Abstract

This dataset provides demographic (age and sex), psychometric, and physiological data from 28 participants (20 males, 8 females) aged 19–27 years. Psychometric assessments include four questionnaires: the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, Self-Assessment Manikin, and two perception-related scales (EmFacs and Uncanny Valley). Physiological signals recorded include electroencephalography, blood volume pulse, galvanic skin response, and skin temperature. Emotion induction was conducted using two virtual environments designed to elicit distinct emotional states: happiness (an outdoor natural forest) and anger (a subway car), with emotional stimuli delivered through speech by a digital human. Physiological responses were recorded at baseline and during immersion in the virtual environments. This dataset can support research on affective computing, human-computer interaction, and emotion recognition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Human beings are inherently social creatures, and emotions play a fundamental role in shaping behavior, decision-making, and interactions with the environment. Emotions influence cognitive processes and are closely linked to psychological and physiological responses, impacting both mental and physical well-being1.

In recent years, Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a powerful tool for simulating realistic environments and controlling sensory stimuli to study human emotions. Virtual Environments (VEs) provide researchers with a controlled setting where emotional responses can be elicited through carefully designed scenarios. Studies have demonstrated that VR can induce distinct emotional states by manipulating environmental factors such as sound, object placement, ambient lighting, and spatial design2,3,4,5,6. The ability of VR to evoke psychological and physiological changes makes it a valuable technology for studying Emotion Regulation (ER), which refers to the cognitive and behavioral processes involved in modulating emotional experiences7. ER is a key determinant of psychological resilience and is associated with various mental and physical health outcomes8,9.

A key innovation of this study is the integration of a Virtual Human (VH) as the primary means of emotion induction. While previous research has explored VR for emotion elicitation10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17, the present study uniquely focuses on stimulating empathy through the dialogue and body language of a VH. As human-computer interaction advances, the development of realistic and emotionally expressive artificial agents has become crucial for creating immersive and engaging virtual experiences. The selected VEs were designed to favor the induction of specific emotions—happiness in a natural outdoor forest and anger in a subway car—enhancing the effectiveness of emotion elicitation through environmental context.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have specifically investigated the combined effect of VH dialogue and body language within a VR setting for emotion induction. This study introduces a publicly available dataset that includes demographic, psychometric, and physiological data from 28 participants (20 males, 8 females) aged 19–27 years. Physiological signals recorded include Electroencephalography (EEG), Blood Volume Pulse (BVP), Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), and Skin Temperature (TMP).

Methods

All participants provided informed consent according to the World Association Declaration of Helsinki before the experiment, following ethical guidelines approved by the Ethical Committee of Tecnologico de Monterrey, number: P000369-DN-RespElectroCI-CR005.

Participants were recruited based on specific inclusion criteria: individuals with no history of neurological disorders, vertigo, emotional disturbances, head trauma, psychological disorders, or the use of medication for psychological conditions. Additionally, all participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

Virtual reality design

The Virtual Environments VEs were designed to elicit two distinct emotions: happiness and anger. These emotions were selected based on their opposing valence (positive for happiness, negative for anger), while maintaining a similar level of high arousal, as shown in Fig. 1. The choice of environments was informed by previous research on the influence of environmental factors on emotional responses.

The two-dimensional circumplex emotional model based on35.

To induce happiness, a natural outdoor forest setting was created, see Fig. 2a, as studies have shown that environments with natural elements tend to evoke greater pleasure and interest18,19,20. Conversely, to elicit anger, a subway car environment was designed in Fig. 2b, given that public transportation in Mexico is often associated with stressful and controversial situations21. Additionally, lighting conditions were adjusted based on color psychology; the natural setting was brightly illuminated, while the subway environment had dim lighting, as higher color saturation has been linked to more positive emotional valence22.

Design of the VEs used during the experiment. (a) Subway car. (b) Natural forest. (c) Body and face of the VH used in VEs. The selected VEs were created and modified in Unreal Engine36.

A VH was integrated into both environments to facilitate emotion induction through empathy, it is depicted in Fig. 2c. As social beings, humans tend to relate to and be influenced by others’ emotional expressions. The VH was designed with naturalistic body movements, facial expressions, and speech to enhance emotional contagion. The VH’s animation was created using the body movements and voice of a theater actress, ensuring expressive and realistic gestures.

Body language was tailored to each emotional state:

-

Happiness expression: Open arms and legs, dynamic arm movements, and an overall relaxed posture.

