Abstract

As members of the Tenuipalpidae family, Brevipalpus mites have emerged as significant research subjects in agriculture and horticulture due to their polyphagous nature, high reproductive potential, and ability to transmit plant viruses. However, the evolutionary understanding of this taxon remains constrained by the absence of high-quality chromosomal genome data. In this study, we present the first chromosome-level genome assembly of B. obovatus, achieved through an integrative approach utilizing Illumina, Nanopore, PacBio, and Hi-C sequencing technologies. The final genome assembly comprises 67.28 Mb in length with contig and scaffold N50 values of 33.74 Mb and 33.74 Mb, respectively. The chromosome-scale assembly (five contigs anchored to two chromosomes) showed 87.4% BUSCO completeness (arachnida_odb12, n = 1,123). We annotated 9,193 protein-coding genes (89.1% BUSCO completeness), including 8,756 functionally annotated genes, and identified repetitive sequences accounting for 12.2%. This genome provides a valuable resource for advancing the understanding of flat mite genetics and evolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Flat mites, commonly known as false spider mites, are a group of phytophagous mites widely distributed in the family Tenuipalpidae (Acari: Prostigmata), many of which are economically significant agricultural pests1. This family comprises over 1,100 described species, with Brevipalpus being the most economically impactful genus, accounting for 90% of crop damage reports within this group2,3. Their global distribution spans tropical and subtropical agroecosystems, where they exploit >1,200 host plant species, including economically important crops like coffee, ornamentals, and fruit trees4,5. Among these, B. obovatus is a representative and critical species within the family. This pest species causes significant damage to multiple economically important crops (e.g., citrus, tea, and grapevines) and serves as a competent vector for transmitting various plant viruses, including both cytoplasmic and nuclear types (notably Citrus leprosis virus). Its expanding threat to global fruit production and horticultural systems underscores the urgent need for effective management strategies6,7,8. Recent studies indicate that B. obovatus-transmitted Citrus leprosis virus C (CiLV-C) can lead to citrus yield losses of up to 80%, while increasing control costs by over 30%8. Furthermore, the expansion of this mite in tropical regions has significantly accelerated due to climate change9. Due to its minute body size, rapid reproduction, and strong morphological similarities, traditional taxonomic and control methods face significant limitations10,11. Additionally, biological aspects such as its virus transmission mechanisms, host adaptability, and resistance evolution remain poorly understood, necessitating systematic analysis at the genomic level12.

Despite the considerable agricultural impact of some Tenuipalpidae species, their genomic data are still highly deficient. Currently, the sole available genome is a draft assembly of B. yothersi (71.18 Mb, comprising 849 scaffolds with an N50 of 632 kb)13. This limitation has constrained research into their molecular biological traits. Previous cytogenetic studies have revealed that species within the Tenuipalpidae family typically exhibit an exceptionally low chromosome number, with most species in the Brevipalpus possessing only two chromosomes, ranking among the lowest known chromosome counts in arthropods14,15. To facilitate deeper insights into this group, we assembled a chromosome-scale reference genome for B. obovatus – one of the most damaging species in this family. This genome provides a critical genome resource for exploring the interaction mechanisms between B. obovatus and viruses, the genetic basis of host adaptation, its sex determination system, and potential control targets16. It also lays a solid foundation for subsequent comparative genomics, population genetic analyses, and the development of precise monitoring and control technologies.

Within this research, we resolved the B. obovatus genome using a hybrid approach: Nanopore/PacBio long-read scaffolding polished with Illumina data (including genome survey, Hi-C, RNA-seq). The final sequences were completely anchored to two chromosomes, yielding a high-quality nuclear genome assembly. Furthermore, we performed comprehensive multi-level genome annotation. This chromosome-level assembly provides an essential genomic foundation for elucidating the evolutionary biology of flat mites (Tenuipalpidae) and enables comparative studies across Acari.

Methods

Sample collection and laboratory colony establishment

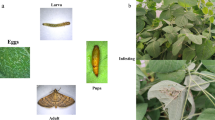

B. obovatus was originally collected from South Campus of Guizhou University, Guizhou Province, China (106°40′6.1″ E; 26°25′44″N; 1084.9 m a.s.l.), 10 October, 2022, by Hu-Die He, and subsequently identified based on morphological characteristics17, with supporting ecological photographs and scanning electron micrographs provided (Fig. 1). To minimize heterozygosity effects, a laboratory colony was established from a single gravid female. This colony was maintained on potted Alocasia macrorrhizos (Monocotyledons, Araceae) plants (common name: Giant Taro), with a population size of several thousand individuals, and was continuously reared for at least 30 generations under controlled conditions of 26 ± 2 °C, 70 ± 5% relative humidity, and a photoperiod of L16:D8.

