Abstract

The rate performance of any electrode or solid electrolyte material used in a battery is critically dependent on the migration barrier (Em) governing the motion of the intercalant ion, which is a difficult-to-estimate quantity both experimentally and computationally. The foundation for constructing and validating accurate machine learning (ML) models that are capable of predicting Em, and hence accelerating the discovery of novel electrodes and solid electrolytes, lies in the availability of high-quality dataset(s) containing Em. Addressing this critical requirement, we present a comprehensive dataset comprising 621 distinct literature-reported Em values calculated using density functional theory based nudged elastic band computations, across 443 compositions and 27 structural groups consisting of various compounds that have been explored as electrodes or solid electrolytes in batteries. Our dataset includes compositions corresponding to fully charged and/or discharged states of electrodes, with intermediate compositions incorporated in select instances. Crucially, for each compound, our dataset provides structural information, including the initial and final positions of the migrating ion, along with its corresponding Em in easy-to-use .xlsx and JSON formats. We envision our dataset to be highly useful for the scientific community, facilitating the development of advanced ML models that can predict Em precisely and accelerate materials discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Ionic conductivity (σ) is one of the most important properties that is used to characterize materials used for electrochemical applications, such as a battery electrode or an electrolyte1,2,3,4. Typically, ionic conduction is a thermally activated process defined by the Nernst-Einstein equation as,

where q and x are the charge and concentration of the intercalant (or the electroactive ion), respectively. D(x) is the diffusion coefficient of the intercalant that varies with x, T is the temperature and kB is the Boltzmann constant. D(x) relates the diffusive flux (J) and the concentration gradient (∇ x of the intercalating species via the Fick’s first law (J = −D(x) ∇ x)5. Further, D(x) can be written as,

DJ is the jump diffusion coefficient, which captures all the cross correlations among the individual atomic migrations and θ is the thermodynamic factor that captures the non-ideality of the solid solution (i.e., the interactions between the migrating ions and the host framework). θ is defined as \(\theta =\frac{\partial (\mu /{k}_{B}T)}{\partial lnx}\), where μ is the chemical potential of the migrating ion. In solid electrodes and electrolytes, x is typically the site fraction of the migrating ion. For an ideal solid solution where each ionic hop has an identical hop frequency that is independent of the local concentration/configuration, D(x) becomes,

g is the geometric factor that determines how the diffusion channels are connected, f is the correlation factor, a and ν, are the hop distance and vibrational prefactor, respectively, and Em is the activation energy of migration. Ion transport within a crystalline lattice occurs through ionic migration events, where an ion moves from its original or interstitial site in a lattice to a neighboring vacant site, via a transition state. The migration process is influenced by the energy landscape encountered by the ion during its movement, with the Em playing a crucial role in determining the ease of ionic mobility and, consequently, the material’s σ.

Extensive research has focused on enhancing ionic conductivity by minimizing Em, as this directly improves the rate capabilities of battery systems. Previous studies have shown the underlying host structure to play a vital role in influencing D, such as the presence of interconnected prismatic sites leading to improved Na+ mobility in P2-type layered structures6. In compositions like LiNiO2, Li off-stoichiometry leading to Ni2+ ions in the Li layers obstructing diffusion pathway can effect the Li-ion conductivity significantly7. Indeed, dopants that stabilize the layered structure, such as Ti4+ have been used to improve Na+ mobility8. In the case of phosphates, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)9,10 studies reveal that intercalant diffusivity is not governed by a single, uniform barrier but by a distribution of local energy barriers that are dictated by the arrangement of neighboring transition metal cations11. Additionally, subtle electrostatic distortions that screen electrostatic interactions between the intercalant and the anion framework have been shown to improve intercalant mobility in polyanionic structures12.

Galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT)13,14 measurements in Mn and Fe rich disordered rocksalt structures have revealed the importance of Li-exccess compositions, particle size, and the underlying redox process as some of the important factors that affect the intercalant diffusivity15,16,17. Bonnick et al. illustrated the influence of poor electronic conductivity resulting in strong electrostatic interactions within thiospinel lattices (e.g., MgZr2S4) resulting in a reduction of ionic diffusivity18. In summary, various structural and chemical modifications have been explored across different types of intercalation compounds, including layered, spinel, olivine, polyanionic, and other frameworks, to enhance ionic conductivity1,19,20,21, with some approaches using targeted machine learning (ML) techniques as well22,23,24. However, developing universal optimization strategies across a wide range of intercalation systems remains challenging due to the interplay between structure, composition, and other factors besides the lack of a robust Em dataset that spans a diverse range of materials.

