Abstract

The EUNIS habitat classification is crucial for categorising European habitats, supporting European policy on nature conservation and implementing the Nature Restoration Law. To meet the growing demand for detailed and accurate habitat information, we provide spatial predictions across Europe (EEA39 territory) for 260 EUNIS habitat types at hierarchical level 3, together with independent validation and uncertainty analyses. Using ensemble machine learning models, together with high-resolution satellite imagery and ecologically meaningful climatic, topographic and edaphic variables, we produced a European habitat map indicating the most probable habitat overall at 100-m resolution across Europe. Additionally, we provide information on prediction uncertainty and the most probable habitats at level 3 within each EUNIS level 1 formation. This product is particularly useful for both conservation and restoration purposes. Predictions were cross-validated at European scale using a spatial block cross-validation and evaluated against independent data from France (forests only), the Netherlands and Austria. The maps achieved strong predictive performance, with F1-scores ranging from 0.61 to 0.94 in spatial cross-validation and from 0.33 to 0.95 in external validation datasets with distinct trade-offs in terms of recall and precision across habitat formations. Accuracy improved for rare or localized habitats when considering the top 3 predicted classes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The European continent is rich in natural and semi-natural habitats that host diverse species of flora and fauna and provide a wide range of ecosystem services. However, these habitats are under major pressure due to climate change, pollution, biological invasions, rapid urbanisation, agricultural expansion, as well as intensification in some areas and abandonment in others, which threaten the extent and quality of these habitats. The European Environmental Agency (EEA)‘s latest assessment1 on the State of Nature in Europe reveals an alarming decline in Europe’s biodiversity, with most protected species and habitats lacking adequate conservation.

Despite these challenges, habitat assessments are largely based on expert judgment rather than field data1, leading to uncertainties in evaluating their true conservation status. Additionally, the exact extent of habitats remains unknown, particularly outside protected areas (e.g. in the context of the EU Habitats Directive assessment within and outside Natura 2000 sites), posing additional challenges to biodiversity conservation.

To monitor these pressing environmental pressures effectively, it is imperative to acquire accurate and comprehensive knowledge of the distribution of habitats at high spatial and thematic resolutions across Europe.

In Europe, the European Nature Information System (EUNIS)2,3,4,5 is the habitat classification framework designed for a comprehensive coverage of habitat types across the continent. EUNIS is particularly suited for large-scale mapping, including remote sensing-based “wall-to-wall” approaches. This also distinguishes it from widely used maps of Potential Natural Vegetation6,7, which represent theoretical landscapes not affected by humans rather than current habitat distributions8. EUNIS Habitat Classification is a hierarchical system with multiple nested levels, each offering increasing levels of detail and specificity in describing habitat types4. The classification system allows users to navigate from broader habitat categories to more specific habitat types (from level 1 to level 6). Level 1 distinguishes the major habitat formations such as wetlands, grasslands, forests, etc. To align with the most recent consistently revised classification9,10, this study focuses on Level 3 which provides detailed descriptions for terrestrial habitats and has consistent coverage across Europe.

Producing habitat maps requires accurate in-situ data covering a diverse set of habitats in Europe11. The compilation of the European Vegetation Archive12 (EVA) and advances in classification expert systems4,13 have enabled large-scale classification of European habitats using in-situ vegetation data. These systems assign individual vegetation plots to established classification frameworks such as EUNIS, providing ground truth data for habitat modelling and mapping at large scales. However, while in-situ data provide valuable reference points, they are often spatially limited and time-consuming to collect.

Remote sensing offers a complementary approach by enabling large-scale, high-resolution habitat mapping across extensive areas, including inaccessible sites. In addition to mapping habitat extent, remote sensing provides key environmental descriptors, such as vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI), surface moisture, canopy structure, and seasonal phenology, which can enhance habitat classification and potentially improve predictive models14.

Recent studies showcase the potential of integrating remote sensing variables15 with in-situ data for habitat modelling using knowledge-based classifiers16, data-driven machine learning approaches17,18 and hierarchical approaches19. However, a vast majority of studies focused on fine-scale mapping at regional scale, particularly within protected areas20,21. Land cover mapping has been extensively developed at global and continental scales22,23,24,25, but these products remain too broad for ecological applications that require habitats or vegetation types. Reviews of habitat mapping with remote sensing26,27 have highlighted that existing studies target specific formations or biomes, including forests18,28,29,30,31, wetlands32,33, grasslands16,34,35, coastal dunes36 and arid landscapes37. Individual suitability maps for most terrestrial EUNIS habitats at level 3 have been developed previously38,39. Yet, integrating them into a single map proved challenging. Despite recent methodological advancements40,41, a comprehensive, continental-scale map of EUNIS habitats has yet to be developed. To this end, there is a growing need to integrate different datasets and leverage the scalability and flexibility of Machine Learning (ML) methods for large-scale mapping of multiple habitats.

Here we develop and present high spatial and thematic resolution predictions of EUNIS (level 3) habitats across Europe. We provide habitat distribution maps at 100-m resolution by harnessing high-resolution and ecologically relevant remote sensing variables, and validate these habitat maps using three independent datasets and provided them to the community via public repositories.

Methods

Habitat modelling predicts each habitat class at specific locations given environmental predictors. In this study, we used the EUNIS habitat nomenclature4,10, focusing on terrestrial habitats at level 3. This includes over 250 distinct habitat classes within nine broader formations. To handle the discrete nature of habitat classes, we employed a classification approach to accurately assign habitat types to specific locations based on predictor variables available as gridded raster data at the European extent.

In practice, we built a set of multi-class machine learning models, where each model classifies data into one of multiple habitat classes. This contrasts with independent binary classifiers38, which would require training separate models for each habitat class. The use of such classifiers could potentially lead to inconsistencies and loss of contextual relationships among classes. Joint modelling in multi-class models implicitly accounts for associations between multiple habitats, allowing less prevalent classes to borrow statistical power from more common ones.

The presence of multiple habitats from different EUNIS level 1 formations within the same spatial unit can create mosaics, introduce ambiguity and potentially reduce model accuracy. To address this, we leveraged the hierarchical structure of habitat classes by training separate multi-class models at EUNIS level 3, each restricted to habitats within a single level 1 group, ensuring that each model focuses only on a subset of ecologically related habitats and aligning with the structure of the EUNIS system.