DNA and RNA sequencing

Total genomic DNA and RNA were extracted from over 80,000 eggs. Genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method and RNA was extracted from the blood according to the instruction of PAXgene Blood RNA Kit (QIAGEN, 762174). For genome survey analysis, standard whole-genome sequencing libraries (350 bp inserts, 150 bp paired-end) were constructed with the TruSeq DNA PCR-Free kit and sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq X Plus platform. Following successful genome survey analysis, a PacBio 20 kb SMRTbell library was constructed using the SMRTbell® Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, Cat. #PN 101-853-100, Menlo Park, CA, USA) with more than 5 μg of genomic DNA (gDNA). Briefly, DNA was sheared to an average size of 20 kb using a Megaruptor system (Diagenode B06010001, Liege, Belgium), followed by end-repair, adapter ligation, and size selection with BluePippin (Sage Science BLU0001, USA; cutoff: 20 kb). Libraries were sequenced on an 8 M single-molecule real-time (SMRT) cell using the PacBio Revio platform (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). To anchor contigs into chromosome-scale scaffolds, we employed high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) sequencing technology. The experimental procedure was conducted as follows: First, chromatin was crosslinked with formaldehyde and digested with HindIII restriction enzyme, followed by proximity ligation to capture three-dimensional genomic interactions. After DNA purification, libraries with insert sizes of 300–700 bp were size-selected and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq X Plus platform. all libraries preparation and sequencing operations performed by Berry Genomics (Beijing, China). To obtain improved annotation accuracy, Synthesis of cDNA for sequencing was performed using the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module for RNA enrichment, and the ONT PromethION library was constructed with the SQK-PCS109 + SQKPBK004 kit. The library construction was completed by BenaGen (Wuhan, China). RNA isolation was performed with TRIzol™ Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and poly(A)-enriched libraries were constructed using the VAHTS mRNA-seq v2 Library Prep Kit (Vazyme, NR603) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Paired-end sequencing (150 bp) was conducted on the Illumina NovaSeq XPlus platform at Berry Genomics (Beijing, China). A total of 41.7 Gb of raw sequencing data was generated from the analysis. The quantity of raw sequences generated and the sequencing depth are detailed in Table 1.

Genome survey

First, fastp v0.23.218 was used to perform quality control and trimming on the obtained Illumina data with the following parameters: retain sites with a base quality score of no less than 20 ( >Q20), remove duplicate sequences (-D), trim poly-G/X tails (-g -x), ensure that the proportion of unqualified bases does not exceed 10% (-u 10), and correct bases using overlapping reads (-c).

The survey was inferred based on Short-reads data and the k-mer frequency distribution, with k-mer frequencies evaluated using jellyfish global 119 and the sequence length set to 21 k-mer (ploidy = 1). GenomeScope v2.020 was employed for genome feature analysis, with the maximum k-mer depth threshold set to 10,000 and parameters specified as ‘-k 21 -p 1 -m 10,000’. The results indicated that the predicted genome size was 60.52 Mb. Detailed results are shown in (Fig. 2).

Genome assembly

High-quality HiFi reads were initially assembled using Hifiasm v0.25.0-r72621 with default parameters, and only contigs with sequencing depth exceeding 10X were retained in the Hifiasm assembly to exclude low-depth sequences that are likely contaminants or errors. The Hifiasm assembly, based on both second-generation and third-generation data, was polished using nextPolish v1.4.122. Redundant sequences in the polished results were removed using Purge_dups v1.2.523, which operates based on contig similarity and sequencing depth. Minimap2 v2.24-r112224 was selected as the sequence alignment tool to align HiFi reads to the genome (‘-cx map-hifi’) and for self-alignment of the genome (‘-x asm5 -DP’). Purge_dups was run with default parameters (‘-2 -a 70’).

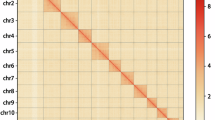

Hi-C data and the YAHS v1.225 workflow were utilized for chromosome scaffolding and assembly of contigs. First, chromap v0.3.0-r50926 was used to perform quality control on the Hi-C data, including read alignment, duplicate removal, and Hi-C contact extraction. Then, two rounds of scaffolding were conducted using YAHS v1.2 with default parameters. After the initial round of scaffolding, the assembly was manually corrected using Juicebox v1.11.0827, followed by a second round of final scaffolding. The sequencing depth of the final genome was evaluated using SAMtools v1.16.128, with the input aligned BAM files generated by minimap2 based on HIFI (‘-ax map-hifi’) or second-generation WGS (‘-ax sr’) reads. As shown in the Hi-C scaffolding heatmap (Fig. 3), the excellent quality of chromosome scaffolding is evident, which resulted in the assembly of two chromosomes.

