Abstract

The YOTO (You Only Think Once) dataset presents a human electroencephalog- raphy (EEG) resource for exploring multisensory perception and mental imagery. The study enrolled 26 participants who performed tasks involving both unimodal and multimodal stimuli. Researchers collected high-resolution EEG signals at a 1000 Hz sampling rate to capture high-temporal-resolution neural activity related to internal mental representations. The protocol incorporated visual, auditory, and combined cues to investigate the integration of multiple sensory modalities, and participants provided self-reported vividness ratings that indicate subjec- tive perceptual strength. Technical validation involved event-related potentials (ERPs) and power spectral density (PSD) analyses, which demonstrated the reli- ability of the data and confirmed distinct neural responses across stimuli. This dataset aims to foster studies on neural decoding, perception, and cognitive mod- eling, and it is publicly accessible for researchers who seek to advance multimodal mental imagery research and related applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental imagery is an important component of human cognition and has value in many application domains. Mental imagery refers to an internal process in which perception- like representations of objects, scenes, events, or sensations emerge without direct external inputs1. Studies suggest that these internally generated representations acti- vate neural substrates that also respond to actual perception, indicating that mental imagery functions as a neural simulation of real sensory experiences2,3.

Among the various types of mental imagery, visual imagery has been studied in a more extensive way4. Previous research has shown that visual imagery activates early visual cortical areas (V1–V4) and is closely associated with spatial reasoning, visual memory, and visual creativity5,6. Auditory imagery engages the auditory cor- tex (A1)7, which plays an essential role in music memory, language comprehension, and speech learning processes. Motor imagery, associated with the motor cortex (M1), is frequently used in athletic training8, motor skill enhancement, and rehabilitation therapies to improve muscle coordination and precision of movement9. Beyond these widely studied types, olfactory imagery involves the olfactory cortex and related lim- bic structures, such as the piriform cortex and amygdala, and can trigger emotional and autobiographical memory activation10,11. Tactile imagery helps mentally recon- struct the sense of touch, including temperature, texture, and pressure12. Gustatory imagery activates the insular cortex and is closely related to emotional regulation and appetite control13. Emotional imagery involves emotional processing regions, including the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and has been applied effectively in treatments for psychological disorders such as post-traumatic stress disor- der (PTSD) and anxiety disorders14,15. Importantly, different types of mental imagery often co-occur in naturalistic settings. Neuroimaging findings suggest that these inter- nally generated sensations partially recruit the same neural substrates that process real sensory input1,16. Mental imagery, in essence, is not merely symbolic or abstract representation; rather, on multiple levels, it simulates the brain’s response to actual perception. However, mental imagery does not occur exclusively in task-specific states; even in the absence of external stimuli, the brain remains highly active during rest- ing states, particularly in the medial prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex/precuneus, and the lateral cortical regions, which consistently exhibit coordinated activity during rest17,18. This network, known as the default mode network (DMN), is closely related to memory recall19, mind wandering and daydreaming20, memory retrieval, self-referential thought, and mental simulation21,22,23.

Researchers have applied neural representations of mental imagery in electroen- cephalography (EEG) decoding technologies. The neural mechanisms of mental imagery include sensory simulation, memory retrieval, and internal thought regula- tion, and these mechanisms illuminate how the brain reconstructs sensory experiences in the absence of external inputs4,24. Studies indicate that mental imagery produces measurable EEG patterns, such as alpha-wave changes and altered occipital gamma waves25,26. These neural markers suggest that EEG signals offer a promising means to recognize and classify mental imagery without relying on external stimuli. Visual imagery appears in alpha-wave modulation and changes in gamma-band activity in occipital regions25,26. Auditory imagery involves cortical areas linked to auditory pro- cessing. Motor imagery modulates sensorimotor rhythms and aids rehabilitation and motor control. Each imagery type reflects distinct neural patterns, and EEG signals detect these patterns in real time. The ability to capture such activity advances inter- active technologies that integrate mental imagery for communication or control. Most studies focus on unimodal sensory imagery, such as purely visual or auditory forms. Research on multisensory integration remains less extensive27. Concurrent processing of visual, auditory, and tactile imagery needs better understanding of neural mecha- nisms that integrate these modalities. Mental imagery EEG datasets also encounter technical constraints. A low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and high interindividual vari- ability limit reproducibility of research findings28. Methods lack uniform standards, which complicates generalization of decoding results29. Observing EEG signals dur- ing mixed imagery tasks may clarify how the brain coordinates and merges several internal simulations.