In the following, we detail the data sources (habitat in-situ information and environmental predictors), the detailed modelling and prediction strategies, the validation and finally the pipeline for producing spatially contiguous maps integrating all habitat classes i.e., wall-to-wall map.

Data

Study area

The study extent is defined by the EEA39 region. This includes the 27 EU member states, three EFTA countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway), and nine additional collaborating countries: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Switzerland, Türkiye, and the United Kingdom. This extent aligns with the Corine land cover mask used further down for integrating habitat predictions into a wall-to-wall map.

Habitat plots

Vegetation plots from the European Vegetation Archive (EVA)12,42 spanning the period 1990–2021 served as ground truth data for training and testing the model across Europe. Each vegetation plot record was translated to the EUNIS typology at level 3 based on its species composition, using the EUNIS-ESy expert system10. The EUNIS classification includes nine revised habitat formations: MA (Marine habitats), N (Coastal habitats), P (Inland surface waters), Q (Wetlands), R (Grasslands), S (Shrublands - heathlands, scrub, and tundra), T (Forests), U (Sparsely vegetated habitats), and V (Vegetated man-made habitats).

An EVA vegetation plot typically contains a full list of co-occurring vascular plant species, often also a list of co-occurring bryophytes and lichens, estimates of cover-abundance of each species and various additional information on vegetation structure and layering. The dataset included vegetation plots assigned to the target habitat formations: saltmarshes (MA2), coastal habitats (N), wetlands (Q), grasslands (R), shrublands (S), forests (T), sparsely vegetated habitats (U), and man-made habitats (V). We focused on the terrestrial realm and therefore excluded other marine habitats and inland waters, as their classification is not based on vegetation and consequently, they cannot be classified by a vegetation-based expert system.

Vegetation plots with no cover-abundance information for individual species were excluded. Further, plots smaller than 1 m2, larger than 1000 m2, without geographical coordinates and with reported uncertainty of the coordinates larger than 100 m were also excluded. The resulting dataset43 contained a total of 597,819 georeferenced plots, heterogeneously distributed across Europe (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Habitat datasets for validation

To evaluate the quality of the habitat maps, we have used two habitat occurrence datasets: a hold-out of habitat observations from the Netherlands (NL) and the French Forest Inventory (IFN). The IFN dataset was previously used to test the classification of vegetation plots into habitat types in the EUNIS-ESy2. However, both datasets contain geolocated habitat observations that were not used for training the habitat distribution models.

The NL dataset contains 49,512 vegetation plots (Fig. 2) from the Landelijke Vegetatie Databank (LVD)44,45, sampled between 2010 and 2022 and classified into EUNIS level 3 classes following the same methodology as the EVA dataset.

The French Forest Inventory (Inventaire Forestier National, IFN)46 is a nationwide program monitoring French forests annually on a systematic grid of 2000 m² plots. On each plot, the habitat at the centre is identified using ecoregion-specific identification keys, and additional habitats may be noted. These observations are linked to national typologies (HABREF), as well as EUNIS Level 3. Habitat data are currently available through DataIFN only for ecological regions with published identification keys (Grand-Est, Vosges, Jura, southern Alps). We used 21,252 plots surveyed between 2013 and 2021 (Fig. 2).

Additionally, we used the MAES/EUNIS habitat map for Austria (AT) (2021)47, a fine-scale 10-m resolution raster (~8 million classified grid cells) compilation of biotope mapping data from Austrian federal states, harmonised to EUNIS Level 3 classes. It provides full national coverage across habitat types.

Environmental predictors

To train the models on the vegetation plots, we built a comprehensive database of environmental predictors at the highest possible spatial resolution, which are ecologically meaningful to predict habitats across Europe14,15. These variables had to be available at least at 1 km resolution within our study area. We selected a set of the least correlated environmental variables, including climate, topography, hydrography, geology, and soil (Table 2). These data were complemented by remote sensing (RS) products (Table 3) describing vegetation structure, phenology and productivity parameters and landscape composition, capturing functional and structural properties relevant to EUNIS level 3 habitats.

Phenology and productivity metrics from the Plant Phenology Index (PPI) summarize seasonal vegetation dynamics and photosynthetic activity. These are particularly effective in distinguishing habitats whose definitions depend on growing-season timing, length, amplitude and productivity. For instance, dry grasslands green up earlier and senesce faster due to soil moisture limitation than mesic grasslands, which have longer, more productive growing seasons48. Similarly, annual croplands display abrupt growth and senescence peaks associated with sowing and harvest49. Deciduous and evergreen forests differ in their phenological amplitude, with deciduous forests exhibiting a broad-amplitude seasonal cycle of leaf loss and regrowth, while evergreen forests maintain a narrow-amplitude cycle with year-round canopy50.

Vegetation structure was captured by several complementary metrics, including the Leaf Area Index (LAI) for foliage density and vertical layering, canopy cover for horizontal tree crown extent, and canopy height to capture forest stature/successional stage, which together allow differentiation between open shrublands, tall-herb communities, sparse versus dense forests, and young plantations versus old-growth stands51,52,53.

Hydrological regimes were represented by inundation seasonality, essential for separating wetland and riparian habitats54.

Finally, land-cover composition from ESA WorldCover55 summarized proportions of surrounding classes, critical for context-dependent habitats whose definition depends on adjacency or mosaics, such as dune slacks surrounded by coastal dunes, agroforestry systems embedded in croplands, or heathlands interspersed with grasslands. Direct use of raw multispectral imagery (e.g., Landsat, Sentinel-2) was not considered, since the higher-level biophysical and land-cover products employed here are already derived from these missions and provide ecologically validated, interpretable indicators.

All RS datasets were harmonized to a 100 m grid: continuous variables were resampled using bilinear interpolation, while categorical land-cover classes were aggregated as proportions within each 100-m cell. Remote sensing predictors spanned different periods depending on availability of EO products. To reduce interannual variability and short-term noise, we averaged them over their respective ranges to capture stable environmental regimes.

Ensemble machine learning framework

Overview

To address uncertainties arising from model choices and data sampling, we employed an ensemble modelling approach56,57.

