Abstract

Longwave radiation (LWR) is a critical factor in surface energy balance and greenhouse effect studies, and its accurate measurement is essential for understanding climate change. However, existing remote sensing-based LWR products still have room for improvement in terms of spatiotemporal coverage, resolution, and accuracy. To address this issue, we developed the LWR Component of the global Long-term Earth System spatiotemporally Seamless Radiation budget dataset (LessRad). LessRad provides high-resolution (0.05°, hourly) LWR components including longwave downward radiation (LWDR), longwave upward radiation (LWUR), and longwave net radiation (LWNR). It extends the temporal coverage to 41 years (1982–2022) and outperforms existing comparable products. For LWDR and LWUR, rigorous validation against 565 ground-based observation sites demonstrates high accuracy, with correlation coefficients (R) of 0.94 and 0.97, biases of –4.39 W/m2 and –0.14 W/m2, and root mean square errors (RMSE) of 24.74 W/m2 and 20.42 W/m2, respectively. The high quality and extensive coverage make the LessRad LWR dataset an invaluable resource for fine-scale analysis of global surface radiation dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Surface longwave radiation (LWR), which comprises longwave upward radiation (LWUR), longwave downward radiation (LWDR), and longwave net radiation (LWNR), plays a crucial role in the Earth’s climate system. Its distribution and variability profoundly influence the surface energy balance, the greenhouse effect, and climate feedback mechanisms1,2. Accurate quantification of LWR is essential for assessing global warming, water vapor feedback, and cloud–surface interactions3,4. For most studies and applications, the optimal spatial resolution for LWDR is below 10 km, with temporal resolution ideally at sub-daily or even hourly intervals5,6. In recent years, advances in satellite remote sensing technology, data analysis, and climate modeling have led researchers to develop various LWR datasets aimed at characterizing their spatiotemporal distribution on different scales (Table 1). However, these products are still limited in terms of spatial resolution, temporal coverage, and observational continuity, making them inadequate for high-accuracy studies of LWR across different regions and timescales.

A variety of datasets have been used to observe and estimate mainly including reanalysis data, climate models, and satellite observations. Reanalysis datasets, such as the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Reanalysis v5 (ERA5), the Japanese 55-year Reanalysis (JRA-55), the Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS), and the Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2)7,8,9,10, are produced by assimilating multisource observations—including data from ground stations, radiosondes, and satellites—into data assimilation models11. These datasets can provide long-term and spatially complete records. Thus, they are widely used for large-scale climate monitoring and analysis. However, their spatiotemporal resolutions remain insufficient12 (Table 1). ERA5, as one of the most advanced reanalysis products, offers a spatial resolution of 0.25° and hourly global LWR information, ensuring good accuracy in most regions and periods. However, due to limited assimilated data or lower data quality, uncertainties may increase in complex terrains or extreme environments (e.g., mountainous regions and polar areas)12,13,14. ERA5-LAND offers ~9 km and hourly resolution, but it only covers land areas, lacking coverage of ocean regions11.

In addition, climate models are extensively used for simulating LW, and the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6)15 ensembles aggregate simulations from multiple global climate models to provide data on radiative fluxes at the top of the atmosphere (TOA) and the surface under historical and future scenarios. Compared to the TOA, earth system models exhibit greater uncertainties in simulating the surface radiation budget16. Errors in cloud-related parameters and inadequate representation of temperature and moisture profiles further reduce the LWR accuracy, and climate models continue to perform poorly in polar regions17,18,19.

In contrast, satellite observations offer distinct advantages in spatial and temporal resolution. Geostationary (GEO) satellites, such as the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES), FY-4A, and Himawari-8/9, provide extremely high temporal resolution—down to intervals of a few to ten minutes—enabling effective monitoring of rapid regional changes and diurnal cycles20,21,22. However, each GEO satellite is limited to observing a specific longitudinal zone (for example, GOES covers the Americas while Himawari covers the Asia-Pacific region23), and their records, mostly commencing in the mid-2010s, are too short to support long-term climate trend analyses.

Polar-orbiting satellites, such as the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), can provide relatively high spatial resolution (~1 km or ~5 km) observations on a global scale, along with reliable long-term records24. Although binary satellites are used for network observation, the limitation of overpass frequencies means that its temporal resolution is generally only four times per day or less, making it difficult to capture diurnal variations25. Moreover, cloud cover, polar conditions, and complex terrain can also result in discontinuous observations or reduced accuracy25. For example, the Global Land Surface Satellite (GLASS) product, which is based on MODIS calculations, is limited by the MODIS overpass frequency, yielding only high spatial resolution instantaneous observations that do not achieve seamless global coverage26. In contrast, the Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System Synthetics (CERES-SYN) provide hourly data. Still, its spatial resolution of 1° (~110 km) is too coarse to capture regional details or radiative differences over complex terrain23,27. Most satellite‐derived LWDR datasets are constrained by coarse spatial resolutions (≥100 km) and substantial uncertainties, which limit their ability to capture fine-scale variations28,29. For instance, GEWEX-SRB and ISCCP-FD offer spatial resolutions of approximately 110 km and 280 km, respectively, with a 3-hour temporal resolution and uncertainties exceeding 30 W/m2 30,31. Although the updated ISCCP-FH product has an improved spatial resolution of about 110 km, it remains inadequate.

