Abstract

This data descriptor presents a decade-long agronomic dataset collected between 2012 and 2022 by extension agents across Mexico as part of CIMMYT’s on-farm experimentation network. Extension agents used a unified digital logbook platform (BEM, later e-Agrology) to record agronomic activities, farm operations, and results. After multi-stage cleaning and validation, the dataset comprises 69,008 logbooks from 10,763 innovation plots testing new technologies, 10,305 control plots under conventional management, and 47,940 extension plots adopting sustainable practices. Key variables cover crop management (including sowing and harvest dates), resource use (including inputs, fuel and labor), activity costs, market prices, and yields for maize (Zea mays), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), wheat (Triticum aestivum, Triticum durum), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), and barley (Hordeum vulgare). Spanning diverse agroecologies and farm sizes, this open-access resource enables analyses of long-term productivity trends, cost–benefit relationships, input–output efficiencies, and climate-related performance. By providing harmonized, field-level data across multiple management scenarios, it can be used to derive valuable insights for researchers, extension services, and policymakers to develop optimized agronomic recommendations and sustainable intensification strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Mexico features highly diverse and complex agroecologies with varied soil types, climate conditions, and socio-economic settings; however, average yields remain well below their potential, posing significant challenges for improving agricultural practices1. Farming systems across the country vary widely with some farmers growing traditional polycultures, while others apply modern farming techniques with high inputs2. Maize (Zea mays L.) is the national staple crop, followed by beans (Phaseolus spp.), wheat (Triticum durum and Triticum aestivum), barley (Hordeum vulgare), and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). These crops are grown in specific regions, whereas maize is grown countrywide under conditions ranging from arid plains to tropical rainforests, from sea level to almost 3,000 meters altitude, under irrigation or rainfed cropping, by smallholder farmers or large-scale commercial farmers. There are typically two growing seasons each year: Autumn–Winter (October to February) and Spring–Summer (March to September), with crops grown in either or both, depending on the region.

Climate change, including rising temperatures and more erratic rainfall, is expected to impact Mexican cereal production and strong adaptation measures will be required3. Under high-emission scenarios, crop models project yield reductions of up to 42% for rainfed maize and up to 23% for rainfed wheat by century’s end in Mexico4.

The diverse and changing conditions pose a challenge for developers of useful, locally tailored recommendations on productive and sustainable practices for cereal cropping, as substantial research and localized data are required. The lack of direct data on farming operations has hindered informed decision-making and the development of evidence-based agricultural policies, limiting crop yields and the adoption of innovations, including sustainable production practices. At the same time, Mexico’s diverse agricultural systems present an opportunity to generate rich, relevant data regarding complex challenges—both current and future—to agrifood systems in Mexico and elsewhere.

Despite the wealth of national- and regional-scale yield statistics for Mexico—such as Cierre Agrícola (maize and wheat since the 1980s) by the Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera (SIAP)5, FAOSTAT (1961–present)6, and NASA-SEDAC’s Twentieth Century Crop Statistics (1900–2017)7—there remains a critical gap in publicly accessible, plot-level agronomic records tracking dynamics over time. While studies like those in the Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas have analyzed yield variability8 and agronomic management in maize systems9,10, existing sources rarely capture the day-to-day decisions, input applications, and labor investments that drive productivity and sustainability in smallholder and commercial cereal systems11,12. This gap persists despite longitudinal efforts like Mexico’s Encuesta Nacional Agropecuaria (ENA)13.

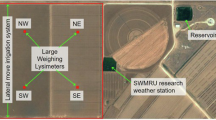

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) launched a large-scale on-farm experimentation network in Mexico in the late 2000s. Initially focused on promoting conservation agriculture (minimal soil movement, crop diversification, and permanent soil cover) for productivity gains, the network evolved to emphasize knowledge management and design thinking to make cereal production more sustainable, inclusive, productive, and profitable (for farmers)14,15. The network comprised hubs established in diverse agroecological and geographic zones and designed around plot types that varied in treatment complexity and the intensity of technical follow-up and data collection. Each hub also featured a stakeholder network of farmers, extension agents, and local governments and research institutions, collaborating to address local challenges and test locally-targeted technologies. Over more than a decade, the network grew significantly, supported by both public and private donors through more than 30 projects, and a number of the hubs continue to operate.

