Abstract

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) defines Critical Habitat in Performance Standard 6 (PS6) as high biodiversity value areas requiring net biodiversity gain for projects. We present an updated global screening layer of Critical Habitat aligned with IFC’s 2019 guidance. This layer derives from global datasets covering 54 biodiversity features, categorized as ‘Likely’ or ‘Potential’ Critical Habitat based on alignment with IFC criteria and data suitability. Analysis indicates 53.95 million km2 (10.58%) and 13.71 million km2 (2.69%) of the globe can be considered Likely and Potential Critical Habitat respectively, with the remaining 86.73% not overlapping with assessed biodiversity features. This represents a significant increase over previous efforts but likely remains a significant underestimation of actual Critical Habitat. Likely Critical Habitat was dominated by Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas, Intact Forest Landscapes, and protected areas; Potential Critical Habitat by Important Marine Mammal Areas and ranges of IUCN Vulnerable species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

More than US$ 60 trillion of infrastructure spending is likely required to meet 2040 societal goals, with an additional 1.2 million km2 urbanised land by 2030, an additional 3–4.7 million km of roads by 20501,2,3. Despite the relatively modest infrastructure expansion of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, biodiversity has continued to decline precipitously, with governments collectively failing every single one of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets set under the United Nations (UN) Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 2011. Much of the potential infrastructure is predicted to be newly built in some of the world’s highest integrity ecosystems, potentially leading to even greater declines in biodiversity globally4,5,6,7.

In 2012, the International Finance Corporation (IFC; a member of the World Bank Group) revised their Performance Standard 6: Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Management of Living Natural Resources (hereafter PS6), one of eight Performance Standards any client of the organisation must meet throughout the life of an investment8. PS6 draws heavily on fundamental conservation principles such as protected areas and threatened species9,10,11. The standard is seen as the benchmark for sustainable investment with 130 financial institutions following its social and environmental classification process as signatories to the Equator Principles12. Businesses can prioritise impact avoidance and direct corporate nature action with Critical Habitat screening13, even more important when, for example, half of marine Critical Habitat identified in 2015 is not formally protected and would not be flagged when only considering legally designated sites14.

Critical Habitat is defined by IFC using the following criteria:

-

1.

Critically Endangered or Endangered species

-

2.

Endemic and/or restricted-range species

-

3.

Globally significant concentration of migratory or congregatory species

-

4.

Highly threatened and/or unique ecosystems

-

5.

Key evolutionary processes

Previous work by Martin et al.15 and Brauneder et al.16 produced global 1 km2 IFC Critical Habitat screening layers for the marine and terrestrial realms respectively. These studies identified global biodiversity feature data with sufficient resolution and alignment with IFC PS6 criteria to produce global screening layers for Likely and Potential Critical Habitat. Martin et al. classified 1.6% of the ocean as Likely Critical Habitat and 2.1% as Potential Critical Habitat. Brauneder et al. 16 identified 10% of the terrestrial surface as Likely Critical Habitat and 5% as Potential Critical Habitat. The screening layers, as well as the amalgamated marine plus terrestrial Critical Habitat layer, are made available through the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre’s data portal (https://data-gis.unep-wcmc.org/portal/home/) as well as the UN Biodiversity Lab (https://unbiodiversitylab.org/en/). The layers have been used in a number of subsequent studies, including analysis of the impact of PS6 on biodiversity offset implementation17. Many of the studies focus on the threat to biodiversity of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a programme to link sixty-five countries with a network of transport and energy infrastructure. Researchers have used the global Critical Habitat screening layer to estimate that 50% of loans intersect with Critical Habitat18. Reference to Critical Habitat in this manuscript refers specifically to Likely or Potential Critical Habitat. This does not indicate confirmed Critical Habitat, which requires ground-truthed assessment. In total, 49 Chinese-funded dams have 149 km2 Critical Habitat in close proximity (i.e. within 1 km), whereas dams funded by multilateral development banks (MDBs), with binding biodiversity safeguards, have much lower average areas of Critical Habitat per area of dam at risk19. Researchers have also identified 12,000 km2 of Critical Habitat within 1 km of the Belt and Road Initiative’s linear infrastructure20. In a decarbonising world where demand for minerals is likely to increase, 20% of mining locations in Africa trigger a Critical Habitat classification for something other than Great Ape habitat21.

