Abstract

The Human Development Index (HDI) is widely recognized as a key measure for assessing progress in health, education, and income. China’s remarkable advances in human development, coupled with pronounced internal disparities, present a unique context for examining regional development trajectories. Existing HDI datasets, however, often focus on national or provincial scales, leaving finer details at the prefecture level underexplored. Here we introduce the Chinese Human Development Index (CHDI) dataset for the period 2010–2020, which extends the HDI framework to a more granular spatial scale. It encompasses the CHDI values, the three underlying dimension indices (health, education, and income), and the four indicators required to construct them: life expectancy at birth, mean years of schooling, expected years of schooling, and gross national income per capita. These indicators were compiled from population censuses, official development plans, and other authoritative statistical sources. The dataset’s fine-grained resolution and methodological rigor ensure both temporal and spatial comparability, providing a robust empirical foundation for analyzing evolving patterns, policy mechanisms, and regional divergences in China’s human development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The Human Development Index (HDI), since its introduction by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 1990, has served as a key benchmark for assessing a country’s overall progress in health, education, and income. Over the past three decades, the UNDP has periodically updated the HDI of most economies, providing indispensable insights that complement traditional economic indicators. China’s trajectory in HDI is particularly noteworthy: it is the first country to progress from low (HDI ≤ 0.550) to high (HDI > 0.700) human development since 19901. While China’s success in advancing human development underpins global human development, the subnational regional disparities within the country remain an area of academic and policy interest2,3,4,5. Understanding these subnational disparities not only sheds light on how developing countries or regions might close the gap with more developed counterparts, but also informs development strategies and policies for achieving both economic prosperity and social well-being—a goal that demands more precise and robust data.

Existing HDI datasets, however, are typically aggregated at the national level, potentially obscuring inequalities at smaller regional scales. Recognizing this limitation, Smits & Permanyer6 compiled subnational HDI for 161 countries from 1990 to 2017—recently updated to 20227—that includes China’s province-level HDI. In addition, the UNDP’s China National Human Development Reports have periodically released province-level HDIs dating back to 1990. Some editions, such as the 2019 report1 (to which our team also contributed), provide limited data at the prefecture level for selected years. Despite these advances, current datasets still do not fulfill the research needs.

Several issues persist. First, given China’s large population and geographic diversity, estimating province-level HDI alone cannot capture the fine-grained spatial heterogeneities and local development dynamics2,5. Second, methodological inconsistencies in calculating China’s subnational HDI across different UNDP reports render cross-temporal comparisons problematic1,6,8. Third, reliance on outdated data sources—often coupled with extrapolation of health and education indicators—might lead to misjudgment of subnational development based on erroneous linear trends9. This has prompted scholars to shift toward using more diverse, timely, and spatially granular indicators10,11, as well as adopting more advanced and spatially sensitive estimation techniques12,13,14, to more accurately capture the dynamics of subnational human development.

To address these shortcomings, this study presents a newly constructed dataset of HDI at both the province and prefecture levels in China from 2010 to 2020, which is built on the latest population census data released by the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC) and the most recent official development plans documents issued by Chinese province- and prefecture-level governments. By integrating the internationally recognized HDI framework with the latest socio-economic data from China, this newly developed dataset provides the first longitudinal HDI calculation at the prefecture level, enabling more accurate analysis of human development patterns across the country. It supports three key applications. First, it offers a temporal lens to investigate the evolution of China’s subnational human development over the past decades. Second, it facilitates spatial analysis of regional heterogeneities in human development across China’s administrative hierarchy. Third, by integrating causal inference methodologies, it can help identify the policy effects and institutional mechanisms that have shaped China’s human development outcomes. In doing so, this new dataset provides a richer empirical foundation for understanding human development within China and globally.

Methods

China’s sub-national administrative divisions are organized into three levels: province, prefecture, and county level. Among them, the prefecture level serves as a fundamental layer in connecting the whole administrative system and coordinating regional economic and social development15. We extend the UNDP’s national HDI (https://hdr.undp.org/data-center) to subnational scales in China, constructing the Chinese Human Development Index (CHDI) at both the province and prefecture levels. Following the UNDP’s methodology16, the CHDI is defined as the geometric mean of three dimension indices—health, education, and income index. The health index is calculated using life expectancy at birth (LEXP); the education index is derived from mean years of schooling of the population aged 25 and older (MYS25), coupled with expected years of schooling (EYS); and the income index is based on gross national income per capita (GNI per capita). Table 1 provides overview of indicator definitions, thresholds, and data sources.

The CHDI dataset covers 31 province-level and 331 prefecture-level administrative divisions in mainland China from 2010 to 2020. The scope of this sample covers the vast majority of subnational regions in China. Only two prefecture-level administrative divisions (i.e., Danzhou City and Sansha City) are not included due to data availability.

