Abstract

Accurate mapping of complete landscape gradients is critical to understanding the evolution patterns and landscape structure of socio-natural ecosystems. However, existing datasets focus primarily on the delineation of urban and rural settlements, neglecting the functional attributes of the landscape and neglecting the two gradients of suburban and natural. Therefore, we fused impervious surface and cultivated land data and used morphological spatial pattern analysis (MSPA) to produce a set of year-by-year urban-suburban-rural-natural (USRN) landscape data, and verified the accuracy with the published data. The spatiotemporal accuracy assessment showed that the USRN data had an average R2 higher than 0.8 with other city-wide products and was superior in spatial integrity to a reference dataset integrating three different data sources. The R2 of suburban versus socio-economic data is lower than that of urban, confirming spatial heterogeneity of suburban landscapes; natural landscapes have higher consistency with nature reserves. USRN expands on the traditional urban-rural binary structure, helps us assess sustainability goals more carefully and provides a sustained and systematic understanding of landscape dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

A landscape is a regional complex with specific structures and functions formed by the interaction of natural and human elements. Landscape elements are the basic units that constitute the Earth’s surface system1. The landscape gradients formed by the coupling of different landscape elements run through the entire social-natural ecosystem2. Since the beginning of the Anthropocene, rapid global urbanization has profoundly altered the landscape structure of the planet. Human activities have had a profound impact on the environment, driving unprecedented changes in land use, ecosystems and socio-natural ecosystems3,4. Urban areas are concentrated areas of human activities and play a vital role in the overall social-ecological system5,6,7,8. But urban ecosystems alone are not enough to help us understand the evolutionary path of the entire social-natural ecosystem. The whole earth surface ecosystem, under the interaction of human factors and natural factors, forms a complete landscape gradient, namely urban-suburban-rural-natural (USRN). The complex dynamics of the USRN gradient landscape can reflect the evolutionary process of the entire social-natural ecosystem9,10. From local and regional to global scales, USRN landscape gradients are manifested at different spatial scales and orientations, revealing several key spatial phenomena, such as rural-urban linkages, land-use transitions, and urban sprawl, that contribute to increased spatial heterogeneity11. Quantifying the complete landscape gradient structure facilitates monitoring of ecosystem services, enhances understanding of urban-rural linkages, and facilitates achievement of sustainable development goals12.

Currently, there are already many mature urban datasets. Satellite remote sensing data offer significant potential for delineating urban extents over a long time series13. Current datasets primarily rely on satellite-derived indicators such as impervious surfaces, nighttime lights, and population distribution to monitor urban dynamics14. Integrating multi-source data, including impervious surfaces, nighttime lights, and points of interest (POI) has become a mainstream approach for defining urban boundaries15,16. However, existing studies predominantly focus on urban areas, often neglecting rural landscapes17. While some attempts have been made to distinguish urban and rural landscapes using these datasets, they tend to overemphasize residential attributes while overlooking functional differences in landscape characteristics18. Although numerous urban-focused products have been developed, research on landscape gradients remains limited, particularly in generating long-term gradient landscape datasets19. Most studies rely on socioeconomic data types such as nighttime lights, impervious surfaces, POI, and land use data. For individual gradient landscapes, various methods, including kernel density analysis, cellular automata, and K-means clustering—have been applied to classify urban, suburban, and rural areas based on impervious surfaces, nighttime lights, and population density20,21. Research on landscape gradients is highly diverse, encompassing: The wildland-urban interface, where human-environment conflicts and risks are concentrated22,23; The urban-rural-natural (URN) gradient, which integrates functional differences across landscapes10,11,24,25; Specific transitional zones such as the rural-urban interface20,26. Although the above studies have identified gradient landscapes from different aspects, there is currently a lack of a complete gradient landscape dataset.

