Abstract

Although crystal parameter prediction from powder X-ray diffraction has recently attracted the interest of the machine learning community, most existing datasets for this task are private and lack structural diversity. Here, we introduce the Simulated Powder X-ray Diffraction Open Database (SIMPOD), a new dataset that is public and structurally varied. This new benchmark includes 467,861 crystal structures from the Crystallography Open Database (COD) and their powder X-ray diffraction patterns. SIMPOD presents simulated one-dimensional powder X-ray diffractograms and derived two-dimensional radial images to facilitate the adoption of computer vision models for this task. We hope SIMPOD contributes to developing models that improve materials analysis from powder X-ray diffraction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Crystal structure determination is fundamental in materials science, particularly when studying previously unreported compounds. In academic contexts, X-ray diffraction is one of the most widely used techniques, with single-crystal and powder X-ray diffraction being the two most common methods1. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction allows for directly determining the three-dimensional crystal structure from a corresponding collection of diffracted data. In contrast, powder X-ray diffraction presents a challenge, as it compresses the three-dimensional information into a one-dimensional pattern2. This compression makes it more challenging to determine the crystal structure unambiguously, especially in the case of organic compounds.

Generally, a crystal structure can be described by symmetry information in the space group, cell parameters, atomic numbers, atomic coordinates, and atomic content. Therefore, determining a crystal structure from powder X-ray diffraction involves retrieving this 3D information from the 1D diffraction pattern2,3. In most cases, this task is performed using direct space approaches that treat the retrieval of 3D information as an optimization problem3. However, these methods have limitations, as the structural search space is prohibitively ample3.

Recently, some authors have explored machine learning techniques for this task. Some works study the prediction of space groups4,5,6,7, cell parameters8 and atomic coordinates9,10. Usually, most of these works employ datasets with diffractograms simulated from files in the Crystallographic Information File (CIF) format4,5,7,9. Nevertheless, in most cases, the CIF datasets are not free to download and lack structural diversity. Some examples include datasets with only inorganic compounds11 and only metal-organic frameworks12,13. In addition, although there are datasets with many crystal structures such as Crystallography Open Database (COD)14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, Materials Project (MP)24 and Cambridge Structural Database (CSD)25, simulating a large volume of powder diffractograms can be expensive in terms of time and computational resources.

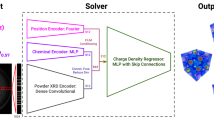

Intending to advance machine learning techniques in this field, we introduce SIMPOD, a dataset comprising 467,861 crystal structures and their corresponding simulated powder X-ray diffractograms in vector and radial-image format (Fig. 1). SIMPOD has a large variety of structures sourced from the COD14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 up to mid-2023. COD is the open-access database that contains the most extensive collection of crystallographic structures of minerals, organic metals, organometallic structures, and small organic compounds26. Furthermore, COD is constantly growing and features crystal structures from donations by individual researchers and peer-reviewed academic press26.

Based on CIF files from the entire COD14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, we created 467,861 JSON files containing individual crystal structures and their corresponding simulated powder diffractograms. Furthermore, we generated radial images in PNG format from the powder diffractograms through a mathematical transformation described in the Methods. The latter was done to facilitate using computer vision models for this problem.

As far as we know, SIMPOD is the first public benchmark for the crystal structure determination task from powder X-ray diffraction. Its size and diversity of structures make it an appropriate dataset for training generalizable models for other essential tasks in materials science, such as crystal parameter prediction (e.g., space groups, unit cells, and atomic coordinates) and crystal structure generation, opening up new possibilities for research and discovery in the field.

Methods

Data extraction and diffractogram simulation

We used COD14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 (https://www.crystallography.net/cod/) until August 2023, which at that date had 498,027 CIF files. We only selected crystal structures with more than 4 atoms in the asymmetric unit to focus the benchmark on structures that are more difficult to determine and up to 256 atoms due to computational cost. In addition, we used Dans Diffraction27, Gemmi28, scikit-image29, and PyAstronomy30 Python packages to filter the database and extract the structural information. Specifically, we obtained an identifier code (ID) in the original dataset, space group, cell parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ), atom types, atomic coordinates, and atomic content of the selected structures. The structural information and corresponding diffractograms were organized and compiled into 467,861 files in JSON format.

