Abstract

Soil health is the cornerstone of sustainable agriculture, but studies have shown that agricultural soils are degrading due to inadequate soil management practice adoption. To understand the status quo, we surveyed 2,728 Swiss arable farms in 2024. The dataset captures the soil management practices used alongside the decision-making surrounding their implementation in the 2022/2023 production season. Four core components are covered: (1) farm and farmer characteristics, including gender, age, experience, labour, farm size and Agri-environmental scheme participation; (2) detailed records of twelve arable soil management practices, including uptake extent, number of years used, perceived knowledge and peer adoption; (3) farmers’ priorities for soil health and their assessment of key agricultural challenges; and (4) production data for a subset of farms cultivating milling wheat, including wheat area, wheat yield and input application rates. We enriched the dataset with linked secondary plot-level census data. This combined dataset provides a comprehensive resource that enables the analysis of current farming practices, knowledge gaps and challenges to maintain and improve the health of arable soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

In this data descriptor we present data from 2,728 Swiss arable farms regarding the use of soil management practices for improving soil health on their arable land during the 2022/2023 production season1. Between December 2023 and January 2024, we collected a comprehensive dataset via an online survey from arable farms across Switzerland. The survey captured a breadth of information on farmers’ knowledge, preferences, and practices related to soil health. Additionally, this data descriptor incorporates two supplementary datasets: (1) wheat production data and (2) a secondary dataset extracted from freely available national geographic and farm census data, which further enriches the understanding of the agricultural landscape and complements the survey data1. The supplementary datasets can be linked to the main dataset through a common key variable.

Before presenting the data collection protocol and the detailed variables of the datasets, we first provide a brief introduction to soil health in European agriculture and then describe the study area and associated policy background in Switzerland at the time of our study.

Soil Health and Agriculture

Soil is an indispensable resource that is vital for the continued functioning of ecosystems as well as for ensuring the long-term supply of food2,3,4. Maintaining and improving the health of agricultural soils is critical to achieve the sustainable transformation goals set for the food system5. In addition to food production, agricultural soils provide many additional essential ecosystem services that are crucial to support life on earth2,4,6. Such services include carbon sequestration and storage functions7,8, the regulation of water quality and quantity flowing into water courses2,9 and provision of habitat for a large array of soil fauna and flora10,11,12.

Soil health is increasingly under threat from intensive agricultural practices and changing weather patterns13. This includes higher rainfall intensities, which are projected to accelerate soil erosion and result in substantial economic losses in the coming decades14,15. Consequently, improving and maintaining agricultural soil health is high on the agenda of policymakers in Switzerland, in Europe and around the globe16,17,18.

In Europe, arable farmers are encouraged to adopt beneficial soil management strategies: some of which are incentivised through Agri-environmental schemes19. Practices such as reduced tillage, organic matter addition, crop rotation and maintaining permanent soil cover are often subsidised and have been shown through field trials to improve soil health20, enhance resilience to environmental stressors21, and support the provision of soil ecosystem services22,23,24. Yet, to steer the transition towards more sustainable and healthy agricultural soils in an effective and efficient manner, it is imperative to understand the current practices adopted on farms, their impacts and the potential drivers or barriers to further implementation25,26 within their geographic and cultural context27,28. However, there is currently a significant gap in large-scale data on actual soil health decisions across different farming practices. The lack of such comprehensive data limits our ability to fully assess the effectiveness of current practices, understand farmers’ decision-making processes, and identify the key factors influencing the adoption of sustainable soil management. The dataset we present here fills an important gap by providing insights into the actual soil management practices of Swiss arable farmers, enabling a deeper understanding of the barriers and drivers that can shape future soil health initiatives.

Study Area

Swiss policy background

Switzerland launched its own national soil strategy in 2020 with eight stated targets for agriculture, including the reduction of soil compaction, prevention of soil degradation from erosion, minimising soil organic matter breakdown and avoiding soil biodiversity loss29. Swiss agriculture operates within a distinct policy framework, whereby farms are supported financially to a high degree by the Federal Government directly via direct subsidies (known as direct payments) as well as indirectly via border regulations targeting the import and export of agricultural products30,31,32.

As a prerequisite to receiving direct payments, farmers in Switzerland must provide proof of ecological performance (German name Ökologischer Leistungsnachweis), which sets out basic environmental and land management requirements. Once Swiss farmers fulfil the proof of ecological performance, which is the case for 98% of farms33, they become eligible for direct payments classified within five different pillars. It is important to note that Swiss area-based agricultural support payments are also graduated across distinct agricultural zones (Fig. 1), this is due to the diverging landscapes prevalent across Switzerland. Two of these area-based payments are the “cultural landscape” and “food security” contributions. However, farmers may also enrol voluntarily for further, mainly action-based, schemes known as “production system”, “landscape quality” and “biodiversity” contributions. These require that farmers undertake additional practices and meet additional criteria.

