Abstract

Brassica rapa and B. oleracea are two diploid crops of agronomic importance, which display important phenotypic variation. They are the diploid progenitors of B. napus (oilseed rape), another major crop, which suffers from low genetic diversity. For that reason, B. rapa and B. oleracea are often used to introgress traits of interest into B. napus. In this study we assembled, at the chromosome level, the genomes of three B. oleracea accessions (including a wild type), and largely improved the genome assemblies of two B. rapa genotypes using Oxford Nanopore Technologies and Illumina sequencing. A total of 91.9 to 98.7% of the assembled sequences were anchored to pseudochromosomes. We also produced RNA-Seq data from different organs (flower bud, leaf, root and stem) for gene annotations. Overall, 94.97 to 99.49% of the predicted genes are on pseudomolecules. Finally, we also predicted their resistance gene analogs, including ones unique to each assembly. These five chromosome level assemblies represent a crucial resource to expand the known reservoir of disease resistance genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The Brassica genus contains several crop species cultivated as oilseeds, vegetables and condiments. It belongs to the Brassicaceae family, which comprises approximately 4,000 species and 350 genera1,2. B. oleracea and B. rapa are two agronomically important species that are primarily grown as vegetables. These two species diverged from a common ancestor about 4 million years ago. Both species present considerable phenotypic diversity which has been subjected to independent selection, giving rise to numerous morphotypes3,4,5,6. For example, different varieties of B. oleracea account for broccoli, brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower and kale, among others, while B. rapa is grown as Chinese cabbage, pak choi, mizuna and turnip5.

B. oleracea and B. rapa are the diploid progenitors of B. napus, which was formed through their interspecific hybridization and genome doubling7. B. napus, also known as oilseed rape or canola, is one of the most economically important oilseed crops, processed into edible and industrial oil8. However, due to its polyploid origin and extensive human selection, primarily for seed quality traits, its genetic diversity has been severely eroded9. As a result, the diversity present in its parental diploid progenitors is often exploited and introgressed into B. napus to introduce agronomically favorable genes, including disease resistance (R) genes10,11,12,13.

With the recent advent of third-generation sequencing technologies, it is now possible to assemble plant genomes at the chromosome level, facilitating the identification and cloning of genes, including causal R genes, for example for blackleg14,15, clubroot16 and Sclerotinia stem rot17 in Brassica. However, the genome assembly of only a few individuals highlights the inadequacy of single reference genomes in capturing species-wide genetic diversity and therefore the requirement to construct pangenomes. Analysis of the B. oleracea and B. rapa pangenomes revealed that resistance gene analogs (RGAs) are highly affected by presence-absence variation, with 12% and 30%, respectively, forming the variable genomes of B. oleracea and B. rapa18,19. Having multiple genome assemblies which capture the diversity between accessions and morphotypes is therefore crucial in expanding the repertoire of known RGAs which underpins the identification of functional R genes.

Here, we report the construction of high-quality chromosome level genome assemblies for three B. oleracea accessions: B. oleracea ssp. acephala cv. C102, B. oleracea ssp. botrytis cv. Nd125, and a wild type B. oleracea individual ‘Bos01’ from Le Hode (Normandy, France). We also improved the genome assemblies of two previously published B. rapa accessions: B. rapa ssp. narinosa cv. Wutacai4 and B. rapa ssp. trilocularis cv. R50020. When compared with previous versions of the same accession or other accessions of the same morphotype, our assemblies contain, on average, over 13,000 additional gene annotations which include novel RGAs. These assemblies provide a valuable resource for the exploration of novel RGAs which have the potential to contribute toward the improvement of disease resistance in Brassica crops.

