Abstract

Acropora corals, primary reef-builders providing habitat for numerous marine species, now face novel survival pressures due to environmental changes. Acropora intermedia (Brook 1891), a significant contributor to the vibrant ecosystems of coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific Ocean, also exhibits enhanced resistance to both thermal and acid stress. To advance future studies, we report an improved high-quality genome assembly for A. intermedia obtained through PacBio Hi-Fi long-read sequencing, with a total size of 496.8 Mb. Compared to the previous version, our genome assembly shows substantial improvements in contiguity, with the Contig N50 increasing from 40.3 Kb to 2.9 Mb, and the number of contigs decreasing from 20,998 to 633. Specifically, our genome exhibits no undetectable ambiguous bases (N’s) per 100 Kbp, which is remarkably lower than the previous version (5,276.11 per 100 Kbp). The percentage of assembly completeness evaluation based on Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) has increased from 90.6% to 92.6%. We predict a total of 26,852 protein-coding genes, with a BUSCO completeness of 95.7%, marking a 2.7% increase from the previous assembly. Our re-annotation and improved genome assembly of A. intermedia provide a valuable resource for further studies on coral adaptation mechanisms under climate change, and will facilitate comparative and evolutionary research of Acropora.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Coral, as one of the oldest inhabitants on Earth, plays a foundational role in the coral reef ecosystems they constitute1. Coral reef ecosystems are of immense ecological and economic importance, contributing to coastal protection, marine water purification, and the regulation of the carbon cycle. However, these ecosystems are exceptionally sensitive and vulnerable, responding acutely to environmental changes2,3,4,5,6. To date, nearly 50% of the coral reefs have been degraded worldwide, with 14% of that degradation occurring within the past decade4. Reef-building corals are ecologically significant due to their fundamental contributions to reef formation, ecosystem regulation, and biodiversity support7,8. Acropora, a genus of reef-building corals, is widely distributed across the globe, spanning vast oceanic regions from the Red Sea to the Indo-Pacific and even the Caribbean9,10. This genus is known for its great diversity and abundance, serving as the dominant genus of reef-building corals in the Indo-Pacific region11,12. Unfortunately, Acropora species have suffered from severe bleaching events13,14,15, leading to the loss of large areas of coral reefs. Given these challenges, understanding how Acropora responds to the environment is desired. This exploration may necessitate the application of omics-based approaches to uncover adaptive mechanisms that could inform conservation strategies.

Acropora digitifera was the first coral species to have its genome sequenced16, followed by the subsequent release of additional Acropora genomes17,18,19,20. To date, 26 genomes of Acropora coral are available on NCBI. These resources enable comparative analyses, functional gene studies, and adaptive trait investigations, offering molecular insights into stress resistance and diversification. Omics analyses have identified the genes related to symbiosis, may play pivotal roles in enabling Acropora corals to withstand environmental stressors19. Analysis of three hybrid corals (Acropora cf. gemmifera, Acropora cf. humilis, and Acropora cf. monticulosa) within the A. cf. humilis complex, integrating morphological and genomic data, revealed anomalous genomic regions under selection21. These regions include coding sequences potentially involved in thermotolerance or stress response. Consistent with this, hybridization likely facilitated the adaptive radiation of Acropora corals through genomic and mitochondrial data analysis22. Otherwise, In two high-quality, contiguous Acropora genomes, lineage-specific gene family expansion was identified, which may confer a survival advantage23. These advancements without exception highlight the significance of genomic data in the study of Acropora corals.

