Abstract

This work describes a publicly available dataset, the Duke University Cervical Spine MRI Segmentation Dataset (CSpineSeg), consisting of 1,255 cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations from 1,232 patients collected from the Duke University Health System. CSpineSeg also includes expert manual semantic segmentations of vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs for 481 patients. This dataset aims to provide a resource for training and evaluation of deep learning segmentation models and facilitate cervical spine research. Along with the dataset, we present a deep learning segmentation model which could be used as a benchmark in cervical spine segmentation tasks. Our segmentation model achieves a Dice Coefficient of 0.916, demonstrating the feasibility of utilizing CSpineSeg to train segmentation models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is essential for diagnosis of cervical spine diseases including degenerative spondylosis, spinal infection, and spinal tumors1,2,3,4. Recently, there has been considerable interest in quantitative analysis of MRI to improve and standardize radiologic assessment of cervical spine diseases with most efforts focusing on degenerative spondylosis2,5. Unfortunately, detailed anatomic segmentation is required for many such analyses and is prohibitively time consuming to perform manually.

Deep learning enabled automated segmentation could greatly facilitate cervical spine MRI analysis tasks such as quantification of degenerative disc disease. However, only a limited number of studies in literature have explored automated methods for cervical spine MRI segmentation6,7,8,9 or total spine segmentation on MRI that included cervical spine10,11,12. To the best of our knowledge, there is no publicly available dataset on cervical spine MRI with comprehensive vertebral body and intervertebral discs segmentation to develop and evaluate these methods.

Here we present the Duke University Cervical Spine MRI Segmentation Dataset (CSpineSeg)13, a publicly available MRI dataset comprising 1,255 sagittal T2-weighted cervical spine MRIs from 1,232 patients along with semantic segmentations of vertebral bodies and inter-vertebrae discs. Approximately 40% of the data were manually annotated and verified by expert radiologists with experience in spine imaging. A deep learning segmentation model on vertebral bodies was trained and evaluated on manually annotated data. The best performing model was used to generate segmentations on the remaining unannotated data.

CSpineSeg13 differs from existing related spinal image segmentation datasets in that it focuses entirely on MRI rather than CT14,15,16. While automated segmentation models already exist for CT, these models are not easily translated to MRI. Given the importance of MRI for evaluating cervical spine diseases, particularly degenerative spondylosis, CSpineSeg13 fills an important, unmet need in cervical spine imaging research. In addition to the source imaging data, we also provide expert manual segmentations of relevant vertebral anatomy and a pre-trained model that can be used to automatically segment additional studies.

Methods

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Duke University (Protocol Number: Pro00106785) with a waiver of informed consent.

Data collection

From December 2019 to November 2020, we initially identified 1,326 MRI examinations with the study description “MRI CERVICAL SPINE WITHOUT CONTRAST” via systematic search of the electronic health record database at Duke University. MRI exams were downloaded from the institutional imaging archive and manually reviewed for accuracy. To retrieve sequential cervical spine MRIs within a specific date range, we utilized two DICOM fields, namely’Study Description’ and’Study Date’, to construct a targeted query. This query was executed through the vendor neutral archive (VNA) application programming interface (API) hosted by Duke University. We programmatically utilized the’Study Description’ tag to focus on sagittal T2-weighted series without fat saturation for inclusion in the dataset. First, we selected candidate series by filtering the “Study Description” that included the string “sag T2”. Then, the designated radiologist manually verified the sequence type. We also utilized the’Study Date’ tag to filter the study date range. Each examination includes various series of DICOM files. Exclusion criteria included missing or incomplete sagittal T2-weighted imaging and exams with a field of view not specifically focused on the cervical spine (e.g. combined cervicothoracic MRI). Figure 1 demonstrates the detailed eligibility criteria for the dataset. 1,255 MRI examinations from 1,232 patients were included in the final dataset. Associated demographic data was retrieved from the EHR using Duke Enterprise Data Unified Content Explorer (DEDUCE) (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2014.07.006).

Patient demographics

Patient demographics are presented in Table 1. The average age was 55 +/− 17 years at the exam level. The youngest patient was 18 and the oldest were greater than 90 years old. 557 (45%) patients were male, and 675 (55%) patients were female. 795 (65%) patients were Caucasian/White, 342 (28%) patients were Black or African American, 24 (2%) patients were Asian, 9 (<1%) patients were American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 1 patient (<1%) was Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. 58 (5%) patients were Hispanic and 1,141 (93%) were non-Hispanic.

