Abstract

Mapping spatiotemporal dynamics of crop-specific areas is of great significance in addressing challenges faced by agricultural systems. But comparable multi-phase crop maps in year series have not yet been developed in most regions of the global. In this study, we developed a framework for updating annual crop-specific area maps at 10 km resolution based on crop statistics disaggregating, multi-source data integrating and machine learning. In our framework, we collected related spatial indicator used in previous studies and trained random forest regression models to predict spatiotemporal dynamics of crop-specific areas based on them. Annual crop statistics were further disaggregated based on probabilistic layer and harmonized based on multiple constraints. Finally, our results include maps of crop-specific areas covering 42 types from 1961–2022 in Africa, maps of crop-specific areas covering 14 types from 1980–2022 in China. Results show that our products have a reasonable level of consistency with independent reference map or statistics. Our products could be used as data basis for food security and environmental impact assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

As the largest land use in the world, agriculture is at the heart of many global problems, for it has greatly changed the biosphere in terms of land use change, freshwater use, nitrogen cycle and biodiversity1,2,3,4. On the one hand, agricultural system is faced by higher food production demands coming with the continuous growth of population and higher proportion of high-protein foods in people’s diet5,6; On the other hand, agriculture is a driving factor behind many global environmental issues, such as deforestation and resulting carbon emissions7, climate change8, biodiversity loss9, etc. At the same time, agricultural production is also adversely affected by climate change10, epidemic outbreak11, war and conflict12, and urbanization encroachment13,14. Obtaining sufficient and detailed data basis is the prerequisite to deal with challenges and carry out decision analysis. Many studies have successfully mapped the distribution of global agricultural land in multiple time periods15,16,17,18, but the diversity of global agricultural planting systems has not been fully detailed19,20. Mapping spatiotemporal dynamics of crop-specific areas is of great significance in addressing the above challenges4. Human needs for different crops vary according to their use, nutritional value and cultural factors. Food security is not only about providing sufficient calories, but also about meeting people’s nutritional needs and dietary preferences21. Meanwhile, crop type mapping provides more information about the ecological and environmental impacts of agriculture and the threats it faces7,9.

Global crop distribution information is uneven in time and space (Table S1, Fig. S1). Despite operational monitoring and remote sensing mapping in some countries in recent years22,23, there is still a lack of spatially explicit data sets for crop planting history. In most parts of the world, crop distribution information tends to come only from national or subnational scale statistics (Fig. S1), which greatly limits the use of data24. Therefore, many studies have developed crop maps by spatially allocating crop statistics based on cropland maps over the past two decades. These crop distribution maps often have large-scale spatial coverage (usually global coverage), but coarse spatial resolution (such as 5 arc minutes, about 10 km). As early as 2004, Leff et al. (2004) allocated the statistics of 18 crops to the global 5-arc grids in 1990s by a simplified proportional disaggregating approach25. Specifically, this method obtained a crop distribution map by calculating the proportion of the crop-specific harvested area in the total at the administrative unit level and multiplying it by the cropland proportion within the grid. By adopting this approach, Monfreda et al. (2008) developed the global harvested area and yield distribution map of 175 crops in 2000 (M3) with more detailed statistical data2. On the basis of M3, Portmann et al. (2010) further combined additional data such as irrigated area, crop calendar to produce monthly irrigated and rainfed crop areas around the year 2000 (MIRCA)26.

However, in the first few global crop distribution maps, the harvested area of crops in administrative units is equally distributed proportionally, ignoring the diversity and difference of crop distribution in different regions and complex agricultural systems. By considering climatic and edaphic suitability of crops, GAEZ products (Global Agro-ecological Zones) provides new estimates of potential crop-specific areas of 23 crops27. Moreover, the Spatial Production Allocation Model (SPAM) is a new spatial allocation model of crop statistics by disaggregation at farming systems and optimization using a cross-entropy algorithm, also taking many related factors into account such as crop suitability, market accessibility and crop revenue, which greatly increases the complexity of model input and allocation process19,20,28,29. However, the differences in crop-specific harvested area estimated by each model are significant, mostly resulting from differences in the input datasets and downscaling methodologies30.

As multiple sets of crop-type mapping products based on remote sensing have been produced and widely used, crop distribution information in these regions has a more accurate and timely spatial representation. Some studies have adopted the scoring rule-based approach to integrate multi-source crop maps. For example, Becker-Reshef et al. (2023) built a scoring system based on five indicators and updated more accurate crop distribution information of 66 countries in the world based on SPAM2010 map31. Besides, Tang et al. (2024) developed CROPGRIDS, an updated crop distribution dataset for around 2020, based on the 2000 M3 map by integrating 27 sets of existing crop mapping products and new crop statistics using scoring rules32.

