Abstract

Mangrove and forested wetland ecosystems represent critical carbon reservoirs, yet uncertainties in belowground carbon stock estimates hinder their inclusion in climate mitigation strategies. Here we present soil carbon stock density data for mangrove and forested wetland ecosystems across Panama’s Pacific and Caribbean regions. We established 45 permanent plots across marine and riparian mangrove typologies and 14 permanent plots in forested wetlands, collecting 544 soil cores to quantify soil carbon stocks. Soil samples were analyzed for bulk density, organic matter content, and organic carbon concentration, enabling calculation of carbon stock density at 0.3 m and 0.5 m depth profiles. Soil carbon stock density estimates differed among marine mangroves, riparian mangroves, and forested wetlands, reflecting ecosystem heterogeneity including mineral versus peat soils. These data provide essential ground-truth measurements contributing to Panama’s national carbon accounting and climate commitments for the Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry sector. The standardized methodology facilitates integration with regional carbon monitoring efforts across Central America and the Caribbean, supporting blue carbon database development and carbon mapping validation initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The conservation, restoration, and sustainable management of ecosystems represent important approaches for addressing global warming1. Consequently, these actions, known as Nature-based Solutions (NbS), have become major components of climate strategies worldwide1,2,3. Ecosystems with substantial belowground carbon stocks are particularly important because belowground carbon stocks exceed aboveground carbon stocks globally. For example, peatlands hold 644 Gigatons of carbon (GtC) belowground4, equivalent to approximately twice the carbon stock allocated in the living biomass of the world’s forests4,5.

Mangroves contain substantial above- and belowground carbon stocks in tropical regions6, covering 14.7 Mha7 and holding between 5.2 and 8.6 GtC8. Among mangroves, those growing on peat have the largest carbon stocks6. These ecosystems play central roles in conserving biodiversity in the tropics while simultaneously protecting coastlines9. Despite their importance as carbon reservoirs and biodiversity habitats, mangroves face threats from land use change (e.g., urban, agriculture, aquaculture) and climate change (e.g., severe droughts, sea level rise) worldwide10. Forested wetlands, without including mangroves, also represent major carbon sinks in the tropics as they cover 58.7 Mha and hold 119.2 GtC4,11. These ecosystems, like mangroves, are subjected to various threats that compromise their carbon stocks and sink capacity (e.g., drainage for agriculture and afforestation, land use change for road construction, urban development, and mining)12.

In Panama, the Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) sector is the main net carbon sink supporting the country’s climate commitments13. Consequently, Panama has elevated the role of forests, including mangroves and peatlands, in its Nationally Determined Contributions14. Mangroves in Panama cover approximately 0.187 Mha of the national territory15; however, their carbon stock remains uncertain, ranging between 25 and 71 MtC15,16,17,18. The extent and carbon stock of forested wetlands, particularly forested peatlands, remains unknown, contributing to uncertainty in national carbon stock estimates and hindering the inclusion of quantitative conservation and restoration pledges in Panama’s climate strategy14. This uncertainty derives mainly from: i) limited ground data (above- and belowground) and ii) different methodological approaches for calculating carbon stock densities (tC ha−1). For example, specific sampling methodology (e.g., site selection, plot design, and stratification) defines the representativeness of data collection. Furthermore, as the main carbon pool in these ecosystems lies belowground, the selection of the protocols for sampling and estimating belowground carbon stocks (e.g., using percentage of loss on ignition versus percentage of carbon content) contributes significantly to increased uncertainty in carbon reservoir estimates at the landscape level, hampering comparison of results across different studies. However, access to raw ground data enables assessment, recalculation, and comparison of national and regional databases and their carbon stock estimates. This is particularly important for belowground carbon pool components, as existing data are limited due to the logistical and financial challenges involved in sample collection, preparation, and analysis19.

