Abstract

Inelastic neutron scattering (INS) provides direct insights into microscopic magnetic interactions in crystalline materials, making it a valuable experimental technique in condensed matter physics and materials science. These interactions can be extracted by fitting spin wave dispersions to Heisenberg Hamiltonians using spin wave theory. However, such datasets are scattered across the literature and lack a standardized format, which limits their accessibility, reproducibility, and utility. In this work, we compile and standardize exchange interaction data obtained from INS experiments on nearly 100 magnetic materials. The resulting dataset includes exchange parameters expressed in a unified Heisenberg model format, visualizations of crystal structures with annotated exchange pathways, and Monte Carlo simulation files generated using the ESpinS code. We use these experimentally derived exchange interactions to compute magnetic transition temperatures (Tc) via classical Monte Carlo simulations. Furthermore, we examine the impact of the (S + 1)/S correction in the simulations and find it improves agreement with experimental Tc values in most cases. All data and related resources are openly available through a public GitHub repository.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inelastic neutron scattering (INS) is a powerful technique for probing magnetic excitations, such as magnons-quasiparticles that represent collective spin-wave excitations in a lattice1,2,3. By measuring the energy and momentum transferred during neutron scattering events, INS provides direct insight into magnon dispersion relations. These dispersions are highly sensitive to the underlying magnetic exchange interactions, making INS an invaluable tool for characterizing magnetic systems.

Magnetic interactions in a material can be extracted by analyzing magnon excitation data through spin-wave theory, which models magnetic excitations based on an effective spin Hamiltonian1,4. However, employing full quantum spin operators in such Hamiltonians introduces significant theoretical and computational complexity. To overcome this challenge, linear spin-wave theory (LSWT) serves as a widely used approximation method1,5,6. LSWT simplifies the problem by linearizing quantum fluctuations around an ordered magnetic ground state, expressing spin operators in terms of bosonic creation and annihilation operators. This reduces the Hamiltonian to a quadratic form, enabling an analytical solution. For example, in a simple antiferromagnetic system with only nearest-neighbor interactions, the spin Hamiltonian is given by: \({\mathcal{H}}=-{\sum }_{\langle i,j\rangle }J\,{{\bf{S}}}_{i}\cdot {{\bf{S}}}_{j}\) where J is the exchange interaction, and the summation ⟨i, j⟩ runs over nearest-neighbor spin pairs. Within LSWT, the magnon dispersion relation for this model simplifies to: \(E({\bf{k}})=-JZS\sqrt{1-{\gamma }_{{\bf{k}}}^{2}}\) where Z is the coordination number (i.e., the number of nearest neighbors), and γk is a geometric structure factor defined as: \({\gamma }_{{\bf{k}}}=\frac{1}{Z}{\sum }_{{\boldsymbol{\delta }}}{e}^{i{\bf{k}}\cdot {\boldsymbol{\delta }}}\). Here, δ represents the displacement vectors connecting a reference site to its nearest neighbors6.

Despite the availability of theoretical frameworks such as LSWT for analyzing INS data, the number of reported exchange interactions derived from INS remains limited. This is due to the specialized instrumentation, high-quality large single crystals, and significant beam time required1,2,3, making INS far less common than elastic neutron diffraction for determining magnetic structures7,8,9. Our literature survey identified only about 100 studies that report both magnon spectra from INS and corresponding spin-model parameterizations using LSWT. Establishing a unified and standardized database for such results would be a valuable resource for the magnetism community, complementing existing magnetic structure repositories.

