Abstract

Magnolia zenii (Magnoliaceae) is an extremely endangered tree species endemic to eastern China, has only 115 individuals remaining in the wild. By integrating PacBio HiFi (49×), Oxford Nanopore (ONT; 101×) long-read sequencing, and Hi-C chromatin interaction data, we achieved a high-quality chromosome-level genome with scaffold N50 of 86 Mb, covering 99.97% of the estimated genome size. The genome annotation predicted 74,782 protein-coding genes and revealed a repetitive sequence content of 72.87%, dominated by long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons (53.59%). The mitochondrial (915,126 bp) and chloroplast (160,079 bp) genomes were fully characterized. BUSCO analysis confirmed 99.4% genome completeness and 98.4% gene annotation completeness. This genomic resource provides a foundation for studying the genetic mechanisms underlying its endangered status and future horticultural.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Magnolia zenii W. C. Cheng, a Tertiary relict specie, persists as a critically endangered (CR)1 plant with only 115 mature individuals2 remaining in fragmented distribution across Baohua Mountain of Jiangsu Province, eastern China, as documented in the China Species Red List1. This species is valued in horticulture because of its elegant pale blossoms and stately upright trunk3 (Fig. 1a). Despite its ecological importance, while previous research have mainly concentrated on chloroplast genome sequencing for phylogenetic analyses and only a limited number of microsatellite markers developed for population genetic diversity analyses4,5, the absence of whole-genome investigations hinders comprehensive understanding of its reproductive limitations6, genetic bottlenecks, and adaptive mechanisms. Magnoliaceae is one of the oldest extant angiosperm families, yet genomic studies on this family have been relatively limited. Globally and within China, nearly 50% of Magnoliaceae species are threatened7,8. Despite recent advancements, only eight species (Liriodendron chinense (Hemsley) Sargent, Magnolia biondii Pamp., M. kwangsiensis Figlar & Noot., M. hypoleuca Sieb. & Zucc, M. officinalis Rehd., M. sieboldii K. Koch, M. sinica (Law) Noot., Michelia alba DC) have been subjected to in-depth genomic analysis in the past five years9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. This limited genomic resource significantly hinders both the understanding of the endangered mechanisms of Magnoliaceae species and their evolutionary relationships.

The floral characteristics (a) and genomic features of M. zenii (b). From outer to inner layers (excluding the outermost chromosome coordinates): Class I TE density, Class II TE density, protein-coding gene density, tandem repeat proportion, GC content, and collinearity blocks (minimum length of 100 kb). Window size: 500 kb.

Whole-genome sequencing would enable systematic identification of key reproductive development genes and functional variations, while elucidating the molecular basis of pollen and embryo sac abortion6. Furthermore, it would facilitate assessment of population genetic diversity and genomic architecture, providing critical genetic insights for conservation strategies such as artificial propagation (e.g., seedling transplantation), population restoration optimization, and stress resistance improvement. Particularly crucial given current population decline and ecological competition pressures17, genomic data integration with population dynamics and niche analysis may help to inform precision conservation measures. This integrated approach would enhance the species’ long-term survival prospects and support sustainable utilization efforts.

Here, we combined PacBio HiFi, ONT ultra-long reads, and Hi-C interaction maps to generate a haplotype-resolved chromosome-level assembly and performed robust gene annotation with ONT transcriptomic data. This approach addresses challenges in resolving complex regions and ensures high contiguity and annotation accuracy. The assembly spans 3.6 Gb with a scaffold N50 of 86 Mb and 7 gaps (Table 1), achieving near telomere-to-telomore resolution. Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO18, v. 5.3.2) assessment confirmed 99.4% genome completeness and 98.4% gene annotation completeness, with 74,782 protein-coding genes identified. Repetitive elements (72.87%) were dominated by LTR retrotransposons (53.59%). The mitochondrial (915,126 bp) and chloroplast (160,079 bp) genomes were also fully characterized. The assembly provides a foundational resource for investigating its genomic basis of endangerment, identifying key genomic variants for breeding, and reconstructing evolutionary history. It also advances horticultural trait research by enabling precise genetic and genomic analysis of M. zenii.