Among the above global crop distribution mapping products, GAEZ, SPAM and MIRCA-OS has multi-period map products20,27,33,34. But the comparison of multi-period maps across time stages proved to be inappropriate. Although the research team ensured the spatial accuracy of each map as much as possible, system errors of various data sources were inevitably included in the integration process20. In order to better understand temporal trends of crop distribution, many studies have moved beyond static multi-year crop maps and have focused instead on developing mapping products with annual updates. For example, Ray et al. (2012) plotted the planting area and yield change trend of maize, rice, wheat and soybean during 1961–2008 based on the of national or subnational crop statistics35. However, collecting statistics at the subnational level takes a lot of manpower and time, especially when covering multiple crop types36. Jackson et al. (2019) developed a new allocation algorithm called the Probabilistic Cropland Allocation Model (PCAM), which allocated crop statistic at national level based on suitability probability clusters and multiple Monte Carlo37. Mapping result covers 17 crops from 1961 to 2014, but it is regarded more as only likely changes in the spatial distribution. Based on temporally dynamic spatial indicators, machine learning algorithms provide new possibilities for the annually update of crop distribution maps. Factors such as precipitation, temperature, and soil characteristics are widely used to build crop suitability models and generate time-series products38,39. Machine learning (deep learning) algorithms are regarded as an alternative to the cross-entropy method used in SPAM product development and have demonstrated better performance39,40,41,42.

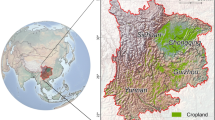

Inspired by previous studies, our study aims to develop a framework for updating annual crop-specific area maps based on crop statistics disaggregating, multi-source data integrating and machine learning, taking factors related to crop distribution in different regions and complex agricultural systems into account. We selected three regions as study areas, respectively Africa, China, and USA (only for validation). They correspond to three conditions of the information coverage of crop distribution (low, median, and high) (Table S1, Fig. S1). Updating annual crop-specific area maps is important especially for regions like Africa and China, where operational annual crop mapping and monitoring is not available and is largely limited by time-consuming sample collecting process and laborious field work. In our framework, we collected related spatial indicator used in previous studies and trained machine learning models to predict spatiotemporal dynamics of crop-specific areas based on them. Annual crop statistics were further disaggregated based on the probabilistic layer and harmonized based on multiple constraints. Finally, we produced maps of crop-specific areas covering 42 types from 1961–2022 in Africa, maps of crop-specific areas covering 14 types from 1980–2022 in China and maps of crop-specific areas covering 15 types from 2008–2022 in USA (only for validation).

Methods

In this study, three regions were selected as study areas, respectively Africa, China, and USA. They correspond to three conditions of the information coverage of crop distribution (low, median, and high). In Africa, there are only crop statistics provided in most areas. While in China, except for statistics, there have been many studies producing single-type crop maps in recent years but not integrated multi-type maps. But in USA, Crop Data Layer product (CDL) provides annual-update crop maps covering the whole crop categories. Therefore, we respectively collected crop statistics and base maps for these regions. In addition, we also prepared cropland extent datasets and spatial indicators related with crop distribution for further spatiotemporal modeling.

Data Preparation

Crop statistics

Firstly, we collected different sources of crop statistics in different study regions (Table 1), which provide the total amount of crop-specific areas. FAOSTAT, the biggest dataset in the field of food and agriculture, provides free access to food and agriculture data for over 245 countries and territories from 1961 to the most recent year available (https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data). Here, Crops and livestock products datasets in FAOSTAT’s Production domain were collected, which contained information on harvested area of more than 143 crop types. According to the categories of SPAM products, it is integrated into 42 crop categories through FAO code (Table S2–1).

In countries with large land area such as USA and China, national statistics are insufficient to capture the details of spatial changes. Therefore, we collected statistics at a sub-national level from national official reports in these two counties. As for USA, National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) from United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) provides access to census or survey of crop harvested area at the state level (https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/). In China, statistics of crop-specific areas were acquired from China’s economic and social big data research platform operated by China National Knowledge Infrastructure. Due to the differences in crop categories from multiple sources, we matched 15 and 14 crop types respectively in USA and China according to the categories of SPAM products (Table S2–2, Table S2–3).

In addition, it is also a vital step to relate statistics to georeferenced locations. The Global Administrative Unit Layers (GAUL), one of the most standard spatial datasets of administrative units, compiles and disseminates the best available information on different levels of administrative units for countries in the world. Here, we used GAUL at national levels (ADM0) and sub-national levels (ADM1) to form geo-referenced crop harvest datasets respectively in Africa and USA/China (Table 1).

Base maps

Compared to statistics which represent total amount, base maps provide a detailed portrayal of crop-specific areas, which will be essential for spatiotemporal dynamic modeling. There are multiple maps of crop-specific areas with global coverage and detailed categories. And among which SPAM2010 product were chosen in this study for its sophisticated approaches and latest updates, providing key information about the distribution of crop-specific areas in regions in which remote sensing techniques have not been used widely in crop mapping such as Africa (Table 2).

However, more accurate and timely crop distribution information in countries like USA can be acquired by higher spatial resolution maps produced by remote sensing and field survey. Therefore, we adopted Crop Data Layer (CDL) as the base map in USA (Table 2). The correspondence between CDL’s crop categories and SPAM is presented in the Supplement (Table S2–2). As for China, there is still not an integrated multi-type crop map with medium-high spatial resolutions (10–30 m). Therefore, we collected multi-source base maps of 8 crop types to produce more accurate and timely references (Table S3–1), as for the rest crop types and the regions that are not covered, we still used SPAM2010 as the base map. To ensure uniform resolution, we calculate the proportion of the crop area within a 10 km (~5 arcmin) grid for the base map with higher resolution (10m-30m).

