Abstract

Invasive alien species (IAS) are a direct driver of global biodiversity loss, and can also affect societies, economies and human health. Maintaining up-to-date alien species inventories is important for informing policy and management decisions. Here we present the Cyprus Database of Alien Species (CyDAS), an openly accessible, online dataset providing informational resources on alien species on the island of Cyprus. The dataset (up to end of December 2023) includes information on 1,293 terrestrial, freshwater and marine introduced taxa, with species profiles being constantly updated to keep track of new arrivals. The CyDAS aims to catalogue and supplement our knowledge on the alien species of Cyprus; to help develop and enhance early warning and rapid response systems; to raise public awareness of the risks posed by the IAS subset; to strengthen and enhance engagement and public participation in surveys in the field of biological invasions; and to inform IAS policy. CyDAS is a free, online database and we would like to encourage other researchers and decision-makers to provide information on IAS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Invasive alien species (IAS) affect native biodiversity and ecosystem as one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss1,2,3. In addition, they can inflict serious socioeconomic impacts affecting inter alia agriculture, forestry and fisheries4,5, the livelihoods of people6 as well as human-, animal- and plant-health7,8,9,10,11,12. Over the past few centuries, the number of alien species across the globe has been increasing, showing no signs of saturation, due to the ever-increasing transportation of people and goods13,14,15. This worldwide phenomenon demonstrates the need for up-to-date alien species inventories, pooling information and resources on alien species on the local, national and regional scales to aid mitigation of their spread and impacts16,17,18,19,20,21.

Cyprus is an island within the Mediterranean Sea situated at the crossroads of three continents (Europe, Africa and Asia). The movement of people and goods from various regions since ancient times has gradually shaped the landscape of Cyprus22,23,24,25,26,27. To this day, the continuous import of goods and movement of people, provide more and more opportunities for alien species to arrive in Cyprus, through the increased accessibility from new, distant regions28. Earliest records of human settlements date back to 10,500–9000 BC, with early settlers introducing to the island livestock (e.g. cattle, sheep and other domesticated animals), deer, foxes, and mice as well as cultivated plants from neighbouring regions22,23. Due to its strategic position, throughout its history, the island has been under the control of a series of empires (Holy Roman, Byzantine, Venetian, Ottoman, and British) and suffering invasions by neighbouring pirate tribes.

Here we provide an overview of the CyDAS, the first island-wide dataset on alien species currently containing data on a total of 1,293 taxa reported from Cyprus. The CyDAS provides standardised taxonomic, ecological, spatial and temporal data on alien species detected on Cyprus as well as data on their introduction pathways, establishment status, impacts, available scientific literature and information sources. This dataset aims to (1) catalogue and supplement data on the taxonomy, distribution, habitats, origin, establishment status, impacts and scientific literature on alien species, (2) provide information on alien species introduced to the island, IAS yet to be detected to help develop early warning and rapid response systems as well as biosecurity advice to mitigate their spread and impacts, (3) raise public awareness of the risks posed by IAS, strengthen and enhance public participation in the scientific research of biological invasions, and (4) inform IAS policy through the provision of up-to-date information and resources on IAS. This dataset aims to assist national efforts to confront biological invasions and IAS according to national and international legislative acts, such as the EU IAS Regulation, EU Biodiversity Strategy, EU Nature Restoration Plan and the Global Biodiversity Framework.

Methods

Data collection

Through a COST Action COST | European Cooperation in Science and Technology, Alien Challenge (COST TD1209) (2014–2018), Drs Angeliki Martinou and Argyro Zenetos began the compilation of an offline database on the IAS of the island of Cyprus, named the Cyprus Invasive Alien Species (CY.I.A.S) inventory. Data were pooled from both published and unpublished material, including online databases and projects such as Delivering Alien Invasive Species Inventories for Europe (DAISIE)29, the European Alien Species Information Network (EASIN)30, and the Ellenic Network on Aquatic Invasive Species (ELNAIS)31. The resulting spreadsheet also contained unstandardized information on the introduction pathways, origin, establishment success, first detection/collection date, and first reports of the species, depending on the availability of data at the time32. In 2020 the CY.I.A.S inventory was published as a checklist through the Global Register of Introduced and Invasive Species (GRIIS)33, an online database providing validated and verified national checklists of introduced (alien) and IAS at the country, territory, and associated island level, on a global scale. The CY.I.A.S was later supplemented and renamed as the Cyprus Database of Alien Species (CyDAS)33 through the Researching the Invasive Species of Kýpros (RIS-Ký) project (DPLUS056) and subsequent Darwin Plus projects (DPLUS088, 124), funded by the UK government between 2017 and 2023. As well as compiling much new data, the RIS-Ký project standardised the CY.I.A.S spreadsheet into a harmonised and strictly codified set of fields (see Table 1 and Methods below), developed access to online APIs of Catalogue of Life34 and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)35 for taxonomic harmonisation and up-to-date distributional information access, and developed a web GUI for data management, publishing, and public access.

