Abstract

Qilian Mountains National Park in northwestern China encompasses ecologically sensitive desert steppe ecosystems increasingly affected by rodent population outbreaks—particularly of Rhombomys opimus and Meriones meridianus. In response, large-scale chemical rodent control campaigns have been implemented, raising concerns about unintended effects on non-target predators and overall biodiversity. To inform ecologically sound pest management and support long-term biodiversity monitoring, we deployed 22 infrared-triggered camera traps representative desert steppe habitats within the park from December 2020 to January 2022, accumulating 553,814 images over 8,052 trap-days. After two rounds of expert validation, 28,881 images containing clearly identifiable wildlife were retained, documenting 26 vertebrate species across Mammalia, Aves, and Reptilia. The dataset includes comprehensive metadata and 3,828 temporally independent detection events, enabling analyses of species distributions, predator–prey interactions, diel activity rhythms, and automated wildlife recognition. This openly accessible resource fills a critical data gap for biodiversity assessment in chemically managed drylands and provides a valuable foundation for conservation planning in Qilian Mountains National Park.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The Qilian Mountains National Park(QMNP), located at the convergence of the Qinghai–Tibet and Inner Mongolia Plateaus, functions as a critical ecological barrier and a nationally designated biodiversity conservation area in northwestern China1,2. Within this landscape, the desert steppe emerges as an ecologically sensitive and biodiverse system that remains highly susceptible to environmental perturbation3. In recent years, population outbreaks of small rodents—most notably the great gerbil (Rhombomys opimus) and the midday gerbil (Meriones meridianus)—have exacerbated vegetation degradation, diminished rangeland productivity, and disrupted ecosystem stability4,5,6.

In response, large-scale chemical control campaigns have been implemented to suppress rodent populations and restore vegetation7,8,9. While effective in the short term, these interventions carry substantial risks for non-target species, particularly native predators, and may trigger cascading ecological effects such as trophic imbalances and biodiversity loss8,10,11,12. Despite these concerns, there remains a paucity of empirical data documenting the spatiotemporal dynamics of rodents, their predators, and other sympatric fauna in arid grassland ecosystems.

To help fill this gap, we employed infrared-triggered camera traps—now widely recognized as indispensable tools for non-invasive wildlife monitoring across extensive spatial and temporal scales13,14,15. These systems are particularly effective for detecting cryptic, nocturnal, and fossorial species, making them ideal for monitoring small mammals and their ecological interactions in desert landscapes. Nonetheless, camera-trap datasets from the desert steppe in QMNP remain scarce.

Here, we present a high-frequency, expert-curated camera-trap dataset from representative desert steppe habitats, situated within a core ecological region of the northern Qilian Mountains in the park. This dataset encompasses vertebrate detections across multiple taxonomic groups and is enriched with detailed metadata, including timestamps, georeferenced camera coordinates, and species-level annotations—together providing a robust platform for ecological analysis and computational research.

By making this dataset publicly accessible, we aim to advance research in community ecology, species distribution modeling, conservation planning, and machine learning-based wildlife identification16,17. The dataset offers crucial insights to inform biodiversity-conscious rodent management and supports evidence-based conservation strategies in fragile dryland ecosystems.

Methods

Study area

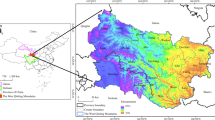

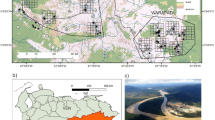

This study was conducted in the desert steppe ecosystem of Sunan Yugur Autonomous County, located in the northern Qilian Mountains of Gansu Province, China (38°30′–39°15′N, 99°00′–100°02′E) (Fig. 1). The region experiences an arid continental climate, with a mean annual temperature of approximately 4 ± 0.5 °C and annual precipitation averaging 260 ± 10 mm, most of which occurs between May and August. Vegetation is characterized by drought-tolerant shrub–grassland mosaics dominated by Sympegma regelii, Salsola passerina, Allium polyrhizum, and Reaumuria soongorica.

This ecosystem supports a characteristic assemblage of desert-steppe vertebrates, including small mammals such as the midday gerbil and great gerbil, as well as their predators such as the Pallas’s cat (Otocolobus manul) and red fox (Vulpes vulpes). Arid-adapted birds like the isabelline wheatear (Oenanthe isabellina) and ground tit (Pseudopodoces humilis) are also commonly observed. This community exemplifies the biodiversity and trophic interactions typical of Central Asian desert ecosystems18.