Data scope

To ensure uniformity and comparability, the administrative divisions at both the province and prefecture levels are standardized using the 2020 classification. According to the Ministry of Civil Affairs of China (http://xzqh.mca.gov.cn/map), mainland China comprises 31 province-level and 333 prefecture-level administrative divisions as of 2020. The CHDI dataset includes 31 provinces and 331 prefectures, covering nearly all subnational units. Two prefectures—Danzhou and Sansha—are excluded due to data availability constraints.

Data sources

We use three main data sources to construct the CHDI dataset: (1) population censuses, (2) official development plans, (3) authoritative publications, and other open databases.

Population censuses

China conducts a nationwide population census every decade, complemented by a 1% population sampling survey conducted midway between consecutive censuses. These data collections cover key demographic and socioeconomic variables such as gender, age, ethnicity, educational attainment, occupation, migration, social security, marriage, fertility, mortality, and housing conditions. For this study, we collect national statistical yearbooks of 2010 census (https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm) and 2020 census (https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/7rp/indexch.htm), along with provincial statistical yearbooks of 2010 census, 2015 1% population sampling survey, and 2020 census (https://data.cnki.net/). These yearbooks provide essential data on population size, mortality, and educational attainment necessary for estimating LEXP and MYS25.

Development plans

Development planning (also known as five-year plans) in China serve as a critical tool for managing public affairs and guiding socioeconomic progress17. The two main types of development plans used here are comprehensive plans (zongti guihua) and special plans (zhuanxiang guihua). The former are comprehensive frameworks encompassing economic, social, technological, ecological, and cultural domains, while the latter target specific facets of development. Given the hierarchical nature of these documents (comprehensive plans have a higher order than special plans), we prioritize data from the former and supplement as needed with the latter.

Both comprehensive plans and special plans typically include specified targets and corresponding baseline values at the start of each planning period. For example, the 14th Five-Year Plan specifies the main targets for 2021–2025, along with their baseline values as of 2020. Similarly, it retrospectively reviews the achievements of the 13th Five-Year Plan period (2016–2020), including actual values recorded at the start and the end of that period. Given that these plans are drafted by government agencies at the province- and prefecture-levels and approved by corresponding legislative bodies (i.e., province- and prefecture-level people’s congresses), their data are authoritative and rigorous. However, these plan documents, which often include important data not integrated into the officially released statistical pipelines, have been largely overlooked and underutilized in existing HDI calculations for China. We leverage these sources to improve accuracy and granularity of HDI estimates. For instance, these documents often report LEXP (particularly for non-census years) and gross enrollment rates (GERs)—indicators that are not readily or systematically available in other official databases or publications.

For this study, we manually collect relevant comprehensive plans and special plans in health and education dimensions from province- and prefecture-level government websites and through formal information disclosure requests. These sources supplement and validate census-derived estimates of LEXP and crucial data on GER for calculating EYS.

Open databases and other official publications

To estimate LEXP and GER not captured by population censuses or development plans, we draw on additional sources. These include the NBSC database (https://data.stats.gov.cn), statistical yearbooks and bulletins (https://data.cnki.net/), as well as government work reports, and policy documents from province- and prefecture-level government websites. We also obtain some LEXP data by submitting information disclosure requests to provincial bureaus of statistics. Meanwhile, to estimate GNI per capita, we obtain province-level gross domestic product per capita (GDP per capita) data from the NBSC database and prefecture-level GDP per capita data from the CEIC database (https://www.ceicdata.com.cn/en).

Estimating the CHDI components

Health dimension

In China, the estimation of LEXP is complicated by the distribution of population and mortality data across multiple government agencies—including the National Health Commission, the Ministry of Public Security, and the NBSC—and the limited public availability of these data. This institutional fragmentation often leads to discrepancies in regional LEXP estimates and a scarcity of systematic assessments, particularly at the prefecture level.

Step 1: Estimating province-level LEXP. We obtain province-level LEXP for 2010 and 2020 from census data released by the NBSC. We further retrieve province-level LEXP for 2015 from a range of official sources, including comprehensive plans, health-related special plans, and other authoritative publications.

Step 2: Estimating prefecture-level LEXP for 2010. Prefecture-level LEXP for 2010 are estimated by submitting information disclosure requests to provincial bureaus of statistics and using abridged life tables. This is because most prefecture-level governments had not yet designated LEXP as a main target during the 12th Five-Year Plan period (2011–2015), making prefecture-level LEXP for 2010 unavailable through development plans. Adhering to the principle of prioritizing official data, we submit information disclosure requests to the statistics bureaus of 27 provinces. Ultimately, 5 provinces provide us with the 2010 LEXP values for their prefecture-level administrative divisions. For the remaining 22 provinces, we employ abridged life tables to estimate the 2010 LEXP values for their prefecture-level administrative divisions. The life table method is widely employed for LEXP estimation in HDI calculations18. We draw age-specific population data from the Tabulation on the 2010 Population Census of the Peoples Republic of China by County19 and age-specific mortality data from provincial census yearbooks. The following equations detail the procedures for computing LEXP using an abridged life table.