Cropland extent

Cropland extent determines where statistics of crop-specific areas can be allocated. In order to provide an annual-updated basis to track spatiotemporal dynamics, we integrated two datasets to produce annual cropland extent from history to the most recent year. It is an efficient and accurate way to identify cropland from classified land cover products. FROM-GLC Plus provides a framework for near real-time land cover mapping at multi-temporal (annual to daily) and multi-resolution (30 m to sub-meter) levels43. Here, we used FROM-GLC Plus Global Land Cover Products (1982–2021, 1 km subpixel) to extract cropland extent from 1982 to 2021. In periods where there were rarely remotely sensed images (before the 1980s), GCD (Global Cropland Dataset), a collection of historical cropland maps generated by spatially allocating cropland statistics, was used as extent44 (Table S3-5). Given that crop production may take place over several seasons within a year, we also multiplied the cropland extent by the cropping intensity to get the annual maximum harvested area. Annual cropping intensity datasets cover periods from 2001 to 201945. For the remaining years, data from the nearest year is used as a substitute (Table S3-6). To ensure uniform resolution, we resampled the cropland extent and maximum harvested area of all year periods to 10 km (~5 arcmins).

Spatial indicators

To better model spatiotemporal dynamic of crop-specific areas, a total of 26 related spatial indicators were collected from 7 aspects, including climate, agro-system, suitability, potential yield, soil, terrain, and location (Table S3-10). These indicators are proved to be related to the distribution of crop-specific areas in previous studies. To ensure uniform resolution, we resampled the spatial resolution of all spatial indicators to 10 km (~5 arcmin).

Climate determines the areas in which crops are suitable for cultivation, and climate change affects the potential yields and revenue, thus affecting farmer decisions. It is reported that climatic variables explain considerable portions of the variance in crop planted area (22–30%), harvestable fraction (15–28%) and yield (32–50%)46. In this study, five climate variables were calculated from ERA5-Land including annual mean temperature (temp), total annual precipitation (prec), downwards surface solar radiation (radi_down), evaporation from vegetation transpiration (evap_veg) and growing degree day (gdd) (Table S3-10). We present a detailed description of these variables in the Supplement (Sect. S3-2).

In addition, terrain and soil properties are also essential variables of crop suitability. However, these variables are only available at single time period unlike climate variables that updated annually. More specifically, slope and elevation in the year 2010 were calculated from GMTED2010 as the terrain variables while aggregation of soil water content, PH, texture class, organic carbon content, sand content and clay content at different depths were calculated from OpenlandMap datasets as soil variables. We present a detailed description of terrain and soil variables in the Supplement (respectively Sect. S3-3 and Sect. S3-4).

We also selected the suitability assessment result of each crop as input for this prediction model. GAEZv4.0 produces a gridded suitability assessment for 48 major crops in two input levels (i.e., high, low), and two water supply regimes (i.e., irrigated or rainfed) at 5 arcmin resolution. The correspondence between GAEZ v4.0’s crop categories and SPAM is presented in the Supplement (Table S2-4). Most of the SPAM2010 crops are included in GAEZ’s crop categories, those not included are assigned values from similar crops. Potential yield has a greater impact on farmer decisions when multiple crops are suitable to cultivate, this variable could also be accessed by GAEZv4.0 product in two input levels and two water supply regimes. The suitability index and potential yield in three regimes (irrigated, rainfed and high input, rainfed and low input) were selected as input indicators. We present a detailed description of suitability and potential yield variables’ processing progress in the Supplement (respectively Sect. S3-5 and Sect. S3-6).

Agro-system variables are directly related to crop distribution. Firstly, cropland maps determine where and to which extent crop could be cultivated (also mentioned above). Furthermore, crop cultivation suitability and potential yield vary greatly in irrigation or rainfed regimes. Therefore, we integrated two datasets (HID and SPAM) to extract irrigation area proportion in a long time series. HID (historical irrigation data set) provides estimates of the temporal development of the area equipped for irrigation since 1900 at 5 arcmin resolution47, while SPAM contains irrigation area proportion information in year 2000, 2005 and 2010. What’s more, it is said that the proportions of crops being distributed on farms of different sizes vary greatly48. So we select a global field size map as an indicator which classifies farm size into 5 classes49. Last but not least, rural population is closely related to agricultural production, which can be considered as a measure of agricultural labor and also market accessibility. Estimates of rural population from HYDE (History Database of the Global Environment) were selected as the last indicator of the agro-system group50. We present a detailed description of agro-system variables’ processing progress in the Supplement (respectively Sect. S3-7, S3-8, S3-9, S3-10).

