Abstract

We present a publicly available dataset, offering annotated full-body kinematics, gaze tracking, and ground reaction forces and moments from 48 healthy young adults performing a life-size suprapostural task. Using a 12-camera motion capture system, eye tracker, and force plate, we recorded full-body kinematics, eye gaze and pupil diameter, and ground reaction forces and moments as participants completed four tasks: standing upright, performing the Trail Making Test (TMT) Part A projected on a screen using a laser pointer and repeating these conditions on a wobble board inducing instability along the mediolateral axis. Each trial lasted five minutes, and the total number of trail connections was recorded. The dataset comprises raw and processed data on TMT trajectories, individual performance scores, video recordings of the TMT, full-body kinematics, the center of mass (CoM), joint angles, eye gaze and pupil diameter, ground reaction forces and moments, and the center of pressure (CoP). This resource provides an unprecedented opportunity to investigate balance, motor control, and cognitive performance during concurrent suprapostural tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The conventional approach to studying human movement dexterity often fragments the body’s capabilities into isolated components, focusing on motor control, muscle tone, posture, or cognition as independent systems. This reductionist view overlooks the true nature of dexterity, which is inherently a whole-body phenomenon requiring coordinated action across multiple systems1,2,3,4,5,6. Dexterity should not be dissected into parts but understood as a unified, integrated process spanning the entire body7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. For instance, fluctuations in posture create movements that generate visual information, or optic flow, about objects and their spatial relationships. This constant feedback loop allows the postural system to adjust dynamically, maintaining a poised state ready for interaction with the environment17,18,19,20. Thus, the body’s functionality is inseparable from its anatomical components, especially during tasks requiring balance and posture. Studying dexterity as a whole-body coordination process is essential to understanding how humans manage complex tasks while standing upright.

Building on the recognition that dexterity is a whole-body coordination process, recent research has increasingly focused on the intricate interplay between posture control and secondary cognitive tasks—often referred to as “suprapostural” tasks or the phenomenon of “dual-tasking.” This line of work sheds light on simultaneous cognitive demands imposed by maintaining posture while performing other tasks (see reviews21,22,23,24,25). Although patterns of interaction between postural and suprapostural tasks differ across studies, several critical insights have emerged. For example, some studies demonstrate reduced postural sway during cognitive tasks compared to standing still, as the body becomes more focused on the secondary task23,26,27,28,29, but when postural demands increase, cognitive task performance tends to decline26,30,31. Conversely, increasing the attentional load of the cognitive task often results in greater postural sway32,33,34,35,36. The complexity of these interactions is further heightened when precise hand-eye coordination is required alongside challenging postural demands37,38,39. Despite the many task configurations studied, what remains unclear is the full scope of how whole-body coordination underpins and is influenced by these concurrent tasks—especially in scenarios where maintaining stability and engaging with the environment place competing demands on the body’s coordination systems. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for advancing our knowledge of how human movement operates in real-world settings.

Understanding whole-body coordination is crucial, especially for rehabilitating older adults and clinical populations with diminished dual-tasking abilities. Older adults, for instance, are more prone to falls when performing manual tasks while standing or walking40,41,42,43. Age-related declines manifest in impaired limb coordination44,45,46, difficulties in hand-eye coordination47,48,49, reduced attentional capacity50,51, and general cognitive slowing52,53; left unaddressed, these issues can lead to a cascade of falls, posing serious risks to the health and safety of older adults54,55. This vulnerability is even more pronounced in clinical populations with neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinsonism31,56,57,58,59. Traditionally, dual-task performance has been studied piecemeal, focusing on individual components such as motor control, posture, or cognition. This fragmented approach may explain why previous rehabilitative efforts targeting balance or cognitive function in isolation have often produced limited results60,61,62. Adopting a more integrated view that acknowledges the body’s holistic coordination is essential to achieve meaningful improvements, transcending its parts’ separability63,64. As a first step toward understanding the nature of global coordination during dual-task performance, it is critical to establish a baseline using multimodal data from healthy young adults. The present dataset aims to provide this foundation, offering a valuable resource for researchers exploring suprapostural and dual-task performance from a whole-body coordination perspective.

Despite decades of research on postural control—especially during quiet standing—the availability of publicly accessible datasets containing ground reaction forces and moments remains surprisingly limited. This scarcity is puzzling because recording ground reaction forces and moments with force plates is a standard, straightforward procedure in most gait labs. Even rarer, however, are datasets that provide full-body kinematics, essential for calculating collective dynamical variables like the center of mass (CoM) and center of gravity (CoG). Notable exceptions to this include a few valuable datasets that explore postural sway under various conditions, such as those by Priplata et al.65, Santos et al.66, and Dos Santos et al.67, as well as research on specific clinical populations like those by Sbrollini et al.68 and De Oliveira et al.69.

-

Priplata et al.65 describe a dataset of postural sway measurements for 15 healthy young and 12 healthy old participants. Each participant’s postural sway was recorded during a series of 30-second trials. During the trials, participants wore gel-based insoles in each shoe, incorporating vibrating elements positioned beneath the forefoot and heel. Some conditions involved vibrations generated using a digitized uniform white noise signal.

-

Santos et al.66 provide a publicly accessible dataset containing ground reaction forces and moments. The dataset comprises 163 adults of varying ages who underwent 60-second periods of standing still under four conditions: on a rigid or foam surface with eyes open or closed. Several tests were also administered to better characterize each participant, including the Short Falls Efficacy Scale International, International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Version, and Trail Making Test. Participants were also interviewed to gather sociocultural, demographic, and health-related information.

-

Dos Santos et al.67 detail a publicly available dataset encompassing three-dimensional kinematics of the entire human body, ground reaction forces, and moments obtained using a dual force platform setup. The dataset includes information from 27 young and 22 old participants who underwent 60-second periods of standing still under various conditions, with manipulations to participants’ vision and the standing surface.

-

Sbrollini et al.68 present a collection of postural data obtained from 10 patients diagnosed with Stargardt’s syndrome, a rare genetic eye disease characterized by the buildup of fatty material on the macula—the central part of the retina responsible for sharp vision. Data from 10 healthy control participants were also included for comparison. Each participant underwent 60-second periods of standing still under different conditions, including eyes closed, eyes open while fixating on a still target, and eyes open while fixating on a moving target.

-

De Oliveira et al.69 detail a publicly available dataset comprising 32 idiopathic older adults diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. The dataset includes 30-second periods of standing still under various conditions, with manipulations to both participants’ vision and the standing surface. Importantly, the data were collected while these patients were both on and off levodopa medication, providing insights into the effects of medication on postural control in Parkinson’s disease.

However, no publicly available datasets currently focus on suprapostural tasks, particularly those involving complex dual-tasking paradigms like the Trail Making Test (TMT). This lack of comprehensive datasets makes it difficult to pilot-test hypotheses about whole-body coordination during such tasks, where the interplay between posture and secondary task performance is critical. The absence of these resources creates a significant gap in the field, limiting our ability to fully explore and understand mechanisms of human motor control and cognition in real-world dual-tasking scenarios. Filling this gap is essential for advancing both fundamental research and applied interventions, particularly in populations prone to postural instability, such as older adults and those with neurodegenerative conditions.

To address this gap, we present a publicly available annotated dataset collected from 48 healthy young adults performing a life-size suprapostural task inducing instability mainly along the anteroposterior (AP) axis. This dataset encompasses a comprehensive range of variables, including TMT trajectories, individual performance scores, video recordings of the TMT, full-body kinematics, the center of mass (CoM), joint angles, eye gaze and pupil diameter, ground reaction forces and moments, and the center of pressure (CoP). Full-body kinematics were captured using a 12-camera motion capture system, and participants completed two five-minute trials across four experimental conditions: standing upright, performing a life-size TMT while standing, and repeating both tasks while balancing on a wobble board, inducing instability mainly along the mediolateral (ML) axis.

