Abstract

Soil salinization leads to land degradation, reduced agricultural productivity, and heightened food security risks. Accurate assessment of saline soil distribution and severity is critical for sustainable land management. However, challenges such as broad spatial extent, high heterogeneity, and limited field observations hinder mapping accuracy. Existing datasets in China show large discrepancies in salinized area estimates due to coarse spatial and temporal resolution. In this study, we classified soil salinity degree across the western Songnen Plain from 1985 to 2024 using field surveys, remote sensing imagery, and machine learning algorithms, achieving high accuracy (overall accuracy = 0.893, Kappa = 0.782). A regional soil EC prediction model (R2 = 0.467) was developed using 942 in situ samples and remotely sensed indicators, accounting for soil moisture effects. This model produced annual, 100 m resolution maps from 1985 to 2024, with only 2.78% deviation from the second National Land Survey. The resulting high-resolution dataset reveals the spatiotemporal dynamics of soil salinity and supports improved monitoring and management to address environmental sustainability and food security.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Soil salinization is a major form of land degradation with wide-reaching impacts on global food security, ecological health, and sustainable land use1. Excessive salt accumulation disrupts soil structure, reduces fertility, impairs crop productivity, and contributes to land abandonment in arid and semi-arid regions. The scale and severity of this problem are underscored by estimates from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)2 and UNESCO3, which suggest that approximately 7% of the world’s soils and nearly 30% of irrigated land are affected by salinity, causing billions of dollars in annual agricultural losses. With the compounding effects of climate change—particularly warming, evapotranspiration intensification, and changing precipitation patterns—salinization is projected to intensify further in the coming decades.

China’s Songnen Plain is among the three largest saline-alkali regions globally and is one of the most severely salinized agricultural zones in the country4. The western part of this region, characterized by flat terrain, poor drainage, shallow groundwater, and high evaporation rates, is especially vulnerable to secondary salinization5. Between 19546 and 20167,8, the estimated area of saline soils in the region increased from ~4,000 km2 to over 12,000 km2. However, substantial disagreement exists across previous regional and global estimates due to differences in methods, resolution, and data sources. For example, two widely used existing global soil salinity datasets—the Soil Salinity and Sodicity on a Global Scale (SSSG)9 and the Long-term Dynamics of Soil Salinity and Sodicity (LDSS)10,11—report drastically different salinized areas for Jilin Province in 2009 (7,208 km2 vs. 73 km2, respectively), highlighting the inadequacy of global products for fine-scale regional monitoring.

Reliable, high-resolution data on salinity extent and intensity are essential for understanding spatiotemporal salinity dynamics, assessing land degradation risk, and informing precision agriculture and land management strategies12. While field-based soil electrical conductivity (EC, a 1:5 soil-to-water suspension) measurements are the standard for salinity assessment, large-scale monitoring via field campaigns is often logistically and financially impractical. Advances in remote sensing and machine learning offer viable alternatives for scalable salinity prediction, particularly when supported by consistent multitemporal satellite imagery and ground-truth observations13,14.

Here, we present a multiyear, high-resolution (100 m) soil salinity degree for the western Songnen Plain spanning 1985 to 2024. The dataset is based on extensive field sampling campaigns conducted over multiple years, in combination with Landsat series satellite imagery (TM and OLI). The core variable estimated is EC. EC values were modeled using spectral features, salinity indices, and a drought-sensitive soil moisture proxy15—Perpendicular Drought Index (PDI)16—to improve prediction accuracy in sparsely vegetated and bare-soil areas17.

To support predictive mapping, we evaluated eight machine learning algorithms, including Neural Network Fitting (NNF), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), Least Squares Boosting (LSBoost), Kernel Partial Least Squares (KPLS), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and others. The NNF model demonstrated the best performance during training–validation (R2 = 0.467; RMSE = 0.729 dS m−1). This modeling framework was applied annually across the study period using Landsat time-series data, resulting in a temporally continuous archive of EC values and salinity degree maps at five standard salinity levels (non-saline to extremely saline) following the U.S. Salinity Laboratory’s guidelines18.

This dataset addresses key gaps in existing regional and global salinity products by providing: a) Higher spatial resolution (100 m) than existing global datasets (typically 250 m to 1 km), b) Annual temporal resolution from 1985–2024, capturing interannual and long-term variability, c) Modeling informed by multiyear field data, reducing uncertainty from single-year calibration, d) Consideration of soil moisture effects via PDI, improving prediction reliability under variable surface conditions.

In addition, the methodological framework can be extended to other arid and semi-arid regions facing similar soil salinity challenges, especially where long-term satellite data and partial field surveys are available. By integrating consistent spectral, topographic, and drought indicators into a validated modeling pipeline, the approach provides a transferable solution for generating local-scale soil salinity maps over long time series.

