Abstract

Nuclear technology plays a pivotal role in global development, especially as a cornerstone of sustainable innovation. However, nuclear reactions emit high-energy photons and pose significant risks to human health and safety. Accurate radiation hazard assessments are essential for nuclear facilities. The Point Kernel method is widely adopted in safety practice for its high computational efficiency. A key element of this method is the use of coefficients known as buildup factors, which critically impact simulation accuracy. However, the most used dataset—published in the ANSI reports—is outdated in both format and scope, lacking sufficient data to support reliable simulations and hindering further research. To address this limitation, we present a novel open-access dataset, the Photon Shielding Spectra Dataset (PSSD), which provides photon flux shielding spectra with comprehensive elemental coverage. PSSD enhances the adaptability of buildup factors, supports the conversion between multiple physical quantities, and can be seamlessly integrated with advanced AI techniques for improved accuracy and efficiency in radiation safety assessments and shielding design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Radiation safety is a cornerstone of nuclear safety, playing a vital role across domains such as nuclear engineering, space exploration, medical physics, and various industrial applications1. In nuclear facilities, shielding is essential not only because of particles-induced activation structural materials—which leads to the emission of penetrating photon radiation (mostly gamma radiation)—but also because of its direct implications for personnel safety and long-term occupational health2. The effectiveness of shielding design directly affects exposure risks and is thus a critical determinant of facility safety compliance. Furthermore, shielding designs significantly influences the economic efficiency and overall feasibility of facility construction3. As such, accurate modeling of photon interactions with matter is fundamental to optimizing protection while balancing cost and performance. Nonetheless, it is indispensable throughout the entire lifecycle of nuclear applications—including design, construction, commissioning, operation, and real-time monitoring—making it a core component of radiation safety and regulatory strategy4.

As such, accurate modeling of photon interactions with matter is fundamental to optimizing protection while balancing cost and performance. This work is therefore of direct interest to a wide range of specialists, including nuclear engineers designing shielding for reactors and waste storage, medical physicists ensuring nuclear and staff safety during radiological procedures, aerospace engineers protecting astronauts and equipment from cosmic radiation, and AI scientists developing data-driven models for design and analysis of complex nuclear system.

Traditionally, the most widely used approach for simulating radiation transport is based on solving the Boltzmann Transport Equation (BTE)5. This method divides space into discrete units and applies the law of conservation of particles to model the inward and outward flows of particles in each unit. The traditional BTE can be formulated as in Eq. 1, where ψ represents particles flux.

However, solving the BTE is a tough task due to the equation’s dependence on particle flux variations over time t (for a transient problem), angle \(\Omega (\phi ,\theta )\), space D, energy E, and coordinates \(r(x,y,z)\), involving up to seven independent variables, making it computationally intensive6. The deterministic method, which discretizes the equation and divides it into several energy groups, requires the construction of a coefficient matrix. The solution to the resulting system of equations provides the multi-group particle flux. Despite its widespread use, this method requires space and angle homogenization7 and is time-consuming to apply in three-dimensional scenarios, rendering it unsuitable for rapid real-time analysis.

In contrast, the Monte Carlo (MC) method does not directly solve the BTE but leverages the law of large numbers as in Eq. 28,9, which draws distributions. In Eq. 2, Xi represents the final score from a single, complete particle history—for example, the contribution of the i-th particle to the flux in the detector. The simulation is run for n total particle histories. According to the Law of Large Numbers, by averaging the scores from a sufficiently large number of these independent particle histories, the calculated sample mean converges to the true physical quantity μ, which is the expected value of the particle flux.

The method simulates many particle trajectories, considering all detailed physical interactions and continuous cross-sections calculation, making MC the most accurate method10,11,12. However, it requires simulating millions, or even billions, of particles, with a typical simulation involving at least 10 million particles. A major challenge arises in complex shielding scenarios, where particles may not reach points of interest, leading to low estimates and high variance in results. Advanced techniques, such as importance sampling13,14, weighted windows15, and the MAGIC method16, have been developed to mitigate these issues, but MC simulations can still require extensive computation times (often tens or hundreds of hours). As such, it is impractical for real-time simulations, such as rapid risk assessments that nuclear safety needs urgently.

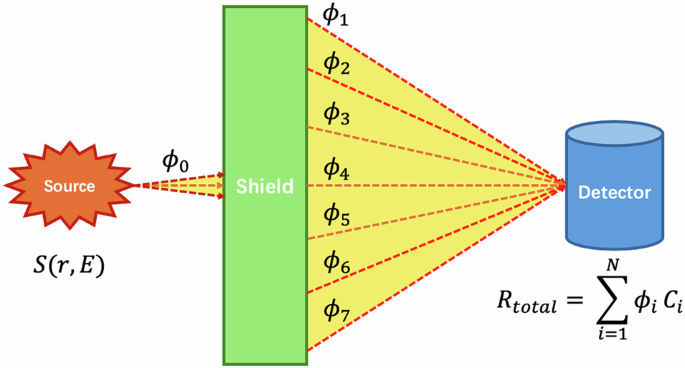

To bridge the gap between the high accuracy of conventional methods and the need for real-time shielding calculations, the Point Kernel (PK) method was introduced17. The PK method simplifies the BTE by reducing it to an attenuation law for photons, rendering the most suitable for nuclear practices. Assuming in total of n energy groups are considered; the PK formulation can be expressed as in Eqs. 3, 4. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between source, scattered flux and responses in shielding analysis18,19.