The coarse resolution of global products, the limited temporal span of GEO satellite data, and the insufficient temporal frequency of polar-orbiting data restrict their applications in climate modeling, weather forecasting, and environmental monitoring. These limitations leave significant room for improvement in explaining and quantifying LWR variations across different scales.

To address the challenges of insufficient spatiotemporal resolution and short time series in LWR products, this study developed a globally covered, hourly-updated, full-component LWR dataset with an approximate spatial resolution of 5 km. Based on the previously computed LessRad LWDR (2002–2022) product, the dataset further integrates ERA5 reanalysis data and GLASS broadband emissivity data. By employing a random forest model and the Stefan–Boltzmann law, the full components of LWR (upward, downward, and net radiation) have been generated with seamless global continuous coverage over 41 years (1982–2022) and high accuracy.

Methods

Data sources and processing

Multi-source remote sensing and reanalysis datasets were used, with ground-based observational data employed as auxiliary information for performance evaluation and validation. All datasets used for calculation were first subjected to physical plausibility checks based on predefined physical thresholds. Subsequently, a difference-threshold-based screening method was applied: for each step, the difference between the current sample and the reference sample was calculated across all corresponding input and output parameters. If more than 75% of the parameters in a sample exceed their specified thresholds in difference, the entire sample is retained in the cleaned dataset. The initial reference was set as the first data record, and after each iteration, the newly retained sample became the updated reference for the next comparison. This data cleaning approach helps to preserve the diversity of both typical and extreme cases, thereby enhancing the representativeness of the dataset.

LessRad LWDR dataset

As part of the LessRad Dataset, the LessRad LWDR (2002–2022) dataset12 was developed using advanced LWDR parameterization32 and temporal scaling method25 based on instantaneous MODIS observations24 and ERA5 reanalysis data10. The previous version of the dataset provides high-accuracy hourly global LWDR data at a spatial resolution of 0.05° for the period 2002–202212. These data were interpolated for computational purposes onto the ERA5 reanalysis grid at a 0.25° resolution.

Reanalysis datasets

ERA5 is the fifth-generation reanalysis dataset from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, featuring a spatial resolution of 0.25° (~31 km) and an hourly temporal resolution10. This study employs total column water vapor (TCWV), skin temperature (ST), and LWDR from ERA5. For the period 1982–2001, the ERA5 data were bilinearly interpolated to a unified 0.05° grid with LessRad LWDR for the calculation of surface LWR.

GLASS broadband longwave emissivity

The broadband surface emissivity (BBE) data, spanning the spectral range from 8 to 13.5 μm33,34, serve as a key parameter for calculating LWUR. As part of the GLASS dataset derived from MODIS, the product is provided at 8-day and 5 km resolution. After reprojecting and resampling the data to the LessRad LWDR (2002–2022) spatial resolution, the emissivity values were further interpolated to an hourly scale by selecting the value from the nearest time node, thereby ensuring that all data sources are consistently matched on the same grid.

Ground-based measurements

Ground-based observational data from Baseline Surface Radiation Network (BSRN)35, Tropical Atmosphere Ocean (TOGA-TAO)36, AmeriFlux37, Coordinated Energy and Water Cycle Observation Project (CEOP)38, AsiaFlux39, and the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (TPDC)40 have undergone strict quality control. In total, data from 565 ground-based observation stations were used (Fig. 1), with details of the observation networks provided in Table 2. Depending on the validation requirements, these datasets were resampled to various temporal resolutions.

Method flow

In this study, a long-term, all-sky, full-component LWR dataset spanning 1982–2022 was constructed by integrating multi-source remote sensing and reanalysis data. Figure 2 provides a comprehensive illustration of the data inputs and model framework utilized in the dataset construction.

Calculation of LWDR

For 2002–2022, LWDR data were processed by integrating MODIS observations with ERA5 reanalysis. The MODIS instantaneous LWDR was calculated using the methodology proposed by Wang, et al.41. Initially, the deviation between MODIS instantaneous LWDR measurements and temporally corresponding ERA5 LWDR values was quantified. Subsequently, for intervals between consecutive MODIS overpass times, the averaged deviations were integrated with ERA5 LWDR data to generate a continuous LWDR time series. This processing yielded the LessRad LWDR product at 0.05° spatial and hourly temporal resolution for the 2002–2022 period12,42.