This dataset represents a pioneering resource for exploring whole-body coordination during suprapostural tasks. It is distinguished by meticulous attention to data acquisition and processing methodologies, addressing common discrepancies in kinematic data that have hindered consistent interpretation in previous research70. The dataset provides detailed documentation on coordinate systems, joint angles, Euler angle sequences, gap filling, and force/moment calculations. This rigorous approach ensures a robust and transparent methodological framework designed to minimize misinterpretations and enhance the reliability of future research. By offering this comprehensive and precisely curated data, we aim to advance the understanding of whole-body coordination in complex motor tasks and support more accurate and insightful analyses in the field. This dataset was previously analyzed in two studies that focused specifically on postural control71,72, examining the dynamics of the CoP to uncover insights into balance and stability mechanisms. Those studies derived non-Gaussian and fractal variables from CoP data, representing only a small subset of the present dataset. In contrast, the current dataset provides a much broader scope, incorporating full-body kinematics, gaze tracking, ground reaction forces, and moments, offering a comprehensive, multimodal perspective on human movement. This dataset will help further investigate the interplay between postural control and whole-body coordination, enabling researchers to understand the mechanisms underlying complex suprapostural behaviors.

Previous studies and associated datasets have been constrained either by datasets focusing on isolated movement components or analytical methods failing to capture the dynamic interaction between cognitive demands and whole-body coordination. This dataset bridges that gap by providing the necessary multimodal data and the opportunity to develop new analytical frameworks for understanding the interactions between postural stability, visuomotor control, and cognitive processing, allowing for a more holistic understanding of whole-body coordination. This dataset enables an in-depth investigation of how cognitive demands shape motor adaptation by embedding prospection—the anticipatory process of searching for the next number and planning laser pointer movements—into a complex visuomotor task. The multidimensional approach offers new insights into human performance, aging, and disease-related motor decline, establishing a benchmark for studying suprapostural control across different populations. Given the profound influence of cognitive, neurological, physiological, nutritional, and pathological factors on task adaptation, this dataset is a critical resource for advancing clinical assessments, rehabilitation strategies, and movement science research.

Methods

Participants

Forty-eight healthy young adults aged 19 to 35 years (mean ± s. d. age: 26 ± 4.3 years, free from musculoskeletal or neurological conditions that could affect their suprapostural task performance, participated after providing verbal and written consent approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Nebraska Medical College, Omaha, NE (Study No. 0055-23-EP). The group comprised twenty-four men and twenty-four women, allowing for the exploration of sex as a biological variable in future analyses of this dataset.

Wobble board: Inducing [mechanical] postural instability along the ML axis

To investigate the effects of mechanical postural instability on whole-body coordination, we used a l × w × h = 44.5 × 35.0 × 9.5 cm wobble board inducing instability specifically along the ML axis (Fig. 1). The wobble board used in this study follows a standard unidirectional design, featuring a flat top surface and three cylindrical supports underneath that enable rolling motion along the ML axis. The smooth surface of the force plate minimizes rolling resistance, ensuring consistent movement dynamics. To prevent slipping, friction-enhancing coatings are applied to the board and its support components. This ML axis instability specifically challenges the control systems involved in lateral balance, providing an ideal environment to assess postural responses and adaptive mechanisms.

The experiment used a rectangular wobble board with instability constrained along the ML axis rather than a circular omnidirectional one to provide a controlled yet destabilizing postural challenge that aligns with common real-world balance demands, such as those encountered while standing, walking, or navigating uneven terrain. An omnidirectional wobble board would introduce greater postural instability in multiple directions, potentially leading to excessive variability in movement responses that could obscure meaningful patterns of whole-body coordination. By restricting instability to the ML axis, the study ensures greater consistency across trials, facilitating clearer interpretations of how postural control, cognitive load, and whole-body coordination interact. This design choice also reflects prior research demonstrating that ML balance control is more cognitively demanding than AP control, making it particularly relevant for investigating suprapostural task integration and cognitive-motor interactions.

Trail Making Test (TMT): Inducing [cognitive] postural instability along the AP axis

The TMT is a neuropsychological test providing information about a range of cognitive processes, including attention73, visual search and scanning speed74,75, flexibility76,77, and psychomotor skills59,78. The most commonly used version of the TMT consists of two parts, A and B79. In TMT Part A, the participant uses a pencil to sequentially connect 25 encircled numbers in numerical order. Part B requires connecting 25 encircled numbers and letters in an alternating numerical and alphabetical sequence. For example, the sequence starts with “1,” followed by “A,” then “2,” followed by “B,” and so on. The arrangement of numbers and letters is semi-randomized to prevent overlapping lines. The primary variables of interest are the total completion times for parts A and B. A cutoff time of five minutes is typically applied, representing the maximum achievable score. Specific cutoff thresholds have been proposed based on the total time to complete practice versions of the tests80. TMT Part A is commonly regarded as assessing visual search and motor speed skills, while TMT Part B is viewed as testing higher-level cognitive functions such as mental flexibility75. However, there is ongoing debate regarding the accuracy of these tests in measuring distinct cognitive domains. The total completion times for parts A and B are key variables of interest. Some clinicians and researchers also calculate a B − A difference or a B/A ratio to indicate the degree of interference from the flexibility component of part B. This study used a modified version of TMT Part A with numbers 1–100 randomly situated in a 10 × 10 grid projected on a 1.80 × 1.80 m screen (Fig. 2). Participants had five minutes to complete the TMT during each task, with performance assessed based on the number of connections made within this duration.

Tasks, procedure, and instructions to participants

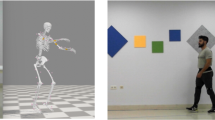

We tested participants in an indoor laboratory in the Biomechanics Research Building at the University of Nebraska at Omaha (Fig. 3). After obtaining informed consent, we fitted participants with retroreflective markers and an eye tracker. The TMT Part A was presented on the projector screen and involved drawing a trail through jumbled numbers. In the “no wobble board, no TMT” condition, participants stood directly on the force plate and maintained an upright stance for five minutes (Fig. 3a). In the “no wobble board, TMT” condition, participants stood on the force plate and performed the TMT using a laser pointer while maintaining an upright stance for five minutes (Fig. 3b). In the “wobble board, no TMT” condition, participants stood on an ML axis-oriented wobble board and maintained an upright stance for five minutes (Fig. 3c). In the “wobble board, TMT” condition, participants stood on the same ML axis-oriented wobble board, performed the TMT using a laser pointer, and maintained an upright stance for five minutes (Fig. 3d). Participants completed two trials of each condition, with the order of the 8 trials (4 conditions × 2 trials) pseudorandomized. We did not provide specific instructions on posture to avoid influencing participant attention and postural control strategies81. Instead, we instructed participants to ensure that the edge of the wobble board did not touch the force plate. Each TMT trial featured a different randomized sequence of numbers to minimize potential learning effects. The TMT was presented during task and no-task conditions to maintain uniformity across all experimental scenarios.

Experimental setup. We employed a support surface and task combination involving a wobble board, introducing mechanical instability along the ML axis, and a body-sized, modified Trail Making Task (TMT) Part A, which mainly imposed visual demands along the AP axis. Participants stood either on a force plate or a wobble board and, in both conditions, either maintained an upright stance or traced a path through randomly projected numbers on a screen. (a) No wobble board, no TMT—standing upright (baseline condition). Participants stood upright on a stable surface, with full-body kinematics, eye gaze and pupil diameter, and ground reaction forces and moments recorded. This condition serves as the baseline for assessing postural adaptation to mechanical and cognitive postural perturbations. (b) No wobble board, TMT—TMT Part A while standing upright. Participants performed the TMT Part A using a laser pointer while standing upright on a stable surface. This condition tests cognitive-motor coordination under stable postural conditions. (c) Wobble board, no TMT—standing on a mediolaterally oriented wobble board. Participants stood on a mediolaterally oriented wobble board, inducing instability primarily along the mediolateral axis. Full-body kinematics, eye gaze and pupil diameter, and ground reaction forces and moments were recorded to assess postural control under unstable conditions. (d) Wobble board, TMT—TMT Part A while standing on a mediolaterally oriented wobble board. Participants performed the TMT Part A using a laser pointer while standing on a mediolaterally oriented wobble board. This condition tests cognitive-motor coordination under unstable postural conditions.