-

Anger expression: Extended body posture, hands on the waist, clenched fists, raised arms, and crossed arms—consistent with established emotion expression models23.

For facial expressions, the VH exhibited movements aligned with emotion prototypes24:

-

Happiness: A Duchenne smile, characterized by raised cheeks and crow’s feet around the eyes.

-

Anger: Furrowed eyebrows, widened eyes, tightened lips, and an open mouth.

The VH’s speech was carefully designed to match the intended emotional expression. Speech parameters such as intonation, duration, intensity, and fundamental frequency were adjusted based on established acoustic features of emotions25. For instance, anger is typically associated with a higher fundamental frequency, while happiness has variable arousal-dependent vocal characteristics.

In both scenarios, the VH delivered scripted dialogues:

-

Natural environment (happiness induction): The VH expressed admiration for the landscape, describing feelings of joy and peace, and shared a positive family-related memory, ultimately encouraging the participant to engage in similar experiences.

-

Subway environment (anger induction): The VH recounted a personal experience in public transportation, highlighting injustices and discomforts, aiming to evoke frustration and empathy from the participants.

To record the VH’s body and facial movements, a professional theater actress was recruited. Her performance was captured using a Vicon motion capture system for full-body gestures and Face ware for high-fidelity facial expression tracking. This ensured that the VH conveyed natural, emotionally congruent movements and expressions aligned with the intended emotional states.

The speech recordings were also performed by the same actress in a controlled studio setting, ensuring consistency in intonation, duration, and intensity across both emotional conditions. Each speech segment lasted approximately 90 seconds within a 3-minute virtual exposure, leaving time for transitions and ambient environmental cues.

Both virtual environments and the VH animations were developed and integrated using Unreal Engine 524, offering high quality rendering and immersive interaction. Lighting conditions, textures, ambient sounds, and environmental details were carefully adjusted to reinforce the emotional intent of each scenario. Additionally, the HTC VIVE Pro 2 virtual reality system was used to display the VEs in an immersive, room-scale VR setting. The system included SteamVR base stations for tracking, hand controllers for interaction within the virtual environment, and a head-mounted display to visually isolate participants from external stimuli.

Speech onset and offset within the virtual scenarios were synchronized with EEG data collection via trigger codes sent from Unreal Engine to the Unicorn Hybrid Black EEG system, ensuring accurate alignment between neural data and stimulus presentation. A schematic timeline of the experimental procedure and VR exposure sequence is presented in Fig. 6.

Material and equipment

The VEs were designed and implemented using Unreal Engine. The HTC VIVE Pro 2 virtual reality system was used for immersion, comprising:

-

Tracking base stations to define the interaction area.

-

VR headset to render the virtual environment.

-

Handheld controllers for participant interaction, including questionnaire responses.

For EEG recording, a wireless Unicorn Hybrid Black headset was used, equipped with eight active electrodes placed according to the international 10–20 system at positions Fz, C3, Cz, C4, Pz, PO7, PO8, and Oz (see Fig. 3) Signals were sampled at 250 Hz with a bandwidth range of 0.1–60 Hz. The reference and ground electrodes were positioned on the left and right mastoids using disposable adhesive electrodes. Prior to data collection, electrode impedance was verified to be below 10 kΩ for all channels, following manufacturer recommendations. Electrode gel was applied as needed to improve scalp contact and minimize impedance values. Signal quality was assessed visually through the Unicorn Suite Hybrid Black application, and adjustments were made until optimal signal acquisition conditions were achieved.

Physiological data BVP Sampled at 64 Hz, GSR, and skin TMP were sampled at 4 Hz and recorded using the Empatica E4 wristband, worn on the participant’s non-dominant wrist (typically left wrist, unless otherwise requested by the participant). The device’s photoplethysmographic sensor, GSR electrodes, and infrared thermopile are integrated into a fixed wristband design, with sensor positions standardized according to the manufacturer’s specifications. As the E4 device is a commercial wearable, precise sensor positioning relative to anatomical landmarks was ensured by fastening the device approximately 1.5 cm proximally to the radial styloid process of the wrist, ensuring firm but comfortable contact. No conductive gel was required for the E4 sensors, as the device uses dry electrodes and photoplethysmographic sensors built into its housing.

