to seven or eight (all) continents. EUR was the continent with the fewest databases covering it, although 48 databases still included some of its native species.

The top ten plant families for species richness across the Switchboard were (in descending order) the Fabaceae (9,537 species), Asteraceae (6,041), Rubiaceae (4,812), Poaceae (3,947), Myrtaceae (3,544), Euphorbiaceae (2,689), Malvaceae (2,478), Rosaceae (2,374), Lauraceae (2,334) and Lamiaceae (2,107) (see Families coverage spreadsheet.xlsx file in the archive). Collectively these represent 37.2% of all listed species on the Switchboard. Excluding the Myrtaceae from the top six for species richness, the same families were identified as among the top five for species richness in WCUPS alone (Diazgranados et al. 2020). The top five families for species richness also ranked highly when considering their richness compared to other families in their native continents. The overall top-ranking Fabaceae had the most species of any family for entries native to AFR, OAS, SAM and AUS, while this was the case for the overall second-ranking Asteraceae for SAM and EUR, for the overall third-ranking Rubiaceae for PAC and for the overall fourth-ranking Poaceae for EAS.

The cladogram of Fig. 1 summarizes the phylogenetic diversity of the Switchboard. The phylogenetic tree was constructed via the V.PhyloMaker2 R package80 (version 0.1.0) with the GBOTB.extended.TPL tree and “S3” scenarios. To represent each family, we selected the most frequently represented species for the family in the Switchboard and matched it with the same species, same genus or another species of the family among the GBOTB tips (the Families coverage spreadsheet.xlsx file documents the matched species and taxonomic level of matching to GBOTB). 177 families were excluded from the analysis as no matching GBOTB tip was found. The cladogram was constructed via the ggtree81 (version 3.6.2) and ggtreeExtra82 (version 1.8.1) packages with ggplot283 (version 3.5.1). The cladogram illustrates the wide taxonomic and geographic coverage of the Switchboard. The Switchboard includes 106 families that are native to all continents. The cladogram also shows extreme cases such as 63 families being native to a single continent. Including families without matching GBOTB tip and not shown in the cladogram for that reason, there were 67 such families in the Switchboard; among these, 50 (48 in the cladogram) consisted of a single genus and 29 (26 in the cladogram) of a single species.

Cladogram of 442 plant families documented in the Switchboard based on matching GBOTB tips for representative taxa. The circular heatmap shows the number of species native to Africa (1), tropical Asia (2), temperate Asia (3), southern America (4), northern America (5), Australasia (6), Pacific (7) and Europe (8) based on the WCVP. The bar graph shows the number of contributing databases to the Switchboard with information for each family.

Flagging of tree species

Not including the global species list from GTS in Switchboard version 4.0 (due to copyright restrictions) presented the opportunity for an alternative system of identifying species as tree or woody perennial species. We opted for a classification system for identifying species as tree-like that also potentially included taxa that had been deliberately excluded from GTS of cycads, tree ferns, tree-like Poaceae, Bromeliaceae, Musaceae and hybrid species79. For example, Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit no longer features in GTS as it was hypothesized that the species arose as a direct result of cultivation of one or both of its diploid parents (personal communication with Emily Beech, head of Conservation Prioritization, BGCI, 6th September 2024). GTS adopted the tree definition agreed by IUCN’s Global Tree Specialist Group: a woody plant with usually a single stem growing to a height of at least two metres, or if multi-stemmed, then at least one vertical stem five centimetres in diameter at breast height.

The species file of the Switchboard (file Switchboard_species.txt) provides the field of ‘Tree’ that flags and defines 54,812 tree species sensu the Switchboard. The file (‘Tree-like justification’ field) contains the justification for flagging a species as tree-like based on the consecutive processes below:

-

1.

Batch 1 flagged species included in TreeGOER (47,927 species), TreeGOER+84 (flagging 2,031 extra species), GlobUNT (1,004) or the species list from an article providing a synthesis of global tree biodiversity data85 (1,229, the same standardization pipeline was applied to the appendix of this article).

-

2.

Batch 2 flagged species not identified in batch 1 with the lifeform described in the WCVP of liana (1,576 species), tree (651), herbaceous tree (92), bamboo (25) or herbaceous bamboo (4).