The powder diffractograms were simulated using a 2θ range between 5° and 90°, with 10,824 total intensity points (simulating a step size around 0.008°) and default parameters from the Dans Diffraction package, that uses copper (Cu) as the source with a wavelength of 1.5406 Å and 0.01° peak width. By normalizing the diffractograms from their maximum intensity, we constrained all intensity values to be within the [0, 1] interval. These simulation parameters reflect the standard analysis conditions of a conventional diffractometer. Unlike experimental diffractograms, the simulated patterns do not include background and have fixed peak widths, which is a dataset limitation. In addition, the generated patterns correspond to a single X-ray wavelength and a flat detector. Other wavelengths, radiation types (such as neutron diffraction), and detector shapes will produce different patterns, which are not included in this dataset.

Radial images creation

We began by reducing the size of the diffractogram from 10,824 to 1,024 intensities using nearest neighbor interpolation. Following this, we applied a mathematical transformation as described below.

Let \(i\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) be the powder diffractogram defined as i = [i1, i2, … , id] and let x be a vector of integers ranging from − v to v, where \(x\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{s}\) and s = 2v + 1. This vector is defined in equation (1):

Using this, we build a matrix W, where each element wa,b is a function of x as shown in equation (2). We use a constant \(k\in {\mathbb{R}}\) with k > 0 to control the scale of the values in W.

In addition, in equation (3), we define a function I that receives an input matrix and operates it element-wise.

From the matrix W and the function I, we can obtain an image Z = I(W − c) of dimension (s, s), where \(c\in {\mathbb{N}}\) is a constant to control the free space at the center of the image.

For this case, we set v = 260, k = 5, and c = 20. The total approximate data processing time for creating the images and diffractograms was 300 CPU hours. The source code is available at https://github.com/BCV-Uniandes/SIMPOD.git. It is important to note that the radial images could present artefacts along the horizontal and vertical axes derived from the proposed creation process.

Space Group Prediction

A simple example of SIMPOD use is training machine learning models for space group prediction. SIMPOD allows us to perform this task using simulated diffractograms and radial images. In that sense, we trained different traditional machine learning models, such as Distributed Random Forest (DRF) and Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP), using SIMPOD diffractograms and the H2O AutoML library31. Moreover, we trained and optimized several computer vision models, such as AlexNet32, ResNet33, DenseNet34, Swin Transformer35 and Swin Transformer V236, using the radial images and the Pytorch framework37.

The experimentation was done using 2-fold cross-validation, where each fold had 50,000 crystal structures from SIMPOD. In addition, the resulting models were tested in 25,000 crystal structures. The source code is available at https://github.com/BCV-Uniandes/SIMPOD.git. For details on training and optimization of computer vision and H2OAutoML models, see the Supplementary Information.

Experimentation results are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Complete validation results can be found in the Supplementary Information. We see that models employing radial images show the best performance, followed by the models using 1D diffractograms. Thus, we empirically demonstrate the benefits of using deep learning models trained with SIMPOD radial images for this particular task.

Furthermore, we observe an improvement in accuracy and top 5 accuracy in all computer vision models when complexity increases. Figure 2 presents a performance comparison for models with different complexities, highlighting a correlation between Floating Point Operations (FLOPs) per image and accuracy. Moreover, we also see that pretraining benefits model performances. Notably, the average increase in performance when using pretraining is 2.58 ± 0.83% for accuracy and 1.51 ± 0.32% for top 5 accuracy.

As more complex and recent computer vision models demonstrate better results, researchers will benefit from using SIMPOD radial images when training state-of-the-art models. In that sense, SIMPOD represents an important benchmark for addressing different materials science tasks when using powder X-ray diffraction data.

