Abstract

To address the scarcity of high-quality instance segmentation data for the unique architecture of high-density East Asian cities, this paper introduces the Connected Building Landscape dataset, a vital resource for urban planning, architectural analysis, and computer vision tasks. Researchers can utilize this dataset to train and benchmark a wide range of segmentation models, enabling a deeper understanding of East Asian architectural morphology. This detailed analysis provides urban planners with more precise tools and facilitates the generation of the hazard distribution maps or cultural heritage preservation priority reports. The dataset contains 2,801 JPEG images (1024 × 768 pixels) with polygonal segmentation masks, capturing diverse architectural styles and complex spatial layouts along National Route 1 from Tokyo to Osaka. All annotations are provided in a standard JSON format for easy model integration. Baseline experiments on models like Mask R-CNN and Mask2Former validate the dataset’s quality and robustness for its intended tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

As global urbanization accelerates, high-density cities (HDCs) have become the predominant form of human settlement, characterized by vertical development, a mix of functions, and a compact layout1,2. Recent global studies confirm this trend has intensified, shifting from lateral expansion to vertical development, or ‘building up’, particularly in Asian cities where it creates unique cityscapes3. The Connected Building Landscape (CBL)4 itself refers to the continuous and visually complex landscape created by densely located buildings. It is defined by the intricate way building facades are spatially located, presenting diverse architectural styles and complex relationships when observed from the street level. While this CBL morphology is a feature of many urban areas, the context of Japan offers a distinct example, where these forms are also profoundly influenced by regulations like the ’Sky Ratio’ act5, motivating the creation of our Connected Building Landscape dataset. Furthermore, its utility is highly transferable. For many developing nations facing rapid vertical urbanization but lacking comprehensive data, SVI-based analysis provides a pragmatic and cost-effective tool for urban planners6. Understanding and analyzing this landscape is critical. HDCs face significant sustainability challenges7.Such as mitigating the urban heat island effect through strategic greening and addressing the varied impacts of air pollution8. Additionally, the physical characteristics of the CBL, such as obstructed sight lines and building proximity, can have tangible psychological effects on residents9.Therefore, accurately capturing and segmenting the components of the CBL is a foundational step. This work enables the development of data-driven solutions for more resilient and livable high-density urban environments.

Street View Imagery (SVI) is a powerful tool for analyzing the built environment at the human scale10. The fusion of large-scale image data with artificial intelligence has given rise to the field of Urban Visual Intelligence, a new paradigm that is reshaping how researchers perceive, measure, and understand cities, allowing for data-driven reassessments of classic urban theories11. A key application of this approach is the ability to move beyond landmarks and quantify a city’s unique visual identity from its everyday scenes, revealing subtle differences that define its character?. However, systematic reviews show that to fully harness the potential of these advanced methods, there is a critical need for standardized datasets to enable more accurate and reliable auditing of the built environment, particularly tools adapted for the contexts of developing countries12. Developing such resources is therefore a critical step to provide scalable solutions for evaluating vital metrics like walkability and social inequality13, and to advance this emerging field of research.

To address this critical gap in available resources, this study selected the urban corridor along Japan’s National Route 1 as our case study area. This region connects the major metropolitan areas of Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya and serves as a quintessential example of high-density East Asian urban development. The buildings and streetscapes along this historic route present a complex tapestry of building styles. They embody a balance between modern spatial efficiency and cultural heritage protection, making the area an ideal setting to capture real-world urban segmentation challenges. It is within this context that this study introduce the CBL dataset. By providing 2,801 street-view images with meticulous, manually-created polygonal annotations for building instance segmentation, CBL offers a novel and necessary resource tailored to this specific environment. Its primary contribution lies in its unique focus on East Asian building styles and complex, dense spatial layouts. This directly addresses the geographical and task-specific limitations of existing datasets. Crucially, the novelty of CBL is in the visual complexity captured within each image. Unlike datasets that may only feature isolated structures, a typical image in CBL presents a dense scene with multiple, often overlapping, and visually connected buildings. These scenes are characterized by significant partial occlusion from street furniture, diverse architectural functions, and intricate spatial arrangements. Therefore, CBL provides a challenging benchmark designed to test an algorithm’s ability to handle real-world urban complexity and distinguish between closely packed instances. This makes it a vital resource. It can be used to develop more robust computer vision models and also by urban planners seeking to analyze the fine-grained texture of the built environment.