Fig. 1 illustrates the core concept of the shielding analysis. A source S(r, E) emits photons, resulting in an uncollided flux component \({\phi }_{0}\), that passes directly through the shield. Interactions within the shield also generate a scattered photon field, which is categorized into multiple energy groups (symbolized by \({\phi }_{1}\) through \({\phi }_{7}\)). The total detector response Rtotal is calculated by summing the contributions from all flux components (both uncollided and scattered), where the flux in each group ϕi is weighted by its respective energy-dependent conversion factor \({C}_{i}\).

In Eqs. 3, 4, the subscript k means the k-th energy group of scattered photons. In most cases, source information such as intensity \({I}_{0}\), energy \({E}_{0}\) is readily available, allowing the response at any point in coordinate r to be calculated. The equation divides photon contributions into two components: uncollided flux \(\frac{{I}_{0}({E}_{0})}{4\pi {r}^{2}}{e}^{-\mu r}\), which represents photons that have not interacted along their path (here μ represents linear attenuation coefficient), and scattered flux \({\phi }_{r,k}\), which represents photons that have undergone scattering20. Different from traditional Point Kernel formula, the term \({F}_{r,k}\) represents relative photon flux, which is defined as ratio of \({\phi }_{r,k}\) versus uncollided flux. The physical quantity of interest is modified by a coefficient \(B({E}_{0},r)\) called the buildup factor (BF), which represents the ratio of the total flux response \(R(r,{E}_{0})\) to that of the uncollided fluence21,22. Thus, the accuracy of the PK method depends directly on the accuracy of the BF.

Since the introduction of the PK method, extensive research has been conducted to refine the determination of BF. The most widely used BF dataset, based on the ANSI-6.4.3-1991 report, covers several common shielding materials and 22 elemental substances23. For missing elements, interpolation based on atomic number is used, and existing data is fitted using the Generalized Polynomial (GP) method.

However, the limitations of the ANSI dataset are multi-faceted and significant. Firstly, the ANSI/ANS-6.4.3 standard is critically outdated, with much of its underlying data based on calculations from decades prior that fail to incorporate substantial advancements in nuclear data, physics models, and computational power. Its official withdrawal by ANSI acknowledges its inadequacy for contemporary needs. Secondly, the buildup factors in the ANSI standard were derived using outdated techniques, such as the moment method, which inherently simplify transport physics. This simplification led to the neglect of important physical processes like coherent scattering and bremsstrahlung effects, which can result in a non-conservative underestimation of dose. Thirdly, the ANSI dataset’s scope is severely limited, predominantly providing data for only two dosimetry quantities: exposure and energy absorption buildup factors. This restricts its utility, as the data cannot be adapted for other necessary response functions. Fourthly, the material coverage of the ANSI standard is insufficient for modern applications, providing data for only 22 elemental substances.

The outdated nature of the ANSI dataset has spurred numerous efforts for updates. For instance, research from Tsinghua University24,25, as well as studies in the United States by Lawrence and others, have worked to expand the BF dataset, using the MCNP code and other techniques to calculate BF with more precise simulations26,27. Recent advancements in shielding material research have led to further efforts, such as the use of the Discrete Particle Method combined with Monte Carlo simulations to calculate BFs for materials like lead, tungsten28, and polymer composites29. However, most of these studies are limited to calculations of limited types of materials, within a small range of thickness. Recently, Sun from CAEP conducted Monte Carlo simulations on four commonly used materials with detailed physics models. Thicknesses of up to 100 mean free paths (MFPs) were evaluated, demonstrating that conventional ANSI data tend to underestimate results and further proving the necessity of updating buildup factor (BF) data30. Despite the recognized importance of photon shielding studies, prior research has fallen short of delivering comprehensive coverage across nuclides—primarily due to the prohibitive computational cost of Monte Carlo-based simulations. Even with variance reduction methods in place, the simulation of a single case can take hours, severely limiting scalability. Consequently, the field has long lacked a complete and accessible dataset.

Moreover, existing efforts to update radiation shielding datasets remain largely limited to specific response quantities, such as exposure dose or effective dose estimates. While useful, this level of simplification is increasingly inadequate in the context of rapidly advancing data-driven methodologies. In rapidly advancing fields such as artificial intelligence, researchers have explored the use of AI technologies to achieve faster and more comprehensive representations of original BFs31. However, existing efforts have primarily focused on fitting ANSI-style data, while suffering from insufficient amount and style of training data containing more physics information32,33.

At present, no comprehensive efforts have been made to construct datasets based directly on photon shielding flux spectra. With the rise of artificial intelligence in radiation analysis and design, there is a growing demand for more detailed and continuous field data, rather than single-value data. Such fine-grained spectral data are essential for enabling AI models to learn, generalize, and make accurate predictions across diverse shielding scenarios. Therefore, the structure of shielding datasets must be fundamentally updated—moving toward higher-resolution, spectrum-based representations—to support modern computational tools and improve the fidelity of shielding analysis.