In 2012, CIMMYT developed a standardized digital agronomic logbook, enabling the systematic documentation of activities and relevant data from farmers across geographical and sociocultural settings. To foster the logbook’s relevance and practicality, its development was collaborative and participatory, involving agricultural experts, researchers from public and private institutions, and farmer representatives.

Observational data were collected by extension agents directly from farms throughout the cropping seasons, rather than relying on retrospective surveys that ask farmers to recall past seasons. Farmers decided directly on which agricultural innovations to try out in their fields, rather than following an imposed treatment design or controlled experiments. Both aspects were purposely chosen as part of an “innovation system” approach for the network14 and to capture a realistic view of on-farm conditions, the practical challenges farmers face, and their related decisions. The data come from three types of network plots: side-by-side treatment comparisons comprising (i) innovation plots, where farmers implemented new technologies and compared them to (ii) control plots featuring conventional practices; and (iii) extension plots, where only improved practices and technologies were tested, providing further insights into the adoption and performance of innovations without comparison to conventional practices.

The presented dataset represents a decade of network data collection (2012–22), documents the complexities of Mexico’s multi-crop systems and diverse farming conditions, and provides an extensive and valuable research resource. It documents on-farm costs, production practices, and associated outcomes, thereby detailing farmers’ challenges and opportunities. Farmers also chose which innovations to test with no payment or reward, so the data offer insights into farmer decision-making and adoption, as well as providing robust baselines for future studies and the development of evidence-based agricultural recommendations and policies.

Methods

Data collection systems (BEM and e-Agrology)

CIMMYT began collecting farmer plot data using the Bitácora Electrónica MasAgro (BEM) in 2012. Developed in-house, the BEM supported both online and offline data entry, using role-based access to structure responsibilities and data validation (Fig. 1). The BEM categorized plots into control, innovation, and extension types, as decided by the farmer each season, so the same plot could be classified as a different type in different seasons. Data could be captured from several plots for each farmer, and a unique agronomic logbook was made for each season (winter or summer) for each plot. Detailed agronomic and socioeconomic data were collected, including farmer profiles, geographic coordinates, soil preparation, crop management, and harvest details. The BEM included critical compulsory sections on sowing/planting dates and harvest and yield data, along with many optional sections (field operations, including land preparation or leveling, input applications, irrigation, and harvest methods; Fig. 1). Multiple records could be entered per field operation. For instance, users could log multiple fertilizer applications, specifying product names, amounts, costs, and application methods. If climatic conditions required a change in agronomic practices, users could adjust the entries to reflect the new management plan. The system also featured an automated function that generated additional data entry forms for planting, harvesting, yield, and fertilization, when multiple crops are reported in a given cycle.

Data validation involved a multitier review (Fig. 2), whereby extension agents recorded detailed information about agronomic activities from at least two plot visits per season. Supervisors reviewed the entries, flagged potential errors or outliers, and returned the data to the agents for correction as needed. Once finalized and approved, the logbook was locked for the season, ensuring accuracy and integrity before analysis. The BEM was thus able to generate standardized reports on yields and profitability for diverse agricultural practices and innovations.

Despite its practical success, the BEM’s reliance on the Silverlight plugin16—a technology phased out in modern browsers—prompted the development of a revamped “e-Agrology” platform in 2019. Built on HTML517, e-Agrology retained BEM’s core structure for data collection and validation but with added features to improve the user experience and system flexibility. Key updates included a redesigned mobile app with a more intuitive interface and a centralized hub for data sharing, supporting smoother data exchange for fields, user details, and project information.