Methods

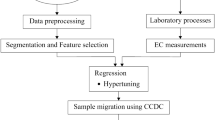

Figure 1 illustrates the workflow for generating the long-term soil salinity dataset. In this study, we implemented two distinct predictive tasks: saline soil identification and salinity degree prediction. For the saline soil identification task, a total of 1,570 saline and 1,917 non-saline reference points were carefully selected through visual interpretation of high-resolution imagery in Google Earth Pro. These reference samples were used to train a binary classification model using machine learning algorithms. For the salinity degree prediction task, we constructed a prediction model to estimate soil EC using 942 field sampling points representing the major soil classification units and land cover categories across the region. Both models were applied to annual Landsat satellite data from 1985–2024, enabling the reconstruction of interannual dynamics in soil salinity across the western Songnen Plain. The final outputs include yearly maps of saline soil distribution and salinity degree.

Study area

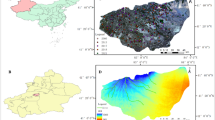

The Western Songnen Plain (longitude 121°38′–126°11′ E, latitude 43°59′–46°18′ N) is one of the world’s three major saline soil regions and the area most severely affected by salinization in China, covering approximately 46,985 km2 (Fig. 2). There are two cities in the region: Songyuan and Baicheng. This low-lying plain experiences a temperate continental monsoon climate, characterized by low annual precipitation and intense surface evaporation, nearly three times the annual precipitation19. River systems contribute to salt accumulation as pooling and settling occur in the region. High evaporation rates cause groundwater to rise, depositing salts on the soil surface and forming saline soils. The severe imbalance between evaporation and precipitation, combined with human activities and other contributing factors, has made the Western Songnen Plain a hotspot for saline soil distribution. According to the China Land Cover Dataset (CLCD)20, the Western Songnen Plain is primarily composed of four land cover types: cropland, grassland, barren, and wetland. Based on the FAO90 soil classification system21, the dominant soil groups in this region include Chernozems (CH), Phaeozems (PH), Arenosols (AR), and Solonetz (SN). The complex interplay among climatic, hydrological, edaphic, and anthropogenic factors has led to highly heterogeneous spatial patterns of soil salinity across the landscape. These environmental gradients and land use variations collectively shape the extent, severity, and dynamics of soil salinization in this ecologically fragile region.

Data acquisition

Saline soil identification points

To support model training and validation, a total of 3,487 reference samples were delineated, including 1,570 saline and 1,917 non-saline points, using high-resolution imagery from Google Earth Pro (Fig. 2e). The entire study area was covered by cloud-free scenes from 2020, which served as the reference year for point selection.

A semi-automated, rule-based visual interpretation approach was applied to reduce subjectivity and improve consistency. This method integrated spectral and phenological characteristics known to be indicative of salinity:

-

Spectral characteristics: Saline soil typically show high reflectance in the blue and green bands due to presence of salt crusts and surface desiccation. These features are well-established in prior salinity mapping studies.

-

Vegetation masking (NIR-R-G false-color composite): We applied false-color composite (R = NIR, G = Red, B = Green) to discriminate vegetated surface, which appear bright red. This effectively separates vegetation from bare saline surfaces, reducing false positives and improving interpretation consistency.

All selected points were georeferenced and extracted as coordinate shapefiles, and their corresponding spectral features were used to generate remote sensing feature vectors for model training and testing.

Soil EC sampling points

To support the spatial modelling of soil salinity, a total of 942 georeferenced soil samples were collected across the western Songnen plain in 2012, 2014, 2018 and 2019. The sampling strategy and laboratory procedures followed standardized procedures to ensure methodological reproducibility and data reliability.

Field Sampling Protocol

-

1.

Site Selection, Spatial Design, and Preparation: A dual-stratification approach was adopted to capture the heterogeneity of salinized region, combining land cover types and soil classification units as the two stratifying criteria. Sampling sites were selected to ensure each point corresponding to a unique 30 m × 30 m Landsat grid cell, with no two samples located within the same pixel (Fig. 3). At each site, surface debris (e.g., leaves, plant roots) was removed to avoid contamination. To enhance spatial representativeness and reduce microsite variability, three sub-samples were collected within in a diagonal arrangement22 and thoroughly mixed to form a composite sample.

-

2.

Soil Core Extraction: A stainless-steel ring cutter (100 cm3) was vertically inserted into the soil to a depth of approximately 5 cm using a rubber mallet. To preserve core integrity, surrounding soil was carefully excavated with a profiling knife.

-

3.

Sample Handling and Storage: Excess soil was trimmed flush with the edges of the ring. Each core was sealed with plastic caps on both ends, labeled, and placed in individual self-sealing plastic bags. Three such cores from each site were combined and stored in a larger sealed bag for laboratory analysis.