Data Records

SIMPOD is available at Science Data Bank38. The data is organized in 2 folders containing the structural information in JSON format and the images in PNG format. Each JSON file has a dictionary with the ID, the crystallographic information, and the simulated diffractogram of a single structure. The images, named after the ID, are related to each one of the JSON files. It is paramount to mention that SIMPOD has no information about the authors or publications related to the described structures.

Technical Validation

We validated the quality and relevance of the data in five ways. First, we manually reviewed 200 random diffractograms, verifying that their 2θ values and relative intensities were consistent with the respective crystal structure. We employed the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre’s program Mercury39 to explore and analyze the structures. Thus, we used the simulated PXRD patterns from Mercury as the reference, verifying their similarity with the SIMPOD ones.

We observed PXRD pattern consistency in all cases, with excellent matching independent of the structure type. Some examples can be seen in Fig. 3, which shows the structure of a mineral, a coordination complex, and an organic compound together with its SIMPOD and Mercury simulated PXRD patterns, respectively. Therefore, we demonstrate the robustness of the PXRD simulation process along different crystalline compounds.

Simulated diffractograms from Mercury39 and SIMPOD, and crystal structures of (a) Searlesite (NaBSi2O5(OH)), (b) a Bipyridine Palladium Complex (C22H16F3N3OPd) and (c) methyl 5,6-diphenylpyreno[4′,5′:4,5]imidazo[2,1-a]isoquinoline-3-carboxylate (C39H24N2O2).

Second, we proved that the dataset has varied structural types and elemental diversity. By analyzing the distribution of atomic numbers and space groups in all SIMPOD data (Fig. 4), we found that most of them are well represented. Notably, the organic atoms, including hydrogen (H), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and oxygen (O), are the most prevalent, with over 105 structures containing these elements in SIMPOD. This aligns with the fact that organic crystalline compounds present higher molecular diversity than their inorganic counterparts. Additionally, most elements in the periodic table have at least 103 structures and instances in the dataset, ensuring a diverse range of compositions.

On the other hand, we saw that all the space groups are present in SIMPOD, with at least one representative structure. In fact, most space groups have more than 102 instances in SIMPOD, proving crystalline symmetry diversity. Given that COD features a variety of structural types26, it is not surprising that SIMPOD showcases significant structural and compositional diversity.

Third, we proved that COD is well represented in SIMPOD. As the selected structures are a subset of the COD, it is relevant to analyze if the structure selection process generates any structural or compositional biases. Therefore, we also analyze atomic numbers and space group distributions from COD (Fig. 4) and compare them to the SIMPOD ones. Particularly, we calculate the Kullback-Leibler Divergence (KLD) for the normalized distributions.

Taking the COD distributions as a reference, we obtained KLD values of 6.58 ⋅ 10−4 for the atomic distribution per structure, 1.35 ⋅ 10−4 for the atomic distribution in the dataset, and 9.84 ⋅ 10−3 for the space group distribution. Since the KLD for each distribution is low ( < 1 ⋅ 10−2), we demonstrate that SIMPOD is structurally and compositionally similar to COD. It is paramount to note that SIMPOD has fewer instances than COD, which could be relevant when studying less frequent structures (E.g., structures with Helium or Radon).

Fourth, we evaluated the importance of using the proposed images for model training, since we observed that image-trained models had significantly better performance than diffractogram-trained ones. Thus, we tested whether radial images with more resolution and less redundancy, such as those with only a quarter of a circle, changed performance. We created these images by replacing x with \({x}^{{\prime} }=[0,1,2,\cdots \,,2v-1,2v]\) in the process described in the Methods section.

Table 3 shows the results of Swin Transformer V236 models trained with the two versions of radial images. For additional optimization details and validation results, see the Supplementary Information. We observe that the different versions obtain similar results, showing that the image creation is valuable regardless of modality. In that sense, other image-creation approaches could also be used, and we leave exploring other processes for future research.