For system administrators, e-Agrology featured advanced project management tools, catalog sorting based on project requirements, and a modernized interface. Administrators were able to filter projects and access multi-user permissions, temporary drafts, and data block settings, making the system more adaptable and useful for large-scale agricultural data collection. Users benefited from streamlined data entry through integrated plot and site registration. The new system supported table-based data entry, incorporating repeating blocks to simplify managing large datasets. To enhance interoperability, an Application Programming Interface (API) endpoint was introduced, enabling external applications to connect directly to the database and facilitating efficient data exchanges between e-Agrology and other software, as well as allowing external users or tools to retrieve the data without requiring direct database access18.

Data collection

Field visits and interviews

Extension agents conducted regular plot visits, according to the crop stage and plot type and with at least two visits each growing season. Side-by-side comparison fields with innovation and control plots received bi-weekly visits, while extension plots were visited monthly. Not all visits were formally documented, as some were monitoring or farmer contact check-ins, but at least two formal in-person visits were required, with follow-up phone calls as needed.

Data on inputs, costs, dosages, dates, labor, and units of measurement for each agronomic activity were collected through interviews and conversations with farmers and recorded in the logbook system. Challenges in data collection included accurately spelling active ingredient names, recording all active ingredients, especially detailing the contents of biological inputs, and estimating the costs and contents of homemade inputs. Common inputs could be chosen from a drop-down menu. Since there is a lot of diversity in inputs used and new products are constantly released, the system also accommodated the use of custom names for inputs (in the category ‘other’) and of multiple units. Costs were recorded as per-hectare.

Informed consent

Every logbook collected included an informed consent that was read to farmers before initial registration, accepted by the farmer orally, and marked as accepted by the extension agent in the BEM and/or e-Agrology data collection platforms.

Yield data collection

Yield was determined as described in CIMMYT’s guide on measuring yield and yield components, by harvesting the grain in several subsamples of a predetermined size. For maize, 3 subsamples of cobs were gathered, each subsample 10 m long and 1 row wide, recording average grain yield. Grain moisture content was typically determined using a Grain Moisture Tester (John Deere, Moline, Illinois, USA) and adjusted to 14% for maize and 12% for other crops, the common practice in Mexico. In commercially harvested extension areas, yield was registered as reported by the weighing bridge when sold, while for subsistence farmers yield in extension plots was often estimated by farmers, given that harvesting normally lasted several months.

Data quality assurance

Real-time data validation

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of data collected during the growing season, supervisors checked for outliers or unusual values, flagged them to extension agents for verification and validation (Fig. 2). Errors identified were promptly corrected, maintaining the integrity of growing season datasets and ensuring that exceptional circumstances or unexpected results were properly documented and explained.

Post-season data review

After each growing season, CIMMYT’s data analysis team conducted a comprehensive review to identify any remaining outliers or inconsistencies. Datasets were then presented to regional teams of extension agents and local CIMMYT staff for validation, thereby leveraging their collective expertise and local knowledge, providing context for unusual observations, and ensuring that the final dataset accurately reflected local realities. Discrepancies were discussed in detail, and collective decisions were made on how to address them, often guided by subject-matter experts and established data ranges.

Data cleaning and validation

The dataset presented here integrates data collected through the BEM for 2012–19 and e-Agrology for 2020–22. Many variables were consistent across systems but e-Agrology introduced new variables, requiring detailed harmonization to align the datasets. As part of this, we “mapped” the variables: identical variables were retained as-is, new variables unique to e-Agrology were added, and for variables that were similar but differed in metric or phrasing, one option was selected to maintain consistency across the dataset. The final integrated dataset was organized into six datasheet files, ensuring that all variables were accurately matched and harmonized.

Initial cleaning

Both BEM and e-Agrology operate as open platforms, allowing multiple users to contribute and collect data, increasing the likelihood of inconsistencies. To address this, duplicates, test records, and entries lacking yield data or identified as user errors during registration have been removed. An initial cleaning and validation were conducted on a dataset of 84,673 logbooks using yield data as a key filter: the presence of yield data in a logbook indicates that its data cover the full crop cycle. This filtering ensured that only complete and reliable data were retained for further analysis, resulting in 10,803 innovation plot logs, 10,892 control plot logs, and 48,037 extension plot logs—a total of 69,732 validated logbook entries (Table 1).