From 2021 to 2023 this database was further supplemented with data on taxa, their distribution, habitats, impacts, literature and online resources, since up-to-date databases and species accounts for alien species and IAS are pivotal for monitoring biological invasions, species’ distribution and impact, and ultimately guiding decision making36,37,38,39. Data on alien species were pooled from published scientific literature reviews19,24,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48 as well as through searches on Google Scholar using as search strings the “latin species name” and “Cyprus”. Taxonomic experts were also consulted both in person and via emails from 2017 to 2024. Nomenclature changes and backdating data on marine organisms published in 2024 referring to species reported by 2023 were included48. Finally, online resources such as the Flora of Cyprus website49, EASIN30, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)35, and the Terrestrial Arthropods of Cyprus database50 were checked. Data collection for this report was terminated on 31st December 2023.

Structure of dataset

The dataset is provided as a comma delimited file (.csv). For each species profile on the database, species data on taxonomy, common names, distribution, habitat, first detection year, introduction pathways, establishment status, impacts and references, are provided for the island of Cyprus (Table 1). Species classification and taxonomy followed the CoL and the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS)51. Additionally, species’ taxonomy was also checked and corrected based on recent re-classifications for Chalcidoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera)52, families Curculionidae and Dermestidae (Insecta: Coleoptera). As this dataset covers the island of Cyprus as a whole, where available, common names for each taxon are provided in Greek, English and Turkish. Habitats occupied by alien species follow the EUNIS Habitat Classification Scheme, while introduction pathways follow the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) classification and follow-up modifications53,54 Data on introduction pathways for a large number of species was taken verbatim from EASIN30, where data for primary and secondary pathways are given at the EU-level. Nevertheless, these introduction pathways were not uncritically copied, with cases of unaided introductions (spread through borders) omitted for a number of species where it was considered that they have low dispersal abilities. Additionally, cases where introduction pathways have been copied from EASIN30 are denoted both on the CyDAS website as well as the provided database. Where available the year of first detection for each species is provided as a numerical value, whereas if data is available on a year range or century data are presented under “Pathway detail”.). The status of taxa (herein under the “Establishment status detail” column) was assessed as alien or “truly alien”, cryptogenic (taxa of unknown origin, neither demonstrably native nor introduced55 at the global level) or of questionable status. The latter category is rather ambiguous, according to EASIN, concerning species records with insufficient information or with uncertain identification at the EU scale30. We used this category for taxa mentioned in EASIN as of “questionable status”, but also for taxa with unresolved taxonomic status (also known as data deficient), not mentioned as cryptogenic in EASIN. Classification was based on local expert knowledge of the species’ status on the island as well as scientific literature21,44,49 (Table 1).

Summary of the inventory

As of the 31st December 2023, the CyDAS includes a total of 1,293 taxa distributed within 26 phyla, 151 orders and 420 families. The vast majority, that is a total of 1,101 species (85.1%) are truly alien to the island, while 143 (11.1%) are cryptogenic and 49 (3.8%) of questionable status (Table 2).

Almost half (48%) of the “truly” alien species on the island are reported as established. While 38% of the alien species are not established (38.0%), the establishment status of 12% of the species is unknown (Table 2) (Table 1: see Establishment status detail). Regarding cryptogenic species, most are either established (46.9%) or of unknown establishment status (41.9%).

When excluding species that have been proved to be absent, exterminated or extinct, the number of established, indoors introduced, not established and alien species of unknown establishment status falls to 1,283 (Fig. 1).

The species included in the database occupy a wide range of habitats (Figs. 2 and 3). For the three most species rich phyla (i.e. Tracheophyta, Arthropoda and Chordata), it is evident that most alien vertebrates recorded from Cyprus are marine organisms (i.e. fishes), while vascular plants are mostly found in agricultural land and other anthropogenic sites such as gardens, mixed landscapes (e.g. roadsides), parks but also in more natural areas near running waters i.e. streams and rivers (Fig. 3). Insects seem to follow predominantly their host plants in urban settings44,56,57,58.

The main introduction pathways of alien species are shown to be a) escape from confinement due to agricultural, horticultural or ornamental practices, b) transportations as contaminants on nursery material or plants; as well as c) the unaided introduction of alien species (Figs. 4, 5). Trends regarding alien vascular plants, arthropods and vertebrates (Fig. 6) reflect studies at the European scale59,60,61.

Introduction pathway subcategories of alien species to the island of Cyprus based on the CBD pathway classification scheme. Where data at the island level were not found, introduction pathways were taken from EASIN (https://easin.jrc.ec.europa.eu/easin).