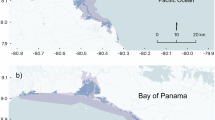

This manuscript presents raw data for estimating belowground soil carbon stock density in mangrove and forested wetland ecosystems from Panama’s Pacific and Caribbean regions. The dataset includes information, collected following standard guidelines20,21,22, from 45 permanent plots across marine and riparian mangrove typologies and 14 permanent plots in forested wetlands (Fig. 1). In addition, we have included existing published data to improve the spatial representativeness of the dataset and to contrast and contextualize our estimates; specifically, data from 21 mangrove plots23 and 1 forested peatland plot24 (Dataset: n = 81 plots) (Fig. 1). This information can serve as the basis for developing a regional soil carbon database based on the ongoing national mangrove inventories across Central America and the Caribbean (e.g., the Regional Blue Carbon Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification Mechanism (MRV) funded by the UK-Blue Carbon Fund in Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Suriname, Colombia, and Panama). Furthermore, the information included in this manuscript will support ground validation efforts focused on mapping national and regional peatlands19,25. For Panama, the information included in this data descriptor will directly contribute to harmonizing existing soil data for mangrove ecosystems and fulfilling its peatland NDC commitments: i) creating the first national peatland distribution map and ii) assessing carbon stocks in peatlands and forested wetlands14.

Methods

The primary data included in this manuscript were collected during the execution of: i) the “Valuing, Protecting and Enhancing Coastal Natural Capital in Panama (PN-T1233)/Blue Natural Heritage” project, executed by Audubon Americas and funded by the UK Blue Carbon Fund through the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) via the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and ii) the PFID-FID-2021-114 Project “Hidrología, Reservas de Carbono, Plantas y Peces de Matusagaratí” funded by SENACYT. Fieldwork and laboratory analyses were conducted between 2010 and 2024, following standardized protocols for mangrove and peatland ecosystems, including plot allocation and design, as well as sample collection, processing, and analysis20,21,22. Detailed field and laboratory protocols adhered to established carbon stock estimation guidelines for mangrove and peatland ecosystems19,21,26,27,28. Data from literature sources were selected based on their use of standardized protocols equivalent to those used for both sampling and sample analyses for the primary data.

Plot design

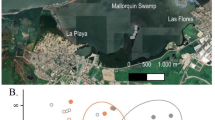

For the PN-T1233 project, we established 45 mangrove plots (24 marine and 21 riparian)29. Each plot comprised a linear transect with six circular subplots arranged perpendicular to the sea or river shore. Each subplot had a 7 m radius and was separated by a 25 m distance between the center of each subplot (Fig. 2a)20,22. Within each subplot, we established a nested 2 m radius subplot. The published data for mangroves included in this data descriptor were also developed using standardized protocols20,21 and followed an equivalent plot and sampling design to those we used to generate the primary data23.

For forested wetlands, we established 14 plots (20 × 50 m)30. We collected soil cores at the center of the plot and, when possible, given the logistical capabilities, in two opposite corners of each plot (Fig. 2b).

Soil collection

We collected 544 soil cores using a Russian peat borer (04.09, Eijkelkamp, Netherlands) for physicochemical characterization and belowground carbon stock density estimation. The borer extracted semi-cylindrical soil samples (0.5 m length, 52 mm diameter) in 0.5 m increments. For both mangroves and forested wetlands, we took samples in areas where roots > 5 cm diameter did not interfere with the borer operation, until mineral soil was reached (Fig. 2). To improve bulk density estimates, where coarse roots (0.2–5 cm diameter) interfered with soil collection in the upper 0.2 m, we collected one additional surface sample (0.1 × 0.1 × 0.1 m) adjacent to each core site. We wrapped all samples in cling film to minimize water loss and stored them in dark conditions at 2 °C to prevent photo- and biodegradation until analysis at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute’s Analytical Biogeochemistry Laboratory.

Soil characterization

We characterized the 50 cm soil cores using two approaches: i) 0.1 m resolution (i.e, 0 to 10, 10 to 20, 20 to 30, 30 to 40, and 40 to 50 cm segments) or ii) 0 to 15, 15 to 30, and 30 to 50 cm segments. For each segment, we measured bulk density, loss on ignition (LOI), pH, total carbon (0–0.1, 0.2–0.3, and 0.4–0.5 m depth segments), and soil texture on selected samples (Fig. 2).