Such a dataset could serve as a foundation for integrating future high-quality INS results and support systematic theoretical studies aimed at improving computational methods and predictive models. Additionally, establishing validation criteria is essential, as discrepancies often arise between studies on the same material, or even within a single study where multiple spin models are proposed. A fast, reliable theoretical approach such as classical Monte Carlo (MC)10 to evaluate model accuracy would greatly assist in identifying the most appropriate spin Hamiltonian

When spin-wave experimental values for Heisenberg exchange interactions are directly applied in classical MC simulations, the resulting transition temperatures Tc often deviate from expectations. These discrepancies stem from the quantum effects accounted for in spin-wave theory, which are integral to deriving Heisenberg exchange parameters from neutron scattering experiments. To reconcile this mismatch in classical MC simulations, the (S + 1)/S correction, where S is the spin magnitude of magnetic atoms (spin quantum number), has been proposed-either directly to the exchange parameters or indirectly to the Tc values obtained from the simulations11,12,13. In a previous study11, we used Heisenberg exchange interactions derived from INS data for 13 magnetic materials to predict their transition temperatures using classical MC simulations. By applying the (S + 1)/S correction to the MC results, we achieved a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 8% in the predicted transition temperatures.

Building on our previous findings, this work aims to systematically assess the influence of the (S + 1)/S correction on magnetic transition temperatures across a broader range of materials. We extend our dataset to encompass 72 inelastic neutron scattering (INS) studies, ensuring that all extracted exchange parameters are standardized within a consistent spin model Hamiltonian. Using classical MC simulations, we compute transition temperatures both with and without the correction. Our analysis confirms that incorporating the (S + 1)/S factor significantly improves the agreement between simulated and experimental Tc values. To support further research and reproducibility, the complete dataset has been made publicly available on GitHub14. The data is openly accessible and can be freely forked, extended, or updated with new contributions. In addition, for long-term preservation and citability, the dataset has been archived in the Zenodo repository15.

The paper is organized as follows: the Methods section describes the procedures for data collection, standardization, and visualization, as well as the implementation of classical Monte Carlo (MC) simulations. The Data Records section presents the structure and content of the compiled datasets. The Technical Validation section demonstrates the reliability of the data by predicting magnetic transition temperatures, refining spin Hamiltonians using MC results, and comparing the findings with theoretical expectations.

Methods

Data gathering and standardizing

We attempted to identify as many research papers as possible that present INS data (magnetic excitations) analyzed using spin wave theory to extract exchange interactions. A review of the literature shows that the Heisenberg term in spin model Hamiltonians typically appears in one of the following forms:

One of the key challenges in standardizing exchange interactions is the ambiguity in the choice of spin Hamiltonian conventions, particularly regarding the double counting of pairwise interactions. For example, models that use \(-\frac{1}{2}{\sum }_{i,j}{J}_{i,j}\,{{\bf{S}}}_{i}\cdot {{\bf{S}}}_{j}\) or − ∑⟨i, j⟩Ji,j Si ⋅ Sj are designed so that each interaction between spins at sites i and j is counted only once. In contrast, models that adopt − ∑i,jJi,j Si ⋅ Sj or − 2∑⟨i, j⟩Ji,j Si ⋅ Sj count each pairwise interaction twice. A major source of confusion arises when some studies claim to use the convention − ∑i,jJi,j Si ⋅ Sj, yet a detailed analysis-often involving comparisons with other works-reveals that their reported exchange constants have already been corrected to avoid double counting. In practice, these studies effectively use the convention \(-\frac{1}{2}{\sum }_{i,j}{J}_{i,j}\,{{\bf{S}}}_{i}\cdot {{\bf{S}}}_{j}\), as seen, for example, in Refs. 3,16,17,18,19.

A particularly clear example of this mismatch between the stated Hamiltonian and the magnon dispersion derived from spin wave theory is found in the altermagnet MnF23,19. This compound has been extensively studied in INS experiments19,20,21,22 and is widely regarded as a textbook prototype of antiferromagnetic order3,23,24.

Additionally, some papers use a positive sign in front of the summation instead of a negative one. In such cases, the interpretation of Ji,j is reversed: a negative value of Ji,j indicates a ferromagnetic interaction, while a positive value corresponds to an antiferromagnetic interaction.

For magnetic anisotropy, the following forms are commonly considered in the literature:

where D, Dx, and Dz represent the anisotropy strengths along specific directions.

