Abstract

Eocanthecona furcellata (Wolff, 1811) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae: Asopinae), a predatory stinkbug, preys on diverse notorious insect pests, positioning it as a critical biocontrol agent in agricultural and forestry ecosystems with substantial regional application and promotion potential. We present a chromosome-level genome assembly of E. furcellata using PacBio HiFi long-read sequencing and Hi-C scaffolding technologies. The final genome spans 1.03 Gb, with a contig N50 of 2.35 Mb and a scaffold N50 of 135.69 Mb, achieving 97.0% BUSCO completeness with the Hemiptera_odb10 lineage dataset. Hi-C data resolved the assembly into 7 pseudochromosomes, representing the full karyotype. Repeat elements constitute 52.07% of the genome (approximately 520.07 Mb). We annotated 15,802 protein-coding genes, of which 90.72% were informatively assigned. This high-quality genome provides a foundational resource for advancing research on predatory bug biology, including genetic adaptations for digestion, molecular mechanisms of prey detection, and biocontrol optimization through functional genomics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

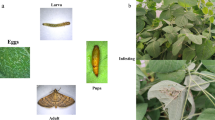

In agroecosystems, predatory stinkbugs of the subfamily Asopinae (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) play a vital role in pest management1. Eocanthecona furcellata (Wolff, 1811), formerly Canthecona furcellata, is a key species within this group, renowned for its high fecundity and formidable predatory abilities. These traits enable E. furcellata to effectively suppress a broad range of pests, including Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Diptera, and phytophagous Pentatomidae species2,3. The insect is widely distributed across Southeast Asia, inhabiting southern China, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Myanmar, Indonesia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka4. As a paurometabolous insect, E. furcellata undergoes 3 developmental stages (egg, nymph, and adult), with the nymphal stage comprising 5 distinct instars (Fig. 1)4. In addition, E. furcellata employs extraoral digestion to process large prey, extracting nutrients through refluxing and non-refluxing mechanisms while injecting hydrolytic enzymes into the prey, a process analogous to that observed in Arma chinensis Fallou5,6. To optimize E. furcellata’s role as a biocontrol agent, researchers have expanded studies beyond morphological trait observation, focusing on phylogenetic relationships4,7, functional characterization of pheromones and pheromone receptors8,9, and diapause/dormancy mechanisms10,11. Studies have also highlighted its potential for combined application with nucleopolyhedrovirus (NPV)12,13,14. Notably, E. furcellata exhibits high tolerance to sub-lethal concentrations LC30 of insecticides such as chlorpyrifos15 and λ-cyhalothrin16,17. Intriguingly, sub-lethal LC30 concentrations of chlorpyrifos can enhance its predatory efficiency and maximum predation capacity15. Despite these insights, the absence of a high-quality genome for E. furcellata has severely limited deeper investigations into its gene functions. Thus, assembling a high-quality genome for this species is critical not only for advancing E. furcellata researches but also for understanding its closely related species.

Thus, we employed a combined strategy of PacBio long-read HiFi and Hi-C sequencing, to assembled a high-quality chromosome-level reference genome for E. furcellata. Based on the previously reported karyotype of E. furcellata2, we employed a hybrid sequencing strategy combining PacBio HiFi long-reads and Hi-C scaffolding to assemble a high-quality, chromosome-level genome for E. furcellata. The final assembly spans 1.03 gigabases (Gb), with a contig N50 of 2.35 megabases (Mb) and a scaffold N50 of 135.69 Mb. Hi-C scaffolding resolved the genome into seven pseudochromosomes, consistent with prior karyotype studies of E. furcellata2. Repetitive elements constituted 52.07% (520.07 Mb) of the genome, and 15,802 protein-coding genes were predicted evidenced by transcripts from different organ or developmental stages of the stinkbugs, in which 90.72% functionally annotated based on different database. This high-quality genome provides a critical resource for advancing evolutionary, ecological, and biocontrol research within the Asopinae subfamily.

Methods

Insect rearing and sample collection

Male and female individuals of E. furcellata were collected from a wild population in Nanhua, Chuxiong City, Yunnan Province, China (25° 17′ N, 101° 23′ E), and reared in our laboratory for over 30 generations. The insects were fed Tenebrio molitor larvae under controlled environmental conditions: 29 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 5% relative humidity, and a 16-hour light/8-hour dark photoperiod. To minimize genetic variation, we sequenced the genome of female offspring from four consecutive generations of inbreeding. Prior to sequencing, insect surfaces were sterilized with 75% ethanol. Whole genomic DNA extracted from female adults was used for genome sequencing and assembly.

