Abstract

In the contemporary era, which is characterized by its emphasis on intelligence and technological advancement, the rapid evolution of machine vision technology has significantly enhanced the efficiency of artificial systems and yielded noteworthy achievements across numerous domains. Nevertheless, in certain specialized fields, such as the high-precision identification of the deterioration modes of stone cultural relics, the limitations of this technology persist. The primary rationale for this limitation is the lack of multi-dimensional and high-precision data support. In response, our team has collaboratively developed hyperspectral acquisition equipment with professional manufacturers and successfully established the world’s first hyperspectral dataset of stone cultural relics (HD-SC-1). This dataset encompasses 28,193 hyperspectral layers from China’s Dazu Rock Carvings. The spectral range of the dataset spans from 400 to 1000 nm, with an image resolution of 2048 × 2046 pixels. The dataset expands the scope of data on stone cultural relic deterioration and enriches the data resources for the protection of stone cultural relics, thereby revitalizing the conservation and restoration of world cultural heritage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

During the 19th century, there was growing awareness of the need to protect cultural relics and historical structures1. In the 20th century, the protection of cultural relics gradually transcended national boundaries, evolving into a global concern2. In the 21st century, technological advancements have given rise to innovative methods and mechanisms for cultural relics protection3,4,5,6. In recent years, the standards for cultural protection have grown increasingly stringent. As a result, the responsibility for safeguarding these treasures has shifted from traditional caretakers such as temples, aristocrats, and privileged classes to professional archaeologists, historians, and scientific researchers. In the modern era, the widespread integration of digital technology has significantly transformed protection methods, emphasizing efficiency and precision7. The successful implementation of these advanced protection measures, defined by their efficiency and precision, relies on the availability of high-quality datasets and sufficient data volume.

The construction and utilization of cultural heritage datasets represent a complex task, fraught with numerous challenges8,9,10,11. To address these challenges, the adoption of advanced technology is essential for ensuring the continuous protection and inheritance of cultural heritage. This process requires not only the meticulous collection of accurate data and the implementation of stringent data management protocols but also the ongoing innovation of methodologies and technological frameworks.

The scope of data pertinent to cultural relics protection is extensive, encompassing subjects ranging from a single historical painting to an entire historical building complex. All such entities fall within the domain of cultural protection. Dazu stone carving is an important part of it.

The cultural heritage dataset in question encompasses a variety of data types, each differing in structure12,13. In recent years, an increasing number of cultural institutions and enterprises have progressively made their datasets publicly available, fostering the exchange of cultural heritage data and improving the efficacy and success rate of cultural relics protection efforts14.

Hyperspectral imaging technology integrates the principles of optical imaging and spectral analysis, resulting in the creation of a three-dimensional dataset comprising spatial and spectral information. It is widely used in various disciplines and fields, including agriculture, biomedicine, industrial inspection, and cultural relics preservation15,16,17,18,19. Compared to traditional RGB imaging, the hyperspectral image offers the following advantages:

-

1)

Fusion of spectral information: The dimension of image information is enhanced, thus improving the accuracy of classification20,21,22.

-

2)

The difference of wave reflectivity: Strengthen data analysis from the perspective of material composition23,24.

The task of our team is to establish a hyperspectral cultural heritage data set and develop an automatic, fast, and accurate recognition model5,25. The automation of machine vision model training using hyperspectral datasets reduces the reliance on manual intervention26,27,28. The use of advanced algorithms and cutting-edge image preprocessing technologies has greatly enhanced the model’s recognition speed4,29,30,31. The improved precision in recognition capabilities is due to the cutting-edge equipment developed by our team, including hyperspectral acquisition instruments. These tools enable expanded data coverage, thereby enhancing recognition accuracy and the ability to capture fine details6,32,33.