Methods

Sample preparation and DNA/RNA extraction

Sampled fresh flowers and leaves from a mature M. zenii indivadual in Baohua Mountain, Jiangsu, China. Flowers and leaves were preserved in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°. DNA was extracted from leaves using a modified CTAB methods19. Total RNA was extracted from flowers and leaves using the R6827 Plant RNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, the concentration of the extracted DNA and RNA samples was determined using the NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) and the Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), while their integrity was assessed via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Library construction and sequencing

DNA integrity was assessed using the Femto Pulse system. Genomic DNA (8 μg) was fragmented using the Megaruptor 3, followed by purification with AMPure PB magnetic beads. SMRT bell libraries were constructed using the Pacific Biosciences SMRT Bell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0. Libraries were size-selected on the BluePippin™ system to target 15 kb insert sizes, followed by primer annealing and binding of SMRT bell templates to polymerases using a DNA/polymerase binding kit. The sequencing was performed on the PacBio Sequel II/IIe platform at Benagen Genomics. This yielded 88 Gb (49×) of HiFi data with N50 of 17 kb.

ONT library construction and sequencing

A 2.5 μg aliquot of quality-checked genomic DNA was purified with 1 × magnetic beads. A 1 μL sample was quantified via Qubit fluorometry. DNA underwent end repair and damage remediation, followed by 1 × magnetic bead purification. DNA was eluted with 61 μL EB buffer, and a 1 μL aliquot was re-quantified. Adapter ligation was performed, followed by 0.4 × magnetic bead purification. Elution was conducted with 25 μL Elution Buffer (SQK-LSK110), and a final 1 μL sample was quantified. Libraries were loaded onto R9.4 sequencing chips and sequenced on the PromethION sequencer (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) for 48–72 hours. This generated 182 Gb (101×) of data with an N50 of 60 kb.

Hi-C library construction and sequencing

Input Hi-C DNA was fragmented, followed by end blunting. 5′ ends were phosphorylated, and 3′ dA tails were added. Adapters were ligated to fragmented DNA ends. Streptavidin magnetic beads were used to capture biotin-labeled regions. Captured Hi-C DNA underwent PCR amplification, followed by quantification and quality control. Libraries were circularized and validated. Qualified libraries were sequenced on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform using paired-end sequencing protocols.

ONT transcriptome sequencing

A 500 ng aliquot of quality-checked total RNA was diluted to 9 μL with nuclease-free water. Reverse transcription primers were ligated, followed by cDNA synthesis and amplification. Libraries were purified using AMPure beads and adapter ligated. Final libraries were loaded onto R9.4 sequencing chips and sequenced on the PromethION sequencer (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) for 48–72 hours. This produced 18 Gb of transcriptome data. This produced 18 Gb of transcriptome data.

Chromosome-level genome assembly

Quality filtering of second-generation Hi-C data was performed using the fastp20 (v. 0.21.0) software, including adapter trimming, removal of low-quality regions, and discarding of short reads. PacBio HiFi reads were initially assembled using Hifiasm21 (v. 0.19.8-r602) to generate a draft genome. Hi-C reads were then aligned to this draft genome using Juicer22 (v. 0.6.14), followed by preliminary Hi-C-assisted chromosome scaffolding with 3D-DNA23 (v. 180922). Subsequent manual validation and iterative refinement were performed in Juicebox24 (v. 3.1.4), focusing on optimizing chromosomal partition boundaries, correcting structural misassembles, and resolving switch errors. Each chromosome was then individually re-scaffolded using 3D-DNA to enhance contiguity, with further manual adjustments in Juicebox to remove spurious insertions, correct orientation discrepancies, and address other detectable errors. Following rigorous manual curation, the final assembly comprised a chromosome-scale framework and dispersed sequences, with gaps fixed to 100 bp. Statistical details are provided in Table S1-4.