A Random Forest Regression (RFR) model that was employed to establish the relationship between ERA5 reanalysis variables (including LWDR, ST, and TCWV) and LessRad LWDR data (2002 to 2022)43 was used to estimate LWDR for the period 1982–2001. RFR is an ensemble model that constructs a large number of mutually independent decision trees, each of which makes independent predictions at its internal nodes based on randomly selected subsets of both the training data and feature space. The results of all trees are then combined for the final prediction44,45. RFR effectively captures nonlinear relationships between input and target variables without making strong assumptions about data distributions, and it is highly robust to noise. In preliminary comparative experiments with other mainstream machine learning methods, RFR demonstrated superior performance in terms of predictive accuracy and computational efficiency—particularly for large-scale, high-resolution datasets46,47. Consequently, RFR was selected as the core modeling method for this study.

The ERA5 parameters functioned as input features, while the corresponding LessRad LWDR data (2002–2022) served as target variables. The dataset underwent random partitioning into training (75%) and testing (25%) subsets, and a ten-fold cross-validation protocol was implemented to optimize key parameters—including the number of decision trees and maximum tree depth—thereby reducing risks of overfitting or underfitting. The calibrated random forest model was then applied to ERA5 data from 1982 to 2001, which were resampled to 0.05° resolution, to generate LWDR predictions at consistent spatial resolution. This methodology effectively extended the temporal coverage of LessRad LWDR from the original 2002–2022 period to a comprehensive 1982–2022 timeframe.

Calculation of LWUR

LWUR is the thermal radiation emitted from the Earth’s surface. It is calculated using GLASS BBE and ERA5 ST according to the equation:

Here, \(\varepsilon \) represents the surface emissivity, σ is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant (5.670374419 × 10−8W ⋅ m−2 ⋅ K−4), \({T}_{s}\) denotes the ST in Kelvin.

Calculation of LWNR

By combining LWDR and LWUR, the LWNR is derived, representing the radiative heat exchange between the surface and the atmosphere. It is calculated using the equation:

A negative LWNR indicates that the surface is losing net longwave energy to the atmosphere, while a positive LWNR signifies net radiation from the atmosphere to the surface. The latter typically occurs under special conditions, such as during nighttime with thick cloud cover, when strong atmospheric back radiation enhances downward longwave flux.

Data accuracy validation

In situ measurements from multiple ground-based observation stations were used to validate the product’s performance across different regions and climate conditions. The evaluation employed key statistical metrics, including the correlation coefficient (R), root mean square error (RMSE), and bias.

Before data matching, all datasets underwent spatial and temporal alignment, as well as rigorous quality control procedures, to ensure comparability and consistency in the validation process.

Here, the observed LWR values at each station are denoted as \({p}_{i}\) (unit: W/m2), and the corresponding predicted values from this dataset at the same spatiotemporal points are represented as \({w}_{i}\). N represents the total number of sample points, while \(\bar{p}\) and \(\bar{w}\,\) denote the mean values of the observed and predicted data, respectively.

Data Records

The dataset is hosted at the National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Data Center (TPDC) and comprises three sub-datasets: LWDR48,49, LWUR50, and LWNR51 (Table 3). All data files are in NETCDF4 format and follow a consistent naming convention. For example, in the filename “LessRad_TYPE_YYYYMMDD_5 km_1 hour_v1.nc”, the components represent data type (“TYPE”), date (“YYYYMMDD”), spatial resolution (“5 km”), temporal resolution (“1 hour”), and version (“v1”). The file “LessRad_LWDR_20020101_5 km_1hour_v1.nc” contains hourly LWDR data (W/m2) for January 1, 2002. Each file includes metadata such as UTC time coordinates (hourly), spatial coordinates (latitude and longitude in WGS84 at 0.05° resolution), quality control flags, and data scaling parameters. The physical values can be obtained using: Y = scale_factor × DN + add_offset, with scale_factor and add_offset stored within the file. Table 4 details the variables and naming conventions. Users can access and visualize the data using software like ArcGIS, Python, or IDL.

Technical Validation

Overall accuracy assessment

Ground-based station observation data were used to validate the accuracy of the LessRad LWDR (a) and LWUR (b) over the entire 41-year period from 1982 to 2022 (Fig. 3). Most data points are concentrated near the 1:1 line. The R values for LWDR and LWUR are 0.94 and 0.97, respectively, indicating strong agreement between the estimated and observed values. The bias values are 4.39 W/m2 for LWDR and 0.14 W/m2 for LWUR, with RMSE values of 24.74 W/m2 and 20.42 W/m2, respectively. These results demonstrate that the LessRad dataset is of high quality and suitable for long-term, fine-scale (0.05°) studies of LWR.

It is worth noting that ground-based stations do not provide direct measurements of LWNR. Deriving LWNR by simply subtracting LWR from LWDR would introduce additional errors, rendering it unsuitable as a reliable reference for validation. Therefore, only the observational validation results for LWDR and LWUR are presented.