Workflow design

There are mainly two steps in annually updating spatiotemporal dynamics of crop-specific areas. The first step is to generate probabilistic spatiotemporal dynamics layers through machine learning based on spatial indicators and base maps, while the latter step is to allocate crop statistics based on the probabilistic layer and harmonize the result based on multiple constraints (Fig. 1).

Generating probabilistic spatiotemporal dynamics

In this part, we trained machine learning models for each crop in each region based on spatial indicators and base maps. To begin with, we collected samples on the base map using a stratified random strategy. The sample set of each crop is set to collect a maximum of 10000 points at the resolution of 10 km. We only collected samples at the pixel where crop-specific area exists. Combined with spatial indicators mentioned above, we chose random forest (RF) regression model to learn the rules by which crop distribution is affected by 26 spatial indicators from sample sets. RF has been proven to be effective and efficient in dealing with multi-dimensional features51 and RF regression has been widely used in tasks of predicting the distribution of geospatial targets such as population, cropland, etc.44,52. More specifically, we use the random forest algorithm in Google Earth Engine to build the regression model. According to the results of sensitivity analysis, the number of decision trees is set to 100 (more details can be found in Supplement Information), and the number of features required for each node for splitting is set to the square root of the number of input features set by default.

Statistic allocation and harmonization

In this part, crop statistics were allocated based on probabilistic layers predicted by the RF regression model and harmonized according to multiple constraints. More specifically, we first calculate the sum of probabilistic values at the administrative unit level (excluding areas with no cropland or suitability index of 0). The sum value was used to compare with crop statistics at the same administrative unit and the rate was used to adjust probabilistic layers at this administrative unit (Eq. (1)). The descriptions of variables in the equations are listed in Table 3 (the same below).

Then, we defined the maximum crop harvested area in each grid as the limit that no more crop statistics could be allocated (Eq. (2)). More specifically, the maximum crop harvested area is calculated by multiplying cropland and crop intensity (more data sources descriptions in Data Preparation Section).

Further, we used \({{\rm{HarvAreaL}}{\rm{eft}}}_{{iy}}\) to represent the conflict between the maximum crop harvested area and statistics allocation of all crops in total (Eq. (3)). In order to compare in the same unit, we transformed the adjusted proportion of crop-specific areas from proportion (0-1) into area (ha) by multiplying \({{PixelArea}}_{i}\).

Statistic allocation was performed in a crop-by-crop order which is specified in each administrative unit. We classified the crop type list into several types: annual or perennial, specific name (e.g. wheat) or general name (e.g. other cereals). The priority of perennial crops is higher than annual ones, and then crops with specific name will be processed first compared with that of general names. We further ranked the crop type list in each sub-group according to the crop area statistics in the administrative unit in descending order. To reduce errors due to inconsistent definitions of cropland, permanent crops were excluded from the cropland extent constraints (See more details in Supplement Information S2 Crop categories). It’s worth noting that when maximum crop harvested area is achieved in a certain grid \({\rm{i}}\), the statistic of the crop type \({\rm{j}}\) being processed would not be allocated. The crop type \({\rm{j}}\) and crop types behind \({\rm{j}}\) in the ranked crop list would be saved in a grid-specific list \({{LeftCrop}}_{{iy}}\). We further summed the statistics still not be allocated yet (\({{\rm{StatLeft}}}_{{jky}}\)) in a grid where maximum of crop harvested area is achieved based on \({{LeftCrop}}_{{iy}}\) (Eq. (4)).

We adopted two strategies to deal with statistics still not being allocated yet (\({{\rm{StatLeft}}}_{{jky}}\)). The first one is to allocate crop statistics to the grids where the maximum crop harvested area is not achieved according to the probability value predicted by the RF model (Eq. (5)). If there are statistics still not allocated yet, the latter process will allocate crop statistics to the grids where the maximum crop harvested area is not achieved according to the rest space of crop harvested area (Eq. (6)).

At last, we got the adjusted proportions of crop-specific areas (after Eqs. (5) or (6)), and the final result \({{\rm{CropArea}}}_{{ijy}}\) represents the harvested area (ha) of crop type \({\rm{j}}\) in grid \({\rm{i}}\) in year \({\rm{y}}\) (Eq. (7)).

Data Records

Datasets produced by this study are available to the public at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26028769, which include annual maps of crop-specific areas covering 42 types from 1961–2022 in Africa, annual maps of crop-specific areas covering 14 types from 1980–2022 in China and annual maps of crop-specific areas covering 15 types from 2008–2022 in USA (only for validation)53. Data files are named according to the format ‘[Region]_[year].tif’, each data file has a certain number of bands which correspond to the crop types and respectively named as the short names of crop types (refer to Supplementary Table S2-1, S2-2, S2-3 for the whole crop categories). Datasets are provided in a Geotiff format and in ESPG: 4326 (GCS_WGS_1984) spatial reference system at the spatial resolution of 10 km. Crop-specifics areas are measured in hectares. The datasets will be continuously maintained, updated, and further developed.

Here, we presented our mapping results of crop-specific areas in China (Fig. 2) and Africa (Fig. 3) in multiple time stages by selecting the representative crops for each category. It can be seen that our results can characterize the distribution of crop-specific areas over long periods of time.