In general, estimating diffusivities or Em using experimental techniques like variable temperature NMR, GITT, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)25,26, are either experimentally challenging or resource intensive. This is due to the extremely short time scales (10−12 s) or small length scales ( ~ few Å) of the elementary process of ionic hopping, influence of surface and structural chemistry of electrodes/electrolytes on the measurement, variations in sample preparation and measurement conditions resulting in differences in interfacial formation, bulk stoichiometry and defects, and specific equipment requirements (e.g., the need for inert ion-blocking electrodes in EIS). Thus, experimental NMR/GITT/EIS data documenting Em is unavailable for a wide range of materials.

Computational methodologies to estimate Em have gained prominence, since calculated Em can be used as a screening metric within high-throughput workflows before experimental validation. Computational techniques include empirical approaches such as bond valence sum (BVS27,28) analysis and nudged elastic band (NEB29,30) calculations (usually based on first principles simulations) or molecular dynamics (MD31,32,33). BVS analysis, though computationally swift, has accuracy limitations as it relies on an ionic bond model, making it more suitable for close-packed lattices with highly electronegative anions34,35. NEB calculations strive to estimate the migration barrier within a potential energy surface (PES) constructed by either density functional theory (DFT36,37) or interatomic potentials by modeling the ionic migration path using intermediate images that are connected by fictitious spring forces and subsequently relaxing the images to identify the saddle point that corresponds to the transition state. NEB calculations when performed in conjunction with DFT typically provide accurate Em. However, the DFT-NEB approach is computationally intensive for large systems (>100 atoms), and its accuracy/convergence can depend on the chosen exchange-correlation (XC) functional within DFT38. Classical MD (based on interatomic potentials) and ab-initio MD techniques can directly estimate D(x) at multiple T, thus yielding Em from Equation (3), but are computationally demanding due to the time and length scales that need to be captured39. Note that ab-initio MD calculations are generally more accurate in estimating Em or D(x) compared to classical MD due to the more accurate PES constructed by first principles.

Some strategies have been explored to reduce the computational costs and constraints, while retaining the accuracy, of both the DFT-NEB and ab-initio MD approaches. For example, the ‘pathfinder’ approach in conjunction with the ‘ApproxNEB’ scheme40 aims to reduce the computational constraints of DFT-NEB by mitigating convergence issues via selection of a ‘better’ initial migration path for calculation. However, the scheme still requires performing a full DFT-NEB calculation and is prone to the underlying constraints of the DFT-NEB approach. Another pathway is integrating ab-initio MD simulations with machine learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs), where the MLIPs can theoretically provide higher computational speeds with the accuracy comparable to DFT41. While several MLIP frameworks that are accurate remain chemistry-specific (i.e., there are high computational costs associated with training the MLIPs)42,43,44, the foundational or universal MLIPs45,46,47,48,49,50 have not been tested rigorously on D(x) or Em predictions, yet. More importantly, we need datasets of Em that are available over a wide-range of chemistries and structures to be able to test universal MLIPs in their utility in predicting Em and/or build ML models that are tailored to accurately predict Em that can be used for screening through materials.

In this work, we present a literature-based curated dataset of 621 DFT-NEB-derived Em values across various compounds that have been studied as electrodes or solid electrolytes in lithium, sodium, potassium, and multivalent ion based battery systems. Our dataset includes fully charged and discharged states of electrode materials, with intermediate (non-stoichiometric) compositions considered in 30 cases. Additionally, we provide structural information for each compound, including the initial and final positions of the migrating ion, along with its corresponding energy barrier, which can be used in the construction of ML models that require structural inputs, such as graph-based models leveraging transfer learning51. Our dataset includes a total of 275 distinct entries contributed by 99 systems exhibiting multiple migration pathways. We envision our dataset to be a powerful resource for the scientific research and industrial communities, enabling the development of robust ML models and MLIPs that can eventually accelerate materials discovery for batteries and other applications.

Methods

We conducted a thorough manual review of battery research articles published over the past two decades to compile computationally estimated Em values. To ensure consistency and reliability, we focused exclusively on DFT-NEB calculated Em values, as this method strikes a balance between accuracy and availability in the literature compared to other computational approaches. We note that the generalized gradient approximation (GGA52) is the most widely used XC functional among DFT-NEB calculations. Other functionals that are commonly used include Hubbard U53 corrected GGA (i.e., GGA+U54), local density approximation (LDA55), strongly constrained and appropriately normed (SCAN56) and its Hubbard U-corrected variant (SCAN+U57). Since GGA (and GGA+U) is computationally less intensive than SCAN/SCAN+U and gives reasonably accurate Em estimations38, GGA (or GGA+U) is the preferred choice for DFT-NEB calculations. Our dataset reflects this preference, with 88.05% of the collected Em values calculated using GGA, followed by GGA+U (7.27%), SCAN (3.07%) and LDA (1.61%). In cases where multiple XC functionals were used to calculate Em within the same or different research articles, we prioritised GGA-calculated values to maintain consistency with the majority of the dataset. Note that for structures where the GGA/GGA+U-calculated Em was not available, we included the Em value as calculated with the different XC functional. Thus, the Em barriers of non-GGA functionals have been used as is, and we have not done any re-calculation of such systems to ensure that all Em have been calculated at the same level of theory. Given that Em is primarily dependent on the local atomic environment, and temperature effects usually contribute to the pre-exponential factors in Equation (3), we do not expect entropic effects (such as configurational entropy) to play a major role in modifying Em and hence do not include any temperature effects within our dataset. Nevertheless, if the presence of additional possible configurations in a structure unlocks new migration pathways, the Em for such pathways can be calculated and the dataset be subsequently expanded.

