Abstract

The vetch aphid, Megoura crassicauda is a globally distributed, major agricultural pest of beans and other leguminous crops, causing significant economic losses yearly. Its rapid reproductive rate and capacity to develop resistance to diverse pesticides pose substantial control challenges. However, the absence of high-quality reference genomes has impeded deeper exploration of gene function and hindered the development of new management strategies. Here, we present the first chromosomal-level high-quality genome of M. crassicauda, generated by integrating short-read, PacBio long-read and Hi-C sequencing technologies. The final assembly spans 440.80 Mb, comprising 179 contigs with a contig N50 of 41.57 Mb, and 94.82% of the sequence was successfully anchored to 6 pseudo-chromosomes. We annotated 19,424 protein-coding genes and achieved 97.10% BUSCO completeness. This high-quality genome provides an essential genetic resource for elucidating M. crassicauda biology and facilitates the development of targeted management strategies against this pest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The vetch aphid, Megoura crassicauda, is a worldwide agricultural pest primarily infesting legumes and alfalfa plants including but not limited to Vicia faba, Pisum sativum, and Lathyrus quinquenervius1,2,3,4. Both nymphs and adults of M. crassicauda mostly preferentially feed on phloem sap from tender leaves and stems, inflicting greater damage on legumes and alfalfa than many co-occurring pests5 (Fig. 1). This feeding disrupts essential physiological processes in host plants, severely impairing growth, development, and reproductive stages—particularly flowering and fruiting3,6. Under heavy infestation, crops may wither and perish, resulting in substantial yield losses and quality degradation7. Additionally, M. crassicauda transmits multiple plant-pathogenic viruses among different crops6.

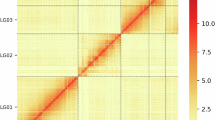

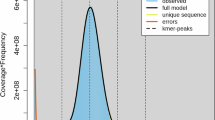

Genome assembly of Megoura crassicauda. (A) Morphology of M. crassicauda. (B) Genome scope profiles of 17-mer analysis. (C) Hi-C interactive heatmap of 6 linkage pseudo-chromosomes in M. crassicauda genome. Color indicates the intensity of the interaction signal. The darker the color, the higher the intensity. (D) Circle genome landscape of M. crassicauda. Circle a represents chromosomes, while circles b-e indicate gene density, DNA transposon density, long terminal repeat retrotransposon density and GC content of each respective chromosome, respectively.

As one significant legumes pest, M. crassicauda exhibits a broad global distribution with notable prevalence in China, Russia, the Korean Peninsula, and Japan2,3. Traditional strategies to control this pest mainly rely on insecticides, however, prolonged and excessive application accelerates resistance evolution of M. crassicauda to diverse pesticides while triggering adverse ecological consequences—including pesticide residues, environmental contamination, and suppression of natural enemies3,8,9,10. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms underpinning pesticide resistance is imperative for developing innovative management approaches for controlling this destructive pest. Nevertheless, the genetics of M. crassicauda remain poorly characterized. Existing research on M. crassicauda is largely confined to superficial biological investigations, lacking deeper exploration of gene function. Consequently, generating a high-quality reference genome is essential to advance genetic understanding and enable effective control of this pest.

Aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) represent a diverse insect group comprising over 4,700 described species globally11,12. Despite this diversity, whole-genome assemblies are available for only 86 species, with merely 22 sequenced to chromosomal resolution, and most of the remaining genomes remain at the scaffold, even contig levels13. Notably, genomes of considerable aphids feeding on main crops such as wheat, corn, cotton, sorghum have been fully obtained, including Diuraphis noxia14, Sitobion avenae15, Schizaphis graminum16, Rhopalosiphum padi17, Sitobion miscanthi18, Rhopalosiphum maidis19, Aphis gossypii20, Melanaphis sacchari21, Myzus persicae22, Eriosoma lanigerum23, with some species possessing multiple chromosomal assemblies. In contrast, genomic resources for legume-specialized aphids remain scarce: only Acyrthosiphon pisum13 and Aphis glycines24 have been sequenced. This critical genomic gap impedes fundamental research on legume aphids and constrains broader aphid studies. Generating a high-quality M. crassicauda genome is therefore imperative to advance research on its genetics, biology, and ecology, ultimately providing theoretical foundations for optimized management strategies against this significant pest.