Recognizing the multi-faceted limitations of previous datasets, this work introduces the Photon Shielding Spectra Dataset (PSSD) to provide a modern, comprehensive, and physically robust solution. To resolve the insufficient material coverage and limited scope of the ANSI standard, the PSSD provides full, relative photon flux spectra for the first 92 elements of the periodic table. This spectral format offers superior flexibility, allowing the calculation of diverse dosimetry quantities, while the expanded material coverage meets the needs of modern applications. To correct the outdated and methodologically flawed foundation of previous data, this dataset was generated using the high-fidelity Reactor Monte Carlo (RMC) code, which incorporates detailed photon physics models. The extensive simulations, spanning 22 incident energy points and thicknesses up to 40 MFPs, were conducted on a supercomputing platform, consuming nearly one million CPU core-hours to produce a comprehensive and reliable foundation for advanced nuclear safety analysis.

This work presents three major contributions: (1) It leverages the latest nuclear database and incorporates detailed photon physics models to calculate layered shielding energy spectra for various incident radiation sources. The dataset includes data for 92 nuclides, making it the most comprehensive dataset available for elemental nuclides; (2) The dataset facilitates calculations for a broad range of radiation dosimetry quantities. Unlike previous methods that focused solely on BFs for absorbed dose and exposure dose, the dataset offers superior flexibility and applicability across diverse engineering scenarios; and (3) By providing results as spectral fields rather than single-point values, this work enables a more detailed analysis of energy layers in shielding, offering a new reference for shielding design and calculation, and providing resources for further research integrated with advanced AI technology.

Methods

In this section, we describe the methods used to generate PSSD, as well as a description of high-energy photon generation, the Monte Carlo model used in reactor physics and some basic theory of Monte Carlo calculation. At last, we will have an overview of the process workflow.

Description of photon radiation generation

Photon radiation is mainly generated during the nuclear reactions because of the decay of excited nuclei and activations. During nuclear reaction, a nuclei is often in an excited state and undergoes decay to release energy in the form of high-energy photons. Additionally, gamma radiation is emitted by radioactive isotopes formed through neutron activation within the reactor, such as cobalt-60 and iodine-131. These isotopes can contribute to both direct photon radiation from the nuclear facilities and indirect radiation from materials exposed to the radiation source.

Apart from the direct radiation source, other parts of the nuclear facilities can also produce photon radiation. Take nuclear power plant as example, the coolant, structural materials, and spent nuclear fuel all become activated and can emit gamma photons. Furthermore, radioactive contamination may accumulate in various components, leading to additional radiation exposure. During processes such as spent fuel management and radioactive waste transportation, radiation shielding assessment is essential to protect workers and the environment from harmful exposure.

Theoretical model of RMC

The Reactor Monte Carlo (RMC) code is a powerful simulation tool developed at Tsinghua University. It’s used to solve particle transport problems in nuclear practices using the Monte Carlo method. RMC employs probabilistic sampling techniques to simulate the random interactions of particles, providing detailed insights into particles distributions under distinct conditions. The code tracks particles as they undergo scattering, absorption, and other activities, using detailed cross-section data (as illustrated in Fig. 2, taking three elemental materials’ cross sections plots as examples34) and geometric models of the surrounding structures. A brief description of the theoretical models of key functions of MC method is given12,35.

MC particles transport

Monte Carlo simulation randomly samples the particle’s trajectory in the modeled space. If the macroscopic cross sections \({\varSigma }_{t}\) are known and obey the probability distribution function below:

where the function represents the probability of activity along the trajectory distance of l. After integration and transformation, the sampled distance between two collisions shall be expressed below with \(\xi \) sat uniformly distributed on [0, 1).

Detailed photon physics

RMC incorporate detailed photon physics, including coherent scattering (where photons are scattered without energy loss), incoherent scattering (with energy transfer), Doppler broadening (shifting energy due to atomic motion), photoelectric effect (photon absorption leading to electron emission), pair production (photon converting to an electron-positron pair), and bremsstrahlung (radiation emitted by charged particles accelerating in the presence of an electric field). Some of them are listed in Table 1 for references35. The differential cross-section for Rayleigh scattering can be given by:

and the formula for photon scattering off electrons that is valid for all energies can be calculated using Klein-Nishina formula as below:

and then the differential cross section for incoherent scattering can also be given by:

For photoelectric effect, the incident photon is absorbed by an atomic electron, which is then emitted from the ith shell with kinetic energy as described in Eq. 10.

Based on the model described in Kaltiaisenaho, which models the angular distribution of the photoelectrons using the K-shell cross section derived by Sauter, the non-relativistic Sauter distribution for unpolarized photons can be approximated and used for sampling photoelectric effect:

The bremsstrahlung effect is also described by a cross section that is a differential in photon energy, in the direction of the emitted photon, and in the final direction of the charged particle, which can be expressed in the form:

where \(\kappa =E/T\) is the reduced photon energy and \(\chi (Z,T,\kappa )\) is the scaled bremsstrahlung cross section, which is experimentally measured.