Stabilography

Participants stood either directly on a 40 × 60 cm floor-embedded force plate (400600HPSTM, AMTI Inc., Watertown, MA) or on a wobble board placed over the force plate. Strain gauge transducers within the plate measured the ground reaction forces and moments under the participants’ feet, converting mechanical strain into electrical signals. The sampling rate was 1, 000 Hz, consistent with the protocol of the larger study. These ground reaction forces and moments were used to calculate postural CoP along the ML and AP axes.

Motion tracking

Participants wore form-fitting exercise clothing and were barefoot for data collection. Twenty-nine retroreflective markers were placed on each participant’s body using a modified Helen Hayes marker set (Fig. 4; Table 1), widely used in biomechanics research due to its standardized placement, validated in clinical and research environments. Standardization ensures reliable and reproducible data collection, consistent body segments, and joint movement tracking, and minimizes participant discomfort. To minimize movement artifacts during motion capture, a tight rubber cap was placed on the participant’s head to attach retroreflective markers securely. Additionally, three retroreflective markers were placed on the laser pointer used during the TMT, and four markers were positioned at the corners of the wobble board. Four additional markers were placed on the projector screen.

Modified Helen Hayes marker arrangement used for 3D motion capture. See Table 1 for detailed marker descriptions and placement information.

To calibrate the whole-body biomechanical model for accurate tracking, model fitting, and data analysis, participants stood on a force plate with their feet apart and assumed a “T” pose, raising their arms to approximately 90 degrees and holding the position for five to seven seconds. During calibration, the laser pointer rested on the equipment table, while the wobble board was placed on the floor near the force plate, within the visual field of the cameras. Retroreflective markers on the laser pointer and projector screen allowed precise tracking of the laser pointer’s movements, with its position extrapolated from a straight-line vector based on the markers attached to the pointer. Marker trajectories were recorded in 3D at 100 Hz using a 12-camera motion capture system (Kestral 4200TM, Motion Analysis Corp., Rohnert Park, CA). Marker trajectories and force plate data were hardware-synchronized through the Motion Analysis Corporation’s data acquisition interface, ensuring precise frame-by-frame temporal alignment across both systems.

Eye tracking

Participants wore eye-tracking glasses (Glasses 2TM, Tobii Technology Inc., Stockholm, Sweden), recording 2D eye gaze coordinates at 1, 000 Hz. For participants with prescription glasses for visual correction, efforts were made to match the lenses in eye-tracking glasses to their prescription, ensuring optimal visual clarity. No adjustments were necessary for participants wearing contact lenses or without visual correction. Calibration of the eye-tracking system involved participants looking at a calibration card provided by Tobii, allowing precise alignment of internal sensors and glasses to each individual. Additionally, participants held a single retroreflective marker at arm’s length while maintaining visual focus on it, facilitating calibration of Tobii to their gaze. The eye tracker was also equipped with four retroreflective markers for motion tracking. It was connected to a transmitter via HDMI, and the transmitter was synchronized with the motion capture system running on CortexTM software (Motion Analysis Corp., Rohnert Park, CA) using WiFi.

Coordinate systems

The center of the force plate was located at coordinates (0.2 m, 1.5 m, 0 m) relative to the origin of the global coordinate system. In this coordinate system, for all kinematic measurements—marker positions and ground reaction forces, the x-axis increases toward the participant’s right, the y-axis increases forward from the participant, and the z-axis increases vertically, aligned with the participant’s height (Fig. 5). This setup allowed for precisely tracking markers and ground reaction forces within a stable and defined global space.

Experimental setup illustrating coordinate systems for biomechanical and eye-tracker data collection. The global coordinate system (x, y, x) is used for motion tracking, while the eye tracker measures eye gaze vector and eye gaze position (x, y). Force plate data is integrated within the biomechanical coordinate system to analyze suprapostural coordination during task performance.

Different coordinate origins and orientations are used for various data types in the Tobii eye tracker output. For 3D eye gaze position coordinates, the origin is typically located at the center of the Tobii eye tracker or a calibrated reference point around the participant. This origin serves as a fixed point in 3D space, with measurements in millimeters indicating the gaze point location relative to this reference. For 2D screen coordinates, the origin is defined as the top-left corner of the screen at (0, 0) pixels, with the x-axis increasing toward the right and the y-axis increasing downward (Fig. 5). The gaze directional vectors are unitless and normalized to represent the direction of each eye relative to the participant’s head, originating from the respective eye’s position as tracked by the Tobii system. A head-centered coordinate system is used for the accelerometer and gyroscope data, originating at the participant’s head position. In this system, the x-axis is aligned horizontally toward the participant’s left side, the y-axis is aligned vertically, pointing upward, and the y-axis is oriented forward from the face (Fig. 5).

Data synchronization

All multimodal data were recorded synchronously during the experiment using CortexTM software. Synchronization was facilitated by CortexTM Sync Box, which integrates with the data acquisition system to ensure precise alignment across modalities. Sync Box generates a synchronization trigger that sends time markers to the motion capture system and physiological data collection equipment. Each time stamp is logged in CortexTM software, ensuring that the timing of each data stream is accurately recorded in a unified format. This process aligns incoming streams from the motion capture system, eye tracker, and force plates. All peripheral equipment used in the experiment was fully compatible with CortexTM, eliminating the need for additional or third-party hardware. CortexTM enables seamless digital integration of AMTI force plates and supports direct and wireless data streaming from the Tobii eye tracker. Data recording triggers and motion capture system zeroing are managed directly through CortexTM, consolidating live-streaming data from peripheral devices, including eye-tracking glasses and force plates. This integration allowed real-time monitoring of force plate outputs and eye gaze vectors, ensuring continuous, unobstructed, and precise data collection throughout each recording session.

Data processing

Addressing data gaps in motion capture

Biomechanical research using motion capture requires addressing gaps in data caused by occlusions or marker loss. Researchers commonly use virtual markers when they have enough physical markers on relevant body segments. During static calibration trials, participants hold a predefined posture, allowing researchers to place reference points on rigid body segments. These reference points help reconstruct trajectories of missing markers during dynamic trials. However, this study could not use virtual markers due to an insufficient marker setup. Instead, we estimated missing data using cubic spline interpolation, a standard technique in such situations. This method ensured smooth, continuous reconstruction of missing kinematic data, adhering to physiological expectations82,83, and contributed to the consistency of kinematic analysis.

Determining the postural center of mass (CoM)

We applied the Dempster model84 to assess body segment mass distribution and spatial orientation, while the Hanavan model85 calculated segment inertia. We estimated hip joint centers using a geometric approach by Bell et al.86, which relies on relative positions of the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) markers to define hip joint orientation. We used positions of ASIS and sacral markers to model pelvic motion dynamics. Similarly, we determined shoulder joints based on the positions of both shoulder markers to ensure accurate upper limb modeling. We estimated the knee and ankle joint centers using medial and lateral marker placements at each respective joint. To further refine the thorax model, we used iliac landmarks from the Terry database87. We used Visual3D® (C-Motion Inc., Germantown, MD) to perform all calculations and biomechanical definitions, seamlessly integrating methods into a unified analysis pipeline to determine postural CoM trajectory for each standing trial.