Fifth, we tested the generalization ability of the AI models trained on SIMPOD’s complete circle radial images using real experimental data. We used 20 experimental diffractograms from compounds with known crystal structures to test the implemented computer vision models. Table 4 shows the results. We hypothesize that real background affected the performance, as this element is not present in our simulated dataset. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the best-performing model achieved a top-5 accuracy of 35% on the experimental data without an expert’s manual peak indexing or background correction. Therefore, even though SIMPOD does not contain experimental diffractograms, it still serves as a valuable benchmark for developing methods that could later be extended to real-world scenarios.

Usage Notes

We strongly suggest following the data loading tutorials available at https://github.com/BCV-Uniandes/SIMPOD.git. We also recommend downloading only the JSON files if images are not needed.

Code availability

The code for creating JSON files and images, tutorials for data loading and data management, and the code for model training are available at https://github.com/BCV-Uniandes/SIMPOD.git.

References

Callister, W. D. Jr. & Rethwisch, D. G. Materials science and engineering: an introduction (John wiley & sons, 2020).

Harris, K. D. & Williams, P. A. Structure determination of organic molecular solids from powder x-ray diffraction data: current opportunities and state of the art. Advances in Organic Crystal Chemistry: Comprehensive Reviews 2015 141–166, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55555-1_8 (2015).

Harris, K. D., Tremayne, M. & Kariuki, B. M. Contemporary advances in the use of powder x-ray diffraction for structure determination. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 40, 1626–1651 (2001).

Park, W. B. et al. Classification of crystal structure using a convolutional neural network. IUCrJ 4, 486–494, https://doi.org/10.1107/S205225251700714X (2017).

Lee, B. D. et al. Powder x-ray diffraction pattern is all you need for machine-learning-based symmetry identification and property prediction. Advanced Intelligent Systems 4, 2200042, https://doi.org/10.1002/aisy.202200042 (2022).

Suzuki, Y. et al. Symmetry prediction and knowledge discovery from x-ray diffraction patterns using an interpretable machine learning approach. Scientific reports 10, 21790, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77474-4 (2020).

Lee, B. D. et al. A deep learning approach to powder x-ray diffraction pattern analysis: Addressing generalizability and perturbation issues simultaneously. Advanced Intelligent Systems 5, 2300140, https://doi.org/10.1002/aisy.202300140 (2023).

Li, Y., Yang, W., Dong, R. & Hu, J. Mlatticeabc: generic lattice constant prediction of crystal materials using machine learning. ACS omega 6, 11585–11594, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c00781 (2021).

Guo, G. et al. Towards end-to-end structure determination from x-ray diffraction data using deep learning. npj Computational Materials 10, 209, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01401-8 (2024).

Lai, Q. et al. End-to-end crystal structure prediction from powder x-ray diffraction. Advanced Science 12, 2410722, https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202410722 (2025).

Zagorac, D., Müller, H., Ruehl, S., Zagorac, J. & Rehme, S. Recent developments in the inorganic crystal structure database: theoretical crystal structure data and related features. Journal of applied crystallography 52, 918–925, https://doi.org/10.1107/S160057671900997X (2019).

Wilmer, C. E. et al. Large-scale screening of hypothetical metal–organic frameworks. Nature chemistry 4, 83–89, https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.1192 (2012).

Bobbitt, N. S. et al. Mofx-db: An online database of computational adsorption data for nanoporous materials. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data 68, 483–498, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jced.2c00583 (2023).

Crystallography open database. https://www.crystallography.net/cod/.

Vaitkus, A. et al. A workflow for deriving chemical entities from crystallographic data and its application to the Crystallography Open Database. Journal of Cheminformatics 15, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-023-00780-2 (2023).

Merkys, A. et al. Graph isomorphism-based algorithm for cross-checking chemical and crystallographic descriptions. Journal of Cheminformatics 15, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-023-00692-1 (2023).