Genome completeness was assessed using BUSCO v5.8.329 based on the arachnida_odb12 reference database (n = 1,123 single-copy orthologous genes), which predicts the integrity of existing genes in the genome using near-universal single-copy orthologous genes (USCO) from Arachnida. Meanwhile, the utilization rate of raw data and the integrity of the assembly were examined by aligning second-generation and third-generation genomic raw sequences to the genome assembly. The alignment tools used was Minimap2, with alignment rates calculated by SAMtools28. Possible contamination in the assembly was identified using MMseq. 2 v1330 for a blastn-like search, with the NCBI nt_pork and UniVec databases as references. Single-base quality scores (QV values) and genome k-mer spectra were evaluated using merqury v1.431. In addition, the genomic data of Brevipalpus yothersi was downloaded for completeness assessment, and the results showed that the two species have similar completeness and GC content. Detailed metrics of the final genome assembly are shown in Table 2.

Genome annotation

The RepeatModeler v2.0.432 software was used, with the additional LTR search process enabled (‘-LTRStruct’), to construct a species-specific repeat library based on the specific structure of repetitive sequences and de novo prediction principles. This library was then merged with the Dfam 3.733 and RepBase-2018102634 databases to form the final reference database for repetitive sequences. Repeat sequence prediction was performed using RepeatMasker v4.1.535 and the final constructed repeat database for alignment and identification. The results revealed that repetitive sequences accounted for 8,207,062 bp, representing 12.2% of the genome. The top five categories of repetitive sequences in the B. obovatus genome were: LTRs (1.93%), Unknown (1.73%), DNA (1.35%), SINEs (0.28%) and LINEs (0.21%). The statistical results are shown in Table 3.

Annotation of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) was performed using two strategies: (1) Alignment with known non-coding RNA libraries (Rfam database) for the annotation of rRNA, snRNA, and miRNA, utilizing the Infernal v1.1.536 software; (2) Prediction of tRNA sequences in the genome using the tRNAscan-SE v2.0.1237 software. The annotation results identified a total of 234 ncRNAs, including 107 rRNAs, 75 tRNAs, 26 miRNAs, 17 snRNAs, and 9 ribozymes.

Protein-coding gene structure annotation was performed using the MAKER v3.01.0438 pipeline, integrating three types of evidence to predict protein-coding gene structures. The specific workflow included: (1) Ab initio gene prediction: BRAKER v3.0.339 and GeMoMa v1.940 were employed, incorporating transcriptomic and protein evidence to expand the pool of potential coding gene candidates. Transcriptomic data were generated by aligning RNA-Seq second-generation transcriptome data to the genome using HISAT2 v2.2.141 to produce BAM alignment files; (2) Gene structure prediction via transcript alignment: StringTie v2.2.142 was used for reference-based assembly of second-generation transcriptome data, with short-sequence BAM alignment files generated in step (1) as input; (3) Homology-based prediction: Homology comparisons were conducted with known protein sequences from five homologous species: Dermatophagoide farinae (RefSeq: GCF_020809275.1), Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (RefSeq: GCF_001901225.1), Panonychus citri (RefSeq: GCF_014898815.1), Tetranychus urticae (RefSeq: GCF_000239435.1) and Oppia nitens (RefSeq: GCF_028296485.1). Protein sequences were analyzed using GeMoMa as described above. Detailed results of coding genes are shown in Table 4. A total of 9,139 protein-coding genes were predicted by the MAKER pipeline, with a total length of 4,790,788 bp and an average amino acid length of 521.1 bp. BUSCO assessment of the predicted protein-coding gene sequences showed completeness rates as follows: C: 89.1% [S: 87.2%, D: 2.0%], with F: 3.7% fragmented and M: 7.2% missing genes, based on n = 1,123 core orthologs analyzed.

Gene function annotation was conducted through sequence alignment to established databases, such as UniProtKB v202504 (including SwissProt and TrEMBL). The alignment was conducted using Diamond v2.1.843 to search the UniProtKB database for gene function information. Next, InterPro 5.74-105.06444 was used to search the Pfam45 database. Finally, more protein sequences were functionally annotated by searching the eggNOG v5.0.246 evolutionary genealogy of genes database using eggNOG-mapper v2.1.1247 with default parameters. The results showed that the four databases identified 7,532, 8,571, 6,562, and 8,181 functional genes, respectively. After removing duplicates, a total of 8,756 genes were obtained, among which 6,494 were present in all four databases. The outcomes are tabulated and graphically represented in Table 4 and Fig. 4.