We considered a research article for inclusion in our dataset only if it satisfied specific criteria ensuring the reliability and completeness of the reported DFT-NEB Em values, i.e., we included studies that provided a comprehensive methodology for Em calculations. Details on the methods we looked for in articles included the XC functional used, the number of intermediate images used to describe the migration pathway, and the supercell size employed in the NEB calculations. Articles that lacked the aforementioned details were excluded to maintain data consistency and accuracy. Structural information was another key criterion for selecting articles, where we only considered studies that provided explicit description of the parent structure(s), including the space group(s) and lattice parameters. In case of multiple articles reporting different Em values for a given structure, we included the paper (and the corresponding Em) with the most details on the structure and the methods. If the structural parameters were missing and could not be retrieved from related works or structural repositories, we excluded the corresponding study from the dataset. For materials exhibiting multiple migration pathways, we ensured that the reported Em were appropriately distinguished for each path via clear descriptions of the corresponding pathways. In cases where Em values were not explicitly stated in text but were presented through minimum energy pathway (MEP) plots or other visualizations, only articles with clear, well-labeled plots featuring correct units and axis scales were selected to ensure accurate digital data extraction.

Workflow

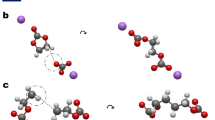

Figure 1 presents an overview of the workflow for generating the structural information for our dataset. We analyzed the collected structural information for each datapoint, and ensured that the target structures were download from either the inorganic crystal structure database (ICSD58) or the materials project (MP59). If a target structure was available in both ICSD and MP, we downloaded the computationally relaxed structure from the MP. While DFT relaxation, such as the calculations performed within MP, can change the underlying lattice parameters and ionic positions compared to an experimentally refined crystal structure, we prioritized DFT-relaxed structures so that our dataset is internally consistent with DFT-calculated Em. For all electrode materials, where possible, we downloaded the structure of the discharged composition (i.e., structures with high concentrations of intercalant ions, relevant for electrode materials) preferably over the charged composition.

If the target structure was not available in either ICSD or MP, we searched for a parent structure that shared the same space group, migrating ion concentration, and site occupancies, but containing ions that are different from the target structure in both ICSD and MP. The parent structure was then used as a template, where we substituted the occupant ions with the target ions and used the reference lattice scaling (RLS60) scheme, as implemented by the RLSVolumePredictor class in the pymatgen package61, to obtain a target structure with scaled lattice parameters and the right composition. If target structures were available but contained sites with partial occupancies, we enumerated all possible symmetrically unique configurations that satisfied the target stoichiometry of the reported structure by using the OrderDisorderStructureTransformation class in pymatgen. For all the RLS-generated and/or enumerated structures that we obtained, we performed structure relaxations with DFT to obtain the ground state (i.e., lowest energy) configuration.

For all structure relaxations with DFT, we used the GGA XC functional as available in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP, version 6.1.2)62,63. The effects of core electrons were described via projector augmented wave potentials64. We relaxed the lattice vectors, cell volume, and ionic positions of all input structures, without preserving any symmetry, until the total energy and atomic forces were below 0.01 meV and |0.03| eV/Å, respectively. We used a Γ-centred k-point mesh with a density of at least 48 k-points per Å−1 for sampling the irreducible Brillouin zone, a kinetic energy cutoff of 520 eV for describing the plane-wave basis set, and a Gaussian smearing of width 0.05 eV to intergrate the Fermi surface. For select structures that exhibited convergence difficulties with GGA, we performed the structural relaxations with GGA+U, utilizing the optimized values reported in Ref. 54 All our structures are compatible with the structure relaxation calculation settings of MP (version 2020).

Upon obtaining the ground states for all systems in our dataset, we reviewed the migration path information reported in the corresponding research articles and initialized the initial and final configurations of the migration path within each structure. Note that the initial configuration represents the migrating ion occupying the starting site while leaving the destination site vacant, while the final configuration depicts the inverse arrangement. Thus, we have assumed that all migration events for all structures considered in our dataset occur via a vacancy-based mechanism and not an interstitial-based mechanism. All the solid electrolyte materials in our dataset are stoichiometric and ordered compositions, hence we treated them as equivalent to discharged compositions of electrode materials in our workflow.

