Abstract

The leaf wax layer in cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. Botrytis L.) and other Brassica crops play an important role in environmental adaptation and defense. Here, high-throughput RNA sequencing was performed on leaves of a wax-deficient mutant type (WL) and its wild type (YL). A total of 43.13 Gb of raw RNA-seq data was obtained, of which 42.38 Gb of high-quality clean reads were retained after quality control. A total of 24,529 genes and 1,092 long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) were identified through transcriptome assembly and annotation. Functional enrichment analysis indicated that these mRNA and lncRNA are associated with biotic stress responses, lipid biosynthesis, and fatty acid degradation pathways. This study provides valuable transcriptomic resources for the wax deficiency of cauliflower and lays a foundation for future research on genetic improvement and breeding strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. Botrytis L.) is a cultivated variety of B. oleracea, belonging to the family Brassicaceae, it was domesticated from wild cabbage through selective breeding1,2,3. In recent years, cauliflower production has faced increasing challenges from multiple diseases, including black rot (Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris), downy mildew (Hyaloperonospora parasitica), black spot (Alternaria brassicicola), soft rot (Pectobacterium spp.), various viral infections, and clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae), which are known to adversely affect both yield and quality4,5,6. Therefore, there is a critical need to enrich cauliflower germplasm diversity and develop cultivars with enhanced resistance to pests and diseases. However, prolonged artificial selection in breeding programs has progressively reduced the genetic diversity of resistance genes in current breeding lines, limiting the development of highly resistant cauliflower cultivars3. Identification of disease-resistant materials and associated resistance genes is essential for breeding cauliflower varieties with enhanced resistance7. In particular, the leaf cuticular wax layer has been reported to serve as a key physical barrier against pathogen entry, playing an important role in plant defense8,9. Among various plant defense mechanisms, the cuticular wax layer on leaves has been shown to act as a physical barrier that reduces pathogen invasion, and its association with disease resistance has been reported in maize10, tomato11, cassava12, and rapeseed13. In addition, plants with higher leaf wax content exhibit greater drought resistance than those with lower wax accumulation14,15,16. Leaf wax is primarily composed of compounds such as fatty acids, alcohols, ketones, and esters, and its biosynthesis is regulated by complex metabolic pathways, as shown in previous studies17,18. Modulating the expression of wax biosynthetic genes enhances cuticular wax deposition on the leaf surface, thereby strengthening the plant’s physical barrier against environmental stresses.

To date, most genomic studies on cuticular wax biosynthesis have focused on Arabidopsis thaliana, where over 190 genes involved in wax biosynthesis and transport have been identified18,19,20, and AtCER1 and AtCER4 have been well characterized as key genes involved in wax biosynthesis in leaves21,22,23,24. In Brassica rapa, the CER1 gene has been implicated in the regulation of cuticular wax biosynthesis25. In Brassica napus, another member of the Brassicaceae family, the wax-related gene BnWIN2CO1 shows significantly different expression between wild-type and wax-deficient mutant plants26. This gene participates in several signaling pathways, including those associated with biotic and abiotic stress responses and abscisic acid biosynthesis27,28,29. However, studies on wax-related regulatory genes in cauliflower have not yet been reported.

Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) are transcripts longer than 200 bp that lack a long open reading frame (ORF) and have no protein-coding potential. In plants, lncRNA serves as key regulators of gene expression, and participate in diverse biological processes such as growth, development, and responses to environmental stress30,31. It exerts its regulatory functions through multiple mechanisms, such as transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation, as well as epigenetic modifications involving DNA methylation, antisense transcription and histone modification32,33. In cauliflower, lncRNA plays regulatory roles in transcription and may also participate in post-transcriptional gene regulation through interactions with miRNA34. However, the regulatory mechanism of lncRNA in wax deficiency in cauliflower has not yet been reported. In this study, based on the breeding process of cauliflower germplasm resources, a wax-deficient mutant plant and its sister lines were selected. This study provides scientific evidence for the localization and cloning of wax-related genes, establishes a theoretical foundation for elucidating the disease resistance mechanisms associated with cauliflower wax, and offers valuable insights for future research on genetic mechanisms, genetic improvement and breeding strategies.

Methods

Sample collection

Two cauliflower lines were obtained from the Institute of Tropical Eco-agriculture, Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Yuanmou, Yunnan, China. The wax-deficient mutant cauliflower (12-2-1, WL) and the wild-type (12-2-2, YL) are sister cauliflower varieties (Fig. 1). All seedlings were grown in a greenhouse under a 14 h light/10 h dark cycle at 25 °C during the light period and 20 °C during the dark period. Leaf tissues were collected from 30-day-old seedlings and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80 °C, with three biological replicates per sample.