Due to differences in LWDR production methodologies, the validation against existing global hourly products was divided into two distinct periods: 1982–2001 and 2002–2022. During 1982–2001, the comparison was limited to LessRad and ERA5, as CERES-SYN data only became available from 2000 onward. To ensure comparability across these periods, all products were uniformly resampled to a common resolution corresponding to their respective validation periods.

As shown in Fig. 4, validation against ground-based observations from 1982 to 2001 reveals that LessRad demonstrates a clear and consistent advantage over ERA5 in estimating LWR. In terms of LWDR, LessRad achieves a notably high R value of approximately 0.96, slightly surpassing ERA5 (0.95). The bias of LessRad is –2.44 W/m2, substantially lower than the –7.33 W/m2 observed for ERA5. Furthermore, LessRad yields a lower RMSE of 24.23 W/m2 compared to 24.79 W/m2 for ERA5. For LWUR, LessRad again outperforms ERA5, attaining a higher R value of 0.97 and a lower RMSE of 22.15 W/m2, relative to the values of ERA5 with 0.96 and 23.85 W/m2, respectively. Although LessRad exhibits a slightly more negative bias (–4.42 W/m2) than ERA5 (–2.59 W/m2), the overall accuracy remains superior.

From 2002 to 2022, a joint analysis was performed on LWDR and LWUR estimates derived from LessRad, ERA5, and CERES-SYN (Fig. 5). For LWDR, LessRad yielded an R value of approximately 0.94, consistent with ERA5 and higher than CERES-SYN’s 0.93. Its RMSE for LWDR was 24.05 W/m2, which is lower than the corresponding RMSEs from the other datasets. The bias of LessRad is 5.10 W/m2, which is lower in absolute terms than –7.28 W/m2 of ERA5, even though CERES-SYN exhibits a smaller underestimation at –0.58 W/m2. Similarly, for LWUR, LessRad achieved an R of about 0.97 and an RMSE of 20.93 W/m2, both indicating improved performance relative to ERA5 and CERES-SYN. In addition, LessRad’s bias stands at 0.82 W/m2, exceeding near-zero –0.14 W/m2 of ERA5, yet it is considerably lower than CERES-SYN’s –1.78 W/m2. Across the entire 41-year dataset, the accuracy of all products remains consistent between the two periods, with LessRad retaining its competitive accuracy advantage.

Spatial and temporal variations

The Tibetan Plateau, with its complex climatic conditions, is recognized as a region highly sensitive to global climate change52. It was selected as the local area to display the spatial distribution of the different products (Fig. 6). Owing to its 0.05° spatial resolution, LessRad displays finer spatial variability compared to ERA5 (0.25°) and CERES-SYN (1°). LWUR shows similar spatial patterns among all products, whereas differences in LWNR distributions are primarily driven by variations in LWDR. The coarser resolution of CERES-SYN results in smoother spatial patterns and less local variability. Previous studies have reported that ERA5 tends to underestimate LWDR over the Tibetan Plateau by more than 20 W/m2 12,13,14, which may contribute to the spatial differences observed across products.

LWR variations across regions were evaluated by comparing RMSE of all products at validation sites during 1982–2001 and 2002–2022 (Fig. 7). Compared to the coarser resolution ERA5 (0.25°) and CERES-SYN (1°), LessRad more accurately characterized radiation features in regions with complex terrain and climate transitions, particularly in polar regions and the Americas.

For LWDR in 1982–2001, LessRad exhibited slightly lower RMSE than ERA5 in North America and Europe. For LWUR during this same period, LessRad demonstrated improved accuracy in North America and Antarctica. Despite limited station coverage, LessRad, with its higher spatial resolution (0.05°), enabled performance comparable to ERA5 in complex terrain.

During 2002–2022 (Fig. 7e–j), the denser site coverage revealed clearer spatial patterns. In polar regions (e.g., Antarctica), both LessRad and ERA5 demonstrated notably lower RMSE for LWDR and LWUR (below 25 W/m2), while the coarser resolution CERES-SYN consistently showed higher errors in these areas. In Asia, all products exhibited relatively high RMSE (typically exceeding 30 W/m2), with CERES-SYN showing the largest errors. For LWUR, the RMSE of LessRad at sites in Antarctica, South and North America was significantly lower than the other two products (mostly below 20 W/m2). Although some stations showed similar performance, LessRad generally achieved lower values.

Based on the calculated global spatial distribution of mean LWR components, Fig. 8 shows that LessRad maintains consistently high correlations with both ERA5 and CERES. This indicates strong agreement in spatial distribution patterns and confirms the reliability of the LessRad product. During the earlier period (1982–2001), the limited availability of satellite observation data led ERA5 to serve as the primary data source for LessRad. Consequently, LessRad exhibits particularly high spatial correlations with ERA5 in LWDR and LWUR, while the correlation in LWNR is comparatively lower. This suggests that, despite the overall strong consistency, LessRad preserves distinct spatial features in the LWR components.