It is important to note how secondary particles are handled in our model. The RMC code performs a coupled photon-electron transport simulation36,37. When primary photons interact via the photoelectric effect, incoherent (Compton) scattering, or pair production, the resulting secondary charged particles (electrons and positrons) are generated and tracked. While the primary goal of this work is to tally the photon flux spectrum, tracking these electrons is crucial for accurately modeling the production of bremsstrahlung radiation. Any bremsstrahlung photons created as these charged particles decelerate in the material are included in the simulation and transported, ensuring a complete and physically accurate photon field.

Shielding calculation model

The shielding calculation model represents an approximately infinite spherical medium of a single material, with an isotropic radiation source located at the center emitting particles of a certain energy, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Concentric spherical surfaces with different mean free path (MFP) values are placed around the source to record the number of particles passing through each layer, allowing for the calculation of dose rates at various distances. As the model simulates an infinite medium, backscattering is considered in the tally process, ensuring conservative results. The model size is set to 45 average free paths for each input, simulating an infinite medium and generating multi-group photon energy spectra for dataset creation.

Though conservative, our use of an infinite medium model is a deliberate choice aligned with the standard, internationally accepted methodology for creating fundamental shielding datasets. The primary goal is to establish a universal standard, and using a finite slab model would introduce geometric dependencies (e.g., the lateral dimensions of the slab) that would make the data specific to that geometry and far less universal. This approach also aligns with established practice, as the infinite medium model is the conventional method for calculating standard buildup factors, including those in the ANSI-6.4.3 report.

To ensure convergence of the calculation results, it is essential to sample enough particles at each layer’s thickness. To achieve this, importance sampling and weighted window methods are employed. These techniques adjust the particle distribution to focus on areas of higher significance, enhancing efficiency. Through multiple iterative calculations, the most optimal weight window parameters are determined. The final calculation undergoes 10 statistical tests to verify its reliability (Table 2), ensuring that the results are robust and accurate. This approach mitigates potential bias and guarantees that the simulation accurately reflects the physical reality of particle transport in the modeled shielding scenario.

Based on the spectral information, and through appropriate transformation from the mass attenuation coefficients of air to flux-to-dose conversion factors, the exposure dose rate buildup factor (EBF) can be derived (Fig. 4), following the approach used in the ANSI standard dataset. The definitions of exposure dose rate and conversion factor are shown in Eqs. 13, 14. The derived EBF will be employed for validation purposes in the subsequent section38,39. In the equations, \({({\mu }_{{en}}/\rho )}_{{air}}\) represents the energy attenuation coefficient of air, e represents quantity of electric charge, and \({W}_{{air}}\) represents The average energy consumed by electrons for each pair of ions formed in dry air, which is 33.85 eV.

Workflow overview

In this study, the RMC program was utilized to generate energy spectrum results for 92 shielding materials40. To address the variance reduction requirement during the computation, several methods, including importance sampling parameters and weight windows, were employed. For materials with significant scattering effects, traditional variance reduction techniques were insufficient. Therefore, energy truncation and distribution-based methods were applied to accurately calculate the energy spectra.

The overall computational workflow for generating the shielding material dataset is illustrated in Fig. 5. First, the RMC program is initialized with mean free path calculated on-the-fly to decide size of the shielding model. Upon initialization, material cross-section data is read, and input files are constructed based on the material properties and energy group configurations. For each material, the script automatically iterates to adjust the importance sampling parameters and weight window settings, optimizing the computational process. The overall simulations were carried out on a supercomputing platform, consuming nearly one million CPU core-hours, to draw reliable results for further research and applications.

To address the variance reduction requirement for this deep penetration problem, several methods were employed. Specifically, we utilized the CADIS (Consistent Adjoint Driven Importance Sampling) methodology41,42. CADIS is an automated technique that uses a deterministic adjoint transport calculation to generate an importance map. This map is then used to create the weight windows and biased source parameters needed for the main Monte Carlo simulation. This process ensures that computational effort is focused on particles that are most likely to contribute to the tallies at deep penetration depths, making an otherwise intractable calculation feasible and efficient.

Once the necessary parameters are configured, the RMC simulations are run to compute the energy spectra for each material. For materials with strong scattering effects, energy truncation and distribution-based methods are employed to ensure reliable results. The simulation outputs are then subjected to a series of statistical checks (listed in Table 2) to validate the accuracy and conservativeness of the results. Figure 6 illustrates the structure of Input file of RMC.

Data Records

The complete Photon Shielding Spectra Dataset (PSSD)43 is publicly available in the Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28930319). As illustrated in Fig. 7, the repository is organized into separate directories for each element, named by its chemical symbol. Each directory contains the raw tallied output files generated by our high-fidelity simulations. For reference and validation, the repository also includes conventional data from the ANSI/ANS-6.4.3 standard; this reference data can be independently verified through published literature or calculated using open-source tools such as the PAGEX44 software (https://github.com/sriharijayaram5/PAGEX).

PSSD framework: the data record43.

To facilitate the use of the data, we employed Python scripts to extract and preprocess the raw data. The extracted files include several types of information: the original flux data, flux data with non-collision contributions excluded, and data that has been normalized and supplemented with cross-section information. These files cater to a wide range of user needs, providing access to both raw and processed data in a form that can be used for further analysis.