First, the uncertainty arising from model choices stems from different algorithms with varying functional forms58,59. For instance, decision-tree approaches create trees with different depths, capturing interactions between variables whereas neural networks represent smooth, continuous responses, with wide architectures for recurring patterns and deep architectures for hierarchical representations60,61. To encompass the diversity of models, we created an ensemble of algorithms from different families of tree-based models as well as neural networks which meet a minimum performance requirement. Since decision trees excel with structured tabular data and neural networks with intricate feature interactions, combining them creates a more generalized and robust model, leveraging the strengths of each approach for improved predictive performance.

Second, we considered the uncertainty arising from different training data. Employing spatial block cross-validation41,62, we trained the model with 20% of the observations hidden at each iteration. This process was repeated, generating an ensemble of classifiers with access to distinct samples, thus accounting for data sampling uncertainty.

Selected ML algorithms

To achieve the best modelling performance, we employed well-known machine learning techniques, each with their advantages and disadvantages including bagging models, boosting models, and neural networks (Supplementary Table 2).

Bagging models, also known as bootstrap aggregating models, enhance predictive accuracy and alleviate overfitting by training multiple individual estimator models on various subsets of both the training data and predictor variables. This approach harnesses collective knowledge to improve results. A notable example of bagging is the Random Forest (RF) algorithm63, which employs classification or regression trees as base estimators.

Boosting models progressively train weak learners to create a robust learner by assigning greater emphasis to incorrectly classified instances. This iterative process leads to improved overall predictive performance.

-

XGBoost64: This optimized gradient boosting algorithm merges tree-based models with regularization techniques, resulting in highly accurate and efficient predictions.

-

CatBoost65: Tailored for categorical variable handling, CatBoost employs gradient-based strategies, ordered boosting, and innovative encoding methods to enhance accuracy and manage categorical features effectively.

LightGBM66: A specialized form of boosting, LightGBM employs a gradient-based decision tree algorithm that optimizes training speed through leaf-wise growth and histogram-based optimizations, all while maintaining strong predictive performance.

Neural networks60 are computational models that feature interconnected nodes, or “neurons” organised in layers. These networks learn to extract meaningful features by adjusting connection weights and biases during training. In this study, we used several architectures for fully Connected Neural Networks (Multi-layer Perceptron - MLP) with a single shallow hidden layer, a single wide hidden layer, two hidden layers and three hidden layers (Supplementary Table 2).

Dealing with habitat class imbalance

Class imbalance arises from differences in habitat prevalence, either due to uneven sampling effort or restricted extent in the case of rare habitats. To address this, we evaluated imbalance correction strategies that modify the optimization objective rather than under-sample frequent habitats or oversample rare habitats from the training data. The choice of method depends on the machine learning framework.

For tree-based algorithms (RF, XGBoost, CatBoost and LightGBM), we evaluated class weighting, a technique that assigns to each class a weight inversely proportional to its frequency to balance its relative importance in the overall optimization. In RF this is achieved via weights in the splitting criterion, while in boosting algorithms (XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM) it corresponds to a weighted version of the multi-class log loss.

For neural networks, the baseline categorical cross-entropy loss can be extended with class weights, yielding the Weighted Categorical Cross-Entropy (WCE), which is conceptually equivalent to the weighted log loss in tree ensembles. Weighted categorical cross-entropy (WCE) in neural networks follows the same principle as weighted log loss in boosting algorithms (XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM) and class weighting in RF, namely to increase the influence of rare classes on the optimization objective. While the underlying formulations differ across model families, the methods are functionally comparable as imbalance correction strategies67.

Focal loss68 (FL) is a modification of the standard Cross Entropy loss that specifically targets imbalanced classification problems. It introduces a focusing parameter “gamma” to down-weight the contribution of well-classified examples, putting more emphasis on hard, misclassified examples. This helps to alleviate the dominating effect of the majority class and enables the model to focus more on the minority class instances during model training. Label Distribution Aware Margin69 (LDAM) loss addresses class imbalance by assigning distinct margins to classes based on their distribution characteristics. These margins represent class boundary separation and control intra-class and inter-class distinctions. LDAM loss aims to penalize misclassifications of minority class examples more, encouraging the model to better account for underrepresented classes. Both FL and LDAM can be combined with class weights to further account for imbalance.

To ensure that imbalance correction improved performance, each algorithm was also evaluated against a baseline mode without correction. The strategy retained for each model and habitat type (Supplementary Table 3) reflects the optimal choice relative to this baseline.

Ensemble model training

Overview

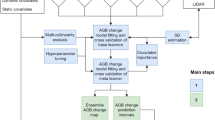

For each habitat type at level 1, we trained an ensemble of multi-class models to predict the most likely EUNIS level 3 class within the target formation (i.e., level 1) following the steps depicted in Fig. 3a:

-

1.

Create a dataset containing observations from classes (EUNIS level 3 within each formation (EUNIS level 1).

-

2.

Generate a spatial block partition of the selected observations for cross-validation.

-

3.

Train an ensemble multi-class model for all classes within each formation, this step encompasses the feature pre-processing and hyperparameter tuning.

-

4.

Select the best algorithm(s) in each family (bagging, boosting, neural networks) as well as the imbalance correction strategy based on overall cross-validation predictive performances.

In the following, we provide more details about the input data, pre-processing (feature pre-processing, data partitioning) and hyperparameter tuning steps.

Input data

For training the models, the dataset consisted of the geolocated level 3 habitat observations from the EVA dataset and the abiotic and RS products predictors extracted at the highest spatial resolution available for the observations’ locations. Similarly, for each external evaluation dataset (NL, AT, IFN), the dataset consisted of the map of habitat observations annotated at level 3 and the abiotic and the RS predictor maps of the validation areas.

Preprocessing steps

Spatial Block-CV partitioning

We establish a spatial block partition of the annotated dataset for cross-validation, as follows:

-

1.

Grid Division: The study’s spatial domain was divided into a grid composed of cells measuring 100 km × 100 km each. Several grid sizes (10 km, 20 km, 50 km, 100 km, 200 km, 500 km) were tested to determine the optimal granularity.

-

2.

Class Frequency Computation: Within each grid cell, we calculated the frequencies of different habitat classes.

-

3.

Cell Block Allocation: The grid cells were then partitioned into five distinct spatial blocks, ensuring that every habitat class is adequately represented within each block. This is accomplished using the IterativeStratification70 module found in the Python scikit-multilearn package70. This algorithm processes cells in order from the rarest to the most frequent labels and assigns them to the block that best preserves the global class distribution, thereby ensuring that all habitat classes are represented in each block.

