Abstract

Sepsis is a severe disease and induces skeletal muscle atrophy, which has a significant impact on patients. Moreover, the onset and severity of muscle atrophy can vary across different anatomical regions during sepsis. Our previous study demonstrated that ZBED6 knockout not only promotes skeletal muscle growth under physiological conditions, but also alleviates systemic muscle atrophy during sepsis. However, its region-specific effects on sepsis-induced muscle atrophy have not been analyzed. In this study, we performed RNA sequencing for 54 samples of skeletal muscle from nine different anatomical regions from male ZBED6 knockout and wild-type (WT) minipigs subjected to sepsis. We generated 364.63 Gb of high-quality bulk RNA sequencing data from the skeletal muscle samples (approximately 6.75 Gb per sample). This dataset provided insightful gene expression information to understand the role of ZBED6 in region-specific muscle atrophy during sepsis. In addition, this dataset can be used for heterogeneity analysis between skeletal muscle tissues from multiple species or female pigs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Sepsis can lead to dysfunction in multiple organ systems1,2 and induces skeletal muscle atrophy3. There has been increasing recognition that muscle atrophy and muscle weakness associated with sepsis are important issues in sepsis survivors4. The largest and most widely used rodent models have limited the progress of medical research due to their distant affinities with humans and the large differences in genetic background, body size and lifespan from humans5. Pigs are increasingly being used for translational research and the development of transgenic models6 due to their genetic background7, body size, physiology and anatomy8 that are more similar to humans. Previous studies have shown that ZBED6 is widely distributed in multiple tissues and that it regulates placental mammalian skeletal muscle growth9. In mice and pigs, knockdown of ZBED6 accelerated growth and increased skeletal muscle weight10.

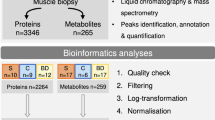

To characterize the gene expression differences in muscle physiological activities in sepsis model pigs after ZBED6 knockout, we constructed RNA-seq libraries and performed paired-end 150 bp sequencing of 54 skeletal muscle tissue samples from nine different anatomical regions in ZBED6 knockout and control pigs (Fig. 1). A total of six samples from each region were divided into two groups (three for ZBED6 knockout group and three for control group).

The total mapping rate of all samples was greater than 95% (Fig. 2a). The clustering pattern of muscle expression at different regions showed variations in the anterior, middle and posterior trunks, except for tibialis anterior (TA) (Fig. 2b). And the ZBED6 knockout samples and control samples of each anatomical region showed significant separation (Fig. 2c).

Transcriptome data description of septic pig muscles. (a) Mapping rates of all samples relative to the Sscrofa11.1 reference genome. (b) t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) analysis based on gene TPM values of all samples from 9 different sampling locations. TIP: Triceps brachii, BIP: Biceps brachii, RA: Rectus abdominis, LD: Longissimus dorsi muscle, PMM: Psoas major muscle, GAS: Gastrocnemius, TA: Tibialis anterior, EDL: Extensor digitorum lateralis, SOL: Soleus. (c) t-SNE analysis based on gene TPM values of control and ZBED6 gene knockout samples at each sampling location.

In order to explore the gene expression characteristics of muscles in different regions, the spearman correlation coefficients of control group samples from each region were calculated, and in general the samples from the same sampling region showed relatively higher correlation (Fig. 3a). The calculation of genes specifically expressed in each muscle region showed different numbers: BIP (3), RA (107), LD (7), PMM (4), SOL (33), GAS (3), EDL (9) and TA (9)11 (Fig. 3b). And GO terms such as ‘immunoglobulin production’, ‘antigen binding’, ‘regulation of calcium-mediated signaling’, ‘positive regulation of cytosolic calcium ion concentration’ and other were significantly enriched by RA-specific genes. GO terms such as ‘monoatomic ion transmembrane transporter activity’, ‘chloride channel activity’ and other were significantly enriched by SOL-specific genes (Fig. 3c).

Genes specifically expressed in different locations muscles. (a) Spearman correlation of control group samples from nine locations. (b) The expression heatmap of specific genes (τ value ≥ 0.75) from nine locations. (c) The significant (P values < 0.01) results of functional enrichment analysis of genes specifically expressed in RA, SOL or EDL.

Differential expression analysis of genes showed inconsistencies in the number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the ZBED6 knockout and control groups in each region (Fig. 4a). And four shared up-regulated differential genes were found in all regions (Fig. 4b), but no shared down-regulated differential genes (Fig. 4c).

Gene differential expression analysis and muscle fiber type assessment. (a) The numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in muscle tissues from different sampling locations between KO and WT groups. (b) The intersections of upregulated DEGs in different regions. (c) The intersections of downregulated DEGs in different regions. The panel on the left represents the sum of the number of genes unique to each sampling location and shared by all locations. The bar plot on the right panel represents the number of each set, and the dot plot indicates the sets. (d) Prediction of the proportion of three types of muscle fibers in each muscle tissue.