To ensure consistency, we express the exchange and magnetic anisotropy interactions in the following standardized form:

Here, \({\widetilde{J}}_{ij}\) (obtained by rescaling Jij by S2) represents the Heisenberg exchange interaction strength between sites i and j, while \({\widehat{{\bf{S}}}}_{i}\) and \({\widehat{{\bf{S}}}}_{j}\) denote unit vectors indicating the magnetic moment direction at lattice sites i and j. The matrix \(\widetilde{{\bf{A}}}\) characterizes the anisotropy.

To avoid additional complexity, we do not consider the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI) in this work. Therefore, we select data where DMI is either not reported or is negligible compared to the dominant Heisenberg exchange interaction.

Standardization also requires knowledge of the spin quantum number S, as it is necessary for rescaling Jij to \({\widetilde{J}}_{ij}\). Consequently, we exclude studies where the value of S is ambiguous. When available, we adopt the value of S reported in INS studies, as it is typically consistent with the experimentally measured magnetic moment.

In the literature, interaction strengths are expressed in various units, including THz, meV, Kelvin, and cm−1. More recent studies tend to report magnetic interactions in meV. Therefore, we standardize all interaction strengths in meV for consistency.

Visualization and MC simulations

For each compound, provide an image of the crystal structure including illustration for Ji,j between first, second,.., nth nearest neighbors of magnetic atoms indicating by J1, J2 and Jn respectively (Fig. 1). In some papers, researchers prefer to indicate Heisenberg interactions Ji,j by indices of lattice vectors (e.g, Jc indicates exchange interaction between magnetic atoms along lattice c axis). In such cases, we indicate our standard naming of exchange interactions inside parentheses (Fig. 1).

Illustrative images of sample crystal structures from our database. Each image highlights the exchange interactions and their labeling, as presented in the corresponding INS paper. The labels in parentheses indicate the ranking of exchange interactions based on nearest-neighbor distances (e.g., J1 corresponds to the first nearest neighbor,J2 to the second nearest neighbor, and so on).

We use VESTA25 for structure visualization. For each compound, we provide structure files in VESTA format, which not only allow researchers to visualize the atomic positions and lattice vectors but also highlight Heisenberg exchange interactions using thick red lines.

We use the ESpinS26 code for MC simulations. For each compound, we provide all the necessary input and output files for ESpinS code14. Our simulations indicate that using approximately 2000 lattice sites is generally sufficient to predict the transition temperature. Therefore, for MC simulations, we use supercells that contain a minimum of 2000 sites. To determine the transition temperature, we identify the peak of the magnetic specific heat, given by \({C}_{M}=\frac{\left\langle {E}^{2}\right\rangle -{\left\langle E\right\rangle }^{2}}{N{k}_{B}{T}^{2}}\). In cases where the exact peak position is unclear, we also analyze the fourth-order energy cumulant, defined as \({U}_{E}=1-\frac{1}{3}\frac{\left\langle {E}^{4}\right\rangle }{{\left\langle {E}^{2}\right\rangle }^{2}}\).

Data Records

The dataset generated in this work is available on GitHub14 and in the Zenodo repository15. The dataset was compiled from published articles. All sources are fully cited in the Supplementary information and in the repositories, and each data entry includes a reference to its original publication to ensure full traceability.

For each material in the database, there is a dedicated directory named after the compound. Each directory contains the following information:

-

Structure file: A VESTA format file with thick lines indicating exchange interactions.

-

Visualization: A JPEG image showing atomic positions and exchange interactions, as depicted in Fig. 1. This image is displayed online for each compound.

-

Data tables: Tables listing exchange interactions (in meV), spin quantum number S, and both experimental and MC transition temperatures.

-

Reference links: Sources for INS data and transition temperature values.

-

MC simulation files: A MC directory containing all input and output files from MC simulations performed using ESpinS.

Technical Validation

Predicting transition temperature using Monte Carlo

The quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) method is among the most accurate approaches for determining the transition temperatures of magnetic materials. However, its applicability is often limited by the fermion sign problem, especially in frustrated systems27. Additionally, accounting for finite-size effects in QMC simulations is highly computationally demanding.