Methods

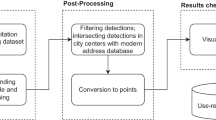

The overall workflow of our methodology is illustrated in Fig. 1. The process begins with the acquisition of street-view imagery using the Google Street View API and OpenStreetMap road network, followed by a meticulous annotation and quality check process conducted by a team of professionals from the architectural field to create the Connected Building Landscape (CBL) dataset. Subsequently, the dataset is partitioned into training, validation, and test sets for fine-tuning various instance segmentation models. Finally, to establish its unique value, a comparative analysis is performed to position the CBL dataset against standard benchmarks such as COCO, Cityscapes, and ADE20K, using metrics like “Proportion of Dense Instances” and “CBL Scale Instance Number”.

Data Source and Scope

The dataset for this study was constructed to capture diverse and dense urban architectural features representative of East Asian cityscapes. Image data was sourced from Google Street View (www.google.com/streetview), a database comprising high-resolution photographs captured by Google’s Street View vehicle (Fig. 2) along its travel routes. The specific location for this study was Japan National Route 1. A systematic equidistant sampling methodology was employed, establishing sampling points at fixed 15-meter intervals based on the OpenStreetMap (www.openstreetmap.org) road network. For each sampling point, the orientation of its corresponding road segment-the bearing, or angle relative to true north-was calculated. Subsequently, using the coordinates of these points and the two calculated perpendicular headings (bearing ± 90°), the corresponding Street View images were programmatically acquired via the Google Street View API. Any points where imagery was unavailable were omitted from the sample. The images were sourced specifically from the years 2015 to 2021 to include a variety of lighting, seasonal, and weather conditions. To balance file size with visual clarity, all images were standardized to a resolution of 1024 x 768 pixels.

System used to collect the dataset images. Google Street View collection vehicle. https://www.google.com/intl/ja/streetview/how-it-works.

Data Scale, Format, and Organization

This dataset comprises 2,801 JPEG images, all standardized to a resolution of 1024 × 768 pixels. This study manually annotated every identifiable building in each image using labelme (version 5.1), generating a corresponding JSON file with polygonal instance masks. For ease of use, all data is organized within a top-level folder named “Connected_Building_Landscape”. The dataset is randomly partitioned into three subsets: a training set (70%), a validation set (20%), and a test set (10%). To ensure compatibility with common computer vision pipelines, This study provide a master COCO-format annotation file (e.g., all_train_info.json) for the training set. Additionally, a metadata.csv file records basic information for each image, as detailed in Table 1.

Annotation Protocol and Quality Assurance

A comprehensive annotation protocol was developed to guide the annotators. The protocol outlined criteria for identifying building facades, handling partially occluded structures, and distinguishing buildings from non-building elements. For example, if a building was partially obscured by a tree or street furniture, only the clearly visible portion of the facade was segmented. Instances where the visible area was insufficient to confidently identify a distinct building were excluded. Building facades and permanently attached external features (e.g., billboards, signage) were treated as a single building entity.

The researcher assembled an annotation team of seasoned professionals from the architectural field. All annotators were first trained on our standardized protocol, which involved reviewing sample images and benchmark cases. A pilot study was used to test and improve these guidelines for clarity and robustness. The researcher then quantitatively evaluated the quality of our annotations. On 200 randomly selected images, the average Inter-annotator Agreement, measured by Intersection over Union (IoU), reached approximately 0.85 ± 0.03. To maintain this high standard throughout the process, a senior annotator also executed periodic quality checks. For specific annotation examples, please refer to Fig. 3, which shows the masks for the images.

Data Preprocessing and Standards

No additional preprocessing steps (e.g., normalization, cropping) were applied beyond setting the final resolution to approximately 1024 × 768 pixels. By retaining this consistent and reasonably detailed resolution, this paper provide a dataset that closely reflects real-world conditions while remaining accessible for computational analysis. Subsequent researchers are encouraged to apply their own pre-processing techniques, such as resizing, normalizing, or data augmentation, as needed.