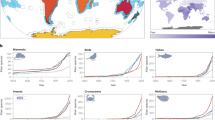

The year 1800 AD was chosen as a cut-off year to illustrate trends in the detection and/or publication and accumulation of alien species (Figs. 7, 8) due to the absence of precise chronological data on alien species prior to the 1800s. The cumulative number of alien species has been exponentially climbing since the 1860s (Fig. 7b), while the number of unintentional introductions per annum shows a steep increase after the 1950s (Fig. 7a). Colonialism has been shown to influence species’ introductions across the world62, and is relevant to Cyprus. The first spike on the graph (Fig. 7a) appears at the era of the “Anglocracy” (British Empire: 1878–1959) during which time economically important flora were introduced to the island27,63,64,65. The detection of alien marine organisms in Cyprus dates back to 189966, however, the 1870s probably initiated the introduction history of marine aliens through the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Following independence of the island in 1960 the number of alien species has continued to increase (Fig. 7), probably through international commerce intensification, continuous development and urbanisation, as well as increased detection of alien species due to the growing interest in the field of biological invasions in recent times.

Number of alien species reported each year in Cyprus for species introduced intentionally (i.e. introduction pathway = release in nature) (blue line) and unintentionally (red line) (95% confidence intervals in light red and blue) (a). Cumulative number of alien species recorded in Cyprus each year (b).

It is evident that the escape of alien species from confinement has steadily increased since 1800 (Fig. 8). Species introduced through interconnected waterways (corridors) and transported as stowaways or contaminants steeply increase, especially after the 1960s. While, the number of species released in nature seems to be relatively steady. Although low, the number of species that have reached Cyprus unaided, has been increasing after the 2000s probably due to increasing dispersal of alien marine species in the Mediterranean Basin from the Suez Canal.

Information on the establishment status and broad habitat categories is known for a high percentage of species (Fig. 9). Data on first year of detection are available for 63.1% of species (Fig. 9), while data on invasiveness on an island-wide level are scarce (20%) (Fig. 9). Thus, further research on the impacts of alien species on Cyprus is necessary following assessment protocols such as the Environmental Impact Classification for Alien Taxa (EICAT) and Socioeconomic Impact Classification for Alien Taxa (SEICAT)67,68,69,70,71 as well as investigations on any of their beneficial roles such as in the case of biocontrol agents44.

Data Records

The analysed dataset, code, and supplementary files are publicly available in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17023319), with version v5 representing the peer-reviewed version associated with this article72. A short description of all files can be found in READ ME.docx. The dataset consists of CYDAS_template.docx, .html and .Rmd including the custom code used to analyse the data. The raw data downloaded from the CyDAS database (https://ris-ky.info/cydas) can be found in the file CYDAS-raw-data.csv. This.csv file includes the following columns for each taxon, explained in detail in Table 1: Scientific name, Author, Family, Order, Phylum, Catalogue of Life ID, GBIF TaxonKey, Common name (English), Common name (Greek), Common name (Turkish), Online resource, Global distribution, Terrestrial habitat, Marine habitat, Habitat detail, First record, First record (range end date), Pathway, Pathway detail, Establishment status, Establishment status detail, Impacts, Impact detail, References, Other notes, Last edited, Link. As for some taxa information was compiled utilising more than one references, a separate file “Species_references_file.xlsx” is also provided, listing all available literature for each taxon included in the dataset including columns: Scientific name; Author; Family; Order; Phylum; CyDAS link; References; DOI/Link (where available). Due to taxonomic discrepancies between the GBIF backbone taxonomy and current up-to-date species classifications, changes applied to the raw dataset are explained in Taxonomic changes applied to raw dataset.csv, including columns: Species, Author, Family, Order, Phylum, NEW_Family, NEW_Order, NEW_Phylum. The produced dataset is named “Clean_dataset_up_to_31_Dec_2023.csv”, following the structure of “CYDAS-raw-data.csv”. Regarding classification for the columns “Terrestrial Habitat” and “Pathway”, categories and subcategories can be found in the files, “Habitat_classification_scheme_categories_and_subcategories_EUNIS.csv” and “Introduction_pathways_categories_and_subcategories.csv”, respectively.

Technical Validation

Record verification

Records of alien species were gathered, assessed and added to the database from published scientific literature reviews19,24,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48 and searches on Google Scholar using as search strings the “latin species name” and “Cyprus”, by the authors. Taxonomy was based on COL (and linked to GBIF) for uniformity and standardization of methods and classification schemes, despite some taxonomic inaccuracies regarding some synonymies and placement of taxa as corrected for species in the families Curculionidae, Dermestidae, Ptinidae and the superfamily Chalcidoidea. Where no further information was available on the presence of a previously recorded species or the first year of introduction, its establishment status and first detection year were assessed as unknown or left blank, respectively. Marine species inventories heavily relied on the work of Dr Argyro Zenetos and Dr Nikolas Michaelidis (unpublished data), while plants were assessed by Mr Jakovos Demetriou, Jodey Peyton, Dr Oliver Pescott and Owen Mountford, following scientific literature, online resources, and field surveys24,49,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80. Freshwater species were assessed by Dr Maria Stoumboudi, Mr Jakovos Demetriou, Dr Angeliki Martinou and Dr Argyro Zenetos. Arthropoda were largely based on findings of DPLUS12444, assessed by Mr Jakovos Demetriou and Dr Angeliki Martinou.

