Abstract

In the field of WiFi Sensing (WS), developing applications requires data with quality, quantity, and variability to enhance cross-domain capability.This paper presents EHUNAM, a comprehensive channel state information (CSI) dataset developed for various WS applications, with a primary focus on people counting (PC), human activity recognition (HAR), and machine activity recognition (MAR), while remaining suitable for additional tasks. The dataset was acquired using diverse equipment configurations and under different scenarios, ensuring versatility and representativeness. Beyond traditional applications, EHUNAM includes measurements for recognizing activities of home appliances and industrial machines. To achieve high accuracy in new settings, data was collected over 23 days in eight distinct environments, including an industrial scenario, involving 21 people and nine machines that can also perform activities simultaneously. Validation using a convolutional neural network (CNN) for PC, HAR, and machine activity recognition (MAR), considering multiclass and multilabel classification, achieved over 90% accuracy in most cases, underscoring the dataset’s robustness and its capacity to tackle a broad spectrum of real-world scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

In the last few years, WiFi Sensing (WS) has gained attention from researchers due to its potential in various types of applications. It mainly consists of using WiFi networks as a sensor system for different situations, taking advantage of the fact that these networks are already deployed in many environments. Concretely, WS has been employed in indoor environments, such as homes, laboratories, or working centers, to develop smart environments, using WiFi channel information to classify states or activities in the surrounding area.

The Channel State Information (CSI) has become the most common data type used in WS to obtain data from environmental changes with WiFi signals. This parameter is estimated in the receiver to recover the transmitted WiFi signal and provides a large amount of information to characterize the propagation channel at each instant. Therefore, the use of CSI allows the development of detection applications. Some of these applications include human activity recognition (HAR), people counting (PC), people identification (PI), and people tracking (PT)1,2,3,4,5. The goal of these applications is to detect real-world situations with increasing accuracy. To achieve this goal, it is essential to collect various data from a wide range of environments. In response to this need, some researchers have dedicated their efforts to creating various datasets.

Table 1 provides an overview of published datasets intended for CSI-based WS, including their main characteristics, such as application types, number of measurement days, number of different environments, number of involved people, number of people for PC (measured people), number of activities for HAR, number of transmitters and receivers (TX-RX) and WiFi channel bandwidth. The diversity of these datasets has driven the advancement of applications related to human activity, such as HAR6,7,8,9,10,11, PC12,13,14, PI4,15,16,17, PT14,18 and gesture monitoring using different types of signals19,20.

Nevertheless, significant gaps remain. Despite the progress made, most existing datasets focus only on human-related activities and do not consider machine recognition (MR) and machine activity recognition (MAR), even in industrial environments where humans and machines coexist. Machine activity detection differs fundamentally from human activity detection, as the CSI frames exhibit variations in amplitude and phase, which show distinct patterns and other intrinsic characteristics, such as the presence of impulsive noise21.

In addition, only a few datasets contain data from the same activities on different days and scenarios, which are essential for developing new models with cross-domain (CD) capacity5. Cross-domain implies that a model trained with one dataset in one scenario under specific conditions (one domain) can classify correctly under other conditions, mainly other scenarios (other domains).

In this sense, we present EHUNAM dataset22, which is included in the final row of Table 1 and encompasses applications such as HAR, PI, PC, MR, and MAR, the latter two representing a recent and unexplored research area21,23,24. Unlike previously available datasets, EHUNAM provides data collected across three measurement campaigns (MC1, MC2, and MC3), conducted over multiple days and under diverse scenarios, including an industrial environment. This heterogeneity directly supports the development of applications with cross-domain capabilities. Furthermore, it complements and extends existing datasets by offering reliable data for both human activity detection and machine activity recognition. Specifically, the main contributions of EHUNAM are:

-

First, the present dataset contains novel CSI data related to human presence to improve the cross-domain capabilities of deep learning (DL) models. In this sense, the HAR data covers five scenarios of up to eleven activities, four performed by two people simultaneously. Similarly, measurement sets in these five scenarios are included for PC to detect up to eight people. Both HAR and PC data include PI possibilities.

-

Second, we present novel CSI data in an industrial environment that includes MAR and PC applications. In this sense, EHUNAM contains data about the working status of industrial machines and fourteen people on seven measurement sets with several people and machine status combinations simultaneously. Among others, we prove this data allows the detection of machine-with-human-presence, a field of use of WiFi CSIs for safety and efficiency at work yet to be explored.

-

Third, the dataset also contains novel CSI data for small appliance recognition, including measurements in two scenarios on five different days, to improve research about the impact of small machines and engines in indoor environments on CSI data and detection capacities, even when multiple devices are operating concurrently.

-

In addition, diversity in data collection is essential for transferability and CD. The setup includes two network interface cards (NICs), Broadcom and Atheros, together with two software tools, Nexmon CSI Extraction (NCE) and Atheros CSI Tool (ACT), to collect CSI data with bandwidths of 20 and 80 MHz. Three transmission methods were used for data collection: FTP, Iperf3, and HT-sounding packets; moreover, up to four receivers operated simultaneously in the same measurement.

-

Finally, the EHUNAM dataset results from three extensive measurement campaigns, covering approximately 38 hours of recordings over 23 days, involving 21 people, nine machines, and eight scenarios. This comprehensive collection provides diverse research to improve WS and CD capabilities.

Previous research has employed parts of the dataset presented in this paper to explore various applications. In particular, these studies discuss using CSI in human activity recognition, machine recognition through detecting impulsive noise sources, and human presence detection (HPD) and people counting in industrial environments. The first paper25 focuses on HAR and PC, using MC1 measures for cross-domain with few-shot learning, achieving accuracies above 80% in both cases. The second23 and third21 papers investigate the identification of home appliances as sources of impulsive noise, in which all MC2 measurements are employed to achieve results above 85% accuracy, including multilabel and cross-domain capabilities. Most recently, a study24 employed MC3 measurements to detect human presence with 99% accuracy and to perform people counting with 92% accuracy in the industrial environment with machine activity.