In this groundbreaking study, we have successfully developed the first publicly available hyperspectral data set of stone relics. This initiative offers two main contributions: firstly, it enriches the existing dataset of stone cultural relics; secondly, it validates the effective integration of hyperspectral data with the preservation of stone cultural relics. This validation highlights the high-efficiency application potential of hyperspectral imaging in the field of cultural relics protection. Furthermore, this study has broadened the application scope of hyperspectral technology, advanced the development of classification algorithms based on hyperspectral images, and provided substantial technical support for cultural relics preservation. As a result, these achievements have significantly bolstered confidence and enthusiasm in the field of cultural heritage protection.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 reviews the construction and detection of datasets in image classification. Section 3 details the generation process of the datasets in this study. Section 4 discusses the application outcomes and experimental results of the dataset. Finally, Section 5 provides a comprehensive summary of the dataset’s advantages and potential application value.

Methods

Equipment introduction

To more accurately capture the details of deterioration, our team has collaborated with enterprises to develop a staring hyperspectral spectrometer (SHIS-N220). The instrument is divided into two acquisition systems: an indoor system and an outdoor system. The outdoor system includes a hyperspectral staring camera, a fixture, a tripod, an acquisition computer, and other components. The power supply mode uses an external power supply for the acquisition equipment, and the camera acquisition angle is adjusted manually using a knob and a joystick.

The indoor acquisition system consists of a hyperspectral staring camera, an indoor system console, and acquisition equipment, such as a computer. The power supply method is divided into two parts: the console utilizes residential electricity, while the spectral camera is powered by the acquisition equipment. The camera acquisition angle typically adopts an overhead shot, and the camera distance and the brightness of the light are controlled by the console button, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Data correction

Despite the spectrometer’s exceptional performance, it is subject to noise due to the impact of dark current during the acquisition process, which compromises the quality of the resulting data. The quality of ambient light also significantly influences the acquisition of images. To address these challenges, a whiteboard with a reflectivity of 99.99% is employed as a reference to neutralize the effect of ambient light and dark shooting correction is implemented to counteract the influence of dark current. It is imperative to note that this correction process must be executed individually, culminating in the formation of a comprehensive dataset, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Shooting challenges

The quality of the data obtained is contingent upon the limited protection status and access. Furthermore, the large number of tourists results in some data lacking a suitable shooting angle. During peak travel periods, some data lacks the corresponding environmental light, which poses a challenge to data collection. Nevertheless, the collection of high-quality data is prioritized.

Data Records

Presently, the public can access the hyperspectral dataset of stone relics through https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.2860691934. The system’s automated process for uploading files cancels folder attributes, resulting in a simpler naming method for more intuitive viewing of the uploaded files. The constructed dataset is multimodal, containing various data types, including spectral, image, spatial, color, and text data. It also includes images (.img/.tif), text (.md/.xlsx), and feature binary datasets. The datasets are divided into three separate folders according to content, as shown in Fig. 1.

The dataset exhibits a high degree of flexibility, supporting spectral data-based processing, image-based processing, and comprehensive processing of spectral and image combinations. The specific application mode can be adjusted according to the user’s research objectives, thereby meeting diverse research needs.

Data overview

The Dazu Rock Carvings were first constructed in the early Tang Dynasty and continued over several dynasties until the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Currently, 75 cultural relics protection grottoes are dispersed throughout 24 towns and streets in Dazu District. The Dazu stone carvings are regarded as the archetype of late grotto art in China, possessing invaluable historical, artistic, and scientific significance. In 1999, they were inscribed on the World Heritage List by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

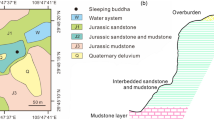

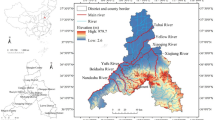

The reclining Buddha of Baoding Mountain (Sakyamuni Nirvana Scene) is an important component of the Dazu stone carvings, with a body measuring 31 meters in length, 3.2 meters in width, and 6.8 meters in height. The carving’s history can be traced back 851 years. A parallel can be drawn between the Dazu Baoding Mountain Buddha and the renowned Angkor Wat, as both sites share similar monsoon climate characteristics, topographical proximity, and comparable vegetation and ecosystem features. The deterioration patterns exhibited by the Baoding Mountain reclining Buddha closely mirror those observed in Angkor Wat, thereby validating the selection of Dazu Baoding Mountain as a representative sampling site. As shown in Fig. 2.