Other methods, such as mean field theory (MFT)28 and the random phase approximation (RPA)29,30,31, are also used. MFT tends to overestimate the transition temperature compared to experimental results, while RPA improves upon MFT and yields more accurate predictions30,31,32,33. However, applying RPA requires specific techniques and details, such as the magnetic ordering vector, which limits its use to researchers with sufficient theoretical knowledge32.

Classical MC can be a useful tool for providing a rough estimate of the transition temperature in magnetic materials. However, when using INS data fitted with spin-wave theory, classical MC simulations tend to underestimate the transition temperature11. This discrepancy casts doubt on the reliability of the INS data34. Since spin-wave theory incorporates quantum mechanical effects in fitting inelastic neutron scattering (INS) data, including the factor (S + 1)/S is essential for obtaining accurate results from classical Monte Carlo (MC) simulations. This factor arises from comparing the quantum and classical expressions for the expectation value of the squared spin operator. In the quantum case, ⟨S2⟩ is proportional to S(S + 1), whereas in the classical limit it scales as S2. To reconcile these two approaches, either the exchange parameters used in classical MC simulations or the transition temperatures obtained from classical MC must be rescaled by the factor (S + 1)/S11.

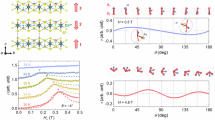

Figure 2 shows the transition temperatures obtained from MC simulations (TMC) for all 72 compounds, revealing a significant deviation from the experimental transition temperatures. However, applying the (S + 1)/S correction:

significantly improves the accuracy of transition temperature predictions.

Results from MC simulations for 72 compounds. TMC represents the transition temperature obtained from MC simulations using exchange parameters derived from INS data fitted with spin-wave theory. \({T}_{{\rm{MC}}}^{\ast }\) denotes the quantum-corrected transition temperature, obtained by applying the correction factor (S + 1)/S to TMC. All data points shown in this diagram are provided in Supplementary information.

The MAPE for \({T}_{{\rm{MC}}}^{* }\) is 9.6%, whereas for TMC, the error is much greater, equal to 35.1%. For 36% of the compounds, the absolute percentage error (APE) is less than 5%. In 32% of the cases, APE falls between 5% and 10%, while for 11% of the compounds, it ranges from 10% to 15%. Only 21% of the compounds exhibit an APE greater than 15%. The detailed data from the MC simulations shown in Fig. 2 are provided in Supplementary information.

It is important to note that exchange interactions derived from INS data are subject to several approximations. First, LSWT itself is an approximation to spin-wave theory when fitting INS data to a spin Hamiltonian. Second, in practice, only the dominant exchange terms are typically included in the spin Hamiltonian, while weaker interactions (such as single-ion anisotropy or longer-range couplings) are often neglected. Finally, exchange parameters are not strictly constant but may vary with temperature in practice35,36,37. Another source of error arises from the classical nature of Monte Carlo simulations: while classical spin models become exact in the large-S limit, quantum effects can play a role for small spin values. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that for S ≥ 1 the difference between quantum and classical Monte Carlo results is usually minor, and even for \(S=\frac{1}{2}\) the deviations remain small12,13. Finite-size effects in the simulations can also lead to systematic shifts in the transition temperature. Taken together, these experimental and theoretical limitations account for the observed deviations between our predicted and experimental transition temperatures.

As a result, calculating an exact transition temperature is not solely dependent on theoretical methods; it also relies on the accuracy of experimentally derived exchange interactions. This means that even with a perfect theoretical approach, expecting a transition temperature that exactly matches experimental results is unrealistic.

Refining Spin Hamiltonians Using Monte Carlo Results

From the plot (Fig. 2), we can establish two key observations:

-

The transition temperature obtained from classical MC simulations (TMC) is always lower than the experimental transition temperature (TExp.), i.e., TMC < TExp..

-

The quantum correction factor (S + 1)/S accurately accounts for this discrepancy in most cases.

These observations provide useful criteria for assessing the accuracy of exchange parameters derived from INS data using spin-wave theory. In the following, we discuss several cases to illustrate how these criteria can be used to identify better models and filter out unreliable data.