In this study, we integrated short-reading sequencing, PacBio high-fidelity (HiFi) sequencing, and high-resolution chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) techniques to generate a high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly for M. crassicauda (Table 1). The assembly spans 440.80 Mb, comprising 179 contigs with a N50 length of 41.57 Mb (Table 2). The GC content was 29.77%, and 94.82% of the assembly was anchored to 6 chromosomes (Table 3). The predicted transposable elements and tandem repeats constituted 36.24% and 4.15% of the genome, respectively (Table 4). Furthermore, we predicted 19,687 protein-coding genes (Table 5), and annotated them against six databases: NR, InterPro, GO, KEGG, TrEMBL, and Swiss-Prot (Table 6). Above database annotation yielded the following gene counts: NR (19,352), TrEMBL (19,114), KEGG (19,154), InterPro (13,914), Swiss-Prot (12,100), and GO (8,233). (Table 6), respectively. Collectively, 19,424 genes received functional annotations, accounting for 98.66% of all protein-coding genes.

Methods

Sample material

Megoura crassicauda colony, originally collected in Anyang city (114°20′ E, 36°6′ N) of China, was reared on Vicia faba in laboratory under the control conditions of 25 ± 0.5 °C, relative humidity of 60 ± 5%, and a photoperiod of 16 h light: 8 h dark25. Before sampling, the adults were soaked in 1% sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 min, followed by rinsing in sterile water and immersion in 70% ethanol twice, and then washed in sterile water. Before extracting genomic DNA and RNA, the samples were quickly transferred to collection tubes, and were stored at − 80 °C after rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen.

Genomic size and heterozygosity were assessed using mixed DNA from 300 adults, and whole-genome sequencing was performed on PacBio sequel II platform. In addition, 500 adults were used for Hi-C library construction and sequencing, and more than 800 individuals including apterous and alate nymphs and adults at different development stages were used for transcriptome library construction and sequencing.

Genome sequencing

High-quality genomic DNA was extracted by CTAB method using QIAGEN® kit (QIAGEN, Germany) for DNA purification. Electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel (140 V, 15 min) was carried out with the extracted DNA to check for its purity and possible damage. Next, the samples’ purity was checked in a NanoDrop One (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and those where the spectral ratio of OD260/280 was 1.8–2.0 and OD260/230 2.0–2.2 were considered acceptable. Finally, the DNA concentration was measured using Invitrogen Qubit 4.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

For genome survey, fragments of DNA between 300 bp and 500 bp in length were formed using the Covaris ultrasonic disruptor and then the whole library was built through terminal repair, addition of the A-tail, sequencing adapter, purification, PCR amplification and similar steps. The constructed library was sequenced by using ‘PE150’ strategy on BGI MGISEQ platform (Beijing Genomics Institute, China). For long-reading sequencing, the genomic DNA was broken up by g-TUBEs (Covaris, USA), and only DNA fragments smaller than 15 kb were used in constructing the library. Then remove the single-stranded dangling sequence, repair the damaged DNA fragment, and add the A tail and the PacBio adaptor. The library was processed with the SMRTbell Enzyme Cleanup Kit (Pacific Biosciences, USA) and then purified by AMPure PB Beads. The target fragment was screened by blue pippin (Sage Science, USA). After that, purified library fragments were determined with Agilent 2100 (Agilent technologies, USA). All the sequencing was done using the PacBio Sequel II platform and Sequencing Primer V2 and Sequel II Binding Kit at Wuhan Gene Read Biotechnologies Co. Ltd.