A. intermedia is particularly widespread and has demonstrated obvious heat resistance during the extensive coral bleaching event that occurred in China’s Greater Bay Area in 202024,25. Therefore, this species is an excellent model for studying coral bleaching and hybridization with congeneric species26. Investigating hybridization events among Acropora corals can provide valuable insights into reticulate evolution. The first A. intermedia genome assembled using short-read methodologies with the overall quality and annotation requiring improvement19. However, the genome assembled from Next-Generation Sequencing (Illumina HiSeq. 2500) reads may exhibit deficiencies in resolving complex repetitive regions, accurately detecting structural variations, performing synteny analyses, and studying gene families. Particularly for A. intermedia, research on thermal tolerance mechanisms and hybridization dynamics critically depends on high-quality genomic resources. To solve these problems and expand the genomic resources available for corals in the South China Sea and, particularly for Acropora, we reassembled and re-annotated a new version of the A. intermedia genome based on long-read PacBio HiFi sequencing, which spans 496.8 Mb with a Contig N50 of 2.9 Mb. BUSCO analysis indicated a completeness of 92.6% (C: 92.6%, S: 91.2%, D: 1.4%, F: 3.4%, M: 4.0%, n: 954). Our assembly exhibits a significant improvement in quality compared to the previous version (Contig N50: 40.3 Kb, BUSCO completeness: 90.6%). The completeness of gene models, assessed via BUSCO, has reached 95.7% (C: 95.7%, S: 93.7%, D: 2.0%, F: 1.9%, M: 2.4%, n: 954), reflecting a 2.7% increase. This enhanced A. intermedia genome offers greater contiguity and completeness, improving data quality and enabling important analysis like structural variations, evolutionary dynamics, and horizontal gene transfer.

Methods

Sample collection and DNA extraction

The samples of A. intermedia were obtained by scuba diving from the Fenghuang Island (Sanya, Hainan Province, China; 18°14′24.70″ N, 109°29′38.31″ E) in June 2024 (Fig. 1). Fresh partial adult A. intermedia sample was cut into small pieces and washed using 3 x PBS. The coral tissue was digested utilizing Type II collagenase (2 mg/ml), and the mixed symbiotic algae and coral polyp cells were separated by performing multiple rounds of brief centrifugation. During this process, most of the algae settled at the bottom of the centrifuge tube, while the supernatant retained pure polyp cells. The supernatant was carefully aspirated, centrifuged, and the resulting pellet was collected as the material for subsequent DNA extraction. DNA was extracted using the phenol-chloroform extraction27. The Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer was utilized to measure the quantity of genomic DNA, ensuring that the OD260/280 ratio was between 1.8 and 2.0, and the OD260/230 ratio was between 2.0 to 2.2. Additionally, the purity and structural integrity of the DNA were evaluated through 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Library preparation and sequencing

A total of 30 µg of DNA was used for the construction of a Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) library for PacBio sequencing in Novogene (Beijing, China). The HiFi sequencing library was prepared according to standard PacBio protocols using the SMRTbell™ Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, California, USA). Sequencing was performed on the PacBio Sequel II systems (Pacific Biosciences, California, USA). The raw data was transmitted from the sequencer to SMRTLink v13.1 (https://www.pacb.com/support/software-downloads/), where the CCS algorithm was employed to generate HiFi reads.

Genome size estimation

Prior to assembly, the genome size of A. intermedia was estimated using k-mer analysis of raw PacBio HiFi reads. The raw reads were quality-trimmed using fastplong v.0.3828 (-m 20 -l 100 -w 12) and fragmented into 150 bp via custom simple python script. Subsequently, the fragmented reads were used to generate a histogram based on k-mer = 21 with Jellyfish v2.329 (-C -m 21 -h 1,000,000). The output histogram from Jellyfish was subsequently visualized using the online server GenomeScope v.1 (http://genomescope.org)30 with parameter k = 21, ploidy = 2, Read length = 150, and maximum k-mer coverage = 1,000,000 (Fig. 2).

Genome assembly and genome quality assessment

Based on previous studies demonstrating superior performance in terms of Con-tig N50 and BUSCO completeness scores for similar datasets, Hifiasm was chosen for initial assembly with default parameters31,32,33. Haploid duplications were removed using Hifiasm’s integrated functionality. To enhance consensus sequence accuracy, three rounds of polishing were performed using Racon v1.5.034. The genome completeness was assessed with BUSCO v5.2.235, employing the conserved metazoan gene set known as “metazoa_odb10”. Additionally, we used the snailplot-assembly-stats to create a SnailPlot (https://github.com/hanwnetao/snailplot-assembly-stats) to visualize our assembly statistics (Fig. 3).