NiO is one of the most extensively studied antiferromagnetic compounds, with a transition temperature of 523 K and a quantum spin number S = 1. However, only a single INS dataset exists for it38. In the INS study, two different Heisenberg models were used to fit the data: a J1 − J2 model (including only first- and second-nearest-neighbor exchange interactions) and a J1 − J4 model (including interactions up to the fourth nearest neighbor).

Using the J1 − J2 model, the MC simulation yields TMC = 310 K and \({T}_{{\rm{MC}}}^{* }=620\) K. In contrast, the J1-J4 model produces TMC = 304 K and \({T}_{{\rm{MC}}}^{* }=608\) K, suggesting that the J1 − J4 model provides a more accurate estimate of the transition temperature.

Another example is MnBi2Te4, for which two successive research papers were published by overlapping groups of authors18,39. This compound has an experimental magnetic transition temperature of 24 K and a spin quantum number of S = 5/2. All spin models considered in these studies include intra-layer exchange interactions (J1, J2, … ) and an inter-layer exchange interaction (Jc).

In the first study18, the authors introduced the J1–J2–J4 model, which resulted in a MC transition temperature TMC = 14.7 K and a corrected transition temperature \({T}_{{\rm{MC}}}^{* }=20.58\) K (See Fig. 3). In the more recent work39, the model was extended to include exchange interactions up to the 7th nearest neighbor (J1–J7), and an alternative model incorporating anisotropic inter-layer exchange (\({J}_{c}^{{\rm{aniso}}}\)) was also proposed.

Magnetic specific heat calculated from MC simulations for three different spin models of MnBi2Te4, based on parameters obtained from INS data. The J1-J2-J4 model was introduced in Ref. 18, while the J1-J7 and \({J}_{c}^{{\rm{aniso}}}\) models were proposed in Ref. 39. The peak of the specific heat defines the MC transition temperature, TMC. The values of TMC for the J1-J2-J4, J1-J7, and \({J}_{c}^{{\rm{aniso}}}\) models are 14.7 K, 15.3 K, and 16.7 K, respectively.

MC simulations using the J1–J7 model yield TMC = 15.3 K and \({T}_{{\rm{MC}}}^{* }=21.42\) K (See Fig. 3). For the \({J}_{c}^{{\rm{aniso}}}\) model, the results improve further to TMC = 16.7 K and \({T}_{{\rm{MC}}}^{* }=23.38\) K, suggesting that the \({J}_{c}^{{\rm{aniso}}}\) model provides the best agreement with the experimental data.

During our investigation, we found instances where the transition temperature obtained from Monte Carlo simulations (TMC) exceeded the experimental value, and other cases where the quantum-corrected temperature (\({T}_{{\rm{MC}}}^{* }\)) was significantly lower. Such discrepancies often indicate problems with the INS data or the fitting procedure. These issues may stem from an incorrectly defined Hamiltonian-such as a missing factor of 1/2-poor data fitting, or an inaccurate estimate of the spin quantum number S. For example, using the INS-derived exchange interactions for LiNiPO440, LiCoPO441, and LiMnPO442, the MC-calculated transition temperatures (TMC) are overestimated. This points to a mismatch between the spin Hamiltonian and the spin-wave formalism, likely caused by an omitted factor of 1/2 in the Hamiltonian. A closer examination of the spin-wave equations used in these studies supports this conclusion.

Through analysis of more than 100 INS studies that derived exchange interactions from spin-wave theory, we identified 72 compounds with reliable data and compiled them into a standardized database. This database includes exchange interaction parameters, spin quantum numbers, reference sources, MC simulation results, structure files, and visualized structures. Using this dataset, we investigated the accuracy of transition temperature predictions by applying the (S + 1)/S correction to classical MC results. Our findings show that, in most cases, the corrected results align more closely with experimental values, achieving a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 9%. We propose classical MC simulations and the (S + 1)/S correction as useful tools for refining INS data and identifying potential inconsistencies.

