Abstract

Rivers are dynamic ecosystems that play a crucial role in supporting microbial diversity and sustaining a wide range of ecological functions. Here, we used metagenomic sequencing datasets of channel sediments, riparian bulk soils, and riparian rhizosphere soils to construct metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from 30 river wetlands along a latitudinal gradient in China. We identified 236 MAGs with completeness ≥ 50% and contamination ≤ 10%, including 225 bacteria and 11 archaea. Among these, 24.2% showed a completeness of 80% or higher. The dominant taxa were assigned to Pseudomonadota (78 MAGs), Actinomycetota (47 MAGs), and Bacteroidota (29 MAGs), which were particularly prevalent in riparian soils. These draft genomes provide valuable insights into microbial diversity and biogeochemical potential in river wetlands, enhancing our understanding of how microorganisms have evolved to adapt to the complex environments of rivers and latitudinal variation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Latitude determines microbial species migration, distribution, and ecological function through climatic and geographic variation1,2,3. In recent years, the relationships between various microbial taxa and latitudinal gradients have been investigated in numerous regions by amplicon sequencing4,5,6. However, as amplicon sequencing targets only one or a few gene regions, it often fails to provide knowledge of the overall microbial diversity. In contrast, metagenomics provides abundant information about microbial genes, allowing us to gain a deeper understanding of microbial distribution patterns and functional potentials7,8,9. Despite this advantage, large-scale investigations of microbial diversity along latitudinal gradients using metagenomic approaches remain scarce. Understanding how microbial communities respond to environmental changes along latitudinal gradients is critical for comprehending ecosystem functions and assessing microbial adaptation to climate variation.

Rivers play a crucial role in supporting biodiversity and providing a wide range of ecosystem services10,11. Due to the complex hydrological environments, river ecosystems harbor highly diverse microbial communities12. Despite numerous studies investigating microbial diversity in specific rivers using metagenomics9,13,14,15,16, a notable gap remains in large-scale observational studies, particularly those along latitudinal gradients. With the expansion of urbanization and agriculture, river flow regimes and water quality are increasingly impacted and degraded17. However, the metabolic activities of river microbiomes can mitigate these impacts by influencing river water purification, greenhouse gas emissions, nitrogen cycling, and food webs18,19,20. Given that microbes are critical regulators of ecological processes and functions, a deeper assessment of their ecological and biogeochemical contributions across diverse river systems is urgently needed. Therefore, further research is necessary to clarify the distribution patterns of microbial communities in various rivers, elucidating their ecological roles and responses to anthropogenic perturbations.

Here, we present 236 metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) reconstructed from channel sediments, riparian bulk soils (at two depths: 0–20 and 40–60 cm), and riparian rhizosphere soils collected from 30 river wetlands (e.g., the Yangtze River and Yellow River) along a latitudinal gradient in China (Table 1; Fig. 1a). All MAGs met the quality thresholds of ≥50% completeness and ≤10% contamination, in accordance with the standard Medium-quality MAGs metrics21. Of these, 48.3% (114 MAGs) exhibited >70% completeness, and 8.1% (19 MAGs) were classified as “near complete” with >90% completeness and <5% contamination. Additionally, 65.7% (155 MAGs) had low contamination (<5%), and 3.8% (9 MAGs) had no contamination (Table S1). Genome sizes, estimated using CheckM v1.0.1222, ranged from 0.50 Mbp to 8.19 Mbp, with an average value of 2.61 Mbp (Table S1).

These draft genomes were classified as 225 bacteria and 11 archaea based on the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB)23 (Fig. 1b). For bacteria, approximately 19 phyla were identified, with the majority belonging to the phyla Pseudomonadota (34.67%), Actinomycetota (20.89%), and Bacteroidota (12.89%). However, only 20% (45 MAGs) could be assigned to currently known taxa at the species level, while 80% (180 MAGs) represent potentially novel taxa (Fig. 2a; Table S2). No significant correlation was observed between contamination and completeness, or between genome size and N50 length, although species-level bacterial MAGs whose completeness was < 80% tended to exhibit higher contamination (Fig. 2c,e). For archaea, the 11 MAGs were classified into the phyla Halobacteriota (18.18%) and Thermoproteota (81.82%), with approximately 90.91% representing novel taxa (Fig. 2b; Table S2). Similarly, no significant correlations were detected between contamination and completeness, or between genome size and N50 length among archaeal MAGs (Fig. 2d,f).

Overview of the MAGs. Number and distribution of all species-level bacterial (a) and archaeal (b) MAGs at the phylum level. Relationship between N50 length and genome size for species-level bacterial (c) and archaeal (d) MAGs. Relationship between contamination and completeness for species-level bacterial (e) and archaeal (f) MAGs.