The interannual evolution of performance metrics for LWDR and LWUR from ERA5, CERES-SYN, and LessRad is shown in Fig. 9. Complete annual accuracy metrics are provided in (supplementary Table S1). LessRad consistently demonstrates comparable or higher R values than the other products, exhibiting the highest R values particularly for LWUR.

Annual bias analysis of the products shows differences in the LWDR production modes of LessRad in two periods. During 2002–2022, LessRad consistently shows a positive bias in LWDR, ranging from approximately +2 to +8 W/m2. Before 2001, however, it exhibits a negative bias. A more detailed discussion is provided in the “Inter-Period Bias Discontinuity” section. Despite these differences, the bias remains smaller than that of ERA5, which consistently shows a negative LWDR bias of approximately –10 to –4 W/m2. The LWDR and LWUR biases from CERES-SYN data, which are available from around 2000, are overall closer to zero with minimal variation, possibly due to its relatively coarse spatial resolution (1°). For LWUR, the biases overall are smaller than those for LWDR. The bias magnitude for LessRad is similar to or slightly higher than that of the other products, displaying a slight negative bias in the early years, then gradually trending toward neutrality (with absolute values not exceeding 2 W/m2 after 2002).

In terms of RMSE, the LWDR error levels for the three products remain relatively stable throughout the evaluation period (approximately 23–27 W/m2), although LessRad shows a significantly reduced RMSE during 2010–2016, indicating a clear advantage in accuracy; for LWUR, LessRad exhibits an absolute advantage with RMSE values ranging from approximately 15 to 25 W/m2, whereas CERES shows the highest RMSE and ERA5 falls in between.

The overall bias reported in Fig. 9 represents global average values, while the site-specific biases observed in Fig. 10 help explain the regional variability contributing to these global averages. The reduced bias observed in datasets such as CERES and ERA5 is likely a consequence of spatial smoothing inherent to their coarser resolution. Bias varies considerably across different regions, as illustrated in Fig. 10. Additionally, bias calculation is influenced by site density and the varying data quality of different observational networks. Regions with dense coverage (e.g., North America in Fig. 10e) may disproportionately affect the global bias due to spatial clustering of errors. Considering the regional bias patterns shown in Fig. 10, LessRad generally demonstrates better or comparable bias performance relative to similar products in most cases.

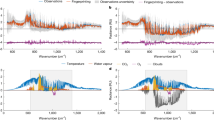

To provide a more detailed evaluation of model performance across different time scales, Fig. 11 presents a daily time series comparison of observed LWDR and LWUR radiation with estimates from LessRad (0.05°), ERA5 (0.25°), and CERES-SYN (1°) at selected sites. The selected years (including 2000, 2001, and 2007) represent the two periods of 1982–2001 and 2002–2022. For LWDR (Fig. 11a,b), all products are capable of capturing both weather-scale and seasonal fluctuations present in the observations. LessRad, with its higher spatial resolution, more accurately reflects rapid changes and reproduces the magnitude of peaks and troughs. Although ERA5 also captures the daily variation fairly well, it exhibits a slight underestimation during certain periods, while the smoother curve generated by the lower-resolution CERES-SYN, although capable of representing seasonal trends, tends to diminish the high-frequency details observed and shows some deviation. For LWUR, which has smaller variations (Fig. 11c,d), all three products display better consistency with the observations and the differences among the products become markedly reduced. The estimates from LessRad and ERA5 are generally closer to the observational curve, accurately reproducing both day-to-day and seasonal variations, whereas the coarse resolution of CERES-SYN results in less notable detail changes and a larger divergence from the other products.

Inter-period bias discontinuity

The LessRad dataset provides high spatiotemporal resolution and demonstrates robust performance across both land and ocean regions. However, a notable limitation is the bias discontinuity between its two major construction periods: 1982–2001 and 2002–2022. As shown in Fig. 9, the LWDR bias shifts from negative values before 2002 to positive values afterward. This shift may influence long-term trend estimation.

This discontinuity results from several interconnected factors involving input data availability, methodological differences, and shifts in external data sources. For the earlier period (1982–2001), previous studies primarily relied on coarse-resolution climate models and reanalysis data. Early satellite observations, such as those from AVHRR, lacked the spectral bands and data quality necessary to support high-accuracy radiation products, thereby imposing certain constraints on LWR estimation53. MODIS, the main source of high-resolution thermal observations for the later period, has provided globally stable products only since early 2000 (Terra) and mid-2002 (Aqua). Consequently, MODIS-derived products and also downstream datasets such as CERES-SYN were only available after that, limiting their utility for constructing earlier long-term records.