Methods

This paper presents a comprehensive WiFi CSI-based dataset, so a brief overview of CSI is appropriate. The CSIs represent the Channel Frequency Response (CFR) and show the state of the communication link in WiFi systems with Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiplexing (OFDM) technologies. In this sense, the CSI provides information on the amplitude and phase of the radiofrequency channel for each OFDM subcarrier at the receiver. The CSI of an OFDM signal with S subcarriers is:

where Hs is the value of CSI for the s-th subcarrier and can be written as:

representing ∣Hs∣ the amplitude, and φs the phase. Being Xs and Ys transmitted and received signals at the s-th subcarrier respectively, then:

where N represents the complex additive white Gaussian noise of the communication channel.

Regarding measurements, the complete dataset is formed by three measurement campaigns (MC), which covered 23 days. Each MC has its own characteristics in terms of data records and applications, with a variety of specifications that contribute to quantitatively enriching the dataset. The main data records characteristics for each MC can be seen in Table 2, while Table 3 shows its applications for multiclass and multilabel classification.

This dataset22 was collected as part of a study reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research and Teaching of the Faculty of Engineering at UNAM (the National Autonomous University of Mexico; Application Number: CEID-FI 2025-PI001). All participants were informed about the purpose of the study and provided written consent for the collection and publication of all data, including phenotypic information such as age, weight, height, and gender. The three measurement campaigns are described in detail below:

Measurement Campaign 1

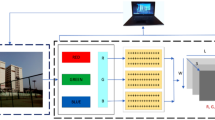

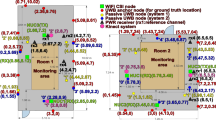

The MC1 were conducted over seven days in five distinct environments or scenarios: an empty basement room (Fig. 2a), a classroom (Fig. 2b), an office (Fig. 2c), a storage room (Fig. 2d) and a laboratory (Fig. 2e). In all scenarios of the MC1 campaign, the measurement system (Fig. 1) remains consistent and includes a router, a switch, two laptops, and between four and five Raspberry Pi 4 devices. The router is configured as a WiFi access point (AP). One Raspberry Pi 4 acts as the transmitter, while the remaining units (three in the basement room and four in the other scenarios) serve as receivers. One laptop, connected to the AP, generates traffic from the transmitter by downloading a file. The second laptop, connected to the switch and to all receivers via Ethernet, centrally controls the CSI packet capture.

The measurements in the basement room were performed twice on two different days, with the position of the transmitter Raspberry Pi 4 changed each day, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. Photographs of the experimental scenarios for MC1 are shown in Fig. 3.

The tools used in the traffic generation process were FTP (File Transfer Protocol) and Iperf3. The WiFi standard used was IEEE 802.11 n/ac, and Nexmon CSI Extractor (NCE) was the data capture tool. The NCE tool is designed to extract CSI from frames modulated with the IEEE 802.11a/g/n/ac WiFi standards. It is compatible with select chipsets, including the Broadcom chipset BCM43455C0, which is the one utilized in the Raspberry Pi 3B+/426,27.

Each CSI measurement was 60 seconds long. Measurements were captured at 20 and 80 MHz bandwidths (BW), with 64 and 256 OFDM subcarriers, respectively. The 5 GHz band was used in channel 40. Generally, CSI frame acquisition is not uniform in time due to the burst traffic used by WiFi. Therefore, 20 MHz BW measurements were generated in a way that ensured the CSI frames were temporally equispaced. The interval between frames was set at 50 and 100 ms.

Applications

The measurements associated with the MC1 sets (Table 4) can initially be utilized in three applications: HAR, PC, and PI. The participants were two women and six men aged 29–60 years, and all people were instructed to perform naturally.

Concerning HAR, the following activities were performed over the scenarios: in the measurements carried out in the basement room, laboratory, and storage room, participants performed the following activities individually and consecutively for 60 seconds: jumping (J), walking (W), and standing (S). In the measures taken in the office and classroom, the person’s activities were W, J, S, sitting (T), sitting down and getting up (G), and falling (F). In addition, two people were involved in activities simultaneously to generate multilabel records in these two scenarios.

The explanation of each activity is as follows. In J, the person jumped at the point indicated by the person icon in Fig. 2. In W, the person walked around the indicated point. In S, the person remained standing in the same place. In T, the person remained seated. In G, the person alternated between sitting and standing, and, finally, in F, the person dropped onto an inflatable mattress placed at ground level and stood up repeatedly. In the multilabel classification, one person walked while another person performed another activity: G, S, T, or F.

Related to the PC, the number of individuals can vary depending on the scenario, with a maximum of four or eight participants. In the four-person measurements, five individuals participate, with all but one starting by walking freely around the room while the remaining individual waits outside. One person leaves the room every minute, and the order in which participants leave varies from measurement to measurement. The number of people recorded in each session gradually decreases from the initial group size to zero, ensuring that each combination of participants is unique and never repeated. The same rules are followed for the eight-person measurements.

About PI, it can be used in both HAR and PC measurements because each participant is identified. In all scenarios, measurements were collected in the absence of people in the area, and these measurements are referred to as E.