-

3.

Batch 3 flagged 179 species present in Tallo42 (a database described as containing records of individual trees) and that were not flagged previously.

-

4.

Batch 4 flagged species present in databases expected only to include tree species given the scope of these databases: RELMA-ICRAF (43 species), AWDD (4 extra species), INBAR (4), ComTimber (2), AFD (1), EUFORGEN (1), Pacific (1), TheWood (1) and TropTimber (1).

-

5.

Batch 5 flagged species that had not been flagged earlier, where there was information in a database included in the Switchboard that aided their flagging as trees: UTropP (13 species), PROSEA (10 extra species), LUCID-rain (4), USDA-Plants (2) and UTempP (1).

-

6.

Batch 6 flagged five species that had not been flagged earlier, where there was information available in WFO of a tree-like description.

This flagging process in effect represents one application domain for the Switchboard, where information on presence of a species in a database allows specific analyses. Another direct application that is not comprehensively shown here is to rank and tentatively prioritize86 species by the number of databases where they occur. Following our classification of species as tree-like, the top 25 most identified species in the Switchboard in descending order by total listings are Tamarindus indica (listed by 40 databases), Samanea saman (39), Vachellia nilotica (39), Cocos nucifera (38), Mangifera indica (38), Albizia lebbeck (37), Ceiba pentandra (37), Anacardium occidentale (36), Neltuma juliflora (36), Olea europaea (36), Psidium guajava (36), Eucalyptus camaldulensis (35), Gliricidia sepium (35), Persea americana (35), Azadirachta indica (34), Faidherbia albida (34), Melia azedarach (34), Moringa oleifera (34), Senna siamea (34), Acacia auriculiformis (33), Cedrela odorata (33), Enterolobium cyclocarpum (33), Jatropha curcas (33), Leucaena leucocephala (33) and Morus alba (33).

Taxonomic, phylogenetic and geographic coverage of tree species

The top 10 families for species richness considering tree-like species only were (in descending order) the Fabaceae (5,061 species), Rubiaceae (3,954), Myrtaceae (3,353), Lauraceae (2,304), Euphorbiaceae (1,823), Malvaceae (1,692), Melastomataceae (1,552), Annonaceae (1,481), Arecaceae (1,332) and Sapotaceae (1,109) (see Families coverage spreadsheet.xlsx file). The same top 10 families and their rankings of richness for tree species were identified for GTS by Beech, et al.79. Considering the native continents of tree-like species, the first and second ranking families for richness for AFR, OAS, SAM, AUS and PAC were always among the top four families in terms of richness globally for all tree-like species. In the cases of EAS and EUR, however, the Rosaceae, which globally only ranked 12th in species richness (with 1,082 tree species) was the top-ranked family, with 417 and 176 species, respectively. In another illustration of divergent distributions, for NAM the Fagaceae was the second-ranked family for species richness (with 280 tree-like species) even though this family only ranked 16th globally (with 860 tree-like species). Interestingly, tree-like Poaceae and Musaceae species that are excluded from GTS79 ranked 23rd and 101st, respectively, in the Switchboard among families in terms of species richness (617 and 65 tree-like species, respectively). Bromeliaceae species that were excluded from GTS79, but that theoretically could have been flagged as tree species by the processes that we used, were also not included among trees sensu the Switchboard, whereas among all species this family ranked 110th (177 species, including Ananas comosus as the most frequently encountered across databases). The Switchboard also includes 24 tree-like Zamiaceae species,13 tree-like Cycadaceae species and 20 tree-like Cyatheaceae species, all of which were excluded by definitions for GTS79.

A cladogram for the 285 families with tree-like species representatives in the Switchboard, calculated according to the methods applied above (Fig. 1), is present in Fig. 2.

Cladogram of all 285 plant families containing tree-like species documented in the Switchboard based on matching GBOTB tips for representative taxa. The circular heatmap shows the number of species native to Africa (1), tropical Asia (2), temperate Asia (3), southern America (4), northern America (5), Australasia (6), Pacific (7) and Europe (8) based on the WCVP. The bar graph shows the number of contributing databases to the Switchboard with information for each family.

