Abstract

Scurrula parasitica (Loranthaceae) is a widespread aerial hemiparasitic plant in southwest China, recognized for its ecological roles and broad host range. As a representative of mistletoes in Santalales, it serves as a model for studying the genomic basis of aerial hemiparasitism. Here, we present a high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly of S. parasitica using PacBio high-fidelity and Hi-C sequencing. The assembled genome spans 547.41 Mb with a contig N50 of 8.32 Mb, and 97.54% of the sequence is anchored to nine pseudochromosomes. Repetitive sequences account for 64.53% of the genome. We predicted 21,837 protein-coding genes, of which 20,974 (96.05%) received functional annotations.Additionally, we identified 1,271 transcription factor genes and 8,407 non-coding RNAs. This chromosome-level assembly provides a foundational resource for investigating gene family evolution, parasitic adaptation, and genome architecture in S. parasitica. The genome assembly and associated datasets have been deposited in public repositories, enabling future comparative and functional genomic studies in parasitic angiosperms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Approximately 1% of angiosperms are parasitic plants, either fully or partially dependent on their host plants for carbon, nutrients, and water through specialized structures known as haustoria1. These plants exhibit diverse morphological and physiological adaptations and have evolved multiple times independently in at least 16 angiosperm families1,2. Parasitic strategies range from hemiparasitism, in which plants retain photosynthetic ability, to holoparasitism, in which they rely entirely on their hosts2. This diversity suggests complex and lineage-specific genomic adaptations3,4.

Recent advances in genome sequencing have enabled studies on several parasitic plant species. Published genomes include hemiparasites such as Santalum album5, Malania oleifera6, Striga asiatica7, Phtheirospermum japonicum8, and Pedicularis cranolopha9, as well as holoparasites like Cuscuta campestris10, C. australis11, Orobanche cumana, Phelipanche aegyptiaca12, and Sapria himalayana13,14. Comparative genomic analyses have revealed shared features such as extensive gene loss, plastome and mitogenome reduction, and horizontal gene transfer from host plants10,11,13. However, due to the limited number of high-quality genomes, broader evolutionary patterns across parasitic lineages remain poorly understood.

Mistletoes represent a major clade of hemiparasitic plants in Santalales, where aerial parasitism evolved independently multiple times from root-parasitic ancestors15,16. Scurrula parasitica (Loranthaceae) is a widespread mistletoe species in southwest China. Seeds dispersed by birds and mammals germinate on host branches and form haustoria to establish parasitic relationships17. In contrast to root-parasitic Santalales such as Santalum album and Malania oleifera, S. parasitica parasitizes woody branches and has a broad host range, including Osmanthus, Citrus, and Camellia, making it a valuable model for investigating the genomic basis of aerial hemiparasitism.

Here, we present a high-quality, chromosome-level genome assembly of S. parasitica using PacBio high-fidelity (HiFi) and Hi-C sequencing technologies. We comprehensively annotated the genome, including repetitive sequences, protein-coding genes (PCGs), transcription factor (TF) genes, and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). This genome provides a foundational resource for future comparative genomic studies to explore the genetic mechanisms underlying the evolution of hemiparasitism in Santalales and to understand both convergent and divergent genomic adaptations across parasitic angiosperms.

Methods

Plant sample preparation

We collected plant material from an S. parasitica individual parasitizing Osmanthus fragrans grown at the Wangjiang Campus of Sichuan University in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, southwest China (Fig. 1a). The freshly harvested leaves were promptly washed in distilled water and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. Additionally, fresh flower, stem, leaf, and fruit tissues were collected from the same individual and frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq).

Genome survey

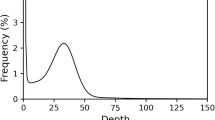

To perform genome survey analyses, we utilized an Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform for whole-genome sequencing (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Following total DNA extraction via the CTAB method18, paired-end ReSeq libraries were prepared, with an average insertion length of approximately 400 bp. A total of 39.00 Gb of Illumina reads were generated (Table 1). A 19-mer frequency distribution of these reads was generated using jellyfish v2.2.919. This analysis identified 31,259,563,762 k-mers, with a primary peak observed at a k-depth of 57 (Fig. 1b). The haploid genome size of S. parasitica was estimated to be 548.41 Mb, with a high repeat content of 64.11% and a notably low heterozygosity rate of 0.07%.