DNA and RNA sequencing

The genomic DNA, which was prepared using the Insect DNA Extraction Kit (Genenode, Beijing, China), was assessed for integrity and contamination via agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified using a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). A short-read DNA sequencing library was constructed with the VAHTS™ Universal DNA Library Prep Kit for MGI (Vazyme, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Three distinct sequencing data types, DNBSEQ short reads, PacBio HiFi reads, and Hi-C short reads, were generated and used for genome assembly. For short-read sequencing, paired-end libraries (2 × 150 bp) with ~ 350 bp insert sizes were prepared and sequenced on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform (BGI, Shenzhen, China). For PacBio long-read sequencing, genomic DNA (~8 μg) was sheared using g-TUBEs (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA) and concentrated with AMPure PB magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). SMRTbell libraries were prepared using the Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Bell Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA), size-selected on a BluePippin™ system (Sage Science, Beverly, MA, USA) with a ≥ 15 kb cutoff, and sequenced on the PacBio Sequel II platform in circular consensus sequencing (CCS) mode. For Hi-C library preparation, whole adult insects were crosslinked with 2% formaldehyde, and chromatin was digested with the MboI restriction enzyme (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Hi-C libraries, with ~ 350 bp inserting size, were sequenced on the DNBSEQ platform to generate 150 bp paired-end reads. For transcriptomic analysis, RNA was extracted from whole insects or tissues with Insect RNA column Extraction Kit. Transcriptome libraries were prepared using the TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit v2 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with polyA selection and insert sizes of 200–400 bp. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), yielding 150 bp paired-end reads.

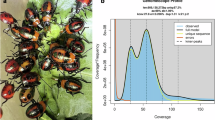

K-mer analysis for genome size estimation

A total of 63.91 Gb of short read data, underwent quality control and filtering using fastQC (v0.11.3) and fastp (v0.23.2)18, respectively, to obtain clean data. Subsequently, 10,000 pairs of reads are randomly selected and aligned against the NCBI nucleotide database (NT database) using Blastn (v2.11.0+, -evalue 0.00001)19, which resulted in the top 80% of matched species being displayed (Supplementary Table 1). Based on the NT alignment results, the sequenced data shows no significant foreign contamination. The software Jellyfish (v2.3.0, -m 21 -s 1000000000)20 was used to generate K-mer frequency distribution information. GenomeScope (v2.0, -k 21 -p 2)21 was then employed to estimate genome heterozygosity, repeat content, and genome size based on the resulted K-mer frequency distribution. The results indicated the estimated maximum genome size is 1,015 Mb, with a heterozygosity rate of 1.49% and a repeat sequence proportion of 32.46% (Fig. 2A). Additionally, Smudgeplot (v0.2.3dev, -k 21 -n 24 –m 160 –ci 1 –cs 10000)21 was used to estimate the ploidy of E. furcellata, and the results showed that the AA type accounted for the highest proportion, suggesting that the species is most likely diploid (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Table 2).

Result of Survey. (A) K-mer (k = 21) depth and K-mer (k = 21) type frequency distribution plot. The horizontal axis represents the Kmer depth, while the vertical axis represents the corresponding number of Kmers at each depth. (B) Smudgeplots K-mer statistical distribution plot. The x-axis represents relative coverage (CovB / (CovA + CovB)), the y-axis shows total coverage (CovA + CovB), and the color indicates the frequency of k-mer pairs. Each haplotype structure appears as a “smudge” on the plot, where the heat intensity of the smudge reflects the occurrence frequency of that haplotype structure in the genome.

Genome assembly and contigs anchoring

Single Molecule Real-Time sequencing (SMRT) technology was used to generate a total of 33.5 Gb of HiFi data. The genome was assembled using HiFiasm22 was used for assembly, and the purge_haplotigs23 was employed to remove redundancy from the initially assembled and error-corrected genome. The resulting draft genome was further polished using short-read data with Pilon (v1.24)24 and long-read HiFi data with Racon (v1.4.21)25, respectively, resulting in a polished genome length of 1,126,600,320 bp, with an N50 of 2,349,459 bp, a GC content of 32.04% and a longest contig of 12,258,061 bp. The overall quality of the polished genome was evaluated using BUSCO (v5.4.3; -l hemiptera_odb10)26 revealed 97.0% completeness of conserved hemipteran genes. Alignment of long-read data to the assembled genome yielded a 99.86% mapping rate and 99.92% coverage, while short-read data alignment achieved a 98.60% mapping rate and 99.36% coverage (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