We also constructed a dendrogram showing the relationship in tree species composition between Switchboard databases (Fig. 3). Here, a pairwise distance matrix of the Simpson dissimilarity measure (βsim; this index efficiently discriminates species turnover from nestedness87) was first constructed. The analysis continued by conducting hierarchical clustering with ‘average’ distance and finalized by reordering the tree by species richness of the databases. Calculations were undertaken with the BiodiversityR88 (version 2.16-1), stats75 (version 4.2.1) and vegan89 (version 2.6-4) R packages. A dendrogram was then constructed via the ggtree81 (version 3.6.2) and ggtreeExtra82 (version 1.8.1) packages with ggplot283 (version 3.5.1), with similar scripts as the cladograms of Figs. 1, 2.

Clustering tree showing similarity in tree species composition (βsim) among databases contributing entries to the Switchboard. The circular heatmap shows the number of tree species native to Africa (1), tropical Asia (2), temperate Asia (3), southern America (4), northern America (5), Australasia (6), Pacific (7) and Europe (8) based on the WCVP. The bar graph shows the number of tree species on a log10 scale within each database’s contribution, colour-coded by the type of database. Refer to text and Tables 1, 2 for database types.

Figure 3 reveals several patterns in species turnover among databases that are in line with expectations. For example, the three invasive species databases form a separate cluster, as anticipated based on the focus of each. Databases focused on specific geographies also tend to cluster, such as the Africa-focused PROTA, AWDD, V4A and UTSA databases, and the temperate-focused EUFORGEN and UTempP. Since GlobUNT was created partially from information extracted from WCUPS, their tight clustering was also expected. A similar situation applies to the GSM and PFAF. Databases focused on human food cluster together, as shown by the arrangement of the AOCC, FoodPlants and FamineFoods databases in the dendrogram. BIOMASS, TropTimber, ComTimber, TheWood, GlobAllome and TFH databases, that all contain information on timber and wood, also form a cluster group. Databases for specific taxa from particular regions do not cluster with each other and only cluster late with other databases, as applies for three LUCID databases (covering Australian rain forest trees, acacias and eucalypts).

Data Records

The Switchboard can be downloaded from a Zenodo archive under a CC-BY 4.0 License90:

Three text files (Table 3) where fields are separated by the pipe ‘|’ character can be directly imported into statistical software environments such as R, or can be pasted into spreadsheets. Also included in the archive is an MS Excel spreadsheet (Switchboard contributing databases.xlsx) that provides metadata for the different databases covered by the Switchboard.

Technical Validation

In addition to the taxonomic standardization approach described above, following a series of manual checks after information for all databases was combined, we resolved various cases of taxa that had been matched with different taxonomic records, but that could afterwards be matched with the same record:

-

Taxa with different matching identities according to the WFO ‘taxonID’ field, but with the same (including spelling variants) name, authority and IPNI fields in the WFO taxonomic backbone, were cross-checked and manually resolved to a single record where possible. Examples included Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile [accepted name; https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000313273] and Balanites aegyptiacus (L.) Delile [accepted name; wfo-0001146307], Acacia macdonnellensis Maconochie [accepted name; wfo-0000202850] and Acacia macdonnelliensis Maconochie [accepted name; wfo-0000202851], and Acalypha alopecuroidea Jacq. [accepted name; wfo-1000054518] and Acalypha alopecuroides Jacq. [accepted name; wfo-0000275337]. As previously, we gave preference to the names matched for GTS and USDA-GRIN. Where neither database listed the species, one matching option was chosen randomly. (Note that the Switchboard also lists the original alternative names for the different databases.)

-

Taxa of the same (including spelling variants) names that were first matched with different matching WFO identities that further included multiple taxonomic statuses (between accepted, synonym and unchecked) were manually matched with a single record. Examples included taxa first matched with Acacia albida Rojas Acosta [unchecked; wfo-1200021925] and Acacia albida Delile [synonym; wfo-0000188059], Austroeupatorium inulifolium (Kunth) R.M.King & H.Rob [unchecked; wfo-1000056230] and Austroeupatorium inulaefolium (Kunth) R.M.King & H.Rob. [accepted; wfo-0000050339], and Sarcocephalus pobeguinii Pobég. [unchecked; wfo-0000303401] and Sarcocephalus pobeguinii Hua ex Pobég [synonym; wfo-0001225760]. We resolved these cases by checking for the accepted name from the online WFO (https://www.worldfloraonline.org/) and POWO (https://powo.science.kew.org/). For example, in the case of Acacia albida, this resulted in it being treated as a synonym of Faidherbia albida in the Switchboard.