To further refine the assembly, gaps were closed using HiFi reads with the QuarTeT25 (v. 1.1.3) software, and telomeric extensions were implemented. Chromosome termini with incomplete (TTTAGGG)n repeats were extended by re-aligning HiFi reads to the assembly using Minimap226 (v. 2.24-r1122). Telomeric regions were reassembled into contigs and integrated into the final scaffolds to achieve near-telomere-to-telomere continuity. Given the incomplete assembly of chloroplast (160 Kbp) and mitochondrial (915 Kbp) genomes generated by Hifiasm, we employed OATK27 (v. 0.9) to independently assemble these organelle genomes using HiFi reads.

Redundancy and contamination filtering

Isolated contigs were aligned to chromosome, mitochondrial, and chloroplast sequences using Redundans28 (v. 0.13c). This workflow identified redundant fragments (e.g., haplotigs) and high-copy regions (e.g., rDNA arrays) prone to fragmentation in Hifiasm assemblies. Contigs with a typical low coverage or rDNA signatures were identified and flagged, followed by manual validation and systematic removal of suspected redundancies and contaminants in a consolidated workflow. In addition, the chromosome number (2n = 38) was determined based on the results of karyotype analysis. Finally, we generated a high-quality, haplotype-phased gapless genome of M. zenii (Fig. 1b).

Collinearity and synteny

Collinear analysis between the M. zenii assembly and reference genomes (Pachylarnax sinica (M. W. Law) N. H. Xia & C. M. Wu) using Minimap2 confirmed consistent chromosome ordering (Fig. 2).

Identification of chromosomal landmarks

Key genomic features were mapped onto chromosomes. Telomere repeats: The telomeric motif (TTTAGGG) was identified at termini of most chromosomes. Centromeric tandem repeat: A highly repetitive centromeric-like sequence (CCAACGGAGATGCTCATAACTCCCTCGTTTGATGTCGGATTGGGTCGATTTTTGGTCATCTGAAAGGTACTTTAATGCTCTTTCATTCCTGATTGGAATCGTGGTATTCCGAGACCATTTGGGCATCCGTAAGTGGGATCGCAGTCGTCGGTCCTGAATTTTTCCTTCATCTCCTTGTCCAATAGTAACCTTCATAACTCTCTCTTCAGTGGTCGAATTTAGACTATTTTGAGCTCATTGGAATGGTAACTCGACAAGCTTCCAAATGGGACCAGAATTGTCTAATTCTGAGACCGTTCGATATCCCAAAAGCCCGTTGGAACTCTTCGATCGTCATTTTGCAATTTGGATTGTTAATCTTTCCAAATCGCGCGA) was detected across multiple chromosomes, consistent with centromeric regions. rDNA arrays: The 18-5.8-28S rDNA cluster was distributed across multiple chromosomes, as were 5S rDNA arrays (Supplementary Figure S1).

Annotation

Repetitive element characterization

Repetitive elements were identified using the EDTA29 (v. 2.2.0; parameters: --sensitive 1--anno 1) pipeline to generate a transposable element (TE) library and annotate repetitive regions in the genome. In total, 5,100,109 repetitive sequences were identified, spanning 2.62 Gb and accounting for 72.87% of the genome. Among these, LTR retrotransposons were the most abundant class, representing 2,588,781 elements and 1.93 Gb, or 53.59% of the repetitive content (Table S5).

Gene annotation

A multi-evidence strategy was employed for gene annotation. Homology-based evidence was generated using non-redundant protein sequences from 14 related species (M. biondii Pampan., M. sinica (Y. W. Law) Noot., Liriodendron chinense (Hemsl.) Sargent., Chimonanthus salicifolius H. H. Hu, Aristolochia fimbriata Cham., Annona glabra Linn., Piper nigrum Linn., Saururus chinensis (Lour.) Baill., Warburgia ugandensis Sprague, Cinnamomum kanehirae (Hayata) K.F.Chung & C.L.Hsieh, Acorus tatarinowii Schott, Amborella trichopoda Baill., Tetracentron sinense Oliv., Ceratophyllum demersum L.) in an aggregated database (398,887 sequences). For transcriptome evidence, ONT long-reads were mapped with Minimap2 and assembled into transcripts via StringTie30 (v. 1.3.5), assembly statistics are presented in Table 2.