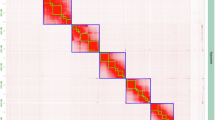

For scaffolding the contigs into chromosomes, a total of 128.5 Gb of Hi-C reads were generated and aligned to the genome using Bowtie2 (v2.5.1)27 to determine the orientation of primary contigs on the chromosomes. Based on the principle that cis-interactions (interactions within the same chromosome) are significantly stronger than trans-interactions (interactions between different chromosomes), and that interaction strength decreases with increasing linear distance within cis-interactions, the contigs were segmented, anchored, ordered, oriented, and merged to assemble a chromosome-level genome with ALLHiC (v0.9.14)28. Subsequently, JuiceBox (v1.11.08)29 was employed for visualization and manual error correction. During genome scaffolding, the original 934 contigs were split based on the interaction map, reordered, and ultimately assembled into 7 chromosomes (consistent with prior karyotype analysis findings2) and 122 unanchored scaffolds, yielding a total genome length of 1.03 Gb. The contig N50 was 2.19 Mb, and the scaffold N50 reached 135.69 Mb, with a chromosome anchoring rate of 95.38%. In addition, BUSCO results showed that it had 98.1% completeness. (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 3).

Genome annotation and assessment

Both homology-based and de novo methods were applied for repetitive sequence annotation. Homology-based prediction was conducted using RepeatMasker (v4.0.9) and its internal RepeatProteinMask tool30, leveraging the RepBase database (v21.12, http://www.girinst.org/repbase) of known repetitive sequences. A custom repeat library was then constructed using RepeatModeler (v1.0.11)31 and LTR_FINDER_parallel (v1.0.7)32, which was then integrated with RepeatMasker for de novo prediction of repetitive sequences. For the de novo approach, repetitive sequences were first identified by de novo prediction based on sequence alignment features and transposable element structures, followed by refinement and validation using RepeatMasker. And tandem repeats were predicted using Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF, v4.09)33. Additionally, Extensive de novo TE Annotator (EDTA, v2.2.2) was further employed to evaluate the repetitive sequences.

Gene structure prediction integrated three approaches included (1) RNA-seq-guided annotation: RNA-seq data from multiple developmental stages were aligned to the genome using HISAT2 (v2.1.0)34, and transcripts were assembled with StringTie (v1.3.5)35; (2) Homology-based prediction: Protein sequences from related species (e.g., Nezara viridula36, and Nesidiocoris tenuis37,38) were mapped to the genome using Liftoff (v1.6.3)39 and structurally intact genes were retained to train the AUGUSTUS (v3.5.0) gene model40; and (3) De novo prediction was performed using AUGUSTUS in self-training optimization mode combined with a phylogenetically-informed conserved gene database. The final gene set was generated by integrating repetitive sequences, transcriptomes, and homology-based predictions using Maker (v3.01.03)41 with default parameters.

Two approaches were implemented for functional annotation of the protein-coding gene set: (1) sequence similarity-based analysis using diamond (v2.0.14, -- evalue 1e-05)42 to align protein sequences against databased including SwissPro (https://www.expasy.org/resources/uniprotkb-swiss-prot), NCBI nucleotide sequence database (NT) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/), NCBI non-redundant databases (NR) (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/db/FASTA/nr.gz), Pfam (http://xfam.org/), EggNOG (http://eggnogdb.embl.de/), Gene Ontology (GO) (http://geneontology.org/page/go-database), and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) databases for functional and pathway annotation, and (2) domain/motif-based analysis employing InterProScan (v5.61–93.0) to query InterPro sub-databases for conserved sequences/motifs/domains, supplemented by HMMER3 (v3.3.1)43 for HMM-based annotation of transcription factors and Pfam domains. A total of 14,336 genes (accounting for 90.72% of all protein-coding genes) were functionally annotated (including 1,168 unnamed, uncharacterised, and hypothetical genes, accounting for 8.14%), while 1,466 genes (9.28%) remained unannotated (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 4–6, Supplementary Figs. 2–4).

Genome mapping of the E. furcellata. In this figure, circle (a) means GC content distribution; circle (b) means genomic information; circle (c) means repeat sequence distribution; circle (d) means LTR distribution; circle (e) means LINE distribution; and circle (f) means DNA-TE distribution. And the darker colors within the rings indicate more concentrated distribution of the elements.