Usage Notes

In addition to the dataset at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15847604)72, the CyDAS is also available, including species profiles for all 1,293 taxa (https://ris-ky.info/cydas). The CyDAS aims to accumulate scientific knowledge around the alien species of Cyprus in order to ensure better data usage and interoperability. By providing relevant sources and helping locate scientific literature, both the dataset and its interface can enhance the advancement of research based on identified knowledge gaps. The CyDAS can guide literature investigations on alien species found in Cyprus and further assist scientific research by indicating relevant sources. Resources provided by the CyDAS are openly available and constantly updated. Data can be used for risk assessments and the prioritisation of conservation practices in order to safeguard native biodiversity and habitats. Data provided on all alien species can be also utilised by government officials to report on alien species at the national scale, in order to track progress towards biodiversity targets and EU legislation. Such targets have been set from initiatives such as the Global Biodiversity Framework Target 6 to “Reduce the Introduction of Invasive Alien Species by 50% and Minimize Their Impact”, as well as the EU Biodiversity Strategy and EU Nature Restoration Plan aiming to “manage established invasive alien species and decrease the number of Red List species they threaten by 50%”, by 2030. Furthermore, the undertaken incorporation of data on species yet to have become established in the wild (i.e. ornamental plants common in gardens and parks as monitored in the UK81), enables CyDAS to help monitor cultivated species that may in the future become invasive (such as garden escapees) or previously exterminated taxa that have been recently detected again such as Aedes aegypti Linnaeus, 176282,83. Lastly, keeping an up-to-date inventory of alien species on the island can help us keep track and extrapolate trends of their invasion history and their rate of accumulation.

Limitations

Despite our rigorous literature and material surveys the inventory of alien species of Cyprus may be incomplete or subject to changes due to some of the following gaps and limitations84:

-

Lack of experts for most taxonomic and organismic groups particularly evident in organisms such as alien pathogens, for which only one source was located43. This illustrates one of the side-effects of the globally observed taxonomic impediment (i.e. the world-wide shortage of important taxonomic information and the shortage of trained taxonomists) hampering identification, monitoring and ultimately management efforts of alien and IAS.

-

Inconsistencies in taxonomic placement and classification of species in linked databases i.e. GBIF and CoL (as observed for example for species in the beetle families Dermestidae, Chrysomelidae and Curculionidae as well as synonyms for selected taxa).

-

Lack of documented habitat data for alien species in their introduced range and inconsistencies in classification schemes used between databases49.

-

Knowledge gaps regarding how species were introduced to the island (as such data made available from the EASIN were utilized annotating such cases in the database). For marine species the uncertainty in the introduction pathway, as shown for Mediterranean marine species, has led to reporting two pathways (Corridor and Natural dispersal across borders) for all Lessepsian species85.

-

Inconsistencies in literature and a consensus on the alien or native status of selected species regarded as cryptogenic, of questionable status or truly alien with insufficient documentation (such as the carpenter bee Xylocopa pubescens, a species of questionable status44).

-

Lack of impact studies and assessments of the invasiveness of alien species based on their potential or observed impact on biodiversity, human health, and socioeconomic parameters.

-

Lack of robust standardized methodologies and monitoring protocols.

-

Lack of an island-wide, centralized biological record centre and an infrastructure to host and support biodiversity data, including alien and IAS (for example a national node on the GBIF or an up-to-date database on the island’s biodiversity).

-

The sensitive geopolitical situation on the island setting boundaries and restrictions in collaborations, monitoring, and EU IAS policy at the island level.

Thus, we encourage the competent authorities, scientific experts and local researchers to contribute to the dataset with more data on the species where omissions or inconsistencies are identified. As new information is constantly added, the data presented here is likely to be modified and updated. For example, a total of 126 alien marine species were reported up to July 200940, while by December 2017 this number rose to 160 species19. The most recent account reports 178 truly alien species introduced by December 202021. Herein, we report 254 marine alien, cryptogenic and species of questionable status detected by December 2023.

Up-to-date csv files are made available in Zenodo72 where annual updates will be uploaded (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15847604)72 or can be obtained throughout communication with the article’s authors. National checklists available through GRIIS on GBIF will be also updated30. Further research on both the beneficial and adverse effects of alien species is necessary to enable researchers, conservationists and decision makers to understand which of the alien species on the island are invasive. This is particularly important considering both the global biodiversity loss caused by IAS and the presence of numerous notorious IAS of Union concern on the island such as the common myna Acridotheres tristis Linnaeus, 1766, the red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii Girard, 1852, the striped eel catfish Plotosus lineatus (Thunberg, 1787), the pond slider Trachemys scripta Schoepff, 1792, the golden wreath wattle Acacia saligna (Labill.) H.L.Wendl., the tree of heaven Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle, and the little fire ant Wasmannia auropunctata (Roger, 1863), many of which are already established on Cyprus45,86,87,88,89,90,91. Nevertheless, with further research, prioritization of management needs and communication with local experts such data can be integrated into the database.