Dataset Analysis and Positioning

To fairly evaluate the CBL dataset and other widely-used datasets, this research adopts “Instance Density” and “CBL scale instance number” as a metric.

Our analysis shows that the CBL dataset, which focuses on the class of buildings, achieves an instance density of approximately 4.34 instances per image. This study calculated the instance densities for mainstream classes in other datasets and projected them onto the same scale as CBL. As shown in Fig. 4, the total count of ‘building’ instances in CBL (12,151) ranks highly among all compared categories. This count is not only comparable to the number of ‘person’ instances in Cityscapes14 (11,996) but is also several times greater than the ‘person’ instance counts in COCO15 (6,215) and ADE20K16 (3,112).

Next, as detailed in Table 2, this table clearly shows that CBL is the only dataset focused on East Asian (Japanese) architecture and the only one providing fine-grained annotations of the building instance. More importantly, CBL exhibits a significant difference in scene density compared to other datasets. To quantitatively capture this property,this study calculated the “per-instance separation distance” and “Proportion of Dense Instances” for each datasets. And Our analysis targets only instances with neighbors; solitary instances in an image are excluded from this calculation. The calculation code and results of all the above metric are available on: https://github.com/SonginMoonlight/CBL/tree/main/data_analysis.

-

Per-instance separation distances. This process involves vectorizing each instance’s segmentation mask into a polygon and then computing the minimum distance to the boundary of its nearest neighbor of the same class within the same image. Figure 5 provides some visual examples of this process.

-

Proportion of Dense Instances. The number of instances with a separation distance of less than 10 pixels, as a percentage of the total number of instances with a separation distance of less than 40 pixels. In other words, this ratio reflects what proportion of all “proximal” (<40px) instances are “highly dense” (<10px). Based on visual analysis, the researcher selected 10 pixels and 40 pixels as key thresholds. A distance of less than 10 pixels typically corresponds to severe occlusion or physical contact, while 40 pixels serves as the upper bound for a “proximal” relationship, beyond which instances are generally clearly separated. The design of this metric allows our comparison to focus on the intrinsic distributional differences between datasets in handling high-density scenes.

The results clearly show that 84.82% of proximal building instances in the CBL dataset have a separation distance of less than 10 pixels. This proportion is similar to that of vehicle instances in Cityscapes(85.50%) and higher than the corresponding values for any mainstream instance in the other datasets.

In summary, our comparative analysis shows that the CBL dataset achieves a scale comparable to, or even exceeding, that of the primary classes (e.g., persons, cars) in mainstream benchmarks like COCO and Cityscapes. More importantly, CBL fills a critical gap in many ways. It is the first building instance dataset focused on dense East Asian architectural scenes. Our proposed “Proportion of Dense Instances” substantiates this: a remarkable 84.82% of proximal building instances in CBL are “highly dense” (spacing < 10px). This proportion is similar to that of vehicle instances in the notoriously crowded Cityscapes and higher than the density of common objects in other datasets. This presents a novel segmentation challenge that cannot be replicated with existing datasets. Therefore, with its substantial scale, unique scene content, and a quantifiable, unprecedented level of challenge, CBL provides an indispensable new platform for research in instance segmentation in dense scenes, powerfully advancing the development of the field. To ensure semantic continuity with the embedding analysis, the colouring metrics mirror the dataset-level definitions: proximity and contiguity instantiate the nearest–neighbour density at the per-image level; instance count and footprint coverage reflect intensity and granularity; boundary complexity corresponds to shape irregularity via \({\rm{perimeter}}/\sqrt{{\rm{area}}}\).

Visualisation of Learned Representations Pipeline

To visualize and interpret the learned feature space, we implemented the following data processing pipeline.

First, encoder features were extracted from a Mask2Former model with a COCO-pre-trained Swin-Large backbone. The model configuration was identical to that of the final model reported in the Technical Validation section (Table 3). These high-dimensional features were then processed sequentially: they were globally averaged over spatial dimensions, L2-normalised, and finally reduced to 50 components using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for subsequent t-SNE visualisation.