Each nuclide’s directory contains a structured set of files, which can be accessed directly for analysis or further processing. The dataset provides flexibility, with raw data for users requiring unprocessed information, as well as normalized data that incorporates relevant cross-section data for those interested in more advanced applications. The dataset is stored on Figshare, ensuring easy access and version control, making it available for the broader research community.

Technical Validation

Since the application of nuclear power, the radiation shielding is one of the main concern to be addressed because of the harm and consequences that might be caused without proper precautions strategies. In the past, for engineering application, the Point Kernel method is so widely used in the field of engineering. Through lots of experiments, newly developed datasets have also been drawn to make full uses of data for simulating radiation transport along the whole space. The conventional ANSI dataset utilized outdated database and did not consider all physics processes like coherent scattering and bremsstrahlung effect, which may cause under estimation of the buildup factor. Moreover, traditional buildup factors are overly simplified, since the cause of dose sterns from particle flux, which is a transport problem, making use of the idea of deterministic method, to inflating buildup factors back into flux information appears to be more reasonable.

In this section, the exposure buildup factor (EBF), which has been seen as the most widely used on in engineering scenarios, has been calculated with the newly developed dataset, The EBF calculated have been compared with that of ANSI-6.4.3-1991 data, to validate the trend and value which are supposed to be consistent with those of our data. Then, the visualization of our data has been carried out for having a clearer view of the particle flux distribution results along 40MFPs, which shall be further analyzed to draw the physical conclusion about photon transport problems in different kinds of materials, setting references to future works concerning radiation shielding calculation in sight of detailed physics.

Validation using the ANSI report Data

The MC simulation was validated against the ANSI-6.4.3-1991 dataset, which is still deemed as the official dataset for many conventional Point Kernel codes like QAD and MicroShield. The calculation method used in ANSI/ANS6.4.3-1991 can be separated into two types, which are moment method, for calculating low-Z elements including Be, B, C, N, O, Na, Mg, Al, Si, P, S, K, Ca, Fe, Cu. The nuclear database used for low-Z buildup factors calculation was the NBS29 database. Afterwards, based on discretized-coordinates method, elements like Mo, Sn, La, Gd, W, Pb, U were calculated with PHOTX database. For both cases, certain photon physics process like coherent scattering and bremsstrahlung effect were ignored.

This methodological split was a direct consequence of the computational limitations and physical complexities of the era in which the data was generated. For low-Z elements, where Compton scattering is dominant, the computationally efficient moment method was used, but it inaccurately neglected both coherent scattering and bremsstrahlung effects. For high-Z elements, where complex photoelectric effects and secondary radiation are critical, the more robust but far more expensive discretized-coordinates method was required. Even so, this method also ignored coherent scattering, and both approaches relied on outdated nuclear data. This inconsistent, dual-methodology approach, with its significant physical omissions, created a fundamentally incomplete dataset and underscores the need for the modern, comprehensive simulation work presented here.

Our dataset takes all detailed physics into consideration, while using the latest cross section library ENDF/B-VIII.0 as the main calculation basis, to carry out reasonable photon results throughout in total of 40 MFPs’ thickness45. Since exposure is an important concern in nuclear industry, the EBF of the above mentioned 22 nuclides are calculated using relative flux data calculated earlier and mass flux conversion factors calculated shown in Fig. 4 as comparisons against the original ANSI/ANS6.4.3-1991 data. For abbreviation, in this paper, the representative 6 elements, C, O, Al, Fe, Mo, Pb are presented here44, to show the variation trend of EBF in both datasets.

EBF of C

The Fig. 8 shows the EBF variation curves of element carbon with different incident photon energies. It’s worth noting that, when ANSI first planed the calculation of BUFs, only the moment method was used without considering coherent scattering and bremsstrahlung effect that could take place during particle transport. However, coherent scattering is especially vital for low-Z elements, where incident photon energy is relatively low. As can be seen in the figure, with low incident energy input, the calculated EBF are extremely high because of scattering of low-energy particles. When incident photon energy is higher, the photons’ processes stronger penetration abilities, making less generation of low-energy particles, leading to lower BUFs calculated. Either ways, when using our newly established dataset, the conservatism is achieved, which is necessary for PK algorithm.

EBF of O

The Fig. 9 shows the EBF variation curves of element oxygen with different incident photon energies. Like carbon, oxygen also exhibits a noticeable trend where the gap between the ANSI data and our calculated results is larger at low incident energies. This suggests that the impact of incoherent scattering and bremsstrahlung radiation becomes more significant at lower energies. The discrepancy at low energies can be attributed to the increased scattering of low-energy particles, which the ANSI method did not account for, as it only utilized the moment method without considering the additional effects of scattering and bremsstrahlung radiation. Our calculation, however, incorporates these physical phenomena, providing a more accurate representation. Despite this, our results still maintain a conservative approach, ensuring that the calculated BUFs are within safe bounds, which is crucial for the PK algorithm to guarantee reliability and robustness in complex geometries. This careful balance between physical accuracy and conservatism in our dataset contributes to the overall integrity of the shielding calculations.