Data availability

All data are openly available in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17023319), with version v5 representing the peer-reviewed version associated with this article72.

Code availability

No custom computer code or algorithms were used to process or generate the data presented in this manuscript. The code used in RStudio for the provided graphs is given in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17023319).

References

Díaz, S. et al. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579 (IPBES secretariat, 2019).

Roy, H. E. et al. Summary for Policymakers of the Thematic Assessment Report on Invasive Alien Species and their Control of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7430692 (IPBES secretariat, 2023).

Roy, H. E. et al. Curbing the major and growing threats from invasive alien species is urgent and achievable. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1216–1223, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02412-w (2024).

Paini, D. R. et al. Global threat to agriculture from invasive species. PNAS 113(27), 7575–7579, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602205113 (2016).

Haubrock, P. J. et al. Economic costs of invasive alien species across Europe. In: Zenni, R.D., McDermott, S., García Berthou, E., Essl, F. (Eds) The economic costs of biological invasions around the world. NeoBiota 67, 153-190, https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.67.58196 (2021).

Perrings, C. The socioeconomic links between invasive alien species and poverty (Report of the Global Invasive Species Program, 2005).

Schrader, G., Unger, J. G. & Starfinger, U. Invasive alien plants in plant health: a review of the past ten years. EPPO Bulletin 40(2), 239–247, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2338.2010.02379.x (2010).

Vilcinskas, A. Pathogens as biological weapons of invasive species. PLoS Pathog. 11(4), e1004714, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004714 (2015).

Mazza, G. & Tricarico, E. Invasive Species and Human Health https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786390981.0000 (CABI, Wallingford, 2018).

Jones, B. A. & McDermott, S. M. Health impacts of invasive species through an altered natural environment: assessing air pollution sinks as a causal pathway. Environ. Resource Econ. 71, 23–43, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-017-0135-6 (2018).

Starfinger, U. & Schrader, G. Invasive alien plants in plant health revisited: another 10 years. EPPO Bulletin 51(3), 632–638, https://doi.org/10.1111/epp.12787 (2021).

Tsirintanis, K. et al. Bioinvasion impacts on biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human health in the Mediterranean Sea. Aquat. Invasions 17(3), 308–352, https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2022.17.3.01 (2022).

Hulme, P. E. Trade, transport and trouble: Managing invasive species pathways in an era of globalization. J. Appl. Ecol. 46(1), 10–18, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01600.x (2009).

Seebens, H. et al. No saturation in the accumulation of alien species worldwide. Nat. Commun. 8(1), 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14435 (2017).

Seebens, H. Invasion Ecology: Expanding trade and the dispersal of alien species. Curr. Biol. 29(4), 120–122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.12.047 (2019).

Kenis, M., Rabitsch, W., Auger-Rozenberg, M. A. & Roques, A. How can alien species inventories and interception data help us prevent insect invasions? Bull. Entom. Res. 97, 489–502, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485307005184 (2007).

Roy, H. E. et al. GB non-native species information portal: documenting the arrival of non-native species in Britain. Biol. Invasions 16, 2495–2505, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-014-0687-0 (2014).

Lucy, F. E. et al. INVASIVESNET towards an international association for open knowledge on invasive alien species. Manag. Biol. Invasions 7(2), 131–139, https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2016.7.2.01 (2016).

Tsiamis, K. et al. Marine Strategy Framework Directive - Descriptor 2, Non-Indigenous Species, Delivering solid recommendations for setting threshold values for non-indigenous species pressure on European seas https://doi.org/10.2760/035071 (Publications Office of the European Union, 2021).

Arianoutsou, M. et al. HELLAS-ALIENS. The invasive alien species of Greece: time trends, origin and pathways. NeoBiota 86, 45–79, https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.86.101778 (2023).

Galanidi, M. et al. Validated inventories of non-indigenous species (NIS) for the Mediterranean sea as tools for regional policy and patterns of NIS spread. Diversity 15, 962, https://doi.org/10.3390/d15090962 (2023).

Zeder, M. A. Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact. PNAS 105(33), 11597–11604, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0801317105 (2008).

Vigne, J. D. et al. The transportation of mammals to Cyprus sheds light on early voyaging and boats in the Mediterranean sea. Eurasian Prehistory 10(1-2), 157–176 (2014).

Georgiades, C. The adventive flora of Cyprus, taxonomic, floristic, phytogeographic, ecophysiological study (Ph.D. Thesis, Athens University, 1995).

Ciesla, W. M. Forests and forest protection in Cyprus. For. Chron. 80, 107–113, https://doi.org/10.5558/tfc80107-1 (2004).

Chatzikyriakou, G. N. History of the Forests of Cyprus: From ancient times until the end ofthe Ottoman Empire, Volume 1.(Cyprus Forest Association, 2017).