For electrode structures where the Em was reported for a charged composition (i.e., the dilute ion limit), we removed the intercalant ions from the ground state discharged structure and subsequently relaxed the structure using DFT. The initial and final configurations were then defined in this relaxed charged structure and were DFT-relaxed again to obtain their true ground state descriptions. In the case of intermediate intercalant compositions, all symmetrically distinct positional configurations corresponding to the composition were enumerated, followed by DFT relaxation to identify the ground state, and the corresponding pathway initializations were carried out in the ground state. For generating all initial and final configurations, we selected appropriate supercell sizes to ensure that the migrating ion does not experience spurious interactions by maintaining a minimum distance of at least 8 Å with its periodic images. In structures with large unit cells, such as NaSICONs (sodium superionic conductors), weberites, and oxyfluorides, we did not generate supercells to reduce computational costs.

Data Records

The dataset is available at our GitHub65 and Zenodo66 repositories, with this section describing the availability and content of the data. We report computationally calculated Em of 621 systems that have been explored as battery materials along with their structural information for each possible ionic migration event. The data can be easily downloaded in the form of a JSON file from our GitHub65 or Zenodo66 repositories.

File format

Each datapoint in the dataset is associated with specific tags that provide essential information, as summarized in Table 1. For each datapoint, we include its composition, crystal class, space group, unique system identifier, and a JSON ID that differentiates each datapoint within the database and allows easier access to different migration paths within a given structure. We assign the system name for each datapoint using a standardized format: reduced_chemical_formula + ‘_’ + path_number. For instance, MgCoSiO4 has two possible migration paths for Mg2+ diffusion, so we represent each path as MgCoSiO4_1 and MgCoSiO4_2. However, if a composition has only one active migration path, it is identified using only the reduced chemical formula. Parentheses and subscripts are omitted in the system name generation.

When multiple polymorphs of the same composition exist, the system name is modified to include the space group: reduced_chemical_formula + ‘_’ + space_group + ‘_’ + path_number. Additionally, for layered structures where both monovalent and divalent hops are considered67, we treated both hops as distinct migration paths. Charged state structures are labeled using the format: charged_state_reduced_chemical_formula + _ + intercalant, allowing clear differentiation from the discharged state configurations. In order to be compatible with the notations used in the original papers, certain prefixes, such as O3:O3-layered structure, O:olivines, M:maricite, d:δ, e:ϵ, g:γ, b:β, a:α, and a1:α1, were added to the corresponding system names to ease the identification. We did not modify our notation for intermediate compositions as compared to the discharged compositions.

The dataset provides structural information for both the initial and final configurations of each migration path in the ‘POSCAR’ format, which is compatible with pymatgen and the atomic simulation environment (ASE68) packages, enabling easy conversion into other structural representations. Each datapoint also includes a “bibtex” tag, which contains the citation details of the article from which the Em values and the migration path information were sourced. Additionally, the XC functional used to calculate the Em in the respective study is provided under the “XC” tag for reference. We acknowledge that other calculation settings, such as the potential used for describing core electrons, the mesh density and scheme used for sampling k-points in the irreducible Brillouin zone and integrating the Fermi surface, and convergence criteria employed on energies and forces, can influence the calculated Em as well, albeit to a lesser extent compared to the XC functional. To capture such DFT calculation settings in the dataset, we provide the metadata for both structural relaxations and NEB calculations, as detailed in the respective articles, in the form of a dictionary under the tag “calc_metadata”. If any specific information is not available, we populate the corresponding entry with a ‘NaN’.

Data Overview

The distribution of Em across the seven crystal systems, and the corresponding space groups within each crystal system, in our dataset is illustrated as a contour plot in Fig. 2. Each crystal system is visually distinguished using color-coded sectors in Fig. 2, with the solid concentric rings representing different Em values (in eV). Overall, our dataset includes Em values spanning 58 space groups and ranging from 0.03 eV to 8.77 eV. Out of the 621 datapoints, 528 are electrodes and 91 are electrolytes. The lowest Em (0.03 eV) corresponds to charged-LiTiO2 (P42/mnm), while the highest (8.77 eV) is observed in discharged-LiRuO2 (Pnnm), respectively. Notably, both LiTiO2 and LiRuO2 adopt the rutile-type structure and consequently exhibit the widest range of Em values in the dataset. In contrast, space groups \(Ia\overline{3}d\) and I41/acd, which contain two and three datapoints, respectively, show the narrowest range of Em values.