Owing to these differences in data availability, the construction approaches for the two periods diverge. As shown in Fig. 2, for 2002–2022, LWDR was derived from MODIS and ERA5, whereas for 1982–2001, it was estimated using a RFR model based solely on ERA5 inputs due to the lack of MODIS data. In addition to methodological differences, the bias inconsistency between the two periods may be attributed to the underlying data sources. Although ERA5 LWDR exhibits relatively consistent biases across the two periods, the development of LessRad also relies on ERA5-derived TCWV and ST. Prior research has identified notable shifts and breaks in these variables around the early 2000s54, which likely contribute to the bias differences in LessRad.

Thus, while LessRad demonstrably outperforms existing products in terms of resolution and accuracy, particularly in complex terrain and under extreme atmospheric conditions, the dataset is not yet homogenized across the full time span. The current version is therefore not recommended for direct use in continuous 41-year trend analysis. However, when analyzed separately, each individual period (1982–2001 and 2002–2022) maintains internal consistency and reliability, and is suitable for studying climate variability and surface radiation characteristics within its respective time window. Users are advised to avoid merging the two periods for long-term climate trend detection without applying appropriate bias adjustment, segmentation, or homogenization techniques.

Features and future work

The present dataset provides global and continuous coverage at a 0.05° spatial resolution and hourly temporal resolution, offering detailed representation of LWR variability across diverse terrain and climatic regions. The 41-year period from 1982 to 2022 enables long-term analyses and supports applications such as climate evaluation and regional forecasting. The validation results support the robustness of the methodology and the reliability of the dataset. As the dataset continues to be maintained and improved, future versions will aim to extend its temporal coverage, enhance consistency between the two periods and across multiple input sources, and improve accuracy by refining the current methods.

Code availability

All the codes used in this study to construct the dataset were written in Python and will be available at https://github.com/yara2017/LessRad-longwvae-Radiation-product.git.

References

Colman, R. A. Climate radiative feedbacks and adjustments at the Earth’s surface. J Geophys Res-Atmos 120, 3173–3182, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014jd022896 (2015).

Wild, M. et al. The global energy balance from a surface perspective. Clim Dynam 40, 3107–3134, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-012-1569-8 (2013).

Shaw, J. K. & Ay, J. K. Processes Controlling the Seasonally Varying Emergence of Forced Arctic Longwave Radiation Changes. J Climate 36, 7337–7354, https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-23-0020.1 (2023).

Wild, M. Decadal changes in radiative fluxes at land and ocean surfaces and their relevance for global warming. Wires Clim Change 7, 91–107, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.372 (2016).

Bourassa, M. A. et al. High-Latitude Ocean and Sea Ice Surface Fluxes: Challenges for Climate Research. B Am Meteorol Soc 94, 403–423, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00244.1 (2013).

Xu, J. et al. A daily 5-km all-sky sea-surface longwave radiation product based on statistically modified deep neural network and spatiotemporal analysis for 1981–2018. Remote Sens Environ 290, 113550, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2023.113550 (2023).

Gelaro, R. et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J Climate 30, 5419–5454, https://doi.org/10.1175/Jcli-D-16-0758.1 (2017).

Kobayashi, S. et al. The JRA-55 Reanalysis: General Specifications and Basic Characteristics. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 93, 5–48, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2015-001 (2015).

Rodell, M. et al. The Global Land Data Assimilation System. B Am Meteorol Soc 85, 381–394, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-85-3-381 (2004).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q J Roy Meteor Soc 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803 (2020).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst Sci Data 13, 4349–4383, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-4349-2021 (2021).

Du, Y. et al. Toward User-Friendly All-Sky Surface Longwave Downward Radiation from Space: General Scheme and Product. B Am Meteorol Soc 105, E1303–E1319, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0126.1 (2024).

Zhu, F. et al. Integration of Multisource Data to Estimate Downward Longwave Radiation Based on Deep Neural Networks. Ieee T Geosci Remote 60, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1109/tgrs.2021.3094321 (2022).

Wang, G., Wang, T. & Xue, H. Validation and comparison of surface shortwave and longwave radiation products over the three poles. Int J Appl Earth Obs 104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2021.102538 (2021).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci Model Dev 9, 1937–1958, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-1937-2016 (2016).

Wild, M. The global energy balance as represented in CMIP6 climate models. Clim Dynam 55, 553–577, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-020-05282-7 (2020).

Zelinka, M. D. et al. Causes of Higher Climate Sensitivity in CMIP6 Models. Geophys Res Lett 47, e2019GL085782, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL085782 (2020).

Xu, J. et al. Assessment of surface downward longwave radiation in CMIP6 with comparison to observations and CMIP5. Atmos Res 270, 106056, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2022.106056 (2022).

Chen, G., Wang, W.-C., Bao, Q. & Li, J. Evaluation of Simulated Cloud Diurnal Variation in CMIP6 Climate Models. J. Geophys. Res. 127, e2021JD036422, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD036422 (2022).