In June 2019, IFC updated the 2012 PS6 Guidance Note that had accompanied the initial release22. The update significantly changed the Critical Habitat criteria to better align the standard with the then newly developed Global Standard for the Identification of Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs), Table 1. This meant that the original Critical Habitat global screening layers were now out of out of data with respect to the latest criteria. At the same time, many of the datasets that underpinned the original analyses have been updated multiple times (e.g. the World Database on Protected Areas – WDPA – is updated monthly). Finally, many new datasets have been produced over recent years that meet the completeness and alignment criteria of the layer.

For businesses to manage their biodiversity impacts in areas of high biodiversity value, an updated Critical Habitat layer is required that fully aligns with the 2019 update of PS6. In this Data Descriptor, we present such a layer, which incorporates updated datasets, as well as new data sources identified through a comprehensive search against the eligibility criteria. We also describe and make available a methodology whereby the layer can be updated as and when new data are found or updated.

Methods

Critical Habitat criteria

IFC define Critical Habitat according to five criteria (Table 1) with associated thresholds for Criteria 1-4. The 2019 update to the accompanying Guidance Note made several changes to the classification of Critical Habitat of relevance to any updated methodology:

-

Changes to thresholds: thresholds have been updated to better align with the Global KBA Standard23. Criteria 1, 3 and 4 now directly align with the standard, and Criteria 1-3 have streamlined thresholds that largely sit between the previous Tier 1 and Tier 2 thresholds. Quantitative thresholds have been added for Criterion 4, based on the developing IUCN Red List of Ecosystems24.

-

Specified exceptional circumstances: IFC now specify three circumstances that trigger special considerations.

-

Great Apes: the presence of Great Ape species is likely to trigger Critical Habitat regardless of thresholds. Where present, clients are expected to inform both IFC and the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Primate Specialist Group.

-

Unapprovable sites:

-

World Heritage Sites (Natural or Mixed).

-

Alliance for Zero Extinction sites.

-

-

-

Addition of IUCN Vulnerable species: IFC added a threshold for Criteria 1 that now explicitly includes species classified as Vulnerable (VU) by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (hereafter IUCN Red List) where:

-

Globally important populations are present.

-

The loss of the population would lead to the species being upgraded to Endangered (EN) or Critically Endangered (CR).

-

The population in question would then trigger Criterion 1a (the area supports > = 0.5% of the global population and >= 5 reproductive units).

-

Data screening and classification

Using the updated criteria, we proceeded with data screening and classification as with previous studies15,16. Datasets were identified through expert knowledge and consultation, using the criteria adapted from Martin et al.:

-

1.

Direct relevance to one or more Critical Habitat criteria.

-

2.

Global in extent.

-

3.

Assembled using a standardised protocol.

-

4.

The best available data for the biodiversity feature of interest.

-

5.

Sufficiently high resolution to indicate presence of biodiversity on the ground at scales relevant to business operations.

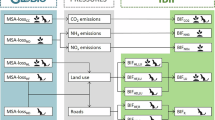

Datasets that met our criteria were classified as one of three classes: Likely, Potential, and Unclassified. The classification was done by expert judgement, weighing the alignment with PS6 criteria and the likely presence on the ground (Fig. 1). Justifications for the inclusion of individual datasets can be found in Supplementary Information.

Classification of data as Likely or Potential Critical Habitat is based on the perceived strength of alignment with PS6 criteria and the spatial resolution of the data. Adapted from Brauneder et al.16.