Methods

Plant material, DNA extraction, sequencing

One individual of two B. rapa (B. rapa ssp. narinosa cv. Wutacai and B. rapa ssp. trilocularis cv. R500) and three B. oleracea accessions (B. oleracea ssp. acephala cv C102, B. oleracea ssp. botrytis cv Nd125, a wild type B. oleracea ‘Bos01’ individual from Le Hode, Normandy, France) were grown in a greenhouse (16 h of light at 21 °C followed by 8 h of dark at 18 °C). Plants were grown in pots filled with a non fertilized commercial substrate (Falienor, reference 922016F3) and irrigated twice a week with a commercial fertilized solution (Liquoplant Blue, 2.5% nitrogen, 5% phosphorus, 2.5% potassium, w/v). These different accessions were retrieved from the BraCySol Biological Resource Center (https://eng-igepp.rennes.hub.inrae.fr/about-igepp/platforms/bracysol). The collected plant materials were flash frozen and stored at −80 °C. High-quality high-molecular weight (HMW) DNA was generated for each accession from 1 g of young leaves of a single individual using a CTAB extraction followed by a purification using the commercial Qiagen Genomic-tip (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA), as previously described21. HMW gDNA quality was checked on a FemtoPulse system (Agilent), revealing DNA molecules to be over 40 kb. For each accession, a library was prepared using the Native Barcoding Kit 24 V14 - Ligation sequencing gDNA (SQK-NBD114.24). HMW DNA libraries were sequenced on PromethION flow cells. In addition, Illumina DNA sequencing was performed using a NovaSeq 6000 (2*150 paired-end reads). Raw DNA Seq data are available on ENA: PRJEB91561 (B. oleracea ‘Bos01’), PRJEB91565 (B. oleracea cv. C102), PRJEB91569 (B. oleracea cv. Nd125), PRJEB91574 (B. rapa cv. R500), PRJEB91578 (B. rapa cv. Wutacai)22.

De novo assemblies of chromosome level nuclear genomes

The two B. rapa and three B. oleracea nuclear genomes were assembled using the Genoscope GALOP pipeline (https://workflowhub.eu/workflows/1200). Briefly, raw Nanopore reads were assembled using NextDenovo v2.5.1 (Nextomics, https://github.com/Nextomics/NextDenovo). The resulting contigs were first polished with Medaka v1.7.2 (https://github.com/nanoporetech/medaka) using default parameters and Nanopore long reads. These contigs were then further polished with two rounds of Hapo-G v1.123, using Illumina short reads and default parameters. They were finally scaffolded using Ragtag v2.1.024, with either the B. rapa Z1 v225 or the B. oleracea cv. Korso genome26 as the reference, depending on the species. A schematic diagram summarizing the workflow used for de novo assembly of the nuclear genomes is presented in Figure S1.

RNA extraction, sequencing and gene prediction

To aid gene prediction, Illumina RNA-Seq data were obtained for each accession using different organs that were harvested on the same plant (same as the one used for DNA sequencing) at different developmental stages. More precisely, we harvested leaves, roots and stems on plants at the 4–6 leaf stage, and flower buds on mature plants. The different organs were first harvested separately and flash frozen. They were then ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. A similar quantity of powder from the different organs was bulked and used to extract total RNA using the Nucleospin RNA Plus kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany). The cDNA library was constructed using NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, USA) and Illumina paired-end sequencing was performed on a Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Azenta Life Sciences, Germany). Raw RNA Seq data are available on ENA: PRJEB91561 (B. oleracea ‘Bos01’), PRJEB91565 (B. oleracea cv. C102), PRJEB91569 (B. oleracea cv. Nd125), PRJEB91574 (B. rapa cv. R500), PRJEB91578 (B. rapa cv. Wutacai)22.

Gene prediction was performed using several reference proteomes: eight from other B. napus genotypes (Westar, ZS11, Quinta, Zheyou7, No2127, Gangan, Tapidor and Shengli)27; Arabidopsis thaliana (proteome ID: UP000006548); B. rapa cv. Z125; B. oleracea cv. HDEM28; and B. napus cv Darmor-bzh29. Regions of low complexity in the genomic sequences were masked using the DustMasker algorithm (version 1.0.0 from the BLAST + 2.10.0 package)30. Protein sequences were aligned to the genome using a two-step strategy. First, BLAT v3631 was used to rapidly localize putative matches. The best hit and all hits with a score ≥ 90% of the best match were retained. In the second step, alignments were refined using Genewise v2.2.032, which accurately identifies intron-exon boundaries. Alignments were retained if more than 75% of the protein length aligned to the genome. Additionally, RNA-Seq short reads (Illumina) were used for four genomes (R500, Wutacai, C102, and Nd125). Reads were mapped to their respective genomes using HISAT2 v2.2.133 with default parameters. The resulting BAM files were used as an input in StringTie v2.2.334, with the–rf option to indicate the orientation of the RNA-Seq libraries. When multiple transcripts were detected for a gene, the most highly expressed one (based on TPM) was selected. GFF files were derived from StringTie outputs to retain only the most highly expressed transcript and to remove single-exon models.