Contour plot illustrating the distribution of the Em dataset over different space groups from each of the seven crystal systems. Individual colored sectors represent individual crystal systems, with space groups indicated by text notations. White circles indicate invidual data points. Concentric circles correspond to different Em values (in eV), as highlighted by the blue text notations.

The space group \(Fd\overline{3}m\), corresponding to cubic spinels, has the highest number of datapoints, contributing 94 entries to the dataset. It is followed by the Pmna space group (72 datapoints), belonging to the orthorhombic system, and the P1 space group (39 datapoints) from the triclinic system. Additionally, 15 space groups contribute only a single datapoint each. Among the different crystal systems, orthorhombic accounts for the highest (205) number of datapoints, whereas hexagonal (6) contributes the least. The dataset exhibits a mean Em value of 0.848 eV with a standard deviation of 0.824 eV, indicating a highly skewed distribution. A majority (73.4%) of the Em values are below 1 eV, while 19.4% fall within the 1-2 eV range, and 7.2% exceed 2 eV. 71.4% and 23.6% of the entries are contributed by discharged (high intercalant content) and charged (low intercalant content) state structures respectively, corresponding to 106 distinct charged and discharged pairs. Intermediate intercalant compositions correspond to 5% of the dateset.

Figure 3 presents a bar chart that illustrates the number of datapoints and the range of Em values across 27 different structural groups (e.g., spinels, olivines, NaSICONs, etc.). Each bar is stacked to represent contributions from nine different intercalating ions, with the stack length indicating the number of datapoints associated with each ion. The inset pie chart provides a breakdown of the percentage contribution of each intercalating ion to the overall dataset. Additionally, the solid square and circle markers, connected by a vertical line, denote the maximum and minimum Em values observed within each structural group, thus representing the range of Em.

Illustration of the Em distribution within each of the different structural groups. The y axis on the left and right represent the number of datapoints and Em values (in eV), respectively. Stacked bar charts correspond to the counts within each structural group, with the colors indicating the split across various intercalants. The black vertical lines represent the range of Em values for a given structural group with the squares and circles representing the maxima and minima, respectively. The inset shows a pie-chart with the contributions from each intercalant (i.e., Al, Ca, K, Li, Mg, Na, Rb, Sr, and Zn, as represented by the different colors) to the total dataset.

Lithium-based intercalant compounds constitute 28.27% of the dataset, making Li the most prevalent intercalating ion, which is expected given the extensive research done on Li-based electrodes and solid electrolytes. Li is followed by calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), and magnesium (Mg) in terms of contribution. The least represented intercalants are strontium (Sr), aluminum (Al), and rubidium (Rb), with only 2, 7, and 8 datapoints, respectively. 17 out of the 27 structural groups include compounds intercalating Li, whereas Ca-based compounds are primarily found in layered structures, NaSICONs, oxides, and weberites. Na-based compounds are more widely distributed than Li, appearing in 19 of the 27 structural groups, while Mg-based compounds are predominantly found in spinel chalcogenides, layered structures, and orthosilicates. Layered structures contribute the highest number of datapoints, with 98 entries, followed by spinel chalcogenides, phosphates, and oxides. Other structural groups, such as alluaudites, Prussian blue analogs, and carbonates, are also represented but in significantly smaller numbers. The highest and lowest Em ranges among the structural groups are observed in rutiles and thiosulphates, respectively.

Technical Validation

A benchmarking of DFT-NEB Em (using different XC functionals) against experimentally reported values has been performed in our previous work38. To estimate Em, we fully relaxed the endpoint geometries representing the initial and final states of migration using DFT. Subsequently, the MEP was initialized by linearly interpolating both atomic positions and lattice vectors to create seven intermediate images between the endpoints, with a spring force constant of 5 eV/Å2 maintained between adjacent images. The images constituting the NEB were optimized along the reaction coordinate using the limited-memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (L-BFGS)69 method until the force component perpendicular to the elastic band fell below |0.05| eV/Å. The total energy of each image was also converged to within 0.01 meV. All Em values were determined assuming a vacancy-mediated mechanism in the dilute-vacancy limit.

On comparing the calculated Em against experimental values, we observed the SCAN functional to exhibit a higher accuracy on an average relative to other XC functionals. Albeit the higher accuracy of SCAN is counterbalanced by increased computational expense and potential convergence problems. Also, we found GGA to be a suitable alternative for quick and qualitative Em predictions.

Approximately 15.8% of the dataset has been calculated from scratch using the GGA or SCAN XC functional (depending on the computational feasibility for the respective system), using the above described methodology and have also been reported in other works38,70,71,72,73,74. The remaining 84.2% of the dataset has been collected from various literature sources that report DFT-NEB methodologies similar to the above description. In certain cases, articles that used fewer number of images (3 or 5) were also considered if a fully convereged MEP was reported.