For key crops in the dataset (maize, barley, beans, sorghum and wheat), yield data were first cleaned and preliminary ranges set, excluding extreme values identified as user errors. Then a descriptive and exploratory analysis was conducted to assess data distribution and variability, utilizing location and variability measures (e.g., mean, median, standard deviation, etc.). Visualization (histograms and boxplots) helped detect potential outliers. Together with the expert team, accepted ranges for yield were determined, taking into account irrigation regime (rainfed vs irrigated). All ranges included zero, for instances of crop failure or total loss (Table 2). Yield records (and associated logbooks) with data outside of these ranges or with N/A as an answer in the yield field were removed. After the initial cleaning, 69,041 logbooks remained in the dataset (Table 1).

Secondary cleaning

These logbooks underwent a second cleaning and validation, which included correcting typographical and spelling errors, standardizing units, and detecting, transforming, and processing outliers. Inconsistent units were converted to a common unit with preference given to SI units and consistent terms applied for groups of similar options. For numerical data, a preliminary analysis was done in the same way as for the yield data and outliers were examined. Some outliers were adjusted to reflect plausible values based on expert feedback. Extreme values identified as user errors or beyond universally accepted scales (e.g., pH levels higher than 14) were marked as missing data for those variables. This approach ensured that the data not only met quality standards but also preserved critical information. At this stage, it was also decided to omit logbooks from control plots that did not have an innovation plot to compare with, for example when innovation plot data had been removed during initial cleaning (Table 1).

Data privacy and ethical considerations

The Institutional Research Ethics Committee of CIMMYT cleared the data collection process and the use of the dataset without any personal identifiable information under authorization number 2023-026. Informed consent was obtained from all farmers providing information. All names, phone numbers, addresses, and email information were eliminated and all coordinates associated with plots were blurred by truncating the latitude and longitude of each vertex by three decimal places, reducing the precision of each coordinate to within several hundred meters and thereby obscuring the exact location while maintaining the general shape and area and allowing for meaningful spatial analysis.

Data Records

Available online at Dataverse19, the dataset comprises six primary files that can be downloaded in XLSX and CSV formats. The files provide data on farmers, plots, agronomic practices, and outcomes over 2012–2022. File names are self-descriptive and the dataset structure ensures compatibility with standard data analysis tools; all files include headers corresponding to the collected variables. The dataset provides essential metadata, including local agricultural terminology in Spanish and English, facilitating analysis and interpretation for contextual accuracy. All files can be linked through three primary identifiers: Farmer ID, Plot ID, and Logbook ID. By linking files through identifiers, researchers can view integrated analyses across the dataset.

The first file, Farmer_Plot_Logbook_2012–2022_03.xlsx, contains data on farmer and plot characteristics. Key variables include Farmer ID, education level, gender, ethnic group, location, years of agricultural experience, plot details (e.g., area, location, land ownership, average precipitation, and temperature), and management information such as level of technification and details on innovation versus control plots, water regimes, and adopted practices.

The second file, Sowing_Harvest_Yields_2012–2022_02.xlsx, focuses on sowing and harvest data, including plot type, crop details, sowing practices, and yield data. Variables include crop variety, sowing density, arrangement, harvesting dates, along with metrics such as yield per hectare and satellite-derived plot surface area.

The third file, Labor_Harvest_Activities_2012–2022_02.xlsx, documents field operations from land preparation through harvest. It details labor inputs, tools and machinery used, power sources, fuel consumption, and work times, as well as the impacts of environmental and management factors on productivity.

The fourth file, Agricultural_Supplies_2012–2022_01.xlsx, lists agrochemical and biological inputs used for crop production, including fertilizers, pest control products, and seed treatments. Variables include input application details, product names, active ingredients, nutrient content, and quantities applied, as well as the rationale for application.

The fifth file, Irrigacion_2012–2022_01.xlsx, provides data on irrigation practices, including methods (surface sprinkler, drip), water consumption, irrigation frequency, and system details. It also records the duration of irrigation applications and the number of participants involved, to account for specific irrigation labor needs.