The cities defined by gradient landscapes differ from the physical boundaries of cities. Due to the heterogeneity, comprehensiveness, and multi-scale characteristics of landscapes, there are also differences in the division of urban and rural areas between the landscape scale and the patch scale (land use classification). The urban-rural boundary at the patch scale (land use classification) is a physical one, while at the landscape scale, different patches are coupled to form a gradient, which reflects the multi-functionality of the landscape. Landscape multifunctionality is a defining feature of gradient landscapes, arising from the interactions of diverse landscape types within socio-natural ecosystems27. As urban expansion intensifies, the multifunctionality and spatial configuration of landscapes along the urban-rural gradient grow increasingly complex, challenging the traditional urban-rural dichotomy28,29. Suburban areas, serving as the frontier of urban-rural development20, act as critical transition zones where urban and rural landscapes converge, exhibiting distinct functional diversity30. Given their dynamic land-use changes, precise delineation of suburban boundaries is essential for targeted policy formulation to manage and protect these regions31, as their sustainable development is pivotal for achieving urban-rural equilibrium. However, the inherent spatial complexity and boundary ambiguity of suburban areas have hindered the development of robust quantitative identification methods and long-term datasets32. Moreover, the growing complexity of socioeconomic systems necessitates moving beyond the conventional urban-rural binary to better understand landscape connectivity. Research on gradient landscapes should thus prioritize the functional role of suburban areas33, refining landscape gradient classification and advancing theoretical frameworks for ecosystem services, land use, and sustainable development34. By conceptualizing the urban-suburban-rural-natural (USRN) gradient, we can extend traditional urban-rural linkages to a more holistic perspective, facilitating a deeper understanding of the spatial continuum between urban and rural systems35.

In this study, Southwest China was selected as a case study due to its status as a hotspot for geographic landscape diversity in Eurasia. The region features a significant topographic gradient, transitioning from a plain at an elevation of 500 m to a plateau with snow-covered mountains at 7,000 m. This area contrasts a megacity with a population of 20 million with barren natural landscapes, showcasing a remarkable variety of both natural and cultural environments. It represents a geographic space characterized by transitional and gradient coupling. Furthermore, the extensive mountainous terrain contributes to the complexity and variability of the land surface. This diversity and uncertainty provide an excellent opportunity for researching USRN gradient landscapes. To extend the research on gradient landscapes to the complete USRN gradient and depict the landscape gradient, we took Southwest China as a case study and developed the first regional 1-km Urban-Suburban-Rural-Natural (USRN) dataset from 1986 to 2021. It can provide new insights into landscape patterns and sustainable development. Meanwhile, it lays a foundation for research in different fields, such as urban-rural connections, land use transitions, urban sprawl, and the monitoring of ecosystem services and land management, across the complete landscape gradient.

Methods

Data collection

Table 1 details the basic data selected in this study and various data products used for comparison. We used the global 30 m impervious surface dataset (1985–2021)36 and the Chinese 30 m cropland dataset (1986–2021)37 to map the extent of landscape gradients in the time series of the Southwest region. Compared with the approach of interpreting and extracting the nighttime light and impervious surface data by using multi-source remote sensing data, using the existing high-resolution and high-precision datasets can reduce the errors indirectly generated in our interpretation process36. The global impervious surface dataset was produced using the GEE platform using 30m-resolution Landsat imagery combined with nighttime lighting data and Sentinel-1 synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data to produce 30m-resolution impervious surface data on a global scale, with an overall accuracy of more than 90%.

The Chinese cropland dataset was based on Landsat image maps, and the distribution of cropland in China at 30 m resolution from 1986 to 2021 was mapped by Random Forest Classification using the Land Trendr temporal segmentation algorithm, and the F1 score of the annual maps of the CACD was 0.79 ± 0.02, which was better than other products such as CLCD, CLUD, GLAD, and GFSAD at the superior accuracy37. Since the impervious surface data were in tile format, we performed raster mosaics through ArcGIS software and extracted the annual impervious surface dataset by attributes for the Southwest region; the cropland data were extracted by attributes for the annual cropland dataset for the Southwest region. According to the size of the study area, we constructed a 1-km grid and unified the GAIA and CACD data to a resolution of 1 km. The time range was unified to 1986–2021, and the projection coordinate system was unified to WGS 1984 UTM Zone 48 N.