Transcriptome assembly results were first annotated using the PASApipeline31 (v. 2.5.3) to define gene structures, followed by alignment to the reference protein dataset of 398,887 non-redundant sequences. Full-length genes were identified through this alignment, and their sequences were used to train both AUGUSTUS32 (v. 3.5.0) and SNAP33, with five rounds of iterative optimization.

The MAKER234 (v. 2.31.9) annotation workflow was then applied, integrating ab initio predictions (via AUGUSTUS and SNAP), transcript evidence, and homologous protein evidence. Key steps included: (1) masking repetitive regions with RepeatMasker; (2) de novo gene prediction using AUGUSTUS and SNAP; (3) aligning transcript sequences to the genome via BLASTN and protein sequences via BLASTX; (4) refining alignments with Exonerate35 (v. 2.2.0); and (5) generating hints files to guide the integration of gene models by AUGUSTUS and SNAP.

To address the lower precision of MAKER process annotations36, EVidenceModeler37 (EVM, v. 2.0.0) was employed to consolidate MAKER and PASA results into a unified gene set. TE protein domains identified by TESorter38 (v. 1.4.6) were masked during EVM integration to exclude transposable element (TE) coding regions. PASA was further applied to refine EVM annotations by incorporating untranslated regions (UTRs) and alternative splicing events. Final annotations were filtered to exclude genes with disrupted coding frames (e.g., internal stop codons, ambiguous bases, or missing start/stop codons) or lengths less than 50 amino acids. NcRNA annotation was performed with tRNAScan-SE39 (v. 2.0.12) for tRNAs, barrnap (https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap) for rRNAs, and RfamScan for other ncRNAs, ensuring comprehensive functional characterization.

Integrated annotation and functional characterization

Protein-coding genes were named systematically using a species-specific nomenclature (e.g., Yuzen01aG0000100), while non-coding RNAs were annotated separately.

Functional annotation combined homology-based approaches

The functional annotation of protein-coding genes was conducted using three strategies. Gene functions were annotated by aligning against the EggNOG-Mapper40 homologous gene database, incorporating functional information such as Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). Protein sequences were aligned against protein databases (Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL, NCBI NR, and Arabidopsis) using DIAMOND41 (v. 2.4.0; parameters: Identity ≥30%, E-value < 1e-5) to identify the best hit for each gene. Finally, the sequence was aligned with the sub databases in InterPro (PRIMTS, Pfam, SMART, PANTHER, and CDD) using InterProScan42 (v. 5.14-53.0) to identify the conserved domains and motifs. Ultimately, 15,883 genes (21.24%) remained unannotated. Full annotation statistics are provided in Table S6.

Data Record

All data associated with this study have been deposited in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC)43,44, Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences/China National Center for Bioinformation, under the BioProject (accession number PRJCA037928) and the BioSample (accession number SAMC5173072), accessible via https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/. The raw sequencing data (Hi-C reads, ONT reads, PacBio HiFi reads and Iso-Seq ONT reads) have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) in NGDC under the accession number CRR187751845, CRR187752046, CRR187752147 and CRR187751948, respectively. The complete genome assembly and annotation have been submitted in the Genome Warehouse (GWH) in NGDC under the accession number GWHGEBD00000000.149. The sequencing data have been also deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with accession number SRR3387190150, SRR3387190251, SRR3387190352 and SRR3387190453 under BioProject accession number PRJNA1273192. The two haplotypes of the final assembled genome have also been submitted to GenBank, with assembly accession numbers GCA_052055185.154 and GCA_052055145.155.