RNA extraction and library preparation

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen), and its concentration, purity, and integrity were assessed with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Three micrograms of high-quality RNA were used for library preparation. mRNA was enriched using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads and fragmented in Illumina proprietary buffer under elevated temperature. First-strand cDNA was synthesized with random primers and SuperScript II, followed by second-strand synthesis using DNA Polymerase I and RNase H. After end repair and 3′ adenylation, Illumina PE adapters were ligated. Fragments of 400–500 bp were selected using the AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, CA, USA), and the adapter-ligated DNA was enriched by 15 cycles of PCR. Final libraries were purified, quantified using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Fig. S1), and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 4000 platform (150 bp paired-end reads) by Panomix Biomedical Tech Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China).

Quality control

Raw data were subjected to quality control and filtration using Fastp (version 0.24.0)35. The first 13 bases from the 5′ end of forward and reverse reads were removed, low-quality bases (Q < 20) were trimmed, and reads shorter than 15 bp were discarded using the default settings. Finally, the quality of the trimmed and filtered reads was reassessed with FastQC (version 0.11.9) (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) (Fig. S2). All downstream analyses were performed based on high-quality clean reads.

Transcriptome analysis workflow

The clean reads were then aligned to the reference genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_000695525.1/) using Hisat2 (version 2.2.1)36. Then, the SAM files output from Hisat2 were sorted and converted to BAM files using Samtools (version 1.21). Finally, the gene read counts were calculated using FeatureCounts program (version 2.1.0)37, and gene expression levels (FPKM, Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) were calculated using Perl scripts. These genes were retained if they had FPKM > 0.5 in at least two replicates of a sample.

A total of 43.13 Gb of raw sequencing data was generated, from which more than 42.38 Gb of high-quality clean reads were retained after quality filtering, corresponding to approximately 285 million reads. The filtered reads exhibited quality scores of over 98% at Q20 and over 95% at Q30, with GC content ranging from 46.56% to 47.41% (Table 1).

A bioinformatics pipeline for lncRNA

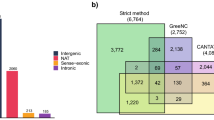

To identify lncRNA transcripts, novel transcript assemblies were generated and subsequently merged (-F 0 -T 0) using Stringtie (version 2.2.3)38 and Gffcompare (version 0.12.9)39. Additionally, multiple filtering criteria were applied to retain accurate lncRNA loci information. First, new transcripts classified as “i, u, p, x” with no coding potential were selected. Second, transcripts shorter than 200 bp were excluded. To predict the protein-coding potential of candidate lncRNA transcripts, six computational approaches were used: CPC2 (score < 0.5)40, CNCI (score < 0)41 and LGC42, and the open reading frames (ORF) length using OrfPredictor (ORF < 300 bp)43, and BLAST against the Pfam (https://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/Pfam/)44 and SwissProt (https://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/uniprot)45 protein databases that were used to predict candidate lncRNA transcripts protein-coding ability. Finally, expression levels were also considered, and lncRNA with an FPKM > 0.5 in at least two samples were retained.

A total of 1,092 lncRNA were identified using CPC2, CNCI, LGC, and OrfPredictor, in combination with homology searches against the Pfam and SwissProt protein databases (Fig. 2, 3a). Firstly, the length of lncRNA was shorter compared to mRNA (Fig. 3b). Then, the average transcript length of lncRNA was 1,112.65 bp (median: 445 bp), whereas the average length of mRNA was 1,687.56 bp (median: 1,493 bp). In addition, lncRNA contained fewer exons than mRNA, with a maximum exon number of 6 (Fig. 3c).

Data Records

The raw sequencing data have been deposited in NCBI under the BioProject accession number PRJNA118890446, Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accessions SRR31445557, SRR31445558, SRR31445559, SRR31445560, SRR31445561, SRR31445562. In the NCBI database, the sample names are labeled as MT and WT. For clarity, in our study, WL represents the MT sample (WL1, WL2 and WL3 corresponding to MT1, MT2 and MT3, respectively), while YL represents the WT sample (YL1, YL2 and YL3 corresponding to WT1, WT2 and WT3, respectively).

Technical Validation

Biological repetition

In this study, to improve the reliability of the results, samples were collected in three biological replicates.

Assessment of the quality of mRNA and lncRNA

In this study, a transcriptome assembly of cauliflower was performed. In total, 24,529 expressed genes were identified and included for subsequent analyses (Fig. 4 and Table S1). To assess the reliability and reproducibility of the transcriptome data, correlation analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) were conducted based on the expression profiles of all detected genes (Fig. 5a,b). Interestingly, the expressed genes in the WL and YL samples exhibited obvious dispersion. Similarly, we performed correlation and PCA analyses on the 1,092 expressed lncRNA (Table S2), the results demonstrated high reproducibility among the samples (Fig. 5c), with PCA1 and PCA2 accounting for 28.2% and 21.4% of the total variation, respectively (Fig. 5d). In summary, the expression levels of mRNA and lncRNA were significantly different between the WL and YL samples.