Usage Notes

We present a literature-curated DFT-NEB-calculated dataset comprising 621 distinct Em values over 443 chemistries and 27 distinct structural groups, spanning a diverse set of electrode and solid electrolyte materials studied for battery applications. This dataset, which includes structural information and calculated Em values for each system, is provided in both .xlsx and JSON formats for easier and direct data extraction within our GitHub65 repository. The JSON version of the dataset is also available on Zenodo at the DoI66. The following code snippet demonstrates the conversion of structural data from the dataset into pymatgen and ASE objects for subsequent analyses. Our dataset can be effectively utilized to construct ML models for Em estimation, using either structural, compositional, or combined inputs. The snippet illustrates that the dataset can be imported directly into a pandas DataFrame, enabling its use in further machine learning model development, using libraries such as ‘scikit-learn’ and ‘pytorch’.

Conversion of JARVIS structure to pymatgen and ASE objects.

We are hopeful that the dataset will be expanded in the near future with calculated Em contributions from the scientific community. We have provided instructions on contributing to the dataset in our Zenodo repository, which will be used for maintaining version-control as well. With further expansion, the dataset can be employed to develop accurate machine learning models capable of replacing on-the-fly DFT-NEB estimations of Em, which would significantly accelerate kinetic Monte Carlo (kMC) simulations75. In turn, faster kMC simulations can bridge the gap between the high accuracy of DFT and the long timescales accessible by kMC, ultimately providing a powerful tool for quantifying ion transport dynamics. Additionally, the dataset will be suitable for fine-tuning pre-trained foundational models and for benchmarking the performance of various universal MLIPs on Em prediction tasks.

Data availability

The dataset developed as part of this work is available freely online at our GitHub (https://github.com/sai-mat-group/migration-barrier-dataset) repository and on Zenodo at the, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17240095.

Code availability

There are no specific codes or scripts developed in this work. Licenses for using the VASP code, which was employed for the DFT calculations done in this work, are available at https://vasp.at/. The pymatgen package can be downloaded freely from https://pymatgen.org/.

References

Rong, Z. et al. Materials design rules for multivalent ion mobility in intercalation structures. Chemistry of Materials 27, 6016–6021 (2015).

Euchner, H., Chang, J. H. & Gross, A. On stability and kinetics of li-rich transition metal oxides and oxyfluorides. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 8, 7956–7967 (2020).

Park, M., Zhang, X., Chung, M., Less, G. B. & Sastry, A. M. A review of conduction phenomena in li-ion batteries. Journal of power sources 195, 7904–7929 (2010).

Bachman, J. C. et al. Inorganic solid-state electrolytes for lithium batteries: mechanisms and properties governing ion conduction. Chemical reviews 116, 140–162 (2016).

Fick, A. V. on liquid diffusion. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 10, 30–39 (1855).

Clément, R. et al. Direct evidence for high na+ mobility and high voltage structural processes in p2-na x [li y ni z mn 1- y- z] o 2 (x, y, z 1) cathodes from solid-state nmr and dft calculations. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 5, 4129–4143 (2017).

Bianchini, M., Roca-Ayats, M., Hartmann, P., Brezesinski, T. & Janek, J. There and back again—the journey of linio2 as a cathode active material. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 58, 10434–10458 (2019).

Vassilaras, P. et al. Communication—o3-type layered oxide with a quaternary transition metal composition for na-ion battery cathodes: Nati0. 25fe0. 25co0. 25ni0. 25o2. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 164, A3484 (2017).

Grey, C. P. & Dupré, N. Nmr studies of cathode materials for lithium-ion rechargeable batteries. Chemical reviews 104, 4493–4512 (2004).

Verhoeven, V. et al. Lithium dynamics in limn 2 o 4 probed directly by two-dimensional 7 li nmr. Physical review letters 86, 4314 (2001).

Strobridge, F. C. et al. Characterising local environments in high energy density li-ion battery cathodes: a combined nmr and first principles study of life x co 1- x po 4. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2, 11948–11957 (2014).

Bianchini, M. et al. Na3v2 (po4) 2f3 revisited: a high-resolution diffraction study. Chemistry of Materials 26, 4238–4247 (2014).

Kang, S. D. & Chueh, W. C. Galvanostatic intermittent titration technique reinvented: Part i. a critical review. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 168, 120504 (2021).

Tang, K., Yu, X., Sun, J., Li, H. & Huang, X. Kinetic analysis on lifepo4 thin films by cv, gitt, and eis. Electrochimica Acta 56, 4869–4875 (2011).

Lee, J. et al. A new class of high capacity cation-disordered oxides for rechargeable lithium batteries: Li–ni–ti–mo oxides. Energy & Environmental Science 8, 3255–3265 (2015).

Lee, J. et al. Determining the criticality of li-excess for disordered-rocksalt li-ion battery cathodes. Advanced Energy Materials 11, 2100204 (2021).