Psychometric Assessments. To evaluate participants’ ER strategies, the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) was administered. The ERQ is a 10-item self-report scale designed to assess the habitual use of two common ER strategies: (1) Cognitive Reappraisal – modifying the interpretation of an emotional event and (2) Expressive Suppression – inhibiting outward emotional expressions. The ERQ is widely recognized for its validity and reliability across diverse populations and clinical settings26.

Affective Responses to Virtual Environments. The Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) questionnaire was used to measure participants’ affective responses to the VEs. The SAM assesses three emotional dimensions: (1) Pleasure (valence), (2) Arousal and (3) Dominance. Each dimension was rated on a 9-point Likert scale (1 = lowest, 9 = highest)27.

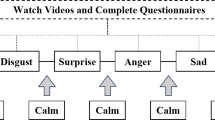

Perception of the Virtual Human (VH). Two additional questionnaires were administered to assess participants’ perception of VH’s emotional expressions and realism:

-

1.

Emotion Facial Action Coding System (EmFacs) Questionnaire – Participants identified the VH’s expressed emotion from seven predefined categories: fear, anger, joy, sadness, disgust, surprise, and neutral.

-

2.

Uncanny Valley Perception Questionnaire – Adapted from McDonnell et al.28, this questionnaire evaluated participants’ perception of the VH’s realism, appeal, familiarity, friendliness, and trustworthiness. Responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = lowest, 7 = highest).

Experimental procedure

The experiment was conducted in a well-equipped laboratory, it can be seen on Fig. 4a, ensuring optimal conditions for setting up the VR equipment, accommodating participants, and recording Electroencephalography (EEG) data. The procedure followed these steps, and it is shown on Fig. 6:

-

1.

Questionnaire Administration: Participants first completed the ERQ.

-

2.

Preparation and Instructions: Participants were seated in a chair to minimize fatigue and reduce EEG signal artifacts. While the EEG and VR equipment were fitted see Fig. 4b, they received standardized instructions, which lasted approximately 10 minutes.

-

3.

Baseline Recording: To record their initial resting-state EEG activity, participants fixated on a white cross against a black VE for 2 minutes, see Fig. 5a.

-

4.

Exposure to VE: Participants were immersed in a subway scene for 3 minutes, see Fig. 5b. Subsequently, they were transitioned to a scene where they completed a set of questionnaires, a process lasting no more than 3 minutes, it is shown on Fig. 5d.

-

5.

Rest Period: A 2-minute break was provided.

-

6.

Second Experimental Phase: The procedure was repeated, with the only modification being the replacement of the subway scene with a nature scene see Fig. 5c, also for 3 minutes.

(a) The laboratory setup selected for conducting the experiment. (b) The Unicorn Hybrid Black system used for EEG monitoring, the E4 wristband for physiological data acquisition, and the HTC VIVE Pro 2 headset worn by a participant during the experiment. The participant consents to appear in the figure.

Virtual environments used in the experimental procedure. The procedure consisted of four steps: (a) baseline recording for each participant, (b) immersion in a virtual environment designed to induce anger (subway scene), (c) immersion in a virtual environment designed to induce happiness (nature scene), and (d) completion of a psychological response report based on the SAM questionnaire.

Data analysis

Five EEG recordings were discarded due to excessive noise and irreparable corruption (participants 1–3, 8, 25). EEG signals were preprocessed using the EEGLAB toolbox29 for MATLAB. Initially, the EEG signals were band-passed with a high-pass filter at 1 Hz and a low-pass filter at 60 Hz, employing a finite impulse response filter to attenuate slow drifts and high-frequency noise. Following this, automated artifact rejection was conducted through the Clean Rawdata plugin30, applying the default parameters established by the tool. Specifically, flatline channels were identified and removed if no signal was detected for more than 5 seconds, while channels with a correlation below 0.8 with neighboring channels were also discarded. Segments presenting line noise exceeding 4 standard deviations and channels containing over 20% of bad segments were rejected to ensure data integrity.

After this initial cleaning, Independent Component Analysis (ICA) was performed to decompose the EEG data into independent components, which allowed for the identification of artifact-related activity. The ICLabel plugin31 was then utilized to automatically classify each component into categories such as brain, muscle, eye, heart, line noise, channel noise, and other artifacts. Components classified as non-brain sources with a probability greater than 80% were flagged, manually reviewed, and subsequently removed to minimize contamination from ocular, cardiac, muscular, and environmental artifacts. The EEG data were then re-referenced to the common average reference before being subjected to further statistical analysis.