Camera trap deployment

From December 2020 to January 2022, 22 infrared-triggered camera traps (model: Ltl-6210PLUS, Shenzhen Ltl Acorn Electronics Co., Ltd.) were systematically deployed across representative shrub–grassland habitats in Sunan Yugur Autonomous County. Site selection was stratified according to rodent population density, which was directly assessed through field surveys prior to camera deployment. To maximize detection efficiency, cameras were preferentially placed in areas with relatively high rodent density. Each camera was mounted 0.5–1.0 m above ground level and positioned to face active rodent burrows or foraging trails, maximizing the probability of wildlife detection19. No baits, including acoustic, olfactory, or food attractants, were used during deployment.

Cameras were equipped with passive infrared (PIR) sensors with a detection range of 18 m and infrared flash illumination effective up to 35 m (850 nm standard lens version). Lenses included either a standard 55° field of view or a 100° wide-angle option. Each trigger event captured three consecutive images with a trigger speed of 0.8 s and no delay between successive triggers (0 s interval), allowing for continuous 24-hour monitoring. Maintenance visits were conducted approximately every two months to ensure operational consistency, including battery replacement and image retrieval.

Image processing and filtering

Captured images were reviewed by trained personnel to exclude empty frames, environmental false triggers (e.g., vegetation movement, precipitation), and unidentifiable animals. A total of 28,881 images were retained as valid wildlife detections.

Each valid image was annotated with standardized metadata, including camera ID, timestamp, and species identification. To reduce temporal autocorrelation and ensure event independence, detections of the same species at the same location were defined as separate events only if they were at least 30 minutes apart—a widely accepted threshold in camera trap studies20,21,22.

Species identification and quality control

Species identification was conducted to the finest taxonomic resolution possible by expert annotators, guided by A Field Guide to the Mammals of China and A Field Guide to the Birds of China. Taxonomy followed the latest frameworks from the Checklist of Mammals in China (2021 edition) and the Classification and Distribution Checklist of Birds of China (3rd edition)23,24,25,26.

Because many small mammal species exhibit cryptic morphology that challenges visual identification in infrared images, supplementary live trapping was conducted both prior to and following camera deployment27. Captured specimens were identified using external features and cranial morphology, serving as physical references for image-based classification.

To ensure annotation consistency and minimize observer bias, all images underwent two rounds of independent screening by separate teams. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions. This dual-stage validation protocol achieved high inter-observer agreement and ensured reliable species-level classification, enhancing the overall integrity of the dataset28.

Data Records

The dataset is publicly available on Zenodo29,30, under the following DOIs: Valid species images and documentation (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15730802) and independent detection events and documentation (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15733158). To support data exploration and reuse, we provide two summary tables: Table 1 describes camera-level sampling effort and output, and Table 3 summarizes species-level detection frequencies.

The dataset comprises three integrated components: a validated image set (valid_species_images.zip) containing 28,881 infrared images of wildlife together with a metadata file (metadata.csv); an independent detection event table (independent_events.zip) summarizing 3,828 temporally independent wildlife detections; and a documentation bundle (documentation_and_summaries.csv) providing detailed site coordinates, species detection summaries, and camera operation statistics.

Comprehensive documentation is included to support effective use of the dataset. This includes a README file offering an overview of the dataset and usage instructions, a detailed data dictionary defining metadata fields and file structures, summaries of camera operation effort and species detections to aid analytical planning, and precise camera coordinates in WGS84 georeferenced format to enable spatial analyses.

It comprises a manually validated dataset of infrared camera-trap images and associated metadata collected in the desert steppe of Sunan Yugur Autonomous County, Gansu Province, China. The data reflect spatiotemporal occurrences of vertebrate species captured during a high-frequency monitoring effort. All records underwent dual independent expert reviews to ensure annotation accuracy and consistency. A subset of the dataset represents independent detection events based on standardized temporal thresholds, following common practices in camera-trap research.

All validated entries share a unified metadata schema (Table 2), provided as UTF-8 encoded CSV files to ensure cross-platform compatibility and ease of integration into ecological and computational workflows.

These records are intended to support a wide range of applications, including species distribution modeling, diel and seasonal activity analysis, biodiversity monitoring, and the development of machine learning models for automated wildlife classification Fig. 2.

Technical Validation

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the dataset, a series of validation procedures was implemented throughout all stages of data collection and processing, including camera functionality, image annotation, species identification, and metadata verification.

Camera operation and data consistency

All 22 infrared-triggered camera traps remained continuously operational from December 2020 to January 2022. Field teams conducted routine maintenance at two-month intervals, including battery replacement and data retrieval, to minimize equipment failure and ensure stable image acquisition throughout the monitoring period.