-

Taxa with the same accepted name, but with different matching WFO identities, were manually resolved by selecting one of the records. As previously, we gave preference to the authorities matched to the GTS or USDA-GRIN databases. This resolved all cases, except for the following taxa with different records and authorities: Calophyllum polyanthum (wfo-0000581286 with [the authority of] Wall. ex Planch. & Triana and wfo-0001296210 with Wall. ex Choisy); Hippeastrum puniceum (wfo-0001046684 with (Lam.) Kuntze and wfo-0000661183 with (Lam.) Voss); Pluchea sagittalis (wfo-0000016241 with Less and wfo-0000017448 with (Lam.) Cabrera); Prunus emarginata (wfo-0001013841 with (Douglas ex Hook.) Walp. and wfo-0001006712 with (Douglas) Eaton); and Sorbus torminalis (wfo-0000998680 with Garsault and wfo-000101407 with (L.) Crantz). For these taxa, we included different taxonomic identification fields in the Switchboard_4.txt file, but in each case selected the first taxonomic entry (as in the previous sentence) in the Switchboard_species.txt file, to ensure one-to-one matching in the latter file.

The Switchboard_species.txt file provides fields that show the number of potential candidate direct matches between the resolved species name and the records of the WFO backbone (Table 3). Where multiple candidates exist, as is the case for 7,865 species listed by the Switchboard (7.3% of all species), the user may wish to reconfirm matches, especially if this can be done with information on authorities. Similarly, where matching was done manually, as explicitly documented by the Switchboard, users may wish to cross-check the name match.

Usage Notes

The Switchboard’s main objective is to direct the user to multiple information sources for a particular taxon. As taxonomy is a dynamic field, users interested in a particular taxon are encouraged to check for current names via WFO. This can be done using the ‘SID’ field (available from the Switchboard_4.txt and Switchboard_species.txt files, see Table 3) by creating hyperlinks where the ‘SID’ is preceded by “https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/” as for example in https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-1000002958. Users may especially wish to cross-check species that are listed as unchecked in the Switchboard ‘taxonomicStatus’ field, as these could since have been resolved to accepted or synonym status in more recent versions of WFO or WCVP.

Information from the Switchboard can be used internally in other decision-support tools such as GlobUNT7. The metadata contains examples of how taxon-specific hyperlinks can be constructed to different databases. Database developers can create taxon-specific hyperlinks by combining information from the ‘URL_start’ column in the metadata (for the Agroforestree database, ‘https://apps.worldagroforestry.org/treedb2/speciesprofile.php?Spid=’) with information from the ‘Taxon_URL’ field of the Switchboard database, as for an example of the Agroforestree database by creating the hyperlink of: https://www.worldagroforestry.org/treedb2/speciesprofile.php?Spid=18052.

To use the online version of the Switchboard hosted by CIFOR-ICRAF as a central hub for taxon-specific information, users can create an URL-friendly link to the Switchboard application by a naming convention such as https://apps.worldagroforestry.org/products/switchboard/index.php/name_like/Prunus%20africana.

Data from the Switchboard archive can be directly pasted into MS Excel from a text editor after verifying that the file is ‘UTF-8’ encoded. In Excel, the ‘Text to Columns’ option from the ‘Data’ menu then needs to be used with the delimiter of ‘|’ (the pipe character). To import data in R, we recommend using scripts similar to: switch.data <- data.table::fread(file = file.choose(), sep = "|", encoding ="UTF-8").

Code availability

Custom R scripts developed to standardize plant names have been included in the archive.

References

Van Der Plas, F. et al. Biotic homogenization can decrease landscape-scale forest multifunctionality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 3557–3562, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1517903113 (2016).

Dinerstein, E. et al. A “Global Safety Net” to reverse biodiversity loss and stabilize Earth’s climate. Science Advances 6, eabb2824, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abb2824 (2020).