To give semantic meaning to the embedding, the points were colored according to four metrics derived from the image annotations. The first metric: Contiguity Level, was computed from pairwise adjacency via binary dilation (three iterations). The second: Proximity Score, is a continuous score in the [0, 1] range defined as the fraction of adjacent instance pairs under the same operator, which was cross-checked with centroid nearest–neighbour distances. The third metric: Boundary Complexity, was measured using the formula \({\rm{perimeter}}/\sqrt{{\rm{area}}}\), calculated per-instance and then averaged per image. Finally, two related metrics captured the scene’s characteristics: Instance Count, representing the number of building instances, and Footprint Coverage, the proportion of image pixels covered by their masks. This analysis was performed on the combined training and validation sets, which include a total of 2,801 images.

Data Record

This dataset provides metadata for 2,801 street images along Japan’s National Route 1. For each image, the metadata includes geographic coordinates, timestamps, and other geospatial information. To respect copyright, the image files themselves are not distributed. Instead, this metadata allows users to retrieve the images from their original source. The dataset is accompanied by corresponding annotation files in JSON format. The complete package, containing all metadata and annotations, is available at https://zenodo.org/records/17010720 under the CC-BY license.

The data is organized within a top-level directory, Connected_Building_Landscape, which is divided into the following subfolders:

-

train/: 1,960 images (70%)

-

Per-image annotations: Individual JSON files paired with each image (e.g., 2_1.json)

-

Aggregated annotations: COCO-format file CBL_train.json with whole annotated information.

-

-

val/: Contains all JSON files corresponding to 560 images (20%) and CBL_val.json.

-

test/: Contains all JSON files corresponding to 281 images (10%) and CBL_test.json.

Technical Validation

Experimental Setup

To quantify the fundamental contribution and technical necessity of the proposed CBL dataset, a dataset-level ablation study was conducted. This approach isolates the impact of the CBL dataset by comparing model performance before and after fine-tuning, effectively enabling the ablation (i.e., removal) of the CBL training data’s influence to directly measure its contribution.

The validation experiments utilize two widely-recognized instance segmentation frameworks-Mask R-CNN17 and Mask2Former18-using a variety of ImageNet pre-trained backbone networks, including ResNet-50, ResNet-10119, and Swin Transformers (Swin-T, Swin-L)20. All models were sourced from their official implementations in the Detectron2 library (https://github.com/facebookresearch/Mask2Former/tree/main), using publicly available pre-trained weights from large-scale datasets such as COCO, Cityscapes, and ADE20K.

Evaluation Protocol and Metrics

The ablation study comprises two distinct experimental conditions designed to evaluate the impact of CBL:

-

Condition 1 (CBL Ablated): In this baseline condition, the pre-trained models are evaluated directly on the CBL test set without any fine-tuning on the dataset. This condition measures the models’ performance and their capability to segment building instances.

-

Condition 2 (CBL Applied): In this condition, the same pre-trained models are fine-tuned on the CBL training set and subsequently evaluated on the same CBL test set.

Model performance is evaluated from two perspectives: segmentation accuracy, measured by the standard Average Precision (AP)15, and inference efficiency, measured in seconds per image. Higher AP values denote superior accuracy.

Hyperparameter Settings

To ensure a fair comparison across experiments, a uniform training strategy was adopted for all fine-tuning procedures. Key hyperparameters were held constant for all models where applicable.

For the optimization of the deep learning models, architecture-specific strategies were employed, informed by preliminary experiments. Specifically, the Adam optimizer21 was selected for ResNet-based models, while the AdamW optimizer22 was utilized for Swin Transformer architectures, as this configuration was empirically determined to yield the best performance. All models were trained with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−3. A batch size of 64 was used during the training phase, whereas a batch size of 32 was employed for inference. The models were trained for a maximum of 50 epochs, with an early stopping protocol in place: training was terminated if the validation loss did not improve for 500 consecutive steps.

Hardware and Software Environment

All experiments were conducted on an A800 GPU with 80 GB of memory. The computational platform consisted of 14 CPU cores, 100 GB of system RAM, and 50 GB of available storage. Training time for each model ranged from 0.5 to 18 hours, depending on architecture complexity. The software environment comprised Python 3.9, PyTorch 2.3, and CUDA 12.1.