Technical Validation

Crop-specific area maps produced in this study are estimates of crop harvested area distribution with various uncertainties. Therefore, we adopted multiple methods to validate the effectiveness of our method and the accuracy of our products. First of all, we selected independent crop maps which are not used in our mapping process to verify our products. In the part of data comparison, we calculated two accuracy indicators as a representation of consistency. The first one is the coefficient of determination (R2) between the values of our products and others. A higher R2 generally indicates a better performance. The second one is the root-mean-square-error (RMSE) between the values of our products and others. In contrast, a lower RMSE generally indicates a better consistency of two datasets.

SPAM2010 was used as base map in the process of our product especially in Africa. However, the SPAM model also produces global maps of crop harvested area in 2000, 2005 and 2020. The SPAM200554 and SPAM202055 was selected to validate our products for crop categories of SPAM2000 is not same as the other two, covering 20 crops rather than 42 crops. Besides for validation, the other reason why SPAM products in other years was not used as the input in our model is that it is not recommended to cross-compare SPAM products over time for differences may contain more errors or inaccuracies than real changes in the ground20.

Results show that crop map in 2005 and 2020 updated by our method has a relatively good consistency with SPAM2005 and SPAM2020 at the 10 km grid level in Africa (Figs. 4, 5). Maize, cassava, groundnut, cowpea are the representative crops of cereals, roots & tubes, oil crops and pulses with the largest harvested area in each group in Africa. In the year 2005, the values of R2 are between 0.42 and 0.74, the values of RMSE are between 160 and 365 ha among these crops, and the values of R2 are between 0.29 and 0.65, the values of RMSE are between 458 and 749 ha in the year 2020. We admit that there are crop types with a relatively low value of R2, while these crop types are mainly crop aggregates (e.g. other fibers, rest crops) (Table S4–1).

Comparison between our results (2005) and SPAM2005 in Africa at the 10 km grid level. A total of 15 crops with the large planting area in Africa were selected, including (a) barley; (b) bean; (c) cassava; (d) cocoa; (e) cotton; (f) cowpea; (g) groundnut; (h) maize; (i) oil palm; (j) pearl millet; (k) rice; (l) small millet; (m) sorghum; (n) vegetables; (o) wheat. Comparison results of other crops could be found in Table S4–1.

Comparison between our results (2020) and SPAM2020 in Africa at the 10 km grid level. A total of 14 crops with the large planting area in Africa were selected, including (a) barley; (b) bean; (c) cassava; (d) cocoa; (e) cotton; (f) cowpea; (g) groundnut; (h) maize; (i) oil palm; (j) pearl millet; (k) rice; (l) sorghum; (m) vegetables; (n) wheat. Comparison results of other crops could be found in Table S4–2. Small millet is not included in SPAM2020 and was therefore excluded (compared with Fig. 4).

As for China, we used integrated multi-source crop distribution maps as base map (not only SPAM2010), which will introduce uncertainty and also greater differences at the grid scale compared with the SPAM series products. Therefore, we aggregated the result of SPAM2005 and SPAM2020 at adm2 level to compare with ours at the same unit for SPAM series product collected as many adm2 level statistics data as possible, among which the adm2 level statistics coverage rate in SPAM2005 accounts for 54.6% (global average). Results show that crop map in 2005 updated by our method has a relatively good consistency with SPAM2005 at the adm2 level in China (Fig. 6), especially maize (R2 = 0.86), soybean (R2 = 0.73), tobacco (R2 = 0.84), vegetables (R2 = 0.68) and wheat (R2 = 0.90). And our product also has a good consistency with SPAM2020 among these crops (Fig. 7), especially maize (R2 = 0.87), soybean (R2 = 0.64), tobacco (R2 = 0.70), vegetables (R2 = 0.67) and wheat (R2 = 0.89), which provides additional evidence, to some extent, for the temporal robustness of our approach. We noticed that there are some crops that have a poor consistency such as roots, bast fiber, sugarbeet, sugarcane (Fig. S4–1, Fig. S4–2). It is caused by inconsistency of statistics from adm1 and adm2 for there is a missing value collected at the adm2 level (from SPAM product) but the result collected at adm1 unit has a nonzero statistic value.

Comparison between our results (2005) and SPAM2005 in China at the Administrative unit (adm2 level), excluding crop types with strong inconsistency of statistics from adm1 and adm2, which includes (a) cotton; (b) groundnut; (c) maize; (d) rapeseed; (e) rice; (f) soybean; (g) tobacco; (h) vegetables; (i) wheat. Full comparison results could be found in Fig. S4–1.

Comparison between our results (2020) and SPAM2020 in China at the Administrative unit (adm2 level), excluding crop types with strong inconsistency of statistics from adm1 and adm2, which includes (a) cotton; (b) groundnut; (c) maize; (d) rapeseed; (e) rice; (f) soybean; (g) tobacco; (h) vegetables; (i) wheat. Full comparison results could be found in Fig. S4–2.