First, we calculate the mortality rate and probability of dying for each age group. Let \({}_{n}m_{x}\) denote the crude mortality rate for the age group x to x + n, defined as the number of the reported deaths \(({}_{n}d_{x})\) divided by the mean population \(({}_{n}P_{x})\) in that age group. To correct for underreporting of deaths (URD), we introduce the parameter β, representing the proportion of underreported deaths. The adjusted mortality rate \(({}_{n}m_{x}^{{\prime} })\) is then:

The probability of dying \(({}_{n}q_{x})\) for the age group x to x + n is obtained by converting the adjusted mortality rate as follows:

Here, \({m}_{0}{\prime} \) is the adjusted infant mortality rate, and ω represents the highest age group. For simplicity, it is assumed that the underreporting rate of deaths is consistent across all age groups above 5 years. For the highest age group, the probability of dying is set to 1.

Underreporting of deaths in China’s population censuses, especially among the younger age groups, is well documented20,21. We therefore pay particular attention to the estimation of \({m}_{0}^{{\prime} }\), the probability of dying among children aged 1–4 (\({}_{4}q_{1}\)), and the underreporting rate of deaths for age groups above 5 years (β). For each prefecture-level administrative division, we apply the province-level adjusted values of \({m}_{0}^{{\prime} }\) and \({}_{4}q_{1}\) estimated by Huang & Zeng22. Using these adjustments, along with the province-level LEXP for 2010 released by the NBSC, we estimate the β for each province and apply the same β-value to its respective prefecture-level administrative divisions. Table 2 provides the values of these parameters. The reliability of these parameter settings is further discussed in the technical validation section.

Second, we use the adjusted mortality parameters to construct abridged life tables, calculating the number of deaths \(({}_{n}d_{x})\), survivors (lx), person-years lived \(({}_{n}l_{x})\), and cumulative person-years lived (Tx).

The person-years lived for each age interval is:

Here, l0 is initiated at l0 = 100,000. a0 refers to the fraction of a year lived by an infant. Following Chiang’s recommenndations23, when the infant mortality rate is below 20‰, we set a0 = 0.09; when the infant mortality rate falls between 20‰ and 40‰, we set a0 = 0.15. The results are consistent across these thresholds.

Finally, we calculate LEXP.

ex refers to the expected number of years remaining for an individual at age x. When x = 0, e0 represents to LEXP. Of the 331 prefecture-level divisions included in the CHDI dataset, 71 use official reported data, 255 use the abridged life table-based estimate; 5 values are extrapolated forward using data from subsequent years, due to missing official values and excessive errors in life table-based estimates.

Step 3: Estimating prefecture-level LEXP after 2010. As of July 2024, we acquired 14th Five-Year Plans for 327 prefecture-level administrative divisions (98.8% coverage), most of which report LEXP in 2020, and some in 2015. For those not reporting LEXP in their comprehensive plans, we use health-related special plans or other official publications to fill gaps. Notably, while LEXP reporting at the prefecture level was limited prior to 2015, it became more common thereafter, yielding 809 observations from 2015 to 2020. Because no systematic adjustments for underreporting deaths are currently available for the 2020 census, using abridged life tables to estimate LEXP in 2020 may lead to inaccuracies. Hence, we rely directly on LEXP values reported in development plans and other official publications for that year.

Education dimension

Indicators for the education dimension include MYS25 and EYS.

Step 1: Estimating MYS25. MYS can be converted from the duration of each level of education by using a population-weighted measure24:

Here, MYSn refers to the mean years of schooling of the population aged n and above, and Pnk refers to the proportion of the population in this age group that has completed k years of schooling. We follow the conversion standard provided by the NBSC: primary school=6 years, junior secondary school=9 years, senior secondary school=12 years, and junior college and above=16 years25. This conversion standard is largely consistent with internationally accepted one26. Although multiple definitions exist (e.g., MYS for population aged 6 + , 15 + , 25 + , and of the working-age population of 16–59), the UNDP typically uses MYS25 for HDI calculations. Therefore, we estimate MYS25 at both the province and prefecture levels.

Step 2: Estimating EYS. Ideally, EYS is the sum of the age-specific enrollment rates beyond the school age. In practice, given data constraints, an alternative widely accepted method is used, and EYS can be derived from enrollment rates at various educational levels27:

Here, λi refers to the enrollment rate and ai refers to the number of years for each level. We consider four levels: primary education (a1 = 6), junior secondary education (a2 = 3), senior secondary education (a3 = 3), and higher education (a4 = 4). Following the methodology recommended by the UNESCO et al.28, we use GER given its widely adoption in China’s statistical system.