The 1 g tissue was cross-linked with 1% final concentration of fresh formaldehyde for 10 min, afterward, the tissue was quenched with 5 min of 0.2 M glycine. The cross-linked cells were then lysed in the lysate. After that, 663 μL of DNase/RNase-free water, 120 μL of 10 × blunt-end ligation buffer, 100 μL of 10% Triton X-100, and 20 U of T4 DNA ligase were placed in the solution. Ligation took place at 16°C for a duration of 4 h. After ligation, the cross-linking was reversed overnight at 65 °C with 200 μg/mL protease K (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The DNA was purified using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The Hi-C library for Illumina sequencing was prepped by NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, England) according to manufacturer’s instructions26. The final library was sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform (San Diego, USA) with 150 bp paired-end reads.

Transcriptomic sequencing and analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the collected samples using TRIzol reagent (Termo Fisher Scientific, USA). RNA integrity, DNA contamination and purity were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer and NanoPhotometer (Implen, Germany), respectively. Oligo (dT) magnetic beads were used to enrich specific mRNAs. The synthesis of the first cDNA involved a fragmented mRNA as its template, and the second cDNA was synthesized from dNTPs. The purified double-stranded cDNA was subjected to end-repair, A-tailing, and sequencing adapter ligation. The cDNA of approximately 200 bp was screened with AMPure XP beads, and the PCR product was amplified and then purified with AMPure XP beads as well. The library was constructed by using Illumina’s NEBNext® UltraTM RNA Library Prep Kit (NEW ENGLAND BIOLABS, ENGLAND). The constructed library was preliminarily quantified using the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and detection was done using the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent technologies, USA). RT-qPCR was used to check the concentration of the library so that its quality could be verified.

After the examination and approval of the library, different libraries must meet the standards of effective concentration and data volume setting. DNA libraries were prepared used by the MiSeq and paired end reads of 150 base pairs were collected. The dataset was filtered with Fastp (v0.23.2)27 using the parameter ‘-cut _ front-cut _ tail-cut _ window _ size 4-a auto -cut _ mean _ quality 20 -length _ required 36’. An index was made for the reference genome, and the paired end clean reads were mapped against it with HISAT2 (v2.2.1)28 using these parameters: ‘-phred33-no-mixed-no-discordant’. Differential expression analysis between the two comparison combinations was performed using DESeq2 software (v1.16.1)29 with a filtering threshold of padj < 0.05 and |log2FoldChange| > 1. Benjamini and Hochberg’s method helped adjust the P value to make sure the false discovery rate stayed low.

Genome size estimation and assembly

We used SOAPnuke software (v2.1.0) to filter Raw reads30. Firstly, the reads containing the adaptor sequence were filtered out. Then the duplicated reads caused by PCR amplification were removed. When the content of N in one end of the sequencing read exceeds 10% of the read length ratio or the number of low-quality (< = 5) bases exceeds 50% of the read length ratio, this paired reads need to be removed, and finally clean reads were obtained. The main parameters were: -lowQual = 20, -nRate = 0.005, -qualRate = 0.5, and other parameters were default. Then, we used FastQC software (v0.12)31 to evaluate the quality of sequencing from the following four aspects: 1) quality inspection of sequencing data; 2) sequencing error rate distribution check; 3) Base frequency distribution check; 4) GC content distribution inspection. The K-mer count and statistics of the sequence files were performed by GCE software (v1.0.2)32 to estimate the genome size, heterozygosity, and repetition. Genome assembly was performed using hifiasm (v0.14.2)33. The final genome draft was obtained by dehybridization of the corrected genome. In order to evaluate the integrity and consistency of the assembly, the software BWA (v0.7.17-r1188)34 was used to align the second-generation sequencing data back to the assembled genome, and the comparison rate of reads, the degree of coverage of the genome, and the distribution of depth were counted (98.42% mapping rate; 28.89 × ; 99.38% coverage). Finally, based on the single-copy homologous gene set in OrthoDB, BUSCO (v5.2.2)35 was used to predict these genes and calculate their integrity, fragmentation and possible loss rate. In this way, the integrity of the gene region in the entire chromosome-level genome was assessed.