All transcriptomic and protein alignments were integrated using Gmove (https://f1000research.com/posters/5-681), an evidence-driven gene predictor requiring no training. Gmove constructs a graph where nodes and edges represent putative exons and introns extracted from alignments, then extracts paths consistent with the protein evidence, identifying open reading frames. Predicted gene models with more than 50% Untranslated Transcribed Region (UTR) content and with a coding sequence (CDS) length shorter than 300 nucleotides were discarded. All final gene models were renamed according to the MBGP (Multinational Brassica Genome Project) nomenclature. A schematic diagram summarizing the workflow used for de novo assembly of the nuclear genomes is presented in Figure S2. The annotations of the nuclear genes (.gff, mRNA and protein files) are available on the French recherche.data.gouv repository: https://doi.org/10.57745/D21PQM35 (deposited October 2025).

The quality of the genomes was also evaluated based on their Long Tandem Repeat (LTR) composition using LAI version beta3.236. The LTR annotation was performed with LTR_retriever version 3.0.437, which integrated results from both ltrharvest38 (GenomeTools version 1.6.2, using the following parameters: -minlenltr 100, -maxlenltr 7000, -mintsd 4, -maxtsd 6, -motif TGCA, -motifmis 1, -similar 85, -vic 10, -seed 20, -seqids yes) and LTR_finder39 (parallel version 1.3, with the options -harvest_out and -size 1000000). This process followed the recommandations provided at https://github.com/oushujun/LTR_retriever.

Chloroplast genome assemblies

The Illumina DNA Seq data obtained for each accession were also used to assemble the chloroplast genomes of each accession. This was performed using FastPlast v1.2.940 (https://github.com/mrmckain/Fast-Plast). The chloroplast genome assemblies were annotated using the online version of GeSeq41. These assembled and annotated genomes were then validated visually using Geneious Prime 2022.2.2 and the Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplast genome (NC_000932)42 as a reference. A graphical representation of these different chloroplast genomes was obtained using the online OGDRAW v1.3.1 (https://chlorobox.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/OGDraw.html)43. Genome assemblies are available on ENA: PRJEB91562 (B. oleracea ‘Bos01’), PRJEB91566 (B. oleracea cv. C102, PRJEB91570 (B. oleracea cv. Nd125), PRJEB91575 (B. rapa cv. R500), PRJEB91579 (B. rapa cv. Wutacai)22. The annotations of the chloroplast genes (.gff) are available on the French recherche.data.gouv repository: https://doi.org/10.57745/RLHXJH44 (deposited October 2025).

Data Records

All sequencing data and associated materials are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under project accession number PRJEB9144622. The identifiers for the raw DNA and RNA-Seq data are: PRJEB91561 (B. oleracea ‘Bos01’), PRJEB91565 (B. oleracea cv. C102), PRJEB91569 (B. oleracea cv. Nd125), PRJEB91574 (B. rapa cv. R500), PRJEB91578 (B. rapa cv. Wutacai). The identifiers for the chloroplast genome assemblies are: PRJEB91562 (B. oleracea ‘Bos01’), PRJEB91566 (B. oleracea cv. C102), PRJEB91570 (B. oleracea cv. Nd125), PRJEB91575 (B. rapa cv. R500), PRJEB91579 (B. rapa cv. Wutacai). For each studied genotype, the accessions and their related bioprojects (DNA and RNA-Seq raw data, as well as nuclear and chloroplast genome assemblies) are summarized in Table S1. The annotations of the nuclear (.gff, mRNA and protein fasta files) are available on the French recherche data.gouv repository at https://doi.org/10.57745/D21PQM35 (deposited October 2025). On the same repository, the annotations of the chloroplast (.gff) genomes are available at https://doi.org/10.57745/RLHXJH44 (deposited October 2025).