Genome assembly overview of A. Intermedia. The contiguity and completeness of the A. intermedia genome assembly, post-contamination screening, is represented by a circle plot reflecting the full assembly length (~496.8 Mb), distributed across 633 contigs. The Contig N50 (2.9 Mb) is marked in dark orange, and the N90 (536.7 Kb) in light orange. The longest contig was 11.8 Mb (highlighted in red). The BUSCO scores are shown in the top right corner in green.

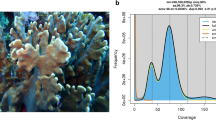

To assess potential contamination, the assembly was screened for non-target DNA using Blobtools v1.1.136. Taxonomic classification was performed by aligning the top hit from BLAST v2.9.037 against the NCBI NT database, with an e-value threshold of 1e-5 (Fig. 4).

Quality assessment and contamination detection of the A. intermedia genome assembly. (a) Histograms above depict the distribution of coverage. BlobPlot showing taxonomic affiliation at the phylum rank level for A. intermedia. (b) The average GC content. Blue dots show contigs with best BLAST hits to Cnidaria.

The newly generated genome assembly statistics were compared with the previous genome version (GCA_014634585.1) using QUAST v5.2.038. A comparison of the two versions of the genome information is summarized in Table 1.

Repeat annotation

Prior to masking repetitive elements, a de novo library of repeats was constructed for the final A. intermedia genome assembly using RepeatModeler v.2.0.139. RepeatMasker v4.1.740 was then used to predict repeat sequence with the de novo self-training result generated by RepeatModeler serving as the input targeting the RepBase-20181026 database. RepeatMasker masked 47.91% of the genome, with most of the repeats being unclassified (20.37%). Transposable elements (TEs) were predicted using EDTA v2.2.241 for de novo prediction. The TE library of EDTA was obtained after filtering. Combined with the results of RepeatMasker and EDTA, the final genome repeat sequence annotation was compiled (Table 2).

Gene prediction and annotation

We employed multiple methods for genome structure annotation. First, we used the Augustus v3.342 for de novo gene prediction. Genomes of all species in the genus Acropora were downloaded from NCBI to create the test and training sets for the model. After training, the model was used to predict genes on A. intermedia. Additionally, the transcriptome data of A. intermedia (SRP226139) was obtained from NCBI, and transcript assembly was performed using Trinity v2.15.143. We further mapped and aligned the assembled transcripts back to the genome using the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments (PASA) v2.5.244. Finally, the results from these strategies were integrated into a unified gene annotation using the EVidenceModeler v1.1.145.

For non-coding RNA annotations, we download Rfam databases46,47,48 and annotated ncRNAs, snRNA, and microRNA using infernal v1.1.449 based on the Rfam database. The rRNA annotation was performed using RNAMMER v1.250. In addition, 12,556 high-confidence transfer RNAs were predicted using tRNAscan-SE v2.0.1251 based on filtering of the initial set of 15,871 putative tRNAs using EukHighConfdenceFilter. The final statistical results are summarized in Table 3.

The functional annotation of the predicted protein-coding genes was performed by aligning protein sequences against the eggNOG 5.052 using DIAMOND v2.1.852, followed by hmmsearch (HMMER v3.3.2)53,54 validation against Pfam HMMs for conserved domain identification. In both the DIAMOND v2.1.8 alignment against the eggNOG database and the hmmsearch against Pfam HMMs, results with E-values greater than 1e-5 were removed to ensure the accuracy of the annotations. Additionally, protein function predictions were performed using various databases to revalidate the accuracy and enhance the completeness of the annotations, including Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)55 and Gene Ontology (GO)56. These databases were employed in conjunction with InterProScan v5.3657 to predict protein functions by analyzing the conserved protein domains. Specifically, BLASTP v2.2.2 was used against the SwissProt database 2025_0158, and DIAMOND v2.1.8 was applied against the NR database. Finally, all functional annotation files were merged using a Python script. In summary, 26,611 (99.1%) genes were successfully annotated (Table 4).

Data Records

The raw sequencing data and genome assembly of Acropora intermedia are available at: https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP566323 (PacBio Hifi data)59, and https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_048544155.1 (genome assembly)60. Additionally, the predicted protein (.gff) and CDS files are available in the figshare database61.