Guo, W.-Y. et al. Climate change and land use threaten global hotspots of phylogenetic endemism for trees. Nature Communications 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42671-y (2023).

Lima, V. P. et al. Integrating climate change into agroforestry conservation: A case study on native plant species in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Journal of Applied Ecology 60, 1977–1994, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14464 (2023).

Brancalion, P. H. S. et al. Using markets to leverage investment in forest and landscape restoration in the tropics. Forest Policy and Economics 85, 103–113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2017.08.009 (2017).

Di Sacco, A. et al. Ten golden rules for reforestation to optimize carbon sequestration, biodiversity recovery and livelihood benefits. Global Change Biology 27, 1328–1348, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15498 (2021).

Kindt, R. et al. GlobalUsefulNativeTrees, a database documenting 14,014 tree species, supports synergies between biodiversity recovery and local livelihoods in landscape restoration. Scientific Reports 13, 12640, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39552-1 (2023).

Bartholomew, D. C. et al. The Global Biodiversity Standard: Manual for assessment and best practices. https://www.biodiversitystandard.org/ (BGCI, Richmond, UK & SER, Washington, DC, USA, 2024).

FAO, SCBD & SER. Delivering restoration outcomes for biodiversity and human well-being – Resource guide to Target 2 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United nations (FAO), the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD) and the Society for Ecological Restoration (SER), 2024).

Lavorel, S. et al. Templates for multifunctional landscape design. Landscape Ecology 37, 913–934, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-021-01377-6 (2022).

Dunlop, T. et al. The evolution and future of research on Nature-based Solutions to address societal challenges. Communications Earth & Environment 5, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01308-8 (2024).

Dawson, I. K. et al. The role of genetics in mainstreaming the production of new and orphan crops to diversify food systems and support human nutrition. New Phytologist 224, 37–54, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15895 (2019).

Pancel, L. Species Files in Tropical Forestry. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41554-8_112-3 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2015).

Holl, K. D., Luong, J. C. & Brancalion, P. H. Overcoming biotic homogenization in ecological restoration. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 37, 777–788, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2022.05.002 (2022).

de Almeida, C., Reid, J. L., de Lima, R. A. F., Pinto, L. F. G. & Viani, R. A. G. High-diversity Atlantic Forest restoration plantings fail to represent local floras. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecon.2024.12.001 (2024).

Borsch, T. et al. World Flora Online: Placing taxonomists at the heart of a definitive and comprehensive global resource on the world’s plants. TAXON 69, 1311–1341, https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.12373 (2020).

Kindt, R. & Pedercini, F. EcoregionsTreeFinder – a global dataset documenting the abundance of observations of > 45,000 tree species in 828 terrestrial ecoregions. Global Ecology and Biogeography 34, e70065, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.70065 (2025).

Brummitt, R. K. World Geographical Scheme for Recording Plant Distributions. Plant Taxonomic Database Standards No. 2, Edition 2. (Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, 2001).

USDA. PLANTS Database. Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture https://plants.usda.gov (2024).

Slee, A. V., Brooker, M. I. H., Duffy, S. M. & West, J. G. EUCLID Eucalypts of Australia Fourth Edition. Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research (CANBR) https://apps.lucidcentral.org/euclid/text/intro/index.html (2020).

Carsan S. et al. African Wood Density Database. World Agroforestry Centre, Nairobi https://apps.worldagroforestry.org/treesnmarkets/wood/data.php (2012).

Orwa, C., Mutua, A., Kindt, R., Jamnadass, R. & Simons A. Agroforestree Database: a tree reference and selection guide. version 4.0. http://www.worldagroforestry.org/af/treedb/ (2009).

CIFOR-ICRAF. CIFOR-ICRAF Tree Genebank: The urgent need to conserve and use trees. https://treegenebank.cifor-icraf.org/index.

Stadlmayr, B., McMullin, S., Innocent, J., Kindt, R. & Jamnadass, R. Priority Food Tree and Crop Food Composition Database: Online database. Version 1. World Agroforestry, Nairobi Kenya https://apps.worldagroforestry.org/products/nutrition/index.php/home/ (2019).

Kindt R. & Innocent J. RELMA-ICRAF Useful Trees Website. http://www.worldagroforestry.org/usefultrees (2016).