With nine-year compulsory education fully implemented across China29,30, the GERs in primary and junior secondary education exceeded 100%. Therefore, we set the GERs for primary and junior secondary education at the province and prefecture levels uniformly at 100%. Our focus thus shifts to estimating the GERs for senior secondary and higher education. The calculation for EYS reduces to:

We prioritize using the GER data released in the comprehensive plans. For administrative divisions lacking these data, we rely on education-related special plans or other official publications. In some cases, provinces publish information on both the number of enrolled students and the eligible population, allowing for approximation of GERs. GER for higher education at the prefecture level is substituted by the corresponding province-level GER value for two main reasons. First, China’s college entrance examinations (Gaokao) are administered at the provincial level, and the Ministry of Education allocates higher education admissions quotas by province, based primarily on factors such as the provincial population size, the number of candidates, and the capacity of local higher education institutions. As a result, interprovincial differences in GER are systematic and institutionally persistent, whereas intraprovincial variation—mainly stemming from the local distribution of educational resources and other non-institutional factors—tends to be relatively random. Therefore, province-level GER serves as a reasonable and statistically defensible proxy for prefecture-level values. Second, according to the Statistical Indicator System for Monitoring and Evaluating Chinese Education (2025) issued by the Ministry of Education (http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_hygq/hygq_zczx/moe_1346/moe_1348/201909/t20190929_401597.html), official GER statistics for higher education are published only at the national and provincial levels; no disaggregated GER data are available for prefectures. In light of the province-based organization of higher education access and the absence of finer-grained data, this substitution approach is consistent with established data practices and widely accepted methodological standards.

Income dimension

For international comparability, the UNDP employs GNI per capita at constant price (measured at purchasing power parity, PPP) in calculating the HDI. Following the methodology of the UNDP16, we convert province- and prefecture-level GDP per capita into GNI per capita (constant 2017 international $, PPP). The conversion factors are the ratios between China’s GDP per capita (released by the NBSC database) and GNI per capita (released by the CEIC database), for the years 2010–2020.

Addressing missing values

To enable cross-regional comparisons and longitudinal analyses of HDI at the province and prefecture levels for the period 2010–2020, we address missing values as follows.

LEXP: (1) At the province level, missing values are addressed using linear interpolation. (2) At the prefecture level, if there are two or more observed values exist within the target timeframe, linear interpolation is applied to fill in gaps between known values. For extrapolations, we estimate missing values based on the annual rate of change in LEXP observed at the province level. Table 3 presents the data sources for LEXP at both levels.

MYS25: (1)We first obtain MYS15 in 2010 at the province and prefecture levels directly from Tabulation on the 2010 Population Census of the Peoples Republic of China by County19. Using province-level educational attainment data from 2010 census, we calculate province-level MYS25 with the aforementioned conversion standard. We then convert prefecture-level MYS15 into MYS25 by applying the province-level ratio of MYS15 to MYS25. (2) Using data from the 1% population sampling survey in 21 provinces in 2015, MYS25 in 2015 at the province level can be calculated. (3) Since the 2020 census reported both province- and prefecture-level data on educational attainment by level of education, MYS25 at both levels can be calculated directly.

Based on the aforementioned method, we obtain complete data for MYS25 at the province and prefecture levels in 2010 and 2020, along with partial data for MYS25 at the province level in 2015. Missing values are filled using linear interpolation.

EYS: (1) At the province level, we apply linear interpolation and extrapolation to handle missing values of the GERs for senior secondary and higher education. (2) At the prefecture level, the primary focus is on estimating the GER for senior secondary education, as the GER for higher education in each prefecture-level administrative division is assumed to be uniform within each province. If two or more observed values are available within the timeframe, linear interpolation is used to fill intermediate gaps. For extrapolation, we rely on the annual rate of change in GER for senior secondary education at the province level. In cases where no data on senior secondary GER is available for a given prefecture, the corresponding province-level value is used. Table 4 presents the data sources for GER at the province level. Table 5 presents the data sources for GER at the prefecture level.

For LEXP, MYS25, and GERs used to calculate EYS, we employ linear interpolation and extrapolation for two main reasons. First, these indicators exhibit stable, long-term trends suitable for linear estimation. Second, the UNDP adopts this method in its HDI calculations. Additionally, to improve extrapolation accuracy, we align prefecture-level trends with provincial annual changes, similar to the approach of Kummu et al.8, ensuring that the changes in indicators at the prefecture level resemble the temporal patterns of their corresponding higher-level administrative units.