-

4.

Observation Assignment: Every individual habitat observation was assigned to the spatial block corresponding to the cell within which it resides.

-

5.

Balanced Observations:We verified that the number of observations and habitat classes was reasonably balanced across the five blocks. Imbalance was defined as cases where one or more blocks contained disproportionately fewer observations. In such cases, the grid cell size was decreased (e.g., from 100 km to 50 km or 10 km) to generate more cells and redistribute observations, and the procedure was repeated from step 1. The final grid size retained for the analyses was 100 km, which provided the best compromise between spatial independence and balanced class representation.

This spatial block partitioning methodology serves two crucial purposes. First, it amalgamates observations from proximate locations into the same partitions. This prevents potential overestimation of predictive performance stemming from data leakage induced by spatial autocorrelation. Second, in instances where multiple neighbouring habitats are observed and co-occurring in the same location, this technique exposes the model to a comprehensive array of potential responses for the same predictors. As a result, the model’s probabilities reflect the uncertainty inherent in the dataset.

Feature pre-processing

We employed tailored feature pre-processing procedures customised to the nature of the features and the specific demands of the machine learning algorithms (Supplementary Table 1). These pre-processing steps were seamlessly integrated within a unified pipeline that encompasses both algorithm training and prediction tasks.

Hyperparameter tuning

For each individual machine learning algorithm, specific hyperparameters can be configured to control model complexity and optimization settings. To select the optimal hyperparameters for each modelling task (formation), a distinct 10% subset of the training data was set aside for hyperparameter tuning, with a focus on achieving high adjusted balanced accuracy as the objective. Our hyperparameter tuning process unfolds as follows:

-

1.

We kept problem-specific parameters (such as objective function and metrics) at their default values, which are tailored for multi-class classification. These parameters are solely defined by the output variable type (here discrete classes).

-

2.

Initially, a fixed set of architectures was generated, and we explored the best optimizer configurations without incorporating regularisation. For algorithms that are iteratively optimised, like boosting models and neural networks, we implemented early stopping callbacks to cease training when validation performance begins to decline, thereby avoiding overfitting.

-

3.

Subsequently, we fine-tuned regularisation parameters to manage model complexity, leveraging a hold-out validation dataset. In the case of Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs), given their computational complexity, we resorted to a grid search with a constrained array of configurations. We applied temperature scaling to MLPs to enhance the calibration of probabilities, especially when imbalance correction techniques are applied. This step was not required for bagging and boosting algorithms.

-

4.

Bayesian optimization techniques were employed for bagging and boosting algorithms to navigate the hyperparameter space and identify the most optimal hyperparameter settings. This Bayesian hyperparameter tuning, facilitated by the optuna package71, involves a probabilistic surrogate function known as the acquisition function. This function estimates the potential improvement in the objective function based on different hyperparameter combinations. The algorithm iteratively assesses various hyperparameter sets, updating the surrogate function and hyperparameter space accordingly.

-

5.

Finally, we leveraged the performance outcomes on the test set to make informed selections of the best-performing algorithm(s) within each algorithm family.

This comprehensive and enhanced approach ensures the fine-tuning of algorithmic parameters, ultimately leading to selecting the most suitable models based on their predictive performance (Supplementary Table 3).

Decision trees excel with structured tabular data and neural networks with intricate feature interactions. Therefore, combining them creates a more generalized and robust model, leveraging the strengths of each approach for improved predictive performance.

Ensemble forecasting and uncertainty

Upon completion of the training process, we obtained a collection of trained machine learning algorithms alongside their associated feature pre-processing pipelines for every cross-validation fold. The ensemble model is a simple voting classifier, combining predictions from all individual models and assigning weights based on their respective rankings in terms of predictive performance (Fig. 3b).

From the collective predictions of the ensemble, we extracted various metrics of uncertainty:

-

Model Uncertainty: The variability in predictions among the constituent models within the ensemble indicates sensitivity to the choice of model.

-

Data Sampling Uncertainty: The diversity in predictions across different folds within the ensemble underscores the sensitivity to variations in data sampling.

This uncertainty can be quantified at the level of individual pixels through different metrics, including:

-

Confidence Scores: These scores represent the probability associated with the most probable class. Higher scores indicate more confidence in the chosen class, but the number of classes affects this measure. For example, a 30% confidence probability in a problem with 200 classes carries different implications than the same probability in a problem with just 3 classes.

-

Committee Averaging Scores: These scores were calculated based on the proportion of voters (model x fold) that have predicted each class as the most likely. This measurement offers insights into the level of consensus or disagreement among models:

-

CA = 1: unanimous agreement among all models on prediction of the most likely habitat.

-

0 < CA < 1: varying degrees of disagreement among models.

-

CA ~ 0: Pronounced disagreement among models.

-

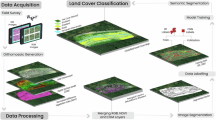

Habitat mapping workflow

The ensemble multi-class habitat models combined with a set of decision rules were used to generate wall-to-wall habitat maps for Europe. The workflow proceeds in four steps depicted in Fig. 4. First, ensemble models predict habitat class probabilities (Step 1). Second, regional filtering rules constrain predictions to habitats that occur in their biogeographic regions (Step 2). Third, land-cover filtering rules refine probabilities by enforcing compatibility between habitats and their associated land-cover classes (Step 3). Finally, land cover-based priority rules are applied to generate the final categorical habitat map (Step 4). These steps produce three complementary habitat mapping products (continuous probabilities for each habitat class, top 3 categorical maps with confidence and the final wall-to-wall map).

Step 1: Ensemble models

We used the ensemble model to predict the probabilities of each EUNIS level 3 class for each EUNIS 1 formation. Figure 5 shows an example map of habitat probability for the class of Fagus forests on non-acid soils (T17).

Step 2: Regional filtering rules

Location is an intrinsic part of the EUNIS habitat classification. Some habitats are, by definition, associated with specific biogeographic regions (e.g., Macaronesian heathy forest). Although the climate can be a good approximator of biogeographic regions, we applied a post-hoc filtering to select the most likely habitat only amongst those which occur in the biogeographic region of the prediction pixel. This step also allowed to account for the habitats’ range of occurrence (e.g., Carpathian travertine fens).