Yang, J., Zhang, Z. Q., Wei, C. Y., Lu, F. & Guo, Q. Introducing the New Generation of Chinese Geostationary Weather Satellites, Fengyun-4. B Am Meteorol Soc 98, 1637–1658, https://doi.org/10.1175/Bams-D-16-0065.1 (2017).

Letu, H. et al. A New Benchmark for Surface Radiation Products over the East Asia-Pacific Region Retrieved from the Himawari-8/AHI Next-Generation Geostationary Satellite. B Am Meteorol Soc 103, E873–E888, https://doi.org/10.1175/Bams-D-20-0148.1 (2022).

Carrer, D. et al. Incoming Solar and Infrared Radiation Derived from METEOSAT: Impact on the Modeled Land Water and Energy Budget over France. J Hydrometeorol 13, 504–520, https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-11-059.1 (2012).

Letu, H. et al. A New Benchmark for Surface Radiation Products over the East Asia-Pacific Region Retrieved from the Himawari-8/AHI Next- Generation Geostationary Satellite. B Am Meteorol Soc 103, E873–E888, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-20-0148.1 (2022).

Platnick, S. et al. The MODIS cloud optical and microphysical products: Collection 6 updates and examples from Terra and Aqua. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens 55, 502–525, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2016.2610522 (2017).

Du, Y. et al. Upscaling of longwave downward radiation from instantaneous to any temporal scale: Algorithms, validation, and comparison. Int J Appl Earth Obs 117, 103196, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2023.103196 (2023).

Liang, S. L. et al. The Global Land Surface Satellite (GLASS) Product Suite. B Am Meteorol Soc 102, E323–E337, https://doi.org/10.1175/Bams-D-18-0341.1 (2021).

Zeng, Q., Cheng, J. & Guo, M. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Three Global Surface Longwave Radiation Products. Remote Sens-Basel 15, 2955 (2023).

Wang, K. C. & Dickinson, R. E. Global atmospheric downward longwave radiation at the surface from ground-based observations, satellite retrievals, and reanalyses. Rev Geophys 51, 150–185, https://doi.org/10.1002/rog.20009 (2013).

Ma, Q., Wang, K. C. & Wild, M. Evaluations of atmospheric downward longwave radiation from 44 coupled general circulation models of CMIP5. J Geophys Res-Atmos 119, 4486–4497, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013jd021427 (2014).

Gui, S., Liang, S. L. & Li, L. Evaluation of satellite-estimated surface longwave radiation using ground-based observations. J Geophys Res-Atmos 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009jd013635 (2010).

Liang, S., Wang, K., Zhang, X. & Wild, M. Review on Estimation of Land Surface Radiation and Energy Budgets From Ground Measurement, Remote Sensing and Model Simulations. Ieee J-Stars 3, 225–240, https://doi.org/10.1109/jstars.2010.2048556 (2010).

Wang, T. X. et al. Improved Algorithm to Derive All-Sky Longwave Downward Radiation From Space: Application to Fengyun-4A Measurements. Ieee T Geosci Remote 61, https://doi.org/10.1109/Tgrs.2023.3297859 (2023).

Cheng, J., Liang, S., Verhoef, W., Shi, L. & Liu, Q. Estimating the Hemispherical Broadband Longwave Emissivity of Global Vegetated Surfaces Using a Radiative Transfer Model. Ieee T Geosci Remote 54, 905–917, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2015.2469535 (2016).

Cheng, J. & Liang, S. Estimating the broadband longwave emissivity of global bare soil from the MODIS shortwave albedo product. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 614–634, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JD020689 (2014).

Driemel, A. et al. Baseline Surface Radiation Network (BSRN): structure and data description (1992–2017). Earth Syst Sci Data 10, 1491–1501, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-10-1491-2018 (2018).

Mangum, L. J., Freitag, H. P. & McPhaden, M. J. TOGA-TAO array sampling schemes and sensor evaluations. Proceedings of OCEANS’94 2, II/402–II/406, https://doi.org/10.1109/OCEANS.1994.364077 (1994).

Schmidt, A., Hanson, C., Chan, W. S. & Law, B. E. Empirical assessment of uncertainties of meteorological parameters and turbulent fluxes in the AmeriFlux network. J Geophys Res-Biogeo 117, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012jg002100 (2012).

Tamagawa, K. et al. An Advanced Quality Control System for the CEOP/CAMP In-Situ Data Management. Ieee Syst J 2, 406–413, https://doi.org/10.1109/Jsyst.2008.927710 (2008).

Mizoguchi, Y., Miyata, A., Ohtani, Y., Hirata, R. & Yuta, S. A review of tower flux observation sites in Asia. J Forest Res-Jpn 14, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10310-008-0101-9 (2009).

Ma, Y. et al. A long-term (2005–2016) dataset of hourly integrated land–atmosphere interaction observations on the Tibetan Plateau. Earth Syst Sci Data 12, 2937–2957, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-2937-2020 (2020).