World famous grottoes environment similarity research map. Data sources35, download on https://www.worldclim.org/data/worldclim21.html. The Angkor Wat image data comes from the network. Average temperature (°C): The average temperature in January from 1970 to 2000. (Download number of the website: tavg 10 m-10 minutes). Precipitation (mm): The average precipitation in January of each year from 1970 to 2000. (Download number of the website: prec 10 m-10 minutes). Bioclimatic variables: The average value of each variable in January for the years 1970–2000. (Download number of the website: bio 10 m-10 minutes). Elevation: The data comes from SRTM elevation data. (Download number of the website: elev 10 m-10 minutes).

Hyperspectral data acquisition, correction, and machine vision application flow chart. (a–d) Outdoor acquisition system; (a) Hyperspectral camera; (b) Fixator knob; regulate loose and tight; (c) Fixer handle, adjust the camera angle; (d) Tripod. (a–g) Indoor acquisition system; (e) Indoor system console - simulating light sources; (f) Camera telescopic frame; (g) Console base, control camera moving up and down and light switch. An) Information to be tested after correction; Bn) identification result; n = 1, 2, 3, 4. DET: Detachment; FIML: Features Induced by Material Loss; DD: Discoloration & Deposit; BC: Biological Colonization. Where Ι is the corrected reflectance, R0 is the original reflectance, RD is the dark reference spectrum, and Rw is the white reference spectrum.

To provide a more comprehensive dataset on the deterioration of stone relics, we collected panoramic spectral data of the Buddha (Sakyamuni Nirvana Scene) at the site and sorted the data according to deterioration modes. In addition, we invited relevant staff from the Dazu Rock Carving Research Institute to participate.

The dataset under consideration contains a total of 28,193 spectral information layers, 233 visible light high-definition layers, 233 visible light spatial features, 466 visible light color spaces, and simple deterioration classification tables. The spectral wavelength range extends from 400 to 1000 nm, with a wavelength interval of 5 nanometers. The resolution is 2048 × 2046 pixels, and the adaptation algorithm is designed for classification, such as Att-RBF-RF4.

Data statistics

We chose the Dazu Rock Carvings as the first sampling point, using it as a starting point to gradually promote our hyperspectral dataset plan nationwide and eventually worldwide. The primary principle in creating the dataset is to represent the deterioration modes of stone cultural relics (the data format is strictly in accordance with the ENVI standard). Among them, discoloration and deposit, as well as features induced by material loss and detachment, are more prevalent.

The preliminary classification and collation of the dataset have been completed. The dataset spans 730 days, encompassing 233 high-resolution hyperspectral cubes, which collectively cover 28,193 independent layers. Of these, 11,616 layers are directly related to the statue, while 16,577 layers exhibit a weaker association. Additionally, the dataset meticulously documents five distinct deterioration modes. It is important to acknowledge that, due to the complexity of the environment, these deterioration patterns are interconnected and not entirely independent, which explains why the total number of deterioration pattern layers exceeds the total number of individual layers. To facilitate a comprehensive understanding and analysis of these deterioration patterns, we have provided a set of text datasets as a classification reference. Fig. 4 illustrates the structure and composition of the dataset in detail, providing a clear overview of the research.

Dataset Classification and Deterioration Mode Classification Diagram. The above figure represents the classification details of the data layer structure, where the x-axis represents the acquisition time, and the y-axis represents the number of layers. The following diagram shows the data deterioration classification summary. Given the complexity of the collection environment, it is reasonable to categorize the data based on the presence or absence of statues. Hyperspectral data is inherently a three-dimensional cube, which naturally includes some redundancy. Therefore, it is logical to adopt a layered classification approach to manage and analyze the data efficiently. The term ‘statue’ refers to a general category containing image information such as Buddha heads or statues. Specifically, if the layer data contains a Buddha image, it will be classified as a statue category; otherwise, it will be classified into a different category.