Genome assembly

For PacBio HiFi sequencing, we isolated high-molecular-weight DNA using a modified CTAB method and prepared SMRTbell libraries following the PacBio 15-kb protocol. Subsequently, circular consensus sequencing (CCS) was performed on a PacBio Sequel II sequencing platform (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA), resulting in 20.44 Gb of HiFi reads (37.3 × coverage) with an N50 length of 13,486 bp (Table 1). The HiFi long reads were processed using the CCS workflow in SMRT Link v8.0 (PacBio) and assembled into contigs using hifiasm v0.1420 with default parameters, resulting in 878 contigs totaling 552.42 Mb. To improve assembly accuracy, Illumina sequencing reads were aligned to the contigs using BWA v0.7.1721, and contigs with anomalous GC content (>50%) or insufficient coverage (<5×) were identified and removed based on the alignments. This filtering step yielded 731 contigs spanning 547.29 Mb, which were used for downstream Hi-C scaffolding analyses.

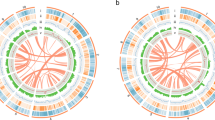

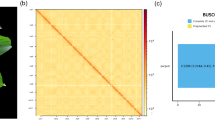

Hi-C sequencing was then performed to generate a chromosome-level genome assembly. Hi-C libraries were prepared from more than 2 g of young leaves from the same S. parasitica plant, following standard protocols for chromatin extraction, digestion, ligation, and DNA purification. Paired-end sequencing was performed on a NovaSeq 6000 sequencing platform, resulting in 63.76 Gb of Hi-C reads (116.3 × coverage) (Table 1). The Hi-C reads were mapped to the contig-level assembly using Juicebox v1.8.822. Uniquely mapped reads were subsequently used to anchor contigs into pseudochromosomes with the 3D-DNA pipeline23. Hi-C contact maps were visualized and manually curated in Juicebox to correct misassemblies (Fig. 2), yielding a final chromosome-level assembly of 547.41 Mb (Fig. 3; Table 2). In total, 97.54% (533.93 Mb) of the genome was anchored to nine pseudochromosomes, ranging from 55.41 Mb to 64.98 Mb (Fig. 3; Table 3). The contig and scaffold N50 values were 8.32 Mb and 59.61 Mb, respectively (Table 2).

Genome annotation

Genome annotation began with the identification of repetitive sequences. A de novo repeat library was constructed using Repeat Modeler v2.0.124 based on the genome assembly. This library was subsequently merged with the green plant repeat dataset from the Repbase database v22.1125. We then used RepeatMasker v4.1.026 to identify repetitive elements based on sequence homology. In total, we identified 353.26 Mb of repetitive sequences, accounting for 64.53% of the S. parasitica genome (Table 4). Among the identified repetitive elements, long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs) were the most abundant, comprising 251.45 Mb (45.93%) of the genome. Within the LTR-RT class, Gypsy and Copia elements were the most prominent, totaling 250.14 Mb. Additionally, 74.40 Mb (13.59%) of sequences were classified as unclassified repeats, suggesting the presence of species-specific or novel repeat types. Furthermore, DNA transposons accounted for 4.02% (22.01 Mb) of the genome, while long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) comprised 4.88 Mb, short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) 1.16 Mb, and other repeat types totaled 0.42 Mb (Table 4).

After masking all repetitive elements in the S. parasitica genome, we employed three complementary approaches to predict the PCGs. For transcriptome-based annotation, total RNA was extracted from all fresh tissues using the TRIzol reagent. The NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit was used to generate RNA-seq libraries after removing residual DNA. These libraries were then sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, generating 32.28 Gb of RNA-seq data (Table 1). The RNA-seq reads were de novo assembled into transcripts using Trinity v2.8.427. The resulting transcripts were aligned to the repeat-masked genome using PASA v2.3.328, and the alignment results were used to generate gene structure predictions. For homologous protein annotation, we aligned protein sequences from several representative species (Santalum album5, Malania oleifera6, Arabidopsis thaliana29, Populus trichocarpa30, Vitis vinifera31, and Theobroma cacao32) to the S. parasitica genome using TBLASTN v2.2.3133. Gene models were then predicted based on these alignments using GeneWise v2.4.134. For ab initio gene prediction, high-confidence transcripts from PASA exceeding 1,500 bp in length and containing more than two exons were selected solely to train species-specific parameters for AUGUSTUS v3.2.335. The trained AUGUSTUS model was then applied to predict genes across the entire genome without applying any length or exon-number filters, ensuring that all potential PCGs were considered. Finally, we used EvidenceModeler v1.1.136 to integrate gene models from the three approaches into a consensus, non-redundant gene set.