Ground-truth annotation

We selected 491/1,255 exams (39%) from 481/1,323 patients (36%) for manual semantic segmentation using a pseudo-random approach (exams were selected by medical record number in alphabetical order). Manual segmentations were performed by six board-certified radiologists (five with fellowship training in neuroradiology and one with fellowship training in musculoskeletal radiology) and one post-doctoral researcher without medical training. The post-doctoral researcher completed the first draft of the annotations, which were subsequently reviewed and revised by one of the radiologists.

Segmentation was performed using the publicly available ITK-Snap software tool. Semantic segmentation labels included vertebral bodies (label value 1), and intervertebral discs (label value 2) as demonstrated in Fig. 2. Vertebral bodies were defined as all portions of the vertebral body visible on imaging including any osteophytes but excluding the pedicles and posterior elements. Annotators were instructed to ensure segmentation of the vertebral bodies was performed from at least C2 to T1, and that the segmentation included the entire vertebral body up to the junction with the pedicle and included the uncovertebral joints. Segmentation of C1 was intentionally excluded due to the lack of corpus. Intervertebral discs were defined as all visible disc space including any disc bulge/herniation or intradiscal fluid/gas. The intervertebral disc segmentations were to include the entire disc, with associated herniations, disc-osteophyte complexes, and adjacent vertebral endplates. The posterior longitudinal ligament was not included in the disc segmentations. Fusion across two or more vertebral segments was treated as a single “block” vertebral segment. Surgical hardware was excluded from the segmentations. The segmentation process focused on anatomy rather than disease-focused objectives.

The series descriptors identified in the annotation dataset were utilized to select the un-annotated dataset for automated labeling. All final manual segmentations were reviewed and approved by one of the six radiologist annotators. The mid-sagittal slice of all unannotated exams was reviewed for quality and consistency by one of the six experts.

Segmentation experiments and evaluation

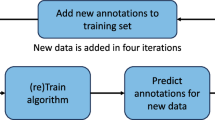

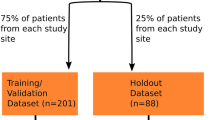

Manually annotated cervical spine exams were randomly split into a development set (391/491, 80%) and a test set (100/491, 20%). Development set data was used to train and validate a deep learning segmentation model using pre-processing pipelines and five-fold cross validation implemented in nnU-Net17. Both 2D and 3D U-Net models were trained for 1000 epochs without early stopping. We evaluated the 2D and 3D models separately as well as an ensemble of both, which takes the average of softmax probabilities from the model outputs17. Evaluation was performed on the test set with the Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) as the primary metric. The best performing segmentation model was applied to the remaining unannotated data. We reported the mean and standard deviation of the DSC scores. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests18 were applied to test the difference between non-normally distributed DSC scores of different model configurations. The confidence level was set at 95%.

Data Records

The Duke University Cervical Spine MRI Segmentation Dataset (CSpineSeg)13 is publicly available to facilitate research in cervical spine imaging research. Data is publicly available on Medical Imaging and Data Resource Center (MIDRC, https://doi.org/10.60701/H6K0-A61V), medical imaging data commons funded by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB). MRI data adheres to the DICOM format and has undergone thorough de-identification procedures via RSNA DICOM anonymizer tool (Version 16, https://github.com/RSNA/mirc.rsna.org/Anonymizer-installer.jar), with modifications to dates that preserve the temporal interval between scans for the same patient. Deidentified data were strictly reviewed and verified by the institution. Users can download the full dataset via https://doi.org/10.60701/H6K0-A61V under the title “Duke-CspineSeg”. Four data download links of compressed files were provided, including Structured Data TSVs, MRI Image Files, Segmentation Files, and Annotation Files. We demonstrated the file structure in Fig. 3.

The file directory tree of the dataset folder, with an example of the case “593973-000003” in the dataset. “DukeCSpineSeg_structured” stored metadata of the dataset into 6 tab-delimited files. “DukeCSpineSeg_imaging_files” stored DICOM files for each study of this patient. Original DICOM files were saved in a compressed “.zip” file. After decompressing the zip file, users can get access to the original 14 DICOM files for this series of the study. “DukeCSpineSeg_annotation” stored the converted NIfTI file from the 14 DICOM files and “DukeCSpineSeg_segmentation” stored the annotation masks in NIfTI format.