Results and Analysis

The results of the dataset-level ablation study, presented in Table 3, demonstrate the critical contribution of the CBL dataset.

The most critical finding from the validation study is the fundamental necessity of the CBL dataset itself. In the baseline (CBL Ablated) condition, it was revealed that all pre-trained models, irrespective of their architecture or source dataset, achieved an Average Precision (AP) of approximately 0 on the CBL test set. In contrast, after being fine-tuned on CBL (the CBL Applied condition), all models showed a substantial increase in performance. For instance, the Mask2Former with a Swin-L backbone pre-trained on COCO achieved an AP of 48.81. This transition from near-zero performance to competent segmentation is solely attributable to the introduction of the CBL dataset. This finding strongly supports the central hypothesis that a new, specialized dataset is not just beneficial, but necessary to tackle the challenge of East Asian architectural scene segmentation. The visual results in Fig. 6 further corroborate this quantitative conclusion, showing models transitioning from producing no meaningful output to generating precise instance masks.

While all models benefited critically from CBL, the ablation study also revealed significant differences in the robustness of various backbones during this domain adaptation process. The Swin Transformer series backbones consistently demonstrated superior adaptability, maintaining high performance levels with minimal degradation. Conversely, the ResNet backbones, particularly within the Mask2Former framework, experienced a notable struggle to adapt, as indicated by their comparatively lower final AP scores relative to their high potential shown on the original source datasets.

It is hypothesized that this performance disparity stems from architectural differences. The traditional convolutional structure of ResNet, with its localized receptive fields, may struggle to capture the complex global context and long-range dependencies inherent in dense, repetitive building facades. In contrast, the Swin Transformer’s window-based multi-head attention mechanism is inherently better suited for modeling such complex spatial relationships, leading to more stable and effective knowledge transfer during fine-tuning.

First, unlike existing datasets, Connected Building Landscape (CBL) specifically targets high-density East Asian architectural scenes in street-view imagery. Its “Proportion of Dense Instances” is comparable to dominant categories in mainstream datasets (e.g., Cityscapes) and significantly exceeds others (e.g., COCO, ADE20K). Our findings suggest that Swin backbones exhibit exceptional stability during fine-tuning. This is attributed to the proficiency of their multi-head attention mechanism in capturing long-range spatial dependencies. In contrast, ResNet backbones are limited by their inherent local receptive fields when processing dense East Asian architectural scenes, leading to a decline in their average performance after fine-tuning. Consequently, the application of Swin on dense datasets like CBL is particularly crucial, as it allows for the learning of more robust and transferable representations, thereby enabling more effective generalization to real-world complex street-view scenes.

Second, by utilizing the instance segmentation masks and building category labels within CBL, a model can be trained to precisely delineate individual buildings within dense scenes. This enables automated analysis based on building contours, forms, and density distribution. For example, the generated instance masks provide the fundamental geometric data necessary for urban morphological analysis, which can be further categorized based on the assigned building types. This allows for the automated generation of detailed urban development maps and architectural density reports.

While CBL addresses a critical gap in existing datasets, it still has limitations. The geographic coverage is limited - all data comes from Japan National Route 1. To address this, future work will focus on expanding the dataset to include imagery from major metropolitan areas in Japan, as well as key cities across other East Asian countries, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Seoul. The label categories are also too narrow to support comprehensive urban spatial analysis. Meanwhile, computer vision models are advancing rapidly: OneFormer23 achieves state-of-the-art accuracy through its unified multi-task architecture, SAM24 enables zero-shot segmentation across domains (like adapting from medical images to satellite data), and SEEM25 generates combined masks through text prompts or click interactions.While a direct performance comparison with these models was constrained by both computational resources and a difference in our research objectives, our dataset remains a valuable resource for validating their performance in a challenging domain.

