Abstract

The perinatal period (from late gestation to the neonatal stage) in ruminants is a critical phase for fetal organ maturation, where ecological succession of gastrointestinal microbial communities significantly impacts livestock production efficiency. However, research remains insufficient regarding the distribution patterns and functional annotation of microbial communities across different gastrointestinal compartments during this period. This study characterized early microbiota dynamics in Hutianshi Goats using 16S rRNA sequencing (4 fetal goats at 90 ± 10 gestational days) and metagenomics (3 7-day-old goat kids). The fetal goat group generated 852,694 valid reads, yielding 688,277 high-quality reads after chimera removal for downstream analysis. The 7-day-old goat kids group produced 1,081,588,182 final valid reads, after data processing and assembly, 8,561,345 contigs were generated. Gene prediction identified 6,095,352 genes. Multi-database annotations (NR, KEGG, CAZy, etc.) revealed functional potential and antimicrobial resistance traits. The public release of this dataset facilitates academic understanding of microbial community dynamics and host-microbe interactions during this developmental stage, providing both theoretical foundations and data resources for ruminant developmental biology and precision breeding regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The gastrointestinal microbiota are vast in number and diverse in composition1,2. Compared to monogastric animals, ruminant gastrointestinal microbiota exhibit higher diversity3. Studies have shown4 that the gut microbiota of ruminants mainly consists of bacteria, fungi, archaea, and viruses, with bacteria being the most abundant, accounting for approximately 80% of the total microbial population in the gut5. The gut microbiome is an important regulatory factor in host health and physiological functions, playing a critical role in the host’s growth and development6, nutritional metabolism7,8, immune regulation9,10,11, and disease resistance12,13. Goats, as important livestock with strong adaptability and high economic value, have been shown to have a strong correlation between their rumen or intestinal microbiota and the fatty acids in their longissimus dorsi muscle, revealing specific bacteria associated with these fatty acids14. The gastrointestinal microbiota of goats significantly affects the digestibility of dietary calcium, with Prevotella species in the rumen being beneficial to the digestion of dietary calcium, supporting normal physiological functions and growth15. However, previous research has mainly focused on the rumen and intestinal microbiota of adult goats, emphasizing the impact of microbial communities on the health and production performance of mature animals. In contrast, studies on the microbiota of fetal and young goats are limited, especially regarding the establishment of gastrointestinal microbiota during the fetal stage and the early microbial community’s impact on goat growth and development, which restricts our understanding of microbial dynamics throughout the goat’s life cycle and its early effects on immunity and nutrient absorption.

With the advancement of molecular biology techniques, researchers have utilized high-throughput sequencing to analyze the gut microbiota community structure of ruminants under various breeds, growth stages, and feeding environments16. 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomic sequencing have become essential tools for studying microbiota community structure and function. Studies have found that factors such as breed17, age18, and feeding environment19 influence the composition of animal gastrointestinal microbiota. Metagenomic sequencing, which involves sequencing the total DNA of microbial communities, provides a comprehensive understanding of microbiota structure and function, uncovering functional genes and metabolic pathways, and revealing the relationship between microbiota and host growth and development20, as well as disease occurrence21. Currently, 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomic sequencing are widely used in gastrointestinal microbiota research.

Recent advances in agricultural microbiome research underscore the value of cross-species methodological integration. For instance, Wang et al. employed metagenomics to constructed a chicken multi-kingdom microbiome catalog (CMKMC)22, while our study establishes a dataset combining 16S rRNA sequencing (fetal goat) and metagenomics (7-day-old goat). This dual approach addresses technical challenges in low-biomass fetal environments while enhancing functional insights in neonates. Both studies focused on the host gut microbiome, with bacteria dominating during initial colonization. The eukaryotic microbial catalog from Wang et al. further aids annotation of eukaryotic signals in our dataset, whereas our protocols for prenatal sampling offer methodological insights for embryonic microbiome studies.