GNI per capita

GNI per capita is obtained by converted from GDP per capita. At the province level, there are no missing values for GDP per capita from 2010 to 2020. At the prefecture level, the missing values for GDP per capita from 2010 to 2020 account for less than 3% of the sample. To address these gaps, we retrieve the GDP and permanent resident population data for the respective prefectures to calculate the missing GDP per capita values.

Calculating dimension indices and CHDI

Following the methodology of the UNDP16, we normalize each indicators (LEXP, MYS25, EYS, and GNI per capita) into 3 dimension indices (health index, education index and income index) on a 0–1 scale using:

For the education dimension, the normalized indices for MYS25 and EYS are first calculated separately. Then, the education index is computed as the arithmetic mean of the two:

Thresholds for each dimension are listed in Table 1. The CHDI is then computed as the geometric mean of the three dimension indices:

Data Records

The CHDI dataset is available on Zenodo31. It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. It contains a total of 31,856 data records, including 2,728 records at the province level and 29,128 records at the prefecture level. Among these records:

-

341 records are for province-level HDI (31 provinces, 2010–2020);

-

341 records are for province-level health index (31 provinces, 2010–2020);

-

341 records are for province-level education index (31 provinces, 2010–2020);

-

341 records are for province-level income index (31 provinces, 2010–2020);

-

341 records are for province-level LEXP (31 provinces, 2010–2020);

-

341 records are for province-level MYS25 (31 provinces, 2010–2020);

-

341 records are for province-level EYS (31 provinces, 2010–2020);

-

341 records are for province-level GNI per capita (31 provinces, 2010–2020);

-

3641 records are for prefecture-level HDI (331 prefectures, 2010–2020);

-

3641 records are for prefecture-level health index (331 prefectures, 2010–2020);

-

3641 records are for prefecture-level education index (331 prefectures, 2010–2020);

-

3641 records are for prefecture-level income index (331 prefectures, 2010–2020);

-

3641 records are for prefecture-level LEXP (331 prefectures, 2010–2020);

-

3641 records are for prefecture-level MYS25 (331 prefectures, 2010–2020);

-

3641 records are for prefecture-level EYS (331 prefectures, 2010–2020);

-

3641 records are for prefecture-level GNI per capita (331 prefectures, 2010–2020).

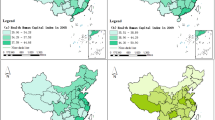

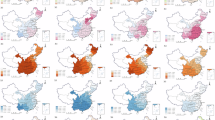

To illustrate spatial and temporal patterns, Figs. 1, 2 present the CHDI for 2010, 2015, and 2020 at the province and prefecture scales, respectively. These maps reveal a general improvement in China’s HDI across subnational regions. While all provinces had reached at least the medium level of human development (≥0.550) by 2010, certain prefectures remained at low levels (<0.550) until 2015, underscoring more pronounced disparities at finer geographic scales.

From a spatial perspective, the progress in HDI has gradually diffused from eastern regions toward central and western parts of the country. Prefecture-level administrative divisions in the eastern region were the first to achieve high human development levels (0.700–0.799) and subsequently advanced toward very high human development levels (>0.8), followed by leading prefecture-level administrative divisions in the central and western regions. By 2020, very high human development prefectures encompassed a population of 442 million, and high human development regions covered 912 million people. Only 21 prefecture-level administrative divisions involving 40.43 million people, remained at medium level. Most prefectures in the core Yangtze River Delta region, large coastal prefectures, and some provincial capitals in the central and western regions have attained very high human development. Prefectures lingering at the medium level are primarily located in the northwest and southwest regions.

With detailed provincial and prefectural division codes, the dataset can be merged with other data sources for comprehensive analyses, supporting applications in regional development studies, policy impact assessments, and comparative research on human development across different countries.

Technical Validation

Comparison with existing datasets

We compare the CHDI dataset with existing databases in three ways. First, we aggregate the province- and prefecture-level CHDI data to the national level (using population weighting) and compare the results with the UNDP’s national HDI estimates for China. As shown in Fig. 3, when scaled up to the national level, the CHDI are closely to the overall trends reported by the UNDP. The values are generally close across dimensions, although the UNDP’s education index is notably lower than that of the CHDI, an issue we discuss in detail below.

Second, we compare our province-level CHDI values (and the prefecture-level values aggregated to the province-level) with other available province-level HDI estimates for China. These include data from China National Human Development Reports published by the UNDP (covering 2010, 2014, and 2017)1,32,33 and the global subnational HDI database7 constructed by Smits & Permanyer6 (covering 1990 to 2022). Figure 4 illustrates that the trends and values in these various databases are largely consistent.

Furthermore, we examine correlations in province-level HDI rankings derived from aforementioned databases. As shown in Table 6, the rankings exhibit high correlation coefficients, demonstrating the reliability of our CHDI database.