The sixth file, Costs_and_Revenues_2012–2022_02.xlsx, summarizes costs and income associated with all registered agricultural activities. Variables include direct and indirect expenses, total costs per hectare, and revenues.

Farmer, plot, and logbook characteristics

Farmer data

This table includes socio-demographic information such as gender, ethnicity, total area cultivated by the farmer, educational level, years of experience, and resident state and municipality. To comply with data protection laws and ethical guidelines, personal names, contact information, or other personal details have been omitted from the publicly available data set. The unique registration identifier generated by the data collection system is included so CIMMYT can link data records to the farmer’s personal information when needed.

Basic plot data

This table describes plot characteristics (legal, physical, geographical), including information from the previous growing season. Legal characteristics include land ownership (owned, rented, borrowed) and the type of property (private, communal, ejidal). Truncated plot location coordinates provide the approximate location. Surface area is derived from farmer estimates and a satellite image measuring application. Farmer observations regarding the previous season’s grain yields and crop residue cover are included, along with extension agent estimations of physical characteristics such as average annual precipitation and temperature, predominant slope and relief, soil texture, and erosion rate. This table also covers technology/technification levels.

Logbook characteristics

This table identifies the year, agricultural growing season, technologies implemented, water regime, and plot type. The plot ID is permanent, but the “type” for each plot can vary across growing seasons and logbooks.

Sowing, harvest, and yields

Sowing

Each sowing record is uniquely identified by the Crop Sowing ID and describes whether the activity was sowing vs re-sowing, seed type (hybrid, native, improved), and the local or commercial variety name. Additional details include seed color, sowing density (both unit type and quantity per hectare), and how the sowing date was chosen. Variables include plot type e.g., flat, furrow, bed), sowing pattern (planting hole, row, broadcast, intercropped), bed width, and slope, as well as the number of seeds and plants per hole and distances between plants, rows, and furrows.

Harvest

The data here are crop type harvested and yield, uniquely identified for each by Yield ID. Variables include the product (forage, fruit, seed, flowers, other), the unit used, yield per hectare, and harvest start and end dates. The dataset also contains the total plot area as stated by the farmer and as measured via satellite imagery.

Yield

Yield data collection is described above. The entire dataset includes 76 crops. Maize, beans, wheat, barley, and sorghum account for most of the yield data. There are 44,909 records for maize, 5,052 for beans and 2,876 for wheat. After those in number of records are oats (Avena sativa; 526), pumpkin (Cucurbita spp.; 465), sunflower (Helianthus annuus; 201), triticale (x Triticosecale; 177), and chickpea (Cicer arietinum; 167).

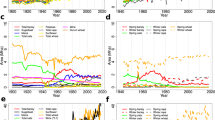

Yield data for maize come from more than 1,065 municipalities and had the widest range in average yield per municipality of all crops (from 0.2 to 17.2 t/ha; Fig. 3a). Beans are the second most widespread crop, with records from 179 municipalities from the north of the country all the way to the Yucatan peninsula, and the highest average yield per municipality was 3.2 t/ha (Fig. 3b). Wheat records were concentrated in 3 regions, with irrigated wheat in coastal municipalities in Baja California and Sonora, and the centrally located Bajio region showing municipal averages from 4.5 to 9.0 t/ha, while rainfed wheat in Zacatecas and the Central Highlands yielded much less (Fig. 3c). There were 1,047 records for sorghum and 968 for barley (Fig. 4).

Labor and harvest

This table provides data on agricultural activities and field operations involving machinery, manual labor, and animal traction, including scheduling and duration. Data points cover unique identifiers for each task, type of tillage (conventional, minimal, or zero tillage), and activities such as planting and fertilization. Power source (animal traction vs motorized equipment) is given, along with the type of animals or machinery, costs, time requirements, and implement usage. Manual labor data include the number of workers, daily wages, total days worked, and work hours per day. Additionally, the table documents how crop residues are managed after harvest.