We predicted 21,837 PCGs in the S. parasitica genome, with 21,450 (98.23%) located on the nine pseudochromosomes at a density of 40.2 genes per Mb (Table 3). The average lengths of the predicted transcripts, coding sequences (CDSs), exons, and introns were 4,561 bp, 1,283 bp, 211 bp, and 644 bp, respectively (Table 2). To investigate potential whole-genome duplication (WGD) events, we conducted an all-against-all BLASTP search using protein sequences from S. parasitica and Santalum album. Syntenic blocks were identified using MCScanX v1.137 with default parameters, and non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates were calculated for syntenic gene pairs using the ‘add_ka_and_ks_to_collinearity.pl’ script from MCScanX. We observed a major peak around 0.73 in the Ks distribution of orthologs between S. parasitica and Santalum album, which was younger than the Ks peak of paralogs within S. parasitica (0.78), indicating that no independent WGD event occurred in the S. parasitica genome after its split from Santalum album (Fig. 4). The inter-chromosomal synteny shown in Fig. 3 therefore likely reflects ancient WGD events and more recent segmental duplications. Functional annotation, performed by aligning the protein sequences against Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL38, InterPro39, and KEGG40 databases, successfully annotated 96.05% of the genes (Table 5). We identified 1,271 TF genes (5.82% of PCGs) using PlantTFDB v5.041 (Fig. 5). Additionally, 8,407 ncRNAs with a total size of 0.98 Mb were identified by using tRNAscan-SE v2.042 for tRNAs, Infernal v1.1.243 for miRNAs and snRNAs, and BLASTN v2.2.31 against Rfam database44 for rRNAs, comprising 3,821 tRNAs, 3,076 snRNAs, 1,447 rRNAs, and 63 miRNAs (Table 6).

Data Records

The genome assembly of S. parasitica and the associated raw sequence data were made publicly available through the NCBI database under BioProject PRJNA126687745. The genome assembly is available in GenBank under accession number JBPAPV00000000046. Raw sequencing data, including Illumina, PacBio HiFi, and Hi-C reads, are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession numbers SRR3375597247, SRR3377632748 and SRR3367619549, respectively. RNA-seq reads were deposited under the SRA accession numbers SRR33745685–SRR3374568850,51,52,53. Genome assembly and annotations of repetitive elements, gene structures, and functional features have also been archived in Figshare54.

Technical Validation

We employed a variety of approaches and metrics to determine the integrity and accuracy of the final S. parasitica genome assembly. First, using BUSCO v3.0.2 software55, we evaluated the presence of 1614 conserved genes from the Embryophyta odb10 dataset. The results showed that 93.87% of complete BUSCO genes were identified at the assembly level, while 89.59% were detected at the protein level (Table 2). Second, we assessed assembly continuity by calculating the long terminal repeat (LTR) Assembly Index (LAI) using LTR_retriever v2.856. The assembly achieved an overall LAI score of 15.93, indicating reference-level genome quality (Table 2). Third, Illumina short-read data were mapped to the final assembly using BWA software. The Illumina reads covered 99.96% of the genome, with a mapping rate of 99.69% and a minimum 20-fold coverage of 99.58% of the assembly. Finally, we examined the presence of Arabidopsis-type telomeres (TTTAGGG)n57 at the ends of each pseudochromosome, with a minimum need of 5 replicates. Seven of the nine pseudochromosomes contained telomeric sequences at both ends (Table 7). Based on this comprehensive set of evidence, we conclude that the S. parasitica genome assembly is of high quality and utility.

Data availability

The genome assembly of S. parasitica has been deposited in GenBank under accession number JBPAPV000000000. All associated raw sequencing data, including Illumina, PacBio HiFi, Hi-C, and RNA-seq reads, are available under NCBI BioProject PRJNA1266877. Genome assembly and annotations have also been archived in Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29210405.v2).

Code availability

No specific script was generated in this study. All commands and pipelines for data analyses followed the manuals and protocols of the relevant bioinformatics software.

References

Westwood, J. H., Yoder, J. I., Timko, M. P. & Depamphilis, C. W. The evolution of parasitism in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 227–235 (2010).

Pennings, S. C. & Callaway, R. M. Parasitic plants: parallels and contrasts with herbivores. Oecologia. 131, 479–489 (2002).