For inland habitats, we used the ecoregions of the world72. For coastal habitats, we used the official EEA coastline delineation with an inland depth of 5 km away from the coastline. Using these layers and vegetation plot data from the EVA, we computed a matrix of association between each EUNIS level 3 class and the ecoregion/coastline, which were then used to generate regional masks for each modelled class.

EUNIS class probabilities and ranking (output product n°1) was generated by multiplying together the data cubes of the class-wise regional masks (step 2) and their model predicted probabilities (step 1). This output can be used to generate maps of the most likely habitat class at level 3 for each formation or aggregated at level 2. Figure 6 illustrates that for Heathlands, Scrub and Tundra (S) habitat classes, annotated at level 2, whereas Figs. 7, 8 illustrate that for broadleaved and coniferous forests respectively at level 3. These outputs are not filtered by land use and are therefore less sensitive to the minimum mapping unit of the land-cover/land-use maps.

Step 3: Land cover filtering rules

Here, we used crosswalks to select for each EUNIS habitat class the associated land cover classes. From that, we generated land cover masks. The three most likely (top 3) EUNIS classes and their confidence scores (output product n°2) within each EUNIS 1 formation were obtained by multiplying together the data cubes of the class-wise land cover masks (step 3) with the EUNIS class probabilities (output product n°1). After rescaling, we selected the top 3 classes and their corresponding probabilities i.e., confidence scores. Only classes with non-zero probabilities were kept, therefore in some cases the top 2 and top 3 classes were undefined. Figure 9 shows an example of a map of the most likely habitat (top 1) for vegetated man-made habitats, accompanied by its confidence map. This step refines the probabilities before the final wall-to-wall mapping (Step 4).

Step 4: Wall-to-wall mapping

Finally, we applied land cover-based priority rules (output product n°4) to determine the prevailing EUNIS 1 formation at each pixel to map the final habitat class at EUNIS level 3 (output product n°3). Non-vegetated land cover classes were assigned broad habitat categories: Urban for artificial areas and Inland water further split into Water course, lakes and reservoirs, transitional water and sea/ocean.

Steps 1-2 were done only once at European scale for each EUNIS 1 formation.

Steps 3 and 4 required the definition of crosswalk rules tailored to the underlying land cover product. We provided the worksheet summarising the crosswalk rules for Corine Land Cover, which was used as a mask for producing the final habitat maps. The spatial resolution of the final layer as well as the habitat extents are thus controlled by the chosen land cover product. Any potential user can use its preferred land cover layer to refine the spatial resolution of the final product.

Output products

All the following maps have been produced at 100 m resolution across Europe:

-

1.

Continuous map of all EUNIS level 3 class probabilities.

-

2.

Categorical map of the top 3 most likely habitats and continuous map of their confidence scores at level 3 within each formation.

-

3.

Categorical wall-to-wall map of the top 3 EUNIS habitats at level 3 across all formations (previewed in Fig. 10), with a legend and a QGIS style file.

-

4.

An Excel sheet summarising the crosswalk and priority rules from Corine to EUNIS habitats.

Data Records

The dataset is available at Zenodo73 and is released under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC-BY 4.0) license, allowing reuse with attribution. It provides wall-to-wall habitat maps for Europe at 100 m resolution, classified to EUNIS level 3 habitats and covering terrestrial, freshwater, and coastal realms. All data are distributed in GeoTIFF format, complemented by CSV legends and style files for visualization.

Technical specifications

-

Spatial resolution: 100 m

-

Spatial extent: 900000.0000,7400000.0000,900000.0000,5500000.0000

-

Coordinate Reference System: ETRS89-LAEA Europe (EPSG:3035)

-

Data type: unsigned integer (16-bit for habitat class maps, 8-bit for confidence maps)

-

NODATA: 65535 for habitat class maps, 255 for confidence maps

Folder structure

The dataset corresponds directly to the four output products described above:

-

1.

Continuous map of all EUNIS Level 3 class probabilities

-

Provided in the folder habitat_probability/

-

One GeoTIFF per EUNIS Level 1 formation (e.g., MA2.tif, N.tif, R.tif, T.tif), each containing stacked probability bands for all Level 3 habitats within the formation.

-

-

2.

Categorical maps of the top-3 most likely habitats and their confidence scores (per formation)

-

Provided in the folder topk_habitats/

-

[code_level_1]_topk.tif: top-1, top-2, and top-3 predicted classes (Bands 1–3)

-

[code_level_1]_topk_confidence.tif: corresponding confidence scores (Bands 1–3)

-

[code_level_1]_legend.csv: legend mapping integer codes to habitat classes.

-

-

3.

Categorical map of the top-3 EUNIS habitats across all formations

-

Provided in the folder wall_to_wall/

-

eunis_dominant.tif: top-1 most likely habitat class

-

eunis_top2.tif: top-2 most likely habitat class

-

eunis_top3.tif: top-3 most likely habitat class

-

Additional files: eunis_legend_detailed.csv (full class legend), eunis_legend_style.qml (QGIS style file).

-

-

4.

Crosswalk and priority rules from Corine Land Cover to EUNIS habitats

-

Provided as documented_cross_walks.csv (spreadsheet with crosswalk and priority rules).

-

Technical Validation

Quantitative evaluation

Habitat maps were cross-validated at the European scale on the EVA dataset and evaluated by comparison with independent datasets from the Netherlands (NL), Austria (AT) and France (IFN). We evaluated the predictive quality in terms of recall (proportion of instances of a given habitat class correctly classified), precision (proportion of instances predicted as a given habitat class that truly belong to that class), and F1-score (harmonic mean of recall and precision) for each EUNIS level 3 class. In multi-class settings, recall and precision often exhibit a trade-off because improving recall (capturing more true positives) can lead to an increase in false positives, lowering precision, while tightening classification to improve precision may exclude some true positives, reducing recall.

Table 4 summarizes the distribution of these class-wise metrics (mean and standard deviation) within each EUNIS level 1 formation. Detailed performances for EUNIS level 3 classes across the validation datasets, as well as cross-validation performances, are also provided in the Supplementary Materials for each formation including: Saltmarshes (Table S4), Coastal habitats (Table S5), Wetlands (Table S6), Grasslands (Table S7), Scrub and Tundra (Table S8), Forests (Table S9) and Sparsely vegetated habitats (Table S10).