We identified 22 biodiversity feature datasets that are split into 54 separate triggers. Table 2 presents these datasets, with references pointing to where the data can be downloaded and notes denoting whether the data are new for this version or only available on request from data providers. Two datasets, the World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas and the IUCN Red List, are only available under a CC BY-NC licence on request from, respectively, the IUCN Red List GIS team (see https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/spatial-data-download for data and https://www.iucnredlist.org/terms/terms-of-use indicating no commercial use) and BirdLife International, on behalf of the KBA Partnership (https://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/kba-data/request for data and https://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/termsofservice indicating no commercial use).

Data processing and spatial analysis

Spatial data analysis was conducted in R, predominantly using the terra and sf packages.

For the greatest accuracy, vector data were processed using the sf package and S2 library. This allows spatial processing, e.g. intersections and buffers, using Great Circle distances. Data were prepared for the analysis in three steps: First, data were made valid on the sphere. Second, data were filtered as detailed by (a) their respective guidance, and (b) to produce the data subset required for the analysis. For example, Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) must first be filtered by those whose status is confirmed (KbaStatus = “confirmed”) and then by the criterion/criteria required to create the subset (e.g. sites designated under KBA Criterion B1). Finally, data were unioned to remove duplicates from point data and any overlapping area in polygon data. Not all input data were available in vector format. For raster data, preprocessing varies by source but generally involved aggregating to the correct resolution (30 arcseconds) before reprojecting the data to a template raster in WGS 84.

Data are then converted to binary maps of presence/absence. For vector data, this was done by a process called rasterisation, whereby any grid cell in contact with the vector data assumes the value of the vector data. In keeping with the precautionary nature of the screening layer, we chose to rasterise based on any intersection, not requiring polygon data to cross the midpoint of the grid cell. Point data transferred their values to the grid cells they occupy. For raster data, where necessary (i.e. the data were not already binary), a classification threshold was set. Again, in keeping with the precautionary nature of the data, we set this at 0.5. This meant that any cell with >= 50% of the feature was classified as a presence (see Technical Validation for a brief sensitivity analysis of this threshold).

Binary raster data were then combined so that each grid cell’s unique combination of biodiversity features has a unique value. Based on what features comprised the value, the grid cell was categorised hierarchically: Likely > Potential > Unclassified.

Data Records

The dataset is available through the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre’s data portal (https://data-gis.unep-wcmc.org/portal/home/).

These data are presented in two formats at 30 arcseconds resolution in WGS 84 projection and one in WGS 84 vector format. They represent the best publicly available global screening layer for Critical Habitat:

Basic Critical Habitat layer25

Basic_Critical_Habitat_2025.tif

Basic global layer at 30 arcseconds resolution in WGS 84 projection containing three values: 0 (Unclassified), 1 (Potential Critical Habitat), and 10 (Likely Critical Habitat). Made available under a CC BY licence at https://doi.org/10.34892/snwv-a025.

Drill down Critical Habitat layer26

Drill_Down_Critical_Habitat_2025.tif and Drill_Down_Critical_Habitat_2025.tif.vat.dbf

More detailed global layer at 30 arcseconds resolution in WGS 84 projection. The spatial grid (Drill_Down_Critical_Habitat_2025.tif) works in conjunction with the raster attribute table (RAT: Drill_Down_Critical_Habitat.tif.vat_2025.dbf) to detail what biodiversity features trigger any cell’s Critical Habitat classification. Values in the TIFF file correspond to unique identifiers in the RAT that reveal the underlying data (Table 3). Made available under a CC BY-NC licence at https://doi.org/10.34892/d3xm-qm60.

Drill down Critical Habitat layer - polygons26

Drill_Down_Critical_Habitat_Polygons_2025.gpkg

This polygonised version of the drill down raster layer allows for more concise information retention (Table 4). The data draw boundaries around the cells of each unique feature combination. For ease, and to limit the size of the file, we excluded Unclassified polygons. There are 20,340 polygons in the GeoPackage. Made available under a CC BY-NC licence at https://doi.org/10.34892/d3xm-qm60.