EBF of Al

The Fig. 10 shows the EBF variation curves of element aluminum with different incident photon energies. As with oxygen, our results for aluminum generally follow the same trend as the ANSI data. However, at low incident energies, the discrepancy in the calculated accumulation factors becomes more pronounced. This can be attributed to the effects of coherent scattering and the differences in the cross-section libraries used in our calculations. While the ANSI method relied on simpler models, our approach incorporates a more refined treatment of scattering processes, leading to differences in the low-energy range. Nevertheless, our calculations continue to ensure conservatism, aligning with the necessary safety requirements for the PK algorithm. This guarantees that the results remain within an acceptable range, even when accounting for more detailed physical effects like coherent scattering.

EBF of Fe

The Fig. 11 shows the EBF variation curves of element iron with different incident photon energies. Compared to the ANSI data, our results show a significantly higher increase in the low-energy range, with values more than ten times greater than the previous data. The ANSI method is generally more conservative in this case, but our calculations provide a more accurate representation by considering additional physical effects such as coherent scattering. This increase at low energies is consistent with the improved accuracy of our model, while still ensuring that the results remain conservative enough for the PK algorithm.

EBF of Mo

The Fig. 12 shows the EBF variation curves of element molybdenum with different incident photon energies. Starting from Mo, the ANSI data employs a discrete ordinate method and includes bremsstrahlung effects. However, it still does not account for the dominant coherent scattering at low energies, leading to a significant discrepancy in the low-energy range. Our new data, on the other hand, incorporates both coherent scattering and bremsstrahlung effects, providing more accurate results. Despite this, our calculations maintain a higher level of conservatism, ensuring safe and reliable shielding predictions.

EBF of Pb

The Fig. 13 shows the EBF variation curves of element lead with different incident photon energies. At 0.1 MeV and 40 MFP, both the original and new data show identical trends, with the new data being more conservative. As the depth increases, the curves of the original and new data converge, indicating consistency between the two sets of results at deeper depths. Overall, the calculated results exhibit strong performance, both in terms of trend alignment and conservatism, ensuring the reliability and safety of the shielding calculations.

Data distribution analysis

Another important discussion pertains to the energy groups in which the flux is categorized. Given that the newly developed dataset includes multigroup flux data for the exit photons, it is essential to analyze the distribution patterns and characteristics of these flux. In this context, the relative flux—defined as the flux rate within a specific energy bin relative to the uncollided flux rate—has been examined after a logarithmic transformation. Additionally, analyses have been performed for selected representative elements. To investigate the relative magnitude between uncollided flux and spectral flux, the relative flux shall be derived as in Eq. 15.

Overall relative flux distribution of all data

The Fig. 14 illustrates the overall distribution of relative flux, which represents the ratio of the actual flux rate within a specific energy range to the flux rate of uncollided photons. This relative flux can be used to analyze and visualize the effects of scattering and the likelihood of specific photon-matter interactions at different energy levels. As depicted in the figure, the relative flux rate is notably higher for exit photons with lower energies, where scattering is dominant in these regions. As the atomic number increases, the peak shifts from left to right, indicating that the cumulative energy range is influenced by the distribution of reaction cross-sections for specific elements. Notably, at energies near 1.022 MeV and 2.044 MeV, the relative flux is minimal, which corresponds to high absorption probabilities due to pair production effects.

Overall distribution of relative flux with different input settings. The data is ordered systematically along this y-axis: primarily by elemental atomic number (from low to high), then by shielding thickness, and finally by incident photon energy (from low to high). This heatmap visualizes how the relative flux spectrum (x-axis) changes across all configurations, with the color indicating the log-normalized flux.

Relative flux distribution of single element with respect to thickness

The dataset also includes the relative flux distribution of a single element with respect to thickness, when the incident photon energy is constant, as in Fig. 15.

Relative flux distribution of Fe with respect to thickness. Each of the individual subplots in this grid corresponds to a different, constant incident photon energy, ranging from 0.1 MeV to 10 MeV. Within each subplot, the x-axis represents the shielding thickness in Mean Free Paths (MFP), the y-axis represents the energy of the output photons, and the color indicates the log-normalized flux intensity.

The dataset encompasses 92 elements, each with multiple photon energy spectra, incident energies, and thickness parameters, resulting in over 30,000 data points that cannot all be displayed here. For illustration, we have selected iron (Fe) as a representative example. The figure presents the relative flux distribution of different output photon spectra as a function of material thickness, with incident energy held constant. The distribution generally follows an exponential decay pattern, characteristic of particle transport in shielding materials. Furthermore, a distinct electron slowdown effect is observed, where certain energy ranges exhibit clustering, reflecting the reduced velocity of particles at lower energies.

Relative flux distribution of single element with respect to exit photons energy

Finally, regarding the relative flux distribution of a single element in relation to exit photon energy, the Fig. 16 illustrates the distribution of photon spectra at various layers for different incident energies, with thickness held constant. Iron (Fe) is again selected as the representative example. The results indicate that the peak of the relative photon flux distribution for Fe tends to occur at deeper layers, with lower incident photon energies being more likely to produce these peaks. This can be attributed to the increased interaction of low-energy photons with the material, leading to a higher concentration of scattered photons at greater depths.

Usage Notes

The dataset is distributed in its original output format generated by the Reactor Monte Carlo (RMC) code, with a total size of approximately 10.0 GB. To minimize storage requirements, a pre-processing step was carried out to convert the original output into a more compact raw data format. A detailed description of the dataset, along with Python scripts for data reformatting, is available in the dataset’s Figshare repository.