Estimation of the myofiber content of the samples showed that none of the ZBED6 knockout sepsis group compared to the control group differed significantly, although type I, IIA, and IIB myofibers differed in different anatomical regions (Fig. 4d).

Methods

Ethics statement

All experimental procedures with pigs were performed according to the Guidelines for Experimental Animals established by the Ministry of Science and Technology (Beijing, China, revised in March 2017). Ethical approval on animal survival was given by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Northwest A & F University (approval number: NWAFU-314020808). The experiments were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Animals and sample collection

Animal experiments were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Northwest A&F University. Bama miniature pigs were bred and housed at the Laboratory Animal Center of Chengdu Clonorgan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., with ad libitum access to food and water unless otherwise specified. Male offspring were genotyped and randomly assigned to experimental groups at 9 months of age, with littermate controls used throughout. To ensure objectivity, all experiments were performed by investigators blinded to group allocations. A porcine model of sepsis was established in six adult male minipigs (9 months old), including three wild-type (WT) and three ZBED6-deficient animals. Sepsis was induced using a modified cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) procedure, as previously described12. Briefly, under general anesthesia, peritonitis was induced via CLP, followed by fluid resuscitation. After surgery, the animals were housed individually with continuous access to food. On day 14 post-CLP, skeletal muscle samples were collected from nine anatomical regions: triceps brachii (TIP), biceps brachii (BIP), rectus abdominis (RA), longissimus dorsi (LD), psoas major (PMM), gastrocnemius (GAS), tibialis anterior (TA), extensor digitorum lateralis (EDL), and soleus (SOL). Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA sequencing analysis.

RNA-Seq library construction and sequencing

Muscle tissue sample was homogenized in a tissue grinder for total RNA extraction using TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA) extraction method. The purity of the total RNA was estimated using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The integrity and concentration of total RNA was assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). 54 rRNA-depleted and random priming RNA-seq libraries were constructed. And then these libraries were sequenced using MGI DNBSEQ platform with a paired-end sequencing length of 150 bp (PE 150) by Annoroad Gene Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). The SRA accession number for this dataset is SRP53950713.

Gene expression analysis

Low-quality reads were removed and the Q20 and Q30 values and the GC content were calculated for the clean reads. Clean data were mapped to the pig reference genome (Sscrofa11.1) using STAR software (v2.7.6a)14. Kallisto (v0.44.0)15 was used to quantify gene expression in transcripts per kilobase per million mapped reads (TPM). Based on TPM values, t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) analysis was performed using the Rtsne package (v0.17)16,17, and Spearman correlation coefficients between sample pairs were calculated to generate a correlation heatmap.

Gene expression profiling across regions

The tissue specificity of gene abundance reflected by the tau score (τ)18 (ranging from 0 to 1, with 1 for highly tissue-specific genes and 0 for ubiquitously transcribed genes) for each gene with TPM values was calculated. For each tissue, we averaged all replicates and then calculated. We used τ ≥ 0.75 as the cutoff for tissue-specific genes. DEGs were identified using DESeq2 (v.1.45.0)19 based on the reads count data. Significant DEGs were screened with a false discovery rate <0.05 and |log2 fold change| ≥ 1 as cutoffs. Muscle fiber proportions in all samples were estimated based on previous reference profile20 using CIBERSORT platform (https://cibersort.stanford.edu/)21.

Functional enrichment analysis

Functional enrichment analyses were performed using Metascape (http://metascape.org)22 with default parameters. Pig genes were converted to mouse orthologs, and the target gene lists were uploaded as inputs for enrichment. We chose mouse (Mus musculus) as the target species, and enrichment analysis was performed against all genes in the genome as the background set. Only GO and KEGG terms with a P value < 0.01 and annotated to ≥3 genes were considered significant.

Statistical analyses

All results in Fig. 4d were expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE). The significance of the difference was calculated by Wilcoxon rank-sum test in Fig. 4d, and P values < 0.05 was considered significant.

Data Records

The RNA-Seq data of pig skeletal muscles have been deposited into the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (accession number: GSE29789523) with SRA accession number SRP53950713. The processed data files were uploaded together to the GEO repository. The table named “The tissue specific genes for each location of muscle tissue” has been deposited with figshare repository11.

Technical Validation

Sequencing quality control. Total 364.63 Gb clean sequencing reads were generated from 54 libraries with an average of 6.75 Gb for each sample. Mapping the clean data to the pig reference genome (Sscrofa11.1) using STAR alignment, showed that the number of clean reads per sample ranged from 15.57 to 23.98 million, with an average of 22.52 million and an average input read length of 300 bp (2 × 150 bp). Uniquely mapped reads averaged 21.34 million, representing 94.76% of the total average reads (Supplementary Table 1).