Technical Validation

Evaluation of the de novo assembled genomes

For all five accessions, we obtained genome assemblies ranging from 563 to 646 Mb and from 373 to 404 Mb in B. oleracea and B. rapa, respectively. Overall, 91.9 to 98.7% of the sequences were anchored to pseudomolecules. For the two B. rapa accessions, for which a nuclear genome assembly was previously published4,20, our assemblies are far more complete than the previous versions (Table 1), as exemplified from the pseudomolecule size. For the B. rapa R500 genome, for which there was a genome assembly at the chromosome level, we used SyRI v1.5.445 to identify the regions that were better assembled in our genome assembly and observed that our updated version was particularly improved in the highly repetitive pericentromeric regions, but also at the beginning of chromosome A01 (Fig. 1). For B. oleracea, we also compared the metrics of our genomes to those obtained in other accessions belonging to the same morphotype (Table 1). The genomes used for these analyses were the following: C-8 v246; Korso v147; 07-DH-33 v1 and W1701 v126; T09 v1, T10 v1, T18 v1, T21 v1 and T25 v148; and W03 v149. For these comparisons, the metrics were not extracted from the original publication (except for R500 as indicated in Table 1) but were rather calculated from the downloaded FASTA files using an internal tool named fastoche (https://github.com/institut-de-genomique/fastoche). For the B. oleracea genomes, 91.9 to 98.7% of the assembled sequences were anchored to pseudochromosomes.

Taking advantage of RNA-Seq data obtained from various organs for each accession, we predicted protein-coding genes, and observed 66,049 to 71,867 and 52,275 to 54,266 protein coding sequences in our B. oleracea and B. rapa genotypes, respectively. Importantly, 94.97 to 99.49% of these predicted genes are anchored on pseudomolecules.

Our five newly assembled nuclear genomes were also validated by launching BUSCO v5.8.250 with the brassicales_odb12 dataset (July 2025), revealing a gene completeness of 99.3 to 99.4%. The high quality of our genome assemblies can also be observed through the values obtained for the LTR Assembly Index (value over 10, as expected for reference quality genomes). There was no score for the first genome assembly of B. rapa cv. R50020 as the total and intact LTR sequence content was too low in this first draft assembly for accurate LAI calculation.

Using the Illumina DNA-Seq data obtained for our five genotypes, we also assembled, annotated, and graphically represented their chloroplast genomes using FastPlast v1.2.840, as well as GeSeq41 and OGDRAW43 online versions (example in Fig. 2). Their size ranged from 153,364 to 153,365 bp and from 153,036 to 153,464 bp in B. oleracea and B. rapa, respectively.

Evaluating and expanding the lists of resistance gene analogs

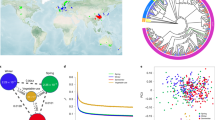

To evaluate the quality of our nuclear genome assemblies and their utility compared to previous versions or assemblies from other accessions belonging to the same morphotype, we explored their RGA content using RGAugury v2.1.7m51. We predicted 1,382 to 1,411 and 1,703 to 1,912 RGAs in our B. rapa and B. oleracea genotypes, respectively (Table 2, see https://doi.org/10.57745/O2FUQ8 for a list of RGA genes identified in each genome). To explore the variability of the RGA content between assemblies, we used OrthoFinder v3.0.152. OrthoFinder analysis identified at least 122 novel RGAs in Nd125, Bos01 and C102, when compared to other accessions from the same morphotype (Table 3, orthogroups from these analyses can been obtained at https://doi.org/10.57745/O2FUQ853). Additionally, over 200 novel RGAs were identified in both Wutacai and R500 (this study) when compared to their previous versions (Table 3, lists of all the unique RGAs for each newly assembled genome are available at https://doi.org/10.57745/O2FUQ853). For the new R500 assembly, we graphically represented using phenogram54 the distribution of the different types of RGAs along each chromosome, allowing the identification of RGA clusters at different chromosomic regions (Fig. 3a). We also only graphically represented the newly identified RGAs in R500, highlighting that these genes are distributed on all chromosomes but are overrepresented at the beginning of chromosome A01 (Fig. 3b), which was not assembled in the previous version (Fig. 1).

The distribution of resistance gene analogs (RGAs) across the new (this study) B. rapa ssp. trilocularis cv. R500 pseudomolecules. The plots includes (a) all RGAs or (b) RGAs that are unique when compared with the previously published20 R500 assembly.