Data Overview

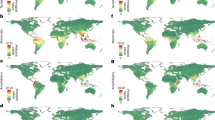

We find that 67.66 million km2 of the Earth’s surface was classified as Likely or Potential Critical Habitat (Fig. 2): 53.95 million km2 (10.58%) as Likely Critical Habitat and 13.71 million km2 (2.69%) as Potential Critical Habitat. This is a significant increase on the 25.78 million km2 (5.05%) and 10.1 million km2 (1.98%) previously identified. The remaining 442.4 million km2 (86.73%) is “Unclassified” as either known biodiversity features do not align with the IFC definition or because appropriate data that might be used to classify do not exist: Critical Habitat may still occur in these regions.

Technical Validation

Coverage

Both categories of Critical Habitat increased their absolute areas relative to the first global screening layer. Likely Critical Habitat maintained a largely similar split proportionally across domains (Table 5) but Potential Critical Habitat coverage increased in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ) relative to land and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). Overall, the updated screening layer increased coverage in all domains, with a large increase from 1.10% to 3.70% in ABNJ, 8.02% to 13.84% in EEZ and 15.09% to 27.22% on land.

Changes to the area of Potential or Likely Critical Habitat exhibit distinct regional patterns (Fig. 3). Subregions, as defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), with the most changes to coverage are the Caribbean, Central Africa, South-East Asia, South America, and remote islands near or in the Southern Ocean (Fig. 3d). States (including associated territories) with the largest areas of Critical Habitat are shown in Table 6.

Regional trends in changes to the area of Likely or Potential Critical Habitat, reprojected to Equal Earth projection and shown as a percentage of each subregion’s area. Data uses subregions of the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) from Brooks et al.65. Land, Exclusive Economic Zones and Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction are calculated separately. Plots show (a) IPBES regions and subregions; (b) Likely or Potential Critical Habitat removed in this update; (c) downgraded; (d) no change; (e) upgraded; and (f) added. Note different scales.

Table 7 sets out the coverage of the Critical Habitat screening layer across the five criteria. Criteria 1, 3, and 4 dominate coverage. As identified previously15,16, data are still either largely unavailable or do not meet Criterion 5, key evolutionary processes, and all biodiversity features triggering it remain in the marine realm. The ongoing development and improved coverage of the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems will likely serve to harmonise much of the data inputs to Criterion 4 and reduce the percentage contribution of Criterion 4 to Likely and Potential Critical Habitat classifications24,27.

Large species ranges

The inclusion of species classified as Vulnerable in the IFC Guidance Note 2019 update, and data updates to the IUCN Red List generally, necessitated the inclusion of large numbers of species ranges. Some of these ranges, e.g. the Australian grey falcon, Falco hypoleucos, are exceptionally large. To retain precision in the updated screening layer, we conducted a sensitivity analysis of trimming the largest species ranges (range areas 3, 10, 20 and 50 standard deviations above the mean; see Fig. 4 below). Trimming species ranges 3 standard deviations above the mean resulted in a 61.2% decrease in coverage for the removal of only 31 species ranges out of 3,953. Furthermore, among the species ranges excluded were the northern white rhino, Ceratotherium simum cottoni, whose species range spans several Central and Eastern African countries despite comprising only two living individuals, and the ivory-billed woodpecker, Campephilus principalis, which may be extinct. Species are not expected to be evenly distributed within this range and if it is otherwise important for threatened species it will likely be classified as Critical Habitat via other biodiversity features.

Presence thresholds

Following Martin et al.15 and Brauneder et al.16, we use a high threshold for species distribution models of >90% as for the modelled cold-water coral datasets used in this analysis (Table 2; see also Fig. 8). However, two datasets, tropical moist forest and mangroves, required an alternative approach as they represent high-resolution data (10 or 30 m grid cells) derived from satellite imagery28,29. The 10 or 30 m pixels are classified as presence/absence. When averaged to 30 arcseconds resolution, these data then present an effective percentage cover in the cell. Figure 5 below shows the result of applying four different thresholds to these data: 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 0.9. As the aggregated data do not constitute a probability distribution, we selected ≥ 0.5 as the threshold. For mangroves, the area occupied by 1 km cells over this threshold approximated the reported global extent of mangroves28.