To verify the products’ accuracy in a time series, we compared our products with PCAM (Probabilistic Cropland Allocation Model). PCAM is produced based on randomly allocating statistics to the probability cluster of crop suitability through multiple Monte Carlo, which provides the crop-specific area harvested of 17 major crops in a global 0.5-degree grid from 1961 to 201437,56. Other datasets such as M3, MIRCA, GAEZ, and SPAM only provide maps at certain years. We resampled the spatial resolution PCAM to 10 km before comparison. Results showed that our products do not have a good consistency with PCAM, with relatively high RMSE (some crop types exceed 1000 ha) and low R2 (mainly between 0.2 to 0.4) (Fig. S4–3). This may relate to the reason that PCAM has a coarser spatial resolution, where crop-specific areas distributed in our product are not covered by PCAM (Fig. S4–4).

Besides, we also carried out contrast experiments to verify the role of key parts of our model. Producing annual-updated probabilistic layers is one of the essential parts of this study, which were used as the basis of crop statistics allocation at certain years. Here, we conducted experiments to prove the effectiveness of this step. More specifically, we compared the accuracy differences between results produced by annual-updated probabilistic layers and only base-year layers (SPAM2010), other experiment settings (including method and input data) are the same. Results showed that the input of annual-updated probabilistic layers significantly improved mapping accuracy in almost every crop type, with higher R2 and lower RMSE (Fig. 8). For example, compared with SPAM2005, R2 of maize maps produced with updated probabilistic layers in 2005 is 0.487, which is higher than using only the base map (0.151), while RMSE is 360 ha, lower than using only the base map (524 ha). We acknowledge that the model is trained using spatial indicators and crop distribution data from a single base year and then applied to subsequent years. However, the results indicate that generating annually updated probabilistic layers using Random Forest is an effective approach for temporal transfer. When multi-year base maps are available (as demonstrated in the case of China in this study), incorporating such data is recommended to further improve the model’s ability to transfer across years. See more details about model interpretability in Supplement Information Section 5-2 Model uncertainty.

In addition, we tested the whole model by transferring it into regions with rich data. USA, one of the regions with the most sufficient and accessible crop area references in the world, is selected as one of the study areas to conduct the same work flow to validate the effectiveness and feasibility, especially updating crop-specific area maps in annual series. Here, we selected CDL in the year 2010 as the base map (the same setting in Africa, using SPAM2010) and updated annual probabilistic layers based on the RF regression model trained based on CDL 201044. Final results were produced by allocating crop statistics from USDA based on annually updated layers. Results showed that our method could generate annual crop maps with relatively consistent accuracy (Fig. 9). As for staple crop types such as maize, soybean and wheat, annually updated crop maps achieved relatively higher R2 (between 0.53 to 0.78) and lower RMSE (between 492 to 727 ha) with less variation in time series, while we also noticed that mapping accuracy of some crops fluctuates greatly in a given year, especially crops of small harvested areas such as tobacco, sugarcane and groundnut in terms of RMSE. As for R2, almost all of the rest crops except for staple ones have some fluctuation (Fig. 9).

Last but not least, we compared the crop statistics and the aggregation result of crop-specific area maps at the same administrative units to verify the effectiveness of this allocation process. Results show that our method allocated almost all crop statistics into crop-specific areas at the corresponding administrative unit with R2 over 0.8 and a slope close to 1 (Fig. 10). The reason why crop statistic and mapping results are not completely consistent at the administrative unit level is that the pixels at the edge of the administrative boundary have not been uniformly processed. In addition, when the statistical data is too large, some of the data cannot be reasonably allocated to cropland and suitable land for specific crops, and these pixel values are replaced by the base map.

Usage Notes

Our products provide approximate estimates for spatiotemporal dynamics of crop-specific areas in multiple regions (especially for Africa and China) over several decades, which could be used as data basis for food security and environmental impact assessments. Datasets are provided in a Geotiff format, and thus can be easily read and processed by GIS software (e.g. QGIS, ArcGIS etc.) and other coding languages (e.g. Python etc.). In this dataset, crop type name follows the naming system used by SPAM product crop categories and crop-specifics areas are measured in hectares. Our estimates of crop-specific areas are largely dependent on the quality of input data (both crop statistics and input spatial data), which should be regarded more as approximate estimates rather than ground realities. The total harvested area in this dataset may not fully align with agricultural census data. Users should interpret these values with caution and may optionally scale the data according to official statistics for specific applications.

Code availability

Workflows to update spatiotemporal dynamics of crop-specific areas (in Method section) were implemented in Python and workflows to conduct validation (in Technical Validation section) were implemented in Python and R. The source code is publicly available at: https://github.com/lixiyu21/Crop_Statistic_To_Map.

References

Ellis, E. C. et al. Used planet: A global history. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, 7978–7985, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1217241110 (2013).

Monfreda, C., Ramankutty, N. & Foley, J. A. Farming the planet: 2. Geographic distribution of crop areas, yields, physiological types, and net primary production in the year 2000. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 22, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GB002947 (2008).

Siebert, S. & Döll, P. Quantifying blue and green virtual water contents in global crop production as well as potential production losses without irrigation. Journal of Hydrology 384, 198–217, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.07.031 (2010).