Image screening and annotation reliability

Image review and annotation were independently conducted by two expert teams from the Engineering Technology Research Center for Rodent Pest Control on Alpine Grasslands, under the National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Annotators systematically removed empty frames, false triggers (e.g., caused by vegetation movement or lighting artifacts), and images containing unidentifiable subjects. Discrepancies between the two teams were resolved through consensus discussions, resulting in a high inter-observer agreement rate of 96%. This dual-review workflow ensured consistency, reduced observer bias, and enhanced annotation reliability.

Species identification accuracy

All species annotations followed authoritative field guides and national taxonomic standards. To support the accurate classification of morphologically similar rodents, live trapping was conducted both prior to and following camera deployment. Captured specimens provided reliable reference material, particularly for distinguishing nocturnal or cryptic species with subtle morphological features. This approach substantially improved the taxonomic resolution and accuracy of rodent identification within the image dataset.

Metadata integrity and file structure

Metadata quality was verified through internal cross-checks to ensure completeness, accuracy, and traceability. Each image file was systematically named to reflect its source camera station, and all metadata were stored in UTF-8 encoded CSV format for compatibility across platforms. Standardized metadata fields—including species name, timestamp, and camera ID—enabled seamless integration into ecological models, activity pattern analyses, and machine learning pipelines.

Data availability

The datasets generated and described in this Data Descriptor are publicly available on Zenodo under the following DOIs: validated species images and documentation https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15730802 and independent detection events and documentation https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15733158.

Code availability

The scripts used for image timestamp extraction and independent event filtering are openly available on GitHub at https://github.com/Yangyang875/Yangyang875-CameraTrapTools. The repository contains two Python scripts: extract_timestamps.py, which extracts capture timestamps from image EXIF metadata, and filter_independent_events.py, which identifies independent events from camera trap datasets and copies the corresponding images. The code requires Python 3.8 or higher, with dependencies listed in the README file.

References

Pu, L., Lu, C., Yang, X. & Chen, X. Spatio-Temporal Variation of the Ecosystem Service Value in Qilian Mountain National Park (Gansu Area) Based on Land Use. Land 12, 201, https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010201 (2023).

Li, J., Huang, Y., Guo, L., Sun, Z. & Jin, Y. Operationalizing the social-ecological systems framework in a protected area: a case study of Qilian Mountain National Park, northwestern China. Ecol. Soc. 29, https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-15466-290330 (2024).

Du, Q., Sun, Y., Guan, Q., Pan, N. & Wang, Q. Vulnerability of grassland ecosystems to climate change in the Qilian Mountains, northwest China. J. Hydrol. 612, 128305, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128305 (2022).

Brown, J. H. & Heske, E. J. Control of a Desert-Grassland Transition by a Keystone Rodent Guild. Science 250, 1705–1707, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.250.4988.1705 (1990).

Kelt, D. A. Comparative ecology of desert small mammals: a selective review of the past 30 years. J. Mammal. 92, 1158–1178, https://doi.org/10.1644/10-MAMM-S-238.1 (2011).

Hope, A. G., Gragg, S. F., Nippert, J. B. & Combe, F. J. Consumer roles of small mammals within fragmented native tallgrass prairie. Ecosphere 12, e03441, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3441 (2021).

Dickman, C. R. Rodent–ecosystem relationships: a review. In: Singleton, G. R., Hinds, L. A., Leirs, H. & Zhang, Z. (eds.) Ecologically-Based Management of Rodent Pests, vol. 59, 113–133 (ACIAR, 1999).

Augustine, D. J., Smith, J. E., Davidson, A. D. & Stapp, P. Burrowing rodents. in Rangeland Wildlife Ecology and Conservation (eds. Krausman, P. R. & Cain, J. W.) 505–548 (Springer, Cham, 2023).

Longland, W. S. & Dimitri, L. A. Kangaroo rats: ecosystem engineers on western rangelands. Rangelands 43, 72–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rala.2020.10.004 (2021).

Wan, X., Yan, C., Wang, Z. & Zhang, Z. Sustained population decline of rodents is linked to accelerated climate warming and human disturbance. BMC Ecol. Evol. 22, 102, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-022-02056-z (2022).

Liu, X., Xu, L., Zheng, J., Lin, J. & Li, X. Great Gerbils (Rhombomys opimus) in Central Asia Are Spreading to Higher Latitudes and Altitudes. Ecol. Evol. 14, e70517, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.70517 (2024).