Structured Data TSVs

Six structured metadata files in tab-delimited format are included in this download link to record metadata for the dataset. Specifically, demographic information (e.g. age_at_index, sex, race, ethnicity) is available in Clinical_manifest_RSNA_20250321.tsv and the imaging parameters (e.g. echo time, repetition time, slice thickness, spacing_between_slices, manufacturer, etc.) are available in mr_series_RSNA_20250321.tsv. MIDRC generates the codebook for recording metadata by using the in-house developed data dictionary model (available on https://github.com/uc-cdis/midrc_dictionary) and the visual tabular representation (available on the MIDRC data portal https://data.midrc.org/DD).

MRI image files

Users can access de-identified DICOM files in this folder. The file directory follows the following structure: “./case_image/{Patient_ID}/{Study_Instance_UID}/{Series_Instance_UID}.zip”, where we fetched Patient_ID, Study_Instance_UID, and Series_Instance_UID from the attributes stored in de-identified DICOM files. After unzipping the file, users can obtain a sequence of DICOM files.

Annotation files

This is a flat directory that stores the original MRI in NIfTI format, converted by using dcm2niix19. We selected the following de-identified DICOM attributes, Patient_ID, Accession_Number, Series Number, and Instance Number, from the de-identified DICOM files for naming each converted NIfTI file using the following format: “{Patient_ID}/Study-MR-{Accession_Number}/Series-{Series_Number}/{Instance_Number}.nii.gz”.

Segmentation files

This is a flat directory that stores the segmentation of each NIfTI image in Annotation Files. The segmentation files are stored in NIfTI format, with a suffix “_SEG” attached to the original file name before the “.nii.gz” extension.

Technical Validation

Deep learning segmentation performance

We demonstrate our segmentation model performance in Table 2. All three model configurations performed well. The ensembled outputs reach the best performance for segmentation of vertebral bodies (DSC = 0.929), intervertebral discs (DSC = 0.904), and the macro-average of both labels (DSC = 0.916), with comparable differences from the other two configurations (P-value > 0.05 from non-parametric tests). Robust performance was found in cross validation folds (Supplementary Materials A.). Figure 4 demonstrated the DSC distributions in vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs. The segmentation performance was comparable to previously published work on vertebrae segmentation of lumbar spine20,21,22.

Limitation and future work direction

CSpineSeg13 has the following limitations. First, the labeling of vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs is binary without classification of vertebral level (i.e. C1-C7). Future work can focus on the classification using either manual efforts or automated methods, for example using connected component analysis. We have briefly explored the connected component method and provided preliminary results for per-intervertebral-disc segmentation based on the middle slice of the test cases (Supplementary Materials B.). We hope that this method can be further utilized and refined in future studies. Second, the automatically labeled data generated from this model have not undergone manual review and should be considered as “weakly” labeled data. Specific usage of the weakly labeled data should be under discretion. Third, the provided annotations were anatomical rather than pathological. We did not consider the presence or absence of cervical spine pathology in this dataset, and individual exams are not labeled for pathology. Future label extensions, such as adding pathological labels by expert review, analyzing Modic changes23, or grading intervertebral discs degeneration using Pfirrmann grading system24, are feasible for downstream clinical analysis. Fourth, manual annotations of each exam were verified by one of the six board-certified readers. This workflow reflects the practice of a common radiology exam evaluation process, but it lacks multi-rater variability evaluations. We are happy to address any potential annotation issues discovered in the future.

Usage Notes

To download the dataset on MIDRC, users must register and log into their account. Users are required to strictly follow the MIDRC Data Use Agreement (https://www.midrc.org/midrc-data-use-agreement) when accessing and using the de-identified data. DICOM files of one series can be visualized in ITK-SNAP by importing the series folder. To correctly visualize the segmentation annotation, users are recommended to import MRI NIfTI as the main image and load its associated segmentation NIfTI as the segmentation in ITK-SNAP, in which Label 1 (red) represents vertebral bodies and Label 2 (green) represents inter-vertebrae discs. We used nnU-Net V2 (https://github.com/MIC-DKFZ/nnUNet/tree/master/nnunetv2) for this work. Previously trained model weights can be accessed via google drive upon reasonable requests.