Technical Validation

Deterioration pattern classification

In this section, the HD-SC-1 dataset, proposed by the authors, is utilized for the training and evaluation of a classification model. The purpose of this model is to identify and evaluate deterioration patterns. Training the model generally involves several key steps, including the selection of the dataset, annotation, coding, fine-tuning, and recording.

In identifying more complex regional deterioration patterns, the selection of an appropriate dataset for model training is of particular importance. In comparison with efficient algorithms, high-quality datasets play a more significant role in improving model performance. Therefore, in model training, particular attention is paid to the degree of matching between the dataset and the training task, as well as the quality of the dataset, to ensure the accuracy of the training results and the reliability of the model. This strategy facilitates the construction of a more advanced recognition model and effectively enhances the accuracy of deterioration pattern recognition. It is noteworthy that the data feature set is derived entirely from raw hyperspectral data.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the process is delineated in meticulous detail, from the initial dataset preparation to the training and evaluation of the model. This methodical approach is meticulously designed to ensure the efficient training of models capable of accurately identifying deterioration patterns while preserving the simplicity and efficiency of the operational process.

Workflow Diagram for Data Acquisition, Processing, and Classification Training. Data distillation is a conventional method to improve the efficiency and accuracy of model operation. This paper makes full use of the existing information for model training. An) Information to be tested after correction; Bn) identification result; n = 1, 2, …, 5. The rightmost column is a confusion matrix that evaluates the accuracy of the model classification. CD: Crack & Deformation; DET: Detachment; FIML: Features Induced by Material Loss; DD: Discoloration & Deposit; BC: Biological Colonization.

The specific experiment was conducted using the following environment:

CPU: Intel(R) Xeon(R) E.

GPU: Quadro-p5200.

Operating System: Linux.

Frameworks and Libraries: TensorFlow 2; OpenCV 2.

Programming Language: Python 3.9.

To facilitate a more thorough examination of the deterioration modes, this study builds upon the prior research of the research team. The combination of 475 nm, 520 nm, 650 nm, 670 nm, 745 nm, and 750 nm is selected to form a true color map, which can more effectively identify the deterioration modes. The algorithm flow diagram is depicted in Fig. 6. The quality of the collected dataset is then assessed through a random sampling method, with the outcomes of this assessment incorporated into Fig. 7.

Experimental result analysis

To quantitatively evaluate the detection accuracy of the model, we used the F1 Score and Kappa Coefficient. These evaluation indicators provide a more accurate measurement of the model’s performance. The specific calculation formulas are as follows:

In formulas (2):

P0: represents the observed agreement, Pe: represents the expected agreement.

These metrics help us evaluate the model’s accuracy in identifying deterioration patterns in stone cultural relics more comprehensively.

The findings indicate that the model demonstrates a satisfactory capacity to identify the deterioration modes of stone cultural relics. The specific outcomes are enumerated in Tables 1, 2, and Fig. 7.

Considering the heterogeneity among identification models documented in prior studies, this study employs the \(\bar{F1}\) metric as the evaluation criterion. It is acknowledged that the performance of different models may vary, and direct comparisons may be limited. Nevertheless, it is hypothesized that the \(\bar{F1}\) score can serve as a reliable indicator of overall research quality to a reasonable extent. To this end, a quadratic average of the indicators obtained from the study was conducted and then compared with the indicators of the model in this study. This methodological approach ensures the comprehensiveness and representativeness of the evaluation.

An examination of the numerical indicators reveals that there are no significant differences between the models, suggesting that the models and datasets employed possess effective recognition capabilities. This result provides substantial evidence for the reliability of the model and the applicability of the dataset, thereby confirming the validity of our methodological approach and the scientific rigor of the research method.