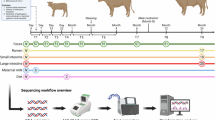

This study focuses on the 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the two stomachs (rumen and reticulum) as well as the large and small intestines of fetal Hunan local goats (Hutianshi Goat). Additionally, metagenomic sequencing was performed on the contents of the four stomachs (rumen, omasum, abomasum, and reticulum) and the large intestine (cecum, rectum, colon) and small intestine (ileum, jejunum) of 7-day-old goat kids. Understanding the interaction mechanisms between gut microbiota composition and ruminant health status will help in developing effective preventive and management strategies. The generation of these data provides an important molecular basis for understanding the interaction mechanisms between goat gastrointestinal microbiota and their host. This study provides the 16S rRNA sequencing data of fetal goat gastrointestinal microbiota (PRJNA1159466) and metagenomic sequencing data of 7-day-old goat kid gastrointestinal microbiota (PRJNA1160040). These datasets not only enrich the microbiome database of Hunan local goats but also provide solid data support for future functional gene research, microbiota-host interaction mechanism analysis, and precision breeding strategies. By making these high-quality microbiome data publicly available, we aim to promote further academic understanding of goat gastrointestinal microbiota ecology, foster healthy farming practices, and encourage sustainable development in animal husbandry. Additionally, these data provide a valuable reference resource for livestock microbiome research globally and hold significant application prospects and scientific value.

Methods

Ethical declaration

Animal handling and experimental procedures were approved by the animal protection and utilization committee of Hunan Agricultural University (protocol number: HAU ACC 2022120). All animal treatments and experiments comply with the guidelines for ethical review of animal welfare in the national standards of the People’s Republic of China (151). This study does not involve any endangered or protected species, so no additional specific permits are required in addition to standard ethical approvals.

Experimental animal sample collection and DNA

All animals in this study were sourced from the Hutianshi Goat breeding farm in Xiangtan City. Details of the sample classification and its sequence reading counts are shown in Tables 1, 2. The content of Table 1 includes the individuals of the fetal goat group, the sample name labels, the number of effective sequences obtained from denoising the contents of each part of the fetal goat through 16S rRNA sequencing, and the quantity of high-quality sequences after removing chimeras. The content of Table 2 includes the individual and sample name annotations for the 7-day-old goat kid group, the number of final effective reads obtained from metagenomic sequencing of the contents from various parts of the 7-day-old goat kid, the number of contigs generated after data processing and assembly, the number of genes predicted, and the number of Genesets obtained after redundancy removal. The Hutianshi Goats were all raised under standard conditions with free access to water and feed. Six adult (720 ± 30 days) female goats (22.37 ± 4.93 kg) with similar body weights were selected at 90 ± 10 days of pregnancy. They were fasted for 12 hours before slaughter, with free access to water. At the Hutianshi Goat slaughterhouse, experienced personnel performed anesthesia and exsanguination according to commercial practices, followed by skinning. Contents from the reticulum, rumen, small intestine, and large intestine of four fetal goats were collected, totaling 13 samples, which were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80 °C in a freezer. Subsequently, under the same feeding conditions, three 7-day-old goat kids were randomly selected for slaughter and sampling. Professional personnel collected contents from the four stomachs (rumen, omasum, abomasum, and reticulum), large intestine (cecum, colon, and rectum), and small intestine (ileum and jejunum) of each goat kid, yielding a total of 27 samples, which were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and transported back to the laboratory for storage at −80 °C. All experimental procedures involving goats in this study were conducted in strict compliance with the Guidelines for Ethical Review of Experimental Animal Welfare and institutional protocols. The research protocol underwent formal review and approval by the Animal Experimental Ethics Committee of Hunan Agricultural University (protocol number: HAU ACC 2022120) to ensure adherence to ethical principles. The DNA extraction was performed using the TGuide S96 magnetic bead-based soil/fecal genomic DNA extraction kit.

DNA sequencing

For 16S rRNA sequencing, the TruSeq Nano DNA LT Library Prep Kit from Illumina was used to prepare the sequencing library, and paired-end sequencing of the community DNA fragments was performed on the Illumina MiSeq/NovaSeq platform. For metagenomic sequencing, the VAHTS™ Universal Plus DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina was used to prepare the library. The constructed libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, with a sequencing strategy of PE150. The raw sequencing data were provided in FASTQ format, with quality control and trimming performed by the sequencing laboratory. The taxonomic identification and species abundance data of non-redundant high-quality bins are provided in attachments 1–2.