The YOTO (You Only Think Once) dataset holds strong potential for advancing research into the neural mechanisms of mental imagery and resting-state brain activity. It provides a rich collection of non-invasive EEG recordings during multimodal mental imagery tasks and spontaneous rest from a diverse group of participants. We anticipate a wide range of applications for this dataset. For instance, it can be used to develop and evaluate EEG-based decoding models of imagined sensory experiences, investigate and compare dynamics of perceived and imagined sensory responses, and explore the integration of multisensory representations. In sum, YOTO complements existing EEG resources by providing a high-quality, systematically curated dataset tailored to the study of internal mental states and multimodal cognitive process.

Methodology

Participants

Twenty healthy participants (14 males, 6 females) volunteered to participate in the study, with a mean age of 23.3 years (median: 23 years, range: 20–36 years). All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and provided their written informed consent prior to the experiment. Exclusion criteria included screen-induced dizziness, major diseases, irregular sleep patterns, poor sleep quality, disability, psy- chiatric disorders, or pregnancy. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee for Human Subject Protection, National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan (protocol No. NCTU-REC-108–128F; approval date: 31 March 2020; valid until 31 January 2023). All participants provided written informed consent for both participation and public sharing of anonymized EEG data.

EEG data acquisition

EEG signals were recorded in an electromagnetically shielded chamber using a high- fidelity electrophysiological recording system. The Polhemus 3SPACE FASTRAK system was used to position the Cz reference point before securing the EEG headset (Fig. 1). Thirty-two electrodes, including two reference electrodes at A1 and A2, were placed according to the 10–20 international system. Thirty-channel EEG signals were amplified and transmitted to a computer via a SynAmps RT 64 channel amplifier (Compumedics Neuroscan), digitized at 1000 Hz, and event markers were transmit- ted via a parallel port to indicate the onset of the trial, stimulus presentation, resting phase, and imagery phases.

Experimental protocol

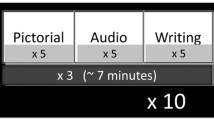

Each participant completed two separate sessions on different days, each session con- sisting of four blocks of 48 trials, interspersed with short breaks (Fig. 2). During the experiment, participants were instructed to keep fixation on a central cross while participating in mental imagery tasks associated with the stimuli presented.

Each trial followed a structured sequence, as shown in Table 1, beginning with a fixation period (2 s), during which the participants focused on a central cross to clear their thoughts. This was followed by a stimulus presentation phase (2 s), in which a visual, auditory, or combined stimulus was randomly displayed. Subsequently, the participants entered the imagery phase (4 s), during which they mentally visualized the stimulus received previously. Finally, during the self-report phase, participants rated the vividness of their mental imagery on a scale from 1 to 5. The duration of this phase varied across individuals. To assess baseline neural activity, resting-state EEG data were recorded both before and after the experimental session.

Stimuli details

In the imagery task, visual and auditory stimuli were presented, individually or in combination, to ensure a complete examination of sensory processing.

The visual stimuli included a gray square (Fig. 3) and two neutral-expression facial images (one male, one female) taken from the Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF) dataset30. The auditory stimuli included three human short vowels (/a/, /i/, /o/) and three piano tones (C: 261.63 Hz, D: 293.66 Hz, E: 329.63 Hz). These stimuli were systematically combined to create 27 unique stimulus conditions, which encompassed three categories: visual-only, auditory-only, and multimodal (visual-auditory) stimuli. To ensure a balanced distribution of stimuli in trials, a weighted randomization strategy was implemented (Table 2, Trials/Block). This weighted randomization approach prevented overrepresentation of specific conditions while maintaining sufficient exposure to all stimulus types, ensuring a balanced and unbiased experimental design.

Data preprocessing pipeline

Preprocessing of the EEG data was carried out using EEGLAB v202231 to ensure the integrity of the signal and the mitigation of artifacts. A causal FIR filter was used for bandpass filtering between 1 and 50 Hz, with a filter order of 500 and a buffer size of 30 seconds, effectively attenuating low-frequency drifts and high-frequency noise while preserving relevant neural oscillations. The data were subsequently resampled at 250 Hz to optimize computational efficiency while maintaining the fidelity of the recorded neural activity.