Feature coverage vs previous screening layer

In our updated Critical Habitat screening layer, 38.03 million km2 has been added, 4.558 million km2 upgraded, 0.2585 million km2 downgraded, and 6.246 million km2 removed. This represents a significant expansion of area over previous efforts but likely remains an underestimation of actual Critical Habitat worldwide. This is due in part to the strict data screening criteria we set (Methods), but also a genuine lack of data for many biodiversity features. Tables 8, 9, 10 and 11 detail the biodiversity features responsible for the changes. Figure 6 shows the composition of each biodiversity feature.

Important Marine Mammal Areas (IMMAs) dominate contributions to added Potential and Likely Critical Habitat (Table 8), adding 11.37 million km2 for IMMAs designated under criteria C1, C2 and C3 alone. Intact Forest Landscapes, an extensive biodiversity feature added in the update (see Supplementary Information for their inclusion justification), also contributes a significant area. For areas upgraded from Potential Critical Habitat to Likely Critical Habitat (Table 9), forest features dominate: over half of the area upgraded contain areas that are Likely Critical Habitat due to the presence of tropical moist forest. Just under half of all areas upgraded were previously Potential Critical Habitat due to the presence of tropical dry forest.

Areas downgraded or removed from the screening layer tend to be an order of magnitude lower than those upgraded or added (Tables 10 and 11). Some of the features shown to have had area removed in the update are derived from the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) and World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas (WDKBA), two datasets that are regularly updated, with records both added and removed. Protected areas, for example, are often downgraded, downsized, or even degazetted and these changes would be reflected in the screening layer30. However, some features used the same data as previously, which warranted further inspection: 43.69% of tropical dry forest has been removed from the layer, alongside 38.81% of cold-water coral. Both appear to be small errors in the production of the previous screening layer. Figure 7 shows a comparison between the original input data, used in this layer and previously, alongside how the data were aggregated to a lower resolution in the previous layer and now. The method employed here appears to better reflect the higher resolution data but would reduce the overall feature area when compared to previously. For octocorals, the previous methodology considered values of >90% as presences for the species distribution models, but Fig. 8 shows that it is more likely that the analysis classified cells ≥90% as presences. In this update, we have maintained a threshold of >90%, which has consequently removed some areas from the layer.

Usage Notes

As noted by Martin et al.15 and Brauneder et al.16, the global Critical Habitat screening layer does not replace detailed on-the-ground Critical Habitat assessments. Reference to Critical Habitat here refers specifically to areas in the screening layer identified as Likely or Potential Critical Habitat, and does not indicate confirmed, on-the-ground, Critical Habitat. The data allow users to identify areas that need further investigation, including full Critical Habitat assessment, and to help direct impact mitigation efforts and conservation action.

We recommend working mostly with the raster data. While the polygon layer allows for more information to be stored about the relevant biodiversity triggers, it is susceptible to misuse if users mistake it for actual vector data and start performing advanced spatial operations on the layer.

Due to precision restrictions inherent with R, the number of biodiversity feature triggers that this workflow can handle is ~66 (this analysis uses 54, see Table 2).

Data availability

All data described in this Data Descriptor are available on the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre’s data portal (https://data-gis.unep-wcmc.org/portal/home/):

• The basic layer25, Basic_Critical_Habitat_2025.tif, identifying 30 arcsecond grid cells that are either Likely Critical Habitat, Potential Critical Habitat or Unclassified, is available for download here: https://doi.org/10.34892/snwv-a025.

• The drill down layer26, identifying both 30 arcsecond grid cells that are either Likely Critical Habitat, Potential Critical Habitat or Unclassified, as well as which biodiversity feature triggered any of the five criteria (Table 1), are available at https://doi.org/10.34892/d3xm-qm60 in two formats:

⚬ Raster (Drill_Down_Critical_Habitat_2025.tif and Drill_Down_Critical_Habitat_2025.tif.vat.dbf, see Table 3 for a description of the variables included); and

⚬ Polygon (Drill_Down_Critical_Habitat_Polygons_2025.gpkg, see Table 4).