Methods

Sampling

In September 2018, channel sediments, riparian bulk soils, and riparian rhizosphere soils were collected from 30 river wetlands along an approximately 3500 km latitudinal transect in eastern China (Fig. 1a). For each wetland, a representative sampling site was established in areas where the riparian wetlands had flat topography and formed relatively wide bands (>10 m). Approximately 200 g of surface channel sediments (0–20 cm) were collected at three random points, 5–10 m from the shore, using a homemade grab sampler. Riparian bulk soils (0–20 and 40–60 cm) were obtained from bare areas using a soil drilling machine (SSD, Zhonghe Technology, Beijing, China). To collect riparian rhizosphere soils, a 1 × 1 m plot was established within a representative plant community at each sampling site. Then, the most dominant plant species within the plot were carefully excavated to a depth of approximately 20 cm, and rhizosphere soil was collected using a sterilized soft brush after gently shaking off loosely attached soils from the plant roots. More detailed information about these river wetlands and sampling methodology has been previously described4.

DNA extraction and metagenomic sequencing

For all soil and sediment samples, DNA was extracted using the PowerSoil® DNA Isolation Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (MoBio, Carlsbad, California, USA). DNA quantity was measured using the ExKubit dsDNA HS test kit (ExCell Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) with a Qubit fluorimeter (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All high-quality DNA extracts were subsequently sent for metagenomic sequencing.

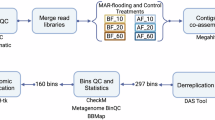

Metagenomic sequencing libraries were prepared using the TrueLib DNA Library Rapid Prep Kit for Illumina (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Index codes were added into the attribute sequences of each sample for differentiation during sequencing. Sequencing was conducted on the Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 System (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), using a paired-end sequencing approach with read lengths of 2 × 150 bp (total size 350 bp). Adapter sequences were removed from the raw reads. The low-quality reads, containing quality values ≤ 10 exceeding 50% of the read length, and the content of N base up to 10% of the read length, were filtered by using fastp v0.23.2 (parameters: default)24. The high-quality reads from each river wetland were co-assembled using MEGAHIT v1.2.9 (parameters: default)25. The quality of the assembled contigs was evaluated with CheckM v1.0.1222 to ensure the integrity and completeness of the assembly.

Genome binning, refinement, and dereplication

The MetaWRAP v1.3.221 pipeline, integrating MaxBin2 v2.2.6 and metaBAT2 v2.112.1 metagenomic binning software, was used to recover genome bins based on tetranucleotide frequencies, GC content, and coverage26. The MetaWRAP-Bin_refinement module (parameters: -c 50 × 10) was applied to refine the initial binning results, which originally included 3547 bins, resulting in 260 refined bins. The contamination and completeness of all bins were estimated by a lineage-specific work flow in CheckM. The refined bins were dereplicated using dRep v2.6.225 (parameters: -sa 0.95 -nc 0.30 -comp 50 -con 10) at 95% average nucleotide identity (ANI). This process led to the identification of 236 unreplicated species-level MAGs. Taxonomic classification of the MAGs was conducted using the classify_wf workflow in GTDB-TK v2.0.0, based on GTDB release 21427.

Data Records

The raw sequence data are available on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) associated with BioProject number PRJNA77983228 and accession number SRP34607929. The environmental metadata for sample sites, along with the fasta sequences, genome annotation, and relative abundance information for 225 species-level bacterial MAGs and 11 species-level archaeal MAGs, are publicly available on Figshare30.

Technical Validation

To prevent sample contamination, all sampling tools and containers, including a homemade grab sampler, soil drilling machine, soft brushes, and plastic centrifuge tubes, were thoroughly sterilized prior to fieldwork. To preserve DNA integrity, collected samples were immediately stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. Genome completeness and contamination were assessed using CheckM, and only MAGs with ≥50% completeness and ≤10% contamination were included in the final analysis. Additionally, to further reduce contamination and improve completeness, MetaWRAP was employed to reassemble and refine the genome bins.

Code availability

Custom scripts were not used to generate or process this dataset. Software versions and non-default parameters used have been appropriately specified where required.

References

Jablonski, D., Roy, K. & Valentine, J. W. Out of the Tropics: Evolutionary dynamics of the latitudinal diversity gradient. Science 314, 102–6 (2006).

Mittelbach, G. G. et al. Evolution and the latitudinal diversity gradient: speciation, extinction and biogeography. Ecol Lett 10, 315–31 (2007).