Comparison with theories

To provide further insight into the data, we analyze the role of the local atomic environment in determining the exchange interactions. For this purpose, we focus on the bond angle (M1-L-M2) between two magnetic atoms (M1, M2) bridged by a ligand (L), together with the distance between the magnetic atoms (M1-M2). To ensure that the bond angle is well defined, we restrict the analysis to cases where the two magnetic atoms are symmetrically coordinated by the ligand (M1-L = M2-L). Exchange pathways involving more than one intermediate atom (e.g., M1-L-M2-L-M3 or M1-L1-L2-M2) are excluded from the analysis, since the bond angle cannot be uniquely defined in such cases. Figure 4 presents the resulting diagram of exchange interactions as a function of bond angle and interatomic distance. The overall trend is broadly consistent with one of the Goodenough-Kanamori-Anderson (GKA) rules43,44,45: bond angles close to 180° generally favor antiferromagnetic interactions (J < 0), while bond angles near 90° more often lead to ferromagnetic interactions (J > 0). It is also important to note that the GKA rules further emphasize the dependence of exchange on the d-orbital filling of the magnetic ions. However, INS data, together with theoretical calculations, clearly demonstrate that the GKA rules are not universally valid. A representative example is KCuF3, where two Cu-F-Cu pathways both have bond angles of ~180° (corresponding to Cu-Cu distances of 3.92 Å and 4.14 Å), yet one interaction is antiferromagnetic while the other is ferromagnetic. This shows that while the GKA rules provide valuable qualitative guidance, the actual exchange interactions also depend sensitively on factors such as orbital hybridization, covalency, and details of the crystal structure.

The diagram illustrates the exchange interaction as a function of the bond angle (M1-L-M2) between magnetic atoms (M1, M2) and the ligand (L), and the interatomic distance (M1-M2). Red and blue circles represent ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic interactions, respectively. The circle radius is proportional to the square root of the interaction strength, i.e., \(\sqrt{| J| }\).

Comparisons between INS-derived exchange parameters and those obtained from density functional theory (DFT) are highly valuable, but they must be treated with care, as DFT results can vary significantly depending on the choice of basis set, exchange-correlation functional, and other methodological details. To ensure consistency and avoid ambiguities that might arise from mixing results obtained with different approaches (e.g., those available in public databases), we restrict our comparison to two of our previous systematic studies, in which a uniform computational strategy was applied across all compounds. In the first study46, we employed DFT+U47 with the Hubbard parameter determined self-consistently using linear response theory, while in the second study48 we used the meta-GGA r2SCAN49 functional to calculate exchange interactions. Thirteen compounds are common to both of these earlier works and the present INS dataset. For these systems, we compare the maximum exchange interaction obtained from INS, DFT+U, and meta-GGA r2SCAN (Fig. 5). The results reveal a clear trend: DFT+U tends to underestimate the exchange interaction strength relative to INS, whereas meta-GGA r2SCAN generally overestimates it. These comparisons, however, should be interpreted with caution. In our earlier DFT studies, the mapping was carried out onto a classical Heisenberg Hamiltonian, while in the present INS analysis the mapping is performed within LSWT, which explicitly incorporates quantum effects. This methodological distinction likely contributes to the observed discrepancies between theory and experiment.

Code availability

This study did not involve the development of new code.

References

Boothroyd, A. T. Principles of neutron scattering from condensed matter (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Fishman, R. S., Fernandez-Baca, J. A., and Rõõm, T. Spin-Wave Theory and its Applications to Neutron Scattering and THz Spectroscopy, 2053-2571 (Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2018).

Shirane, G., Shapiro, S. M., and Tranquada, J. M. Neutron Scattering with a Triple-Axis Spectrometer: Basic Techniques (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Toth, S. & Lake, B. Linear spin wave theory for single-Q incommensurate magnetic structures. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 27, 166002 (2015).

Auerbach, A., Interacting electrons and quantum magnetism (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Heisenberg Magnets, in Lecture Notes on Electron Correlation and Magnetism (WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 1999) pp. 263–340.

Gallego, S. V. et al. MAGNDATA: towards a database of magnetic structures. I.The commensurate case. Journal of Applied Crystallography 49, 1750 (2016).