You, L. & Sun, Z. Mapping global cropping system: Challenges, opportunities, and future perspectives. Crop and Environment 1, 68–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crope.2022.03.006 (2022).

Davis, K. F. et al. Meeting future food demand with current agricultural resources. Global Environmental Change 39, 125–132, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.05.004 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Dietary Transition Determining the Tradeoff Between Global Food Security and Sustainable Development Goals Varied in Regions. Earth’s Future 10, e2021EF002354, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EF002354 (2022).

Song, X.-P. et al. Massive soybean expansion in South America since 2000 and implications for conservation. Nature Sustainability 4, 784–792, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00729-z (2021).

Zhang, G. et al. Fingerprint of rice paddies in spatial–temporal dynamics of atmospheric methane concentration in monsoon Asia. Nature Communications 11, 554, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-14155-5 (2020).

Hoang, N. T. et al. Mapping potential conflicts between global agriculture and terrestrial conservation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120, e2208376120, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2208376120 (2023).

Vogel, E. et al. The effects of climate extremes on global agricultural yields. Environmental Research Letters 14, 054010, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab154b (2019).

Laborde, D., Martin, W., Swinnen, J. & Vos, R. COVID-19 risks to global food security. Science 369, 500–502, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc4765 (2020).

Lin, F. et al. The impact of Russia-Ukraine conflict on global food security. Global Food Security 36, 100661, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2022.100661 (2023).

Bren d’Amour, C. et al. Future urban land expansion and implications for global croplands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 8939–8944, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606036114 (2017).

Huang, Q. et al. The occupation of cropland by global urban expansion from 1992 to 2016 and its implications. Environmental Research Letters 15, 084037, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab858c (2020).

Hu, Q. et al. Integrating coarse-resolution images and agricultural statistics to generate sub-pixel crop type maps and reconciled area estimates. Remote Sensing of Environment 258, 112365, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2021.112365 (2021).

Lu, M. et al. A cultivated planet in 2010 – Part 1: The global synergy cropland map. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 1913–1928, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-1913-2020 (2020).

Potapov, P. et al. Global maps of cropland extent and change show accelerated cropland expansion in the twenty-first century. Nature Food 3, 19–28, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00429-z (2022).

Ramankutty, N., Evan, A. T., Monfreda, C. & Foley, J. A. Farming the planet: 1. Geographic distribution of global agricultural lands in the year 2000. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 22, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GB002952 (2008).

You, L., Wood, S., Wood-Sichra, U. & Wu, W. Generating global crop distribution maps: From census to grid. Agricultural Systems 127, 53–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2014.01.002 (2014).

Yu, Q. et al. A cultivated planet in 2010 – Part 2: The global gridded agricultural-production maps. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 3545–3572, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-3545-2020 (2020).

Nelson, G. et al. Income growth and climate change effects on global nutrition security to mid-century. Nature Sustainability 1, 773–781, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0192-z (2018).

Boryan, C., Yang, Z., Mueller, R. & Craig, M. Monitoring US agriculture: the US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, Cropland Data Layer Program. Geocarto International 26, 341–358, https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2011.562309 (2011).

d’Andrimont, R. et al. From parcel to continental scale – A first European crop type map based on Sentinel-1 and LUCAS Copernicus in-situ observations. Remote Sensing of Environment 266, 112708, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2021.112708 (2021).

Alami Machichi, M. et al. Crop mapping using supervised machine learning and deep learning: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Remote Sensing 44, 2717–2753, https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2023.2205984 (2023).

Leff, B., Ramankutty, N. & Foley, J. A. Geographic distribution of major crops across the world. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 18, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GB002108 (2004).

Portmann, F. T., Siebert, S. & Döll, P. MIRCA2000—Global monthly irrigated and rainfed crop areas around the year 2000: A new high-resolution data set for agricultural and hydrological modeling. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 24, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GB003435 (2010).

Fischer, G. et al. Global agro-ecological zones v4–model documentation. (Food & Agriculture Org., 2021).

You, L. & Wood, S. An entropy approach to spatial disaggregation of agricultural production. Agricultural Systems 90, 329–347, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2006.01.008 (2006).

You, L., Wood, S. & Wood-Sichra, U. Generating plausible crop distribution maps for Sub-Saharan Africa using a spatially disaggregated data fusion and optimization approach. Agricultural Systems 99, 126–140, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2008.11.003 (2009).

Anderson, W., You, L., Wood, S., Wood-Sichra, U. & Wu, W. An analysis of methodological and spatial differences in global cropping systems models and maps. Global Ecology and Biogeography 24, 180–191, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12243 (2015).

Becker-Reshef, I. et al. Crop Type Maps for Operational Global Agricultural Monitoring. Scientific Data 10, 172, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02047-9 (2023).

Tang, F. H. M. et al. CROPGRIDS: a global geo-referenced dataset of 173 crops. Scientific Data 11, 413, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03247-7 (2024).

Grogan, D., Frolking, S., Wisser, D., Prusevich, A. & Glidden, S. Global gridded crop harvested area, production, yield, and monthly physical area data circa 2015. Scientific Data 9, 15, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-01115-2 (2022).