Physiological and behavioral data exported in CSV format, including data from the E4 device and self-report measures, were processed using Microsoft Excel 365. Data preparation involved computing descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviations, as well as performing participant-level completeness checks to identify and exclude datasets with missing or inconsistent entries. All calculations and criteria for data exclusion were conducted through standard Excel functions and conditional formulas without the use of custom MATLAB or Python scripts.

Data Records

The dataset has been organized to maintain the structure presented in Fig. 7. The dataset is publicly available at Mendeley Data32 https://doi.org/10.17632/y76vbw92y9.3. Researchers can leverage this dataset for machine learning model training, emotion classification, and validation studies in affective computing and immersive environment research.

Data files

Participant demographic and psychometric data are provided in an Excel file (Data.xlsx), which contains three sheets: (1) Outcomes: Each row represents one participant, with data organized sequentially from left to right. The file is structured by the two main virtual environments, with column headers corresponding to the applied questionnaires. (2) ERQ_Categories: Defines the two emotion regulation strategies considered in the ERQ. (3) QuestionnaireRanges: Specifies the ranges and interpretations of the applied questionnaires. EEG data are provided in SET format, and physiological signals (BVP, GSR, TMP) recorded with the E4 device are provided in CSV format. Both file types can be imported using MATLAB’s open-source toolbox, EEGLAB.

The root directory of the dataset contains an Excel file (as previously described) and two main folders: E4 and EEG, see Fig. 7.

E4 Folder

This folder contains physiological data acquired using the E4 wristband. It is organized into two main subcategories: Nature and Subway. Within each subcategory, there are three folders: BVP, GSR, and TMP, corresponding to the respective physiological signals. As the E4 recordings were continuous, transitions from the baseline state to the VE are marked with events.

EEG Folder

Similar to the E4 folder, the EEG folder is divided into Nature and Subway categories. These are further divided into three subgroups: Baseline, Pre-processing, and Raw.

The Pre-processing and Raw folders contain EEG data acquired during exposure to the virtual environment. Data in the Pre-processing folder has undergone preprocessing steps, while the Raw folder contains unprocessed EEG data.

The Baseline folder contains EEG data recorded during the baseline state of participants, which may be either preprocessed or raw, depending on the specific folder.

Technical Validation

The selection of VEs and key features of VH, including speech and movement, was informed by prior research. Prototypes and pilot trials were conducted to optimize the final design of the VE, see Fig. 8a. The experimental space was meticulously prepared and tested to ensure ideal conditions for data collection, see Fig. 8b, and preliminary checks on the installed equipment were performed before the experiment began.

(a) Set-up made for the audio and motion recording of the VH integrated into the VEs. The recording was performed with motion capture systems from Vicon37 and Faceware38. (b) Participant in the laboratory selected for the experiment. The participant was equipped with the VR Head-Mounted Display, as well as the wireless EEG-headset Unicorn Hybrid Black and the E4 wristband for physiological signal acquisition. The participants consent to appear in the figure.

The tracking system for this study was developed in the following stages: (1) demographic data collection, (2) administration of the ERQ, (3) monitoring of EEG and physiological signals, and (4) completion of the SAM and perception questionnaires. Participant age and gender distributions are shown on Fig. 9.

To assess the quality of the raw signals in the dataset, Automagic’s open-source, standardized quality assessment tool was used33. This tool provides objective measures of data quality based on indicators such as the ratio of identified bad and interpolated channels and quality metrics based on voltage amplitude magnitudes, including the overall high amplitude, time points of high variance, and channels with high variance. The data were categorized into three quality levels: “Good” (very clean EEG data), “OK” (noisier data), and “Bad” (data with high noise levels). Table 1 presents the categorization results for raw signals from both VEs, both at baseline and during interaction with the VH.

ICA was performed to evaluate the average percentage of brain activity in the EEG signals. ICA seeks to identify statistically independent sources of signal (brain, muscle, eye, heart, line noise, and channel noise), allowing for the separation of non-brain artifacts from the original signal.

Table 2 displays the mean percentage of brain activity for each channel in both raw and preprocessed EEG data, organized by the two VEs used in the experiment. The lower section of the table presents the overall average percentages, demonstrating the technical validity of the EEG signals in this dataset for research purposes.