The data download, WCMC_043_GlobalCH_IFCPS6_2025, contains three subfolders and a short README file:

1. 01_Data: data files outlined above;

2. 02_Resources: relevant literature providing further information on IFC PS6; and

3. 04_Map: a simple global representation of the data in a .jpg plot.

The basic layer is made available under a CC BY licence whereas the drill down layers are made available under a CC BY-NC licence.

Code availability

The code used to compile this update of the global Critical Habitat screening layer is publicly available through the Zenodo repository31. The analysis is split across seven R scripts:

• 0 spatial_processing_functions.R. Provides custom spatial processing functions required (see Methods).

• 1.1 Red_List_Preprocessing.R. Initial processing of the IUCN Red List data, including filtering out species ranges with areas larger than a set amount of standard deviations above the mean (see Technical Validation).

•1.2 Data_Preprocessing_Raster.R. Preprocessing for the few datasets not available in vector format to produce standardised binary rasters for the next stage of the analysis.

•1.3 Data_Preprocessing_Vector.R. Preprocessing for vector input datasets to produce flat, dissolved layers for the next stage of the analysis.

• 2 Create_Drill_Down_Critical_Habitat_Raster_Layer.R. Contains the lion’s share of processing. Converts the input flat vector layers to binary raster data and combines with the existing binary raster data in a process akin to the Combine tool in ArcGIS to produce a layer with a unique value for every resultant combination of input datasets. The script also produces the accompanying raster attribute table (RAT).

• 3 Create_Basic_Critical_Habitat_Raster_Layer.R. Converts the detailed raster data into the basic Critical Habitat file.

• 4 Create_Drill_Down_Polygons.R. Polygonises the drill down raster data to produce a vector layer that allows more information to be stored in the file than allowed in the spatial grid + RAT.

References

Meijer, J. R., Huijbregts, M. A. J., Schotten, K. C. G. J. & Schipper, A. M. Global patterns of current and future road infrastructure. Environmental Research Letters 13, 064006 (2018).

Seto, K. C., Güneralp, B. & Hutyra, L. R. Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 16083–16088 (2012).

Global Infrastructure Hub. Global Infrastructure Outlook (2017).

Laurance, W. F. et al. Reducing the global environmental impacts of rapid infrastructure expansion. Current Biology 25, R259–R262 (2015).

Latrubesse, E. M. et al. Damming the rivers of the Amazon basin. Nature 546, 363–369 (2017).

Alamgir, M. et al. High-risk infrastructure projects pose imminent threats to forests in Indonesian Borneo. Sci Rep 9, 140 (2019).

Zu Ermgassen, S. O. S. E., Utamiputri, P., Bennun, L., Edwards, S. & Bull, J. W. The Role of “No Net Loss” Policies in Conserving Biodiversity Threatened by the Global Infrastructure Boom. One Earth 1, 305–315 (2019).

International Finance Corporation. Performance Standard 6: Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Management of Living Natural Resources (2012).

UNEP-WCMC and IUCN. Protected Planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) [Online], Cambridge, UK: UNEP-WCMC and IUCN. (2025).

IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2025-1. https://www.iucnredlist.org. (2025).

Bingham, H. C. et al. Sixty years of tracking conservation progress using the World Database on Protected Areas. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 737–743 (2019).

Equator Principles Association. Signatories & EPFI Reporting. Equator Principles https://equator-principles.com/signatories-epfis-reporting/ (2024).

Addison, P. F. E., Bull, J. W. & Milner-Gulland, E. J. Using conservation science to advance corporate biodiversity accountability. Conservation Biology 33, 307–318 (2019).

Jacob, C. et al. Marine biodiversity offsets: Pragmatic approaches toward better conservation outcomes. Conservation Letters 13, e12711 (2020).

Martin, C. S. et al. A global map to aid the identification and screening of critical habitat for marine industries. Marine Policy 53, 45–53 (2015).

Brauneder, K. M. et al. Global screening for Critical Habitat in the terrestrial realm. PLoS ONE 13, e0193102 (2018).