The Hi-C analysis method was used to achieve genome assembly to the chromosome level26. Quality filtering of the genome using fastp (v0.23.2)27, the data removed includes filters mapped to the end of the genome and other unavailable data. The reads were mapped to polished genomes using BWA (v0.7.17-r1188)34 with default parameters. The paired reads are mapped to a different contig (or scaffold) to be used as Hi-C related scaffolds, and then the agglomerative hierarchical clustering method is further applied to the order and localization of the aggregated sequences in Lachesis. Then we used JuiceBox (v1.8.8)36 to correct the assembly errors in the visualization.

In this study, a 300–500 bp library of M. crassicauda sample was constructed on the Illumina platform. A total of 66.98 Gb clean reads were successfully sequenced. The sequencing quality was normal and the sequencing error rate was normal. NT library comparison results showed that there was no obvious exogenous pollution. K-mer analysis estimated the genome size to be 405.43 Mb. It was speculated that the heterozygosity of the genome was 1.72%, the proportion of repetitive sequences was 36.24%, and the GC content of the genome was about 31.85%. For long read sequencing, after filtering out low-quality data, we obtained 63.58 Gb of HiFi reads. The average lengths of HiFi reads and N50 were 15, 470 bp and 15, 142 bp, respectively. The final genome size obtained by genome assembly was 440.80 Mb, including 179 contigs with the 41.57 Mb of contig N50. The GC content was 29.77% (Tables 1, 2).

A total of 72.68 Gb clean reads were generated by Hi-C sequencing for genome assembly at the chromosome level. These reads were mapped to the genome, retaining 411, 704, 643 paired - end (PE) reads, of which 350, 328, 429 were valid interactive PE reads. Among the 179 contigs, 94.82% of the sequence length was anchored on 6 linkage groups, with lengths ranging from 22.38 Mb to 128.47 Mb and the average sequencing depth was 28.89 (Table 2).

Gene prediction and annotation

Genome prediction and annotation mainly includes three research directions: repeat sequence identification, non-coding RNA prediction, gene structure prediction and functional annotation. We will analyze from these three aspects.

Repetitive sequence annotation

The identification of repetitive sequences combines the homology prediction method based on the RepBase library (http://www.girinst.org/repbase) (software: RepeatMasker (vopen-4.0.9)37 and RepeatProteinMask (vopen-4.0.9)38) and the de novo prediction method based on self-sequence alignment (RepeatModeler (vopen-1.0.11)39) and repetitive sequence features (LTR-FINDER40). In addition, the de novo prediction method also uses Trf software (v4.09)41 to find Tandem Repeats in the genome.

Gene structure prediction

The gene structure prediction in this study used a combination of homology prediction, ab initio prediction, and RNA-seq-guided prediction. First, homology prediction involved the analysis of protein sequence files of closely related species on NCBI. Subsequently, the Exonerate (v2.4.0)42 was used to predict transcripts and coding regions based on alignment results. In this evaluation, hundreds of genomes were sampled using software BUSCO (v5.2.2)35, and genes with single-copy orthologs > 90% were selected to construct gene sets of 6 major phylogenetic branches as indirect homology evidence input. ab initio prediction was performed using software Augustus (v3.3)43, Genscan (v1.0)44, and GlimmerHMM (v3.0.4)45. For transcriptome prediction, RNA-seq data were compared by gmap (v2020-10-24)46, Stringtie (v2.1.1)47 and cd-hit (v4.8.1) to reconstruct the transcripts, and then use software TransDecoder (v5.7.0)48, PASA (v2.5.3)49 and other software to predict the coding frame. Finally, the gene evidence sets predicted by various methods are integrated and filtered to form a non-redundant and more complete gene set using MAKER (v3.00)50 software.

Gene function prediction

The proteins in the predicted gene set were functionally annotated using BLASTP and InterProScan based on the similarity of the foreign protein database (Swiss - Prot51, TrEMBL, KEGG52, InterPro53, GO54 and NR). In addition, we also used GlimmerHMM (v3.0.4)45 for domain prediction to obtain information about conserved sequences, motifs, and protein domains.