Table 4 shows the details of the measurements related to the applications above. It shows the name assigned to each MC1 set and the environment where the measurement was taken. The letter A or B in the MC1 Set column indicates the BW of the measurements when two BW were used, where A corresponds to 20 MHz, and B to 80 MHz. If there is no letter, the BW, by default, is 80MHz. In the People column, each letter corresponds to a person identifier. The Multiclass column is associated with PC and HAR, specifying the number of people or activities that can be monitored each day. The Multilabel column indicates the datasets that allow the ability to work with measurements of more than one activity at a time.

Measurement Campaign 2

The MC2 was conducted in two scenarios: an office (Office 2 in Fig. 4a) and a meeting room (Fig. 4b). The CSI acquisition tool was the Atheros CSI Tool (ACT), configured on a desktop PC with NIC Qualcomm Atheros QCWB335 for transmission and a laptop with NIC Qualcomm Atheros AR5822 in the reception. The ACT, created by the Wireless and Networked Distributed Sensing (WANDS) research group, is an open-source platform for conducting measurements and experiments on IEEE 802.11n networks. This tool provides access to detailed physical layer (PHY) data from Atheros WiFi NICs, including CSI28. In our case, the transmitter and the receiver worked in access point-client mode. The WiFi standard was 802.11n with 20 MHz bandwidth on channel 11, and unlike the 20 MHz systems with NCE, when we use ACT for this bandwidth, the number of subcarriers is 56 instead of 64. The MR measurements are configured with the number of CSI frames to be sent; in this case, the transmission was 50000, and the reception varied between 45000 and 49000 CSI due to frame losses. Figure 5 shows images of the scenarios.

Applications

MC2 is the set family (Table 5) designed exclusively for home appliance detection analysis, and its measurements allow for MR, including multiclass and multilabel classification. The sets related to MR are one of the novel contributions of this work. The data were also intended for cross-domain generalization of home appliance detection with both multiclass and multilabel classification.

Table 5 shows the information of each MR set. In the Multiclass column, measurements of each device in stand-alone working mode and measurements with the units turned off (i.e., E mode) are included. The Multilabel column reflects the combinations of two or three devices operating simultaneously.

Measurement Campaign 3

The sets associated with MC3 (Table 6) represent additional contributions to the aforementioned dataset and were obtained from measurements carried out over eight non-consecutive days in the Laboratory of Mechanical Design and Advanced Manufacturing of the Institute of Engineering at the UNAM; a facility equipped with industrial machinery such as horizontal and vertical lathes, milling machines, drill presses, and cutting saws, in addition to workbenches for manual operations. The laboratory features a reinforced concrete ceiling, brick walls, and a layout organized into parallel rows of machines separated by clearly marked walkways, ensuring both accessibility and safety. This physical configuration, combining large metallic equipment and human activity, constitutes a representative industrial scenario where static and dynamic elements interact and influence wireless signal propagation, making it an appropriate environment for the measurements reported in this study.

In our measurements, four horizontal lathes and one manually operated milling machine were used as part of the equipment located in the designated measurement area. The remaining machines were kept turned off throughout the experiments and can therefore be considered as static obstacles (Figs. 6 and 7). In this environment, the measurement setup remained consistent with the configuration described previously (Fig. 1). Each CSI measurement was conducted for 60 seconds. Measurements were performed in the 2.4 GHz band on channel 13 with a bandwidth of 20 MHz and in the 5 GHz band on channel 40 with an 80 MHz bandwidth, as shown in Table 2. The CSI was extracted using the NCE with the WiFi standard 802.11 n/ac.

The measurements collected in the industrial environment are grouped into three main applications: people counting (PC), detection of machine operating states (machine activity recognition), and multilabel situations in which human presence and machine activity coincide. These categories include variations in the number of people present, different machine operating states, and configurations where both phenomena take place concurrently. For the machine-related measurements, data collection focused on CSI recordings under three conditions: when the machines were simply powered on, when they were operating, and when an operator was engaged in the fabrication of a workpiece while remaining mostly static, with movement limited primarily to the hands and torso.

Applications

The MC3 sets include measurements for multiclass classification, where PC and MAR are captured independently, as well as for multilabel classification, where multiple machine and human activities are performed simultaneously during data acquisition, as one can observe in Table 6.

PC sets have measurements from six different days, and the number of people in every set varies between one and three. The study involved seven subjects, two women and five men. People walked around the measurement area naturally. On the other hand, MAR consists of measurements of an industrial lathe (Machine 5) in two operating states: machine on (O) and running (R). O means the motor is powered but not engaged, and R is when the motor is engaged. Concerning PI, as in MC1, it can be used in PC and multilabel PC+MAR measurements due to each participant being identified.

In the context of multilabel scenarios, some examples of configurations are a single machine operated by a man and two machines operated by one man each of them. The remaining configurations are described in complete sentences in the multilabel column of Table 6 to facilitate comprehension. The previously mentioned E state was also measured in this context, where the machines are off, and there are no people in the area. Five machines and 14 people were involved. The machines were four horizontal lathes and a manual milling cutter machine. The people involved during the multilabel measurements were two women and twelve men.

Data Records

The dataset has been deposited in a Figshare repository22, where it can be accessed and downloaded. As previously mentioned, the dataset is organized into three measurement campaigns: MC1, MC2, and MC3. A total of 2,401 measurements are included, which are categorized as follows: 1618 measurements are attributed to MC1, encompassing a total duration of 27 hours; 105 measurements are associated with MC2, where data transmission is configured based on the number of packets sent, resulting in approximately 22 minutes of measurements; and 678 measurements are ascribed to MC3, with a total duration of 11 hours. The number of CSIs per 60-second measurement varies between 1K and 100K, depending on the channel bandwidth and reception conditions. The median value of CSI per measure is 58K. In the MC1_01A and MC1_02A sets, where CSIs are equispaced in time, the number of CSIs ranges from 0.6K to 1.2K.