Bioinformatics analysis

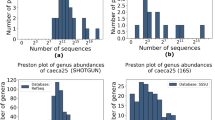

We performed bioinformatics analysis on both 16S rRNA and metagenomic data. Raw data from high-throughput sequencing were first screened based on sequence quality, and problematic samples were re-sequenced or supplemented. The sequences passing the initial quality filter were sorted by index and barcode information, and the barcode sequences were removed. Sequence denoising or OTU clustering was performed according to the QIIME2 dada2 pipeline or the Vsearch software23 pipeline. Specifically, for the QIIME2 analysis (version 2019.4), the qiime cutadapt trim-paired command was used to trim primer sequences, discarding sequences that did not match primers. Then, qiime dada2 denoise-paired was used to perform quality control, denoising, joining, and chimera removal via DADA2. For bacterial or archaeal 16S rRNA genes, the Greengenes database (Release 13.8, http://greengenes.secondgenome.com/) was the default reference database24, though the Silva database (Release 132, http://www.arb-silva.de) can also be used25. The classify-sklearn algorithm in QIIME226 (https://github.com/QIIME2/q2-feature-classifier) was applied for species annotation of each ASV or representative sequence of each OTU using the pre-trained Naive Bayes classifier with default parameters.

For metagenomic data, raw reads obtained from sequencing were subjected to quality control using fastp27 and bowtie228, resulting in clean reads for subsequent bioinformatics analysis. These clean reads were assembled, and coding genes were predicted to construct a non-redundant gene set. The non-redundant gene set was then annotated for function and taxonomy using both general and specialized databases, and species composition and abundance were assessed. Metagenomic assembly was performed using MEGAHIT29, with contig sequences shorter than 300 bp being filtered out. The assembly results were evaluated using the QUAST software30. Gene prediction was performed using MetaGeneMark31 (http://exon.gatech.edu/meta_gmhmmp.cgi, Version 3.26) with default parameters to identify coding regions in the genome. Redundancy was removed from the protein sequences using MMseqs 232 (https://github.com/soedinglab/mmseqs2, Version 12-113e3), setting the protein sequence similarity threshold to 90% and the coverage threshold to 80%, thus constructing a non-redundant gene set.

Metagenomic functional annotation was carried out by aligning the sequences with general database such as NR (Non-Redundant Protein Database), GO (Gene Ontology), KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes), eggNOG (Evolutionary Genealogy of Genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups), Pfam (Protein Families Database), SwissProt, and special database such as CAZy (Carbohydrate-active Enzymes Database), CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Research Database), PHI-base (Pathogen Host Interactions Database), CYPED (The Cytochrome P450 Engineering Database), QS (Quorum Sensing), and BacMet (Antibacterial Biocide And Metal Resistance Genes Database). Table 3 provides detailed annotation information, including the number of genes annotated into each database.

BLASTP was used to analyze the NCBI non-redundant protein database. For annotation, the protein sequences of the non-redundant genes were subjected to BLAST alignment with the corresponding database (e-value set to 1e-5). The most similar sequence in the respective database was identified, and the annotation information corresponding to that sequence was used as the annotation for the sequencing genome gene. The database was constructed from the assembled metagenomic sequences of the combined samples. All reported aligned sequences were further subjected to a reverse BLASTN search in the NCBI non-redundant nucleotide database. Based on the alignment results from the non-redundant gene to the corresponding database, the corresponding annotation information was considered as the annotation for the sequencing genome genes.

Method and Cohort limitations

While this dual-sequencing study provides initial insights into microbial colonization shifts from prenatal to neonatal ruminants, several analytical constraints require acknowledgment: (1) Taxonomic resolution discordance between 16S rRNA (genus-level) and metagenomic (species-level) profiling complicates cross-developmental continuity assessments. (2) Restricted fetal cohort size (n = 3) may underpower rare taxa detection (<0.01% abundance) and inflate individual variation bias. These inherent challenges in developmental microbiome research highlight the necessity for longitudinal designs integrating synchronized multi-omics and expanded cohorts.

Data Records

The sequencing data used in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA). The assembled metagenomic data are available under the NCBI accession number PRJNA1160040, the SRA under accession number SRR30679764, SRR30679765, SRR30679766, SRR30679767, SRR30679768, SRR30679769, SRR30679770, SRR30679771, SRR30679772, SRR30679773, SRR30679774, SRR30679775, SRR30679776, SRR30679777, SRR30679778, SRR30679779, SRR30679780, SRR30679781, SRR30679782, SRR30679783, SRR30679784, SRR30679785, SRR30679786, SRR30679787, SRR30679788, SRR30679789, SRR3067979033. Additionally, the 16S rRNA sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI SRA under the accession number PRJNA1159466 and the SRA under accession number SRR30634697, SRR30634698, SRR30634708, SRR30634719, SRR30634725, SRR30634726, SRR30634727, SRR30634728, SRR30634729, SRR30634730, SRR30634731, SRR30634741, SRR3063474234.