In the annotation process of non-coding RNA, according to the structural characteristics of tRNA, tRNAscan-SE (v1.3.1)55 software was used to find the tRNA sequence in the genome. Because rRNA is highly conserved, rRNA sequences of closely related species can be selected as reference sequences to search for rRNA in the genome by BLASTN alignment. In addition, using the covariance model of the Rfam family, the miRNA and snRNA sequence information on the genome can be predicted using INFERNAL software (v1.1.2) from the Rfam database56.

Repetitive sequences are an important part of the genome, which mainly include two categories: tandem repeats and interspersed repeats. The tandem repeat sequences include microsatellite sequences, small satellite sequences and so on; interspersed repeats sequences are also called transposable elements. In this study, a total of 156.93 Mb repetitive sequences were identified, in which a large proportion (33.93%) was composed of transposon, followed by Tandem repeat (4.15%) (Table 4). The number of repetitive sequences affects the size of the genome, and the proportion of unknown categories was relatively high, which may be due to the lack of research on hemipteran insects.

In this study, gene structure prediction uses a combination of three methods: homologous prediction, de novo prediction, and transcript prediction. A total of 19687 genes were annotated in this experiment. The average lengths of the gene, CDS, exons and introns were 7, 821.84 bp, 1, 382.38 bp, 285.02 bp and 1, 468.9 bp, respectively, and the average number of exons per gene was 5.3. In the 19687 genes that have been sequenced, we annotated a total of 19424 genes through multiple gene function databases, it accounted for 98.66% of the total number of genes annotated. (Table 5). There are 19352 genes in NR database and 19114 genes in TrEMBL database. In addition, 19154, 13914, 8233, and 12100 genes were annotated in KEGG, InterPro, GO and Swiss - prot databases (Table 6). We also annotated a total of 1092 non-coding RNAs, of which rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, and miRNA were 294, 657, 94, and 47, respectively (Table 7). Finally, we identified 97.1% of the genes in the BUSCO Insecta database (hemiptera _ odb10) (single - copy BUSCOs: 95.7%, duplicated BUSCOs: 1.40%), indicating that the genome has good assembly integrity (Table 8). In addition to assembly integrity, we also used BUSCO to evaluate the gene annotation results of the genome. The total number of genes that can be completely aligned with BUSCO was 2407, accounting for 95.9% of the total gene set. There were 2372 single-copy genes and 35 duplicated genes, accounting for 94.5% and 1.4% of the gene set, respectively. The number of genes that could not be compared with BUSCO profile was 99, accounting for 3.9% of the gene set.

Data Records

Genomic Illumina sequencing data, PacBio sequencing data and Hi-C sequencing data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession number PRJNA122693357. The final assembled Megoura crassicauda genome were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession number ASM5016992v158. The annotation files of the Megoura crassicauda genome have been deposited at figshare59.

Technical Validation

DNA integrity. The concentration of extracted DNA was done with the help of Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and QubitTM 3 Flurometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Obtained DNA absorbance was approximated at 260/ 280 nm and 260/ 230 nm measuring about 1.8. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used in the identification of the quality of genomic DNA. The key band size of the DNA fragments 23 K, the degradation band was over 5 K. The sample holes did not have contamination, which was a vivid indication of good integrity of the DNA molecules in the present study.

Data availability

All of data records mentioned in this study are available at the following URL: https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP565656; https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_050169925.1; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28490288.

Code availability

All bioinformatics tools and software used in this study are available in public databases and are implemented according to published bioinformatics tool manuals and protocols. This method describes the version and parameters of the software without using specific code or script. Custom code is not used.

References

Simon, J.-C. & Peccoud, J. Rapid evolution of aphid pests in agricultural environments. Current Opinion in Insect Science 26, 17–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2017.12.009 (2018).

Jiadong, Y. et al. Predation of Cheyletus malaccensis (Acari: Cheyletidae) on Megoura japonica (Hemiptera: Aphididae) under five different temperatures. International Journal of Acarology 45, 176–180, https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2019.1571527 (2019).

Trinh, D. N., Ha, T. K. L. & Qiu, D. Biocontrol Potential of Some Entomopathogenic Fungal Strains Against Bean Aphid Megoura japonica (Matsumura). Agriculture 10, 1–10 (2020).