Kindt, R. TreeGOER: A database with globally observed environmental ranges for 48,129 tree species. Global Change Biology 29, 6303–6318, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16914 (2023).

Kindt, R. Useful Tree Species for Africa (UTSA). CIFOR-ICRAF https://patspo.shinyapps.io/UsefulTreeSpecies4Africa/ (2023).

Kindt R. et al. Google Earth species distribution maps based on the Vegetationmap4africa map. Version 2.0. World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and Forest & Landscape Denmark https://vegetationmap4africa.org (2015).

Pyšek, P. et al. Scientists’ warning on invasive alien species. Biological Reviews 95, 1511–1534, https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12627 (2020).

CABI. CABI Compendium Invasive Species: Detailed coverage of invasive species threatening livelihoods and the environment worldwide. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/product/QI (2022).

Pagad, S., Genovesi, P., Carnevali, L., Schigel, D. & McGeoch, M. A. Introducing the Global Register of Introduced and Invasive Species. Scientific Data 5, 170202, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.202 (2018).

ISSG. Global Invasive Species Database. IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group https://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/ (2024).

Molina-Venegas, R., Rodríguez, M. Á., Pardo-de-Santayana, M. & Mabberley, D. J. A global database of plant services for humankind. PLoS One 16, e0253069, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253069 (2021).

Barrace, A. et al. Árboles de Centroamérica: un Manual para Extensionistas. https://repositorio.catie.ac.cr/handle/11554/9730 (Oxford Forestry Institute (OFI), Oxford, United Kingdom and Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (CATIE), Turrialba, Costa Rica, 2003).

Réjou‐Méchain, M., Tanguy, A., Piponiot, C., Chave, J. & Hérault, B. BIOMASS: An R package for estimating above‐ground biomass and its uncertainty in tropical forests. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 8, 1163–1167, https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.12753 (2017).

USDA. Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service 1992-2016 http://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/ (2016).

The University of Sussex. eHALOPH: a database of halophytes and other salt-tolerant plants. https://ehaloph.uc.pt/ (2024).

Sanchún, A. et al. Restauración funcional del paisaje rural: manual de técnicas. Vol. XIV, 436 pp. (UICN, San José, Costa Rica, 2016)

Food Plants International. Food Plants International database. https://foodplantsinternational.com/ (2024).

Henry, M. et al. GlobAllomeTree: international platform for tree allometric equations to support volume, biomass and carbon assessment. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 6, 326–330, https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor0901-006 (2013).

PFAF. Plants For A Future. https://pfaf.org/user/Default.aspx (2024).

Jucker, T. et al. Tallo: A global tree allometry and crown architecture database. Global change biology 28, 5254–5268, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16302 (2022).

Mark, J., Newton, A., Oldfield, S. & Rivers, M. A Working List of Commercial Timber Tree Species. (Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, TW9 3BW, UK, 2014).

Diazgranados, M. et al. World Checklist of Useful Plant Species. KNB Data Repository https://kew.iro.bl.uk/concern/datasets/7243d727-e28d-419d-a8f7-9ebef5b9e03e (2020).

Keeler K. H., Porturas, L. D. & Weber, M. G. World list of plants with extrafloral nectaries. http://www.extrafloralnectaries.org/ (2024).

AOCC. Healthy Africa through nutritious, diverse and local food crops: Meet the crops. African Orphan Crops Consortium. https://africanorphancrops.org/meet-the-crops/ (2017).

Zich, F. A., Hyland, B. P. M., Whiffin, T. & Kerrigan, R. A. Australian Tropical Rainforest Plants, Edition 8. https://apps.lucidcentral.org/rainforest/ (2020).

CABI. CABI Compendium Forestry: Detailed coverage of forestry, tree species and forest pests worldwide. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/product/QF (2022).

CABI. CABI Compendium: A leading scientific knowledge resource for environmental and agricultural production, health and biosecurity. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/journal/cabicompendium (2024).

ECHOcommunity. ECHOcommunity Plant Search. https://www.echocommunity.org/en/search/p (2022).

FAO. Database of Crop Constraints and Characteristics. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations https://gaez.fao.org/pages/ecocrop-search (2013).