To address non-neural artifacts, artifact subspace reconstruction (ASR)32 was applied with a threshold parameter as suggested in33, which adaptively detects and reconstructs segments exhibiting excessive deviation from the statistical distribution of clean EEG data. The choice of the threshold parameter in ASR is essential for balancing between high-amplitude artifact removal and signal preservation, ensuring that transient high-amplitude artifacts (e.g. muscle activity, electrode displacement) are mitigated without excessively attenuating valid neural signals. Lower k values would result in overly aggressive rejection of artifacts, potentially removing informative neural activity, while higher values might allow significant artifacts to persist.

Following high-amplitude artifact correction, independent component analysis (ICA)34 with linear interpolation was performed to decompose the multichannel EEG signals into statistically independent sources, facilitating the isolation of neural components from non-neural artifacts. Finally, ICLabel35, a machine learning-based independent component classification tool, was utilized to automatically identify and remove artifacts related to ocular and muscular activities. Components classified as artifacts with a confidence probability greater than 0.8 were excluded from further analysis. This procedure effectively improved the SNR, ensuring that the retained components predominantly reflect neural activity.

Data Records

The dataset is publicly available on OpenNeuro36. The raw EEG recordings, stored in a BIDS-compliant structure, have been publicly released via https://doi.org/10.18112/openneuro.ds005815.v2.0.1. The data of each subject are organized in indi- vidual folders under /sub-<participant id>/eeg/, which contain raw EEG files in BrainVision format, including.vhdr,.eeg and.vmrk files for each session.

A separate /derivatives/ directory includes the processed EEG data used in technical validation. These files were preprocessed using a pipeline comprising a 1–50 Hz bandpass filter, resampling to 250 Hz, artifact subspace reconstruction (ASR), and independent component analysis (ICA), in order to ensure data quality and reduce artifacts prior to further analysis.

Technical Validation

To ensure the reliability and validity of the dataset, we conducted both behavioral and neurophysiological analyzes. Subjective vividness ratings were assessed to evalu- ate participants’ self-reported imagery experiences under different stimulus conditions. In parallel, neural responses were examined using event-related potentials (ERPs) to capture time-locked brain activity and power spectral density (PSD) analysis to char- acterize frequency-domain neural oscillations. These analyses were performed to visualize neural responses across experimental conditions.

Vividness ratings analysis

Figure 4 presents the distribution of vividness ratings across different stimulus condi- tions. A three-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to analyze the effects of subject, stimulus condition, and session. Significant main effects were observed for subject (F = 239.54, p < 0.001), stimulus condition (F = 4.04, p < 0.001), and the session (F = 14.61, p < 0.001). Interaction effects between the stimulus condition and the subject (F = 3.51, p < 0.001) and the subject and the session (F = 16.21, p < 0.001), while the interaction between stimulus condition and session (F = 0.67, p = 0.896)was not significant. A significant three-way interaction (F = 1.16, p = 0.009) was also observed. Self-report durations during the vividness rating phase were also recorded. Across all subject × session pairs, the minimum duration was 454.54 ms, the maximum was 5434.53 ms, the mean was 1515.24 ms, and the standard deviation was 1092.57 ms.

Distribution of Subjective Imagery Vividness Ratings Across Stim- ulus Conditions. Violin plot depicting the distribution of participant-rated vividness of mental imagery across different stimulus conditions. The horizontal axis categorizes auditory-only, visual-only, and multimodal stimuli, while the vertical axis indicates vividness ratings from 1 to 5.

Event-related potentials (ERP) analysis

Figures 5–7 show the ERP waveforms across stimulus conditions.

Event-Related Potentials (ERP) Waveforms for Visual Stimuli. ERP waveforms elicited by visual stimuli (male faces, female faces, and squares) at FCz, Cz, and Pz electrode sites. Facial stimuli evoke stronger neural responses compared to non-facial shapes, reflecting specialized neural processing of face perception.

The ERP of the visual stimuli, as illustrated in Fig. 5, shows the waveform distributions of the visual stimuli, including male faces, female faces, and squares. The ERP waveforms for face stimuli show higher amplitudes at FCz, Cz, and Pz electrodes compared to non-facial stimuli.

The ERP of the auditory stimuli, depicted in Fig. 6, compare neural responses to vocal and musical stimuli.

The ERP of the mixture stimuli, shown in Fig. 7, illustrate the waveform char- acteristics of combined visual and auditory stimuli.

When comparing the differences in power spectral density (PSD) of brain waves between various types of imagined activities and the baseline condition (Fixation) (Fig. 8), significant regional brain wave characteristics were observed in mixed visual, auditory and audiovisual imagery.