The ERQ, a 10-item questionnaire with robust psychometric properties, was used to assess participants’ emotion regulation strategies. It has demonstrated structural validity across diverse participant groups and clinical settings26, making it a reliable tool for evaluating individual emotion regulation strategies.

The SAM, an image-based tool devised by Bradley27, was used to assess participants’ pleasure, arousal, and dominance in response to the VEs. The SAM is brief, graphic, and effective for measuring emotional responses in various contexts34. Figure 10 presents the average emotional responses obtained from participants using the SAM.

Additionally, participants’ perceptions of the VH were evaluated using a questionnaire that assessed realism, appeal, familiarity, friendliness, and trustworthiness on a 1–7 scale, where 1 indicates the lowest and 7 indicates the highest rating. This questionnaire was adapted from measures used by McDonnell et al.28. Figure 11 shows the average ratings from this perception questionnaire.

The fixed order of scene presentation may introduce order effects, such as carryover emotions or habituation, which could confound the comparison between anger and happiness induction. While this design ensures consistency, future studies should counterbalance conditions to disentangle scene-specific effects from sequence biases.

Code availability

EEG signals were preprocessed in the EEGLAB toolbox29 for MATLAB, downloadable at https://sccn.ucsd.edu/eeglab/.

References

Leary, M. R. Emotional responses to interpersonal rejection. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 17, 435–441, https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.4/mleary PMID: 26869844 (2015).

Marín-Morales, J. et al. Affective computing in virtual reality: emotion recognition from brain and heartbeat dynamics using wearable sensors. Sci. reports 8, 1–15 (2018).

Hortensius, R., Hekele, F. & Cross, E. S. The perception of emotion in artificial agents. IEEE Transactions on Cogn. Dev. Syst. 10, 852–864, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCDS.2018.2826921 (2018).

Montana, J. I. et al. The benefits of emotion regulation interventions in virtual reality for the improvement of wellbeing in adults and older adults: A systematic review. J. Clin. Medicine 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020500 (2020).

Zheng, L., Mountstephens, J. & Teo, J. Four-class emotion classification in virtual reality using pupillometry. J. Big Data 7, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-020-00322-9 (2020).

Liao, D., Huang, Y., Tan, Z., Yang, J. & Xu, X. Design of virtual reality scenes with variable levels of fear evocation. In Chen, J. Y. & Fragomeni, G. (eds.) Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality: Applications in Health, Cultural Heritage, and Industry, 103–115 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018).

Developing emotional regulation skills in the workplace. A key to job satisfaction among social conflicts between colleagues. Hum. Resour. Manag. Int. Dig. 26, 19–21 (2018).

Hooker, S. A., Masters, K. S. & Park, C. L. A meaningful life is a healthy life: A conceptual model linking meaning and meaning salience to health. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 22, 11–24 (2018).

Cloitre, M. et al. Emotion regulation mediates the relationship between ages and physical and mental health. Psychol. Trauma: Theory, Res. Pract. Policy 11, 82 (2019).

Tsai, C.-F. et al. The effect of augmented reality and virtual reality on inducing anxiety for exposure therapy: a comparison using heart rate variability. J. Healthc. Eng. 2018 (2018).

Marín-Morales, J. et al. Affective computing in virtual reality: emotion recognition from brain and heartbeat dynamics using wearable sensors. Sci. reports 8, 13657 (2018).

Kisker, J., Gruber, T. & Schöne, B. Behavioral realism and lifelike psychophysiological responses in virtual reality by the example of a height exposure. Psychol. research 85, 68–81 (2021).

Gromer, D., Reinke, M., Christner, I. & Pauli, P. Causal interactive links between presence and fear in virtual reality height exposure. Front. psychology 10, 141 (2019).

Lin, J., Cao, L. & Li, N. Assessing the influence of repeated exposures and mental stress on human wayfinding performance in indoor environments using virtual reality technology. Adv. Eng. Informatics 39, 53–61 (2019).

Schweizer, T., Renner, F., Sun, D., Becker-Asano, C. & Tuschen-Caffier, B. Cognitive processing and regulation modulates analogue trauma symptoms in a virtual reality paradigm. Cogn. therapy research 43, 199–213 (2019).

Kim, Y., Moon, J., Sung, N.-J. & Hong, M. Correlation between selected gait variables and emotion using virtual reality. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 1–8 (2019).

Takac, M. et al. Public speaking anxiety decreases within repeated virtual reality training sessions. PloS one 14, e0216288 (2019).