Determining segments and joints

The definition of body segments followed the standard procedures of the conventional gait model implemented in Visual3D®. For the lower body, the pelvis segment was defined using bilateral anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) markers along with a sacral marker to establish its coordinate system, with the midpoint between the ASIS markers serving as the mediolateral reference. The thigh segments were constructed by defining a proximal hip joint center—estimated using a fixed percentage offset from the ASIS midpoint88—and a distal knee joint center, determined using a percentage-based axial offset from the distal thigh. This approach ensured consistent alignment between the thigh and shank segments. The shank segments extended from the knee joint center to the ankle joint center, which was also defined using an offset-based method. For the upper body, the thorax segment was defined proximally by the right and left iliac landmarks and distally by the right and left shoulder landmarks, with an additional marker used to refine segment orientation. Each upper arm (right and left) was defined as spanning from its respective shoulder joint center to the elbow joint center, with segment alignment refined using an elbow marker. The forearm segments extended from the elbow joint centers to the wrist joint centers, again incorporating additional markers to improve orientation. The centers of both the elbow and wrist joints were calculated using percentage-based axial offset methods, ensuring consistency across participants and trials.

Determining joint angles

We computed joint angles by combining marker trajectories obtained from the motion capture system with ground reaction forces and moments recorded by the force plates, using Visual3D® software. Joint angle calculations were based on the anatomical coordinate system of the proximal segment, following the recommendations of the International Society of Biomechanics (ISB)89,90. Marker trajectories were first processed and mapped onto a predefined skeletal model to identify joint centers and establish segment orientations. Joint angles were then calculated through coordinate transformations that aligned the local coordinate systems of adjacent segments, following the biomechanical model developed by Grood and Suntay91. This approach ensured consistent, anatomically meaningful joint angle estimation across participants and trials.

Determining the postural center of pressure (CoP)

We used the ground reaction forces and moments recorded by the force plate to compute postural CoP along the AP and ML axes using the formula:

where CoPML(t) and CoPAP(t) are the coordinates of the CoP along the ML and AP axes at timepoint t and Mx(t), and My(t), Fz(t) are directional components of the moments and forces acting on the body from the force plate.

Signal processing

We chose to publish raw, rather than filtered, kinematic marker trajectories to maximize the utility of our dataset, ensuring that our findings can be fully reproduced and that subsequent analyses remain unbiased by any initial processing choices. Providing raw data allows other researchers the flexibility to apply their filtering and preprocessing methods, enabling them to tailor analyses to a broad range of research questions and methodological needs. While we recognize the value of filtering in specific applications, offering raw data best preserves the dataset’s integrity and enhances its reusability for diverse scientific inquiries.

In contrast, we have provided filtered CoP and CoM trajectories alongside the raw marker data. These specific trajectories are often derived from complex calculations involving the integration of multiple markers and force plate data and, thus, are particularly sensitive to high-frequency noise. Providing filtered CoP and CoM data ensures that these critical components are immediately usable for analysis, minimizing the need for extensive preprocessing. However, we recognize the importance of flexibility and transparency, so we have included detailed information on the filtering parameters, allowing researchers to replicate or adjust the filtering process. To calculate CoP and CoM trajectories directly from raw marker and force plate data, we provide comprehensive details to support accurate processing and analysis tailored to specific research needs.

Our filtering choices were guided by an in-depth understanding of postural control mechanisms, which function hierarchically across multiple temporal and neural scales to maintain stability. This system comprises short-latency reflexes (SLRs), long-latency reflexes (LLRs), and compensatory postural adjustments (CPAs), each contributing uniquely to balance. As the stretch reflex exemplifies, SLRs provide the quickest response (20–50 ms) to perturbations, initiating rapid stabilization92,93. LLRs, occurring within 50–100 ms, bridge the gap between SLRs and CPAs by engaging higher-level neural processing to refine muscle activity for sustained balance, with response magnitudes modulated by individual and protocol-specific factors94,95,96,97. CPAs, which appear after 100 ms, involve coordinated muscle and joint movements to adapt posture98,99,100.

Though these mechanisms overlap temporally, each has distinct neural pathways and functions. SLRs and LLRs rely heavily on muscle afferents, with SLRs specifically mediated by the group I afferents101. LLRs utilize group I afferents but engage both spinal and supraspinal pathways102,103,104,105,106. Conversely, CPAs integrate broader somatosensory inputs107,108 and recruit higher neural centers, including the premotor cortex and basal ganglia109,110,111,112,113,114. Together, these mechanisms operate in a cascading manner115: initial perturbations prompt responses via SLRs and LLRs, while CPAs provide longer-term adjustments that reshape and stabilize postural responses17,18,116,117. The integrated nature of these mechanisms necessitates preserving all components through careful filtering, particularly for those aiming to analyze cross-scale interactions in postural control13.

We applied a Butterworth filter with a 60 Hz cutoff frequency to the CoP trajectories along the AP and ML axes, ensuring that key SLR, LLR, and CPA components were retained. The Butterworth filter, known for its maximally flat frequency response in the passband, minimizes signal distortion by avoiding ripples that could compromise signal integrity118. For CoM trajectories (obtained using unfiltered marker positions), we used a Butterworth filter with a lower cutoff frequency of 6 Hz. This choice reflects the slower, larger-scale body movements that characterize CoM data compared to the finer, quicker adjustments in CoP data—the 6 Hz cutoff effectively retains these critical low-frequency components of body movement, eliminating high-frequency noise while preserving signal fidelity. Filter design utilized the butter() function to create the filter and the buttord() function to determine the minimum filter order, using the following specifications: a passband edge frequency Wn, a stopband edge frequency Wn + 0.1, a passband ripple of 3 dB, and a stopband attenuation of 40 dB.

Data Records

The data presented in the current paper is available for download from figshare119 and can be used freely for any purpose. The file participantCharacteristics.csv provides detailed demographic and physical characteristics of the participants, including their participant ID, sex, age [years], height [cm], body mass [kg], and self-reported handedness, along with the order of trials. The file TMTscores.csv contains the TMT performance scores for all four TMT trials, recorded for each participant.

All raw data from each participant, condition, and trial is provided as .txt files organized into separate folders within a standard datatype.zip file, making it easy to access and process the data without requiring proprietary software. The dataset includes TMT, full-body kinematic data, gaze data, and ground reaction forces and moments. This organization simplifies downloading and managing the dataset, particularly for researchers focusing on specific data types. We have included a Matlab script, processBiomechanicsData.m, which curates and preprocesses the raw data to support data analysis. This script consolidates data across participants, conditions, and trials into a single .mat file, allowing users to apply filters and processing steps efficiently. While the Matlab script streamlines data preparation for Matlab users, the raw .txt files ensure compatibility with alternative platforms like Python or R, enabling flexible analysis workflows. For additional support or guidance in data processing, researchers are encouraged to contact Madhur Mangalam (mmangalam@unomaha.edu).

Each .zip file is organized by individual participants, with all files for a specific participant contained in a dedicated folder. Within the TMT folder, two subfolders provide additional details: the layout folder contains the layout of the TMT projected on the screen in each trial in .jpg format, while the videos folder includes video recordings of the TMT trials in .mkv format. These multiple file within individual participant folders p01 through p48 follow the naming convention p#_condition_trial.txt, where # represents the participant index, condition represents the condition, which is Static: ”static calibration trial,” NBNT: “no wobble board, no TMT,” NBWT: “no wobble board, TMT,” WBNT: “wobble board, no TMT,” and WBWT: “wobble board, TMT,” trial represents the trial number. The subsequent folders contain multiple .txt files within individual participant folders p01 through p48, corresponding to data recorded from a single participant for a single condition and follow the naming convention p#_condition_trial_datatype.txt, where # represents the participant index, an integer ranging from 01 to 48, condition represents the condition, which is Static: ”static calibration trial,” NBNT: “no wobble board, no TMT,” NBWT: “no wobble board, TMT,” WBNT: “wobble board, no TMT,” and WBWT: “wobble board, TMT,” trial represents the trial number, which is either 01 or 02, and datatype is one of the following datatypes: pointerProjection, pointerPath, markerPosition, CoM, jointAngle, eyeGaze, pupil, groundReactionForce, and CoP. The Static file exists only for markerPosition, groundReactionForces, and CoP. Each file comprises a collection of variables, outlined in Table 2, collectively representing the data and associated with the corresponding participant, condition, and trial. The variable T indicates the total number of sampled time points throughout the five-minute recording session.