Power Spectral Density (PSD) Differences between Imagery Tasks and Baseline Fixation. Comparative PSD analysis illustrating EEG spectral changes between imagery conditions (visual, auditory, multimodal) and baseline fix- ation. Visual imagery significantly enhances Alpha oscillations in the occipital lobe; auditory imagery primarily boosts Theta activity centrally; multimodal imagery broadly elevates neural oscillations across frequency bands.

Visual imagery (Fig. 8a) primarily activated the enhancement of alpha wave responses in the occipital lobe, while auditory imagery (Fig. 8b) showed a more pronounced enhancement of Theta waves in the central, frontal and parietal regions. Mixed audiovisual imagery (Fig. 8c) showed significant changes in all frequency bands, with wave enhancements that significantly exceeded those of single-modality stimuli

In Fig. 9a, it can be seen that Delta and Theta waves show significant reductions in the frontal region, with the reduction in Theta waves being more prominent. In contrast, the Alpha and Beta waves exhibit significant enhancements in the occipital lobe (O1, O2, Oz).

Power Spectral Density (PSD) Differences Among Various Imagery Conditions. Comparative PSD analyses highlighting neural spectral differences between (a) visual versus auditory imagery, (b) multimodal versus visual imagery, and (c) multimodal versus auditory imagery. Results underscore distinctive neural activa- tion patterns across different brain regions and frequency bands, notably heightened Alpha and Beta activities in multimodal imagery.

In Fig. 9b, the Delta waves show a slight enhancement in the occipital lobe, while the Theta waves demonstrate a significant improvement in the central (Cz) and parietal (Pz) regions. Alpha waves also show slight enhancement in the occipital lobe, while beta waves exhibit enhancement in the frontal and central regionsIn Fig. 9c, the Delta waves show an improvement in the occipital lobe, with negli- gible differences in the central and frontal regions. Theta waves demonstrate significant enhancement in the central region, with minimal differences in the frontal region. Alpha waves show significant enhancement in the occipital and parietal regions, while beta waves exhibit significant enhancement in the frontal and central regions with- out any noticeable reductions.

The dataset includes EEG signals recorded from both resting-state and task phases, providing complete coverage for further analysis.

Code availability

The source code used for all technical validations conducted in this experiment has been uploaded and is publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/CECNL/YOTO_You_Only_Think_Once).

References

Kosslyn, S. M., Ganis, G. & Thompson, W. L. Neural foundations of imagery. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 635–642 (2001).

Lang, P. J. Imagery in therapy: an information processing analysis of fear. Behav. Ther. 8(5), 862–886 (1977).

Lang, P. J. A bio-informational theory of emotional imagery. Psychophysiology 16(6), 495–512 (1979).

Pearson, J., Naselaris, T., Holmes, E. A. & Kosslyn, S. M. Mental imagery: functional mechanisms and clinical applications. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19, 590–602 (2015).

Coyle, S. M., Ward, T. E. & Markham, C. M. Brain–computer interface using a simplified functional near-infrared spectroscopy system. J. Neural Eng. 4, 219 (2007).

Lawhern, V. J. et al. EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG- based brain–computer interfaces. J. Neural Eng. 15, 056013 (2018).

Tian, X., Ding, N., Teng, X., Bai, F. & Poeppel, D. Imagined speech influences perceived loudness of sound. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 225–234 (2018).

Jeannerod, M. Neural simulation of action: a unifying mechanism for motor cognition. Neuroimage 14, S103–S109 (2001).

Borst, G. & Kosslyn, S. M. Visual mental imagery and visual perception: structural equivalence revealed by scanning processes. Mem. Cognit. 36, 849–862 (2008).

Bensafi, M., Sobel, N. & Khan, R. M. Hedonic-specific activity in piriform cortex during odor imagery mimics that during odor perception. J. Neurophysiol. 98(6), 3254–3262 (2007).

Schlintl, C., Zorjan, S. & Schienle, A. Olfactory imagery as a retrieval method for autobiographical memories. Psychol. Res. 87(3), 862–871 (2023).

Lacey, S. & Sathian, K. Crossmodal and multisensory interactions between vision and touch. In Scholarpedia of Touch, 301–315 (2015).

Kobayashi, M. et al. Functional mapping of gustatory neurons in the insu- lar cortex revealed by pERK-immunohistochemistry and in vivo optical imaging. Synapse 64(4), 323–334 (2010).

Holmes, E. A., Geddes, J. R., Colom, F. & Goodwin, G. M. Mental imagery as an emotional amplifier: application to bipolar disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 46(12), 1251–1258 (2008).