Usage Notes

All uploaded hyperspectral data are rigorously verified to ensure their accuracy and reliability, and readers can download them directly. In terms of spectral data processing, commonly used methods include programming processing and professional software processing. Among them, programming processing is often realized by professional data packets such as Spectral Python, while software processing uses professional tools such as ENVI. It is assumed that the algorithm used has excellent performance. To further improve the fineness of the recognition effect, it is necessary to combine spectral information and spatial information to construct a more accurate recognition model.

Data availability

Presently, the public can access the hyperspectral dataset of stone relics through https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28606919. Please quote this article when you use it.

Code availability

The corresponding code and software are exposed to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28606919. In addition, you can also directly contact the author to obtain.

References

Jokilehto, J. A Century of Heritage Conservation. Journal of Architectural Conservation. 5(3), 14–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/13556207.1999.10785249 (1999).

Li, L., Tang, Y. Towards the Contemporary Conservation of Cultural Heritages: An Overview of Their Conservation History. Heritage. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7010009 (2024).

Blake, J. On Defining the Cultural Heritage. International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 49(1), 61–85, https://doi.org/10.1017/S002058930006396X (2000).

Peng, L., Bo, W., Yang, H. & Li, X. Deep learning-based image compression for enhanced hyperspectral processing in the protection of stone cultural relics. Expert Systems with Applications. 271, 126691, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126691 (2025).

Chen, C., Yang, H., Li, X., Zhao, G. & Ni, J. Hyperspectral estimation method for deterioration of rock carvings in the humid regions of southern China. Heritage Science. 12(1), 105, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01226-0 (2024).

Yang, H., Chen, C., Ni, J. & Karekal, S. A hyperspectral evaluation approach for quantifying salt-induced weathering of sandstone. Science of The Total Environment. 885, 163886, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163886 (2023).

Gîrbacia, F. An Analysis of Research Trends for Using Artificial Intelligence in Cultural Heritage. Electronics. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13183738 (2024).

Mäkelä, E., Hyvönen, E. & Ruotsalo, T. How to deal with massively heterogeneous cultural heritage data – lessons learned in CultureSampo. Semantic Web. 3, 85–109, https://doi.org/10.3233/SW-2012-0049 (2012).

Alma’aitah, W. Z. A., Talib, A. Z. & Osman, M. A. Opportunities and challenges in enhancing access to metadata of cultural heritage collections: a survey. Artificial Intelligence Review. 53(5), 3621–46, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-019-09773-w (2020).

Bellavia, F., Colombo, C., Morelli, L., Remondino, F. Challenges in Image Matching for Cultural Heritage: An Overview and Perspective. In: Mazzeo PL, Frontoni E, Sclaroff S, Distante C, editors. Image Analysis and Processing. ICIAP 2022 Workshops. p. 210–22 Cham: Springer International Publishing; (2022).

Remondino, F. & Rizzi, A. Reality-based 3D documentation of natural and cultural heritage sites—techniques, problems, and examples. Applied Geomatics. 2(3), 85–100, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12518-010-0025-x (2010).

Origlia, A., Rossi, S., Martino, S. D., Cutugno, F., Chiacchio, M. L. Multiple-source Data Collection and Processing into a Graph Database Supporting Cultural Heritage Applications. J Comput Cult Herit. 2021;14(4):Article 55. https://doi.org/10.1145/3465741.

Alkemade, H. et al. Datasheets for Digital Cultural Heritage Datasets. Journal of Open Humanities Data. https://doi.org/10.5334/johd.124 (2023).

Dressen, A. Cultural Heritage Data for Research–An Introduction. Open Library of Humanities. 11(1) (2025).

Shuai, L., Li, Z., Chen, Z., Luo, D. & Mu, J. A research review on deep learning combined with hyperspectral Imaging in multiscale agricultural sensing. Comput Electron Agric. 217, 108577, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2023.108577 (2024).

Zhang, B. et al. Progress and Challenges in Intelligent Remote Sensing Satellite Systems. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing. 15, 1814–22, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2022.3148139 (2022).