Discussion on the health index estimation

To estimate LEXP at the prefecture level for 2010, we need to estimate the URD in the 2010 census. According to Cui et al.34, the national average URD in the 2010 census was about 18.4%. Applying this national average uniformly to all province-level life tables, however, may overlook the heterogeneity in data quality across provinces. To address this, we estimate the URD values for each province by comparing the official 2010 LEXP data from the NBSC database with the life table-based estimates incorporating adjusted infant mortality and probability of dying among children aged 1–4.

Validating this approach across all prefectures is challenging, as most do not release official LEXP for 2010. Nonetheless, we obtain official LEXP values for prefecture-level cities in 5 provinces through formal information disclosure requests procedures, enabling a focused comparison. Figure 5 presents boxplots of LEXP estimates for the 5 provinces, comparing official LEXP values with life table-based estimates. The life table-based estimates are derived using three approaches: (1) the national average URD from Cui et al.34, (2) the province-specific adjusted URD in this study, and (3) no URD adjustments. It can be observed that life table-based estimates without URD adjustments significantly deviate from official LEXP values. Furthermore, we calculate the differences between these life table-based estimates with URD adjustments and official LEXP values. For 71 prefecture-level cities in 5 provinces, the average relative error for LEXP using the national average URD is 1.40%, while the average relative error for LEXP using the province-adjusted URD is 1.12%. This indicates that our province-specific adjustment yields estimates closer to the official statistics.

Discussion on the education index estimation

We find that both the UNDP and Smits & Permanyer may underestimate China’s education index. At the national level, the UNDP’s MYS25 data are drawn from the Barro & Lee database35,36, which has several limitations: (1) its most recent version (v2.2) only extends to 2010, and the UNDP’s approach to subsequent years is unclear; (2) while Barro & Lee report China’s MYS25 as 7.53 in 201036, the UNDP has cited different values (e.g. 7.5 years in the 2010 Human Development Report37 and 6.7 years in the 2024 edition38); and (3) the Barro & Lee database35,36 relied on early cohort data from 1980, 1990, and 2000 to extrapolate recent trends, potentially underestimating the China’s educational progress in recent years.

As shown in Fig. 6, we use China’s census data to calculate the national-level MYS25 and compare it with the MYS25 published by the UNDP and the Barro & Lee database. The UNDP has published China’s MYS25 for all years after 1990, while the Barro & Lee database has published China’s MYS25 for the years 2000, 2005, and 2010. Meanwhile, based on China’s census data, we can calculate MYS25 for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020. Through linear interpolation and extrapolation, we obtain complete MYS25 data for China at the national level from 2000 to 2020 from the above three data sources. It can be seen that the MYS25 calculated based on China’s census data is significantly higher than that from the other two data sources. For example, in 2020, the MYS25 calculated from China’s census data is 9.52 years, which is higher than the 8.11 years published by the UNDP in its 2024 Human Development Report38 and the 7.91 years obtained by extrapolation from the Barro & Lee database.

Comparison of Mean Years of Schooling of the Population Aged 25 and Older at the Nation Level for China. Note: The UNDP38 has published China’s MYS25 for all years after 1990. The Barro & Lee database36 has published China’s MYS25 for the years 2000, 2005, and 2010. Based on China’s census data, MYS25 for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 can be calculated. For the missing data in the latter two data sources, we use linear interpolation and extrapolation.

At the subnational level, Smits & Permanyer’s estimation of China’s province-level education index7,8 also warrant further discussion. First, they adjust the subnational data so that the population-weighted MYS25 aligns with the UNDP’s national estimate6. However, as noted earlier, the UNDP may underestimate China’s national MYS25, rendering Smits & Permanyer’s subnational estimates6,7 vulnerable to a similar bias. As shown in Fig. 7, the province-level MYS25 estimated by Smits & Permanyer is indeed lower than the province-level MYS25 estimated in this study (including both those calculated directly from provincial data and those aggregated from prefectural-level MYS25 through population weighting).

Comparison of Mean Years of Schooling of the Population Aged 25 and Older at the Province Level for China. Note: The province-level MYS25 obtained by aggregating the prefecture-level MYS25 through population weighting is basically consistent with the province-level MYS25 calculated directly in this study. Only Hainan Province is an exception. This is mainly because at the prefecture level, we lack data for Sansha City and Danzhou City, which are two administrative divisions belonging to Hainan Province.