Vaitkus, A., Merkys, A. & Gražulis, S. Validation of the Crystallography Open Database using the Crystallographic Information Framework. Journal of Applied Crystallography 54, 661–672, https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600576720016532 (2021).

Quirós, M., Gražulis, S., Girdzijauskaitė, S., Merkys, A. & Vaitkus, A. Using SMILES strings for the description of chemical connectivity in the Crystallography Open Database. Journal of Cheminformatics 10, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-018-0279-6 (2018).

Merkys, A. et al. COD::CIF::Parser: an error-correcting CIF parser for the Perl language. Journal of Applied Crystallography49, https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600576715022396 (2016).

Gražulis, S., Merkys, A., Vaitkus, A. & Okulič-Kazarinas, M. Computing stoichiometric molecular composition from crystal structures. Journal of Applied Crystallography 48, 85–91, https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600576714025904 (2015).

Gražulis, S. et al. Crystallography open database (cod): an open-access collection of crystal structures and platform for world-wide collaboration. Nucleic Acids Research 40, D420–D427, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr900 (2012).

Gražulis, S. et al. Crystallography Open Database – an open-access collection of crystal structures. Journal of Applied Crystallography 42, 726–729, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889809016690 (2009).

Downs, R. T. & Hall-Wallace, M. The american mineralogist crystal structure database. American Mineralogist 88, 247–250 (2003).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The materials project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Materials 1, 011002, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4812323 (2013).

The cambridge structural database. https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/solutions/software/csd/.

Gražulis, S., Merkys, A. & Vaitkus, A. Crystallography open database (cod). In Andreoni, W. & Yip, S. (eds.) Handbook of Materials Modeling: Methods: Theory and Modeling, vol. 3, 1863–1881, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44677-6_66 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2020).

Porter, D. & Prestipino, C. Danporter/dans_diffraction: Version 3.0.0. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8106031 (2023).

Wojdyr, M. Gemmi: A library for structural biology. Journal of Open Source Software 7, 4200, https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.04200 (2022).

Van der Walt, S. et al. scikit-image: image processing in python. PeerJ 2, e453, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.453 (2014).

Czesla, S. et al. PyA: Python astronomy-related packages. Astrophysics Source Code Library (2019).

LeDell, E. & Poirier, S. H2O AutoML: Scalable automatic machine learning. 7th ICML Workshop on Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) (2020).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Pereira, F., Burges, C., Bottou, L. & Weinberger, K. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 25 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2012).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 770–778 (2016).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2261–2269 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 9992–10002 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer v2: Scaling up capacity and resolution. In 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 11999–12009 (2022).

Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Wallach, H.et al. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 32 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2019).

Rincón, S., González, G., Macías, M. A. & Arbeláez, P. SIMPOD: Simulated Powder X-ray diffraction Open Database. Science Data Bank, https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.09755 (2025).

Macrae, C. F. et al. Mercury 4.0: From visualization to analysis, design and prediction. Applied Crystallography 53, 226–235 (2020).

Acknowledgements

All authors acknowledge financial support provided by the Vice Presidency for Research & Creation publication fund at the Universidad de los Andes. In addition, we thank the Center for Research and Formation in Artificial Intelligence (CinfonIA) and the Vice Presidency for Research & Creation for providing the computational resources used for this research. We also thank Leopoldo Suescun for sharing experimental diffractograms and their corresponding structures. Moreover, we thank the support from the Department of Chemistry at Universidad de los Andes. Last, we thank Leonardo Manrique for the scientific discussion regarding the radial images.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.R. managed the data, wrote the code, performed experiments, and wrote the manuscript. G.G. wrote the code, performed experiments, and wrote the manuscript. M.M. managed the data and reviewed the manuscript. P.A. reviewed the manuscript and planned the experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rincón, S., González, G., Macías, M.A. et al. A new benchmark for machine learning applied to powder X-ray diffraction. Sci Data 12, 1186 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05534-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05534-3