Shahid, K., Akeel, Q., Umar, F., Muhammad, S. & Asif Ali, L. Hyperspectral Imaging: A Review and Trends towards Medical Imaging. Current Medical Imaging. 19(5), 417–27, https://doi.org/10.2174/1573405618666220519144358 (2023).

Luo, L. et al. Airborne and spaceborne remote sensing for archaeological and cultural heritage applications: A review of the century (1907–2017). Remote Sensing of Environment. 232, 111280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111280 (2019).

Yang, H., Cappitelli, F. & Li, X. Pollution gradients shape structure and functions of stone heritage bacterial communities at global scale. Science of The Total Environment. 971, 179087, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.179087 (2025).

Dong, W. et al. Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution via Non-Negative Structured Sparse Representation. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 25(5), 2337–52, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2016.2542360 (2016).

Mei, S. et al. Hyperspectral Image Spatial Super-Resolution via 3D Full Convolutional Neural Network. Remote Sensing. 9(11), 1139 (2017).

Xiang, P., Ali, S., Jung, S. K. & Zhou, H. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection With Guided Autoencoder. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing. 60, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2022.3207165 (2022).

Lu, B., Dao, P. D., Liu, J., He, Y. & Shang, J. Recent Advances of Hyperspectral Imaging Technology and Applications in Agriculture. Remote Sensing. 12(16), 2659 (2020).

Moharram, M. A. & Sundaram, D. M. Land use and land cover classification with hyperspectral data: A comprehensive review of methods, challenges and future directions. Neurocomputing. 536, 90–113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2023.03.025 (2023).

Li, X., Yang, H., Chen, C., Zhao, G. & Ni, J. Deterioration identification of stone cultural heritage based on hyperspectral image texture features. Journal of Cultural Heritage. 69, 57–66, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2024.07.011 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. A Deep Learning-Based Approach for Automated Yellow Rust Disease Detection from High-Resolution Hyperspectral UAV Images. Remote Sensing. 11(13), 1554 (2019).

Hong, D., Yokoya, N., Ge, N., Chanussot, J. & Zhu, X. X. Learnable manifold alignment (LeMA): A semi-supervised cross-modality learning framework for land cover and land use classification. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. 147, 193–205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2018.10.006 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Leaf area index estimation model for UAV image hyperspectral data based on wavelength variable selection and machine learning methods. Plant Methods. 17(1), 49, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-021-00750-5 (2021).

Ou, X., Liu, L., Tu, B., Zhang, G. & Xu, Z. A CNN Framework With Slow-Fast Band Selection and Feature Fusion Grouping for Hyperspectral Image Change Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing. 60, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2022.3156041 (2022).

Zeng, F. et al. Rapid detection of white blood cells using hyperspectral microscopic imaging system combined with Multi-data Faster RCNN. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 389, 133865, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2023.133865 (2023).

Bhatti, U. A. et al. MFFCG – Multi feature fusion for hyperspectral image classification using graph attention network. Expert Systems with Applications. 229, 120496, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120496 (2023).

Yang, H., Ni, J., Chen, C. & Chen, Y. Weathering assessment approach for building sandstone using hyperspectral imaging technique. Heritage Science. 11(1), 70, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-00914-7 (2023).

Shafique, A., Cao, G., Khan, Z., Asad, M. & Aslam, M. Deep Learning-Based Change Detection in Remote Sensing Images: A Review. Remote Sensing. 14(4), 871 (2022).

Peng, L. HD-SC-1: Hyperspectral Dataset for Stone Cultural Relics. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28606919 (2025).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology. 37(12), 4302–15, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52179096) and Chongqing Talent Program Young Top Talents (No. cstc2024ycjh-bgzxm0047).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Haiqing Yang: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft. Lixin Peng: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft. Xingyue Li, Chiwei Chen, Shide Liu, Gang Zhao: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, H., Peng, L., Zhao, G. et al. Hyperspectral data set of stone cultural relics in high-precision machine vision scene. Sci Data 12, 1887 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06158-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06158-3