Laboratory Measurement of EC1:5

Each composite sample was first air-dried and then oven-dried at 105 °C for 48 hours to remove residual moisture. The dried samples were ground and passed through a 2 mm sieve. For EC1:5 determination, 10 g of sieved soil was mixed with 50 mL of deionized water yielding a 1:5 soil to water ratio, shaken, and left to equilibrate for 2 hours. The supernatant was then extracted, and the EC1:5 was measured using a calibrated conductivity meter (DDS-307A, Light Magnetic Instruments, China). Instrument calibration was performed before each batch using standard KCl solution (1413 μS cm−1). All measurements were conducted at room temperature (~25 °C), and instrument drift was checked periodically using control samples.

This standardized approach yielded a high-quality, spatially representative dataset of 942 EC1:5 values, which served as the calibration and validation basis for remote sensing–based salinity modeling, with all values hereafter referred to as EC (Table 1).

Compositing procedures for annual imagery

To monitor the spatiotemporal changes of saline soils in the Western Songnen Plain from 1985 to 2024, we evaluated available satellite datasets for their spatiotemporal and spectral resolutions. Landsat-5 TM and Landsat-8 OLI/TIRS were ultimately selected as the primary data sources (Table 2).

To ensure the spatial and temporal consistency of the dataset, we implemented a multi-step strategy using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform to fill such gaps in a scientifically defensible manner. Our approach is described below:

-

1.

Bare-soil period window selection

To reduce interference from vegetation and other surface cover, we focused on images captured during the bare soil period, specifically, after the September harvest23 and before the November snowfall24. We generated annual composites by computing the mean reflectance of all valid, cloud-free pixels25 within the bare soil period time window26. This method reduced random noise and improved the signal-to-noise ratio for each year while maintaining phenological comparability.

To further minimize vegetation and snow interference, we generated 5-day composite images and visually inspected them for signs of vegetation or snow cover. If vegetation interference was detected, the beginning of the window was postponed by 5 days. If snow was observed, the window’s end was advanced by 5 days. This adaptive approach ensures that interannual variability in phenology and climate is accounted for, thereby maximizing bare soil coverage and improving the reliability of soil EC prediction.

-

2.

Annual composite generation

Firstly, preprocess the Landsat-5 TM and Landsat-8 OLI/TIRS data. Radiometric calibration was applied to Landsat-5 TM and Landsat-8 OLI/TIRS data. Next, atmospheric corrections were performed using LEDAPS27 for Landsat-5 and LaSRC28 for Landsat-8. This included masking for clouds, shadows, water and snow using CFMASK, as well as applying per-pixel saturation masks. Finally, geometric and orthographic corrections were conducted to ensure spatial accuracy.

To address spectral differences between Landsat-5 TM and Landsat-8 OLI/TIRS sensors, reflectance matching was performed using Pseudo Invariant Areas (PIA)29,30,31. Spectral differences were analyzed, and reflectance matching coefficients were derived using a linear regression model. Water bodies and impervious surfaces were used to match the reflectance of thermal infrared (TIR) band, while visible and near-infrared bands required additional adjustments. High-quality, small-area Landsat-7 ETM+ imagery was incorporated, and bare soil area from the same time period were analyzed to improve reflectance matching accuracy (Table 3).

Table 3 Reflectance matching coefficients between Landsat-8 OLI/TIRS and Landsat-5 TM imagery. Additionally, Landsat-7 ETM+ images after 2003 were affected by striping caused by the SLC-off (Scan Line Corrector-off) malfunction. To bridge single-year gap (2012) without relying on Landsat-7, we applied a simple temporal averaging strategy using reflectance-corrected Landsat-5 TM (2011) and Landsat-8 OLI/TIRS (2013) images. This averaging was conducted only for bare-soil conditions and used as an auxiliary step for band harmonization.

-

3.

Temporal gap filling for persistent cloud coverage

Since a single image could not cover the entire study area, we selected high quality images from GEE using mean value synthesis. The QA band was used to remove pixels affected by clouds and cloud shadows. For pixels with missing observations due to persistent cloud cover:

-

We slightly extended the temporal window within the same year if additional cloud-free scenes became available.

-

If gaps persisted, we incorporated data from adjacent years (±1 year) while maintaining seasonal consistency to avoid introducing phenological mismatches.

-

For each pixel with persistent gaps, the composite reflectance was recalculated by averaging valid observed from both the target year and neighbouring years32, favouring data from the target year when available33.

-

This carefully designed workflow ensures robust and reproducible handling of data gaps, maintaining both spatial completeness and temporal consistency.

Following these processing and correction steps, we obtained annual Landsat images at a consistent 100 m resolution for the Western Songnen Plain, spanning the period from 1985 to 2024. This dataset provides a robust foundation for analyzing the spatiotemporal dynamics of saline soils in the region.