The Swiss Federal Office of Agriculture has two subsidy schemes within the production system contribution pillar, introduced in 2023, directly targeting soil. These include the reduced tillage scheme (CHF 250/ha enrolled) and the continuous soil cover scheme (CHF 200/ha enrolled)34. Additionally, several core concepts of sustainable soil management are a statutory minimum requirement for receiving direct payments, such as appropriately diversified crop rotations35. However, many beneficial soil management practices were not directly subsidised in Switzerland at the time of our survey.

Swiss agricultural sector

As of 2023, the Swiss farming sector comprised 47,719 farm enterprises, with each covering an average farm size of 21.84 hectares, operating under one of three production systems: conventional, integrated or organic production36,37. Conventional farming meets basic legal standards, whilst integrated production is a state-recognised system that emphasises resource efficiency, soil protection, and reduced – but not eliminated – use of synthetic pesticides and fertilisers. Within the integrated production framework, various programs exist that define different levels of input use restrictions38. Organic farming on the other hand follows stricter ecological and animal welfare standards and prohibits the use of synthetic pesticides and mineral fertilisers altogether39.

Of the total number of farms across all production systems, only 19,227 are involved in any form of grain production (40.40% of farms) and the total area of arable fields in Switzerland is 274,896.24 hectares (26.38% of all farmed land), as of 2023. Winter wheat is the most widely produced arable crop, covering 78,075.96 hectares (28.40% of the arable area) and amounting to a total inland production of 413,805 tonnes in 2023 (80.63% going to human consumption)40,41,42. A total of 148,880 people are employed in agriculture, 44.21% on a permanent basis, and 71.03% of farms are full-time enterprises based on figures from 202336.

Geographically, Switzerland can be divided into several different landscape regions: the Jura mountains to the north-west, the Swiss plateau in the centre, and the Alps in the south and east. Arable farming in Switzerland is primarily concentrated in the Swiss Plateau42. The predominant climate is highly dependent on the topography but in the Swiss plateau, there is a continental climate which is typified by cold winters and warm summers (for further information on the climate of Switzerland, see: The climate of Switzerland - MeteoSwiss). Figures 1 and 2 provide an overview of the regional diversity within Swiss agriculture: Fig. 1 above illustrates the country’s agricultural zones, while Fig. 2 below depicts its main biogeographical regions. Each biographical region is shaped by its unique geographic, climatic, and ecological conditions, as well as the agricultural practices and land use strategies adopted by farmers. In addition to these physical characteristics, Switzerland is also shaped by four distinct cultural-linguistic regions—German, French, Italian, and Romansh. The borders of these language regions are indicated in Fig. 2.

Methods

Sampling procedure

In the context of the Horizon Europe Project “InBestSoil”, the data collection focused on arable management practices in Switzerland. Specifically, those practices related to soil health and soil conservation undertaken within the 2022/2023 production season. Farm selection for the survey was based on specific criteria to ensure that the data collection accurately represented arable agricultural practices in Switzerland. These criteria were designed to target farms that were significantly involved in arable agriculture, which is crucial for assessing arable soil health management practices. Eligible farms were required to meet the following criteria:

-

Grow wheat in the preceding season (2021/2022).

-

Farm at least 3 hectares of arable land in the preceding season (2021/2022).

-

Arable land must have comprised at least 20% of the total farmed area in the preceding season (2021/2022).

We entered a data sharing agreement with the Federal Office of Agriculture to enable our survey campaign via access to contact information of all farmers who met the above selection criterion (see the supplementary material in the data repository for a copy of this contract)1. The Federal Office of Agriculture implemented our selection criterion on the agricultural data that they collect on a yearly basis from the direct payment applications of all Swiss farmers. Note, at the time of our application to the Federal Office of Agriculture, data for the production season 2022/2023 was not available. This is why we use data from the preceding production season for specifying the selection criteria, as this was the latest data available at the time, from which the Federal Office of Agriculture could make an assessment of which farm contact details to share with us for the survey.

In August 2023, we received the contact details of 15,023 farmers who qualified for the survey from the Federal Office of Agriculture’s records. The information we received included the email address, farm identification number, language spoken, name and form of address. However, as per our data sharing agreement with the Federal Office of Agriculture, this data was allowed exclusively for our use in this project and cannot be shared with any outside partner not party to the aforementioned data sharing contract. The contact data of farmers that was received from the Federal Office of Agriculture will be kept for the duration of the InBestSoil project and stored securely on private institutional servers in encrypted files. All contact information will be deleted at the conclusion of the project (December 2026) and all data presented herewith is strictly anonymised to protect the data and identities of the farmers who took part in the survey. Moreover, we have taken measures to prevent any farmers from being identified via their answers (for example variables such as manager age, wheat areas grown, location etc. have been classified into more homogenous categorical groups), which means that the data we present here is slightly different to the data that we have available for our own analyses, as agreed under the data sharing agreement with the Federal Office of Agriculture.