Wang, T. et al. Improved Algorithm to Derive All-Sky Longwave Downward Radiation From Space: Application to Fengyun-4A Measurements. Ieee T Geosci Remote 61, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2023.3289058 (2023).

Du, Y. et al. Upscaling of longwave downward radiation from instantaneous to any temporal scale: Algorithms, validation, and comparison. Int J Appl Earth Obs 117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2023.103196 (2023).

Wang, S., Wang, T., Du, Y., Wang, S. & Li, S. A Method to Derive Long-Term Global Hourly Near-Surface Air Temperature by Combining Remote Sensing and Reanalysis Datasets. Ieee Geosci Remote S 22, 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2025.3554488 (2025).

Belgiu, M. & Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. Isprs J Photogramm 114, 24–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2016.01.011 (2016).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learning 45, 5–32, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Feng, C. J. et al. Estimating Surface Downward Longwave Radiation Using Machine Learning Methods. Atmosphere-Basel 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11111147 (2020).

Feng, Y. et al. Evaluation of temperature-based machine learning and empirical models for predicting daily global solar radiation. Energy Conversion and Management 198, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.111780 (2019).

Du Yihan, W. S. W. T. LessRad Global Surface Longwave Downward Radiation Dataset (5 km, hourly, 1982–2001). National Tibetan Plateau Data Center https://doi.org/10.11888/Terre.tpdc.302279 (2025).

Du Yihan, W. T. LessRad Global Surface Longwave Downward Radiation Dataset (5 km, hourly, 2002–2022). National Tibetan Plateau Data Center https://doi.org/10.11888/Terre.tpdc.300867 (2024).

Du Yihan, W. S. W. T. LessRad Global Surface Longwave Upward Radiation Dataset (5 km, hourly, 1982–2022). National Tibetan Plateau Data Center https://doi.org/10.11888/Terre.tpdc.302277 (2025).

Du Yihan, W. S. W. T. LessRad Global Surface Longwave Net Radiation Dataset (5 km, hourly, 1982–2022). National Tibetan Plateau Data Center https://doi.org/10.11888/Terre.tpdc.302406 (2025).

Hu, S. Z. et al. Mechanisms of Tibetan Plateau Warming Amplification in Recent Decades and Future Projections. J Climate 36, 5775–5792, https://doi.org/10.1175/Jcli-D-22-0471.1 (2023).

Karlsson, K. G. et al. CLARA-A3: The third edition of the AVHRR-based CM SAF climate data record on clouds, radiation and surface albedo covering the period 1979 to 2023. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 4901–4926, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-4901-2023 (2023).

Wan, N. H., Lin, X. M., Pielke, R. S. R., Zeng, X. B. & Nelson, A. M. Global total precipitable water variations and trends over the period 1958-2021. Hydrol Earth Syst Sc 28, 2123–2137, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-28-2123-2024 (2024).

Loeb, N. G. et al. Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System (CERES) Energy Balanced and Filled (EBAF) Top-of-Atmosphere (TOA) Edition-4.0 Data Product. J Climate 31, 895–918, https://doi.org/10.1175/Jcli-D-17-0208.1 (2018).

Rutan, D. A. et al. CERES Synoptic Product: Methodology and Validation of Surface Radiant Flux. J Atmos Ocean Tech 32, 1121–1143, https://doi.org/10.1175/Jtech-D-14-00165.1 (2015).

NASA/LARC/SD/ASDC. GEWEX SRB Integrated Product (Rel-4) Longwave 3-Hourly Monthly Average by UTC Land-only Fluxes. NASA Langley Atmospheric Science Data Center DAAC, https://doi.org/10.5067/GEWEXSRB/Rel4IP_Longwave_3hrlymonthly_landonly_utc_1.

Zhang, Y. & Rossow, W. B. Global Radiative Flux Profile Data Set: Revised and Extended. J. Geophys. Res. 128, e2022JD037340, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JD037340 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China project [grant numbers. 42371342, 42022008]; the Innovation Group Project of Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) [grant numbers. 311021003]; the China Scholarship Council program [grant numbers. 202406380263]; The author extends sincere gratitude to the Meteorological Institute, Center for Earth System Research and Sustainability (CEN), University of Hamburg for their invaluable support and resources provided during the author’s visit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yihan Du and Tianxing Wang conceived and designed this study; Yihan Du and Shuo Wang wrote the codes used to construct the dataset, performed data validation and drafted the manuscript; Tianxing Wang provided guidance and revised the manuscript; Yuyang Xian contributed to manuscript revision and provided valuable comments; All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, Y., Wang, S., Wang, T. et al. A 41-Year Global All-Sky Surface Longwave Radiation Components Dataset at 5 km and hourly Resolution. Sci Data 12, 1540 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05886-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05886-w