EUFORGEN. European Forest Genetic Resources Programme: Species. https://www.euforgen.org/species (2024).

Freedman Bob. Famine Foods. https://www.purdue.edu/hla/sites/famine-foods/ (2024).

INRAE, CIRAD, AFZ & FAO. Feedipedia, a programme by INRAE, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://feedipedia.org (2024).

INBAR. INBAR Bamboo and Rattan Species Selection tool. International Bamboo and Rattan Organization https://speciestool.inbar.int/ (2022).

ITTO. Lesser Used Species. International Tropical Timber Organization http://www.tropicaltimber.info/ (2024).

Mansfeld, R. Vorläufiges Verzeichnis landwirtschaftlich oder gärtnerisch kultivierter Pflanzenarten:(mit Ausschluss von Zierpflanzen). Vol. 2, 659 pp. (Die Kulturpflanze, 1962).

Bioversity International. New World Fruits Database. http://nwfdb.bioversityinternational.org/ (2017).

Purdue University. NewCROP. Center for New Crops and Plant Products, Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Purdue University https://hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/default.html (2022).

Stevenson, P. Optimising Pesticidal Plants: Technology Innovation, Outreach and Networks. Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich https://options.nri.org/ (2014).

UO. Oxford Plants 400. Department of Biology, University of Oxford https://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/bol/plants400 (2022).

Verheij, E. W. M. & Coronel, R. E. Plant Resources of South-East Asia. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia https://prosea.prota4u.org/ (2022).

Grubben, G. J. H. & Denton, O. A. PROTA, Plant Resources of Tropical Africa, Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale. Wageningen, Netherlands http://www.prota4u.org (2022).

PPMAC. Portal de Plantas Medicinais, Aromáticas e Condimentares. https://www.ppmac.org/medicinal-aromatica-condimentar (2024).

UCPH. Seed Leaflets. Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management. University of Copenhagen https://sl.ku.dk/rapporter/ (2024).

Elevitch, C. Species profiles for Pacific Island agroforestry. Permanent Agriculture Resources series. Western Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education, Holualoa, Hawaii. https://agroforestry.org/free-publications/traditional-tree-profiles (2006).

Earle, C. J. The Gymnosperm Database. https://www.conifers.org/index.php (2024).

Meier, E. The Wood Database. https://www.wood-database.com/ (2024).

Cook, B. G. et al. Tropical Forages: An interactive selection tool. 2nd and Revised Edn. International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), Cali, Colombia and International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Nairobi, Kenya https://www.tropicalforages.info/text/intro/index.html (2020).

Russell, J. R. et al. tropiTree: An NGS-Based EST-SSR Resource for 24 Tropical Tree Species. PLoS ONE 9, e102502, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102502 (2014).

Ken, F. Temperate Plants Database. https://temperate.theferns.info/ (2024).

Ken, F. Tropical Plants Database. https://tropical.theferns.info/ (2024).

Maslin, B. R. WATTLE, Interactive Identification of Australian Acacia. Version 3. Australian Biological Resources Study, Canberra; Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Perth; Identic Pty. Ltd., Brisbane https://apps.lucidcentral.org/wattle/text/intro/index.html (2018).

Wiersema, J. H. & León, B. World economic plants: a standard reference. (CRC press, 1999).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing https://www.R-project.org/ (2022).

Kindt, R. WorldFlora: An R package for exact and fuzzy matching of plant names against the World Flora Online taxonomic backbone data. Applications in Plant Sciences 8, e11388, https://doi.org/10.1002/aps3.11388 (2020).

Kindt, R. Standardizing tree species names of GlobalTreeSearch with WorldFlora and recent versions of World Flora Online and the World Checklist of Vascular Plants. https://rpubs.com/Roeland-KINDT/1134151 (2023).

Govaerts, R., Nic Lughadha, E., Black, N., Turner, R. & Paton, A. The World Checklist of Vascular Plants, a continuously updated resource for exploring global plant diversity. Scientific Data 8 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00997-6 (2021).

Beech, E., Rivers, M., Oldfield, S. & Smith, P. P. GlobalTreeSearch: The first complete global database of tree species and country distributions. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 36, 454–489, https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2017.1310049 (2017).