Twyford, A. D. Parasitic plants. Curr Biol. 28, 847–870 (2018).

Nickrent, D. L. Parasitic angiosperms: how often and how many? Taxon 69, 5–27 (2020).

Mahesh, H. B. et al. Multi-omics driven assembly and annotation of the sandalwood (Santalum album) genome. Plant Physiol. 176, 2772–2788 (2018).

Hong, Z. et al. Chromosome-level genome assemblies from two sandalwood species provide insights into the evolution of the Santalales. Commun Biol. 6, 587 (2023).

Yoshida, S. et al. Genome sequence of Striga asiatica provides insight into the evolution of plant parasitism. Curr Biol. 29, 3041–3052 (2019).

Cui, S. et al. Ethylene signaling mediates host invasion by parasitic plants. Sci Adv. 6, eabc2385 (2020).

Jin, J. & Eaton, D. A. R. Pedicularis Cranolopha Genome Reference Project. (2022).

Vogel, A. Footprints of parasitism in the genome of the parasitic flowering plant Cuscuta campestris. Nat Commun 9, 2515 (2018).

Sun, G. et al. Large-scale gene losses underlie the genome evolution of parasitic plant Cuscuta australis. Nat Commun 9, 2683 (2018).

Xu, Y. et al. Comparative genomics of orobanchaceous species with different parasitic lifestyles reveals the origin and stepwise evolution of plant parasitism. Mol Plant. 15, 1384–1399 (2022).

Cai, L. et al. Deeply altered genome architecture in the endoparasitic flowering plant Sapria himalayana Griff. (Rafflesiaceae). Curr Biol. 31, 1002–1011 (2021).

Guo, X. et al. The Sapria himalayana genome provides new insights into the lifestyle of endoparasitic plants. BMC biology 21, 134 (2023).

Nickrent, D. L. Santalales (Mistletoe). Encyclopedia of Life Sciences; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA (2002).

Watson, D. M., McLellan, R. C. & Fontúrbel, F. E. Functional roles of parasitic plants in a warming world. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 53, 25–45 (2022).

Ma, R. et al. Generalist mistletoes and their hosts and potential hosts in an urban area in southwest China. Urban For Urban Green. 53, 126717 (2020).

Doyle, J. J. & Doyle, J. L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytoch. Bull. 19, 11–15 (1987).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C. & Pevzner, P. A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, i351–i358 (2005).

Jurka, J. et al. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet Genome Res. 110, 462–467 (2005).

Tarailo‐Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 5, 4–10 (2004).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494–1512 (2013).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–5666 (2003).

The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408, 796–815 (2000).

Tuskan, G. A. et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science 313, 1596–1604 (2006).

Shi, X. et al. The complete reference genome for grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) genetics and breeding. Horticult Res. 10, uhad061 (2023).

Argout, X. et al. The genome of Theobroma cacao. Nat Genet. 43, 101–108 (2011).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 1–9 (2009).

Birney, E., Clamp, M. & Durbin, R. GeneWise and GenomeWise. Genome Res. 14, 988–995 (2004).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W435–W439 (2006).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 9, 1–22 (2008).

Wang, Y. et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e49 (2012).

Bairoch, A. & Apweiler, R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 45–48 (2000).

Hunter, S. et al. InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D211–D215 (2009).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Jin, J. et al. PlantTFDB 4.0: toward a central hub for transcription factors and regulatory interactions in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D1040–D1045 (2017).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964 (1997).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

Kalvari, I. et al. Rfam 14: expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microRNA families. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D192–D200 (2021).

NCBI BioProject https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1266877 (2025).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_051363255.1 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33755972 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33776327 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33676195 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33745685 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33745686 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33745687 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR33745688 (2025).

Wang, M. Chromosome-level genome assembly of a hemiparasitic plant, Scurrula parasitica (Loranthaceae). Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29210405.v2 (2025).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422 (2018).

Riha, K. & Shippen, D. E. Telomere structure, function and maintenance in Arabidopsis. Chromosome Res. 11, 263–275 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This research was jointly funded by China’s National Natural Science Foundation (U24A20355) and the National Key Research & Development Program of China (2016YFD0600203).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.M. and M.W. designed the study. M.W, P.D, J.L. and Q.H. performed the data analyses and drafted the manuscript. Q.H., K.M., R.M., and N.M. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, M., Du, P., Liu, J. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of a hemiparasitic plant, Scurrula parasitica (Loranthaceae). Sci Data 12, 1802 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06107-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06107-0