This dataset is provided in a single .zip file, which, once downloaded and unzipped, contains individual .mat files for each measurement. Each .mat file comprises multiple variables, which serve as structured containers for different types of data, including the complex-valued CSI measurements and supplementary metadata to identify and facilitate their use by other researchers. The structure of each file is as follows (in alphabetical order):

-

Activity: corresponds to the activities performed in each measurement. Specifically, walking (W), standing still (S), jumping (J), sitting still (T), sitting down and getting up (G), and falling (F), which are listed in Table 8. The label empty (E) is included, although it refers specifically to measurements in which there is no human or machine activity.

-

Application: these are identifiers of the possible applications of the measurements. PC for people counting, HAR for human activity recognition, MR for appliance machine recognition, MAR for machine activity recognition, and PC+MAR for people counting and machine recognition simultaneously.

-

Band: the frequency band used for WiFi communications. The bands are 2.4 and 5 GHz.

-

BW: corresponds to the bandwidth associated with each measurement, 20 and 80 MHz.

-

Channel: are the channels used to realize the capture of data. The channels are 11, 13, and 40.

-

CSI: represented the complex-valued CSI matrix for each measure.

-

CSI_Extractor: refers to the software used to capture the CSIs. NCE for Nexmon CSI Extractor and ACT for Atheros CSI Tools.

-

Date: is the date when each measurement was carried out.

-

Environment: is the location where the measurement was performed. The locations are the basement room, laboratory, storage room, office 1, classroom, office 2, meeting room, and industrial laboratory as shown in Figs. 2, 4, and 6.

-

Machine: corresponds to the machine identifiers associated with each measure. The values range from 1 to 9 as seen in Table 8.

-

N_Files: number of files in each set. For example, all measurements of MC1_04 exhibit the same value for this variable, in this case 174.

-

N_Machine: total number of machines involved in the measure.

-

N_People: total number of people involved in the measure.

-

N_Rx: number of receivers. Three or four in MC1, one in MC2, and three in MC3.

-

NIC: models of the network interface cards of the CSI receivers as applicable in each case.

-

Number: is a numerical identifier to differentiate measurements when all the previous fields are equal. For example, this identifier is the way to distinguish between different measurements of the E class taken in the same environment.

-

Occupied_SC: number of useful subcarriers (data+pilots) to be processed. Null subcarriers were excluded according to 802.11n/ac standards, and our data analysis.

-

People: includes the identifiers of each person in the measurements.They range from the lowercase letter “a” to “u”, for 21 people. Table 7 reports gender, age, height, and weight for 17 of the 21 participants, which we consider useful for PI applications. These data were self-reported by the participants, who were informed of their intended use.

-

RSSI: is the RSSI (Received Signal Strength Indicator) vector, corresponding to the power value of the received signal per CSI, expressed in dBm.

-

Rx: corresponds to the receiver identifier. The Raspberries used in MC1 are up to four (1-4), in MC3 are three (1-3), and one laptop for MC2 (1).

-

Set: Contains the name of the set following the names in the Tables 4, 5, and 6, which includes its MC. For example, MC1_01A.

-

Standard: is the WiFi standard for the implemented measurement system. These can be IEEE 802.11n and 802.11ac.

-

Status: corresponds to the machine state at the measurement time. The machines can be on (O) or running (R).

-

Subcarriers: number of OFDM subcarriers captured by the CSI acquisition software. For MC1 and MC3, 64 subcarriers were used for 20 MHz measurements and 256 for 80 MHz bandwidth measurements. The number of subcarriers used in all MC2 sets is 56.

-

T_Meas: refers to the duration of each captured CSI measurement in seconds.

-

Time: The precise moment (expressed in hours, minutes, and seconds) at which each measurement was recorded.

-

Timestamp: it is the time difference in milliseconds between each CSI received.

-

Traffic: is the transmission protocol to generate the traffic between TX and RX, i.e., FTP, Iperf3, and high-throughput (HT)-sounding packet. Although an HT-sounding packet is not strictly a protocol, it is a data packet used in ACT with the WiFi 802.11n standard for channel estimation between TX and RX.

During the measurements, receivers could be under conditions of poor reception quality. In that case, due to different reception problems, the number of captured CSIs could be significantly reduced and, therefore, useless for model training purposes. A few files have been removed from the dataset when the number of captured CSIs has been too small (<400 CSIs). As a result, the Number variable may not follow a consecutive numerical sequence in some cases, indicating that measurements at that receiver have been discarded.

All the files include the metadata variables described above; those irrelevant to a file are not assigned a value. For example, the data from MC1 do not have associated machine or status information.

Data File Name

In the previous section, we described the information contained in each of the variables within the .mat files, which constitute the format in which our dataset is provided. In this section, we explain the information encoded in the file names, which is relevant as it provides important details for any classifier automation process. The file name is composed of nine fields separated by lower bar signs (“_”). The first four fields and the ninth one are always meaningful; fields 5 to 8 could have meaning or not, depending on the application. If they are meaningless, they are filled with a “#” sign. Most of the fields have a corresponding variable stored in the .mat file with the same value, which is empty if the field is meaningless.

-

Field 1_Campaign: MC1, MC2 or MC3.

-

Field 2_Set: Two-digit number plus an optional capital letter (“A” or “B”). Sequential number to distinguish the sets within a measurement campaign. If two bandwidths were used in the same measurement campaign, the letter A is added for 20 MHz or B for 80 MHz. If the capital letter is not present, the bandwidth is 80MHz. Variables “Set” and “BW” of the .mat file correspond to the combination of fields 1 and 2.

-

Field 3_Receiver: This field contains a one-digit number (1-4) indicating the receiver that recorded the measurement. The variable is “Rx.”