Although users may regenerate the dataset using RMC, this approach is not recommended due to the significant computational cost and time involved. Instead, it is advisable to utilize the pre-processed dataset directly. Users are also encouraged to use this dataset as a foundation for constructing customized datasets tailored to AI model development. To support data exploration and analysis, additional Python scripts for visualization are provided as well.

A key intended use of this dataset is to serve as a foundation for advanced AI-driven applications in radiation safety. The primary advantage of the PSSD43 over conventional datasets is its rich, high-resolution spectral format. Historically, AI applications in this field were restricted to simple fitting tasks (e.g., using MLPs) because datasets like the ANSI standard contained only single-value buildup factors, lacking detailed physical information. Our dataset provides the full photon flux spectra of all 92 elements, offering a much higher-dimensional and more physically informative basis for model training. This leap in data quality enables and necessitates more sophisticated architectures; for instance, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can analyze the spectra to learn physical features automatically, while generative models could be trained to predict high-fidelity spectra for novel shielding scenarios. This fosters a coupled evolution where better data demands and unlocks more powerful AI tools for deeper insights into radiation transport.

Code availability

These simulations were conducted using RMC (https://rmc-doc.reallab.org.cn/). The data processing step was performed using scripts written in the Python 3.10 compiler. More about this dataset can be found on the dataset’s Figshare page (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28930319).

References

Shultis, J. K. & Faw, R. E. Radiation Shielding Technology. Radiat. Shield. Technol. Heal. Phys. 88, 587–612 (2005).

Gu, Z. History review of nuclear reactor safety. Annals of Nuclear Energy 120, 682–690 (2018).

Shultis, J.K, Faw, R. Radiation Shielding. American Nuclear Society Inc, Illinois. (2000a).

Clarke, R.H, J. Dunster, C. H, K. Guskova, L. A & S. Taylor, A. L. Annals of the ICRP Published on behalf of the lnternational Commission on Radiological Protection Members of the Main Commission of the ICRP (1991).

Askew, J. R. A Characteristics Formulation of the Neutron Transport Equationin Complicated Geometries. AAEW-M 1108. UK Atomic Energy Establishment (1972).

William, B., Samuel, S., Lulu, L., Benoit, F. & Kord, S. The OpenMOC method of characteristics neutral particle transport code. Annals of Nuclear Energy 68, 43–52 (2014).

Nhan, N. T. M., Kyeongwon, K. & Deokjung, L. Modelling atomic relaxation and bremsstrahlung in the deterministic code STREAM. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 56(2), 673–684 (2024).

Paul, K. R., Nicholas, E. H., Bryan, R. H., Benoit, F. & Kord, S. OpenMC: A state-of-the-art Monte Carlo code for research and development. Annals of Nuclear Energy 82, 90–97 (2015).

Brown, F. B, Kiedrowski, B, Bull, J. MCNP5-1.60 release notes. LA-UR-10-06235, Los Alamos National Laboratory (2010).

Leppanen, J. Serpent - A Continuous-energy Monte Carlo Reactor Physics Burnup Calculation Code, User’s Manual. VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland (2012).

Wang, K, et al Reactor Monte Carlo code RMC: The state-of-the-art technologies, advancements, applications, and next, EPJ - Nuclear Sciences & Technologies, 10 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. RMC – A Monte Carlo code for reactor core analysis. Annals of Nuclear Energy 82, 121–129 (2015).

Pan, Q., Rao, J., Huang, S. & Wang, K. improved adaptive variance reduction algorithm based on RMC code for deep penetration problems. Ann. Nucl. Energy 137, 107113 (2020).

Pan, Q., Wang, L., Cai, Y., Liu, X. & Xiong, J. Density-extrapolation global variance reduction (DeGVR) method for large-scale radiation field calculation. Comput.Math. Appl. 143, 10–22 (2023).

Pan, Q., Tang, H., Xiong, J. & Liu, X. Pointing probability driven semi-analytic Monte Carlo Method (PDMC) - Part I: Global variance reduction for large-scale radiation transport analysis. Comput. Phys. Commun. 291, 108850 (2023).

Hu, Y., Qiu, Y. & Fischer, U. Development and benchmarking of the Weight Window Mesh function for OpenMC. Fusion Engineering and Design 170, 112551 (2021).

White, R. The penetration and diffusion of Co60 Gamma-rays in water using spherical geometry. Phys. Rev. 80, 154 (1950).

Harima, Y. Validity of the geometric-progression formula in approximating Gamma-ray buildup factors. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 94, 24–35 (1986).

Trubey, K New Gamma-Ray Buildup Factor Data for Point Kernel Calculations: ANS-6.4.3 Standard Reference DATA, Technical Report, ORNL, Office of Administration and Resources Management, Washington. D. C. 20555 (1988).

Kalos, K. Technical Report, Nuclear Development Associate (NDA) (1956).

Bowman, A., Trubey, K. Technical Report, ORNL, Oak Ridge Natl.Lab (1958).

Broder, L., Kayurin, P. & Kutuzov, A. Transmission of Gamma radiation through heterogeneous media. Sov. J. At. Energy 12, 26–31 (1962).