Pescott, O. L. et al. The Forest onthe Peninsula: Impacts, Uses and Perceptions of a Colonial Legacy in Cyprus. In: Queiroz, A., Pooley, S. (Eds) Histories of Bioinvasions in the Mediterranean, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74986-0_9 (Environmental History 8, Springer, 2018).

Seebens, H. et al. Global rise in emerging alien species results from increased accessibility of new source pools. PNAS 115(10), 2264–2273, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1719429115 (2018).

Roy, D. et al. DAISIE - Inventory of alien invasive species in Europe. Version 1.7. Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO). Checklist dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/ybwd3x accessed via GBIF.org on 2024-06-18 (2020).

EASIN. European Alien Species Information Network https://easin.jrc.ec.europa.eu/easin (2024).

Zenetos, A. et al. ELNAIS: A collaborative network on Aquatic Alien Species in Hellas (Greece). Manag. Biol. Invas. 6(2), 185–196, https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2015.6.2.09 (2015).

Martinou, A. F. Creating CY. I.A.S: The Cyprus Invasive Alien Species (CY.I.A.S) inventory. Report – CYIAS. STSM TD 1209. Short term Scientific Mission Report https://ris-ky.info/sites/default/files/STSM%20REPORT%20%20AF%20Martinou.pdf (2014).

Martinou, A. et al. Global Register of Introduced and Invasive Species - Cyprus. Version 1.9. Invasive Species Specialist Group ISSG. Checklist dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/uryl57 (2020).

Catalogue of Life. https://www.catalogueoflife.org/ (2024).

GBIF. Global Biodiversity Information Facility https://www.gbif.org/ (2024).

Katsanevakis, S. et al. Building the European Alien Species Information Network (EASIN): a novel approach for the exploration of distributed alien species data. BioInvasions Rec 1(4), 235–245, https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2012.1.4.01 (2012).

Tsiamis, K. et al. The EASIN Editorial Board: Quality assurance, exchange and sharing of alien species information in Europe. Manag. Biol. Invasions 7, 321–328, https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2016.7.4.02 (2016).

Deriu, I., D’Amico, F., Tsiamis, K., Gervasini, E. & Cardoso, A. C. Handling big data of alien species in Europe: The European alien species information network geodatabase. Front. ICT 4, 20, https://doi.org/10.3389/fict.2017.00020 (2017).

Zenetos, A. & Galanidi, M. Mediterranean non indigenous species at the start of the 2020s: recent changes. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 13, 10, https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-020-00191-4 (2020).

Katsanevakis, S., Tsiamis, K., Ioannou, G., Michailidis, N. & Zenetos, A. Inventory of alien marine species of Cyprus (2009). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 10(2), 109–134, https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.113 (2009).

Zenetos, A., Konstantinou, F. & Konstantinou, G. Towards homogenization of the Levantine alien biota: Additions to the alien molluscan fauna along the Cypriot coast. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 2, e156, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755267209990832 (2009).

Gerber, E. & Schaffner, U. Review of Invertebrate Biological Control Agents Introduced Into Europe (CABI Switzerland, 2016).

Magliozzi, C. et al. European primary datasets of alien bacteria and viruses. Sci. Data 9(1), 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01485-1 (2022).

Demetriou, J. et al. The Alien to Cyprus Entomofauna (ACE) database: a review of the current status of alien insects (Arthropoda, Insecta) including an updated species checklist, discussion on impacts and recommendations for informing management. NeoBiota 83, 11–42, https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.83.96823 (2023).

Demetriou, J. et al. Running rampant: the alien ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Cyprus. NeoBiota 88, 17–73, https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.88.106750 (2023).

Zenetos, A. et al. Status and trends in the rate of introduction of marine non-indigenous species in European seas. Diversity 14(12), e1077, https://doi.org/10.3390/d14121077 (2022).

Rousou, M. et al. Polychaetes (Annelida) of Cyprus (Eastern Mediterranean Sea): An updated and annotated Checklist including new distribution records. Diversity 15(8), 941, https://doi.org/10.3390/d15080941 (2023).

Zenetos, A., Delongueville, C. & Scaillet, R. An overlooked group of citizen scientists in non indigenous species (NIS) information: shell collectors and their contribution to molluscan NIS xenodiversity. Diversity 16, 299, https://doi.org/10.3390/d16050299 (2024).

Hand, R., Hadjikyriakou, G. N. & Christodoulou, C. S. Flora of Cyprus – a dynamic checklist http://www.flora-of-cyprus.eu/ (2011–).

CyArthros. Terrestrial Arthropods of Cyprus (https://cyarthros.myspecies.info/ (2024).

WoRMS Editorial Board. World Register of Marine Species https://www.marinespecies.org (2024).

Burks, R. et al. From hell’s heart I stab at thee! A determined approach towards a monophyletic Pteromalidae and reclassification of Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera). J. Hymenopt. Res. 94, 13–88, https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.94.94263 (2022).

Harrower, C., Scalera, R., Pagad, S., Schönrogge, K. & Roy, H. Guidance for Interpretation of the CBD Categories of Pathways for the Introduction of Invasive Alien Species (Publications Office of the European Union, 2018).