-

Field 4_Application: HAR, PC, MR, MAR, PCMAR, E. Variable “Application”.

-

Field 5_People: One small letter for each person participating in the measurement (“a” to “u”). Notice that the length of this field is the number of people present during the measurement. Variable “People” and N_People.

-

Field 6_Activity: One capital letter to identify the activity performed during the measurement. See Table 8. Variable “Activity”.

-

Field 7_Machine: One-digit number to identify the machine(s) running in the measurement. See Table 8 of the paper. Variable “Machine”.

-

Field 8_Status: One capital letter (“O” or “R”) that indicates whether the machine was ON but not running (“O”) or it was ON and running (“R”). Variable “Status”.

-

Field 9_Sequential number: Two-digit number used to distinguish measurements that have the rest of the fields identical. As most of the measurements are unique, this field is “01” in most cases, but for example, the empty measurements (Application=“E”) were repeated several times, so this field is used to distinguish them. Variable “Number”.

Examples:

-

MC1_01A_1_HAR_e_J_#_#_01.mat: This file corresponds to the first set of MC1 (measurement campaign 1). The signal has a 20 MHz bandwidth. It was recorded with receiver 1. It is intended to be used for human activity recognition (“HAR”). In this case, the person “e” was jumping (“J”). As there are no machines involved, the fields Machine and Status are meaningless and are filled with “#”. There is only one measurement of this kind, so the last field is “01”.

-

MC1_06_2_PC_abf_#_#_#_01.mat: This file corresponds to the sixth set of MC1. The signal has an 80 MHz bandwidth. It was recorded with receiver 2. It is intended for people counting (“PC”). In this case, three people “a”, “b”, and “f” were present during the measurement. The following three fields are meaningless and are filled with “#”. There is only one measurement of this kind so the last field is “01”.

-

MC1_05_4_E_#_#_#_#_02.mat: This file corresponds to the fifth set of MC1. The signal has an 80 MHz bandwidth. It was recorded with receiver 4. It was recorded with the room empty, so the next four fields are meaningless and are filled with “#”. There are several measurements performed in the empty room. The last field indicates that this is the second one.

-

MC3_01A_2_PCMAR_j_#_8_R_01.mat: This file corresponds to the first set of MC3. The signal has a 20 MHz bandwidth and was recorded with receiver 2. It is intended to be used for human and machine activity recognition (“PC+MAR”). In this case, the person “j” was present during the measurement, and machine eight was running. There is only one measurement of this kind, so the last field is “01.”

Technical Validation

Data analysis and Preprocessing

The validation process performs an in-depth examination of the datasets. The CSI is a complex-valued vector as in Equation (1) with 56, 64, or 256 subcarriers, depending on the BW (20 MHz or 80 MHz) and the acquisition software (ACT measurements contain 56 subcarriers, while NCE measurements contain 64 for 20 MHz). The number of CSI measurements depends on factors such as the acquisition software used, the duration of the measurement, the environmental conditions, and the level of spectrum occupation.

In the preprocessing of the measurements, the pilot, null, and data subcarriers of each measurement are analyzed according to the IEEE 802.11n/ac standard29 and the bandwidth we use. The null subcarriers, aimed at the protection against interferences and adjacent channels, are eliminated because they do not give information about the propagation channel30. The number of null subcarriers can vary for a given bandwidth depending on the transmission mode29. As illustrated in Table 9, the number of useful subcarriers in 80 MHz differs between MC1 and MC3 due to the utilization of an 80 MHz channel in MC1, as opposed to 4 adjacent channels of 20 MHz in a duplicate non-high-throughput (non-HT) transmission mode in MC3.

In reception, the estimated CSI is affected by errors and offsets due to the noise and synchronization errors in the decoding process. Usually, these errors do not affect communication, but they are relevant in using CSI in sensing applications, especially when working with the phase. The main errors that are introduced in the estimated CSI phase are31,32:

-

Sampling Frequency Offset (SFO): is due to frequency desynchronization between transmitter and receiver, which generates a time lag between the transmitted and received signal.

-

Sampling Time Offset (STO): due to hardware imperfections, during the packet detection process by the receiver, through correlation operations and signal power calculation, introduces a random time offset, which also causes a CSI phase shift.

-

Carrier Frequency Offset (CFO): occurs due to the lack of synchronization at the receiver center frequency.

Starting from Equation (3), we can express the estimated CSI phase at the s-th subcarrier \({\widehat{\varphi }}_{s}\) as:

where φs is the true phase in Equation (2), Δt is the time offset at the receiver, ms is the index of the s-th carrier, β is the random phase offset caused by the CFO, Z represents the measured noise, and P is the size of the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), as specified in IEEE 802.11 standard33.

To reduce the impact of these errors and improve the detection capability, it is necessary to apply preprocessing techniques such as noise removal, redundant value removal, and phase calibration31,32,34,35,36. We used the TSFR Method (Time Smoothing and Frequency Rebuild)36 to process our measurements. This method eliminates phase shifts through a multi-stage preprocessing. First, a linear regression is applied to the data; then, a filtering step is applied in the time domain with the Savitzky-Golay filter; and finally, to eliminate the discontinuities caused in each subcarrier, a phase correction based on thresholds is performed. The Fig. 8 shows the first ten subcarriers of an 80 MHz measurement before and after the application of the TSFR method.

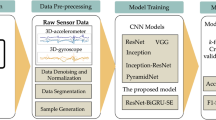

Classification Model

Dataset validation was performed using a deep learning model, specifically a convolutional neural network (CNN) implemented in TensorFlow and Keras. The network follows a sequential architecture with three convolutional layers (32 filters of 5 × 5, 64 filters of 3 × 3, and 128 filters of 3 × 3), two fully connected layers (256 and 128 units). Regularization techniques are employed to enhance performance, including maxpooling, dropout, and flatten layers. The activation function used in the intermediate layers is Mish37, while Softmax is applied in the output layer. The structure of the CNN is illustrated in Fig. 9.