Functional annotation and enrichment analysis

Further information on the differentially expressed analysis, functional annotation and enrichment analysis of mRNA and lncRNA, including detailed methods, analysis results and datasets has been uploaded to Figshare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27727356)47.

Usage Notes

This dataset46 was generated from a collection of wax-deficient cauliflower lines. Under natural growth conditions, wild-type cauliflower leaves have a wax layer (YL, 12-2-2), whereas the wax-deficient cauliflower (WL, 12-2-1) is a naturally occurring mutant identified during breeding selection without any artificial intervention. The wax layer plays a crucial role in cauliflower growth and development, particularly in plant immunity and defense mechanisms. This dataset provides valuable insights into the relationship between wax deficiency and plant resistance during the natural breeding process of cauliflower.

Code availability

In this study, data processing and analysis were used R software (v4.4.0), and all the code was publicly available. Additionally, this code of figure is available at https://github.com/kanghuadu/Transcriptomics_Figure.

Parameters for the software tools involved are described below:

(1) Fastp: version 0.24.0, parameters: -f 13 -F 13 -q 20;

(2) FastQC: version 0.11.9, default parameters;

(3) Hisat2: version 2.2.1, parameters: -p 20 --dta --min --intronlen 20–max-intronlen 500000 --minins 0 --maxins 500;

(4) Samtools: version 1.21, default parameters;

(5) StringTie: version 2.2.3, default parameters; --merge, parameters: -F 0 -T 0;

(6) Gffcompare: version 0.12.9, default parameters;

(7) FeatureCounts: version 2.1.0, default parameters;

References

Chen, R. et al. Genomic analyses reveal the stepwise domestication and genetic mechanism of curd biogenesis in cauliflower. Nat Genet 56, 1235–1244 (2024).

Mabry, M. E. et al. The Evolutionary History of Wild, Domesticated, and Feral Brassica oleracea (Brassicaceae). Mol Biol Evol 38, 4419–4434 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Breeding a novel cauliflower with exceptional fragrance. Mol Hortic 5, 56 (2025).

Hou, Q. Y. & Ming, G. Z. Cauliflower main disease control technology. Plant Doctor 30, 60–61 (2017).

Kanna, G. P. et al. Advanced deep learning techniques for early disease prediction in cauliflower plants. Sci Rep 13, 18475 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Identification of black spot resistance in broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica) germplasm resources. Appl Sci 14, 2883 (2024).

Yao, X. et al. Study on the changes of miRNAs and their target genes in regulating anthocyanin synthesis during purple discoloration of cauliflower curd under low temperature stress. Front Plant Sci 15, 1460914 (2024).

Kunst, L. & Samuels, A. L. Biosynthesis and secretion of plant cuticular wax. Prog Lipid Res 42, 51–80 (2003).

Herzig, L. et al. In a Different Light: Irradiation-Induced Cuticular Wax Accumulation Fails to Reduce Cuticular Transpiration. Plant Cell Environ 48, 3632–3646 (2025).

Javelle, M. et al. Overexpression of the epidermis-specific homeodomain-leucine zipper IV transcription factor Outer Cell Layer1 in maize identifies target genes involved in lipid metabolism and cuticle biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 154, 273–86 (2010).

Kang, L. G., Qi F, K., Xu, X. Y. & Li, J. F. Relationship between Tomato Leaf Wax and Cutin Layers with Infection by Helminthosporium carposaprum. Chinese Vegetable 18, 47–50 (2010).

Zinsou, V., Wydra, K., Ahohuendo, B. & Schreiber, L. Leaf waxes of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) in relation to ecozone and resistance to Xanthomonas blight. Euphytica 149, 189–198 (2006).

Wang, J., Liu, H. L., Song, C. & Ni, Y. Relationship between brassica napus epicuticular wax composition and structure and resistance to sclerotinia sclerotiorum. J Plant Physiol 48, 958–964 (2012).

Smirnova, A., Leide, J. & Riederer, M. Deficiency in a very-long-chain fatty acid β-ketoacyl-coenzyme a synthase of tomato impairs microgametogenesis and causes floral organ fusion. Plant Physiol 161, 196–209 (2013).

Pu, Y. et al. A novel dominant glossy mutation causes suppression of wax biosynthesis pathway and deficiency of cuticular wax in Brassica napus. BMC Plant Biol 13, 215 (2013).

Wang, X. et al. Integration of Transcriptome and Metabolome Reveals Wax Serves a Key Role in Preventing Leaf Water Loss in Goji (Lycium barbarum). Int J Mol Sci, 25 (2024).