Survey design and content

While adoption of agricultural practices certainly varies with farm characteristics such as size, labour availability, or participation in agri-environmental schemes, these factors alone are not sufficient to explain farmer behaviour. There is no single set of drivers that consistently predicts adoption across studies or regions43. Instead, adoption depends strongly on local contexts, and the interplay of economic, social, and psychological factors44. To capture the complexity of adoption behaviour, the survey included questions on farmers’ priorities, perceptions, self-assessed competencies, and personal goals, as well as their exposure to peer practices, participation in training and advisory services, and sources of information. These dimensions are important because farmers do not make decisions in isolation; their attitudes towards risk, innovation and environmental values can influence their decisions alongside financial considerations. Such data contribute to a more thorough understanding of the multifaceted factors influencing soil health-related decisions. The inclusion of these variables also offer valuable insights into the barriers and drivers of sustainable soil management, essential for shaping targeted and effective agricultural policies and support programs.

The full survey is available within the data repository in French, German and English1. The final survey was developed over the course of a year, including revisions resulting from three rounds of consultation with external stakeholders, internal consultation and testing with farmers. All participants in the survey were asked to give their informed consent by ticking a box in the online questionnaire, confirming their agreement to participate in the study. Additionally, participants consented to the linking of secondary geographical data with their responses, which was also confirmed by ticking a separate checkbox in the survey. Once the participants had agreed to these, the survey was administered uniformly following the structure outlined below. All questions appeared in the same order and, only if certain exclusion criteria were met – such as when their previous answer ruled out any further sub-questions - were some sub-questions hidden from the view of participants. Inclusive of all sub-questions, the survey contained 57 questions, and answering the questionnaire took farmers a median time of 23 minutes.

The survey design was based on previously implemented surveys regarding agricultural production practices in Switzerland45,46,47,48,49. Specifically, questions on farm information and participation in soil-related programmes were included to assess farmers’ engagement with policy incentives and voluntary schemes. The inclusion of personal characteristics aimed to understand demographic drivers of management behaviour. The questions on management practices were developed in close collaboration with experts from the soil science and agricultural extension fields, and were cross-checked with relevant literature. Data on milling wheat production and related input use were collected to link agronomic decisions with productivity outcomes. Information on structural farm characteristics, such as farm type, location, and land tenure, provides context for understanding the decision-making environment and potential constraints faced by farmers. Finally, a strong focus was placed on behavioural and attitudinal factors, including information sourcing, perceived risks, and personal goals, to account for the cognitive and motivational dimensions of farmer behaviour. The following section provides an overview of the variables investigated within each of these question groups. The collected data are documented in the accompanying datasets1. Each question group corresponds to a clearly defined set of columns.

Demographic details (Primary dataset columns B-H)

Age, duration farm responsibility, gender, full time equivalent and whether the farm succession is already secured.

Participation in soil health programmes (Primary dataset columns H-S)

Organic farming support, soil cover scheme, reduced tillage scheme, herbicide-free farming scheme, pesticide-free farming scheme, efficient fertiliser use, wider row planting, beneficial insect strip, precision application, cantonal soil health support, cantonal input reduction support, cantonal investment and equipment support.

Management Practices (Primary dataset columns T-CA)

An overview of all management practices addressed in the survey, including their descriptions and the typical machinery used, is provided in Table 1. Farmers were asked about their knowledge about the practices, the application as well as the frequency of application within the last 10 years and whether they know other farmers that use the practice. The practices covered by our survey were selected based on the input of soil scientists and agricultural extension workers based in Switzerland.

Milling Wheat Production (Wheat dataset columns B-M)

Production standard, hectares of milling wheat grown, yield milling wheat, yield milling wheat over last five seasons, quantity synthetic fertiliser, quantity organic fertiliser, sowing density, number of biostimulant treatments, number of herbicide treatments, number of fungicide treatments, number of insecticide treatments and number of plant growth regulator treatments.

Structural Farm Characteristics (Primary dataset columns CD-CP)

Family members employed, farm focus (arable, livestock, permanent crop, others), full time or part-time farm, percentage of rented land, whether the soil has been assessed and a soil management plan exists.

Training and Advice (Primary dataset columns CQ-CZ)

Advice agricultural adviser, advice agricultural retailer, advice cantonal or national institution, consult other farmers, consult social media channels, consult publications or webpages, participation equipment demonstration, participation farmer discussion or training group, participation farm demonstration, participation course.

Behavioural and Attitudinal Factors (Primary dataset columns DA-EK)

Respondents’ self-assessment of their perceived influence of the weather on crop production and ambitiousness of self-set production goals.

Respondents’ self-assessment of their willingness to take risks in the domains of; agricultural production, investment in agricultural technology and crop protection.

Respondents’ self-assessment of their confidence in being able to; find solutions to arable production challenges and achieve production goals by harvest end.

The respondents self-reported importance of the following aspects in decision making;

Maximising yields, minimising input costs, minimising time or labour requirements, minimising production risks, minimising farm exposure to weeds or pests or diseases, adapting to weather patterns, adapting to farmland conditions, improving soil health or structure or fertility, improving biodiversity, minimising environmental impact, expanding farm land, adapting to crop market developments, adapting to changes in direct payment rates or regulations, seeking professional agronomic, seeking casual advice from friends or colleagues and seeking peer approval.