Fong, R. et al. Redox engineering of fe-rich disordered rock-salt li-ion cathode materials. Advanced Energy Materials 14, 2400402 (2024).

Bonnick, P. et al. Insights into mg2+ intercalation in a zero-strain material: thiospinel mg x zr2s4. Chemistry of Materials 30, 4683–4693 (2018).

Lu, W., Wang, J., Sai Gautam, G. & Canepa, P. Searching ternary oxides and chalcogenides as positive electrodes for calcium batteries. Chemistry of Materials 33, 5809–5821 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Design principles for solid-state lithium superionic conductors. Nature materials 14, 1026–1031 (2015).

Canepa, P. et al. High magnesium mobility in ternary spinel chalcogenides. Nature communications 8, 1759 (2017).

Jalem, R., Nakayama, M. & Kasuga, T. An efficient rule-based screening approach for discovering fast lithium ion conductors using density functional theory and artificial neural networks. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2, 720–734 (2014).

Jalem, R. et al. Bayesian-driven first-principles calculations for accelerating exploration of fast ion conductors for rechargeable battery application. Scientific reports 8, 5845 (2018).

Sendek, A. D. et al. Holistic computational structure screening of more than 12000 candidates for solid lithium-ion conductor materials. Energy & Environmental Science 10, 306–320 (2017).

Barsukov, Y. et al. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Characterization of materials 2, 898–913 (2012).

Itagaki, M. et al. Licoo2 electrode/electrolyte interface of li-ion rechargeable batteries investigated by in situ electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Journal of Power Sources 148, 78–84 (2005).

Adams, S. From bond valence maps to energy landscapes for mobile ions in ion-conducting solids. Solid State Ionics 177, 1625–1630 (2006).

Brown, I. D. Recent developments in the methods and applications of the bond valence model. Chemical reviews 109, 6858–6919 (2009).

Jónsson, H., Mills, G. & Jacobsen, K. W. Nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths of transitions. In Classical and quantum dynamics in condensed phase simulations, 385–404 (World Scientific, 1998).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. The Journal of chemical physics 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Frenkel, D. & Smit, B. Understanding molecular simulation. Academic Press, San Diego, 2, 2–5 (2002).

Mo, Y., Ong, S. P. & Ceder, G. First principles study of the li10gep2s12 lithium super ionic conductor material. Chemistry of Materials 24, 15–17 (2012).

Car, R. & Parrinello, M. Unified approach for molecular dynamics and density-functional theory. Physical review letters 55, 2471 (1985).

Meutzner, F. et al. Computational analysis and identification of battery materials. Physical Sciences Reviews 4, 20180044 (2019).

Nestler, T., Fedotov, S., Leisegang, T. & Meyer, D. C. Towards al3+ mobility in crystalline solids: critical review and analysis. Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences 44, 298–323 (2019).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Physical review 136, B864 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Physical review 140, A1133 (1965).

Devi, R., Singh, B., Canepa, P. & Sai Gautam, G. Effect of exchange-correlation functionals on the estimation of migration barriers in battery materials. npj Computational Materials 8, 160 (2022).

He, X., Zhu, Y., Epstein, A. & Mo, Y. Statistical variances of diffusional properties from ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. npj Computational Materials 4, 18 (2018).

Rong, Z., Kitchaev, D., Canepa, P., Huang, W. & Ceder, G. An efficient algorithm for finding the minimum energy path for cation migration in ionic materials. The Journal of chemical physics 145 (2016).

Deringer, V. L., Caro, M. A. & Csányi, G. Machine learning interatomic potentials as emerging tools for materials science. Advanced Materials 31, 1902765 (2019).

Choyal, V., Sagar, N. & Sai Gautam, G. Constructing and evaluating machine-learned interatomic potentials for li-based disordered rocksalts. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 20, 4844–4856 (2024).

Gartner III, T. E. et al. Signatures of a liquid–liquid transition in an ab initio deep neural network model for water. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 26040–26046 (2020).

Achar, S. K., Zhang, L. & Johnson, J. K. Efficiently trained deep learning potential for graphane. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 125, 14874–14882 (2021).

Batatia, I. et al. The design space of E(3)-equivariant atom-centred interatomic potentials. Nat Mach Intell 7, 56–67, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-024-00956-x (2025).

Batatia, I. et al. A foundation model for atomistic materials chemistry. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.00096 (2023).

Rhodes, B. et al. Orb-v3: atomistic simulation at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.06231 (2025).

Deng, B. et al. Chgnet as a pretrained universal neural network potential for charge-informed atomistic modelling. Nature Machine Intelligence 5, 1031–1041 (2023).

Chen, C. & Ong, S. P. A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nature Computational Science 2, 718–728 (2022).