Kebede, E. A. et al. A global open-source dataset of monthly irrigated and rainfed cropped areas (MIRCA-OS) for the 21st century. Scientific Data 12, 208, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04313-w (2025).

Ray, D. K., Ramankutty, N., Mueller, N. D., West, P. C. & Foley, J. A. Recent patterns of crop yield growth and stagnation. Nature Communications 3, 1293, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2296 (2012).

Davis, K. F. et al. HarvestStat: a global effort towards open and standardized sub-national agricultural data. Environmental Research Letters 20, 052001, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/adcb54 (2025).

Jackson, N. D., Konar, M., Debaere, P. & Estes, L. Probabilistic global maps of crop-specific areas from 1961 to 2014. Environmental Research Letters 14, 094023, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab3b93 (2019).

Zabel, F., Knüttel, M. & Poschlod, B. CropSuite v1.0 – a comprehensive open-source crop suitability model considering climate variability for climate impact assessment. Geosci. Model Dev. 18, 1067–1087, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-18-1067-2025 (2025).

Chemura, A., Gleixner, S. & Gornott, C. Dataset of the suitability of major food crops in Africa under climate change. Scientific Data 11, 294, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03118-1 (2024).

Pei, J. et al. Downscaling Administrative-Level Crop Yield Statistics to 1 km Grids Using Multisource Remote Sensing Data and Ensemble Machine Learning. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 17, 14437–14453, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2024.3441252 (2024).

Luo, Y. et al. Accurately mapping global wheat production system using deep learning algorithms. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 110, 102823, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2022.102823 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Luo, Y., Han, J., Xu, J. & Tao, F. Estimating Global Wheat Yields at 4 km Resolution during 1982–2020 by a Spatiotemporal Transferable Method. Remote Sensing 16 (2024).

Yu, L. et al. FROM-GLC Plus: toward near real-time and multi-resolution land cover mapping. GIScience & Remote Sensing 59, 1026–1047, https://doi.org/10.1080/15481603.2022.2096184 (2022).

Cao, B. et al. A 1km global cropland dataset from 10000BCE to 2100CE. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 5403–5421, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-5403-2021 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Annual dynamic dataset of global cropping intensity from 2001 to 2019. Scientific Data 8, 283, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-01065-9 (2021).

Wei, D., Gephart, J. A., Iizumi, T., Ramankutty, N. & Davis, K. F. Key role of planted and harvested area fluctuations in US crop production shocks. Nature Sustainability 6, 1177–1185, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01152-2 (2023).

Siebert, S. et al. A global data set of the extent of irrigated land from 1900 to 2005. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 1521–1545, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-19-1521-2015 (2015).

Su, H., Willaarts, B., Luna-Gonzalez, D., Krol, M. S. & Hogeboom, R. J. Gridded 5 arcmin datasets for simultaneously farm-size-specific and crop-specific harvested areas in 56 countries. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 4397–4418, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-4397-2022 (2022).

Lesiv, M. et al. Estimating the global distribution of field size using crowdsourcing. Global Change Biology 25, 174–186, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14492 (2019).

Klein Goldewijk, K., Beusen, A., Doelman, J. & Stehfest, E. Anthropogenic land use estimates for the Holocene–HYDE 3.2. Earth System Science Data 9, 927–953 (2017).

Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 45, 5–32, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Sorichetta, A. et al. High-resolution gridded population datasets for Latin America and the Caribbean in 2010, 2015, and 2020. Scientific Data 2, 150045, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2015.45 (2015).

Li, X., Yu, L., Du, Z., Liu, X. & You, L. Crop Statistic to Annual Map: Tracking spatiotemporal dynamics of crop-specific areas through machine learning and statistics disaggregating. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26028769.v2 (2025).

International Food Policy Research, I. & International Institute for Applied Systems, A. Global Spatially-Disaggregated Crop Production Statistics Data for 2005 Version 3.2, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DHXBJX (2016).

International Food Policy Research, I. Global Spatially-Disaggregated Crop Production Statistics Data for 2020 Version 1.0, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SWPENT (2024).

Jackson, N. D., Konar, M., Debaere, P. & Estes, L. Data for: Probabilistic global maps of crop-specific areas from 1961 to 2014 https://doi.org/10.13012/B2IDB-7439710_V1 (2019).

International Food Policy Research, I. Global Spatially-Disaggregated Crop Production Statistics Data for 2010 Version 2.0, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PRFF8V (2019).

USDA-NASS. (ed USDA-NASS) (Washington, DC, 2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFE0209400) and the open project of State Key Laboratory of Efficient Utilization of Arable Land in China, the Institute of Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (No. EUAL-2025-03). The authors acknowledge the support of Dr. Liangzhi You from the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. and Y.L. designed the framework and X.L. developed the datasets. X.L. prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Yu, L., Du, Z. et al. Crop Statistic to Annual Map: Tracking spatiotemporal dynamics of crop-specific areas through machine learning and statistics disaggregating. Sci Data 12, 1249 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05572-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05572-x