The spatial-block cross-validation (EVA) results show strong predictive performance, with most classes achieving very good F1-scores. Prediction quality varies depending on the number of habitat classes within the formation. Formations with fewer classes such as saltmarshes or those strongly shaped by abiotic elements (e.g., soil type, landscape structure) such as coastal, wetland, and sparsely vegetated habitats exhibit consistently high recall and precision. In contrast, grasslands, shrublands, and forests obtained variable predictive scores across classes reflecting their structural complexity and compositional diversity.

In sparsely vegetated habitats, precision and recall were well balanced. However, across the other formations, distinct trade-offs emerged. Grasslands, shrublands, and forests exhibited higher precision, reflecting more conservative models, whereas coastal and wetland habitats showed higher recall, indicating a tendency toward over-prediction.

When evaluated on external datasets, the habitat maps performed well, albeit slightly lower than in cross-validation, except for coastal and salt marsh habitats. Similar trade-offs across formations persisted, with the largest performance drop observed for the Austrian dataset, likely due to its higher resolution (10 m) compared to the model’s 100-m resolution, making fine scale matching more challenging.

In summary, the maps achieved strong predictive performance, with F1-scores ranging from 0.61 to 0.94 in spatial cross-validation and from 0.33 to 0.95 in external validation datasets. Low performance was often associated with habitats of limited spatial extent, prompting the use of an ecoregion filtering step. In such cases, accuracy improved when considering the top three predictions rather than only the most likely class.

Known limitations

Validation scope

We selected the validation areas based on available independent datasets covering different biogeographic regions: Alpine and Continental (Austria), Atlantic (Netherlands), Mediterranean, Alpine, and Continental (IFN). However, there are several regions that were not assessed due to a lack of independent data.

European habitat coverage

While we tried to be as exhaustive as possible in covering all habitat types in Europe, our map covers only a subset of EUNIS habitats which were classified by an expert system from plant community composition. Some of the missing habitats are challenging to define based on vegetation plot data (e.g., caves, glaciers) or in the case of anthropogenic habitats (e.g., tree plantations) hard to distinguish from semi-natural habitats. Habitats with a one-to-one association to a particular land cover class (e.g., glaciers, plantations) were incorporated in Step 4. Additionally, for statistical reasons, habitats with less than 5 occurrences in the curated EVA database were also discarded. Moreover, freshwater habitats were not mapped due to ongoing revisions of the classification system and lack of water quality predictors. Although there are some existing remote sensing products describing water body turbidity and trophic state, they are only available for a few large water bodies, and we found little overlap with freshwater vegetation plots. Finally, due to the choice of land use map (Corine land cover) which has a minimum mapping unit of 1 ha, linear habitats (e.g., hedgerows, small streams) and other smaller extent habitats could not be used in mapping.

Missing predictors

Some habitat classes with low validation scores were linked to humid soil habitats (R53, R65), those affected by land use pressures such as grazing (R1N) and abandoned agricultural lands (S82). Future improvements should integrate predictors for soil moisture (beyond the included inundation occurrence), land use history, and human footprint. Additionally, certain low-performing classes, particularly those found at habitat edges such as woodland fringes (R53), could benefit from incorporating spatial landscape structure using deep convolutional neural networks with satellite imagery. The use of LiDAR imagery could also help in distinguishing classes with high structural complexity whereas incorporating seasonal remote sensing indicators could better capture the phenology of habitats.

Data availability

The primary dataset73 produced by this study is openly available at Zenodo and is released under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC-BY 4.0) license, allowing reuse with attribution. Exact file inventory, formats, and folder structure are provided in the Data Records section. For reproducibility purposes, spatial habitat observation records43 are available at Zenodo under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

Code availability

The code to run the habitat modelling, evaluation and mapping workflow is provided in: https://github.com/bettasimousss/eunis-ml-mapping.git.

References

AEE. The European Environment: State and Outlook 2020: Knowledge for Transition to a Sustainable Europe. (Publications Office, LU, 2019).

Moss, D. & Davies, C. E. European topic centre on nature protection and biodiversity eunis habitat classification 2001 WORK PROGRAMME.

Davies, C. E., Moss, D. & Hill, M. O. Eunis habitat classification revised (2004).

Chytrý, M. et al. EUNIS Habitat Classification: Expert system, characteristic species combinations and distribution maps of European habitats. Appl. Veg. Sci. 23, 648–675 (2020).

European Commission. Directorate General for the Environment. European Red List of Habitats. Part 2, Terrestrial and Freshwater Habitats. (Publications Office, LU, 2016).

Bohn, U. et al. Karte Der Natürlichen Vegetation Europas/Map of the Natural Vegetation of Europe. (Landwirtschaftsverlag, Münster, 2003).

Bohn, U., Zazanashvili, N. & Nakhutsrishvili, G. The Map of the Natural Vegetation of Europe and its application in the Caucasus Ecoregion 175 (2007).

Mucina, L. et al. Vegetation of Europe: hierarchical floristic classification system of vascular plant, bryophyte, lichen, and algal communities. Appl. Veg. Sci. 19(Suppl.), 3–264 (2016).

European Environment Agency. EUNIS terrestrial habitat classification 2021_1 including crosswalks (2025).

Chytrý, M. et al. EUNIS-ESy: Expert system for automatic classification of European vegetation plots to EUNIS habitats (v2021-06-01). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.4812736 (2021).

Chytrý, M. et al. FloraVeg.EU — An online database of European vegetation, habitats and flora. Appl. Veg. Sci. 27, e12798 (2024).

Chytrý, M. et al. European Vegetation Archive (EVA): an integrated database of European vegetation plots. Appl. Veg. Sci. 19, 173–180 (2016).

Schaminée, J. H. J., Hennekens, S. M. & Ozinga, W. A. Use of the ecological information system SynBioSys for the analysis of large datasets. J. Veg. Sci. 18, 463–470 (2007).

EEA & MNHN. Terrestrial Habitat Mapping in Europe: An Overview. (Publications Office, LU, 2014).

Wang, R. & Gamon, J. A. Remote sensing of terrestrial plant biodiversity. Remote Sens. Environ. 231, 111218 (2019).

Adamo, M. et al. Knowledge-Based Classification of Grassland Ecosystem Based on Multi-Temporal WorldView-2 Data and FAO-LCCS Taxonomy. Remote Sens. 12, 1447 (2020).