Technical Validation

Assessment of the genome assembly

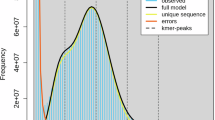

The final genome assembly spans 3.6 Gb, containing two complete haplotypes consistent with the k-mer based size estimation. The assembly achieved 85 Mb contig N50 and 7 gaps, demonstrating high continuity (Table 1). To evaluate coverage, HiFi reads were mapped using BWA56 (v. 0.7.17-r1188), while transcriptomic ONT reads were mapped to the genome using Minimap2. Non-primary alignments were filtered out, both HiFi reads and Iso-seq demonstrated very high mapping rates of 99.14% and 95.29%, respectively. This indicates that our sequencing data provides relatively high coverage of the genome. Redundancy was assessed by remapping sequencing data to the assembled genome (filtered for non-primary alignments). In redundant regions, coverage depths were approximately half of the expected values due to allelic phasing. The absence of prominent peaks preceding the main coverage peak (determined by genome size estimation) indicated no significant redundancy (Fig. 3a). Similarly, BUSCO analysis of single-copy and multi-copy core genes showed uniform coverage distributions with no overlapping peaks (Fig. 3b). GC content distribution across HiFi sequencing data at varying coverage depths showed no detectable bias (Fig. 4), ensuring even representation of genomic regions. Remapping Hi-C data to the final assembly using BWA demonstrated strong chromosome clustering (Fig. 5), with no evident misassemble artifacts.

Assessment of the gene annotation

The genome was evaluated using BUSCO, revealing that 99.4% of core genes were complete (including both single-copy and duplicated genes), with only 0.3% missing, indicating a high level of genome completeness. For the transcriptome data integrated with annotated proteins, BUSCO analysis showed that 98.4% of core genes were complete. Additionally, 0.4% were fragmented (F) and 1.2% were missing (M), with a total of 1,614 BUSCOs assessed.

Data availability

All raw data from this study are publicly accessible via NGDC (https://download.cncb.ac.cn/gsa5/CRA026213) and NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1273192). The complete genome assembly and annotation results are also available through both platforms (NGDC: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/98046/show; NCBI: http://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_052055185.1 and http://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_052055145.1).

Code availability

All data processing procedures were performed following the protocols and manuals of the bioinformatics software, without employing any custom codes or scripts in this study. Detailed parameters are thoroughly documented in the Methods section.

References

Wang, S., Xie, Y. China species red list (Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2004).

Li, N. et al. Analyses on population structure and dynamic characteristics of Yulania zenii in Baohua Mountain of Jiangsu Province. Journal of Plant Resources and Environmrnt 33, 98–105 (2024).

Wang, P. et al. Classification and ordination of a Magnolia zenii community based on a self-organizing feature map. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University 36, 255–263 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. The complete plastid genome of Magnolid zenii and genetic comparison to Magnoliaceae species. Molecules 24, 261 (2019).

Chen, Y. & Nan, C. ISSR analysis on genetic diversity of endangered plant Magnolia zenii. Journal of Sichuan Agricultural University 34, 445–449 (2016).

Wang, S., Shen, Y., Bao, H. & He, H. Change of anatomical structure in the process of mega- and microsporogenesis and female and male gametophyte development of Yulania zenii. Journal of Plant Resources and Environment 30, 46–53 (2021).

Rivers, M. et al. The Red List of Magnoliaceae—Revised and Extended (Richmond, VA: Botanic Gardens Conservation International, 2016).

Qin, H. et al. Threatened species list of China’s higher plants. Biodiv Sci 2017 25, 696–744 (2017).

Chen, J. et al. Liriodendron genome sheds light on angiosperm phylogeny and species-pair differentiation. Nat. Plants 5, 18–25 (2019).

Doing, S. et al. The genome of Magnolia biondii Pamp. provides insights into the evolution of Magnoliales and biosynthesis of terpenoids. Hortic. Res. 8, 38 (2021).