Technical Validation

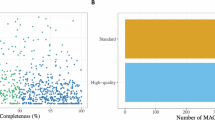

The raw reads from 16S rRNA sequencing was first mass filtered using Trimmomatic, followed by primer sequence identification and removal using Cutadapt. Later, for the clustering method, “denoising (dada2)” was selected, and the dada2 package in R was used for further quality control, splicing of double-ended reads, and removal of chimeras. For the clustering method, we chose “similarity clustering”, and we used USEARCH to splice the double-ended reads and remove the chimeras (UCHIME, resulting in high-quality sequences for subsequent analysis. The raw reads obtained by metagenomic sequencing contain low-quality sequences, and the parameters −5 -W 50 -M 20 -l 60 -n 0 -g -A need to be used to filter the raw reads to obtain high-quality clean reads, and the parameters --seed 123456 -I 200 -X 1000 --un-conc-gz are used to align with the host genome sequence. Host contamination (https://asia.ensembl.org/Capra_hircus/Info/Index, Capra_hircus V1.0) is removed for subsequent information analysis. As shown in Fig. 1, as the amount of sequencing increases, the Observed_species index curve approaches flattening, indicating that the sequencing depth is sufficient to reflect the vast majority of microbial information in the sample.

Rarefaction Curve. (a) Rarefaction curves of fetal goat. The x-axis represents the sequencing depth, and the y-axis shows the boxplot of the Observed_species index calculated 10 times. (b) Rarefaction curves of fetal goat. The x-axis represents the amount of sequencing data randomly sampled; the y-axis represents the number of observed OTUs; this indicates that the number of OTU species measured at the same sequencing depth differs among different samples.

Code availability

Trimmomatic version 0.33

Cutadapt version 1.8.3

Usearch version 10

Uchime version 8.1

Fastp version 0.23. 1

Bowtie2 version 2.2.4

Vsearch version 2.4.3

QIIME2 versoin 2020.6

Greengenes version 13.5

Blastn version 2.9.0

Megahit version 1. 1.2

Quast version 2.3

MetaGeneMark version 3.26

MMseq. 2 version 11-e1a1c

Diamond version 0.9.29

Hmmer version 3.0

References

Moran, E. T. & Bedford, M. R. Endogenous mucin conveyed to the mucosa with microbes can assure lumen fermentation and large intestinal security-swine versus fowl. Anim Nutr. 14, 403–410 (2023).

Zoumpopoulou, G. et al. Probiotics and prebiotics: an overview on recent trends. Probiotics and prebiotics in animal health and food safety, 1–34 (2018).

Mi, J. et al. A metagenomic catalogue of the ruminant gut archaeome. Nat Commun. 15(1), 9609 (2024).

Xie, F. et al. An integrated gene catalog and over 10,000 metagenome-assembled genomes from the gastrointestinal microbiome of ruminants. Microbiome. 9(1), 137 (2021).

Sun, X. et al. Microbial community composition in the dung of five sympatric European herbivore species. Ecol Evol. 14(3), e11071 (2024).

Cheng, J. et al. Relationship between rumen microbial differences and traits among Hu sheep, Tan sheep, and Dorper sheep. J Anim Sci. 100(9), skac261 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Bacterial Community Diversity Associated With Different Utilization Efficiencies of Nitrogen in the Gastrointestinal Tract of Goats. Front Microbiol. 10, 239 (2019).

Hashimoto, N. et al. Lithocholic acid increases intestinal phosphate and calcium absorption in a vitamin D receptor dependent but transcellular pathway independent manner. Kidney Int. 97(6), 1164–1180 (2020).

Firkins, J. L. & Yu, Z. RUMINANT NUTRITION SYMPOSIUM: How to use data on the rumen microbiome to improve our understanding of ruminant nutrition. J Anim Sci. 93(4), 1450–70 (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. Differences in meat quality between Angus cattle and Xinjiang brown cattle in association with gut microbiota and its lipid metabolism. Front Microbiol. 13, 988984 (2022).