Algorithm model

Saline soil identification model

For the saline soil identification model, six spectral bands—Blue, Green, Red, NIR, SWIR1, and SWIR2—were selected as input features. Four machine learning algorithms were employed for classification: Random Forest (RF)34,35, K-Nearest Neighbour (KNN)36, Classification and Regression Tree (CART)37, and Support Vector Machines (SVM). A total of 70% of the ground data (n = 2,463) were used for model training, while the remaining 30% (n = 1,024) were reserved for testing. In this model, ground truth data points were labeled as “1” for saline soil and “0” for non-saline soil, resulting in a categorical dataset with two discrete classes. Model performance was comprehensively evaluated using multiple metrics, including Overall Accuracy (OA), Kappa coefficient, Producer’s Accuracy (PA), User’s Accuracy (UA), and F1 score (Table 4), to ensure a robust assessment of classification accuracy and model stability.

Saline soils significantly affect vegetation growth, creating pronounced spectral differences in remote sensing imagery. As a result, using imagery captured during the vegetation growing season enhances the detection of soil salinization, producing more accurate identification results. This approach underscores the importance of seasonal timing in remote sensing applications for soil salinity studies.

Soil EC prediction model

To normalize the distribution of the raw soil EC, a natural logarithmic transformation (LnEC) was applied prior to model development38. This transformation helped reduce skewness and stabilize variance, enhancing model robustness. Subsequent correlation analysis indicated that LnEC exhibited stronger associations with remote sensing features compared to the untransformed EC values, thereby improving model sensitivity and prediction accuracy (Table 5). Among all input variables, the TIR band demonstrated the highest correlation coefficient (r = −0.51) and was identified as a key predictor for modeling.

Additionally, the Salinity Index (SIT), known for its strong correlation with varying surface salt concentrations39,40, was included in our model. To account for the effects of soil moisture on remote sensing based estimation41, we incorporated the Perpendicular Drought Index (PDI)15 as a key predictor. PDI quantifies surface dryness by calculating the perpendicular distance from the “soil line” in Red–NIR spectral space16. It is particularly effective in bare and sparsely vegetated regions, where it has been shown strong correlations with both surface soil moisture and meteorological drought indices, especially under arid and semi-arid conditions17. For the sake of model parsimony and to mitigate multicollinearity, PDI was selected as the sole soil moisture-related input variable, replacing commonly used indices such as the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI), the Vegetation Condition Index (VCI), and passive microwave products (e.g., SMAP, ESA CCI SM). This choice ensured minimal redundancy and enhanced the model’s generalizability across spatial and temporal gradients. The PDI and SIT equations are as follows:

where \({R}\) is the Red band, \({N}{I}{R}\) is the NIR band, \({M}\) is the slope of the soil line.

To ensure accurate soil EC predictions, models were developed using eight machine learning algorithms: Neural Net Fitting (NNF)42,43, Gaussian Process Regression (GPR)44, Least-Squares Boosting (LSBoost), Kernel Partial Least Squares Regression (KPLS)45,46,47, Tree, SVM, Linear Regression (LR), and SVM Kernel. A total of 80% of the ground data (n = 754) were used for model training, while the remaining 20% (n = 188) were reserved for testing. To enhance robustness and generalization, we incorporated ten-fold cross-validation results for model accuracy validation. It was a regression model and the model performance was evaluated using key metrics, including the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), mean square error (MSE), and mean absolute error (MAE) (Table 6). This comprehensive evaluation ensured the reliability and accuracy of the regression models for soil EC prediction.

Soil salinity dynamics (1985–2024)

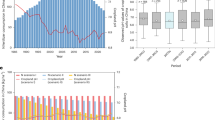

We calculated the annal predicted soil EC values across identified salinized areas from 1985 to 2024. The temporal dynamic of soil salinity exhibited ecologically and agriculturally plausible interannual variability, reflecting logical trends in salinization and desalinization over time. To facilitate interpretation and classification, the predicted EC values were converted to saturated paste extract electrical conductivity (ECe) using an empirical relationship: \({{EC}}_{e}=10.62{EC}\) (R2 = 0.826)48. This allowed classification of soil salinity degree based on the USDA standards. The results revealed clear and distinct spatial-temporal patterns in soil salinization dynamics across the study period (Fig. 4). Key findings include:

-

1985–1998 (Pre-intensification period): Soil salinity remained stable, with median EC values ~0.5 dS m−1 and narrow interquartile ranges. The majority of areas were classified as moderately salinized.

-

1999–2006 (Salinization phase): EC values increased gradually, with medians often > 0.6 dS m−1 and wider spread, this pattern reflects an intensification of salinization, likely driven by expanded irrigation, suggesting worsening salinity likely due to land use intensification and irrigation mismanagement.

-

2007–2024 (Desalinization/ stabilization stage): EC declined and stabilized, with most medians < 0.5 dS m−1, slightly salinized soils became more widespread, possibly reflecting the effect of restoration efforts, such as drainage improvement and crop rotation practices.

These results demonstrate the capability of our modelling framework and dataset to detect and quantify long-term salinity dynamics, offering insights into the spatiotemporal footprint of land management regimes in the Western Songnen Plain over the past four decades49.