Zhang, S., Cao, Z., Wang, Q., Zhang, F. & Liu, T.-X. Exposing eggs to high temperatures affects the development, survival and reproduction of Harmonia axyridis. Journal of Thermal Biology 39, 40–44, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2013.11.007 (2014).

Moran, N. A. The Evolution of Aphid Life Cycles. 37, 321-348, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.37.010192.001541 (1992).

Diaz, B. M., Oggerin, M., Lastra, C. C. L., Rubio, V. & Fereres, A. Characterization and virulence of Lecanicillium lecanii against different aphid species. BioControl 54, 825–835, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-009-9218-9 (2009).

Cheng, L.-Y., Zhang, Y., Chen, Z.-Z. & Xu, Y.-Y. Effects of constant and fluctuating temperatures on development and reproduction of Megoura crassicauda and Aphis craccivora (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Entomologica Fennica 29, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.33338/ef.70036 (2018).

Blair, A., Ritz, B., Wesseling, C. & Freeman, L. B. Pesticides and human health. Occupational and environmental medicine 72, 81–82, https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2014-102454 (2015).

Koch, R. L. et al. Efficacy of afidopyropen against soybean aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) and toxicity to natural enemies. Pest Management Science 76, 375–383, https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5525 (2020).

Ahmad, M. F. et al. Pesticides impacts on human health and the environment with their mechanisms of action and possible countermeasures. Heliyon 10, e29128, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29128 (2024).

von Dohlen, C. D., Rowe, C. A. & Heie, O. E. A test of morphological hypotheses for tribal and subtribal relationships of Aphidinae (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aphididae) using DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 38, 316–329, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.035 (2006).

Ge-xia, Q. et al. The International Aphid Genomics, C. Genome Sequence of the Pea Aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. PLOS Biology 8, e1000313, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000313 (2010).

Smith, T. E., Li, Y., Perreau, J. & Moran, N. A. Elucidation of host and symbiont contributions to peptidoglycan metabolism based on comparative genomics of eight aphid subfamilies and their Buchnera. PLOS Genetics 18(5), e1010195, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1010195 (2022).

Nicholson, S. J. et al. The genome of Diuraphis noxia, a global aphid pest of small grains. BMC Genomics 16, 429, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-1525-1 (2015).

Byrne, S. et al. Genome sequence of the English grain aphid, Sitobion avenae and its endosymbiont Buchnera aphidicola. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 12, jkab418, https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkab418 (2022).

Tamborindeguy, C. et al. Genomic and Proteomic Analysis of Schizaphis graminum Reveals Cyclophilin Proteins Are Involved in the Transmission of Cereal Yellow Dwarf Virus. PLOS ONE 8, e71620, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071620 (2013).

Thorpe, P., Escudero-Martinez, C. M., Cock, P. J. A., Eves-van den Akker, S. & Bos, J. I. B. Shared Transcriptional Control and Disparate Gain and Loss of Aphid Parasitism Genes. Genome Biology and Evolution 10, 2716–2733, https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evy183 (2018).

Jiang, X. et al. A chromosome-level draft genome of the grain aphid Sitobion miscanthi. GigaScience 8, giz101, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giz101 (2019).

Chen, W. et al. Genome sequence of the corn leaf aphid (Rhopalosiphum maidis Fitch). GigaScience 8, giz033, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giz033 (2019).

Jing, T. et al. A near-complete genome reveals the population evolution of the cotton-melon aphid Aphis gossypii. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 176, 104215, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2024.104215 (2025).

Zhang, J. et al. Whole-genome resequencing and transcriptome analysis provide insights on aphid-resistant quantitative trait loci/genes in Sorghum bicolor. Plant Breeding 140, 618–629, https://doi.org/10.1111/pbr.12946 (2021).

Mathers, T. C. et al. Rapid transcriptional plasticity of duplicated gene clusters enables a clonally reproducing aphid to colonise diverse plant species. Genome Biology 18, 27, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1145-3 (2017).

Biello, R. et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the woolly apple aphid, Eriosoma lanigerum Hausmann (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Molecular Ecology Resources 21, 316–326, https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13258 (2021).