Ji, J. L., Heyes, S. B., MacLeod, C. & Holmes, E. A. Emotional mental imagery as simulation of reality: fear and beyond—a tribute to Peter Lang. Behav. Ther. 47(5), 702–719 (2016).

Kosslyn, S. et al. Brain rCBF and performance in visual imagery tasks: common and distinct processes. Eur. J. Cogn. Psychol. 16(5), 696–716 (2004).

Kosslyn, S. M. & Ochsner, K. N. In search of occipital activation during visual mental imagery. Trends Neurosci. 17, 290–292 (1994).

Buckner, R. L., Andrews-Hanna, J. R. & Schacter, D. L. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1124, 1–38 (2008).

Conway, M. A. & Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychol. Rev. 107(2), 261 (2000).

Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. The science of mind wandering: empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66(1), 487–518 (2015).

Zatorre, R. J. & Halpern, A. R. Mental concerts: musical imagery and auditory cortex. Neuron 47, 9–12 (2005).

Zhang, D. & Raichle, M. E. Disease and the brain’s dark energy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 15–28 (2010).

Fox, K. C. R., Spreng, R. N., Ellamil, M., Andrews-Hanna, J. R. & Christoff, K. The wandering brain: meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of mind- wandering and related spontaneous thought processes. Neuroimage 111, 611–621 (2015).

Ganis, G., Thompson, W. L. & Kosslyn, S. M. Brain areas underlying visual mental imagery and visual perception: an fMRI study. Cogn. Brain Res. 20, 226–241 (2004).

Pfurtscheller, G. & Neuper, C. Motor imagery and direct brain–computer com- munication. Proc. IEEE 89, 1123–1134 (2001).

Schlegel, A. et al. Network structure and dynamics of the mental workspace. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 16277–16282 (2013).

Hubbard, T. L. Auditory imagery: empirical findings. Psychol. Bull. 136, 302 (2010).

Cichy, R. M., Pantazis, D. & Oliva, A. Resolving human object recognition in space and time. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 455–462 (2014).

Keogh, R. & Pearson, J. The blind mind: no sensory visual imagery in aphantasia. Cortex 105, 53–60 (2018).

Lundqvist, D., Flykt, A. & Öhman, A. The Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF) [dataset]. Karolinska Institutet, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychology Section. https://doi.org/10.1037/t27732-000 (1998).

Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. EEGLAB (version 2022). Swartz Center for Computa- tional Neuroscience. Retrieved from https://eeglab.org (2022).

Kothe, C. A. E. & Jung, T.-P. Artifact removal techniques with signal reconstruc- tion. US Patent App. 14/895,440. Google Patents (2016).

Chang, C.-Y., Hsu, S.-H., Pion-Tonachini, L. & Jung, T.-P. Evaluation of artifact subspace reconstruction for automatic artifact components removal in multi-channel EEG recordings. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 67(4), 1114–1121 (2019).

Comon, P. Independent component analysis, a new concept? Signal Process. 36(3), 287–314 (1994).

Pion-Tonachini, L., Kreutz-Delgado, K. & Makeig, S. ICLabel: an automated electroencephalographic independent component classifier, dataset, and website. NeuroImage 198, 181–197 (2019).

Wei, C.-S. et al. A Human EEG Dataset for Multisensory Perception and Men- tal Imagery. OpenNeuro. https://doi.org/10.18112/openneuro.ds005815.v2.0.1 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the National Science and Technology Coun- cil (109-2222-E-009-006-MY3, 112-2321-B-A49-012 and 112-2222-E-A49-008-MY2); in part by the Healthy Longevity Global Grand Challenge Catalyst Award of National Academy of Medicine, USA, and Academia Sinica, Taiwan (AS-HLGC-113-06); in part by the National Health Research Institute, Taiwan (Grant NHRI-EX114-11418EC); and in part by the Higher Education Sprout Project of National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University and Ministry of Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chun-Shu Wei: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visu- alization, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration. Yan-Han Chang: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Edit- ing. Hsi-An Chen: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft, Data Curation. Min-Jiun Tsai: Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Project administration Chun-Lung Tseng: Investigation, Data Curation, Formal anal- ysis Ching-Huei Lo: Investigation, Data Curation Kuan-Chih Huang: Methodology, Data Curation, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, YH., Chen, HA., Tsai, MJ. et al. A Human EEG Dataset for Multisensory Perception and Mental Imagery. Sci Data 12, 1598 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05881-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05881-1