Bull, J. W. & Strange, N. The global extent of biodiversity offset implementation under no net loss policies. Nat Sustain 1, 790–798 (2018).

Yang, H. et al. Risks to global biodiversity and Indigenous lands from China’s overseas development finance. Nat Ecol Evol 5, 1520–1529 (2021).

Narain, D., Teo, H. C., Lechner, A. M., Watson, J. E. M. & Maron, M. Biodiversity risks and safeguards of China’s hydropower financing in Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries. One Earth 5, 1019–1029 (2022).

Narain, D., Maron, M., Teo, H. C., Hussey, K. & Lechner, A. M. Best-practice biodiversity safeguards for Belt and Road Initiative’s financiers. Nat Sustain 3, 650–657 (2020).

Junker, J. et al. Threat of mining to African great apes. Science Advances 10, eadl0335 (2024).

International Finance Corporation. International Finance Corporation’s Guidance Note 6: Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Management of Living Natural Resources (2019).

IUCN. A Global Standard for the Identification of Key Biodiversity Areas, Version 1.0. (2016).

IUCN. Red List of Ecosystems | Home. https://www.iucnrle.org/ (2024).

UNEP-WCMC. Global Critical Habitat Screening Layer - Basic. UNEP-WCMC https://doi.org/10.34892/SNWV-A025 (2025).

UNEP-WCMC. Global Critical Habitat Screening Layer - Drill. UNEP-WCMC https://doi.org/10.34892/D3XM-QM60 (2025).

Nicholson, E. et al. Roles of the Red List of Ecosystems in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Nat Ecol Evol 8, 614–621 (2024).

Bunting, P. et al. Global Mangrove Watch (1996 - 2020) Version 3.0 Dataset. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.6894273 (2022).

Vancutsem, C. et al. Long-term (1990–2019) monitoring of forest cover changes in the humid tropics. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe1603 (2021).

Golden Kroner, R. E. et al. The uncertain future of protected lands and waters. Science 364, 881–886 (2019).

Dunnett, S. et al. An update to the global Critical Habitat screening layer. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.13912845 (2025).

UNEP-WCMC. International Finance Corporation Performance Standard 6 Implications of the November 2018 update to Guidance Note 6 (2019).

Ramirez-Llodra, E., Blanco, M. & Arcas, A. ChEssBase: an online information system on biodiversity and biogeography of deep-sea chemosynthetic ecosystems (2004).

UNEP-WCMC. Global Distribution of Cold Seeps (2010) (2023).

Davies, A. J. & Guinotte, J. M. Global Habitat Suitability for Framework-Forming Cold-Water Corals. PLoS ONE 6, e18483 (2011).

Yesson, C. et al. Global habitat suitability of cold‐water octocorals. Journal of Biogeography 39, 1278–1292 (2012).

Yesson, C. et al. Global raster maps indicating the habitat suitability for 7 suborders of cold water octocorals (Octocorallia found deeper than 50m). unknown PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.775081 (2012).

Freiwald, A. et al. Global distribution of cold-water corals (version 5.1). Fifth update to the dataset in Freiwald et al. (2004) by UNEP-WCMC, in collaboration with Andre Freiwald and John Guinotte. UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre, https://doi.org/10.34892/72x9-rt61 (2021).

Underwood, E. C., Olson, D., Hollander, A. D. & Quinn, J. F. Ever-wet tropical forests as biodiversity refuges. Nature Clim Change 4, 740–741 (2014).

Lumbierres, M. et al. Area of Habitat maps for the world’s terrestrial birds and mammals. Sci Data 9, 749 (2022).

Lumbierres, M. et al. Area of Habitat maps for the world’s terrestrial birds and mammals. 295372887888 bytes. Dryad https://doi.org/10.5061/DRYAD.02V6WWQ48 (2022).

Beaulieu, S. E. & Szafrański, K. M. InterRidge Global Database of Active Submarine Hydrothermal Vent Fields Version 3.4. 20 data points. PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.917894 (2020).

BirdLife International. Digital boundaries of Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas from the World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas (2023).