Wicaksono, P., Aryaguna, P. A. & Lazuardi, W. Benthic Habitat Mapping Model and Cross Validation Using Machine-Learning Classification Algorithms. Remote Sens. 11, 1279 (2019).

Agrillo, E. et al. Earth Observation and Biodiversity Big Data for Forest Habitat Types Classification and Mapping. Remote Sens. 13, 1231 (2021).

Gavish, Y. et al. Comparing the performance of flat and hierarchical Habitat/Land-Cover classification models in a NATURA 2000 site. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 136, 1–12 (2018).

Le Dez, M., Robin, M. & Launeau, P. Contribution of Sentinel-2 satellite images for habitat mapping of the Natura 2000 site ‘Estuaire de la Loire’ (France). Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 24, 100637 (2021).

Lafitte, T., Robin, M., Launeau, P. & Debaine, F. Remote Sensing for Mapping Natura 2000 Habitats in the Brière Marshes: Setting Up a Long-Term Monitoring Strategy to Understand Changes. Remote Sens. 16, 2708 (2024).

Malinowski, R. et al. S2GLC 2017, Sentinel-2 global land cover map of Europe at 10 m. Remote Sens. 12, 3456 (2020).

ESA Climate Change Initiative. ESA Climate Change Initiative Land Cover time series (1992–2020). ESA Clim. Off. (2020).

Brown, C. F., Brumby, S. & Guzder-Williams, B. Dynamic World, Near real-time 10 m land use land cover mapping. Nature 608, 480–486 (2022).

Buchhorn, M. et al. Copernicus Global Land Service: Land Cover 100m: collection 3: epoch 2019: Globe. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.3939050 (2020).

Corbane, C. et al. Remote sensing for mapping natural habitats and their conservation status: New developments and applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 160, 1–6 (2015).

Nagendra, H. et al. Remote sensing for conservation monitoring: Assessing protected areas, habitat extent, habitat condition, species diversity, and threats. Ecol. Indic. 33, 45–59 (2013).

Hansen, M. C. et al. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science 342, 850–853 (2013).

Giannetti, F. et al. European Forest Types: toward an automated classification. Ann. For. Sci. 75, 6 (2018).

Immitzer, M. et al. Optimal Input Features for Tree Species Classification in Central Europe Based on Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sens. 11, 2599 (2019).

Asner, G. P. et al. Carnegie airborne observatory: in-flight fusion of hyperspectral imaging and waveform light detection and ranging for three-dimensional studies of ecosystems. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 1, 013536 (2007).

Davidson, N. C., Finlayson, C. M. & McInnes, R. J. Global Wetland Map and Its Relevance to Wetland Conservation and Management. Remote Sens. 10, 1912 (2018).

Adam, E., Mutanga, O. & Rugege, D. Multispectral and hyperspectral remote sensing for identification and mapping of wetland vegetation: a review. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 18, 281–296 (2010).

Rocchini, D. et al. Remotely sensed spectral heterogeneity as a proxy of species diversity: recent advances and open challenges. Ecol. Inform. 5, 318–329 (2010).

Huber, N. et al. Countrywide classification of permanent grassland habitats at high spatial resolution. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 9, 133–151 (2023).

Marzialetti, F. et al. Capturing Coastal Dune Natural Vegetation Types Using a Phenology-Based Mapping Approach: The Potential of Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. 11, 1506 (2019).

Okin, G. S., Roberts, D. A., Murray, B. & Okin, W. J. Practical limits on hyperspectral vegetation discrimination in arid and semiarid environments. Remote Sens. Environ. 77, 212–225 (2001).

Hennekens, S. Distribution and habitat suitability maps of revised EUNIS coastal and wetland habitats. ETC/BD report to the EEA (2019).

Hennekens, S. Distribution and habitat suitability maps of revised EUNIS Marine saltmarshes and Sparsely vegetated habitats. ETC/BD report to the EEA (2020).

Álvarez‐Martínez, J. M. et al. Modelling the area of occupancy of habitat types with remote sensing. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 580–593 (2018).

Jiménez‐Alfaro, B. et al. Modelling the distribution and compositional variation of plant communities at the continental scale. Divers. Distrib. 24, 978–990 (2018).

European Vegetation Survey, The IAVS Working Group. EVA project # 217 – 2024-08-01 EUNIS Habitat Maps: Enhancing Thematic and Spatial Resolution for Europe through Machine Learning - W. Thuiller: SELECTION 2024-09-16. Masaryk University, Faculty of Science, Department of Botany and Zoology https://doi.org/10.58060/6N57-HH22 (2024).

Si-Moussi, S. et al. Habitat Observations for European Habitat Mapping. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.16944381 (2025).

Schaminée, J., Hennekens, S. & Ozinga, W. The Dutch National Vegetation Database. Biodivers. Ecol. 4, 201–209 (2012).

Hennekens, S. NDFF Dutch vegetation database. Dutch National Database of Flora and Fauna (NDFF) https://doi.org/10.15468/KSQXEP (2018).

IGN – Inventaire Forestier National Français. Données brutes, Campagnes annuelles 2005 et suivantes (2022).

Umweltbundesamt. MAES/EUNIS habitat map Austria 10m. 56.1 MBytes PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.934147 (2021).

Thoma, D. & Thoma, D. Landscape Phenology, Vegetation Condition, and Relations with Climate at Curecanti National Recreation Area, 2000?2019. https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2307122, https://doi.org/10.36967/2307122 (2025).

Zeng, L., Wardlow, B. D., Xiang, D., Hu, S. & Li, D. A review of vegetation phenological metrics extraction using time-series, multispectral satellite data. Remote Sens. Environ. 237, 111511 (2020).

Richardson, A. D. et al. Ecosystem warming extends vegetation activity but heightens vulnerability to cold temperatures. Nature 560, 368–371 (2018).

Fang, H., Baret, F., Plummer, S. & Schaepman‐Strub, G. An Overview of Global Leaf Area Index (LAI): Methods, Products, Validation, and Applications. Rev. Geophys. 57, 739–799 (2019).

Lang, N., Jetz, W., Schindler, K. & Wegner, J. D. A high-resolution canopy height model of the Earth. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1778–1789 (2023).