Ethical approval and pre-registration

The survey campaign and research design were both approved separately by the ETH Zürich Ethics Commission as proposal 2023-N-212 as well as the FiBL Ethics Committee as proposal FSS-2023-006. Copies of the approval letters are included in the supplementary material1. Before launching our survey, we also submitted two research plans for pre-registration of hypotheses via the online platform AsPredicted operated by the University of Pennsylvania (link: AsPredicted). For further information on these, see AsPredicted #153145 and AsPredicted #153146 that were registered on 29th November 2023.

Survey implementation

The survey was implemented as an online survey formulated with Lime Survey and distributed via email. All eligible farms received an individualised email addressed personally to the recipient and a survey link, connected with a unique token to enable us to link the farmer responses with secondary data available for each farm. The participants were asked to give their permission for this by approving the terms and conditions we made available to them regarding how their data would be handled. By agreeing to the disclosure agreement, the farmers gave their permission for the anonymised data, that they subsequently provide through the survey, to be used exclusively for science and research purposes. Farmers were also given the option to opt out of the survey at any time, with no explanation needed. To incentivise participation in the survey we offered the opportunity to enrol in a lottery of 100 supermarket vouchers worth CHF 150 each and the option to receive a personalised results report comparing the farmers’ answers to the answers of other similar farms. The individualised reports were administered via a bespoke app created using R-Shiny (see technical validation section below for further details).

Prior to the full survey launch, a pilot survey was conducted on a random sample of 1% of eligible farms (150 farms) to test the survey’s functionality and to refine any issues. The pilot survey launched on 30th November 2023, and the full survey went live six days later, on 6th December 2023. The survey was closed on 31st January 2024, after a response period of nearly two months.

Data cleaning

To minimise errors already at the point of data entry, the survey was designed to allow only predefined values or plausible numeric ranges for most variables. Wherever this was not technically feasible, such as in open-text fields or free numeric input, we conducted systematic data cleaning after data collection. Data cleaning involved addressing inconsistencies and missing values. In cases where values were deemed implausible or outliers, they were either removed or corrected if sufficient data from other columns was available. This cleaning procedure was applied to variables related to plant protection product treatments, yield, sowing density, labour input, and demographic information. We include the following to illustrate the approach we took as an example (note all processing codes are available in the supplementary material which outline these decisions on a line-by-line basis):

If in the labour units column, an entry was listed as 48, which was inconsistent with the farm area, this value was corrected to 4.8 using a related column for recalculation. Similarly, we proceeded for the variable age: if a data entry was obviously wrong, such as a year of birth recorded as 60 instead of the demanded format YYYY (1960), and the farmer had entered the column of farming experience 40 years, the value was corrected to ‘1960’ based on logical inference. If no reliable correction could be made, the value was marked as ‘NA’ (Not Available).

To ensure anonymity, apart from removing precise geographical information we also grouped continuous variables such as age and farming experience into categories (e.g. age_group and years_experience_group). The data was anonymised, and no specific details were included that could link individual responses to specific farms. No randomisation was applied to the data. With regard to the secondary data, we also took measures to prevent identification by rounding the variables to the nearest integer (the codes for the processing of this data are also available in the supplementary material).

Data Records

The data consists of one main dataset and two supplementary datasets1. Each dataset has columns representing variables (see the codebook for an elaboration of these variables), with each row corresponding to an individual farm. The main survey dataset “Primary_Data” contains 2,728 rows and 141 columns, providing comprehensive information on demographic details (B-H / CD-CP), participation in soil health programmes (I-S), management practice adoption and knowledge (T-CA), structural farm characteristics (CD-CP), training and advice (CQ-CZ), behavioural and attitudinal factors (DA-EK). The supplementary datasets can be linked to the main dataset via a common key variable (“survey_id” - column A in excel), which assigns a unique identifier to each participating farm and is consistently present across all three datasets.

All data and codes are available for download at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15488101.

The supplementary dataset “Wheat_Data” includes the same farms as the main dataset, but with supplementary data for only those that grew milling wheat in the 2022/2023 farming season. Farms present in the first dataset but not in the second did not produce milling wheat during that period. It consists of 2,217 rows and 13 columns and includes data on wheat production (B-H) and plant protection treatments (I-M).

The additional supplementary dataset “Linked_Secondary_Data” includes any spatial and meteorological data that we did not collect via our survey but were able to link to the farm via the farm ID number. This data consists of variables such as rainfall totals (AK-AV), average temperatures (X-AJ), soil textural variables (T-X), production areas (E-S) and any other relevant geographical information (B-D). All sources used for this data are listed in the codebook. As per the primary data listed above, this data is also adjusted to maintain the anonymity of the farmers. It consists of 2,728 rows and 48 columns and is also available within the provided data repository.

Three accompanying PDF files (“Primary_Data_Codebook”, “Wheat_Data_Codebook” and “Linked_Secondary_Data_Codebook”) provide a comprehensive description of all variables, linking them to the relevant survey questions and offering additional explanations where necessary. Additionally, a PDF document of the complete survey questionnaire used to collect the data is included, available in English, German and French. The questionnaire outlines all survey items and response options. The R scripts in the repository include a quality check script to validate data consistency. However, due to anonymity concerns, exact farm locations are not provided. As a result, scripts that replicate visualisations, such as spatial distributions of farms are not included.