Both the test set and the weakly labeled set were collected from our institution. Thus, we believe that the high performance of the trained segmentation model (DSC >90%) on the test set could reflect the high quality of the weakly labeled data. However, due to the limited radiologists’ availability, the weakly labeled data were not evaluated by our annotation team. Thus, we recommend additional manual reviews to refine the weakly-labeled data. This process can be accelerated by using an active learning framework25. Additionally, by combining both weakly and strongly labeled data, semi-supervised learning approaches can be applied to refine the segmentation models26,27,28.

Data availability

The Duke University Cervical Spine MRI Segmentation Dataset (CSpineSeg)13 is publicly available at MIDRC: https://doi.org/10.60701/H6K0-A61V. Four downloadable links are provided to include structured data (Structured Data TSVs), DICOM data (MRI Image Files), converted NIfTI format of DICOM data (Annotation Files), and segmentation data (Segmentation Files) in NIfTI format. Additional details regarding the access and usage of the data are described in the data records section.

Code availability

We provided the following sample code and a pseudo data directory which has the same folder structure as the published dataset on https://github.com/JikaiZ/CSpineSeg. The dataset can be accessed using the following URL: https://data.midrc.org/discovery/H6K0-A61V.

• dicom_nifti_dcm2niix.py: This script converts a series of DICOM files to one NIfTI file using “dcm2niix” toolkit. Users need to specify the input folder path that contains the original DICOM files, the output folder path, and a pandas dataframe that records basic information of the DICOM files.

• nnUNet_Setup.py: This script organizes the input NIfTI files for nnU-Net pipeline into a separate folder. Users need to specify the location of the input NIfTI files, and the development (training + validation) plus the test set for training/validating a nnU-Net model. Other customizable configurations include the dataset id, task name, and folders that save training/testing/un-annotated images.

• nnUNet_env_set.sh: This script includes command lines that implements nnU-Net, including preprocessing, training of 2 d and 3d_fullres models, and inference using 2 d, 3d_fullres and ensembled outputs of both.

References

Kaiser, J. A. & Holland, B. A. Imaging of the Cervical Spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 23(24). https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/fulltext/1998/12150/imaging_of_the_cervical_spine.9.aspx (1998).

Ellingson, B. M., Salamon, N. & Holly, L. T. Advances in MR imaging for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. European Spine Journal. 24(2), 197–208, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-013-2915-1 (2015).

Nouri, A., Martin, A. R., Mikulis, D. & Fehlings, M. G. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of degenerative cervical myelopathy: a review of structural changes and measurement techniques. Neurosurgical Focus FOC. 40(6), E5, https://doi.org/10.3171/2016.3.FOCUS1667 (2016).

Rüegg, T. B., Wicki, A. G., Aebli, N., Wisianowsky, C. & Krebs, J. The diagnostic value of magnetic resonance imaging measurements for assessing cervical spinal canal stenosis. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine SPI. 22(3), 230–236, https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.10.SPINE14346 (2015).

Khan, A. F. et al. Utility of MRI in Quantifying Tissue Injury in Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy. J Clin Med. 12(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093337 (2023).

Andrew, J., DivyaVarshini, M., Barjo, P. & Tigga, I. Spine Magnetic Resonance Image Segmentation Using Deep Learning Techniques. In: 2020 6th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS). 945–950. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACCS48705.2020.9074218 (2020).

Zhu, Y. et al. A quantitative evaluation of the deep learning model of segmentation and measurement of cervical spine MRI in healthy adults. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 25(3), e14282, https://doi.org/10.1002/acm2.14282 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. SeUneter: Channel attentive U-Net for instance segmentation of the cervical spine MRI medical image. Front Physiol. 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.1081441 (2022).

Huang, S. H., Chu, Y. H., Lai, S. H. & Novak, C. L. Learning-Based Vertebra Detection and Iterative Normalized-Cut Segmentation for Spinal MRI. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 28(10), 1595–1605, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2009.2023362 (2009).

Warszawer, Y. et al. TotalSpineSeg: Robust Spine Segmentation with Landmark-Based Labeling in MRI. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31318.56649 (2025).

Möller, H. et al. SPINEPS—automatic whole spine segmentation of T2-weighted MR images using a two-phase approach to multi-class semantic and instance segmentation. Eur Radiol. 35(3), 1178–1189, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-024-11155-y (2025).