Bulk density was determined gravimetrically from water mass loss (70 °C, 72 h) using 5 cm semicylindrical core sections27. LOI serves as a proxy for soil organic matter (SOM) and was determined by measuring mass loss at 550 °C for 1 hour. LOI values increase with soil organic matter content. We measured pHw in 1:2 soil fresh weight-deionized water solution. Total organic carbon (Corg) was analyzed from homogenized, < 2 mm sieved, soil samples (0.5 g) using a total elemental analyzer (Thermo Flash EA 1112; CE Instruments, Wigan, UK). Before measuring total organic carbon, we tested samples for inorganic carbon presence using 1 N HCl20,21. If carbonates were present, we measured total organic carbon on samples pre-treated with HCl to remove inorganic carbon-carbonates. We analyzed soil texture in triplicate using H2O2 pre-digested samples on a Horiba LA-960 Laser scattering particle size distribution analyzer, following USDA classifications. We defined peat as a ≥30 cm layer containing ≥30% dry weight organic matter31.

Belowground soil carbon stock density

We measured total organic carbon content (% Corg) in subsamples of the 10 cm segments. Specifically, in the 0–10, 20–30, and 40–50 cm segments in each core profile (total segments analyzed: 1,587). For sections where carbon content was not measured, we estimated % Corg by developing linear regression models for % Corg vs LOI. We developed models for marine mangroves (% Corg = 0.38 × % LOI − 1.41; R2 = 0.65, p < 0.0001, RMSE = 1.13) (Fig. 3a), riparian mangroves (% Corg = 0.36 × % LOI − 1; R2 = 0.6, p < 0.0001, RMSE = 1.27) (Fig. 3a), and forested wetlands (% Corg = 0.54 × % LOI − 3.4; R2 = 0.86, p < 0.0001, RMSE = 7.36) (Fig. 3b). We calculated belowground soil carbon stock density (BGCdS, tC ha−1) by multiplying the bulk density of each section by the volume of each layer and by its carbon content (i.e., Corg from linear regression model) and summing the carbon content in adjacent layers through the 0.5 m stratigraphic profiles32 (Fig. 2). We calculated BGCdS for 0.3 and 0.5 m soil depth profiles. The 0.3 m soil depth profile complies with Panama’s REDD+ guidelines33, while the 0.5 m soil depth provides additional information on site characteristics (e.g., peat validation).

Total organic carbon (%) versus loss on ignition (%) in (a) marine (blue) and riparian (purple) mangroves and (b) forested wetlands (green). Linear regression models are shown as black lines. The size of each marker corresponds to the relative value of its apparent dry bulk density; larger markers correspond to higher apparent dry bulk density.

Data Records

The datasets are available at the Figshare repository34: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28587746.

The data records comprise: i) raw data for calculating subplot- and plot-level mangrove and forested wetlands belowground soil carbon stock density, ii) belowground soil carbon stock density estimates for the 392 subplots, and iii) belowground soil carbon stock density estimates for the 81 plots (Fig. 4, Table 1).

Subplot-level belowground soil carbon stock density (BGCdS) for marine (blue) and riparian (purple) mangroves and forested wetlands (green) at: (a) 0.3 and (b) 0.5 m soil depth profiles. Mean BGCdS values are presented as yellow circles. Kruskal–Wallis test results: (a) 0.3 m depth stratigraphic profiles – Ecosystem|Typology (χ²₂ = 171.62, p < 0.0001), and (b) 0.5 m depth stratigraphic profiles – Ecosystem|Typology: (χ²₂ = 186.74, p < 0.0001).

Specifically, the datasets include:

-

(i)

Raw data file: CSV (comma separated values) file including the raw data for calculating subplot- and plot-level belowground soil carbon stock density with columns representing: Data source = This data descriptor or literature data23,24; Coast = Pacific or Caribbean; Ecosystem = Mangrove or Forested wetland; Study area = overall study area; Sub-study area = specific study area within Panama; Province = province within Panama; Latitude; Longitude; Typology = Marine and Riparian mangroves or Domed peatland; Plot = each of the 81 plots; Subplot = up to 6 on each plot; plotId = Plot + Subplot; Soil core # in plot or subplot = Core 1 (C1), Core 2 (C2) or Core 3 (C3) collected in each plot or subplot; Soil depth section range (m) = the segment length within the stratigraphic profile from surface (0 m) to bottom (0.5 m); Water content (%) = water amount per dry soil amount expressed as percentage; Bulk density (gsampled.b. cm−3) = amount of dry soil per cm−3 (i.e., apparent dry bulk density); LOI (%) = loss on ignition presented as percentage; pHw = hydrogen potential measured in a soil:water solution; Total Corg (%) = carbon content in dry soil presented as percentage; Total Corg (%, LOI Regression model) = carbon content estimated from the linear regression model % Corg vs % LOI; Sand (%) = soil texture analysis, percentage of sand in dry soil; Silt (%) = soil texture analysis, percentage of silt in dry soil; Clay (%) = soil texture analysis, percentage of clay in dry soil; Soil texture class = soil classification following USDA guidelines.