Kunst, L. & Samuels, L. Plant cuticles shine: advances in wax biosynthesis and export. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12, 721–7 (2009).

Bernard, A. & Joubès, J. Arabidopsis cuticular waxes: advances in synthesis, export and regulation. Prog Lipid Res 52, 110–29 (2013).

Borisjuk, N., Hrmova, M. & Lopato, S. Transcriptional regulation of cuticle biosynthesis. Biotechnol Adv 32, 526–40 (2014).

Lee, S. B. & Suh, M. C. Advances in the understanding of cuticular waxes in Arabidopsis thaliana and crop species. Plant Cell Rep 34, 557–72 (2015).

Bourdenx, B. et al. Overexpression of Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM1 promotes wax very-long-chain alkane biosynthesis and influences plant response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol 156, 29–45 (2011).

Rowland, O. et al. CER4 encodes an alcohol-forming fatty acyl-coenzyme A reductase involved in cuticular wax production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 142, 866–77 (2006).

Seo, P. J. et al. The MYB96 transcription factor regulates cuticular wax biosynthesis under drought conditions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23, 1138–52 (2011).

Lee, S. B., Kim, H. U. & Suh, M. C. MYB94 and MYB96 Additively Activate Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol 57, 2300–2311 (2016).

Xu, H. et al. The reference genome and full-length transcriptome of pakchoi provide insights into cuticle formation and heat adaption. Hortic Res 9, uhac123 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Cloning and expression analysis of waxy-related genes in Brassica napus. J Agric Biotechnol, 25 (2017).

Zhang, J. Y. et al. Overexpression of WXP1, a putative Medicago truncatula AP2 domain-containing transcription factor gene, increases cuticular wax accumulation and enhances drought tolerance in transgenic alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Plant J 42, 689–707 (2005).

Rowland, O. et al. The CER3 wax biosynthetic gene from Arabidopsis thaliana is allelic to WAX2/YRE/FLP1. FEBS Lett 581, 3538–44 (2007).

Mao, B. et al. Wax crystal-sparse leaf2, a rice homologue of WAX2/GL1, is involved in synthesis of leaf cuticular wax. Planta 235, 39–52 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. Expression and diversification analysis reveals transposable elements play important roles in the origin of Lycopersicon-specific lncRNAs in tomato. New Phytol 209, 1442–55 (2016).

Fahad, M., Tariq, L., Muhammad, S. & Wu, L. Underground communication: Long non-coding RNA signaling in the plant rhizosphere. Plant Commun 5, 100927 (2024).

Urquiaga, M. C. O., Thiebaut, F., Hemerly, A. S. & Ferreira, P. C. G. From Trash to Luxury: The Potential Role of Plant LncRNA in DNA Methylation During Abiotic Stress. Front Plant Sci 11, 603246 (2020).

Yang, W. et al. Epigenetic modifications: Allusive clues of lncRNA functions in plants. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 21, 1989–1994 (2023).

Chowdhury, M. R., Bahadur, R. P. & Basak, J. Genome-wide prediction of cauliflower miRNAs and lncRNAs and their roles in post-transcriptional gene regulation. Planta 254, 72 (2021).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 12, 357–60 (2015).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–30 (2014).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol 33, 290–5 (2015).

Pertea, G. & Pertea M. GFF Utilities: GffRead and GffCompare. F1000Res, 9 (2020).

Kang, Y. J. et al. CPC2: a fast and accurate coding potential calculator based on sequence intrinsic features. Nucleic Acids Res 45, W12–w16 (2017).

Sun, L. et al. Utilizing sequence intrinsic composition to classify protein-coding and long non-coding transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res 41, e166 (2013).

Wang, G. et al. Characterization and identification of long non-coding RNAs based on feature relationship. Bioinformatics 35, 2949–2956 (2019).

Min, X. J., Butler, G., Storms, R. & Tsang, A. OrfPredictor: predicting protein-coding regions in EST-derived sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 33, W677–80 (2005).

Mistry, J. et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D412–d419 (2021).

Consortium, UniProt. UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res 51, D523–d531 (2023).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP547019 (2024).

Du, K. et al. Transcriptome profiling of mRNA and lncRNA involved in wax biosynthesis in cauliflower. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27727356 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major Science and Technology Projects of the Yunnan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (202302AE09006) and Pre-research Foundation of Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2025KYZX-05). This study used computational resources from the National Supercomputing Center in Wuzhen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kanghua Du: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Yirong Li and Lingmin Wang: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Da Zhang, Jixian Ma, and Lingfeng Bao: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation. Zhengfu Tang: Investigation, Supervision. Jie Zhang, Wanfu Mu and Long Yang: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, K., Li, Y., Wang, L. et al. Transcriptome profiling of mRNA and lncRNA involved in wax biosynthesis in cauliflower. Sci Data 12, 1511 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05816-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05816-w