A note on linked secondary data

We used the geodienste.ch website to extract secondary data on agricultural land use in Switzerland. The publicly available data sources, which are regularly updated by the responsible authorities for planning and monitoring purposes, provide detailed information on land use by farm. We extracted the relevant datasets for 2022/2023 and include summarised versions of this to complement our primary data collection, presented above. The secondary data from geodienste.ch is helpful for contextualising our results and enables an enriched analysis of agricultural practices in different regions via the inclusion of highly detailed and spatially explicit factors unique to each farm, such as soil texture, geomorphology and weather records. If you wish to use further geographical data - beyond the summarised versions that we include - available via geodienste.ch or any other open data provider in conjunction with the presented data, please follow the individual licensing agreements of these providers.

Technical Validation

Survey design verification

Throughout the execution of the data collection process, we followed a rigorous protocol and sought a wide range of advice from different people and sources over the course of 2023. We did this to ensure the technical validity of our questions and that the scope of our survey was both appropriate and in line with other contemporary surveys undertaken in Switzerland. Summary statistics comparing our survey with responses to the previously conducted surveys are presented below in Table 3.

We iteratively tested the survey with four soil scientists, three agricultural advisors and two farmers during the design of the questions and structure to get their feedback and ensure the highest possible levels of comprehensibility and functionality. Additionally, we tested the different language drafts with six native speakers (three German-speaking and three French-Speaking) to ensure that the contents were understandable, the wording was uniform and the questions identical across language versions.

Survey responses verification

Response rate

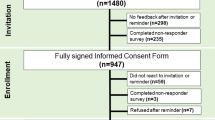

In total, the survey was sent to 15,023 eligible farms, of which 2,728 fully completed the survey, yielding a completion rate of 18.16%. This response rate is comparable with, or higher than, similar agricultural surveys that have been conducted in Switzerland45,46,47,48,49. From the 3,515 farmers that started the survey 779 farmers started but did not finish the survey. Eight responses were excluded due to incomplete or invalid data, specifically, if respondents indicated they were not involved in any farm management decisions. The click-through-to-completion rate for the survey was 77.24%, which is also comparable to other studies in Switzerland (3,515 started vs 2,728 finished).

The farms who responded to our survey span the diverse agricultural landscapes of Switzerland and the two major cultural regions (French and German-speaking Switzerland). To verify the representativeness of the survey responses, we compared the geographical distribution of farms that completed the survey (Fig. 3), those that started but did not complete (Fig. 4), and the overall completion rate (Fig. 5). There is no indication of systematic no-response bias across the regions and higher farm numbers within a cell are often linked to the higher number of farms present within the area. It should be noted that the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland is not included in this study due to its distinct agricultural practices and environmental conditions, which differ significantly from those in the other regions north of the main alpine chain, as well as the limited number of participants who met the survey’s requirements. It should be noted that we can only present the geographic distribution and structural summary statistics of the response trends for the farms that were possible to link to the secondary data. This explains the slight discrepancy between the number of observations in our cleaned datasets and the structural comparisons presented below in Tables 2 and 3.

This figure illustrates the geographical distribution of all farms that both received a survey invitation and fully completed the survey. The majority of farms are concentrated in valley zones, where arable farming is most viable due to favourable environmental conditions. The grey lines outline the cantons, providing a spatial reference for orientation.

This figure displays the percentage of farms that completed the survey out of all contacted farms that were eligible for the survey in each 50 km2 hexagonal grid cell. The values represent relative proportions of completed surveys within each hexagonal cell, rather than absolute counts. Completion rates in cells with very small sample sizes may be statistically less reliable. The grey lines outline the cantons, providing a spatial reference for orientation.

Structural comparisons of respondents

To further assess the representativeness of our sample and understand whether any systematic biases and/or respondent self-selection biases are present, we compare descriptive farm structural statistics of all farms that were contacted during our survey campaign by their overall response state.

Overall, the sample of respondents that completed the survey are very comparable to the entire population, as well as the two cohorts of non-complete respondents. However, there are some noticeable differences, firstly in terms of land usage and farm size (Table 2). For instance, the farms that completed the survey tended to farm slightly larger areas and also had a lower proportion of temporary grassland in the rotation. Temporary grassland share acts as a proxy for the degree of specialisation in livestock production, and higher temporary grassland shares are typically found in the mountain and hill regions. This suggests that farms - of the farms that met the selection criteria - which are relatively more engaged in livestock production are slightly less represented in the survey. Additionally, as can be seen in Fig. 5 and Table 2, farms in the border regions, which are geographically consistent with the areas where arable farming becomes more constrained by geography (e.g. in the mountain and hill zones shown in Fig. 1), also had a lower tendency to respond to the survey.