-

(ii)

Subplot-level estimates file: CSV file containing subplot-level belowground soil carbon density estimates with columns representing: Data source = This data descriptor or literature data23,24; Soil core identifier = unique sequential identifier assigned to each core (1 to 658); Coast = Pacific or Caribbean; Ecosystem = Mangrove or Forested wetland; Study area = overall study area; Sub-study area = specific study area within Panama; Province = province within Panama; Latitude; Longitude; Typology = Marine and Riparian mangroves or Domed peatland; Plot = each of the 81 plots; Subplot = up to 6 per plot; plotId = Plot + Subplot; Soil core # in plot or subplot = Core 1 (C1), Core 2 (C2) or Core 3 (C3) collected in each plot or subplot; belowground soil carbon density considering a 0.3 m depth profile (BGCdS 0.3 m depth, tC ha−1); belowground soil carbon density considering a 0.5 m depth profile (BGCdS 0.5 m depth, tC ha−1); Peat presence: Yes (Y) or No (N) according to the criteria defined in the Methods section; Max peat depth (m) = maximum peat depth per core.

-

(iii)

Plot-level estimates file: CSV file containing plot-level belowground soil carbon density estimates with columns representing: Data source = This data descriptor or literature data23,24; Coast = Pacific or Caribbean; Ecosystem = Mangrove or Forested wetland; Study area = overall study area; Sub-study area = specific study area within Panama; Province = province within Panama; Latitude; Longitude; Typology = Marine and Riparian mangroves or Domed peatland; Plot = each of the 81 plots; average plot-level belowground soil carbon density considering a 0.3 m depth profile (BGCdS 0.3 m depth, tC ha−1); standard error of the mean for plot-level belowground soil carbon density considering a 0.3 m depth profile (SE BGCdS 0.3 m depth (tC ha−1)); plot-level belowground soil carbon density considering a 0.5 m depth profile (BGCdS 0.5 m depth, tC ha−1); standard error of the mean for plot-level belowground soil carbon density considering a 0.5 m depth profile (SE BGCdS 0.5 m depth (tC ha−1)); Peat presence: Yes (Y) or No (N) according to the criteria defined in the Methods section; Max peat depth (m) = maximum peat depth per plot.

Technical Validation

Technical validation focused on evaluating the linear regression models relating % Corg to % LOI (Fig. 3). To assess model robustness and predictive performance, we conducted comprehensive cross-validation analyses using K-fold cross-validation (5 folds). Cross-validation results demonstrate consistent model performance across all validation methods. For marine mangroves, the models achieved mean R2 values of 0.65 ± 0.019, RMSE values of 1.14 ± 0.003 (hold-out), and MSE values of 1.29 ± 0.007. For riparian mangroves, the models achieved mean R2 values of 0.59 ± 0.01, RMSE values of 1.29 ± 0.001 (hold-out), and MSE values of 1.68 ± 0.004. Forested wetland models demonstrated the strongest predictive performance with R2 values of 0.86 ± 0.019, though with higher RMSE values, 7.446 ± 0.050, and MSE values of 55.44 ± 0.748 due to the broader range of carbon content values in peat environments. The cross-validation analyses confirm model stability, with standard deviations typically below 10% of mean values. Residual analysis revealed no systematic patterns, supporting the appropriateness of linear regression for these ecosystem-specific relationships. The strong predictive capability of the forested wetland model is likely due to the more homogeneous organic matter composition in peat environments compared to the mineral-organic soil matrices characteristic of mangrove ecosystems.

The linear regression models are consistent with data published for mangrove ecosystems from Micronesia26,35. Access to raw data (e.g., % Corg, % LOI, pHw) enables development of multivariable models for predicting % Corg. In addition, the raw data allow, if necessary, correcting estimates by structural water content in clay-rich samples36,37.