Graf, R. et al. Denoising diffusion-based MRI to CT image translation enables automated spinal segmentation. Eur Radiol Exp. 7(1), 70, https://doi.org/10.1186/s41747-023-00385-2 (2023).

Zhou, L. et al. The Duke University Cervical Spine MRI Segmentation Dataset (CSpineSeg). MIDRC. https://doi.org/10.60701/H6K0-A61V.

Sekuboyina, A. et al. VerSe: a vertebrae labelling and segmentation benchmark for multi-detector CT images. Med Image Anal. 73, 102166 (2021).

Deng, Y. et al. CTSpine1K: a large-scale dataset for spinal vertebrae segmentation in computed tomography. arXiv preprint arXiv:210514711 (2021).

Lin, H. M. et al. The RSNA Cervical Spine Fracture CT Dataset. Radiol Artif Intell. 5(5), e230034, https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.230034 (2023).

Isensee, F., Jaeger, P. F., Kohl, S. A. A., Petersen, J. & Maier-Hein, K. H. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat Methods. 18(2), 203–211, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01008-z (2021).

McKnight, P. E. & Najab, J. Mann-Whitney U Test. In: The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. 1-1. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0524 (2010).

Li, X., Morgan, P. S., Ashburner, J., Smith, J. & Rorden, C. The first step for neuroimaging data analysis: DICOM to NIfTI conversion. J Neurosci Methods. 264, 47–56, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.03.001 (2016).

Huang, J. et al. Spine Explorer: a deep learning based fully automated program for efficient and reliable quantifications of the vertebrae and discs on sagittal lumbar spine MR images. The Spine Journal. 20(4), 590–599, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2019.11.010 (2020).

Lu, J. T. et al. Deep Spine: Automated Lumbar Vertebral Segmentation, Disc-Level Designation, and Spinal Stenosis Grading using Deep Learning. In: Doshi-Velez, F., Fackler, J., Jung, K. et al. eds. Proceedings of the 3rd Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference. Vol 85. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. PMLR; 403–419, https://proceedings.mlr.press/v85/lu18a.html (2018).

Li, H. et al. Automatic lumbar spinal MRI image segmentation with a multi-scale attention network. Neural Comput Appl. 33(18), 11589–11602, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-021-05856-4 (2021).

Udby, P. M. et al. A definition and clinical grading of Modic changes. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 40(2), 301–307, https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.25240 (2022).

Griffith, J. F. et al. Modified Pfirrmann Grading System for Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 32(24). https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/fulltext/2007/11150/modified_pfirrmann_grading_system_for_lumbar.28.aspx (2007).

Yang, L., Zhang, Y., Chen, J., Zhang, S. & Chen, D. Z. Suggestive Annotation: A Deep Active Learning Framework for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In: Descoteaux, M., Maier-Hein, L., Franz, A., Jannin, P., Collins, D. L., Duchesne, S., eds. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention − MICCAI 2017. 399-407 (Springer International Publishing; 2017).

Papandreou, G., Chen, L. C., Murphy, K. P. & Yuille, A. L. Weakly-and semi-supervised learning of a deep convolutional network for semantic image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. 1742–1750 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Semi-supervised semantic segmentation using unreliable pseudo-labels. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 4248–4257 (2022).

Shen, W. et al. A Survey on Label-Efficient Deep Image Segmentation: Bridging the Gap Between Weak Supervision and Dense Prediction. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 45(8), 9284–9305, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3246102 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. and W.W. curated the dataset and drafted the initial manuscript. Maciej. M. supervised and provided mentorship. L.Z. completed initial annotations. W.W. led the annotation team and worked with R.C., J.W., A.D., Michael M., and E.C. to finalize the annotations. J.Z. and H.G. cleaned and organized the dataset. J.Z. de-identified the dataset, trained the segmentation model, and performed analysis. E.C. and J.Z. finalized the manuscript, prepared the final version of the dataset and worked with MIDRC to publish the dataset. E.C. oversaw the final analysis, manuscript and the dataset. All authors contributed to editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., Wiggins, W., Zhang, J. et al. The Duke University Cervical Spine MRI Segmentation Dataset (CSpineSeg). Sci Data 12, 1695 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05975-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05975-w