Second, in the absence of direct provincial estimates for EYS, Smits & Permanyer6 approximate it by scaling national-level EYS using ratio of provincial-to-national MYS25, an assumption that may oversimplify the relationship between EYS and MYS25. According to the UNDP’s technical notes16, some regions may have low MYS25 but high EYS. As shown in Fig. 8, we compare the province-level EYS estimated by Smits & Permanyer with the province-level EYS estimated in this study (including both those calculated directly from provincial data and those aggregated from prefecture-level EYS through population weighting). We also include the province-level MYS25 estimated in this study as a reference. The province-level EYS estimated by Smits & Permanyer shows a trend that is generally consistent with the province-level MYS25. However, based on the province-level EYS estimated in this study, it can be observed that the relationship between MYS25 and EYS varies across provinces, with some cases indeed showing low MYS25 but high EYS. Such heterogeneity cannot be captured using Smits & Permanyer’s estimation method.

In comparison, the CHDI dataset draws on more authoritative, recent, and granular data sources. We calculate MYS based on the recent census data (in 2020) and obtain GER data from the latest development plans, both of which are vetted by government statistical agencies and legislative bodies. By leveraging provincial census yearbooks that include prefecture-level data and collecting prefecture-level development plans, we attain finer spatial resolution than estimates relying solely on national- or province-level data.

Limitations and future work

Despite our efforts to compile the most up-to-date province- and prefecture-level HDI in China for 2010–2020, some limitations remain. First, due to the lack of a systematic estimation of URD in the 2020 census across different regions, we rely on official publications rather than life table methods for LEXP in that year. Further research into URD in the 2020 census may enable more accurate life table-based estimates. Second, for prefecture-level EYS, we currently assume uniform higher education GER within each province. This pragmatic approach reflects limited data availability but may overlook local variations in college admission opportunities. Future work could refine these estimates as more localized GER data become available. Third, some of the indicators for certain years are interpolated or extrapolated due to missing values. As more recent and detailed data become available, these estimates can be replaced with more accurate values.

Future research can continue to expand this dataset. First, future research can further extend the time range of this dataset. Due to data availability considerations, we have limited the time range of the dataset in this study to 2010–2020. Our goal is to provide an algorithm for CHDI and validate its feasibility within a period where data are relatively complete. In the future, with the release of new census data and development plans, this dataset can be extended to more recent years, enabling the observation of China’s human development process over a longer time span. Second, future research can further adjust the algorithm or incorporate additional indicators based on this dataset to enrich the connotation and application value of HDI. In this study, we adopt the UNDP framework to ensure comparability with international and other subnational HDI studies and to accurately position China within the global human development process. Future research may follow the UNDP’s approach16 to compute the inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) and the Gender Development Index (GDI). Future research can also incorporate ecological factors and indicators related to sustainable development goals, as attempted in recent studies5,10,11,39, or delve deeper into regional differences, indicator weights and indicator structures within the Chinese context13,14. The structure and granularity of our dataset provide a strong empirical basis for such extensions. Third, future research can also extend this dataset to the county level to further enhance our understanding of subnational human development in China.

Code availability

All data were processed by using Microsoft Office Excel and the generated datasets have been stored as xlsx files and shared on Zenodo31. All maps of this study were generated by Stata.

References

UNDP. National Human Development Report 2019: China https://hdr.undp.org/content/national-human-development-report-2019-china (2019).

Yang, Y. & Hu, A. Investigating regional disparities of China’s human development with cluster analysis: A historical perspective. Social Indicators Research 86, 417–432, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9177-4 (2008).

Xu, Z. et al. Assessing progress towards sustainable development over space and time. Nature 577, 74–78, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1846-3 (2020).

Jiang, M. et al. Different material footprint trends between China and the world in 2007-2012 explained by construction- and manufacturing-associated investment. One Earth 5, 109–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.12.011 (2022).

Jiang, M. et al. Additional north-south differences in China revealed by the planetary pressure-adjusted human development index. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 198, 107191, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.107191 (2023).

Smits, J. & Permanyer, I. The subnational human development database. Scientific data 6, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2019.38 (2019).

Global Data Lab. Subnational HDI Database https://globaldatalab.org/shdi/ (2024).

Kummu, M., Taka, M. & Guillaume, J. H. Gridded global datasets for gross domestic product and Human Development Index over 1990–2015. Scientific data 5, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.4 (2018).

Scherbov, S. & Gietel-Basten, S. Measuring inequalities of development at the sub-national level: From the human development index to the human life indicator. PLoS One 15, e0232014, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232014 (2020).

Hickel, J. The sustainable development index: Measuring the ecological efficiency of human development in the anthropocene. Ecological Economics 167, 106331, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.05.011 (2020).

Dong, Y., Jin, G., Deng, X. & Wu, F. Multidimensional measurement of poverty and its spatio-temporal dynamics in China from the perspective of development geography. Journal of Geographical Sciences 31, 130–148, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-021-1836-x (2021).

Jin, G. et al. Trade-offs in land-use competition and sustainable land development in the north China plain. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 141, 36–46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.01.004 (2019).