Wenger, J. A. et al. Whole genome sequence of the soybean aphid, Aphis glycines. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 123, 102917, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2017.01.005 (2020).

Xie, Y. et al. The Stress Response of Aphids to the Accumulation of Heavy Metals Along Vicia faba L. Under Cadmium Treatment. Insects 15 (2024).

Rao, S. S. P. et al. A 3D Map of the Human Genome at Kilobase Resolution Reveals Principles of Chromatin Looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021 (2014).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 (2018).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nature Biotechnology 37, 907–915, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biology 15, 550, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Chen, Y. et al. SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. GigaScience 7, gix120, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/gix120 (2018).

Andrews, S. FastQC A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data (2014).

Binghang, L. et al. Estimation of genomic characteristics by analyzing k-mer frequency in de novo genome projects (2013).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature Methods 18, 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 (2015).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Juicebox.js Provides a Cloud-Based Visualization System for Hi-C Data. Cell Systems 6, 256–258.e251, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2018.01.001 (2018).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to Identify Repetitive Elements in Genomic Sequences. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 25, 4.10.11–14.10.14, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2009).

Tempel, S. in Mobile Genetic Elements: Protocols and Genomic Applications (ed Yves Bigot) 29-51 (Humana Press, 2012).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Research 35, W265–W268, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm286 (2007).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 27, 573–580, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.2.573 (1999).

Slater, G. S. C. & Birney, E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 6, 31, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-6-31 (2005).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Research 34, W435–W439, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl200 (2006).

Trapnell, C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology 28, 511–515, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1621 (2010).

Majoros, W. H., Pertea, M. & Salzberg, S. L. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics 20, 2878–2879, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bth315 (2004).

Wu, T. D. & Watanabe, C. K. GMAP: a genomic mapping and alignment program for mRNA and EST sequences. Bioinformatics 21, 1859–1875, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti310 (2005).

Shumate, A., Wong, B., Pertea, G. & Pertea, M. Improved transcriptome assembly using a hybrid of long and short reads with StringTie. PLOS Computational Biology 18, e1009730, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009730 (2022).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature Protocols 8, 1494–1512, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.084 (2013).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Research 31, 5654–5666, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkg770 (2003).

Holt, C. & Yandell, M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 491, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-491 (2011).

Bairoch, A. & Apweiler, R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Research 28, 45–48, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.45 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 28, 27–30, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Zdobnov, E. M. & Apweiler, R. InterProScan – an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 17, 847–848, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.847 (2001).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics 25, 25–29, https://doi.org/10.1038/75556 (2000).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: A Program for Improved Detection of Transfer RNA Genes in Genomic Sequence. Nucleic Acids Research 25, 955–964, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.5.955 (1997).

Griffiths-Jones, S. et al. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 33, D121–D124, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki081 (2005).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP565656 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_050169925.1 (2025).

Ji, J. Genome annotation information of Megoura crassicauda. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28490288 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32100390), the Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province (No. 252102110211), and the Major Science and Technology Projects in Anyang (2023A02NY002). Great gratitude goes to Dr. Erliang Yuan from Institute of Zoology of Chinese Academy of Sciences for the work at English editing and language polishing. We thank Prof. Gexia Qiao from Institute of Zoology (Chinese Academy of Sciences) for the aphid species identification and confirmation of Megoura crassicauda in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jichao Ji, Xiao Chang, Yuanchen Zhang conceived and supervised the project; Jichao Ji, Yuanchen Zhang, Yuhao Ban, and Ruimin Li performed the experiments; Yue Gao, and Jichao Ji analyzed the raw data; Xiaoyun Wang, Jingli Lv, and Miaomiao Xin evaluated the results and performed bioinformatic analyses; Yuanchen Zhang and Yue Gao wrote the original draft; Jingshun Wang, Jichao Ji, and Xiao Chang reviewed the original draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Gao, Y., Ban, Y. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of vetch aphid Megoura crassicauda (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Sci Data 12, 1597 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05883-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05883-z