The optimizer used is Adam, with a learning rate of 0.001. The Sparse Categorical Cross-Entropy loss function is employed, and Sparse Categorical Accuracy is used as the performance metric to evaluate the CNN during training and validation. For the batch size, a value of 128 was used for 80 MHz measurements and 256 for 20 MHz measurements. These values were selected because they are common in CNN training and, in our validation process, provided better classification performance.

The input to the CNN model consists of groups of 25 CSIs using both amplitude and phase values, so the input dimensions of the CNN are (S, 25, 2), where S is the number of useful subcarriers in each case as defined in Table 9. It is noteworthy that the amplitude and phase channels are represented by 2 in the third dimension of the input, similar to a two-color image. The training, validation, and test sets were constructed from the same receiver-application pair, with the data divided into 65% for training, 17.5% for validation, and 17.5% for testing.

Data Validation

Classification models are trained with the described CNN for each set, application, and receiver. For instance, MC_01A, which contains measurements for PC and HAR applications from three receivers, undergoes six validation processes: Rx1_PC, Rx2_PC, Rx3_PC, Rx1_HAR, Rx2_HAR, and Rx3_HAR.

Figure 10 presents each set’s average accuracy computed from the individual results of each receiver per application. In the original experiment, accuracy, F1 score, and confusion matrices were obtained. Since the F1 score exhibited a trend closely aligned with accuracy, it is not reported here for the sake of clarity and conciseness. Confusion matrices are presented in Fig. 11, for both multiclass and multilabel classification, providing a more comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance.

As can be seen, data from each set can be classified with high accuracy in most cases. Concretely, MC1 PC results are higher than 65% in all cases except for MC1_01A and MC1_02A, whose consecutive CSIs are temporally equispaced with periods of 100 ms and 50 ms, respectively. The accuracy results for these measurements may be affected by a reduced number of CSIs per measurement, which limits model training and generalization capabilities. These sets serve as a basis for comparative experiments between temporally equispaced and non-equispaced CSIs to investigate thresholds for the minimum number of CSIs needed for detection, and even to calculate Doppler shifts from CSIs.

The results related to MC1 HAR are obtained by training models with sets containing up to 7 activity classes. In four sets (from MC1_01A to MC1_04), the data include 4 classes as shown in Table 4, and in the other two sets (MC1_05 and MC1_06), three additional activities are included, resulting in a total of 7 classes. Figure 10 shows that the accuracy results are higher than 89%, except for the datasets MC1_01A and MC1_02A, which align with the results observed in PC from the earlier analysis.

The MR results of MC2 sets exceed 97% in all cases. Up to 8 classes are trained, including multilabel and multiclass labels, demonstrating promising results for machine detection. The classes include empty, dryer, saw, drill, drill-dryer, drill-saw, saw-dryer, and drill-saw-dryer, according to the information provided in Tables 5 and 8. For MC3, the measurements support PC and MAR applications. The results in PC surpass 90% accuracy in most cases, except for MC3_01A and MC4_01A, which achieve 77.5% and 79% accuracy, respectively. The wide variety of situations encountered in MC3 measurements enables studies with multiple detection targets. In this study, we focus on detecting the different working states of a specific machine (5, horizontal lathe), including whether it is off (E), on (O), running (R), being operated by a person, or working simultaneously with one or two other machines. Validation models are derived from a combination of PC and MAR measurements. The results, presented in Fig. 10 as PC+MAR, show that accuracy exceeds 93% in all cases. These sets demonstrate superior and more stable performance compared to PC.

Figure 11 shows examples of confusion matrices obtained from the three measurement campaigns and the different applications considered. Following the same color scheme used in Fig. 10, matrices (a-c) correspond to the three receivers of MC1_01B for PC, with recordings ranging from 0 to 4 people. Matrices (d-g) belong to MC1_05 and include the four receivers used in this measurement set; in this case, HAR is evaluated, considering jumping (J), walking (W), standing (S), sitting (T), sitting down and getting up (G), falling (F), as well as the empty state (E). In campaign MC2, matrices (h) and (i) correspond to MC2_01 and MC2_01, respectively. Both correspond to MR classification in different environments, using a single receiver per set, and involve home appliances numbered 1 to 4 in Table 8. Finally, matrices (j-l) correspond to the three receivers used in MC3_01B, where the classification involves a multilabel scenario with the categories Empty (E), machine operating (R), machine switched on (O), and machine operating with human presence (R+1P), all recorded on the same machine. Overall, these matrices illustrate the classification performance across diverse applications, with the Empty class consistently achieving the highest accuracy.

At this point, it is important to acknowledge that, despite its breadth and novelty, EHUNAM inevitably presents certain limitations that also open avenues for future datasets. While it encompasses diverse environments and activities, the range of scenarios, participants, and machines cannot fully capture the complexity of real-world industrial and non-industrial conditions. The dataset is also constrained by the number of samples, particularly in the industrial environment, and by the limited scope of machinery and operating states represented. Furthermore, all recordings were carried out under controlled conditions and within a limited time frame, which may not entirely reflect more complex or long-term environmental dynamics.

Even with these constraints, the validation results highlight the robustness and applicability of the dataset. The measurements proved effective across different sets, supporting a wide range of human and machine sensing applications. Validation experiments further confirm that EHUNAM achieves reliable performance, thereby opening the door to studies involving multiple receivers and cross-domain scenarios. Overall, the dataset not only reveals current challenges but also establishes a solid and trustworthy testbed for advancing future research in the field.