Shen, B. et al. Comparative Verification of Leaf Area Index Products for Different Grassland Types in Inner Mongolia. China. Remote Sens. 15, 4736 (2023).

Pekel, J.-F., Cottam, A., Gorelick, N. & Belward, A. S. High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 540, 418–422 (2016).

Zanaga, D. et al. ESA WorldCover 10 m 2021 v200. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.7254221 (2022).

Buisson, L., Thuiller, W., Casajus, N., Lek, S. & Grenouillet, G. Uncertainty in ensemble forecasting of species distribution. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 1145–1157 (2010).

Thuiller, W. Biodiversity - Climate Change and the Ecologist. Nature 448, 550–552 (2007).

Thuiller, W., Gueguen, M., Renaud, J., Karger, D. N. & Zimmermann, N. E. Uncertainty in ensembles of global biodiversity scenarios. Nat. Commun. 10 (2019).

Guisan, A., Thuiller, W. & Zimmermann, N. E. Habitat Suitability and Distribution Models: With Applications in R. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139028271 (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Cheng, H.-T. et al. Wide & Deep Learning for Recommender Systems. in Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Deep Learning for Recommender Systems 7–10, https://doi.org/10.1145/2988450.2988454 (ACM, Boston MA USA, 2016).

Roberts, D. R. et al. Cross-validation strategies for data with temporal, spatial, hierarchical, or phylogenetic structure. Ecography 40, 913–929 (2017).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. in (2016).

Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V. & Gulin, A. CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Bengio, S. et al.) vol. 31 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2018).

Ke, G. et al. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Guyon, I. et al.) vol. 30 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017).

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Deep Learning. (MIT Press, 2016).

Lin, T. -Y., Goyal, P., Girshick, R., He, K. & Dollar, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. in 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 2999–3007, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.324 (2017).

Cao, Y., Larsen, D. P. & Thorne, R. S.-J. Rare species in multivariate analysis for bioassessment: some considerations. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 20, 144–153 (2001).

Szymanski, P. & Kajdanowicz, T. Scikit-multilearn: a scikit-based Python environment for performing multi-label classification. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 20, 209–230.

Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T. & Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. in Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining 2623–2631. https://doi.org/10.1145/3292500.3330701 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2019).

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on Earth. Bioscience 51, 933–938 (2001).

Si-moussi, S. et al. EUNIS Habitat Maps: Enhancing Thematic and Spatial Resolution for Europe through Machine Learning. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16985100 (2025).

Karger, D. N. et al. Climatologies at high resolution for the earth’s land surface areas. Sci. Data 4, 1–20 (2017).

European Space Agency & Airbus. Copernicus DEM. https://doi.org/10.5270/ESA-c5d3d65 (2022).

European Environment Agency. EU-Hydro River Network Database 2006-2012 (vector), Europe - version 1.3, Nov. 2020. European Environment Agency https://doi.org/10.2909/393359A7-7EBD-4A52-80AC-1A18D5F3DB9C (2019).

European Commission, Joint Research Centre. European Soil Database v2 Raster Library 1kmx1km (2021).

Ballabio, C., Panagos, P. & Monatanarella, L. Mapping topsoil physical properties at European scale using the LUCAS database. Geoderma 261, 110–123 (2016).

Ballabio, C. et al. Mapping LUCAS topsoil chemical properties at European scale using Gaussian process regression. Geoderma 355, 113912 (2019).

European Environment Agency. Season Amplitude 2017-present (raster 10 m), Europe, yearly, Sept. 2021. European Environment Agency https://doi.org/10.2909/201EE90C-1971-4BDC-855E-9C9BCBC2C647 (2021).

Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. High Resolution Vegetation Phenology and Productivity: PPI Seasonal Trajectories (raster 10m) version 1 revision 1, Sep. 2021 (2021).

European Environment Agency. Season Length 2017-present (raster 10 m), Europe, yearly, Sept. 2021. European Environment Agency https://doi.org/10.2909/430C008C-7298-473E-A4B0-7C0A287446A6 (2021).

European Environment Agency. Slope of the Green-up Period 2017-present (raster 10 m), Europe, yearly, Sept. 2021. European Environment Agency https://doi.org/10.2909/ECBA54A6-BDC3-429E-8474-D8DCD0F20971 (2021).

European Environment Agency. Season Maximum Value 2017-present (raster 10 m), Europe, yearly, Sept. 2021. European Environment Agency https://doi.org/10.2909/774F56FC-E0E3-4918-AAEA-C181BAB0C2A3 (2021).

European Environment Agency. Total Productivity 2017-present (raster 10 m), Europe, yearly, Sept. 2021. European Environment Agency https://doi.org/10.2909/977E4BB8-407F-48EC-B4C4-403BCA5A6A3B (2021).

Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. Leaf Area Index 2014-present (raster 300 m), global, 10-daily - version 1. https://doi.org/10.2909/219fdc9f-616b-444b-a495-198f527b4722 (2017).

Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. Tree Cover Density 2020 (raster 10 m), pantropical, annual - version 1. https://doi.org/10.2909/59cc02d6-ddfe-4820-83cb-345205eacec5 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out in the frame of the EO4DIVERSITY project funded by the European Space Agency through its Biodiversity + Precursors programme. WT and S.SM also acknowledge funding from the Horizon Europe Natura Connect (No: 101060429) and OBSGESSION (No.: 101134954) projects. JCS was supported by Center for Ecological Dynamics in a Novel Biosphere (ECONOVO), funded by Danish National Research Foundation (grant DNRF173). GB was funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4 - Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree n. 3175 of 18 December 2021 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU; Award Number: Project code CN_00000033, Concession Decree No. 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP B63C22000650007, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center - NBFC”. We thank all data contributors to the European Vegetation Archive for providing vegetation plot data that supported our analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.T. and S.S.M. designed the study in collaboration with S.M. and S.H. S.S.M. designed the framework and ran all the models and predictions. S.M. and W.D.K. provided the remote sensing products. S.H. prepared the export from the E.V.A. database. W.T. and S.M. provided the financial support. W.T. and S.S.M. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript with the help of all co-authors. All authors contributed to data validation and interpretation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Si-Moussi, S., Hennekens, S., Mücher, S. et al. EUNIS habitat maps: enhancing thematic and spatial resolution for Europe through machine learning. Sci Data 12, 1976 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06235-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06235-7