Data availability

All raw DNA and RNA sequencing data are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under project accession number PRJEB91446: PRJEB91561 (B. oleracea ‘Bos01’), PRJEB91565 (B. oleracea cv. C102), PRJEB91569 (B. oleracea cv. Nd125), PRJEB91574 (B. rapa cv. R500), PRJEB91578 (B. rapa cv. Wutacai). The nuclear and chloroplast genomes are also available on ENA: PRJEB91562 (B. oleracea ‘Bos01’), PRJEB91566 (B. oleracea cv. C102, PRJEB91570 (B. oleracea cv. Nd125), PRJEB91575 (B. rapa cv. R500), PRJEB91579 (B. rapa cv. Wutacai). The numbers for the different accessions and their related bioprojects (DNA and RNA-Seq raw data, as well as nuclear and chloroplast genome assemblies) are given in the supplementary Table S1.

The annotations of the nuclear (.gff, mRNA and protein fasta files) are available on the French recherche.data.gouv repository at https://doi.org/10.57745/D21PQM35. On the same repository, the annotations of the chloroplast (.gff) genomes are available at https://doi.org/10.57745/RLHXJH44. We also provided tabular files (https://doi.org/10.57745/O2FUQ853, October 2025) giving: (i) the gene names of the Resistance Gene Analogs identified in all genome assemblies generated in this study and those used for comparisons, (ii) the RGA genes that were unique to our newly assembled genotype compared to others from the same morphotype (B. oleracea cv. C102; B. oleracea cv. Nd125; B. oleracea ‘Bos01’) or from previous genome assemblies (B. rapa cv. R500; B. rapa cv. Wutacai); (iii) the orthologous relationships of RGAs between our newly assembled genotypes and those from the same morphotype or from the previously assembled genome (B. oleracea cv. C102; B. oleracea cv. Nd125; B. oleracea ‘Bos01’; B. rapa cv. R500; B. rapa cv. Wutacai). For all these comparisons, the previously published assembled genomes were the following for B. oleracea: C-8 v246; Korso v147, 07-DH-33 v1 and W1701 v126; T09 v1, T10 v1, T18 v1, T21 v1 and T25 v148; and W03 v149; for B. rapa: Wutacai4, R50020.

Code availability

This study did not produce new codes but rather used publicly available codes. All data analyses were performed using bioinformatic tools. The software versions and used parameters are detailed in the Methods section. When not specified, default parameters were applied.

References

Hendriks, K. P. et al. Global Brassicaceae phylogeny based on filtering of 1,000-gene dataset. Curr. Biol. 33, 4052–4068.e6, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982223010692 (2023).

Nikolov, L. A. et al. Resolving the backbone of the Brassicaceae phylogeny for investigating trait diversity. New Phytol. 222, 1638–1651, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15732 (2019).

Cai, C., Bucher, J., Bakker, F. T. & Bonnema, G. Evidence for two domestication lineages supporting a middle-eastern origin for Brassica oleracea crops from diversified kale populations. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac033, https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhac033 (2022).

Cai, X. et al. Impacts of allopolyploidization and structural variation on intraspecific diversification in Brassica rapa. Genome Biol. 22, 166, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-021-02383-2 (2021).

Cheng, F. et al. Genome resequencing and comparative variome analysis in a Brassica rapa and Brassica oleracea collection. Sci. Data 3, 160119, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.119 (2016).

Qi, X. et al. Genes derived from ancient polyploidy have higher genetic diversity and are associated with domestication in Brassica rapa. New Phytol. 230, 372–386, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17194 (2021).

Nagaharu, U. Genome analysis in brassica with special reference to the experimental formation of B. napus and peculiar mode of fertilization. Japanese Journal of Botany 389–452 (1935).

Raboanatahiry, N., Li, H., Yu, L. & Li, M. Rapeseed (Brassica napus): Processing, Utilization, and Genetic Improvement. Agronomy 11 (2021).

Snowdon, R. J., Abbadi, A., Kox, T., Schmutzer, T. & Leckband, G. Heterotic Haplotype Capture: precision breeding for hybrid performance. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 410–413, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2015.04.013 (2015).

Yu, F., Lydiate, D. J., Gugel, R. K., Sharpe, A. G. & Rimmer, S. R. Introgression of Brassica rapa subsp. sylvestris blackleg resistance into B. napus. Mol. Breed. 30, 1495–1506, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-012-9735-6 (2012).

Yu, F., Lydiate, D. J. & Rimmer, S. R. Identification of two novel genes for blackleg resistance in Brassica napus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 110, 969–979, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-004-1919-y (2005).