Agricultural inputs

This table covers the application and management of inputs (fertilizer, pesticides, and seed). There are unique identifiers for application dates and types, including fertilization and pest control. Details include whether seed was treated, tool use for dosage adjustments, and the timing of applications. Pest and weed management data include target species, the reasons for applications, and detection methods. Biodiversity usage and practices such as deploying beneficial insects are documented. Product details include type, active ingredients, and nutritional composition. Comprehensive records cover application amounts and units of measurement, enabling precise cost management and input use tracking.

Irrigation

The irrigation table records the type and basic characteristics of the irrigation system, documents water sources and registers the duration and frequency of irrigation, with start and end dates. Metrics on water use include total water consumption per application, average watering time per hectare, volume of water applied, and irrigation per event. Labor data includes the number of workers, daily wages, and total working days.

Costs and revenues

Costs are organized into activity groups, including land preparation, planting, soil analysis, cultural practices, input applications, irrigation, manual and mechanical harvesting, and marketing, as well as indirect expenses. For example, the total costs of sowing and seed include the unit cost of seed multiplied by the amount used, transportation, and labor. Mechanical soil preparation costs comprise labor and unit costs per activity. Soil and water analysis costs are determined by laboratory fees for the properties analyzed. Field work and physical weed control costs encompass labor, transportation, and activities such as weeding and hilling. Input application costs are calculated as product cost x amount applied, along with transportation and labor. Irrigation costs include the cost per event of water, fuel or electricity for pumps, and labor. Harvesting costs, whether manual or mechanical, include labor or activity-specific expenses. Indirect expenses cover activities such as maintenance costs, land leasing, and agricultural insurance.

Revenue is calculated for two main scenarios: direct product sales or self-consumption, with the latter valued at average regional prices. Income is assessed as product amount x unit price.

Technical Validation

As already mentioned, in addition to the quality assurance practices described in Methods, neither farmers nor extension agents recording data received any subsidy associated with the use of a particular technology was not tied to subsidies for farmers or the extension agents collecting the data. Where extension agents were paid for collecting data, payment did not depend on the reported results, in contrast to past subsidy schemes in Mexico, under which agents were paid for reporting yield increases resulting from use of a promoted agricultural practice.

To test whether the reported yield data coincided with the yield data reported by the Mexican agricultural statistics agency SIAP5, a correlation analysis was conducted between the average yield reported from that source at the municipal level and our dataset (Figs. 5–7). The regression lines and correlation coefficients show that the data are within the correct range, although the yields reported in our database tend to be higher, which is to be expected when farmers receive technical assistance.

Usage Notes

The Spanish dataset is the original dataset and we included the English translation of column headers and options in selected menus only to facilitate data usage. We have not translated pest or disease names, since those tend to depend on local vocabulary. We also have not translated answers to open questions (or what people answer after choosing ‘other’ from a drop-down menu). In both these categories, we chose to share the data as is, in Spanish.

Each logbook serves as the main unit of documentation, with the BEM or e-Agrology system generating a unique, unrepeatable identifier for each. All files can be linked through three primary identifiers: Farmer ID, Plot ID, and Logbook ID.

The differences in the numbers of rows among files 2–5 reflect the nature of the activities recorded, which do not correspond on a one-to-one basis. For example, similar activities might have been performed multiple times within a single production period in the same plot, with variations in execution methods, inputs used, and their quantities across different areas. Additionally, multiple crops or products may have been harvested from the same plot, contributing to these differences.

Downloading the dataset from the public link requires user registration and acceptance of the Data Usage Agreement.

Data availability

The dataset is publicly available at the CIMMYT Dataverse repository: https://hdl.handle.net/11529/1054898619. It is organized as a flat folder structure containing six main Excel files (also downloadable in CSV format) and one glossary file. File names are self-descriptive and correspond to the following:

1. Farmer_Plot_Logbook_2012–2022_03.xlsx – Farmer and plot characteristics, including identifiers (Farmer ID, Plot ID, Logbook ID), socio-demographic variables (e.g., education, gender, ethnic group), and management information (technification level, water regime, innovation vs control plots).