Shi, C. et al. A high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly of the endangered tree Kmeria septentrionalis. Sci. Data 11, 775 (2024).

Zhou, L. et al. The genome of Magnolia hypoleuca provides a new insight into cold tolerance and the evolutionary position of magnoliids. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1108701 (2023).

Yin, M. et al. The chromosome-scale genome of Magnolia officinalis provides insight into the evolutionary position of magnoliids. iScience 24, 102997 (2021).

Lu, X. et al. The Chromosome-Scale Genome of Magnolia sieboldii K. Koch Provides Insight Into the Evolutionary Position of Magnoliids and Seed Germination. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 25, e14030 (2025).

Cai, L. et al. The chromosome-scale genome of Magnolia sinica (Magnoliaceae) provides insights into the conservation of plant species with extremely small populations (PSESP). GigaScience 13, giad110 (2024).

Jiang, S. et al. A high-quality haplotype genome of Michelia alba DC reveals diferences in methylation patterns and fower characteristics. Mol. Hortic. 4, 23 (2024).

Jiang, G., Zhang, G., Zhang, G. & Wang, J. Intra- and interspecific competition of endangered plant Magnolia zenii. Chinese Journal of Ecology 29, 201–206 (2010).

Simão, F. A. et al. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212. ytochem Bull. 19, 11–15 (1987) (2015).

Doyle, J. & Doyle, J. L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull. 19, 11–15 (1987).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Cheng, H. et al. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Sci. 356, 92–95 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016).

Lin, Y. et al. quarTeT: a telomere-to-telomere toolkit for gap-free genome assembly and centromeric repeat identification. Hortic. Res. 10, uhad127 (2023).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Zhou, C. et al. Oatk: a de novo assembly tool for complex plant organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 26, 235 (2025).

Pryszcz, L. P. & Gabaldón, T. Redundans: an assembly pipeline for highly heterozygous genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e113 (2016).

Ou, S. et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol. 20, 275 (2019).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295 (2015).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–5666 (2003).

Stanke, M., Diekhans, M., Baertsch, R. & Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24, 637–644 (2008).

Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5, 59 (2004).

Cantarel, B. L. et al. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 18, 188–196 (2008).

Ewan, B. & Guy, S. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 6, 31 (2005).

Cook, D. E. et al. Long Read Annotation: automated eukaryotic genome annotation based on long-read cDNA sequencing. Plant Physiol. 179, 38–54 (2019).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 9, R7 (2008).

Zhang, R. et al. TEsorter: an accurate and fast method to classify LTR-retrotransposons in plant genomes. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac17 (2022).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964 (1997).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through orthology assignment by eggNOG-Mapper. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 2115–2122 (2017).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240 (2014).

Chen, M. et al. Genome Warehouse: a public repository housing genome-scale data. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 19, 584–589 (2021).

Database Resources of the National Genomics Data Center. China National Center for Bioinformation in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D27–D38 (2022).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA026213/CRR1877518 (2025).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA026213/CRR1877520 (2025).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA026213/CRR1877521 (2025).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA026213/CRR1877519 (2025).

NGDC Genome Warehouse https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/98046/show (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive http://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRX29084017 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive http://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRX29084016 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive http://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRX29084015 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive http://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRX29084014 (2025).

NCBI Assembly http://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_052055185.1 (2025).

NCBI Assembly http://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_052055145.1 (2025).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Scientific Fund of Nanjing Botanical Garden Men. Sun Yat-Sen (Grant No. JSPKLB202506).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.W. conceived and designed the study. N.L. was responsible for sample collection and preparation and performed bioinformatics analysis. S.Y. collected the samples. B.W. drafted the manuscript, while N.L., Z.Z., S.Y. and D.Y. revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Nw., Zhang, Zn., Yuan, S. et al. Near telomere-to-telomere (T2T) level genome assembly of the critically endangered plant Magnolia zenii (Magnoliaceae). Sci Data 12, 1928 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06208-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06208-w