Cox, D. Neutron-diffraction determination of magnetic structures. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 8, 161 (1972).

Izyumov, R. P. O. Y. A., Naish, V. E., Neutron diffraction of magnetic materials (Springer New York, NY, 2012).

Newman, M. and Barkema, G. Monte Carlo Methods in Statistical Physics (Clarendon Press, 1999).

Alaei, M. & Karimi, H. A deep investigation of NiO and MnO through the first principle calculations and Monte Carlo simulations. Electronic Structure 5, 025001 (2023).

Körmann, F., Dick, A., Hickel, T. & Neugebauer, J. Rescaled Monte Carlo approach for magnetic systems: Ab initio thermodynamics of bcc iron. Phys. Rev. B 81, 134425 (2010).

Walsh, F., Asta, M. & Wang, L.-W. Realistic magnetic thermodynamics by local quantization of a semiclassical Heisenberg model. npj Computational Materials 8, 186 (2022).

Magnetic Data Repository - INS_SW_MC, https://github.com/malaei/Magnetic_data/tree/main/INS_SW_MC (2025).

Alaei, M., Rezaei, N., and Mosleh, Z., exchange interactions derived from fitting inelastic neutron scattering. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17160565 (2025).

Tobin, S. M. et al. Magnetic excitations in the topological semimetal YbMnSb2. Phys. Rev. B 107, 195146 (2023).

Soh, J.-R. et al. Magnetic structure and excitations of the topological semimetal YbMnBi2. Phys. Rev. B 100, 144431 (2019).

Li, B. et al. Competing magnetic interactions in the antiferromagnetic topological insulator mnbi2te4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 167204 (2020).

Yamani, Z., Tun, Z. & Ryan, D. H. Neutron scattering study of the classical antiferromagnet mnf2: a perfect hands-on neutron scattering teaching coursespecial issue on neutron scattering in canada. Canadian Journal of Physics 88, 771 (2010).

Morano, V. C. et al. Absence of altermagnetic magnon band splitting in MnF2 arXiv:2412.03545 [cond-mat.str-el] (2024).

Okazaki, A., Turberfield, K. & Stevenson, R. Neutron inelastic scattering measurements of antiferromagnetic excitations in MnF2 at 4.2°K and at temperatures up to the neel point. Physics Letters 8, 9 (1964).

Tonegawa, T. Theory of Magnon Sidebands in MnF2. Progress of Theoretical Physics 41, 1 (1969).

Rössler, U. Solid state theory: an introduction (Springer Science & Business Media, 2009).

Rezende, S. M. Fundamentals of magnonics, Vol. 969 (Springer, 2020).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. Journal of Applied Crystallography 44, 1272 (2011).

Rezaei, N., Alaei, M. & Akbarzadeh, H. ESpinS: A program for classical Monte-Carlo simulations of spin systems. Computational Materials Science 202, 110947 (2022).

Troyer, M. & Wiese, U.-J. Computational Complexity and Fundamental Limitations to Fermionic Quantum Monte Carlo Simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 170201 (2005).

Johnston, D. C. Unified molecular field theory for collinear and noncollinear Heisenberg antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 91, 064427 (2015).

Pajda, M., Kudrnovský, J., Turek, I., Drchal, V. & Bruno, P. Ab initio calculations of exchange interactions, spin-wave stiffness constants, and Curie temperatures of Fe, Co, and Ni. Phys. Rev. B 64, 174402 (2001).

Sato, K. et al. First-principles theory of dilute magnetic semiconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1633 (2010).

Rajeev Pavizhakumari, V., Skovhus, T. & Olsen, T. Beyond the random phase approximation for calculating Curie temperatures in ferromagnets: application to Fe, Ni, Co and monolayer CrI3. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 37, 115806 (2025).

Pavizhakumari, V. R. and Olsen, T. Predicting the Néel temperatures in general helimagnetic materials: a comparison between mean field theory, random phase approximation, renormalized spin wave theory and classical Monte Carlo simulations (2025), arXiv:2503.01283 [cond-mat.mtrl-sci].