2. Sowing_Harvest_Yields_2012–2022_02.xlsx – Sowing and harvest records with variables such as Crop Sowing ID, Yield ID, sowing density, arrangement, crop variety, harvest start/end dates, and yield per hectare.

3. Labor_Harvest_Activities_2012–2022_02.xlsx – Field operations data, including activity identifiers, tillage type, power source (animal traction vs machinery), tools, daily wages, work hours, and fuel consumption.

4. Agricultural_Supplies_2012–2022_01.xlsx – Input application records covering fertilizers, pest control, and seed treatments. Variables include product names, active ingredients, nutrient content, application date, dosage, and rationale for use.

5. Irrigation_2012–2022_01.xlsx – Irrigation system details and practices, including irrigation method (surface, sprinkler, drip), water consumption per event, frequency, duration, labor involved, and volume of water applied.

6. Costs_and_Revenues_2012–2022_02.xlsx – Production costs and revenues, grouped into activity categories (land preparation, sowing, irrigation, harvesting, marketing). Variables include cost per activity, indirect expenses, and revenues (direct sales vs self-consumption).

7. Spanish-English_Glossary.xlsx – Provides translations of technical agricultural terminology used in the dataset to ensure clarity for non-Spanish speakers.

All files share common identifiers (Farmer ID, Plot ID, Logbook ID) to enable linkage. Variable names are explicit; however, certain codes (e.g., Crop Sowing ID, Yield ID, Logbook ID) and derived measurements (e.g., plot surface from satellite imagery, technification level) are clarified in the metadata and glossary.

Code availability

Data preparation and quality check were conducted using R (R version 4.3.2, released on October 31, 2023) on a Windows 11 × 64 (build 26100) system, running on the x86_64-w64-mingw32/x64 (64-bit) platform. The publicly available Github repository (https://github.com/gmonpr/Historical-Agronomic-Dataset) contains an example of the code used for data standardization and translation. For easier data use, the repository also includes example code for merging data tables from the Historical Agronomic Dataset (2012–2022).

References

Ibarrola-Rivas, M. J., Castillo, G. & González, J. Social, economic and production aspects of maize systems in Mexico. Investigaciones Geográficas, (102). https://doi.org/10.14350/rig.60009 (2020).

World Bank. Mexico Systematic Country Diagnostic https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/588351544812277321/pdf/Mexico-Systematic-Country-Diagnostic.pdf (World Bank, 2019).

Hernandez-Ochoa, I. M. et al. Climate change impact on Mexico wheat production. Agric. For. Meteorol. 263, 373–387 (2018).

Estrada, F., Tol, R. S. J., Gay-García, C. & Conde, C. Impacts and economic costs of climate change on Mexican agriculture. Reg. Environ. Change 22, 123, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-022-01986-0 (2022).

SIAP (Agricultural and Fisheries Information Service). Annual Agricultural Crop Reports. Mexican Government. Available at: https://nube.agricultura.gob.mx/cierre_agricola (Official crop yield statistics, 1980s–present.) (accessed 2025).

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). FAOSTAT: Mexico Crop Production Data. Available at: http://www.fao.org/faostat/ (1961–present).

NASA SEDAC (Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center). Twentieth Century Crop Statistics for the Americas. Columbia University. Available at: https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/ (1900–2017).

Sánchez-Gómez, J. et al. Spatial and temporal variability of maize yields in central Mexico: A yield gap analysis. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 10(2), 345–358, https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v10i2.1678 (2019).

Hernández-Ruiz, J. et al. Agronomic management and its impact on sustainability in maize systems of the Bajío region. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 11(5), 1123–1136, https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v11i5.2381 (2020).

Turrent-Fernández, A. et al. Drivers of maize productivity in smallholder systems of Mexico: A panel data analysis. Agric. Soc. Desarro. 14(2), 231–256 (2017).

Aguilar-Rivera, N. et al. Sustainable intensification of maize-wheat systems in Mexico: A meta-analysis of yield gaps and farmer practices. Agric. Syst. 185, 102943, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102943 (2020).