Bahram, M. et al. Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome. Nature 560, 233–237 (2018).

Xiong, X. et al. Species pool and local assembly processes drive β diversity of ammonia-oxidizing and denitrifying microbial communities in rivers along a latitudinal gradient. Mol Ecol 33, e17516 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Local community assembly mechanisms shape soil bacterial β diversity patterns along a latitudinal gradient. Nat Commun 11, 5428 (2020).

Xiao, X. et al. A latitudinal gradient of microbial β‐diversity in continental paddy soils. Global Ecol Biogeogr 30, 909–919 (2021).

Nishimura, Y. & Yoshizawa, S. The OceanDNA MAG catalog contains over 50,000 prokaryotic genomes originated from various marine environments. Sci. Data 9, 305 (2022).

Wang, J. & Jia, H. Metagenome-wide association studies: fine-mining the microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 508–522 (2016).

Deng, D. et al. Metagenomic insights into nitrogen-cycling microbial communities and their relationships with nitrogen removal potential in the Yangtze River. Water Res 265, 122229 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Seasonal variations and hydrological management regulate nutrient transport in cascade damming: Insights from carbon and nitrogen isotopes. Water Res 271, 122894 (2025).

Deng, D., He, G., Yang, Z., Xiong, X. & Liu, W. Activity and community structure of nitrifiers and denitrifiers in nitrogen-polluted rivers along a latitudinal gradient. Water Res 254, 121317 (2024).

Wan, W. et al. Beyond biogeographic patterns: Processes shaping the microbial landscape in soils and sediments along the Yangtze River. mLife 2, 89–100 (2023).

Gao, F. Z. et al. Unveiling the overlooked small-sized microbiome in river ecosystems. Water Res 265, 122302 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals the response of microbial community in river sediment to accidental antimony contamination. Sci Total Environ 813, 152484 (2022).

Zhang, S. Y. et al. Intensive allochthonous inputs along the Ganges River and their effect on microbial community composition and dynamics. Environ Microbiol 21, 182–196 (2019).

Borton, M. A. et al. A functional microbiome catalogue crowdsourced from North American rivers. Nature 637, 103–112 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. The plastic age: river pollution in china from crop production and urbanization. Environ Sci Technol 57, 12019–12032 (2023).

Battin, T. J. et al. River ecosystem metabolism and carbon biogeochemistry in a changing world. Nature 613, 449–459 (2023).

Rodríguez-Ramos, J. A. et al. Genome-resolved metaproteomics decodes the microbial and viral contributions to coupled carbon and nitrogen cycling in river sediments. mSystems 7, e0051622 (2020).

Boddicker, A. M. & Mosier, A. C. Genomic profiling of four cultivated Candidatus Nitrotoga spp. predicts broad metabolic potential and environmental distribution. ISME J 12, 2864–2882 (2018).

Bowers, R. M. et al. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat Biotechnol 35, 725–731 (2017).

Parks, D. H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C. T., Hugenholtz, P. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Parks, D. H. et al. GTDB: an ongoing census of bacterial and archaeal diversity through a phylogenetically consistent, rank normalized and complete genome-based taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res 50, D785–D794 (2022).

Jiang, C. et al. Frequency of occurrence and habitat selection shape the spatial variation in the antibiotic resistome in riverine ecosystems in eastern China. Environ Microbiome 17, 53 (2022).

Li, D. H., Liu, C. M., Luo, R. B., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T. W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31, 1674–1676 (2015).

Xue, Z., Han, Y., Tian, W. & Zhang, W. Metagenome sequencing and 103 microbial genomes from ballast water and sediments. Sci. Data 10, 536 (2023).

Chaumeil, P. A., Mussig, A. J., Hugenholtz, P. & Parks, D. H. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics 36, 1925–1927 (2020).

NCBI BioProject https://identifiers.org/ncbi/bioproject:PRJNA779832 (2023).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP346079 (2023).

Xiong, X. 236 metagenome-assembled microbial genomes in 30 rivers along a latitudinal gradient. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28648673.v3 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Wen Zhou, Bei Lu, Yongtai Pan, Jian Ouyang, Danli Deng, Xiaoyan Liu, and Lu Ouyang for their assistance with the field work and laboratory analyses. This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24A20641 and 32401363), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2025AFB983), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M733714).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.X. and S.L. performed the data analysis. J.H. and L.F. collected samples and extracted DNA for the Illumina sequencing. W.L. conceptualized and designed the study. X.X. and W.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, X., Liu, S., Huang, J. et al. 236 metagenome-assembled microbial genomes from rivers along a latitudinal gradient. Sci Data 12, 1516 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05888-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05888-8