Fischer, G. et al. Exchange coupling in transition metal monoxides: Electronic structure calculations. Phys. Rev. B 80, 014408 (2009).

Archer, T. et al. Exchange interactions and magnetic phases of transition metal oxides: Benchmarking advanced ab initio methods. Phys. Rev. B 84, 115114 (2011).

Güdel, H. U., Furrer, A., Bührer, W. & Hälg, B. Exchange interactions in clusters of paramagnetic transition metal ions; inelastic neutron scattering studies. Surface Science 106, 432 (1981).

Naser, H., Rado, C., Lapertot, G. & Raymond, S. Anisotropy and temperature dependence of the spin-wave stiffness in nd2fe14B: An inelastic neutron scattering investigation. Phys. Rev. B 102, 014443 (2020).

Rózsa, L., Atxitia, U. & Nowak, U. Temperature scaling of the dzyaloshinsky-moriya interaction in the spin wave spectrum. Phys. Rev. B 96, 094436 (2017).

Hutchings, M. T. & Samuelsen, E. J. Measurement of Spin-Wave Dispersion in NiO by Inelastic Neutron Scattering and Its Relation to Magnetic Properties. Phys. Rev. B 6, 3447 (1972).

Li, B. et al. Quasi-two-dimensional ferromagnetism and anisotropic interlayer couplings in the magnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te4. Phys. Rev. B 104, L220402 (2021).

Jensen, T. B. S. et al. Anomalous spin waves and the commensurate-incommensurate magnetic phase transition in LiNiPO4. Phys. Rev. B 79, 092413 (2009).

Tian, W., Li, J., Lynn, J. W., Zarestky, J. L. & Vaknin, D. Spin dynamics in the magnetoelectric effect compound LiCoPO4. Phys. Rev. B 78, 184429 (2008).

Li, J. et al. Antiferromagnetism in the magnetoelectric effect single crystal limnpo4. Phys. Rev. B 79, 144410 (2009).

Goodenough, J. B. An interpretation of the magnetic properties of the perovskite-type mixed crystals la1−xsrxcoo3−λ. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 6, 287 (1958).

Goodenough, J. B. Theory of the role of covalence in the perovskite-type manganites [La, m(II)]Mno3. Phys. Rev. 100, 564 (1955).

Kanamori, J. Superexchange interaction and symmetry properties of electron orbitals. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 10, 87 (1959).

Mosleh, Z. & Alaei, M. Benchmarking density functional theory on the prediction of antiferromagnetic transition temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 108, 144413 (2023).

Liechtenstein, A. I., Anisimov, V. I. & Zaanen, J. Density-functional theory and strong interactions: Orbital ordering in mott-hubbard insulators. Phys. Rev. B 52, R5467 (1995).

Rezaei, N., Alaei, M. & Oganov, A. R. Evaluating scan and r2SCAN meta-gga functionals for predicting transition temperatures in antiferromagnetic materials. Phys. Rev. B 111, 144406 (2025).

Furness, J. W., Kaplan, A. D., Ning, J., Perdew, J. P. & Sun, J. Accurate and Numerically Efficient r2SCAN Meta-Generalized Gradient Approximation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 11, 8208 (2020).

Acknowledgements

M. A. acknowledges financial support from the Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) under Project No. 4002648. N. R. and A. R. O. acknowledge support from the Russian Science Foundation under Grant No. 19-72-30043.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mojtaba Alaei conducted and supervised the project, performed part of the Monte Carlo (MC) simulations, prepared data for the GitHub repository, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. Zahra Mosleh gathered data, prepared inputs for the MC simulations, and contributed to structural visualization. Nafise Rezaei carried out MC simulations, contributed to structural visualization, and participated in manuscript writing. Artem R. Oganov provided intellectual input and financial support. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alaei, M., Mosleh, Z., Rezaei, N. et al. Experimental Exchange Interaction Dataset for Magnetic Materials: Spin Waves to MC Simulations. Sci Data 12, 1832 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06099-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06099-x