Barrera-Rodríguez, A. I. et al. Labor and input-use efficiency in smallholder maize farms: Evidence from Central Mexico. J. Agric. Sci. 158(3), 189–202, https://doi.org/10.1017/S002185962000038X (2020).

INEGI (National Institute of Statistics and Geography). National Agricultural Survey (ENA). Available at: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ena/ (Longitudinal farm-level survey.) (2007–present).

Gardeazabal, A. et al. Knowledge management for innovation in agri-food systems: a conceptual framework. Knowl. Manage. Res. Pract. 21, 303–315, https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2021.1884010 (2023).

Liedtka, J., Salzman, R. & Azer, D. Design Thinking for the Greater Good: Innovation in the Social Sector (Columbia Univ. Press, 2017).

Waggoner, B. Silverlight. In Compression for Great Video and Audio (ed. Waggoner, B.) 473–496 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-240-81213-7.00026-5 (Focal Press, 2010).

Tabarés, R. HTML5 and the evolution of HTML: tracing the origins of digital platforms. Technol. Soc. 65, 101529 (2021).

CIMMYT. Yield and Yield Components: A Practical Guide for Comparing Crop Management Practices (CIMMYT, 2015).

Gardeazábal-Monsalve, A., de Ramirez Ortega, M. L., Pacheco Rodríguez, G. M. & Garza Sánchez, E. Historical Agronomic Dataset - Insights from Mexico (2012–2022) (Version 4). CIMMYT Research Data & Software Repository Network https://hdl.handle.net/11529/10548986 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contribution of 4,927 people who collected and captured data from fields across Mexico and that of 357 people who curated data in near real time. We also thank all CIMMYT staff and collaborators in the hubs who contributed to the network for sustainable agriculture that enabled the data collection. The work to create this dataset was supported by a portfolio of projects that supported CIMMYT’s work on sustainable agriculture and digital innovation in Mexico between 2011 and 2024, listing here only the main ones: MasAgro Productor, PROAGRO Productivo, Cultivos para Mexico (supported by the Mexican Ministry of Agriculture SADER, previously SAGARPA), MasAgro Guanajuato (supported by the state government of Guanajuato through SDAyR), Strengthening market access for smallholder maize and legume farmers in Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Campeche (supported by Walmart Foundation), Milpa Sustentable en la Península de Yucatan (supported by Fundacion Haciendas del Mundo Maya and Fomento CitiBanamex), various responsible sourcing and sustainability projects with the private sector (supported by Bimbo, Heineken, Ingredion, Kellanova (Kellogg), Nestle and Pepsico & Trimex), the OneCGIAR initiatives Excellence in Agronomy and Digital Innovation (supported by CGIAR W1&W2 donors including the Bill and Melida Gates Foundation, grant number: INV-005431), and Regenerative Agriculture Data (RAD): Evidence base of MasAgro’s farmer innovations (supported by the Rockefeller Foundation). Finally, we thank the team members who have contributed significantly to data cleaning over the years, including Enrique Garza Sanchez, Cristhian Ramos Duana, and Patricia Moreno Garcia, as well as those who contributed to the design and development of the data collection system, David Garcia Gonzalez. We thank Mike Listman for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Andrea Gardeazabal: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Writing – Original Draft Preparation. Jose Alberto Cabello Cortes: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing. Simon Fonteyne: Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation. Benancio Jimenez Gomez: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing. Abel Jaime Leal Gonzalez: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing. Daniel Núñez Jiménez: Software, Writing – Review & Editing. Sylvanus Odjo: Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing. Guadalupe Monserrat Pacheco Rodriguez: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing – Review & Editing. Maria de Lourdes Ramirez Ortega: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing – Review & Editing. Jelle Van Loon: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing. Luis Vargas Rojas: Software, Writing – Original Draft Preparation. Nele Verhulst: Methodology, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation. Bram Govaerts: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gardeazábal-Monsalve, A., Cabello Cortés, J.A., Fonteyne, S. et al. A decade of on-farm data about improved cereal and legume cropping in Mexico. Sci Data 12, 1873 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06143-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06143-w