To overcome the current limitations of CBL, we plan to expand the dataset’s geographic coverage, refine label granularity, and simultaneously conduct validation with new models. Specifically, we will expand our data collection to cover diverse urban environments, including major metropolitan areas and contrasting shrinking cities. This expansion aims to capture a wide array of complex scenarios, such as high-density commercial districts with severe occlusion, and unique urban forms characterized by low-rise and decaying architecture.Moving beyond common objects like pedestrians and billboards, we will focus on more challenging categories directly relevant to urban research. Specifically, we will perform detailed annotation for building materials (e.g., concrete, glass, wood, brick), and facade conditions (e.g., cracks, stains, graffiti), and building function (e.g., residential, commercial, mixed-use, temples). This data will directly support applications in architectural risk assessment, urban morphological analysis, and sustainability studies, thereby transforming CBL from a foundational instance segmentation dataset into a powerful tool for urban research and planning.

Furthermore, the dataset’s modest size (2,801 images) and dense annotations make it an ideal benchmark for evaluating model performance in challenging low-data scenarios. This positions CBL as a crucial testbed for few-shot and zero-shot learning. Future work can, for instance, evaluate the zero-shot performance of large foundation models like the Segment Anything Model (SAM) on this unique architectural domain using only point or text-based prompts. The dataset is also well-suited for testing few-shot fine-tuning strategies, where a model is adapted using only a small fraction of the training data. Success in such scenarios would not only validate the capabilities of modern vision models but also significantly enhance the applicability of the CBL framework to other high-density urban contexts where large-scale data collection is impractical.

Embedding Visualisation of Learned Representations

The visualisations in Fig. 7 and Fig. 8 show a clear structure in the learned feature space. We can see a distinct left-to-right pattern based on the Contiguity Level, moving from scenes with Isolated or Loosely distributed buildings to those that are Moderately or Highly contiguous. The Proximity map shows this same pattern: areas with high contiguity also have high proximity scores. Furthermore, Boundary Complexity is also higher in these high-contiguity zones. This is consistent with the irregular shapes created by touching roofs and narrow gaps, and it shows the model uses shape as an important feature.

The plots also reveal a clear trade-off between the number of instances and their size. In the Instance Count & Coverage visualisation, scenes with high footprint coverage (shown by larger markers) tend to have fewer instances (shown by lighter colours), and vice versa. For example, coverage differs significantly across the different contiguity levels (Kruskal-Wallis H = 534.25, p ≈ 1.8 × 10−115). We also found a strong negative association between proximity and instance count (Spearman ρ = − 0.765, p ≈ 0), which indicates that dense areas typically contain fewer but larger buildings.

Fine-tuning the model on our dataset makes this feature space even better structured. After fine-tuning, the boundaries between the different contiguity groups become sharper, and the data points within each group become more consistent. This improvement is confirmed by metrics like the PCA explained variance (increasing from 71.86% → 74.36%) and the t-SNE KL divergence (decreasing from 1.6735 → 1.5939). Most importantly, this improvement in the feature space directly matches the large performance jump on the CBL test set (e.g., Mask2Former–Swin-L reached an AP of 48.81). These findings suggest that the ability to represent contiguity, coverage, and boundary complexity together is the key to good instance segmentation in dense East Asian cityscapes.

Usage Notes

This dataset contains images specifically designed for building instance segmentation, and we actively encourage other researchers to reuse and build upon it for related tasks. For data analysis, we recommend employing well-established frameworks such as Detectron2, which are particularly well-suited for instance segmentation tasks. These frameworks, available in both TensorFlow and PyTorch, can be readily adapted for training models on the provided dataset. Additionally, it is worth noting that the current SOTA model for such tasks is OneFormer; however, due to the high computational costs associated with fine-tuning this model, it was not feasible within the scope of this study. Nonetheless, employing OneFormer on the dataset has the potential to yield even better results. Data augmentation methods such as random cropping, flipping, and rotation are highly recommended to enhance model robustness. When utilizing our dataset for training purposes, employing data augmentation strategies is deemed essential. Indeed, within our own data validation processes, we have incorporated these augmentation methods to bolster the model’s resilience and generalizability.

Data availability

The Connected Building Landscape dataset described in this study, including all metadata and annotation files, is publicly available in the Zenodo database under a CC-BY license. The dataset can be accessed at https://zenodo.org/records/17010720.