Jin, Y. & Qian, H. V. PhyloMaker2: An updated and enlarged R package that can generate very large phylogenies for vascular plants. Plant Diversity 44, 335–339, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2022.05.005 (2022).

Yu, G. Data integration, manipulation and visualization of phylogenetic trees. (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2022).

Xu, S. et al. ggtreeExtra: Compact Visualization of Richly Annotated Phylogenetic Data. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38, 4039–4042, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab166 (2021).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. 2nd edn. Vol. 547, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4 (Springer, New York, 2016).

Kindt, R. TreeGOER 2024 Expansion: Expansion with additional tree and bamboo species identified via the World Checklist of Vascular Plants (v.2024.06). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11208040 (2024).

Keppel, G. et al. Synthesizing tree biodiversity data to understand global patterns and processes of vegetation. Journal of Vegetation Science 32, e13021, https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.13021 (2021).

Kindt, R. et al. The one hundred tree species prioritized for planting in the tropics and subtropics as indicated by database mining. World Agroforestry 312, 01–21, https://doi.org/10.5716/WP21001.PDF (2021).

Baselga, A. Partitioning the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. Global Ecology and Biogeography 19, 134–143, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00490.x (2010).

Kindt, R. & Coe, R. Tree diversity analysis: a manual and software for common statistical methods for ecological and biodiversity studies. (World Agroforestry Centre, 2005)

Oksanen, J. et al. Package ‘vegan’. https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.vegan (2013).

Kindt, R. & John, I. N. Agroforestry Species Switchboard: a synthesis of information sources to support tree research and development activities (v.2025.06). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15628568 (2025).

Schellenberger Costa, D. et al. The big four of plant taxonomy – a comparison of global checklists of vascular plant names. New Phytologist 240, 1687–1702, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18961 (2023).

Kindt, R. TRY 6.0 - Species List from Taxonomic Harmonization – Matches with World Flora Online version 2023.12 (v.2024.10b). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13904173 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the tremendous efforts of the experts who created the databases covered by the Switchboard, as well as those that created taxonomic backbone data sets. We greatly appreciate the assistance provided by Christopher J. Earle in sharing a sitemap of the Gymnosperm database, by Laslo Pancel in sharing the masterlist of the 215 most frequently planted tree species in the tropics as listed in the Tropical Forestry Handbook, and by Jean-Christophe Claudon (ITTO) and Li Yianxia (INBAR) in addressing issues that prevented access to databases hosted by their institutions. CIFOR-ICRAF’s collaborative work with partners on trees receives significant financial support. Support for decision-support tools to enhance tree planting comes from Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative through its funding of the Provision of Adequate Tree Seed Portfolios project (PATSPO); from Germany’s International Climate Initiative through its funding for the Right Tree in the Right Place project (RTRP-Seed); from Darwin Plus (The Overseas Territories Environment and Climate Fund) through its funding of The Global Biodiversity Standard (Grant No. DAREX001); from the Bezos Earth Fund that invests in tree seed and seedling system development in Kenya and the Lake Kivu and Rusizi River Basin; and from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) through its funding of both the IUCN-led Transforming the Eastern Province of Rwanda through Adaptation project (TREPA) and the readiness project on implementing Climate Appropriate Portfolios of Tree Diversity in Burkina Faso (R-CAPTD). In addition, CIFOR-ICRAF gratefully acknowledges the support of the EU and broader CGIAR funding partners. I.S. thanks the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001 through PrInt-CAPES/UFSC of the Postgraduate Program in Plant Genetic Resources (RGV-UFSC). We appreciate the efforts of our colleagues including Ramni Jamnadass in acquiring funding to support decision-support tool development. Finally, we thank our colleague Katrine Friborg and an anonymous reviewer for their useful suggestions on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.K. conceived the dataset, compiled data, conducted data validation, wrote first drafts of the manuscript, created the figures and approved the final ms. R.K. and I.J. collected data. R.K., I.S., I.D., F.P., J.-P.B.L. and L.G. revised the ms.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kindt, R., Siddique, I., Dawson, I. et al. The Agroforestry Species Switchboard, a global resource to explore information for 107,269 plant species. Sci Data 12, 1150 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05492-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05492-w