Data Records

All datasets, model files, and code have been publicly archived at Zenodo under the https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1704426050. The uploaded data package contains the following primary components:

-

1)

Soil sampling metadata (Table 7)

Table 7 List of soil sampling metadata records. Filename: Soil_EC_sampling_points.csv

Format: CSV (UTF-8 encoded)

Description: Contains georeferenced field observations of soil EC, used for prediction model training and validation.

-

2)

Model files

-

TIRSITPDI_predicted.mat

Format: Matlab.mat file

Description: Contains the trained Neural Network Fitting (NNF) model for soil EC prediction. This model was optimized using 14,000 iterations and parameter tuning (e.g., number of hidden layers, learning rate, activation function).

-

Soil_EC_prediction_model.m

Format: MATLAB script

Description: Implements the prediction process. It reads spectral input parameters (TIR, SIT, PDI), applies the trained model, and outputs predicted soil EC values.

-

3)

Annual Salinity Degree Mapping (1985–2024)

These folders contain annual gridded maps and summary statistics derived from the soil EC prediction model.

Statistical_results_by_year/

Statistical_results_by_year/Contents: CSV tables and a .png summarizing the area (in km2) of saline soils in each salinity degree per year.

Classes: Slightly saline (2–4 dS m−1), Moderately saline (4–8), Highly saline (8–16), Extremely saline (>16)

Salinity_degree_maps/

Salinity_degree_maps/Contents: Raster maps (GeoTIFF, EPSG:4326, 100 m resolution) of classified salinity degree for each year (1985–2024) based on U.S. Salinity Laboratory classification. The .png contains year-by-year salinity degree.

Saline_soil_identification/

Saline_soil_identification/Contents: Binary maps (GeoTIFF) showing annual identification of saline vs. non-saline soils from 1985 to 2024. The .png contains year-by-year identification results.

Technical Validation

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the soil salinity dataset, we conducted a series of validation steps based on standard quality control protocols, statistical evaluation metrics, and cross-referencing with independent datasets.

Quality control of field sampling and laboratory analysis

To ensure the reliability, reproducibility, and scientific robustness of the dataset, supporting its value for future remote sensing and soil EC modeling applications. The following three rigorous quality assurance protocols were used in this study.

-

1.

Field replicates: At each sampling site, three subsamples were collected in a diagonal pattern and composited to reduce microsite variability and enhance spatial representativeness.

-

2.

Instrument calibration: The conductivity meter (DDS-307A, Light Magnetic Instruments, China) was calibrated prior to each measurement batch using a standard KCl solution (1413 μS cm−1) to ensure measurement accuracy.

-

3.

Spatial quality assurance: All GPS coordinates were independently cross-verified and visually inspected against high-resolution satellite imagery to eliminate geolocation outliers or inconsistencies.

Outlier detection and consistency check

To ensure the statistical integrity of the soil salinity dataset, we performed outlier detection using the interquartile range (IQR) method across all 942 field-measured EC values. According the standard rule (values outside Q1 − 1.5 × IQR or above Q3 + 1.5 × IQR), no outliers were detected (Fig. 5), conforming that the dataset spans a representative and statistically valid range of EC variability.

In addition, input feature consistency was evaluated for key remote sensing predictors including thermal infrared reflectance (TIR), SIT, and PDI. Both visual inspection and descriptive statistical summaries were used to ensure internal coherence across years and scenes. No anomalous values or sensor-induced discontinuities were observed, affirming the sensor stability and temporal consistency of the input variables used in model construction.

Model performance assessment

Among the four identification models tested, all achieved high accuracy, with OA exceeding 0.85 and Kappa values above 0.70, indicating reliable identification of saline soils in the study area. Further analysis showed that the RF model achieved the best performance, with an OA of 0.893 and Kappa of 0.782, surpassing KNN, CART, and SVM (Table 8). Based on these results, the RF model was used to accurately delineate the extent of saline soils in the study area.

Among the eight prediction models tested (Table 9), the NNF model, which achieved R2 = 0.467, RMSE = 0.729 dS m−1, and MAE = 0.556 dS m−1, was considered relatively reliable. In contrast, the SVM Kernel model, with R2 = −0.040, RMSE = 0.904 dS m−1, and MAE = 0.559 dS m−1, showed poor reliability.

To ensure model robustness and avoid randomness, we also perform ten-fold cross-validation (Fig. 6). These accuracy values are comparable to the results from the 8:2 training-validation split, indicating stable predictive capability of the model. It confirms the robustness and generalizability of our soil EC prediction model. Based on these results, the NNF model with an 8:2 sample division, incorporating the effects of soil moisture (PDI), along with the introduction of SIT and TIR, was adopted to estimate soil EC and map saline soils across the study area. These values indicate moderate predictive capability appropriate for regional-scale salinity mapping.