The dataset is organized into data-type-specific folders, housing raw and processed data on TMT trajectories, individual performance scores, video recordings of the TMT, full-body kinematics, CoM, joint angles, eye gaze and pupil diameter, ground reaction forces and moments, and CoP in individual participant-specific folders.

-

The layout files p#_condition_trial.jpg serve as a reference for interpreting the laser pointer trajectories captured during the TMT. These trajectories can be analyzed using the file p#_condition_trial_pointerProjection, which provides the trajectories based on the projection of markers attached to the laser pointer on the screen, and the file p#_condition_trial_pointerPath.txt, which contains the pixel coordinates extracted from videos of TMT performance. Although we have already furnished the coordinates of the laser pointer on the projector screen within the variable pointerProjection, the videos p#_condition_trial.mkv hold potential for further secondary analysis or for gaining insight into participants’ performance in the TMT. Together, these resources allow for a comprehensive analysis of the laser pointer’s movement during the test.

-

The files p#_condition_trial_markerPosition.txt contain the positions of markers used in the study. Note that markers were placed directly on the wobble board for participants 20 and onward. Consequently, any analysis requiring wobble board dynamics should either focus exclusively on these participants or infer wobble board dynamics using the markers attached to the participants’ feet. Additionally, the medial ankle and knee angles were utilized solely during the static trials to calibrate the biomechanical model. These markers were excluded during the dynamic trials to prevent interference or redundancy in the analysis, as their role was limited to establishing accurate joint alignment and segment orientation during the initial calibration phase.

-

The files p#_condition_trial_CoM.txt contain time series data for CoM, computed from marker trajectories and a biomechanical gait model using Visual3D®, with a low-pass filter applied at a 6 Hz cutoff. CoM was derived from marker positions before filtering, preserving the original signal’s integrity. This method minimizes distortion, which is crucial for accurately capturing subtle CoM dynamics during tasks like wobble board movements120.

-

The file p#_condition_trial_jointAngle.txt provides data on joint angles for five joints on the left side of the body and five joints on the right side—specifically the ankle, knee, hip, shoulder, and elbow.

-

The file p#_condition_trial_eyeGaze.txt contains time series data for eye gaze position, eye gaze direction, head acceleration, and head rotation. Instances where the eyes blinked, or the pupil was not visible, are indicated by NaN values in the eye gaze position and eye gaze direction data.

-

The files p#_condition_trial_pupil.txt contain time series data for pupil center position and diameter, with NaN values indicating instances where the eyes blinked and the pupil was not visible. NaN values must be carefully handled during analysis, as they represent missing points due to blinks. These NaN values should either be excluded from calculations or interpolated, depending on the study’s goals. Various methods for interpolating missing pupil-size data exist121,122,123,124,– 125; these procedures are sometimes called “blink reconstruction” since blinks are the primary cause of missing data. Additionally, the frequency and duration of NaN values (blinks) may provide insights into blink behavior and might also be considered in the analysis.

-

The files p#_condition_trial_groundReactionForce.txt contain data that can be easily utilized and, when combined with details about the origin of the kinematic space and the center of the force plate, allow for the computation of a wide range of variables as needed.

-

The files p#_condition_trial_CoP.txt contain time series data for CoP, computed from ground reaction forces and moments using Visual3D® after applying a low-pass filter with a 60 Hz cutoff. CoP was calculated from raw ground reaction forces and moments before filtering, preserving the original signal’s integrity. This method minimizes signal distortion, which is critical for accurately capturing subtle CoP shifts during dynamic tasks like wobble board movements, where precise CoP analysis is essential for understanding balance and control120.

Technical Validation

In this section, we validate the reliability of TMT scores as an indicator of cognitive performance under different postural challenges introduced using a wobble board. By comparing TMT performance across various support conditions, we confirm our protocol’s ability to create controlled postural instability, significantly affecting cognitive task execution. This analysis demonstrates the wobble board’s effectiveness in challenging postural control and establishes our dataset’s robustness for secondary analyses. These comparisons ensure that our experimental manipulations produce consistent and measurable effects. Overall, this validation reinforces the validity of our approach in studying the interplay between postural stability and cognitive function.

We examined the effects of postural instability caused by the wobble board and TMT engagement on key variables, including TMT performance and those derived from the collected kinematic data, eye gaze and pupil diameter, and ground reaction forces and moments. The model included the fixed effects of support condition (“WB” for wobble board as opposed to no wobble board), task condition (“TMT” as opposed to no TMT), and trial (“T2” for trial 2 as opposed to trial 1). We included the random factor of participant identity by allowing the intercept to vary across participants. Statistical analyses were performed in R126 using the package lme4127. We set the threshold for statistical significance at the alpha level of 0.05 using the package “lmerTest”128. Corresponding to each coefficient was a standard error (s. e. ), denoting the variability around the mean change in the dependent variable. We present the estimated coefficients from the linear mixed-effect model in the format b ± s. e. , alongside the associated t-statistic, calculated as b/s. e. , and the corresponding p-value.

TMT scores

We compared TMT scores between the two support conditions to validate the protocol’s design and confirm the dataset’s reliability in assessing controlled postural challenges. The wobble board significantly reduced TMT scores from mean ± s. e. = 43.51 ± 1.49 by 2.34 ± 1.00 compared to standing directly on the force plate (t = −2.337, p = 0.021; Fig. 6), highlighting its ability to introduce instability and demand greater postural control. These results validate the experimental setup and support the dataset’s utility in examining the interplay between postural control and cognition.

Performing TMT while standing on the wobble board significantly reduced performance. Violin plots illustrate the distribution of TMT scores in the two support conditions. The gray, thick and thin vertical lines span the 25th and 75 th quartiles, respectively. Horizontal bars indicate group mean, and white circles indicate group median (N = 96; 48 participants × 2 trials/participant). ***p < 0.05.

Kinematics, postural CoP and CoM

To establish the validity of kinematic data, ground reaction forces, and moments collected during the experiment, we critically examined the effects of experimental manipulations on the dispersion of CoP and CoM trajectories. Without a wobble board, CoP and CoM planar trajectories displayed an elongated path primarily along the AP axis (top panels in Fig. 7a,b), consistent with the conventional understanding that postural stability is generally more vulnerable along the AP axis. This observation aligns with the biomechanical principle that human posture is inherently less stable in the AP direction due to a narrower base of support and forward placement of the body’s CoP and CoM relative to the feet. However, the introduction of the wobble board fundamentally altered CoP and CoM trajectories, causing significant expansion of sway along the ML axis (bottom panels in Fig. 7a,b). This expanded ML dispersion indicates an increased challenge to balance imposed by the wobble board. It destabilizes the ML axis’s posture due to its design, requiring greater neuromuscular coordination to maintain equilibrium. Pronounced ML sway observed with wobble board underscores the effectiveness of this experimental manipulation in amplifying demands on postural control, particularly in the ML plane—results, as presented in Fig. 7a,b, provide compelling evidence of the differential impact of experimental conditions on CoP and CoM dynamics. CoP and CoM trajectories for a representative participant demonstrate expected postural adjustments, with an observable shift from AP—dominant to ML—dominant sway due to wobble board intervention. Violin plots in Fig. 7c,d, further corroborate these findings, depicting the distribution of CoP and CoM range across all participants.

The postural analysis revealed a pronounced dispersion of sway along the ML axis, resulting in a more substantial expansion of both CoP and CoM in the ML direction compared to the AP axis. (a) CoP planar trajectories for a representative participant across the four experimental conditions: no wobble board, no TMT; no wobble board, TMT; wobble board, no TMT; and wobble board, TMT. (b) CoM planar trajectories for a representative participant across the four experimental conditions. (c) Violin plots showing the distribution of CoP range along the AP and ML axes across the four experimental conditions for all participants. (d) Violin plots illustrating the distribution of CoM range along the AP and ML axes under the four experimental conditions for all participants. Each violin plot’s right and left halves depict the range of CoP and CoM along the ML and AP axes, respectively. Horizontal bars indicate group mean, and white circles indicate group median (N = 96; 48 participants × 2 trials/participant). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005; ***p < 0.001.