Delibes-Mateos, M., Smith, A. T., Slobodchikoff, C. N. & Swenson, J. E. The paradox of keystone species persecuted as pests: a call for the conservation of abundant small mammals in their native range. Biol. Conserv. 144, 1335–1346, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.02.012 (2011).

Boitani, L. Camera Trapping for Wildlife Research (Pelagic Publishing Ltd, Exeter, 2016).

Caravaggi, A. et al. A review of camera trapping for conservation behaviour research. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 3, 109–122, https://doi.org/10.1002/rse2.48 (2017).

Steenweg, R. et al. Scaling-up camera traps: monitoring the planet’s biodiversity with networks of remote sensors. Front. Ecol. Environ. 15, 26–34, https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1448 (2017).

Norouzzadeh, M. S. et al. Automatically identifying, counting, and describing wild animals in camera-trap images with deep learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E5716–E5725, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1719367115 (2018).

Reyserhove, L., Norton, B. & Desmet, P. Best practices for managing and publishing camera trap data. GBIF Secretariat: Copenhagen. https://doi.org/10.35035/doc-0qzp-2x37 (2023).

Zeng, Z.-G. et al. Effects of habitat alteration on lizard community and food web structure in a desert steppe ecosystem. Biol. Conserv. 179, 86–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.011 (2014).

Hopkins, J., Santos-Elizondo, G. M. & Villablanca, F. Detecting and monitoring rodents using camera traps and machine learning versus live trapping for occupancy modeling. Front. Ecol. Evol. 12, 1359201, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2024.1359201 (2024).

Iannarilli, F., Erb, J., Arnold, T. W. & Fieberg, J. R. Evaluating species-specific responses to camera-trap survey designs. Wildl. Biol. 2021, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.2981/wlb.00726 (2021).

Peral, C., Landman, M. & Kerley, G. The inappropriate use of time-to-independence biases estimates of activity patterns of free-ranging mammals derived from camera traps. Ecol. Evol. 12, 9408, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9408 (2022).

Smith, K. An empirical assessment of the role of independence filters in temporal activity analyses using camera trapping data. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 79, 2, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-024-03544-6 (2025).

Smith, A. T. & Yan, X. Mammals of China (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2013).

MacKinnon, J. R. & Phillipps, K. A Field Guide to the Birds of China (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000).

Zheng, G. A Checklist on the Classification and Distribution of the Birds of China. (Geological Publishing House, Beijing, 2005).

Zhang, Y. et al. Assessment of Red List of birds in China. Biodivers. Sci. 24, 568–577, https://doi.org/10.17520/biods.2015294 (2016).

Burns, P. A., Parrott, M. L., Rowe, K. C. & Phillips, B. L. Identification of threatened rodent species using infrared and white-flash camera traps. Aust. Mammal. 40, 188–197, https://doi.org/10.1071/AM17016 (2017).

Zett, T., Stratford, K. J. & Weise, F. J. Inter-observer variance and agreement of wildlife information extracted from camera trap images. Biodivers. Conserv. 31, 3019–3037, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-022-02472-z (2022).

Wei, C., Ma, Y., Fan, Y., Zhi, X. & Hua, L. Annotated Infrared Camera Trap Images from the Desert-Steppe of Northern Qilian Mountains (2020–2022) (v1.0) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15730802 (2025).

Wei, C., Ma, Y., Fan, Y., Zhi, X. & Hua, L. Annotated Infrared Camera Trap Images from the Desert-Steppe of Northern Qilian Mountains (2020–2022) (v1.0) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15733158 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Open Competition Project of the Key Laboratory of Grassland Ecosystem, Ministry of Education (Grant No.KLGE202406; KLGE202206), and the “Innovation Star” Outstanding Graduate Projects of the Gansu Provincial Department of Education (Grant Nos. 2025CXZX-848 and 2025CXZX-846). We thank Mr. Jun Wang of Grassland WorkStation in Sunan Yugur Autonomous County and laboratory team members for their contributions to camera deployment, image screening, and data validation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Caibo Wei led the preparation of the manuscript, including dataset structuring, data analysis, and writing. Yijie Ma was responsible for infrared camera deployment, maintenance, and data collection in the field. Yijie Ma and Yuquan Fan performed the first round of image screening and filtering. Xiaoliang Zhi and Caibo Wei conducted the second round of image validation to ensure data quality. Limin Hua provided supervision, contributed to manuscript revision, and served as the corresponding author. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, C., Ma, Y., Fan, Y. et al. Camera Trap Dataset of Rodents and Sympatric Vertebrates in the Desert Steppe of Qilian Mountains China. Sci Data 12, 1831 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06105-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06105-2