Data Records

The chromosomal-level genome assembly data have been deposited in GenBank with the accession number JBPZNH00000000044. Additionally, the genome annotation files have been deposited Figshare45. The NGS, HiFi and HiC sequencing data have been deposited in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) under accession number CRA01391246, as well as the transcriptome data showed in the NGDC under accession number CRA02556847.

Technical Validation

Genome assembly accuracy was assessed by aligning clean short reads to the assembled genome using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA, v0.7.18)48, achieving a 98.30% mapping rate and 99.82% genome coverage, confirming high assembly continuity. Genome completeness was evaluated using two complementary approaches: BUSCO analysis (v5.4.3) with the Hemiptera_odb10 lineage dataset identified 97.0% complete genes (94.5% single-copy, 2.5% duplicated) and only 0.3% fragmented genes based on the protein-coding genes (Supplementary Table 6). LTR Assembly Index (LAI) assessment using LTR_Retriever (v2.9.0)49 yielded a score of 8.46, reflecting relative repetitive region integrity. These results collectively demonstrate the genome’s high continuity, accuracy, and completeness, establishing it as a reference-grade genome.

Data availability

This study utilized two publicly available datasets, which can be accessed from NCBI under accession numbers related to N. viridula36 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_928085145.1) and N. tenuis37 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_902806785.1). All experimentally determined data generated in this study are available: The chromosomal-level genome assembly data are available at GenBank44 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/JBPZNH000000000.1); the genome annotation files are available at Figshare45 (https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/_b_i_Eocanthecona_furcellata_i_b_genome_data/29512190); the NGS, HiFi and HiC sequencing data as well as the transcriptome data are available at NGDC46,47 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA013912 and https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA025568, respectively).

Code availability

No custom codes were used in this study. All bioinformatics tools and software applications were used according to their respective manuals and protocols. The specific software versions and parameters used are detailed in the Methods section.

References

Memmott, J., Martinez, N. D. & Cohen, J. E. Predators, parasitoids and pathogens: species richness, trophic generality and body sizes in a natural food web. J. Anim. Ecol. 69, 1–15 (2000).

Kaur, H. & Semahagn, B. K. Meiotic behaviour of chromosomes in three predator species of the subfamily Asopinae (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Comp. Cytogenet. 4, 133–139 (2010).

Yasuda, T. & Wakamura, S. Rearing of the predatory stink bug, Eocanthecona furcellata (Wolff) (Heteroptera:Pentatomidae), on frozen larvae of Spodoptera litura (Fabricius) (Lepidoptera:Noctuidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 27, 303–305 (1992).

Chen, G., Liao, R., Ding, Y., Ren, W. & Mao, Z. A Review of the predatory adaptation and applications of Eocanthecona furcellata (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) as a biological control agent. J. Entomol. Sci. 60 (2025).

Fu, L. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of predatory Arma chinensis. Sci. Data 11, 962 (2024).

Cantón, P. E. & Bonning, B. C. Extraoral digestion: outsourcing the role of the hemipteran midgut. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 41, 86–91 (2020).

Guo, Y., Xiao, J., Li, D. & Wang, J. The complete mitochondrial genome of the stink bug Eocanthecona furcellata (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 6, 3085–3086 (2021).

Ho, H.-Y., Hsu, Y.-C., Chuang, Y.-C. & Chow, Y.-S. Effect of rearing conditions on production of sternal gland secretion, and identification of minor components in the sternal gland secretion of the predatory stink bug Eocanthecona furcellata. J. Chem. Ecol. 31, 29–37 (2005).

Ho, H.-Y., Kou, R. & Tseng, H.-K. Semiochemicals from the predatory stink bug Eocanthecona furcellata (Wolff): Components of metathoracic gland, dorsal abdominal gland, and sternal gland secretions. J. Chem. Ecol. 29, 2101–2114 (2003).

Wen, J., Chen, K.-W., Fu, L. & Chen, Y. Exposure of Eocanthecona furcellata (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) nymphs and adults to high temperatures induces an aestivo-hibernal egg diapause: a strategy for surviving hot summers. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 52, 457–467 (2017).

Zhu, Y., Wen, J., Luo, Q., Kuang, Z. & Chen, K. Low-temperature-induced winter dormancy in a predatory stink bug Eocanthecona furcellata (Wolff) in the subtropics. Agronomy 13, 2573 (2023).