Cross-dataset comparison

To assess the accuracy of our results, we conducted a validation against the National Land Surveys (NLS) carried out between 2007 and 2009 (https://gtdc.mnr.gov.cn/Share#/secondSurvey). Specifically, we compared the total saline soil area for the year 2009 in our study with that reported in the NLS. Our model identified a total saline soil area of 5,068.43 km2, closely aligning with the 5,213.50 km2 reported by the NLS (Table 10), resulting in a marginal difference of only 2.78%.

This high level of agreement highlights the robustness and reliability of our spatiotemporal salinity mapping approach and affirms the model’s capacity to accurately delineate salinized areas at regional scales.

Furthermore, we compared the soil salinity degree with two existing global salinity products—SSSG (https://code.earthengine.google.com/c1b8b3fb1ace888cd7e9846b3e3219ce) and LDSS11 (Fig. 7)—for selected years (seven years of the data). Our estimates of saline area in the Western Songnen Plain were found to fall between the ranges reported by these datasets, supporting credibility while providing higher resolution and temporal frequency.

Uncertainty analysis

To assess the uncertainty of soil EC prediction, we adopted a quantile regression approach that estimates not only the mean prediction but also 0.05 (Q5) and 0.95 (Q95) quartiles for each sample. The 90% Prediction Interval Width (PIW90) was defined as follow equation51:

This interval provides a statistical range within which the true logarithmic EC value (LnEC) is expected to fall with 90% confidence, thus reflecting both model-driven and data-inherent uncertainty.

Figure 8a shown the predicted Q5, Q95, and mean LnEC values in ascending order of the predicted mean. The majority of observed EC values fall within the PIW90, indicating strong reliability and high coverage probability. Notably, the prediction intervals are narrower for moderate to high EC values and broader for low EC values. This pattern aligns with the spectral detectability of saline soils–high EC areas tend to have stronger and more consistent spectral signals, while low EC areas are more susceptible to environmental noise and model uncertainty.

To further validate the spatial relevance of the uncertainty estimates, we mapped the predicted PIW90 alongside the residuals in Fig. 8b. The spatial pattern reveals that larger residuals tend to occur in areas with wider predicted intervals, particularly in low-salinity regions. This spatial congruence supports the validity of our uncertainty estimates and demonstrates that the model effectively characterizes both aleatory uncertainty (data variability) and epistemic uncertainty (model limitations in data-sparse zones).

Limitation and future work

Although this study rigorously selected imagery from the post-harvest bare soil period (i.e., between September harvest and November snowfall), and adjusted the bare-soil timing annually based on phenological cues, it is acknowledged that residual vegetation such as crop straw may persist on the soil surface. These remnants can interfere with reflectance signals and introduce classification uncertainty, particularly in regions with dense agricultural activity. In the saline soil prediction model, we systematically accounted for variations in land cover, soil classification units, and salinity gradients across the western Songnen Plain. However, the eastern and southeastern subregions, were relatively underrepresented in the field sampling. This limited coverage may constrain the model’s ability to learn subtle spatial patterns in these marginal zones.

To address these limitations, future research will focus on two key directions: (1) We will incorporate spectral filtering techniques to more effectively identify and exclude pixels affected by crop residue or early regrowth. This will improve the purity of bare-soil spectral signatures and enhance the quality of input data for both classification and regression tasks52,53. (2) We plan to conduct additional field surveys, with a particular focus on underrepresented subregions and low-salinity transitional zones. This will enhance the spatial representativeness of training data and enable more robust modeling of subtle salinization gradients.

Data availability

The dataset described in this article is publicly available at the Zenodo Repository for A 40-year dataset of soil salinity dynamics (1985–2024) at 100 m resolution in the Western Songnen Plain, China50 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17044260).

Code availability

All source scripts used for saline soil identification model, soil EC prediction model and prediction model input parameters are publicly available on GitHub at https://github.com/mercyxinian/Code.git.

References

Mohamed, S. A. et al. Integrating Active and Passive Remote Sensing Data for Mapping Soil Salinity Using Machine Learning and Feature Selection Approaches in Arid Regions. Remote Sens. 15, 1751 (2023).

Agriculture, I. I. o. T., Land, A. O. o. t. U. N., Service, P. N. M., & Branch, A. O. o. t. U. N. A. E. Manual on integrated soil management and conservation practices (Food & Agriculture Org., 2000).

Shiklomanov, I. A. Assessment of water resources and water availability in the world. Comprehensive Assessment of the Freshwater Re-sources of the World (1997).

Wang, L., Seki, K., Miyazaki, T. & Ishihama, Y. The causes of soil alkalinization in the Songnen Plain of Northeast China. Paddy Water Environ. 7, 259–270 (2009).

Perri, S., Molini, A., Hedin, L. O. & Porporato, A. Contrasting effects of aridity and seasonality on global salinization. Nat. Geosci. 15, 375–381 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Dynamics of saline-alkali land and its ecological regionalization in western Songnen Plain, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 20, 159–166 (2010).