Technical Validation

Through third-generation PacBio sequencing, 14.2 Gb of raw reads were generated. Before genome assembly, k-mer analysis predicted the genome size to be 433.11 Mb with a heterozygosity rate of 1.95% (Fig. 2). The final assembly consists of 633 contigs, totaling 496.8 Mb, with a Contig N50 of 2.9 Mb, L50 of 46, and a maximum contig length of 11.8 Mb (Fig. 3). Upon completion of the genome assembly, we assessed its contiguity, accuracy, and completeness using multiple approaches. The BUSCO completeness of the genome was 92.6% (C: 92.6%, S: 91.2%, D: 1.4%, F: 3.4%, M: 4.0%, n: 954), including both complete and fragmented genes (Fig. 3). Quality assessment and contamination detection of the A. intermedia genome show that 99.76% of contigs have been aligned to the NCBI nt database and belong to the phylum Cnidaria. 95.85% of PacBio HiFi reads were mapped to the genome (Fig. 4). The unmapped rate of 4.15% refers to the proportion of PacBio HiFi reads that did not align with the genome. These reads might have been discarded as contamination during assembly or belong to organellar (e.g. Mitochondria). A comparative analysis with the previous genome version, based on statistical metrics (Table 1), demonstrated significant improvements. Notable enhancements include a substantial increase in Contig N50 from 40.3 Kb to 2.9 Mb, a reduction in the total number of contigs from 20,998 to 633, and the elimination of N’s from 5,276.11 per 100 Kbp to 0. These findings indicate a marked improvement in the contiguity of the genome assembly, with the Contig N50 being over 73 times larger than the previous version. BUSCO analysis of the 633 contigs revealed that 954 (92.6%) of the metazoan single-copy orthologs were fully represented, with 91.2% of these in the single-copy orthologs and 1.4% duplicated. A small fraction, 3.4%, of orthologs were fragmented, and 7.4% were missing. Through structural annotation, 792,517 repeat elements were identified genome-wide. Among the classified repeats, long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons represent the most abundant category (Table 2). Additionally, 17,829 RNA-associated elements and 26,852 protein-coding genes were annotated in the A. intermedia genome (Tables 3 and 4). Furthermore, evaluation of the gene models through BUSCO indicated a gene model completeness of 95.7%, with only 43 genes (4.3% of the total) missing in the final annotated genome (Table 1). These results collectively highlight the high quality, continuity, and completeness of the genome assembly. The update genome of A. intermedia provides an essential resource for deciphering its adaptive thermotolerance and hybrid compatibility, with implications for reef restoration strategies and reconstruction of scleractinian evolutionary history.

Code availability

All bioinformatics software utilized in this research was operated in accordance with the manuals and protocols furnished by their respective developers, with detailed records of specific versions and parameters outlined in the Methods section. In instances where parameters were unspecified, the default configurations were utilized. No custom code was used for the analysis.

References

Shinzato, C. & Yoshioka, Y. Genomic Data Reveal Diverse Biological Characteristics of Scleractinian Corals and Promote Effective Coral Reef Conservation. Genome Biol Evol 16, evae014, https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evae014 (2024).

Lachs, L. et al. Natural selection could determine whether Acropora corals persist under expected climate change. Science 386, 1289–1294, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adl6480 (2024).

Voolstra, C. R., Peixoto, R. S. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Mitigating the ecological collapse of coral reef ecosystems: Efective strategies to preserve coral reef ecosystems. EMBO. Rep. 24, e56826, https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202356826 (2023).

Obura, D. et al. Vulnerability to collapse of coral reef ecosystems in the Western Indian Ocean. Nat. Sustain 5, 104–113, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00817-0 (2022).

Perry, C. et al. Implications of reef ecosystem change for the stability and maintenance of coral reef islands. Global Change Biol 17, 3679–3696, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02523.x (2011).

Graham, N. A. et al. Dynamic fragility of oceanic coral reef ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA 103, 8425–8429, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0600693103 (2006).

Brandl, S. J. et al. Demographic dynamics of the smallest marine vertebrates fuel coral reef ecosystem functioning. Science 364, 1189–1192, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav3384 (2019).