Gani, M., Gupta, R. K., Kaul, V. & Bali, K. Effect of passage through the gut of Eocanthecona furcellata on Spodoptera litura multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus infectivity and its subsequent dissemination. Phytoparasitica 41, 327–335 (2013).

Gupta, R. K., Gani, M., Jasrotia, P. & Srivastava, K. Development of the predator Eocanthecona furcellata on different proportions of nucleopolyhedrovirus infected Spodoptera litura larvae and potential for predator dissemination of virus in the field. BioControl 58, 543–552 (2013).

Gupta, R. K., Mudasir, G., Jasrotia, P., Srivastava, K. & Kaul, V. A comparison of infectivity between polyhedra of the Spodoptera litura multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus before and after passage through the gut of the stink bug, Eocanthecona furcellata. J. Insect Sci. 14, 1–8 (2014).

Xu, S. et al. Sublethal effect of chlorpyrifos on predatory behavior and physiology of Eocanthecona furcellata (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 117, 156–166 (2024).

Pang, R. et al. Decreased cuticular penetration minimizes the impact of the pyrethroid insecticide λ-cyhalothrin on the insect predator Eocanthecona furcellata. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 249, 114369 (2023).

Yao, Q. et al. Predatory stink bug, Eocanthecona furcellata (Wolff) responses to oral exposure route of λ-cyhalothrin via sex-specific modulation manner. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 192, 105381 (2023).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 11, 1432 (2020).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Roach, M. J., Schmidt, S. A. & Borneman, A. R. Purge Haplotigs: allelic contig reassignment for third-gen diploid genome assemblies. BMC Bioinformatics 19, 460 (2018).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PloS one 9, e112963 (2014).

Vaser, R., Sović, I., Nagarajan, N. & Šikić, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome res. 27, 737–746 (2017).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Zhang, X., Zhang, S., Zhao, Q., Ming, R. & Tang, H. Assembly of allele-aware, chromosomal-scale autopolyploid genomes based on Hi-C data. Nat. Plants 5, 833–845 (2019).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Juicebox.js provides a cloud-based visualization system for Hi-C data. Cell Syst. 6, 256–258.e251 (2018).

Bergman, C. M. & Quesneville, H. Discovering and detecting transposable elements in genome sequences. Brief. Bioinform. 8, 382–392 (2007).

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C. & Pevzner, P. A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, i351–i358 (2005).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_FINDER_parallel: parallelization of LTR_FINDER enabling rapid identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Mobile DNA 10, 48 (2019).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580 (1999).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915 (2019).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295 (2015).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_928085145.1 (2022).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_902806785.1 (2020).

Ferguson, K. B. et al. Jekyll or Hyde? The genome (and more) of Nesidiocoris tenuis, a zoophytophagous predatory bug that is both a biological control agent and a pest. Insect Mol. Biol. 30, 188–209 (2021).

Shumate, A. & Salzberg, S. L. Liftoff: accurate mapping of gene annotations. Bioinformatics 37, 1639–1643 (2021).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W435–W439 (2006).

Holt, C. & Yandell, M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 491 (2011).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H.-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 18, 366–368 (2021).

Mistry, J., Finn, R. D., Eddy, S. R., Bateman, A. & Punta, M. Challenges in homology search: HMMER3 and convergent evolution of coiled-coil regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e121–e121 (2013).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBPZNH000000000 (2025).

Cao, J. D. et al. Eocanthecona furcellata genome data. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29512190.v1 (2025).

Cao, J. D. et al. NGS and HiFi and HiC sequencing data for Cantheconidae furcellata female and male genome assemble. NGDC https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA013912 (2025).

Cao, J. D. et al. DNBSEQ eukaryotic chain specific transcriptome resequencing of the Eocanthecona furcellata. NGDC https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA025568 (2025).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: A highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant physiol. 176, 1410–1422 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Yunnan Tobacco Company Science and Technology Program (2023530000241012) for support of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.C. and Z.M. designed the study; J.Z. and Y.C. collected and reared samples in laboratory for sequencing; R.L., G.F. and Y.L. assembled and annotated the genome; J.C. and R.L. wrote the draft manuscript; G.C., Z.M., J.Z., Y.C., G.F. and Y.L. revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, J., Liao, R., Fu, G. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of predatory Eocanthecona furcellata. Sci Data 12, 1621 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05919-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05919-4