Yu, H. et al. Mapping Soil Salinity/Sodicity by using Landsat OLI Imagery and PLSR Algorithm over Semiarid West Jilin Province, China. Sensors 18, 1048 (2018).

Yu, H. et al. Spatiotemporal variations of soil salinization in China’s West Songnen Plain. Land Degrad. Dev. 34, 2366–2378 (2023).

Ivushkin, K. et al. Global mapping of soil salinity change. Remote Sens. Environ. 231, 111260 (2019).

Hassani, A., Azapagic, A. & Shokri, N. Predicting long-term dynamics of soil salinity and sodicity on a global scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 33017–33027 (2020).

Hassani, A., Azapagic, A. & Shokri, N. Predicting Long-term Dynamics of Soil Salinity and Sodicity on a Global Scale. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13295918.v1 (2020).

Avdan, U. et al. Soil salinity prediction models constructed by different remote sensors. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 128, 103230 (2022).

Sahbeni, G., Ngabire, M., Musyimi, P. K. & Székely, B. Challenges and Opportunities in Remote Sensing for Soil Salinization Mapping and Monitoring: A Review. Remote Sens. 15, 2540 (2023).

Hateffard, F., Steinbuch, L. & Heuvelink, G. B. M. Evaluating the extrapolation potential of random forest digital soil mapping. Geoderma 441, 116740 (2024).

Nie, Y., Tan, Y., Deng, Y. & Yu, J. Suitability Evaluation of Typical Drought Index in Soil Moisture Retrieval and Monitoring Based on Optical Images. Remote Sens. 12, 2587 (2020).

Ghulam, A., Qin, Q. & Zhan, Z. Designing of the perpendicular drought index. Environ Geol. 52, 1045–1052 (2007).

Shahabfar, A., Ghulam, A. & Eitzinger, J. Drought monitoring in Iran using the perpendicular drought indices. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 18, 119–127 (2012).

Wicke, B. et al. The global technical and economic potential of bioenergy from salt-affected soils. Energy & Environmental Science 4, 2669–2681 (2011).

Shen, J., Chen, Y., Wang, Q. & Fu, H. Spatiotemporal Variation in Saline Soil Properties in the Seasonal Frozen Area of Northeast China: A Case Study in Western Jilin Province. Water 15, 1812 (2023).

Yang, J. & Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover datasets and its dynamics in China from 1985 to 2023. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12779975 (2024).

ISRIC, F.-U. FAO-Unesco soil map of the world, Revised Legend. World Soil Resources Report 60 (1990).

Zhang, C. & McGrath, D. Geostatistical and GIS analyses on soil organic carbon concentrations in grassland of southeastern Ireland from two different periods. Geoderma 119, 261–275 (2004).

Zhi, F. et al. Rapid and Automated Mapping of Crop Type in Jilin Province Using Historical Crop Labels and the Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 14, 4028 (2022).

Dong, Y. et al. A 30-m annual corn residue coverage dataset from 2013 to 2021 in Northeast China. Sci. Data 11, 216 (2024).

Stillinger, T., Roberts, D. A., Collar, N. M. & Dozier, J. Cloud Masking for Landsat 8 and MODIS Terra Over Snow-Covered Terrain: Error Analysis and Spectral Similarity Between Snow and Cloud. Water Resources Research 55, 6169–6184 (2019).

Wang, D. et al. Minimizing vegetation influence on soil salinity mapping with novel bare soil pixels from multi-temporal images. Geoderma 439, 116697 (2023).

Feng, G., Masek, J., Schwaller, M. & Hall, F. On the blending of the Landsat and MODIS surface reflectance: predicting daily Landsat surface reflectance. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 44, 2207–2218 (2006).

Skakun, S. et al. Validation of the LaSRC Cloud Detection Algorithm for Landsat 8 Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 12, 2439–2446 (2019).

Helder, D. et al. Absolute Radiometric Calibration of Landsat Using a Pseudo Invariant Calibration Site. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 51, 1360–1369 (2013).

Macfarlane, C., Grigg, A. H. & Daws, M. I. A standardised Landsat time series (1973–2016) of forest leaf area index using pseudoinvariant features and spectral vegetation index isolines and a catchment hydrology application. Remote Sens. Appl.-Soc. Environ. 6, 1–14 (2017).

Flood, N. Continuity of Reflectance Data between Landsat-7 ETM+ and Landsat-8 OLI, for Both Top-of-Atmosphere and Surface Reflectance: A Study in the Australian Landscape. Remote Sens. 6, 7952–7970 (2014).

Yeh, C. et al. Using publicly available satellite imagery and deep learning to understand economic well-being in Africa. Nat. Commun. 11, 2583 (2020).