Fan, P. et al. Host genetics exerts lifelong effects upon hindgut microbiota and its association with bovine growth and immunity. ISME J. 15(8), 2306–2321 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Recent insights and advances in gut microbiota’s influence on host antiviral immunity. Front Microbiol. 16, 1536778 (2025).

Jiao, J. et al. Shifts in Host Mucosal Innate Immune Function Are Associated with Ruminal Microbial Succession in Supplemental Feeding and Grazing Goats at Different Ages. Front Microbiol. 8, 1655 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Preliminary Investigation of Mixed Orchard Hays on the Meat Quality, Fatty Acid Profile, and Gastrointestinal Microbiota in Goat Kids. Animals (Basel). 12(6), 780 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Relationship between the True Digestibility of Dietary Calcium and Gastrointestinal Microorganisms in Goats. Animals (Basel). 10(5), 875 (2020).

Pitta, D. W. et al. Rumen bacterial diversity dynamics associated with changing from bermudagrass hay to grazed winter wheat diets. Microb Ecol. 59(3), 511–22 (2010).

Lu, H. et al. Comparative Study of Bacterial Microbiota Differences in the Rumen and Feces of Xinjiang Brown and Holstein Cattle. Animals (Basel). 14(12), 1748 (2024).

Maffei, V. J. et al. Biological Aging and the Human Gut Microbiota. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 72(11), 1474–1482 (2017).

Henderson, G. et al. Rumen microbial community composition varies with diet and host, but a core microbiome is found across a wide geographical range. Sci Rep. 5, 14567 (2015).

Jami, E. et al. Exploring the bovine rumen bacterial community from birth to adulthood. ISME J. 7(6), 1069–79 (2013).

de Flamingh, A. et al. Combining methods for non-invasive fecal DNA enables whole genome and metagenomic analyses in wildlife biology. Front Genet. 13, 1021004 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. The multi-kingdom microbiome catalog of the chicken gastrointestinal tract. Biosaf Health. 6(2), 101–115 (2024).

Edgar, R. C. et al. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 27(16), 2194–200 (2011).

DeSantis, T. Z. et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol. 72(7), 5069–72 (2006).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41(Database issue), D590–6 (2013).

Bokulich, N. A. et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. 6(1), 90 (2018).

Chen, S. et al. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 34(17), i884–i890 (2018).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 9(4), 357–9 (2012).

Li, D. et al. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics. 31(10), 1674–6 (2015).

Gurevich, A. et al. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 29(8), 1072–5 (2013).

Zhu, W., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. Ab initio gene identification in metagenomic sequences[J]. Nucleic Acids Res. 38(12), e132 (2010).

Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. MMseqs 2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat Biotechnol. 35(11), 1026–1028 (2017).

NCBI Sequence read archive https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/SRP532984 (2024).

NCBI Sequence read archive https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/SRP532093 (2024).

Cantarel, B. L. et al. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37(Database issue), D233–8 (2009).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 25(1), 25–9 (2000).

Jia, B. et al. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(D1), D566–D573 (2017).

Kanehisa, M. et al. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 32(Database issue), D277–80 (2004).

Winnenburg, R. et al. PHI-base: a new database for pathogen host interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 34(Database issue), D459–64 (2006).

Powell, S. et al. eggNOG v4.0: nested orthology inference across 3686 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(Database issue), D231–9 (2014).

Fischer, M. et al. The Cytochrome P450 Engineering Database: a navigation and prediction tool for the cytochrome P450 protein family. Bioinformatics. 23(15), 2015–7 (2007).

Mistry, J. et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49(D1), D412–D419 (2021).

Bairoch, A. & Apweiler, R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence data bank and its new supplement TREMBL. Nucleic Acids Res. 24(1), 21–5 (1996).

Pal, C. et al. BacMet: antibacterial biocide and metal resistance genes database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(Database issue), D737–43 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Key R&D Program of Hunan Province (2023DK2004), the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFD1300503), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32002166).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Peng Huang, Mei Liu and Wenmeng Jiang conceived and designed the experiments. Wenmeng Jiang, Rongsheng Xi, Junjuan Zhou, and Yu Pei conducted the experiments. Mei Liu and Wenmeng Jiang analyzed the data. Junjuan Zhou was deeply involved in the revision and writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, W., Xi, R., Zhou, J. et al. 16S rRNA and Metagenomic Datasets of Gastrointestinal Microbiota in Fetal and 7-Day-Old Goat Kids. Sci Data 12, 1234 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05555-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05555-y