Usage Notes

Two summary files accompany the database: Summary.xlsx and Summary.mat. These files contain Excel and Matlab tables in which each row corresponds to a measurement file and includes its associated scalar variables; raw data such as CSI, RSSI, and time stamps are excluded. Instead, the tables report the number of CSI measurements available in each file, thereby facilitating quick inspection of the dataset. To ensure data quality and consistency, all files with fewer than 400 CSI measurements were removed from the database, and the list of deleted files is provided below.:

-

MC1_04_3_E_#_#_#_#_01.mat

-

MC1_04_4_E_#_#_#_#_01.mat

-

MC1_04_3_E_#_#_#_#_02.mat

-

MC1_04_2_E_#_#_#_#_03.mat

-

MC1_04_2_E_#_#_#_#_04.mat

-

MC1_04_2_E_#_#_#_#_05.mat

-

MC1_06_4_HAR_g_S_#_#_01.mat

Data availability

The dataset is available through the Figshare repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28541225.

Code availability

Null subcarrier removal and phase preprocessing were done with MATLAB. The Subcarrier.m function, used for null subcarrier deletion, is made available to the community because it is considered of interest due to its specificity, and can be accessed at the repository: https://github.com/GuillermoDiazSM/EHUNAM-dataset. The data validation through the CNN model has been performed with Tensorflow and Keras using Python 3.11.5.

References

Wang, Z., Guo, B., Yu, Z. & Zhou, X. Wi-Fi CSI-Based Behavior Recognition: From Signals and Actions to Activities. IEEE Commun. Mag. 56, 109–115, https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2018.1700144 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. A research on CSI-based human motion detection in complex scenarios. In IEEE HealthCom 1-6, https://doi.org/10.1109/HealthCom.2017.8210800 (2017).

Qian, K., Wu, C., Yang, Z., Liu, Y. & Jamieson, K. Widar: Decimeter-Level Passive Tracking via Velocity Monitoring with Commodity Wi-Fi. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Symposium on Mobile Ad Hoc Networking and Computing Article 6, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1145/3084041.3084067 (ACM, 2017).

Qian, K. et al. Widar2.0: Passive Human Tracking with a Single Wi-Fi Link. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services 350–361, https://doi.org/10.1145/3210240.3210314 (ACM, 2018).

Liu, J., Liu, H., Chen, Y., Wang, Y. & Wang, C. Wireless Sensing for Human Activity: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 22, 1629–1645, https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2019.2934489 (2020).

Yousefi, S., Narui, H., Dayal, S., Ermon, S. & Valaee, S. A Survey on Behavior Recognition Using WiFi Channel State Information. IEEE Commun. Mag. 55, 98–104, https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2017.1700082 (2017).

Guo, L. et al. WiAR: A Public Dataset for Wifi-Based Activity Recognition. IEEE Access 7, 154935–154945, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2947024 (2019).

Zhuravchak, A., Kapshii, O. & Pournaras, E. Human Activity Recognition based on Wi-Fi CSI Data - A Deep Neural Network Approach. Procedia Comput. Sci. 198, 59–66, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.12.211 (2022).

Forbes, G., Massie, S. & Craw, S. WiFi-based Human Activity Recognition using Raspberry Pi. In 2020 IEEE 32nd International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI) 722-730, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTAI50040.2020.00115 (2020).

Bahadori, N., Ashdown, J. & Restuccia, F. ReWiS: Reliable Wi-Fi Sensing Through Few-Shot Multi-Antenna Multi-Receiver CSI Learning. In 2022 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks (WoWMoM) 50–59, https://doi.org/10.1109/WoWMoM54355.2022.00027 (2022).

Schäfer, J., Barrsiwal, B., Kokhkharova, M., Adil, H. & Liebehenschel, J. Human Activity Recognition Using CSI Information with Nexmon. Appl. Sci. 11, 8860, https://doi.org/10.3390/app11198860 (2021).

Di Domenico, S., De Sanctis, M., Cianca, E. & Bianchi, G. A Trained-once Crowd Counting Method Using Differential WiFi Channel State Information. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Physical Analytics (ACM) 37–42, https://doi.org/10.1145/2935651.2935657 (2016).

Sobron, I., Del Ser, J., Eizmendi, I. & Vélez, M. Device-Free People Counting in IoT Environments: New Insights, Results, and Open Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 5, 4396–4408, https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2018.2806990 (2018).

Bocus, M. J. et al. OPERAnet, a multimodal activity recognition dataset acquired from radio frequency and vision-based sensors. Sci. Data 9, 8860, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01573-2 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. GaitSense: Towards Ubiquitous Gait-Based Human Identification with Wi-Fi. ACM Trans. Sen. Netw. 18, 1, https://doi.org/10.1145/3466638 (2021).

Meneghello, F., Fabbro, N. D., Garlisi, D., Tinnirello, I. & Rossi, M. A CSI Dataset for Wireless Human Sensing on 80 MHz Wi-Fi Channels. IEEE Commun. Mag. 61, 146–152, https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.005.2200720 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. Finding the Missing Data: A BERT-Inspired Approach Against Package Loss in Wireless Sensing. In IEEE INFOCOM 2024 - IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS) 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/INFOCOMWKSHPS61880.2024.10620769 (2024).

Huang, S. et al. WiMANS: A Benchmark Dataset for WiFi-Based Multi-user Activity Sensing. In *Computer Vision - ECCV 2024: 18th European Conference, Milan, Italy, September 29-October 4, 2024, Proceedings, Part XLII*, 72–91, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-72946-1_5 (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2024).