Martínez-Soto, J. & González-Santos, L. Affective psychological restoration through mediated exposure to the environment (restauración psicológica afectiva a partir de la exposición mediada del ambiente). PsyEcology 11, 289–318, https://doi.org/10.1080/21711976.2020.1730133 (2020).

Knez, I. et al. Before and after a natural disaster: Disruption in emotion component of place-identity and wellbeing. J. Environ. Psychol. 55, 11–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.11.002 (2018).

Kuwano, S., Namba, S., Hayashi, Y., Komatsu, M. & Kato, T. Auditory and visual interaction in the aesthetic evaluation of environment. Empir. Stud. Arts 19, 191–200, https://doi.org/10.2190/MDF0-1CNE-Y4UW-VNQN (2001).

Murata, M., Delgado Campos, J. & Suárez Lastra, M. Why the people don’t use the subway? the impact of the transportation system on mexico city´ s structure. Investig. geográficas 0 (2017).

Geslin, E., Jégou, L. & Beaudoin, D. How color properties can be used to elicit emotions in video games. Int. J. Comput. Games Technol. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5182768 (2016).

Noroozi, F. et al. Survey on Emotional Body Gesture Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Affect. Comput. 12, 505–523, https://doi.org/10.1109/TAFFC.2018.2874986 (2021).

Barrett, L. F., Adolphs, R., Marsella, S., Martinez, A. M. & Pollak, S. D. Emotional Expressions Reconsidered: Challenges to Inferring Emotion From Human Facial Movements. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 20, 1–68, https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100619832930 (2019).

Swain, M., Routray, A. & Kabisatpathy, P. Databases, features and classifiers for speech emotion recognition: a review. Int. J. Speech Technol. 21, 93–120, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10772-018-9491-z (2018).

Wigham, S. et al. Questionnaires used in complex trauma intervention evaluations and consideration of their utility for autistic adults with mild intellectual disability: A systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 117, 104039, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104039 (2021).

Bradley, M. M. & Lang, P. J. Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 25, 49–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9 (1994).

McDonnell, R., Breidt, M. & Bülthoff, H. H. Render me real? investigating the effect of render style on the perception of animated virtual humans. ACM Trans. Graph. 31, https://doi.org/10.1145/2185520.2185587 (2012).

Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. {EEGLAB}: {A}n open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial {EEG} dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 134, 9–21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009 (2004).

Kothe, C., Miyakoshi, M. & Delorme, A. Clean_rawdata (2019).

Pion-Tonachini, L., Kreutz-Delgado, K. & Makeig, S. Iclabel: An automated electroencephalographic independent component classifier, dataset, and website. NeuroImage 198, 181–197, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.05.026 (2019).

Ramirez-Lechuga, S., Alonso-Valerdi, L. M. & Ibarra-Zarate, D. I. Audiovirtual Reality to induce anger and happiness emotions: A physiological response (EEG, GSR, BVP and TMP) database. Mendeley Data, V3 https://doi.org/10.17632/y76vbw92y9.3 (2023).

Pedroni, A., Bahreini, A. & Langer, N. Automagic: Standardized preprocessing of big eeg data. NeuroImage 200, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.046 (2019).

Morris, J. D. Observations: Sam: the self-assessment manikin; an efficient cross-cultural measurement of emotional response. J. advertising research 35, 63–68 (1995).

Zhong, K., Qiao, T. & Zhang, L. A study of emotional communication of emoticon based on russell’s circumplex model of affect. In Marcus, A. & Wang, W. (eds.) Design, User Experience, and Usability. Design Philosophy and Theory, 577–596 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019).

Epic Games. Unreal engine.

Vicon. Award winning motion capture systems.

Faceware. Award-winning gold standard facial motion capture solutions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express my deepest gratitude to Tecnologico de Monterrey and to CONAHCYT for the financial support provided for this work. We would also like to express our sincere gratitude to Carlos Vilchis for his support and provision of the necessary materials for the development and implementation of virtual environments, as well as for his hospitality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.A., D.I. and S.R. conceived the experiment, S.R. conducted the experiment, S.R., L.A. and D.I. analyzed the results and supervised the information organization. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alonso-Valerdi, L.M., Ramirez-Lechuga, S. & Ibarra-Zarate, D.I. Audiovisual virtual reality for emotion induction: a dataset of physiological responses. Sci Data 12, 1387 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05691-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05691-5