For mangrove ecosystems, our BGCdS estimates align with Global Mangrove Watch values for Panama (458 tC ha−1 at 1 m soil depth)38 and global average BGCdS values (350 tC ha−1 at 1 m soil depth)39. It is important considering that the estimation of BGCdS is subject to diverse potential sources of error as its calculation requires combining different parameters (e.g., apparent dry bulk density, LOI, soil total organic carbon). For example, the selection of equipment for soil core collection could represent a potential source of error as bulk density estimates can be significantly increased by vertical compression of soil samples. For this reason, we selected a Russian peat borer and, when necessary, collected additional soil samples (See Methods section). Omitting the removal of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) for determining total organic carbon in soils and sediments represents another potential source of error as it can lead to overestimation of carbon content21. This is particularly relevant when collecting soil samples from mangroves located in karstic regions and mangroves and peatlands associated with or adjacent to coral reefs, such as those in the Caribbean region.

Usage Notes

We calculated % Corg values for subplot- and plot-level soil carbon density estimates using linear regression models described in the Methods section: marine mangroves (% Corg = 0.38 × % LOI − 1.41; R2 = 0.65, p < 0.0001, RMSE = 1.13) (Fig. 3a), riparian mangroves (% Corg = 0.36 × % LOI − 1; R2 = 0.6, p < 0.0001, RMSE = 1.27) (Fig. 3a), and forested wetlands (% Corg = 0.54 × % LOI − 3.4; R2 = 0.86, p < 0.0001, RMSE = 7.36) (Fig. 3b). The mangrove models are adequate for mangroves growing on mineral soil rich in clay and silt but inadequate for mangroves growing on peat, such as those reported in the Caribbean and Southeast Asia6,24,40. The forested wetland models are adequate for forested peatlands.

Similar BGCdS values between mangroves and forested wetlands suggest that peat’s higher carbon content but lower bulk density compensates for mangroves’ lower carbon content but higher bulk density (Fig. 3, Table 1). Therefore, similar BGCdS values are observed when comparing stratigraphic profiles of the same depth. However, it is important to consider that peat deposits in Panama can reach depths of up to 9.45 m41.

The raw data provided in this data descriptor enable users to: i) develop alternative models for estimating % Corg using multivariable approaches that incorporate additional soil properties (e.g., pHw, soil texture), ii) recalculate BGCdS estimates using different depth intervals or correction factors, and iii) compare carbon stock estimates across different methodological approaches. These capabilities are particularly valuable for regional carbon accounting and validation of remote sensing products for wetland carbon mapping.

Users should note that the linear regression models presented here were developed specifically for Panama’s mangrove and forested wetland conditions. Application to other geographic regions should be validated with local calibration data.

Code availability

No code was developed or used for this manuscript.

References

Griscom, B. W. et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 11645–11650, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1710465114 (2017).

Seddon, N. et al. Global recognition of the importance of nature-based solutions to the impacts of climate change. Glob. Sustain. 3, e15, https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2020.8 (2020).

Taillardat, P., Friess, D. A. & Lupascu, M. Mangrove blue carbon strategies for climate change mitigation are most effective at the national scale. Biol. Lett. 14, 20180251, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0251 (2018).

Leifeld, J. & Menichetti, L. The underappreciated potential of peatlands in global climate change mitigation strategies. Nat. Commun. 9, 1071, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03406-6 (2018).

Pan, Y. et al. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science 333, 988–993, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201609 (2011).

Donato, D. C. et al. Mangroves among the most carbon-rich forests in the tropics. Nat. Geosci. 4, 293–297, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1123 (2011).

Bunting, P. et al. Global Mangrove Extent Change 1996–2020: Global Mangrove Watch Version 3.0. Remote Sens. 14, 3657, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14153657 (2022).

Alongi, D. M. Impacts of Climate Change on Blue Carbon Stocks and Fluxes in Mangrove Forests. Forests 13, 149, https://doi.org/10.3390/f13020149 (2022).

Spalding, M. D. & Leal, M. The State of World’s Mangroves 2022. (Global Mangrove Alliance, 2022).