The various linear metrics of CoP provided critical insights into postural stability and control across different conditions. As summarized in Table 3, the path length, sway area, mean velocity, standard deviation of displacement, root mean square displacement, and maximum sway ranges along both the ML and AP axes exhibited clear differences between the wobble board (WB) and no wobble board (NB) conditions, but neither varied with TMT engagement nor across the two trials within any support and task combination. For instance, the significantly greater path length and mean velocity observed during the WBNT and WBWT conditions suggest increased postural sway when participants were tasked with balancing on a wobble board. In contrast, the consistent results across trials indicate reliability in CoP measurements despite variations in the wobble board task. Furthermore, the sway area and displacement metrics reinforce that the wobble board introduces more dynamic challenges to postural control, as evidenced by the increased values compared to the no-task conditions. These findings underscore the significant impact of the wobble board on postural control and demonstrate the consistency of results across trials within each condition. Additionally, they validate the effectiveness of the experimental manipulations, revealing that postural control is primarily influenced by the continuous mechanical instability introduced by the wobble board, while the cognitive instability imposed by the TMT appears to have a lesser effect.

Linear mixed-effects modeling revealed no significant differences in the range of CoP or CoM along AP and ML axes while standing directly on the wobble board (all p > 0.05, except for CoM for “no wobble board, TMT” condition: t = −2.533, p = 0.012). However, when standing on the wobble board, whether performing TMT or not, the range of both CoP and CoM was significantly greater along the ML axis compared to the AP axis (CoP: “wobble board, no TMT:” t = 34.265, p = 1.380 × 10−3; “wobble board, TMT:” t = 29.406, p = 1.080 × 10−5; CoM: “wobble board, no TMT:” t = 21.80, p < 2.000 × 10−16; “wobble board, TMT:” p < 2.000 × 10−16, p = 0.012). Further analysis revealed that standing on a wobble board significantly increased the range of both CoP by 3.699 ± 0.362 cm (t = 10.216, p < 2.000 × 10−16) and CoM by 1.610 ± 0.304 cm(t = 5.301, p = 1.530 × 10−5). This increase was more pronounced along the ML axis compared to the AP axis for CoP by 1.411 ± 0.512 cm (t = 2.755, p = 6.020 × 10−3) and CoM by 6.889 ± 0.430 cm (t = 16.029, p < 2.000 × 10−16), reinforcing notion that wobble board effectively altered postural control in study participants. Engagement with TMT led to a marginal reduction in the range of CoP by 0.728 ± 0.362 cm (−2.010, 0.045) but showed no effect on a range of CoM (p > 0.05).

Distinct sway patterns observed across four experimental conditions, particularly increased dispersion with the wobble board, confirm the setup’s effectiveness in altering postural demands as designed. Consistency of these patterns across all participants, supported by group mean and median, underscores the reliability and validity of experimental conditions. Results validate that manipulations successfully elicited expected postural responses, highlighting the setup’s ability to detect subtle changes in postural stability. Findings support the use of this experimental paradigm in exploring mechanisms of postural control. Additionally, the dataset proves valuable for examining how external perturbations and cognitive tasks influence postural stability.

Eye gaze

To establish the technical validity of eye gaze for subsequent analyses, such as examining selective attention to a specific number on screen129,130,131, it is essential to rigorously examine the accuracy and consistency of gaze data across varying experimental conditions. Data presented in Fig. 8 provide robust validation of our dataset for secondary analysis. By comparing eye gaze patterns under four experimental conditions—no wobble board with and without TMT and wobble board with and without TMT—we assessed the influence of both postural instability and cognitive load on visual attention. Consistent calibration across conditions, ensured by the Active Display Coordinate System, allows precise comparisons of gaze behavior. A standardized calibration method, where the Active Display Area ensures the alignment of the eye tracker with the user’s eyes, further solidifies the technical validity of data. The origin of the coordinate system fixed at the upper left corner, with well-defined boundaries at (0, 0) and (1, 1), guarantees that any observed changes in gaze patterns are attributable to experimental manipulations rather than technical inconsistencies. This methodological rigor provides confidence that data on eye gaze is reliable and suitable for secondary analyses exploring the interplay between gaze behavior, postural control, and cognitive tasks.

Eye gaze density across the five-minute trial duration under the four experimental conditions for a representative participant. (a) No wobble board, no TMT. (b) No wobble board, TMT. (c) Wobble board, no TMT. (d) Wobble board, TMT. For eye trackers used without a monitor, as in this study, the “Active Display Area” shows the calibration points when aligning the eye tracker with the user’s eyes. The origin of the Active Display Coordinate System is at the upper left corner of this area, with the point (0, 0) representing the upper left corner and (1, 1) representing the lower right corner.

Pupil diameter

Pupillometry, a method for measuring pupil diameter132, is a well-established proxy for cognitive load, providing an objective and sensitive indicator of mental effort133,134,135,136 and several cognitive faculties137. In this study, an increase in pupil diameter was assessed under four experimental conditions, which combined TMT cognitive demands with mechanical instability introduced by the wobble board. Results, visualized in violin plots in Fig. 9, revealed that both cognitive engagement required for TMT and physical instability caused by the wobble board significantly increased cognitive effort, as reflected in larger mean pupil diameters. Specifically, linear mixed-effects modeling indicated that wobble board increased the mean pupil diameter across the five-minute standing duration from 4.127 ± 0.069 mm by 0.078 ± 0.016 mm(t = 6.633, p = 6.470 × 10−11), while TMT increased it by 0.053 ± 0.016 mm (t = 4.553, p = 6.210 × 10−6; Fig. 9). These findings validate the underlying hypothesis that cognitive and postural demands are interlinked and that the added mechanical challenge of maintaining balance on a wobble board exacerbates cognitive load. Critically, an increase in pupil size due to a wobble board cannot be attributed to physical fatigue, associated with a reduction in pupil diameter138,139,140. This suggests that observed pupil dilation is driven by the cognitive demands of maintaining balance on a wobble board rather than physical exertion. Hence, results reinforce the notion that the body’s response to instability is not just a physical challenge but also a cognitive one, further supporting the use of pupillometry to measure cognitive load in such integrated tasks. Consistency of results across participants and strong statistical significance lend credence to the reliability and robustness of data. This dataset, linking cognitive load with physical instability, provides a strong empirical foundation for future research exploring synergistic effects of cognitive and motor challenges on overall human performance. Additionally, this data can be examined in greater detail, particularly concerning kinematic and ground reaction forces and moments, to test more extensive hypotheses regarding the role of specific gaze behavior in whole-body coordination during challenging suprapostural task performance.

Pupillometry revealed a significant increase in cognitive effort, driven not only by the cognitive engagement required for the TMT but also by the mechanical instability introduced by the wobble board. Violin plots illustrate the distribution of mean pupil diameter across the five-minute trial duration under the four experimental conditions for all participants. Each violin plot’s right and left halves depict the pupil diameter for the right and left eye, respectively. Horizontal bars indicate group mean, and white circles indicate group median (N = 96; 48 participants × 2 trials/participant). ***p < 0.001.

Limitations

During data collection, we encountered a technical limitation due to discrepancies between the frames of reference for gaze data and video recordings of the TMT. Eye-tracking devices typically record gaze coordinates in 2D visual space and overlay these onto an egocentric video of the environment from the viewer’s perspective141,142. Synchronization issues between the eye tracker and CortexTM software presented a challenge: we had to choose between synchronizing one of these with kinematic and ground reaction force data. We chose to prioritize eye gaze coordinates directly from the eye tracker. Additionally, we used an external video camera to capture synchronized footage of the task space from its perspective. While this limitation might affect analyses requiring simultaneous consideration of gaze and laser pointer trajectories within the same visual space, it does not significantly impact analyses focusing on statistical patterns in these trajectories. When considered separately, gaze and laser pointer data remain reliable for such analyses.