Zhu, Z. Change detection using landsat time series: A review of frequencies, preprocessing, algorithms, and applications. ISPRS-J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 130, 370–384 (2017).

Belgiu, M. & Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS-J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 114, 24–31 (2016).

Tan, J. et al. Estimating soil salinity in mulched cotton fields using UAV-based hyperspectral remote sensing and a Seagull Optimization Algorithm-Enhanced Random Forest Model. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 221, 109017 (2024).

Cunningham, P. & Delany, S. J. k-Nearest Neighbour Classifiers - A Tutorial. ACM Comput. Surv. 54, 1–25 (2021).

Rigatti, S. J. Random Forest. Journal of Insurance Medicine 47, 31–39 (2017).

Hollmann, N. et al. Accurate predictions on small data with a tabular foundation model. Nature 637, 319–326 (2025).

Khan, N. M., Rastoskuev, V. V., Sato, Y. & Shiozawa, S. Assessment of hydrosaline land degradation by using a simple approach of remote sensing indicators. Agricultural Water Management 77, 96–109 (2005).

Allbed, A., Kumar, L. & Aldakheel, Y. Y. Assessing soil salinity using soil salinity and vegetation indices derived from IKONOS high-spatial resolution imageries: Applications in a date palm dominated region. Geoderma 230-231, 1–8 (2014).

Elhag, M. & Bahrawi, J. A. Soil salinity mapping and hydrological drought indices assessment in arid environments based on remote sensing techniques. Geosci. Instrum. Methods Data Syst. 6, 149–158 (2017).

Hoa, P. V. et al. Soil Salinity Mapping Using SAR Sentinel-1 Data and Advanced Machine Learning Algorithms: A Case Study at Ben Tre Province of the Mekong River Delta (Vietnam). Remote Sens. 11, 128 (2019).

Habibi, V., Ahmadi, H., Jafari, M. & Moeini, A. Mapping soil salinity using a combined spectral and topographical indices with artificial neural network. PloS One 16, e0228494 (2021).

Pasolli, L., Melgani, F. & Blanzieri, E. Gaussian Process Regression for Estimating Chlorophyll Concentration in Subsurface Waters From Remote Sensing Data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 7, 464–468 (2010).

Allegrini, F. & Olivieri, A. C. Two sides of the same coin: Kernel partial least-squares (KPLS) for linear and non-linear multivariate calibration. A tutorial. Talanta Open 7, 100235 (2023).

Wang, G. & Jiao, J. A Kernel Least Squares Based Approach for Nonlinear Quality-Related Fault Detection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 64, 3195–3204 (2017).

Kim, K., Lee, J.-M. & Lee, I.-B. A novel multivariate regression approach based on kernel partial least squares with orthogonal signal correction. Chemometrics Intell. Lab. Syst. 79, 22–30 (2005).

Chi, C. & Wang, Z. Conversion relationships between the chemical parameters in saturated and in 1∶5 soil/water extracts of saline and alkaline soils in Songnen Plain of Northeast China. Chinese Journal of Ecology 28, 172–176 (2009).

Kong, F. et al. Spatio-temporal evolution of water erosion in the western Songnen Plain: Analysis of its response to land use dynamics and climate change. Soil Tillage Res. 245, 106299 (2025).

Wang, B., Li, X. & Gao, Z. A. 40-year dataset of soil salinity dynamics (1985–2024) at 100 m resolution in the Western Songnen Plain, China. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17044260 (2025).

Lilburne, L., Helfenstein, A., Heuvelink, G. B. M. & Eger, A. Interpreting and evaluating digital soil mapping prediction uncertainty: A case study using texture from SoilGrids. Geoderma 450, 117052 (2024).

Liang, Z. et al. Evaluating Maize Residue Cover Using Machine Learning and Remote Sensing in the Meadow Soil Region of Northeast China. Remote Sens. 16, 3953 (2024).

Zhang, Y. & Du, J. Improving maize residue cover estimation with the combined use of optical and SAR remote sensing images. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 12, 578–588 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research received financial support by National Key Research and Development Program (No. 2022YFD1500505) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province (No. YDZJ202201ZYTS550). This research is an output of Cropland Degradation Monitoring. We greatly acknowledge the free access to the Landsat data provided by the USGS, land cover data provided by Wuhan University, all data providers that have been used in this study, and the Google Earth Engine platform.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L.: conceptualization, methodology, software, supervision, writing – review & editing; B.W.: data curation, software, writing – original draft; Z.G. and Z.L.: visualization, investigation, validation; Z.J. and Z.L.: writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, B., Li, X., Gao, Z. et al. A 40-year dataset of soil salinity dynamics (1985–2024) at 100 m resolution in the Western Songnen Plain, China. Sci Data 12, 1783 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06057-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06057-7

Statistical_results_by_year/

Statistical_results_by_year/ Salinity_degree_maps/

Salinity_degree_maps/ Saline_soil_identification/

Saline_soil_identification/