Comparison with other surveys

Farm and management characteristics

As a further descriptive validation of the dataset collected, we now present a comparison of farm management and farm structural statistics within Table 3. We include the three most recent surveys undertaken at a large scale across Switzerland that focused on wheat production and arable farming - or in the case of Späti et al.48 across multiple cantons48,49,50. We include the variables that were covered in our survey - which took inspiration from the survey campaigns here presented - to indicate the representativeness of our sample and the validity of our dataset. In general, there is very good agreement between the data collected in these three surveys and the data we collected that is presented within this data descriptor.

Milling wheat production

We also include a comparison table (Table 4) to validate the responses relating to milling wheat production, which is available for the subset of farms that produced milling wheat in 2022/2023. This data is named “Wheat_Data” within the data repository. Whilst the official data available from the Swiss national agricultural research institute (Agroscope) comes from a sample size smaller than the sample of respondents in the dataset presented in this descriptor, there is good agreement between sources in terms of average yields51. Additionally, the relative level of crop input usage of our sample of farms are within the recommended - and legally allowed - application levels for each production system.

Feedback and results dissemination

Following the completion of the data collection phase we took further steps to get feedback on the quality of the responses that we received from checking the data with colleagues to sharing the results with the farmers and allowing them to give us feedback. One of the incentives for encouraging farmers to participate in our survey was the offer of receiving a personalised benchmarking report. Within this, the performance of the farm in terms of the number and extent of soil management practices used were directly compared to other similar farms. Such results reports have also been offered in other contemporary surveys in Switzerland46,47.

Because of the very large number of responses, we opted to do this in a digital format via the creation of a bespoke R-Shiny app that we sent to the 2,001 farmers who requested the benchmarking report (the application is free to view at: https://fibl.shinyapps.io/InBestSoil/). Each farmer was issued with a unique 15-character token which enabled them to benchmark the answers they gave in the survey against other farms. The application is interactive in that farmers could filter by many different factors – i.e. farm size, geographic area and production system – so that they could compare the results in whatever way they liked.

By developing the benchmarking application, we sought to give farmers actionable insights derived from their own data, enabling them to assess their practices in relation to similar farms and identify potential areas for improvement. Development of this benchmarking application began in March 2024, after the end of the survey campaign on the 31st of January 2024. The above linked version of the live application was sent via email to the farmers on 11th of June 2024. The farmers were able to provide feedback on the survey and application. While the overall feedback response rate was low, the feedback received was highly positive. The benchmarking platform was accessed for approximately 400 hours between launch on the 11th of June 2024 and mid-August 2024, relating to an average usage of approximately 15 minutes per responder who was given access. Aside from sharing the application with the farmers who participated, we also presented the application to the Swiss Federal Office of Agriculture on 22nd October 2024 and received very positive feedback on the survey, data collected, and the scope of the benchmarking application created.

Usage Notes

The datasets that we provide via Zenodo, and described via this data descriptor, can be used for analysing the adoption dynamics of environmentally beneficial arable soil management practices within Switzerland. This can be insightful for informing policymakers, as well as agricultural extension organisations, with regard to how to better integrate and expand the uptake of these practices by farmers. This dataset also allows a thorough comparison of the differences in adoption rates between three separate production systems. To this end, the datasets can also be used to identify drivers and barriers to adoption (at the extensive and at the intensive margins), understand farmer decision-making behaviour, joint adoption decisions of complementary practices vs. crowding out effects, perceived challenges and attitudes towards given production goals within, and between these three production systems. Beyond ex-post analyses, these behavioural components can also be employed for the parameterisation of farm-level models.

The primary dataset is complemented by detailed milling wheat production data covering a large proportion of the participating farms. These data may be used to analyse productivity and wheat enterprise performance whilst also taking into account highly detailed, and often omitted, geographic and environmental constraints - as supplied via the linked secondary data. To the same end, this data can also be utilised to inform ex-ante modelling efforts.

We recommend that any studies looking to utilise this dataset for an analysis should further screen the data for outliers using a multivariate outlier detection algorithm such as BACON52. In our own subsequent research using this data we follow this same protocol.

Code availability

The code and the survey data are available on Zenodo in the following repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15488101.

References

Rees, C., Ineichen, L., Finger, R. & Grovermann, C. Soil health on Swiss arable farms: data covering soil management practices, farm characteristics and decision drivers. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.15488102 (2025).

Lehmann, J., Bossio, D. A., Kögel-Knabner, I. & Rillig, M. C. The concept and future prospects of soil health. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1, 544–553 (2020).

Borrelli, P. et al. Policy implications of multiple concurrent soil erosion processes in European farmland. Nat Sustain 6, 103–112 (2023).

Adhikari, K. & Hartemink, A. E. Linking soils to ecosystem services — A global review. Geoderma 262, 101–111 (2016).

Lal, R. et al. Soils and sustainable development goals of the United Nations: An International Union of Soil Sciences perspective. Geoderma Regional 25, e00398 (2021).

Jónsson, J. Ö. G. & Davíðsdóttir, B. Classification and valuation of soil ecosystem services. Agricultural Systems 145, 24–38 (2016).