The modified Helen Hayes marker set, while appealing for its minimal setup time and established clinical utility, assigns only one or two markers to most distal segments. With fewer than three non-collinear points, a segment’s local reference frame cannot be uniquely resolved in three dimensions, as 3 × 3 rotation matrices become unobtainable. Full 3D joint angles require two fully defined segment-fixed coordinate systems91. As a result, the present model supports complete tri-planar kinematics only at joints where both adjoining segments are sufficiently instrumented—primarily the knee (thigh–shank) and hip (pelvis–thigh), where the shank, thigh, and pelvis each bear at least three well-spaced markers. In contrast, at the ankle, elbow, and wrist, the marker configuration supports accurate flexion-extension estimates but does not allow for reliable computation of abduction/adduction or axial rotation. These constraints informed both the Visual3D® data processing pipeline and the selection of kinematic variables included in the dataset. Accordingly, users will find complete X–Y–Z (Cardan) angles for the hip and knee, whereas other joints are limited to those rotational degrees of freedom that the Helen Hayes geometry can reliably resolve.

Recent studies have identified functional musculoskeletal networks from electromyography (EMG) crucial for maintaining stable gait and posture7,8,11,12. Researchers have also explored neuromuscular interactions by integrating electroencephalography (EEG) and EMG signals in the context of gait and posture143,144,145,146. Incorporating these signals into our current paradigm could offer further insights into suprapostural task performance, especially given previous findings on age- and disease-related changes in neuromuscular contributions147,148,149. However, this study did not include EEG and EMG signals, limiting our analysis to kinematics, gaze, and ground reaction forces and moments. We plan to integrate neuromuscular data in future studies conducted in our lab.

Finally, the study’s exclusive focus on healthy young adults limits its applicability to older adults and individuals with disorders affecting one or more measured variables. Future experiments would benefit from including these additional demographic groups, broadening the scope to cover developmental stages from early childhood through aging and conditions impacting gait and posture. This inclusivity would deepen our understanding of human suprapostural task performance across various life stages and health conditions.

Codes availability

All code for processing and analyzing the present dataset is available as part of the Figshare dataset119.

References

Bernstein, N. The Co-ordination and Regulation of Movements (Pergamon Press, Oxford, UK, 1996).

Chiel, H. J. & Beer, R. D. The brain has a body: Adaptive behavior emerges from interactions of nervous system, body and environment. Trends in Neurosciences 20, 553–557, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01149-1 (1997).

Profeta, V. L. & Turvey, M. T. Bernstein’s levels of movement construction: A contemporary perspective. Human Movement Science 57, 111–133, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2017.11.013 (2018).

Turvey, M. T. Coordination. American Psychologist 45, 938–953, https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.8.938 (1990).

Turvey, M. T. Action and perception at the level of synergies. Human Movement Science 26, 657–697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2007.04.002 (2007).

Turvey, M. T. & Fonseca, S. T. The medium of haptic perception: A tensegrity hypothesis. Journal of Motor Behavior 46, 143–187, https://doi.org/10.1080/00222895.2013.798252 (2014).

Boonstra, T. W. et al. Muscle networks: Connectivity analysis of EMG activity during postural control. Scientific Reports 5, 17830, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17830 (2015).

Boonstra, T. W., Faes, L., Kerkman, J. N. & Marinazzo, D. Information decomposition of multichannel EMG to map functional interactions in the distributed motor system. NeuroImage 202, 116093, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116093 (2019).

Garcia-Retortillo, S. & Ivanov, P. C. Inter-muscular networks of synchronous muscle fiber activation. Frontiers in Network Physiology 2, 1059793, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnetp.2022.1059793 (2022).

Garcia-Retortillo, S., Romero-Gómez, C. & Ivanov, P. C. Network of muscle fibers activation facilitates inter-muscular coordination, adapts to fatigue and reflects muscle function. Communications Biology 6, 891, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-023-05204-3 (2023).

Kerkman, J. N., Daffertshofer, A., Gollo, L. L., Breakspear, M. & Boonstra, T. W. Network structure of the human musculoskeletal system shapes neural interactions on multiple time scales. Science Advances 4, eaat0497, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat0497 (2018).

Kerkman, J. N., Bekius, A., Boonstra, T. W., Daffertshofer, A. & Dominici, N. Muscle synergies and coherence networks reflect different modes of coordination during walking. Frontiers in Physiology 11, 535096, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.00751 (2020).

Kelty-Stephen, D. G. & Mangalam, M. Turing’s cascade instability supports the coordination of the mind, brain, and behavior. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 141, 104810, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104810 (2022).

Mangalam, M., Carver, N. S. & Kelty-Stephen, D. G. Global broadcasting of local fractal fluctuations in a bodywide distributed system supports perception via effortful touch. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 135, 109740, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109740 (2020).

Mangalam, M., Carver, N. S. & Kelty-Stephen, D. G. Multifractal signatures of perceptual processing on anatomical sleeves of the human body. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 17, 20200328, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2020.0328 (2020).

Rizzo, R., Garcia-Retortillo, S. & Ivanov, P. C. Dynamic networks of physiologic interactions of brain waves and rhythms in muscle activity. Human Movement Science 84, 102971, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2022.102971 (2022).

Kelty-Stephen, D. G., Lee, I. C., Carver, N. S., Newell, K. M. & Mangalam, M. Multifractal roots of suprapostural dexterity. Human Movement Science 76, 102771, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2021.102771 (2021).

Mangalam, M., Lee, I.-C., Newell, K. M. & Kelty-Stephen, D. G. Visual effort moderates postural cascade dynamics. Neuroscience Letters 742, 135511, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135511 (2021).

Riccio, G. E. & Stoffregen, T. A. Affordances as constraints on the control of stance. Human Movement Science 7, 265–300, https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-9457(88)90014-0 (1988).

Stoffregen, T. A., Smart, L. J., Bardy, B. G. & Pagulayan, R. J. Postural stabilization of looking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 25, 1641–1658, https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.25.6.1641 (1999).

Ghai, S., Ghai, I. & Effenberg, A. O. Effects of dual tasks and dual-task training on postural stability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Interventions in Aging 12, 557–577 (2017).

Fraizer, E. V. & Mitra, S. Methodological and interpretive issues in posture-cognition dual-tasking in upright stance. Gait & Posture 27, 271–279, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.04.002 (2008).

Huxhold, O., Li, S.-C., Schmiedek, F. & Lindenberger, U. Dual-tasking postural control: Aging and the effects of cognitive demand in conjunction with focus of attention. Brain Research Bulletin 69, 294–305, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.01.002 (2006).

Li, K. Z., Bherer, L., Mirelman, A., Maidan, I. & Hausdorff, J. M. Cognitive involvement in balance, gait and dual-tasking in aging: A focused review from a neuroscience of aging perspective. Frontiers in Neurology 9, 413669, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00913 (2018).

Woollacott, M. & Shumway-Cook, A. Attention and the control of posture and gait: a review of an emerging area of research. Gait & Posture 16, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6362(01)00156-4 (2002).

Andersson, G., Hagman, J., Talianzadeh, R., Svedberg, A. & Larsen, H. C. Effect of cognitive load on postural control. Brain Research Bulletin 58, 135–139, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-9230(02)00770-0 (2002).

Dault, M. C., Frank, J. S. & Allard, F. Influence of a visuo-spatial, verbal and central executive working memory task on postural control. Gait & Posture 14, 110–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6362(01)00113-8 (2001).

Dault, M. C., Geurts, A. C., Mulder, T. W. & Duysens, J. Postural control and cognitive task performance in healthy participants while balancing on different support-surface configurations. Gait & Posture 14, 248–255, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6362(01)00130-8 (2001).

Vuillerme, N., Nougier, V. & Teasdale, N. Effects of a reaction time task on postural control in humans. Neuroscience Letters 291, 77–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01374-4 (2000).

Mitra, S. Postural costs of suprapostural task load. Human Movement Science 22, 253–270, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9457(03)00052-6 (2003).