Luo, X., Qin, J., Wan, Q. & Jin, G. Spatial human development index in China: Measurement and interpretation based on Bayesian estimation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, 818, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010818 (2023).

Mareeh, H., Li, P., Sun, Y., Zhang, R. & Li, A. Advancing human development assessment in Chinese cities: A novel data envelopment analysis-based benefit of the doubt approach. Social Indicators Research https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-025-03601-1 (2025).

Ma, L. J. C. Urban administrative restructuring, changing scale relations and local economic development in China. Political Geography 24, 477–497, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2004.10.005 (2005).

UNDP. Human Development Report 2023/2024 Technical Notes https://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2023-24_HDR/hdr2023-24_technical_notes.pdf (2024).

Heilmann, S. & Melton, O. The reinvention of development planning in China, 1993–2012. Modern China 39, 580–628, https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700413497551 (2013).

Preston, S. H., Heuveline, P. & Guillot, M. Demography: Measuring and modeling population processes. (Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2001).

Population Census Office under the State Council & Department of Population and Employment Statistics in National Bureau of Statistics of China. Tabulation on the 2010 population census of the Peoples Republic of China by county. (China Statistical Press, 2012).

Yang, G. et al. Mortality registration and surveillance in China: History, current situation and challenges. Population Health Metrics 3, 3, https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-3-3 (2005).

Cai, Y. China’s new demographic reality: Learning from the 2010 census. Popul Dev Rev 39, 371–396, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00608.x (2013).

Huang, R. & Zeng, X. Infant mortality reported in the 2010 census: Bias and adjustment (in Chinese: “六普”报告的婴儿死亡率误差和实际水平的估计). Population Research 37, 3–16 (2013).

Chiang C. L. Life table and its applications. (Krieger Pub Co, 1983).

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. UIS Methodology for Estimation of Mean Years of Schooling https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/uis-methodology-for-estimation-of-mean-years-of-schooling-2013-en_0.pdf (2013).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census (No.6) https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202105/t20210510_1817191.html (2021).

Marois, G., Cuaresma, J. C., Zellmann, J. & Reiter, C. A dataset of human capital-weighted population estimates for 185 countries from 1970 to 2100. Scientific Data 11, 612, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03466-y (2024).

Kraay, A. The World Bank Human Capital Index: A Guide. The World Bank Research Observer 34, 1–33, https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkz001 (2019).

UNESCO et al. Methodological Guidelines for Education Sector Analysis, Volume 1 https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/methodological-guidelines-education-sector-analysis-volume-1 (2014).

Ministry of Education of China. A Review of Achievements in Compulsory Education (2012-2021) http://en.moe.gov.cn/documents/reports/202210/t20221022_671525.html (2022).

Kong, M. & Chen, J. in Education in China and the world: Achievements and contemporary issues (eds Liu N., Feng Z. & Wang, Q.) 47–88 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-5861-0_2 (Springer Nature Singapore, 2024).

Gong, P., Zhu, S., Jiang, M., Zhu, B. & Yang, Y. A new dataset of province- and prefecture-level human development index in China. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14744142 (2025).

UNDP. China National Human Development Report 2013 https://www.undp.org/china/publications/china-national-human-development-report-2013 (2013).

UNDP. China National Human Development Report 2016 https://www.undp.org/china/publications/china-human-development-report-2016 (2016).

Cui, H. et al. An evaluation of data accuracy of the 2010 population census of China (in Chinese: 对2010年人口普查数据准确性的估计). Population Research 37, 10–21 (2013).

Barro, R. J. & Lee, J. W. A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. Journal of Development Economics 104, 184–198, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2012.10.001 (2013).

Barro-Lee Educational Attainment Dataset http://barrolee.com/ (2024).

UNDP. Human Development Report 2010 https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2010 (2010).

UNDP. Human Development Report 2023-24 https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2023-24 (2024).

Zhang, S. & Zhu, D. Incorporating “relative” ecological impacts into human development evaluation: Planetary boundaries–adjusted HDI. Ecological Indicators 137, 108786, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.108786 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (24VRC043, 16ZDA009) and the Tsinghua University Initiative Scientific Research Program (2023THZWYY01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.G. and Y.Y. contributed to the methodology development. P.G. and S.Z. contributed to data collection. P.G., S.Z. and M.J. contributed to formal analysis and writing. P.G., B.Z. and Y.Y. supervised the study. All authors (P.G., S.Z., M.J., B.Z. and Y.Y.) were involved in the discussions and approved the manuscript. P.G. and S.Z. contributed equally.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, P., Zhu, S., Jiang, M. et al. A new dataset of province- and prefecture-level human development index in China. Sci Data 12, 1453 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05745-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05745-8