IUCN-MMPATF. Global Dataset of Important Marine Mammal Areas (IUCN-IMMA). Made available under agreement on terms and conditions of use by the IUCN Joint SSC/WCPA Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force (2023).

Potapov, P. et al. The last frontiers of wilderness: Tracking loss of intact forest landscapes from 2000 to 2013. Sci. Adv. 3, e1600821 (2017).

Greenpeace, University of Maryland, World Resources Institute, & Transparent World. Intact Forest Landscapes. 2000/2013/2016/2020. Global Forest Watch.

Le Saout, S. et al. Protected Areas and Effective Biodiversity Conservation. Science 342, 803–805 (2013).

BirdLife International. The World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas. Developed by the KBA Partnership: BirdLife International, International Union for the Conservation of Nature, Amphibian Survival Alliance, Conservation International, Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, Global Environment Facility, Re:wild, NatureServe, Rainforest Trust, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Wildlife Conservation Society and World Wildlife Fund. Available at http://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/ [Accessed 25/04/2025]. (2025).

Bunting, P. et al. Global Mangrove Extent Change 1996–2020: Global Mangrove Watch Version 3.0. Remote Sensing 14, 3657 (2022).

Mcowen, C. et al. A global map of saltmarshes. BDJ 5, e11764 (2017).

Mcowen, C. et al. Global Distribution of Saltmarsh. 2.11 GB United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) https://doi.org/10.34892/07VK-WS51 (2017).

Kot, C. et al. The State of the World’s Sea Turtles Online Database: Data provided by the SWOT Team and hosted on OBIS-SEAMAP (2020).

Halpin, P. et al. OBIS-SEAMAP: The World Data Center for Marine Mammal, Sea Bird, and Sea Turtle Distributions. Oceanog 22, 104–115 (2009).

UNEP-WCMC & Short, F. T. Global Distribution of Seagrasses. 853 MB (polygons), 21 MB (points) United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) https://doi.org/10.34892/X6R3-D211 (2005).

Yesson, C., Clark, M. R., Taylor, M. & Rogers, A. D. Knolls and seamounts in the world ocean - links to shape, kml and data files. 18 data points PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.757563 (2011).

Yesson, C., Clark, M. R., Taylor, M. L. & Rogers, A. D. The global distribution of seamounts based on 30 arc seconds bathymetry data. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 58, 442–453 (2011).

Sanderson, E. W. et al. Range-wide trends in tiger conservation landscapes, 2001 - 2020. Front. Conserv. Sci. 4, 1191280 (2023).

WCS - Tiger Conservation Landscapes - Open source data access. WCS - Tiger Conservation Landscapes - Open source data access https://act-green.org/data-access.

Miles, L. et al. A global overview of the conservation status of tropical dry forests. Journal of Biogeography 33, 491–505 (2006).

UNEP-WCMC. Global tropical dry forest (2024).

EC JRC. Tropical moist forest - Transition Map - Main Classes 1982-2023. (2024).

Karger, D. N., Kessler, M., Lehnert, M. & Jetz, W. Limited protection and ongoing loss of tropical cloud forest biodiversity and ecosystems worldwide. Nat Ecol Evol 5, 854–862 (2021).

Karger, D. N., Kessler, M., Lehnert, M. & Jetz, W. Limited protection and ongoing loss of tropical cloud forest biodiversity and ecosystems worldwide [2018 ensemble mean]. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01450-y (2021).

UNEP-WCMC, WorldFish, World Resources Institute, & The Nature Conservancy. Global Distribution of Coral Reefs. 1.33 GB United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) https://doi.org/10.34892/T2WK-5T34 (2010).

Brooks, T. M. et al. Analysing biodiversity and conservation knowledge products to support regional environmental assessments. Scientific Data 3, 160007 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M., A.R. and J.A.T. designed the study. A.M., A.R., J.A.T. and S.D. collected and analysed the data. S.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed substantive review and edits of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dunnett, S., Muge, A., Ross, A. et al. An update to the global Critical Habitat screening layer. Sci Data 12, 1812 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06117-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06117-y