Code availability

To ensure full reproducibility, the source code and implementation details for all analyses in this manuscript are available at: https://github.com/SonginMoonlight/CBL. This includes: The scripts for all metric calculations, statistics, and the generation of visualisation results. The necessary components to reproduce the results of the selected fine-tuned models presented in the “Technical Validation” section.We recommend adapting this dataset to target instance segmentation frameworks (e.g., Detectron2 or MMDetection) through structural modifications enabled by the provided format conversion toolkit in different segmentation frameworks.

References

Miao, P. (ed.) Public Places in Asia Pacific Cities: Current Issues and Strategies, vol. 60 of GeoJournal Library (Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2001).

Zhang, J. et al. Evaluating environmental implications of density: A comparative case study on the relationship between density, urban block typology and sky exposure. Automation in Construction 22, 90–101, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2011.06.011 (2012). Planning Future Cities-Selected papers from the 2010 eCAADe Conference.

Frolking, S., Mahtta, R., Milliman, T., Esch, T. & Seto, K. C. Global urban structural growth shows a profound shift from spreading out to building up. Nature Cities 1, 555–566 (2024).

Zheng, Z. Connected Building Landscape_dataset [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17010720 (2025).

Kirita, H., Ohsawa, Y., Hasuka, F. & Nakagawa, M. Effect of sky exposure rate regulation on building layout. Journal of Architecture and Planning(Transactions of AIJ) 71–78 (2007).

Ying, Y. et al. Toward 3d hedonic price model for vertically developed cities using street view images and machine learning methods. Habitat International 156, 103288 (2025).

Yao, M., Yao, B., Cenci, J., Liao, C. & Zhang, J. Visualisation of high-density city research evolution, trends, and outlook in the 21st century. Land 12, 485, https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020485 (2023).

Ng, E., Chen, L., Wang, Y. & Yuan, C. A study on the cooling effects of greening in a high-density city: An experience from hong kong. Building and Environment 47, 256–271, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2011.07.014 (2012). International Workshop on Ventilation, Comfort, and Health in Transport Vehicles.

Chung, W. K. et al. On the study of the psychological effects of blocked views on dwellers in high dense urban environments. Landscape and Urban Planning 221, 104379, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104379 (2022).

Li, Y., Peng, L., Wu, C. & Zhang, J. Street view imagery (svi) in the built environment: A theoretical and systematic review. Buildings 12, 1167 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Urban visual intelligence: Studying cities with artificial intelligence and street-level imagery. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 114, 876–897 (2024).

Dai, S., Li, Y., Stein, A., Yang, S. & Jia, P. Street view imagery-based built environment auditing tools: a systematic review. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 38, 1136–1157 (2024).

Gebru, T. et al. Using deep learning and google street view to estimate the demographic makeup of neighborhoods across the united states. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 13108–13113 (2017).

Cordts, M. et al. The cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2016).

Lin, T.-Y. et al. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 740–755, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10602-1_48 (2014).

Zhou, B. et al. Semantic understanding of scenes through the ade20k dataset. International Journal of Computer Vision 127, 393–408, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-018-1140-0 (2019).

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P. & Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2961–2969, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.322 (IEEE, 2017).

Cheng, B., Schwing, A. & Schwing, A. G. Masked-attention mask transformer for universal image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 1290–1299 (2022).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 770–778, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 (Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016).

Liu, Z. et al. Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 10012–10022, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00986 (Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 2021).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. In Bengio, Y. & LeCun, Y. (eds.) 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, May 7-9, 2015, Conference Track Proceedings (2015).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2019).

Jain, J. et al. Oneformer: One transformer to rule universal image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2989–2998, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00292 (2023).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 4015–4026 (2023).

Zou, X. et al. Segment everything everywhere all at once. Advances in neural information processing systems 36, 19769–19782 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zheng and Sun were responsible for data labeling. Zheng and Chen designed and conducted the experiments, as well as performed the data analysis. Zheng and Chen drafted the manuscript. Zheng, Chen, Guo, and Qian reviewed the manuscript draft and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Z., Chen, Z., Sun, S. et al. A Connected Building Landscape dataset for Instance Segmentation. Sci Data 12, 1902 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06172-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06172-5