Mei, J. et al. Introgression and pyramiding of genetic loci from wild Brassica oleracea into B. napus for improving Sclerotinia resistance of rapeseed. Theor. Appl. Genet. 133, 1313–1319, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-020-03552-w (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Introgression of clubroot resistance from Brassica oleracea into B. napus by interspecific cross. Can. J. Plant Sci., https://doi.org/10.1139/cjps-2024-0242 (2025).

Larkan, N. J. et al. The Brassica napus wall-associated kinase-like (WAKL) gene Rlm9 provides race-specific blackleg resistance. Plant J. 104, 892–900, https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.14966 (2020).

Haddadi, P. et al. Brassica napus genes Rlm4 and Rlm7, conferring resistance to Leptosphaeria maculans, are alleles of the Rlm9 wall-associated kinase-like resistance locus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 20, 1229–1231, https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13818 (2022).

Yang, S. et al. A chromosome-level reference genome facilitates the discovery of clubroot-resistant gene Crr5 in Chinese cabbage. Hortic. Res. 12, uhae338, https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhae338 (2025).

Yang, C. et al. LRR Receptor-like Protein in Rapeseed Confers Resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Infection via a Conserved SsNEP2 Peptide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26 (2025).

Bayer, P. E. et al. Variation in abundance of predicted resistance genes in the Brassica oleracea pangenome. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 789–800, https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13015 (2019).

Amas, J. C. et al. Comparative pangenome analyses provide insights into the evolution of Brassica rapa resistance gene analogues (RGAs). Plant Biotechnol. J. 21, 2100–2112, https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.14116 (2023).

Lou, P. et al. Genetic and genomic resources to study natural variation in Brassica rapa. Plant Direct 4, e00285, https://doi.org/10.1002/pld3.285 (2020).

Vacherie, B., Labadie, K. & Falentin, C. HMW DNA extraction for Long Read Sequencing using CTAB. protocols.io, https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bp2l694yzlqe/v1 (2022).

ENA European Nucleotide Archive https://identifiers.org/ena.embl:PRJEB91446 (2025).

Aury, J.-M. & Istace, B. Hapo-G, haplotype-aware polishing of genome assemblies with accurate reads. NAR Genomics Bioinforma. 3, lqab034, https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/lqab034 (2021).

Alonge, M. et al. Automated assembly scaffolding using RagTag elevates a new tomato system for high-throughput genome editing. Genome Biol. 23, 258, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-022-02823-7 (2022).

Istace, B. et al. Sequencing and Chromosome-Scale Assembly of Plant Genomes, Brassica rapa as a Use Case. Biology 10 (2021).

Guo, N. et al. A graph-based pan-genome of Brassica oleracea provides new insights into its domestication and morphotype diversification. Plant Commun. 5, 100791, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590346223003498 (2024).

Song, J.-M. et al. Eight high-quality genomes reveal pan-genome architecture and ecotype differentiation of Brassica napus. Nat. Plants 6, 34–45, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0577-7 (2020).

Belser, C. et al. Chromosome-scale assemblies of plant genomes using nanopore long reads and optical maps. Nat. Plants 4, 879–887, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-018-0289-4 (2018).

Rousseau-Gueutin, M. et al. Long-read assembly of the Brassica napus reference genome Darmor-bzh. GigaScience 9, giaa137, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa137 (2020).

Morgulis, A., Gertz, E. M., Schäffer, A. A. & Agarwala, R. A Fast and Symmetric DUST Implementation to Mask Low-Complexity DNA Sequences. J. Comput. Biol. 13, 1028–1040, https://doi.org/10.1089/cmb.2006.13.1028. Accessed 8 July 2025 (2006).

Kent, W. J. BLAT—The BLAST-Like Alignment Tool. Genome Res. 12, 656–664, http://genome.cshlp.org/content/12/4/656.abstract (2002).

Birney, E., Clamp, M. & Durbin, R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 14, 988–995, http://genome.cshlp.org/content/14/5/988.abstract (2004).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3122 (2015).

Recherche.data.gouv: https://doi.org/10.57745/D21PQM (2025).

Ou, S., Chen, J. & Jiang, N. Assessing genome assembly quality using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI). Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e126–e126, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky730 (2018).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: A Highly Accurate and Sensitive Program for Identification of Long Terminal Repeat Retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.01310 (2018).

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 18, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-18 (2008).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–W268, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm286 (2007).

McKain, M. R. & Wilson, M. Fast-Plast: rapid de novo assembly and finishing for whole chloroplast genomes. https://github.com/mrmckain/Fast-Plast (2017).