Yang, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhang, G., Zheng, Y. & Chi, G. Widar 3.0: WiFi-based Activity Recognition Dataset. IEEE Dataport https://doi.org/10.21227/7znf-qp86 (2020).

Galdino, I. et al. eHealth CSI: A Wi-Fi CSI Dataset of Human Activities. IEEE Access 11, 71003–71012, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3294429 (2023).

Landa, I., Diaz, G., Sobron, I., Eizmendi, I. & Velez, M. Machinery detection by impulsive noise recognition using WiFi sensing. Pervasive and Mobile Computing 107, 102018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmcj.2025.102018 (2025).

de Armas, E. et al. EHUNAM, a WiFi CSI-based dataset for human and machine sensing. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28541225 (2025).

Landa, I., Díaz, G., Sobrón, I., Eizmendi, I. & Vélez, M. WIP: Impulsive Noise Source Recognition with OFDM-WiFi Signals Based on Channel State Information Using Machine Learning. In 2022 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks (WoWMoM) 157–160, https://doi.org/10.1109/WoWMoM54355.2022.00047 (2022).

de Armas, E., Diaz, G., Sobron, I., Matias, J. M. & Eizmendi, I. WiFi-CSI Sensing for Human Presence and Machine Activity in Industrial Environments. In 2025 IEEE 21st International Conference on Factory Communication Systems (WFCS) 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1109/WFCS63373.2025.11077659 (2025).

Diaz, G., Sobron, I., Eizmendi, I., Landa, I. & Velez, M. Activity Recognition from Channel State Information for Few-Sampled Scenarios. In 2023 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps) 1009–1014, https://doi.org/10.1109/GCWkshps58843.2023.10465069 (2023).

Schulz, M., Wegemer, D. & Hollick, M. Nexmon: The C-based Firmware Patching Framework https://nexmon.org (2017).

Gringoli, F., Schulz, M. Link, J., Hollick, M. Free Your CSI: A Channel State Information Extraction Platform For Modern Wi-Fi Chipsets. In Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop on Wireless Network Testbeds, Experimental Evaluation & Characterization 21–28, https://doi.org/10.1145/3349623.3355477 (2019).

Xie, Y., Li, Z. & Li, M. Precise Power Delay Profiling with Commodity WiFi. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking 53–64, https://doi.org/10.1145/2789168.2790124 (ACM, 2015).

IEEE Standard for Information technology - Telecommunications and information exchange between systems - Local and metropolitan area networks - Specific requirements - Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications - Amendment 4: Enhancements for Very High Throughput for Operation in Bands below 6 GHz. IEEE Std 802.11ac-2013 1–425, https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEESTD.2013.6687187 (2013).

Fard Moshiri, P., Shahbazian, R., Nabati, M. & Ghorashi, S. A. A CSI-Based Human Activity Recognition Using Deep Learning. Sensors 21, 7225, https://doi.org/10.3390/s21217225 (2021).

Tian, Z., Wang, J., Yang, X. & Zhou, M. WiCatch: A Wi-Fi Based Hand Gesture Recognition System. IEEE Access 6, 16911–16923, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2814575 (2018).

Wang, G., Abbasi, A. & Liu, H. Dynamic Phase Calibration Method for CSI-based Indoor Positioning. In 2021 IEEE 11th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC) 0108–0113, https://doi.org/10.1109/CCWC51732.2021.9376003 (2021).

Wang, X., Gao, L. & Mao, S. CSI Phase Fingerprinting for Indoor Localization With a Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 3, 1113–1123, https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2016.2558659 (2016).

Speth, M., Fechtel, S. A., Fock, G. & Meyr, H. Optimum receiver design for wireless broad-band systems using OFDM.I. IEEE Trans. Commun. 47, 1668–1677, https://doi.org/10.1109/26.803501 (1999).

Meneghello, F., Garlisi, D., Fabbro, N. D., Tinnirello, I. & Rossi, M. SHARP: Environment and Person Independent Activity Recognition With Commodity IEEE 802.11 Access Points. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 22, 6160–6175, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMC.2022.3185681 (2023).

Diaz, G. et al. Channel phase processing in wireless networks for human activity recognition. Internet Things 24, 100960, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iot.2023.100960 (2023).

Misra, D. Mish: A Self Regularized Non-Monotonic Activation Function. In Proceedings of the 31st British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC) https://doi.org/10.5244/C.34.191 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the UNAM Engineering Institute, especially the LADIMMA laboratory team, for their support in carrying out the measurement campaigns in industrial environments. They also acknowledge the financial support received from CONAHCYT through student grant No. 928123, the UNAM long-term activity support grants, the UNAM-PAPIIT project IN102025, the Basque Government under grant IT1436-22, and the Spanish Government through the THERESA project (grant PID2021-124706OB-I00, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ERDF, A way of making Europe).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.S., I.E., G.D., I.L., and M.V. were engaged in the design of the experiment, setup of the measurement system, and collection of MC1 measurements. I.L. was in charge of the experiment design, configuration of the measurement system, and collection of MC2 measurements. E.D. and J.M. were in charge of the design of the experiment, the configuration of the measurement system, and the collection of MC3 measurements. The design and programming in Python of the convolutional network used for technical validation was done by G.D. and E.D. The organization and validation of the data was the responsibility of E.D., assisted by I.S. and I.E. The creation of programs in MATLAB for the creation of variables and naming of measurements was done by I.E. The writing of the article was mostly done by E.D., assisted by G.D. The work in the organization and distribution of tasks among the authors to achieve this paper was done by I.S. All authors reviewed the manuscript and made constructive contributions for its publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Armas, E., Diaz, G., Sobron, I. et al. EHUNAM, a WiFi CSI-based dataset for human and machine sensing. Sci Data 12, 1950 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06238-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06238-4