Komyakova, V., Jones, G. P. & Munday, P. L. Strong effects of coral species on the diversity and structure of reef fish communities: A multi-scale analysis. PloS one 13, e0202206, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202206 (2018).

Huntington, B. E., Miller, M. W., Pausch, R. & Richter, L. Facilitation in Caribbean coral reefs: high densities of staghorn coral foster greater coral condition and reef fish composition. Oecologia 184, 247–257, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-017-3859-7 (2017).

Ball, E.E., Hayward, D.C., Bridge, T.C. & Miller, D.J. Acropora—The Most-Studied Coral Genus. Handbook of Marine Model Organisms in Experimental Biology 173–193, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003217503-10 (2021).

Cairns, S. D. Species richness of recent Scleractinia. Atoll res. bull 459, 1–46, https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00775630.459.1 (1999).

Richards, Z. T., Syms, C., Wallace, C., Muir, P. & Willis, B. Multiple types of rarity in the coral genus Acropora. Div. Dist. 1, 12 (2013).

Adam, A. A. et al. Diminishing potential for tropical reefs to function as coral diversity strongholds under climate change conditions. Div. Dist. 27, 2245–2261, https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13400 (2021).

Meenatchi, R. et al. Revealing the impact of global mass bleaching on coral microbiome through 16S rRNA gene-based metagenomic analysis. Microbiol. Res. 233, 126408, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2019.126408 (2020).

Fuller, Z. L. et al. Population genetics of the coral Acropora millepora: Toward genomic prediction of bleaching. Science 369, eaba4674, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba4674 (2020).

Shinzato, C. et al. Using the Acropora digitifera genome to understand coral responses to environmental change. Nature 476, 320–323, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10249 (2011).

Shumaker, A. et al. Genome analysis of the rice coral Montipora capitata. Sci. Rep. 9, 2571, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39274-3 (2019).

Helmkampf, M., Bellinger, M. R., Geib, S. M., Sim, S. B. & Takabayashi, M. Draft genome of the rice coral Montipora capitata obtained from linked-read sequencing. Genome Biol Evol 11, 2045–2054, https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evz135 (2019).

Shinzato, C. et al. Eighteen coral genomes reveal the evolutionary origin of Acropora strategies to accommodate environmental changes. Mol Biol Evol 38, 16–30, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa216 (2021).

Ying, H. et al. Comparative genomics reveals the distinct evolutionary trajectories of the robust and complex coral lineages. Genome Biol. 19, 175, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-018-1552-8 (2018).

Furukawa, M. et al Introgression and adaptive potential following heavy bleaching events in Acropora corals. Current biology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2025.05.038 (2025).

Wu, T., Xu, A. N., Lei, Y. & Song, H. Ancient hybridisation fuelled diversification in Acropora Corals. Mol. Ecol. e17615, https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.17615 (2024).

Takeuchi, T. et al. Nearly T2T, phased genome assemblies of corals reveal haplotype diversity and the evolutionary process of gene expansion. DNA research. dsaf017, Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1093/dnares/dsaf017 (2025).

Sun, Y. et al. Impact of Ocean Warming and Acidification on Symbiosis Establishment and Gene Expression Profiles in Recruits of Reef Coral Acropora intermedia. Front. Microbiol. 11, 532447, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.532447 (2020).

Zhao, Y., Chen, M., Chung, T. H., Chan, L. L. & Qiu, J.-W. The 2022 summer marine heatwaves and coral bleaching in China’s Greater Bay Area. Mar. Environ. Res. 189, 106044, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2023.106044 (2023).

Isomura, N., Iwao, K. & Fukami, H. Possible natural hybridization of two morphologically distinct species of Acropora (Cnidaria, Scleractinia) in the Pacific: fertilization and larval survival rates. PloS One 8, e56701, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056701 (2013).

Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. R. & Maniatis, T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual 2nd edn, https://doi.org/10.1016/0307-4412(83)90068-7 (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1989).

Chen, S. Ultrafast one-pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using fastp. iMeta 2, e107, https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.107 (2023).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 (2011).

Vurture, G. W. et al. GenomeScope: fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics 33, 2202–2204, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btx153 (2017).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021).