Tillich, M. et al. GeSeq – versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W6–W11, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx391 (2017).

Sato, S., Nakamura, Y., Kaneko, T., Asamizu, E. & Tabata, S. Complete Structure of the Chloroplast Genome of Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 6, 283–290, https://doi.org/10.1093/dnares/6.5.283 (1999).

Greiner, S., Lehwark, P. & Bock, R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W59–W64, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz238 (2019).

Recherche.data.gouv: https://doi.org/10.57745/RLHXJH (2025).

Goel, M., Sun, H., Jiao, W.-B. & Schneeberger, K. SyRI: finding genomic rearrangements and local sequence differences from whole-genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 20, 277, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1911-0 (2019).

Chen, R. et al. Genomic analyses reveal the stepwise domestication and genetic mechanism of curd biogenesis in cauliflower. Nat. Genet. 56, 1235–1244, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-024-01744-4 (2024).

Guo, N. et al. Genome sequencing sheds light on the contribution of structural variants to Brassica oleracea diversification. BMC Biol. 19, 93, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-021-01031-2 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Large-scale gene expression alterations introduced by structural variation drive morphotype diversification in Brassica oleracea. Nat. Genet. 56, 517–529, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-024-01655-4 (2024).

Ji, G. et al. A new chromosome-scale genome of wild Brassica oleracea provides insights into the domestication of Brassica crops. J. Exp. Bot. 75, 2882–2899, https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erae079 (2024).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 (2015).

Li, P. et al. RGAugury: a pipeline for genome-wide prediction of resistance gene analogs (RGAs) in plants. BMC Genomics 17, 852, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-3197-x (2016).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y (2019).

Recherche.data.gouv: https://doi.org/10.57745/O2FUQ8 (2025).

Wolfe, D., Dudek, S., Ritchie, M. D. & Pendergrass, S. A. Visualizing genomic information across chromosomes with PhenoGram. BioData Min. 6, 18, https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0381-6-18 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work has been granted by Plant2Pro® Carnot Institute in the frame of its 2020 call for projects (BRASSIMET). Plant2Pro® is supported by ANR (agreement #20-CARN-024-01). This study was also supported by the Genoscope, the Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique et aux Energies Alternatives (CEA), and France Génomique (ANR-10-INBS-09-08). W. J. W. Thomas benefited from a University of Western Australia Research Collaboration Award to participate in this study. Some sequencing data were obtained from INRAE fundings through a TSARA initiative. The authors thank the Genetic Resource Center BrACySol (INRAE, Ploudaniel, France, https://eng-igepp.rennes.hub.inrae.fr/about-igepp/platforms/bracysol) for providing seeds of the sequenced accessions. We also thank all the staff who took care of our plant material (especially A. Carillot, L. Charlon, J.-P. Constantin, and F. Letertre), as well as the members of the GOGEPP team and GenOuest bioinformatic platform (Rennes, France, https://www.genouest.org/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Rousseau-Gueutin, J.M. Aury, C. Falentin, A. Gravot, and P. Le Boulch conceived the study. C. Falentin and G. Deniot prepared the plant material and performed the RNA and HMW DNA extractions. C. Cruaud and K. Labadie prepared the DNA libraries and took care of the ONT and Illumina sequencing. J.-M. Aury performed the nuclear genome assembly. J-M. Aury performed the gene annotation. C. Falentin, W.J.W. Thomas, M. Rousseau-Gueutin validated the genome assemblies by performing comparative genomic analyses. F. Legeai calculated the LTR Assembly Index. M. Boudet, F. Legeai, W.J.W. Thomas, M. Rousseau-Gueutin, and J. Batley identified the resistance gene analogs and compared their content between accessions. M. Boudet, A. Bourdais and L. Maillet assembled the chloroplast genomes. G. Deniot, C. Falentin and M. Rousseau-Gueutin performed the chloroplast gene annotation and visually validated the chloroplast genome assemblies/annotations. W.J.W. Thomas, M. Rousseau-Gueutin, C. Falentin, and J.-M. Aury wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Falentin, C., Thomas, W.J.W., Boudet, M. et al. Chromosome level assembly of five Brassica rapa and oleracea accessions expand the resistance genes reservoir. Sci Data 12, 2016 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06261-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06261-5