Data Records

The raw reads and genome assembly have been submitted to the NCBI database under BioProject PRJNA125796948, with WGS, Hifi, Hi-C, ONT, and RNA-seq accession numbers SRP58750849. The complete genome assembly is publicly accessible through NCBI under accession number GCA_050580445.150. The genome assembly and annotation files are available in Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29252108)51.

Technical Validation

Genome assembly quality of B. obovatus was evaluated using two approaches. Firstly completeness assessment via BUSCO v5.8.3 using the “arachnida_odb12” database (n = 1,123), showing 87.4% total completeness (85.5% single-copy, 2.0% duplicated BUSCOs) for the genome; subsequently, we assessed base-level accuracy using Merqury v1.4, obtaining a single-base quality value (QV) of 71.4. We found that the majority (99.83%) of the assembled genome is contained within the two largest scaffolded chromosomes confirmed by Hi-C analysis. These metrics collectively demonstrate that the assembly has achieved exceptional standards in both contiguity and completeness. Additionally, the completeness assessment of protein-coding gene prediction yielded a result of 89.1% (87.2 single-copy, 2.0% duplicated BUSCOs). Collectively, these assessments demonstrate the high quality of both the genome assembly and annotation.

Code availability

No custom scripts were employed in this study. All data processing followed standardized pipelines using the bioinformatics tools detailed in the Methods section.

Data availability

These data have not been previously published. The raw sequencing reads and the assembled genome for this species have been deposited in the NCBI database under BioProject accession number PRJNA1257969. Additionally, the genome annotation files are available on Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29252108).

References

Childers, C., Frenc, J. V. & Rodrigues, J. V. Brevipalpus californicus, B. obovatus, B. phoenicis, and B. lewisi (Acari: Tenuipalpidae): a review of their biology, feeding injury and economic importance. Exp Appl Acarol. 30, 5–28 (2003).

Castro, E. B. et al. A newly available database of an important family of phytophagous mites: Tenuipalpidae Database. Zootaxa. 4868(4), 577–583 (2020).

He, H. D., Jin, D. C., Ochoa, R. & Yi, T. C. A new species of Ultratenuipalpus and redescription of Ultratenuipalpus hainanensis (Wang) (Acari, Tenuipalpidae). Zootaxa 5485(1), 201–225 (2024).

Avijit, R., Jonathan, S., Guillermo, L., Gabriel, O. C. & Ronald, O. Role bending: complex relationships between viruses, hosts, and vectors related to citrus leprosis, an emerging disease. Phytopathology 105(7), 1013–1025 (2015).

Beard, J. J., Ochoa, R., Braswell, W. E. & Bauchan, G. R. Brevipalpus phoenicis (Geijskes) species complex (Acari: Tenuipalpidae)—a closer look. Zootaxa 3944, 1–67 (2015).

Rodrigues, V. et al. Não-transmissão de isolado brasileiro do vírus da leprose dos citros por Brevipalpus obovatus. Summa Phytopathologica 31(1), 64 (2005).

Ferreira, P. D. T. O. et al. Characterization of a bacilliform virus isolated from Solanum violaefolium transmitted by the tenuipalpid mites Brevipalpus phoenicis and Brevipalpus obovatus. Summa Phytopathologica 33, 264–269 (2007).

Bastianel, M. et al. Citrus leprosis: Centennial of an unusual mite–virus pathosystem. Plant Dis. 94(3), 284–292 (2010).

Bastianel, M. et al. Climate change effects on the worldwide distribution of Brevipalpus californicus and Brevipalpus yothersi. J Asia Pac Entomol. 27(4), 102333 (2024).

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Pest risk assessment made by France on Brevipalpus californicus, Brevipalpus phoenicis and Brevipalpus obovatus (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) considered by France as harmful in the French overseas departments of Guadeloupe and Martinique‐Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Plant Health. EFSA J. 6(5), 678 (2008).

Rodrigues, J. C. & Childers, C. C. Brevipalpus mites (Acari: Tenuipalpidae): vectors of invasive, non-systemic cytoplasmic and nuclear viruses in plants. Exp Appl Acarol. 59, 165–175 (2013).