Frank, S. et al. Enhanced agricultural carbon sinks provide benefits for farmers and the climate. Nat Food 5, 742–753 (2024).

Bossio, D. A. et al. The role of soil carbon in natural climate solutions. Nat Sustain 3, 391–398 (2020).

Rawls, W. J., Pachepsky, Y. A., Ritchie, J. C., Sobecki, T. M. & Bloodworth, H. Effect of soil organic carbon on soil water retention. Geoderma 116, 61–76 (2003).

Pascual, U. et al. On the value of soil biodiversity and ecosystem services. Ecosystem Services 15, 11–18 (2015).

Wagg, C., Bender, S. F., Widmer, F. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Soil biodiversity and soil community composition determine ecosystem multifunctionality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 5266–5270 (2014).

Cozim-Melges, F. et al. The effect of alternative agricultural practices on soil biodiversity of bacteria, fungi, nematodes and earthworms: A review. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 379, 109329 (2025).

Panagos, P. et al. Projections of soil loss by water erosion in Europe by 2050. Environmental Science & Policy 124, 380–392 (2021).

Panagos, P. et al. Cost of agricultural productivity loss due to soil erosion in the European Union: From direct cost evaluation approaches to the use of macroeconomic models. Land Degradation & Development 29, 471–484 (2018).

Sartori, M. et al. Remaining Loyal to Our Soil: A Prospective Integrated Assessment of Soil Erosion on Global Food Security. Ecological Economics 219, 108103 (2024).

Montanarella, L. & Panagos, P. The relevance of sustainable soil management within the European Green Deal. Land Use Policy 100 (2020).

Panagos, P., Borrelli, P. & Robinson, D. FAO calls for actions to reduce global soil erosion. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 25, 789–790 (2020).

Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission). EU Missions: Soil Deal for Europe: What Is the EU Mission: A Soil Deal for Europe. (Publications Office of the European Union, 2023).

Wuepper, D. et al. Agri-environmental policies from 1960 to 2022. Nat Food 5, 323–331 (2024).

Williams, H., Colombi, T. & Keller, T. The influence of soil management on soil health: An on-farm study in southern Sweden. Geoderma 360, 114010 (2020).

Teng, J. et al. Conservation agriculture improves soil health and sustains crop yields after long-term warming. Nat Commun 15, 8785 (2024).

Krauss, M. et al. Reduced tillage in organic farming affects soil organic carbon stocks in temperate Europe. Soil and Tillage Research 216, 105262 (2022).

Krauss, M. et al. Impact of reduced tillage on greenhouse gas emissions and soil carbon stocks in an organic grass-clover ley - winter wheat cropping sequence. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 239, 324–333 (2017).

Krauss, M. et al. Enhanced soil quality with reduced tillage and solid manures in organic farming – a synthesis of 15 years. Sci Rep 10, 4403 (2020).

Chiriacò, M. V. et al. A catalogue of land-based adaptation and mitigation solutions to tackle climate change. Sci Data 12, 166 (2025).

El Benni, N., Grovermann, C. & Finger, R. Towards more evidence-based agricultural and food policies. Q Open 3, qoad003 (2023).

Wuepper, D. Does culture affect soil erosion? Empirical evidence from Europe. European Review of Agricultural Economics 1–35 https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/jbz029 (2019).

Wang, Y., Schaub, S., Wuepper, D. & Finger, R. Culture and agricultural biodiversity conservation. Food Policy 120, 102482 (2023).

Federal Office for the Environment, F. Swiss National Soil Strategy for Sustainable Soil Management. https://www.bafu.admin.ch/bafu/en/home/themen/thema-boden/boden--publikationen/publikationen-boden/bodenstrategie-schweiz.html (2020).

Huber, R. Einführung in die Schweizer Agrarpolitik. (vdf Hochschulverlag AG, 2022).

Huber, R., Benni, N. E. & Finger, R. Lessons learned for other European countries from Swiss agricultural policy reforms. Bio-based and Applied Economics (2023).

Federal Office of Agriculture. Direktzahlungen. Direktzahlungen https://www.blw.admin.ch/blw/de/home/instrumente/direktzahlungen.html (2023).

AGRIDEA. Wirz Handbuch Pflanzen und Tiere 2024. (Wirz Verlag, Basel, 2023).

Federal Office of Agriculture, F. Produktionssystembeiträge. Produktionssystembeiträge https://www.blw.admin.ch/blw/de/home/instrumente/direktzahlungen/produktionssystembeitraege23.html (2024).

Federal Office of Agriculture, F. Ökologischer Leistungsnachweis. Ökologischer Leistungsnachweis https://www.blw.admin.ch/blw/de/home/instrumente/direktzahlungen/oekologischer-leistungsnachweis.html (2023).

SFSO. Landwirtschaftsbetriebe, Beschäftigte, Nutzfläche nach Kanton - 2000-2023 | Tabelle. (2024).

Finger, R. & Möhring, N. The emergence of pesticide-free crop production systems in Europe. Nat. Plants 10, 360–366 (2024).

Finger, R. & Möhring, N. Evidence for promoting pesticide-free, non-organic cereal production. Food Policy 137, 102911 (2025).