Usage Notes

These datasets will provide valuable information for the study of sepsis-induced muscle atrophy and can help researchers to deepen their understanding of the muscle fiber characteristics of the Chinese minipig. In addition, these data can be used to complement studies that analyze muscle tissue heterogeneity among multiple species. We observed the differences between the ZBED6 knockout sepsis group and the control group of minipigs and characterized the mRNA profiles. However, these data can be used to make comparisons with other sepsis models, especially with respect to sepsis-induced muscle atrophy. Beyond that, the data can be used for studies of muscle development in porcine species and for comparisons with females, as well as between multiple species.

Code availability

Code files are available from the GitHub repository https://github.com/YMSen/Paper-Transcriptome-of-sepsis-model-pigs. All the bioinformatics analyses were performed in R 4.4.0 on x86_64-pc-linux-gnu (64-bit) platform, running under CentOS Linux release 7.9.2009 (Core). The following software packages were used in this study: STAR v2.7.6a, kallisto v0.44.0, Rtsne v0.17, ggplot2 v3.5.1, ggforce v0.4.2, DESeq2 v1.45.0, dplyr v1.1.4, UpSetR v1.4.0, pheatmap v1.0.12, gprofiler2 v0.2.3, CIBERSORT v0.1.0.

References

Knox, D. B., Lanspa, M. J., Kuttler, K. G., Brewer, S. C. & Brown, S. M. Phenotypic clusters within sepsis-associated multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med 41, 814–822, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-3764-7 (2015).

Gotts, J. E. & Matthay, M. A. Sepsis: pathophysiology and clinical management. Bmj 353, i1585, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1585 (2016).

Dumitru, A., Radu, B. M., Radu, M. & Cretoiu, S. M. Muscle Changes During Atrophy. Adv Exp Med Biol 1088, 73–92, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1435-3_4 (2018).

Poulsen, J. B. Impaired physical function, loss of muscle mass and assessment of biomechanical properties in critical ill patients. Dan Med J 59, B4544 (2012).

Käser, T. Swine as biomedical animal model for T-cell research-Success and potential for transmittable and non-transmittable human diseases. Mol Immunol 135, 95–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2021.04.004 (2021).

Lunney, J. K. et al. Importance of the pig as a human biomedical model. Sci Transl Med 13, eabd5758, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abd5758 (2021).

Sjöstedt, E. et al. An atlas of the protein-coding genes in the human, pig, and mouse brain. Science 367, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay5947 (2020).

Walters, E. M. & Prather, R. S. Advancing swine models for human health and diseases. Mo Med 110, 212–215 (2013).

Zanders, L. et al. Sepsis induces interleukin 6, gp130/JAK2/STAT3, and muscle wasting. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13, 713–727, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12867 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Porcine ZBED6 regulates growth of skeletal muscle and internal organs via multiple targets. PLoS Genet 17, e1009862, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1009862 (2021).

Maosen, Y. Tissue specific genes for each location of muscle tissue. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29126426.v1 (2025).

Liu, H. et al. Loss of ZBED6 Protects Against Sepsis-Induced Muscle Atrophy by Upregulating DOCK3-Mediated RAC1/PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway in Pigs. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany) 10, e2302298, https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202302298 (2023).

Huan, L. et al. Gene expression characteristics of sepsis induced muscle atrophy in pigs. NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP539507 (2025).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 (2013).

Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P. & Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol 34, 525–527, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3519 (2016).

Maaten, L. V. & Hinton, G. Visualizing High-Dimensional Data Using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research 9, 2579–2605 (2008).

Maaten, L. V. D. Accelerating t-SNE using tree-based algorithms. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 3221–3245 (2014).

Yanai, I. et al. Genome-wide midrange transcription profiles reveal expression level relationships in human tissue specification. Bioinformatics 21, 650–659, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti042 (2005).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Jin, L. et al. A pig BodyMap transcriptome reveals diverse tissue physiologies and evolutionary dynamics of transcription. Nat Commun 12, 3715, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23560-8 (2021).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods 12, 453–457, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3337 (2015).

Zhou, Y. et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun 10, 1523, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6 (2019).

Huan, L. et al. Gene expression characteristics of sepsis induced muscle atrophy in pigs. NCBI GEO https://identifiers.org/geo/GSE297895 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center Clinical Science and Technology Innovation Project (Grant No.SHDC22021316), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82270087 and No. 82300100), Physician-Scientist Project of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Grant No. 20240804), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFC3044600) and Aeromedical Research Funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L., W.S. and Y. Z. conceived and designed the experiments and the analytical strategy. S.Y. and Y.Z. performed animal work and prepared biological samples. H.L. and H.W. constructed the cDNA library and performed sequencing. M.Y., Z.Y. and H.L. designed the bioinformatics analysis process. W.S. and Y.Z. submitted the dataset. H.L., H.S., E.C. and Y.C. wrote the paper. E.M., S.H., E.C. and Y.C. revised the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Shi, W., Zheng, Y. et al. Bulk RNA-seq of skeletal muscle reveals the role of ZBED6 in sepsis-induced muscle atrophy in minipigs. Sci Data 12, 1312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05620-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05620-6