Hagger, V. et al. Drivers of global mangrove loss and gain in social-ecological systems. Nat Commun 13, 6373, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33962-x (2022).

Page, S. E., Rieley, J. O. & Banks, C. J. Global and regional importance of the tropical peatland carbon pool. Glob. Chang. Biol. 17, 798–818, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02279.x (2011).

Global Peatlands Initiative. Global Peatlands Assessment – The State of the World’s Peatlands: Evidence for Action toward the Conservation, Restoration, and Sustainable Management of Peatlands. https://www.unep.org/resources/global-peatlands-assessment-2022 (2022).

Ministerio de Ambiente. Cuarta Comunicación Nacional Sobre Cambio Climático de Panamá. 273 https://transparencia-climatica.miambiente.gob.pa/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/4CNCC_2023_L.pdf (2023).

Ministerio de Ambiente. Segunda Contribución Determinada a Nivel Nacional (CDN2). 227 https://unfccc.int/documents/639822 (2024).

Ministerio de Ambiente. Informe Ejecutivo del Mapa de Cobertura Boscosa y Uso de Suelo 2021. 35 (2022).

Bunting, P. et al. The Global Mangrove Watch—A New 2010 Global Baseline of Mangrove Extent. Remote Sens. 10, 1669, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10101669 (2018).

Giri, C. et al. Status and distribution of mangrove forests of the world using earth observation satellite data. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 20, 154–159, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00584.x (2011).

Sanderman, J. et al. A global map of mangrove forest soil carbon at 30 m spatial resolution. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 055002, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aabe1c (2018).

Lawson, I. T. et al. Improving estimates of tropical peatland area, carbon storage, and greenhouse gas fluxes. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 23, 327–346, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-014-9402-2 (2015).

Kauffman, J. B. & Donato, D. C. Protocols for the Measurement, Monitoring and Reporting of Structure, Biomass and Carbon Stocks in Mangrove Forests. https://doi.org/10.17528/cifor/003749 (2012).

Howard, J., Hoyt, S., Isensee, K., Pidgeon, E. & Telszewski, M. Coastal Blue Carbon: Methods for Assessing Carbon Stocks and Emissions Factors in Mangroves, Tidal Salt Marshes, and Seagrass Meadows. Conserv. Int. Intergov. Oceanogr. Comm. UNESCO, Int. Union Conserv. Nature. Arlington, Virginia, USA. 1–180 (2014).

Cifuentes Jara, M. et al. Manual Centroamericano Para La Medición de Carbono Azul En Manglares. (CATIE, Turrialba, Costa Rica).

Romero, T. E. Resultados Finales de La Implementación Del Protocolo de Medición de Carbono En Ecosistemas de Manglares En Los Distritos de Remedios, San Félix y San Lorenzo, Provincia de Chiriquí. Proyecto Protección de Reservas y Sumideros de Carbono En Los Manglares. (PNUD-MiAMBIENTE, Ciudad del Saber, Panamá, 2017).

Upton, A., Vane, C. H., Girkin, N., Turner, B. L. & Sjögersten, S. Does litter input determine carbon storage and peat organic chemistry in tropical peatlands? Geoderma 326, 76–87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.03.030 (2018).

Rabel, E. A. & Loisel, J. The spatial distribution and paleoecology of Caribbean peatlands. Commun Earth Environ 5, 722, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01903-9 (2024).

Kauffman, J. B., Warren, M., Donato, D. C., Murdiyarso, D. & Kurnianto, S. Protocols for the Measurement, Monitoring, & Reporting of Structure, Biomass and Carbon Stocks in Tropical Peat Swamp Forest FIELD HANDBOOK. https://doi.org/10.17528/cifor/003749 (2011).

Hoyos-Santillan, J. et al. Quality not quantity: Organic matter composition controls of CO2 and CH4 fluxes in neotropical peat profiles. Soil Biol. Biochem. 103, 86–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.08.017 (2016).

Hoyos-Santillan, J. et al. Getting to the root of the problem: litter decomposition and peat formation in lowland Neotropical peatlands. Biogeochemistry 126, 115–129, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-015-0147-7 (2015).

Hoyos-Santillan, J. et al. Plot and landscape-level estimates of tree biomass and carbon stocks in Panama’s mangrove Important Bird Areas. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28330115 (2025).