ANSI/ANS. Gamma ray attenuation coefficient and buildup factors for engineering materials. Gamma-Ray Attenuation Coefficients and Buildup Factors for Engineering Materials (1991).

Li, H, Liu, L, Xia, S. Research of New Gamma-Ray Buildup Factor Data and Its Influence Factors for Point Kernel Calculations. The Eighth International Symposium on Radiation Safety and Detection Technology (ISORD-8). Oral report, Korea, July 13-16, 2015.

Lawrence, P. R. & Charlotta, E. Update to Ansi/ans-6.4.3-1991 Gamma-ray Buildup Factors for High-z Engineering Materials (part I). Transactions of the American nuclear society 99, 618–620 (2008).

Shimizu, A. & Hirayama, H. Calculation of gamma-ray buildup factors up to depths of 100 mfp by the method of invariant embedding (ii): Improved treatment of bremsstrahlung. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 40, 192–200 (2003).

Shimizu, A. Calculation of gamma-ray buildup factors up to depths of 100 mfp by the method of invariant embedding (i). J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 39, 477–486 (2002).

Sardari, D., Baradaran, S., Mofrad, F. B., Marzban, N. Monte Carlo calculation of buildup factors for 50 keV–15 MeV photons in tungsten up to 15 mean free paths. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 183 (2022).

Karimi-Shahri, K., Rezaei Moghaddam, Y., Akhlaghi, P., Mohammadi, N. & EbrahimiKhankook, A. A Comprehensive study of the exposure and energy absorption buildup factors in some polymer composites for point isotropic Source, including the effect of bremsstrahlung. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms 557, 165552 (2024).

Sun, P., Xing, L., Yin, L., Huang, J. & Ying, Y. Calculation of Gamma-Ray buildup factors up to 100 MFP by the Monte Carlo method. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 233, 112696 (2025).

Caracena, M., Vidal, V., Goncalves, G. & Peerani, P. A KD-trees based method for fast radiation source representation for virtual reality dosimetry applications in nulcear safeguards and security,. Prog. Nucl. Energy 95, 78–83 (2007).

Kucuk, N. Computation of Gamma-ray exposure buildup factors up to 10 mfp using generalized feed-forward neural network. Expert Syst. Appl. 37, 3762–3767 (2010).

Chen, R., Cammi, A., Seidl, M., Juan, M. & Wang, X. Computation of Gamma-ray exposure buildup factors based on backpropagation neural network. Expert Syst. Appl. 177, 115004 (2021).

Hubbell, J. H., Seltzer, S. M. Tables of x-ray mass attenuation coefficients and mass energy-absorption coefficients from 1 keV to 20 MeV for elements Z = 1 to 92 and 48 additional substances of dosimetric interest. NIST Standard Reference Database 126 (2004).

Grady, H. H. An Electron/photon/relaxation Data Library for MCNP6. LA-UR-13-27377 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Development of shutdown dose rate calculation code based on cosRMC and application to benchmark analysis. Fusion Engineering and Design 173, 112846 (2021).

Zhang, X., Liu, S., Yan, Y., Qin, Y. & Chen, Y. Application of the neutron-photon-electron coupling transport of cosRMC in fusion neutronics. Fusion Engineering and Design 159, 111875 (2020).

ICRP Publication 116. Conversion coefficients for radiological protection quantities for external radiation exposures. In: Conversion Coefficients for Radiological Protection Quantities for External Radiation Exposures, 116. ICRP Publication (2012).

Hubbell, J. H, Seltzer, S. M. B. XCOM: Photon Cross Sections Database (2005).

Zhang, X., Liu, S., Wang, Z. & Chen, Y. Development of unstructured mesh tally capability in cosRMC and application to shutdown dose rate analysis. Fusion Engineering and Design 181, 113211 (2022).

Che, R., Liu, S., Tian, Z. & Chen, Y. Verification of shielding calculation capability of cosRMC with SINBAD fusion benchmarks. Fusion Engineering and Design 203, 114465 (2024).

Wang, S., Liu, S., Wu, J. & Chen, Y. Analysis of transport-activation internal coupling method implemented in Monte Carlo code cosRMC. Fusion Engineering and Design 202, 114395 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Photon Shielding Spectra Dataset (PSSD). Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28930319 (2025).

Prabhu, S., Jayaram, S., Bubbly, S. & Gudennavar, S. A simple software for swift computation of photon and charged particle interaction parameters: PAGEX. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 176, 109903 (2021).

Brown, D. A., Chadwick, M. B. & Capote, R. ENDF/B-VIII.0: The 8th Major Release of the Nuclear Reaction Data Library with CIELO-project Cross Sections, New Standards and Thermal Scattering Data. Nuclear Data Sheets 148, 1–142 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Junyi Chen: methodology, implementation, data curation, writing – original draft preparation. Chenghao Cao: data processing, technical validation, writing – review & editing. Shaoning Shen: data processing, technical validation, writing. Ruihan Li: data processing, data curation. Ben Qi: data processing, data curation. Jingang Liang: conceptualization, resources, supervision, writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Cao, C., Shen, S. et al. A Simulated Comprehensive Photon Flux Shielding Spectra Dataset for Advanced Radiation Safety Assessment. Sci Data 12, 1498 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05814-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05814-y