Cheng, H. et al. Haplotype-resolved assembly of diploid genomes without parental data. Nat. Biotechnol 40, 1332–1335, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01261-x (2022).

Cheng, H., Asri, M., Lucas, J., Koren, S. & Li, H. Scalable telomere-to-telomere assembly for diploid and polyploid genomes with double graph. Nat. Methods 21, 967–970, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02269-8 (2024).

Vaser, R., Sović, I., Nagarajan, N. & Šikić, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome. Res. 27, 737–746, http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.214270.116 (2017).

Seppey, M., Manni, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: Assessing Genome Assembly and Annotation Completeness. Methods. Mol. Biol. 1962, 227–245, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_14 (2019).

Laetsch, D. R. & Blaxter, M. L. BlobTools: Interrogation of genome assemblies [version 1; peer review: 2 approved with reservations]. F1000Research 6, 1287, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.12232.1 (2017).

McGinnis, S. & Madden, T. L. BLAST: at the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 32, W20–W25, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh435 (2004).

Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N. & Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 29, 1072–1075, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 (2013).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinform. 25, 4–10, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2009).

Ou, S. et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol 20, 275, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1905-y (2019).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res 34, W435–W439, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl200 (2006).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Trinity: reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nat. Biotechnol 29, 644, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1883 (2011).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res 31, 5654–5666, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkg770 (2003).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol 9, R7, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7 (2008).

Ontiveros-Palacios, N. et al. Rfam 15: RNA families database in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res 53, D258–D267, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae1023 (2025).

Kalvari, I. et al. Rfam 14: expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microRNA families. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D192–D200, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa1047 (2021).

Kalvari, I. et al. Non-Coding RNA Analysis Using the Rfam Database. Current protocols in bioinformatics 62, e51, https://doi.org/10.1002/cpbi.51 (2018).

Nawrocki, E. P., Kolbe, D. L. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.0: inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics 25, 1335–1337, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp157 (2009).

Lagesen, K. et al. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 35, 3100–3108, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm160 (2007).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 25, 955–964, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.5.955 (1997).

Cantalapiedra, C. P., Hernández-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P. & Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol Biol Evol 38, 5825–5829, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab293 (2021).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3176 (2015).

Eddy, S. R. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002195, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002195 (2011).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Tanabe, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res 45, D353–D361, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw1092 (2017).

The Gene Ontology Consortium. et al. The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 224, iyad031, https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyad031 (2023).

Blum, M. et al. The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D344–D354, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa977 (2021).

Bairoch, A. & Apweiler, R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence data bank and its supplement TrEMBL in 1999. Nucleic Acids Res 27, 49–54, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.1.49 (1999).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP566323 (2025).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_048544155.1 (2025).

Han, W. & Chang, X. Acropora intermedia genome. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28532630.v1 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Mr. Yaxing Liu (Sanya Coral Reef Ecology Institute, Hainan Province, China) for her contribution made in species identification. We also extend our thanks to Mr. Yi-Tao Lin (Hong Kong Baptist University) for his insightful revisions of the manuscript. Additionally, we wish to acknowledge the support provided by the High-Performance Biological Supercomputing Center at the Ocean University of China for this research. This research was funded by Guangdong Provincial Key Areas R&D Program Project (2025B1111180001), Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (SOLZSKY2025013), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32222085), Outstanding Talent Team Project of Hainan Province (HNYT20240001), Innovational Fund for Scientific and Technological Personnel of Hainan Province (KJRC2023A02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.B., S.W. and H.C. conceived and designed the study. Z.B., S.W. and H.C. coordinated and supervised the whole study. XY.C and W.H. conducted the genome assembly and analysis. XY.C and C.T. extracted DNA. H.H. and H.C. were responsible for coral sample collection and photography in this study. K.C., D.W., L.L. and J.H. participated in discussions and provided suggestions for manuscript improvement. XY.C, W.H. and XM.C did most of the writing with input from other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, X., Han, W., Chen, X. et al. Re-annotation improved large-scale assembly of the reef-building coral Acropora intermedia. Sci Data 12, 1504 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05849-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05849-1