Kim, J. et al. Data-efficient multifidelity training for high-fidelity machine learning interatomic potentials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 1042–1054, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c14455 (2024).

Devi, R., Butler, K. T. & Sai Gautam, G. Optimal pre-train/fine-tune strategies for accurate material property predictions. npj Computational Materials 10, 300 (2024).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Physical review letters 77, 3865 (1996).

Anisimov, V. I., Zaanen, J. & Andersen, O. K. Band theory and mott insulators: Hubbard u instead of stoner i. Physical Review B 44, 943 (1991).

Wang, L., Maxisch, T. & Ceder, G. Oxidation energies of transition metal oxides within the GGA+ \emphU framework 73, 195107. Publisher: APS.

Jones, R. O. & Gunnarsson, O. The density functional formalism, its applications and prospects. Reviews of Modern Physics 61, 689 (1989).

Sun, J., Ruzsinszky, A. & Perdew, J. P. Strongly constrained and appropriately normed semilocal density functional. Physical review letters 115, 036402 (2015).

Sai Gautam, G. & Carter, E. A. Evaluating transition metal oxides within dft-scan and scan+ u frameworks for solar thermochemical applications. Physical Review Materials 2, 095401 (2018).

Hellenbrandt, M. The inorganic crystal structure database (icsd)—present and future. Crystallography Reviews 10, 17–22 (2004).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The materials project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL materials 1 (2013).

Chu, I.-H., Roychowdhury, S., Han, D., Jain, A. & Ong, S. P. Predicting the volumes of crystals. Computational Materials Science 146, 184–192 (2018).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python materials genomics (pymatgen): A robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Computational Materials Science 68, 314–319 (2013).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Physical Review B 48, 13115 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Physical review B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Physical review b 59, 1758 (1999).

Devi, R., Balasubramanian, A., Butler, K. T. & Gopalakrishnan, S. G. Migration barrier dataset. https://github.com/sai-mat-group/migration-barrier-dataset (2025).

Devi, R., Balasubramanian, A., Butler, K. T. & Sai Gautam, G. Dft-neb-migration-barrier-dataset v1.0 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17240095 (2025).

Van der Ven, A., Ceder, G., Asta, M. & Tepesch, P. First-principles theory of ionic diffusion with nondilute carriers. Physical Review B 64, 184307 (2001).

Larsen, A. H. et al. The atomic simulation environment—a python library for working with atoms. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 29, 273002 (2017).

Nocedal, J. Updating quasi-newton matrices with limited storage. Mathematics of computation 35, 773–782 (1980).

Tekliye, D. B. et al. Exploration of nasicon frameworks as calcium-ion battery electrodes. Chemistry of Materials 34, 10133–10143 (2022).

Tekliye, D. B. & Gautam, G. S. Fluoride frameworks as potential calcium battery cathodes. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 12, 18993–19007 (2024).

Deb, D. & Sai Gautam, G. Exploration of oxyfluoride frameworks as na-ion cathodes. Chemistry of Materials 36, 11892–11904 (2024).

Gautam, G. S. et al. First-principles evaluation of multi-valent cation insertion into orthorhombic v 2 o 5. Chemical Communications 51, 13619–13622 (2015).

Gautam, G. S., Sun, X., Duffort, V., Nazar, L. F. & Ceder, G. Impact of intermediate sites on bulk diffusion barriers: Mg intercalation in mg 2 mo 3 o 8. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 4, 17643–17648 (2016).

Wang, Z. et al. Kinetic monte carlo simulations of sodium ion transport in nasicon electrodes. ACS Materials Letters 5, 2499–2507 (2023).

Acknowledgements

G.S.G. and K.T.B. would like to acknowledge financial support from the Royal Society under grant number IES\R3\223036, and the United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI) Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), under projects EP/Y000552/1 and EP/Y014405/1. G.S.G. acknowledges financial support from the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB) of the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, under sanction number IPA/2021/000007. R.D. thanks the Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India, for financial assistance. R.D. and G.S.G. acknowledge the computational resources provided by the Supercomputer Education and Research Centre, IISc, for enabling some of the calculations showcased in this work. We acknowledge National Supercomputing Mission (NSM) for providing computing resources of ‘Param Utkarsh’ at CDAC Knowledge Park, Bengaluru. PARAM Utkarsh is implemented by CDAC and supported by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) and Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India. Via our membership of the UK’s HEC Materials Chemistry Consortium, which is funded by EPSRC (EP/X035859/1), this work used the ARCHER2 UK National Supercomputing Service (http://www.archer2.ac.uk).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Devi, R., Balasubramanian, A., Butler, K.T. et al. A literature-derived dataset of migration barriers for quantifying ionic transport in battery materials. Sci Data 12, 1922 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06196-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06196-x