Pergl, J. et al. Applying the convention on biological diversity pathway classification to alien species in Europe. NeoBiota 62, 333–363, https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.62.53796 (2020).

Carlton, J. T. Biological invasions and cryptogenic species. Ecology 77, 1653–1655, https://doi.org/10.2307/2265767 (1996).

Lopez-Vaamonde, C., Glavendekić, M. & Paiva, M. R. Invaded habitats. BioRisk 4(1), 45–50, https://doi.org/10.3897/biorisk.4.66 (2010).

Branco, M. et al. Urban trees facilitate the establishment of non-native forest insects. NeoBiota 52, 25–46, https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.52.36358 (2019).

Bonnamour, A., Blake, R. E., Liebhold, A. M. & Bertelsmeier, C. Historical plant introductions predict current insect invasions. PNAS 120(24), e2221826120, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2221826120 (2023).

Arianoutsou, M. et al. Alien plants of Europe: introduction pathways, gateways and time trends. PeerJ 9, e11270, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11270 (2021).

Katsanevakis, S., Zenetos, A., Belchior, C. & Cardoso, A. C. Invading European seas: Assessing pathways of introduction of marine aliens. Ocean & Coast. Manag. 76, 64–74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.02.024 (2013).

Zenetos, A. Progress in Mediterranean bioinvasions two years after the Suez Canal enlargement. Acta Adriat. 58(2), 347–358, https://doi.org/10.32582/aa.58.2.13 (2017).

Lenzner, B. et al. Naturalized alien floras still carry the legacy of European colonialism. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6(11), 1723–1732, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01865-1 (2022).

Baker, S. W. Cyprus As I Saw It In 1879 (Macmillan and Co, 1879).

Wild, A.E. Report On The Forests In The South And West Of The Island Of Cyprus. (Presented to both Houses of Parliament of Her Majesty No 10 (C-2427), Harrison and Sons, 1879).

Harris, S. E. Colonial Forestry and Environmental History: British Policies in Cyprus, 1878-1960 (PhD Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, 2007).

Monterosato, T. Coquilles marines de Chypre. J. Conchol. 47(4), 392–401 (1899).

Hawkins, C. L. et al. Framework and guidelines for implementing the proposed IUCN Environmental Impact Classification for Alien Taxa (EICAT). Divers. Distrib. 21(11), 1360–1363, https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12379 (2015).

Bacher, S. et al. Socio-economic impact classification of alien taxa (SEICAT). Methods Ecol. Evol. 9(1), 159–168, https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12844 (2017).

Galanidi, M., Zenetos, A. & Bascher, S. Assessing the socio-economic impacts of priority marine invasive fishes in the Mediterranean with the newly proposed SEICAT methodology. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 19, 107–123, https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.15940 (2018).

IUCN. IUCN EICAT Categories and Criteria. The Environmental Impact Classification for Alien Taxa First edition (IUCN, Gland, 2020).

Kumschick, S. et al. Appropriate uses of EICAT protocol, data and classifications. NeoBiota 62, 193–212, https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.62.51574 (2020).

Demetriou, J. et al. Cyprus Database of Alien Species – CyDAS. zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17023319 (2025).

Meikle, R. D. Flora of Cyprus, Vol. 1 (1977).

Meikle, R. D. Flora of Cyprus, Vol. 2 (1985).

Tsintides, T., Hadjikyriakou, G. N. & Christodoulou, C. S. Trees and Shrubs in Cyprus (Foundation Anastasios G. Leventis – Cyprus Forest Association, 2002).

Christofides, Y. Illustrated Flora of Cyprus (Yiannis Christofides, 2017).

Pescott, O., Peyton, J., Mountford, J., Onete, M. & Martinou, A. Non-native plant species GIS data from Cyprus Sovereign Base Areas, October 2015 and March 2017. NERC Environmental Information Data Centre https://doi.org/10.5285/7c84e06d-bb1a-4aac-b1d7-33c11310d8a0 (2017).

Pescott, O., Peyton, J. & Mountford, J. O. UKSBA Cyprus - Habitat Samples, 2019. Biological Records Centre https://doi.org/10.15468/c8p4qe (2020).

Pescott, O. L., Peyton, J. M. & Mountford, J. O. UKSBA Cyprus Plant Records 2018. Biological Records Centre https://doi.org/10.15468/xp6bam (2020).

Pescott, O. L., Peyton, J. M., Onete, M. & Mountford, J. O. UKSBA Cyprus - Quadrats 2015-2017. GBIF https://doi.org/10.15468/r4wyck (2020).

Plant Alert. Record invasive plants in your garden https://plantalert.org/ (2024).

Violaris, M., Vasquez, M. I. & Samanidou, A., Wirth, M. C. & Hadjivassilis, A. The mosquito fauna of the Republic of Cyprus: a revised list. JAMCA 25(2), 199–202, https://doi.org/10.2987/08-5793.1 (2009).