Tassi, A. D., Ramos-González, P. L., Sinico, T. E., Kitajima, E. W. & Freitas-Astúa, J. Circulative transmission of cileviruses in Brevipalpus mites may involve the paracellular movement of virions. Front Microbiol. 13, 836743 (2022).

Navia, D. et al. Draft genome assembly of the false spider mite Brevipalpus yothersi. Microbiol Resour Announc. 8(6), 10–1128 (2019).

Helle, W., Bolland, H. R. & Heitmans, W. R. B. Chromosomes and types of parthenogenesis in the false spider mites (Acari: Tenuipalpidae). Genetica. 54, 45–50 (1980).

Pijnacker, L. P., Ferwerda, M. A., Bolland, H. R. & Helle, W. Haploid female parthenogenesis in the false spider mite Brevipalpus obovatus (Acari: Tenuipalpidae). Genetica 51, 211–214 (1981).

Grbić, M. et al. The genome of Tetranychus urticae reveals herbivorous pest adaptations. Nature 479(7374), 487–492 (2011).

Baker, E. W. The genus Brevipalpus (Acarina: Pseudoleptidae). Am Midl Nat. 42(2), 350–402 (1949).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Lee, S. H. et al. The global spread of jellyfish hazards mirrors the pace of human imprint in the marine environment. Environ Int. 171, 107699 (2023).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun. 11, 1432 (2020).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature Methods. 18, 170–175 (2021).

Hu, J. et al. NextPolish2: A Repeat-aware Polishing Tool for Genomes Assembled Using HiFi Long Reads. Geno Proteom Bioinf. 22 (2024).

Guan, D. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 36, 2896–2898 (2020).

Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Zhou, C., McCarthy, S. A. & Durbin, R. YaHS: Yet another Hi-C scaffolding tool. Bioinformatics 39, btac808 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Fast alignment and preprocessing of chromatin profiles with Chromap. Nat Commun. 12(1), 6566 (2021).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 10, giab008 (2021).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simão, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 38, 4647–4654 (2021).

Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. MMseqs. 2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat Biotechnol. 35, 1026–1028 (2017).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: Reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 21, 245 (2020).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Storer, J., Hubley, R., Rosen, J., Wheeler, T. J. & Smit, A. F. The Dfam community resource of transposable element families, sequence models, and genome annotations. Mob DNA 12, 2 (2021).

Bao, W., Kojima, K. K. & Kohany, O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob DNA 6, 11 (2015).

Smit, A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker Open-4.0. http://www.repeatmasker.org (2013/2015).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

Chan, P. P. & Lowe, T. M. TRNAscan-SE: Searching for tRNA genes in genomic sequences. Methods Mol Biol. 1962, 1–14 (2019).

Holt, C. & Yandell, M. MAKER2: An annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 491 (2011).

Gabriel, L. et al. BRAKER3: Fully automated genome annotation using RNA-seq and protein evidence with GeneMark-ETP, AUGUSTUS, and TSEBRA. Genome Research 34(5), 769–777 (2024).

Keilwagen, J., Hartung, F., Paulini, M., Twardziok, S. O. & Grau, J. Combining RNA-seq data and homology-based gene prediction for plants, animals and fungi. BMC Bioinformatics. 19 (2018).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol 37, 907–915 (2019).

Kovaka, S. et al. Transcriptome assembly from long-read RNA-seq alignments with StringTie2. Genome Biol. 20, 278 (2019).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H.-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 18, 366–368 (2021).

Finn, R. D. et al. InterPro in 2017—Beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D190–D199 (2017).

El-Gebali, S. et al. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D427–D432 (2019).

Cantalapiedra, C. P., Hernández-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P. & Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol Biol Evol. 38, 5825–5829 (2021).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. eggNOG 5.0: A hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D309–D314 (2019).

NCBI BioProject https://identifiers.org/ncbi/bioproject:PRJNA1257969 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP587508 (2025).

NCBI Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_050580445.1 (2025).

He, H. D. et al. Genome Assembly and Annotation of Brevipalpus obovatus (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29252108) (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.32160118 and 32470478), and the National Science and Technology Basic Resources Survey Special Project (Grant No. 2022FY202100). We sincerely thank Prof. Feng Zhang from Nanjing Agricultural University for his valuable technical guidance and constructive suggestions on manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tian-Ci Yi and Dao-Chao Jin provided financial support and technical guidance. Hu-Die He participated in the collection and preparation of samples, as well as the writing and revision of the manuscript. Lang Liang completed the data analysis. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, HD., Liang, L., Jin, DC. et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the flat mite Brevipalpus obovatus. Sci Data 12, 1779 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06061-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06061-x