Möhring, N. & Finger, R. Pesticide-free but not organic: Adoption of a large-scale wheat production standard in Switzerland. Food Policy 106, 102188 (2022).

SFSO. Landwirtschaftliche Nutzfläche ohne Sömmerungsweiden - 1985-2024 | Tabelle (2025).

SFSO. Getreideproduktion, Entwicklung - 1998-2023 | Tabelle (2024).

SFSO. Landwirtschaftsbetriebe nach betriebswirtschaftlicher Ausrichtung - Nach Region - Anzahl Betriebe (in Tausend) - 2023 | Diagramm (2024).

Weersink, A. & Fulton, M. Limits to Profit Maximization as a Guide to Behavior Change. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 42, 67–79 (2020).

Pannell, D. & Zilberman, D. Understanding Adoption of Innovations and Behavior Change to Improve Agricultural Policy. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 42, 3–7 (2020).

Kreft, C. S., Angst, M., Huber, R. & Finger, R. Social network data of Swiss farmers related to agricultural climate change mitigation. Data in Brief 35, 106898 (2021).

Zachmann, L., McCallum, C. & Finger, R. Data on Swiss grapevine growers’ production, pest management and risk management decisions. Data in Brief 51, 109652 (2023).

Zachmann, L., McCallum, C. & Finger, R. Farm-level data on production systems, farmer- and farm characteristics of apple growers in Switzerland. Data in Brief 50, 109531 (2023).

Späti, K., Huber, R., Logar, I. & Finger, R. Data on the stated adoption decisions of Swiss farmers for variable rate nitrogen fertilization technologies. Data in Brief 41, 107979 (2022).

Möhring, N. & Finger, R. Data on the adoption of pesticide-free wheat production in Switzerland. Data in Brief 41, 107867 (2022).

Kreft, C., Akter, S., Finger, R., McCallum, C. & Möhring, N. Data on the adoption of integrated pest management (IPM) practices in wheat production in Switzerland. ETH Zurich https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000702176 (2024).

Schmid, D., Hoop, D., Renner, S. & Jan, P. Betriebszweigergebnisse 2023: Stichprobe Betriebsführung. https://doi.org/10.34776/BETR23-D (2024).

Béguin, C. & Hulliger, B. The BACON-EEM algorithm for multivariate outlier detection in incomplete survey data. Survey Methodology Statistics Canada 34, 91–103 (2008).

Morris, N. L., Miller, P. C. H., Orson, J. H. & Froud-Williams, R. J. The adoption of non-inversion tillage systems in the United Kingdom and the agronomic impact on soil, crops and the environment—A review. Soil and Tillage Research 108, 1–15 (2010).

Hegglin, D., Clerc, M. & Dierauer, H. Reduzierte Bodenbearbeitung. 12, https://www.fibl.org/de/shop/1652-bodenbearbeitung (2014).

Niggli, J., Böhler, D. & Schmid, T. Humuswirtschaft: Humus aufbauen – Bodenfruchtbarkeit erhalten. 20, https://www.fibl.org/de/shop/1314-humuswirtschaft (2024).

Hedrich, T. et al. Zwischenfrüchte im biologischen Acker- und Gemüsebau. 16, https://www.fibl.org/de/shop/1168-zwischenfruechte (2024).

Berner, A. Grundlagen zur Bodenfruchtbarkeit - Die Beziehung zum Boden gestalten. (2013).

Agridea. Deckungsbeiträge 2024. in 52 (Eschikon 28, CH-8315 Lindau, 2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to numerous colleagues for their advice and suggestions throughout the survey design and data collection. In particular we would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance of Haris Papagiannakis for the survey implementation in LimeSurvey; support from Raphaël Charles and Marina Wendling for assisting with the survey design and French translation; support from colleagues at the Ebenrain Centre for Agriculture for assisting with the survey design and German translation; support from Jeremias Niggli and Daniel Böhler for the advice on soil management practices in Switzerland; as well as numerous colleagues who tested and gave constructive feedback on the survey. Thanks to all of them, our work was greatly improved. We would also like to commend the support of the Federal Office of Agriculture who authorised our survey and provided us with the contact information of the farms meeting our selection criterion. Particular thanks go to Diego Gil for his assistance with this. Similarly, we would also like to acknowledge the funding for this analysis which came from the InBestSoil project (HORIZONMISS-2021-SOIL-02: Project ID: 101091099), without which our work would not have been possible. Last but by no means least, we would like to thank the massive contribution in time and effort from all the farmers who filled out our survey. We were truly inspired by their engagement and passion for the topic. We hope that they were also able to get some useful information back from us via the benchmarking application. We used AI assisted copy editing for this paper.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Charles Rees: Conceptualisation, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration. Lorin Ineichen: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualisation. Robert Finger: Conceptualisation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. Christian Grovermann: Conceptualisation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rees, C., Ineichen, L., Finger, R. et al. Data covering soil management practices and farm characteristics on Swiss arable farms. Sci Data 12, 1471 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05731-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05731-0