CNA/Ministry of Health. Aedes aegypti mosquitoes found in Dromolaxia, Ministry calls on citizens to cooperate https://www.cna.org.cy/en/article/3902789/aedes-aegyptimosquitoes-found-in-dromolaxia-ministry-calls-on-citizens-tocooperate (2022).

Peyton, J. et al. Using expert-elicitation to deliver biodiversity monitoring priorities on a Mediterranean island. PLoS ONE 17(3), e0256777, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256777 (2022).

Zenetos, A. et al. Alien species in the Mediterranean Sea by 2012. A contribution to the application of European Union’s Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). Part 2. Introduction trends and pathways. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 13, 328–352, https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.327 (2012).

Hadjikyriakou, G. & Hadjisterkotis, E. The adventive plants of Cyprus with new records of invasive species. Z. Jagdwiss. 48, 59–71, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02192393 (2002).

Christodoulou, C. S. The Impact of Acacia saligna Invasion on the Autochthonous Communities of the Akrotiri Salt Marshes (BSc (Hons) Dissertation, University of Central Lancashire 2003).

Papatheodoulou, A. et al. Distribution of two invasive alien species of Union concern in Cyprus inland waters. BioInv. Records 10(3), 730–740, https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2021.10.3.23 (2021).

Beton, D. & Huseyinoglu, M. F. First record of Plotosus lineatus (Thunberg, 1787) from Cyprus. In: Tiralongo, F. et al. New Alien Mediterranean Biodiversity Records (August 2022). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 23(3), 725-747 https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.31228 (2022).

Demetriou, J. et al. One of the world’s worst invasive alien species Wasmannia auropunctata (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) detected in Cyprus. Sociobiology 69(4), e8536, https://doi.org/10.13102/sociobiology.v69i4.8536 (2022).

Magory Cohen, T. et al. Accelerated avian invasion into the Mediterranean region endangers biodiversity and mandates international collaboration. J. Appl. Ecol. 59(6), 1440–1455, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14150 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Argyris Kallaniotis (Fisheries Research Institute, Hellenic Agricultural Organization Demeter) for his assistance on MEDITS project data (https://www.sibm.it/SITO%20MEDITS/principaleprogramme.htm). We would like to thank the UK Government through Darwin Plus (DPLUS056, 088, 124, 175, 200, 202) for funding our research on IAS as well as the British Forces Cyprus (RAF Akrotiri Sovereign Base Area) and the Joint Services Health Unit personnel for their constant support throughout these projects. Part of this project was compiled during COST Action: Alien Challenge (COST TD1209) during the short-term scientific missions of Dr Angeliki F Martinou, Jodey Peyton, Owen Mountford, Dr Marilena Onete and Dr Oliver Pescott as well as COST Action: Increasing understanding of alien species through citizen science (CA17122) during the short-term scientific mission of Mr Jakovos Demetriou. Helen Roy and Diana Bowler were also supported by the Natural Environment Research Council NC-UK Programme delivering national capability NE/Y006208/1. Helen Roy acknowledges support from the Natural Environment Research Council as part of the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology national and public good programme delivering national capability NE/R016062/1. Thank you also to Charlotte Johns who collated and reformatted CY.I.A.S. to the new CyDAS fields, and to Sara Boschi who checked and formatted several new datasets from our contributors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, assisted in coding and data visualisation, reviewed and edited the manuscript, assisted data collection, compilation, dataset review and update. A.F.M. Conceptualised the study, reviewed and edited the manuscript, assisted data collection, compilation, dataset review and update, supervised the project and secured funding. J.D., A.F.M., H.E.R. and A.Z. are joint lead authors given their contributions through the study with J.D. and A.F.M. sharing first authorship and H.E.R. and A.Z. sharing last authorship as senior leaders of the study. D.B. Led the main coding and data visualisation, reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.P. Reviewed and edited manuscript, assisted data collection, compilation, dataset review and update. O.L.P. Reviewed and edited the manuscript, assisted data collection, compilation, dataset review and update, and helped design the structure of the dataset/database. N.M. Reviewed and edited the manuscript, assisted data collection, compilation, dataset review and update. O.M. Reviewed and edited manuscript, assisted data collection, compilation, dataset review and update. M.O. Reviewed and edited the manuscript, assisted data collection, compilation, dataset review and update. M.S. Reviewed and edited the manuscript, assisted data collection, compilation, dataset review and update. B.R. Reviewed and edited the manuscript, led structure of the dataset/database. J.B. Reviewed and edited the manuscript, led structure of the dataset/database. H.E.R. Conceptualised the study, reviewed and edited the manuscript, supervised the project, and secured funding. A.Z. Conceptualised the study, reviewed and edited the manuscript, assisted data collection, compilation, dataset review and update, and supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Demetriou, J., Martinou, A.F., Bowler, D. et al. The Cyprus Database of Alien Species (CyDAS). Sci Data 12, 1881 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06151-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06151-w