Hoyos-Santillan, J. Controls of carbon turnover in lowland tropical peatlands. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.3387.2329 (The University of Nottingham, 2014).

Joosten, H. & Clarke, D. Wise Use of Mires and Peatlands: Background and Principles Including a Framework for Decision-Making. (International Mire Conservation Group and International Peat Society, Saarijärvi, Finland, 2002).

Sjögersten, S. et al. Coastal wetland ecosystems deliver large carbon stocks in tropical Mexico. Geoderma 403, 115173, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115173 (2021).

Ministerio de Ambiente. Inventario Nacional Forestal y de Carbono de Panamá Resultados de La Fase Piloto 2013-2015. 44 (2015).

Hoyos-Santillan, J. et al. Soil carbon stock densities in mangrove and forested wetland ecosystems of Panama. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28587746 (2025).

Kauffman, J. B., Heider, C., Cole, T. G., Dwire, K. A. & Donato, D. C. Ecosystem Carbon Stocks of Micronesian Mangrove Forests. Wetlands 31, 343–352, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-011-0148-9 (2011).

Howard, P. J. A. & Howard, D. M. Use of organic carbon and loss-on-ignition to estimate soil organic matter in different soil types and horizons. Biol. Fertil. Soils 9, 306–310, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00634106 (1990).

Howard, P. J. A. The Carbon-Organic Matter Factor in Various Soil Types. Oikos 15, 229–236, https://doi.org/10.2307/3565121 (1965).

The Global Mangrove Alliance. Global Mangrove Watch. (2022).

Maxwell, T. L. et al. Global mangrove soil organic carbon stocks dataset at 30 m resolution for the year 2020 based on spatiotemporal predictive machine learning. Data in Brief 50, 109621, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2023.109621 (2023).

Morrissette, H. K. et al. Belize Blue Carbon: Establishing a national carbon stock estimate for mangrove ecosystems. Science of The Total Environment 870, 161829, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161829 (2023).

Cohen, A. D., Raymond, R., Ramirez, A., Morales, Z. & Ponce, F. The Changuinola peat deposit of northwestern Panama: a tropical, back-barrier, peat(coal)-forming environment. Int. J. Coal Geol. 12, 157–192, https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-5162(89)90050-5 (1989).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the National Audubon Society, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), and Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute through the project “Valuing, Protecting and Enhancing Coastal Natural Capital in Panama (PN-T1233)/Blue Natural Heritage” funded by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) UK Blue Carbon Fund. J.H.S., J.C., A.I., and I.C. acknowledge support from SENACYT Grant PFID-FID-2021-114, Project “Hidrología, Reservas de Carbono, Plantas y Peces de Matusagaratí”, and from the Panamanian Ministry of Environment through research permits ARB-012-2022, ARB-002-2022, and ARB-112-2024. J.H.S and B.M.Y. acknowledge support from the European Union’s H2020 Research and innovation programs under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 101007950 (DecisionES) and 101059498 (Eco2adapt). The authors thank Gabriel Jácome, Eric Brown, Alexis Baules, Rodolfo Flores, Idaura Mepaquito, Celibeth Sánchez, Gisele Peñaloza, Kevin Madrid, Juan Marín, Aldair Vega, Yuheimy Castillo, Diana Castillo, Reyharth Berne Solís, Ronald Rodríguez, Karen Domínguez, Evelyn Jaén, Sozimo Villalobos, Johny Pardo, Generino Batista, Manuel Saez, and Gabriel Jaramillo for field and laboratory support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and investigation: J.H.S., J.C.; fieldwork and laboratory analyses: J.H.S., J.C., L.M.C.B., J.E.V., A.S., J.M., B.L., I.C., A.I., E.M.P.; data analysis: J.H.S., J.C., J.E.V., A.S., B.L., B.M.Y.; writing, review, and editing: J.H.S., E.G.M., B.M.Y.; funding acquisition: J.H.S., J.C., L.M.C.B., J.M., B.L., I.C., A.I., E.G.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoyos-Santillan, J., Chavarría, J., Castillo-Bethancourt, L.M. et al. Soil carbon stock densities in mangrove and forested wetland ecosystems of Panama. Sci Data 12, 1605 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05877-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05877-x