Morris, M., Iansek, R., Smithson, F. & Huxham, F. Postural instability in Parkinson’s disease: A comparison with and without a concurrent task. Gait & Posture 12, 205–216, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6362(00)00076-X (2000).

Maylor, E. A. & Wing, A. M. Age differences in postural stability are increased by additional cognitive demands. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 51, P143–P154, https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/51B.3.P143 (1996).

McNevin, N. H. & Wulf, G. Attentional focus on supra-postural tasks affects postural control. Human Movement Science 21, 187–202, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9457(02)00095-7 (2002).

McNevin, N., Weir, P. & Quinn, T. Effects of attentional focus and age on suprapostural task performance and postural control. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 84, 96–103, https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2013.762321 (2013).

Pellecchia, G. L. Postural sway increases with attentional demands of concurrent cognitive task. Gait & Posture 18, 29–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6362(02)00138-8 (2003).

Vuillerme, N. & Nafati, G. How attentional focus on body sway affects postural control during quiet standing. Psychological Research 71, 192–200, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-005-0018-2 (2007).

Campoi, E. G., Campoi, H. G. & Moraes, R. The effects of age and postural constraints on prehension. Experimental Brain Research 241, 1847–1859, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-023-06647-0 (2023).

Stamenkovic, A., Stapley, P. J., Robins, R. & Hollands, M. A. Do postural constraints affect eye, head, and arm coordination? Journal of Neurophysiology 120, 2066–2082, https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00200.2018 (2018).

Yeomans, M., Yan, S., Hondzinski, J. M. & Dalecki, M. Eye-hand decoupling decreases visually guided reaching independently of posture but reduces sway while standing: Evidence for supra-postural control. Neuroscience Letters 752, 135833, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2021.135833 (2021).

Menant, J. C., Schoene, D., Sarofim, M. & Lord, S. R. Single and dual task tests of gait speed are equivalent in the prediction of falls in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews 16, 83–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2014.06.001 (2014).

Muir-Hunter, S. & Wittwer, J. Dual-task testing to predict falls in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. Physiotherapy 102, 29–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2015.04.011 (2016).

Taylor, M. E., Delbaere, K., Mikolaizak, A. S., Lord, S. R. & Close, J. C. Gait parameter risk factors for falls under simple and dual task conditions in cognitively impaired older people. Gait & Posture 37, 126–130, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.06.024 (2013).

Tong, Y. et al. Use of dual-task timed-up-and-go tests for predicting falls in physically active, community-dwelling older adults–A prospective study. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity 1, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2022-0341 (2023).

Cortis, C., Pesce, C. & Capranica, L. Inter-limb coordination dynamics: Effects of visual constraints and age. Kinesiology 50, 133–139 (2018).

Fujiyama, H., Garry, M. I., Levin, O., Swinnen, S. P. & Summers, J. J. Age-related differences in inhibitory processes during interlimb coordination. Brain Research 1262, 38–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2009.01.023 (2009).

Fujiyama, H., Hinder, M. R., Schmidt, M. W., Garry, M. I. & Summers, J. J. Age-related differences in corticospinal excitability and inhibition during coordination of upper and lower limbs. Neurobiology of Aging 33, 1484.e1–1484.e14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.12.019 (2012).

Guan, J. & Wade, M. G. The effect of aging on adaptive eye-hand coordination. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 55, P151–P162, https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/55.3.P151 (2000).

Ruff, R. M. & Parker, S. B. Gender-and age-specific changes in motor speed and eye-hand coordination in adults: Normative values for the Finger Tapping and Grooved Pegboard Tests. Perceptual and Motor Skills 76, 1219–1230, https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1993.76.3c.1219 (1993).

Van Halewyck, F. et al. Both age and physical activity level impact on eye-hand coordination. Human Movement Science 36, 80–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2014.05.005 (2014).

Kahya, M. et al. Brain activity during dual task gait and balance in aging and age-related neurodegenerative conditions: A systematic review. Experimental Gerontology 128, 110756 (2019).

Kahya, M. et al. Brain activity during dual-task standing in older adults. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation 19, 123, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-022-01095-3 (2022).

Glisky, E. L. Changes in cognitive function in human aging. In Glisky, E. L. & Riddle, D. R. (eds.) Brain Aging, 3–20 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2007). PMID: 21204355.

Soldan, A. et al. Cognitive reserve and long-term change in cognition in aging and preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging 60, 164–172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.09.002 (2017).

Beauchet, O. et al. Stops walking when talking: A predictor of falls in older adults? European Journal of Neurology 16, 786–795, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02612.x (2009).

Li, F. & Harmer, P. Prevalence of falls, physical performance, and dual-task cost while walking in older adults at high risk of falling with and without cognitive impairment. Clinical Interventions in Aging 15, 945–952, https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.s254764 (2020).

Bekkers, E. M. et al. The impact of dual-tasking on postural stability in people with Parkinson’s disease with and without freezing of gait. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair 32, 166–174, https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968318761121 (2018).

de Souza Fortaleza, A. C. et al. Dual task interference on postural sway, postural transitions and gait in people with Parkinson’s disease and freezing of gait. Gait & Posture 56, 76–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.05.006 (2017).

Holmes, J. et al. Dual-task interference: The effects of verbal cognitive tasks on upright postural stability in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Disease 2010, 696492, https://doi.org/10.4061/2010/696492 (2010).

Mishra, R. K. et al. Evaluation of motor and cognitive performance in people with Parkinson’s disease using instrumented Trail-Making Test. Gerontology 68, 234–240, https://doi.org/10.1159/000515940 (2022).

Bisson, E., Contant, B., Sveistrup, H. & Lajoie, Y. Functional balance and dual-task reaction times in older adults are improved by virtual reality and biofeedback training. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 10, 16–23, https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9997 (2007).

Silsupadol, P., Siu, K.-C., Shumway-Cook, A. & Woollacott, M. H. Training of balance under single-and dual-task conditions in older adults with balance impairment. Physical Therapy 86, 269–281, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/86.2.269 (2006).

You, J. H. et al. Effects of dual-task cognitive-gait intervention on memory and gait dynamics in older adults with a history of falls: A preliminary investigation. NeuroRehabilitation 24, 193–198, https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-2009-0468 (2009).

Levin, S., de Solórzano, S. L. & Scarr, G. The significance of closed kinematic chains to biological movement and dynamic stability. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 21, 664–672, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2017.03.012 (2017).

Scarr, G., Blyum, L., Levin, S. M. & de Solórzano, S. L. Moving beyond Vesalius: Why anatomy needs a mapping update. Medical Hypotheses 183, 111257, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2023.111257 (2024).

Priplata, A. A., Niemi, J. B., Harry, J. D., Lipsitz, L. A. & Collins, J. J. Vibrating insoles and balance control in elderly people. Lancet 362, 1123–1124, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14470-4 (2003).

Santos, D. A. & Duarte, M. A public data set of human balance evaluations. PeerJ 4, e2648, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2648 (2016).

dos Santos, D. A., Fukuchi, C. A., Fukuchi, R. K. & Duarte, M. A data set with kinematic and ground reaction forces of human balance. PeerJ 5, e3626, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3626 (2017).

Sbrollini, A., Agostini, V., Cavallini, C., Burattini, L. & Knaflitz, M. Postural data from Stargardt’s syndrome patients. Data in Brief 30, 105452, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.105452 (2020).

de Oliveira, C. E. N. et al. A public data set with ground reaction forces of human balance in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in Neuroscience 16, 538, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.865882 (2022).

Kristianslund, E., Krosshaug, T., Mok, K.-M., McLean, S. & van den Bogert, A. J. Expressing the joint moments of drop jumps and sidestep cutting in different reference frames–does it matter? Journal of Biomechanics 47, 193–199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.09.016 (2014).

Deligiannis, T. et al. Selective engagement of long-latency reflexes in postural control through wobble board training. Scientific Reports 14, 31819, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83101-3 (2024).