In addition, in this study, to further validate the identification results, data specifically for Chinese urban are selected: the Standardized Dataset of Built-up Areas of Chinese Urban with a Population of 300,000 or More from 1990 to 2020 (SUB)19; China’s official statistical data (https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/): the Statistical Yearbook of China’s Urban Construction (CSY); and the data for the study of global city boundaries: Global Urban Boundary Dataset (GUB), which maps global city boundaries from global data of artificially impervious areas (GUB)14. Additionally, the study incorporated the Harmonized Global Urban Boundary Dataset (1992–2020) derived from calibrated nighttime light data (UMG)38. The comparisons are made in multiple dimensions of temporal stability and spatial morphological integrity, respectively.

Methodological framework

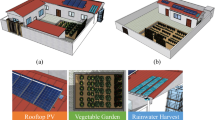

Based on a new fusion framework (Fig. 1), we mapped the gradient landscape ranges of USRN in Southwest China from 1986 to 2021. Specifically, it includes four parts: (1) Preliminary identification of USRN: First, a 1-km fishnet was created, and the impervious surface and cropland data with a resolution of 30 m were aggregated to a resolution of 1 km. The proportions of impervious surface and cropland in each grid were calculated through zonal statistics. Then, the grids were preliminarily classified according to the predefined identification matrix. Finally, the identified results were converted into raster data to obtain the preliminary identification results. (2) Gap filling based on the MSPA model: We extracted the distributions of the four gradient landscape types and reclassified them in turn, dividing them into foreground values and background values. Then, the MSPA model was used to identify the reclassified results, and further reclassification was carried out according to the definitions of different landscapes by MSPA to obtain the results of MSPA filling. (3) Boundary smoothing based on morphological closing operation: Based on the results optimized by MSPA, we needed to smooth the edge pixels of different gradient landscapes. Through the morphological closing operation (i.e., dilation first and then erosion), a 3 × 3 moving window was set to obtain the final identification results. The following sections will focus on the key parts of the framework.

Gradient landscape identification matrix

To prepare the recognition matrix, we initially established a 1-km grid. The selection of this grid size was deliberate for several reasons. Firstly, we chose Southwest China, encompassing Sichuan Province, Yunnan Province, Chongqing Municipality, and Guizhou Province, as our study area due to its vast expanse of 1.1388 million square kilometers, spanning significantly in both east-west and north-south directions. The utilization of a 1-km grid enables the representation of macroscopic spatial heterogeneity while capturing gradient landscape features at medium and small scales. Secondly, a 1-km grid facilitates the integration of diverse data sources, enhancing data comparability. Lastly, employing a 1-km grid reduces computational complexity, particularly advantageous for large-scale model operations. A resolution of 1 km takes into account the comprehensiveness and heterogeneity of the landscape. If the resolution is too large, the landscape types may lose their landscape significance, while if it is too small, it may turn into a land-use classification. A 1-km resolution can show the dominant landscape types in the region. Consequently, the 1-km grid facilitates the identification of landscape gradients, enables the calculation of various ecosystem service indicators, and streamlines subsequent research processes39.

Notably, the USRN dataset is a classification of different landscape types, emphasizing the multi-functionality of landscapes. However, the selection of thresholds is crucial for landscape multi-functionality. In previous studies, a single threshold was commonly used to identify urban, suburban, or rural areas, neglecting the functionality of landscapes. The emergence of the multi-threshold method overcomes the limitations of the single-threshold method. Table 2 summarizes cases in many previous studies that distinguish urban, suburban, or rural areas based on a single threshold. The common threshold ranges are as follows: urban areas (impervious surface proportion >50%), suburban areas (impervious surface proportion between 25% and 50%), and rural areas (cropland proportion >50%). Based on the thresholds in these studies, we combined impervious surfaces and cropland for threshold division18,34,40.

On this basis, we further constructed a landscape recognition matrix for the division of USRN (Fig. 2). We emphasize the combined effect of impervious surfaces and cropland, and determine the final gradient landscape type based on the dominant factors within the grid. Within a 1-km grid, cities, suburban, and rural areas are first classified according to the proportion of impervious surfaces. Specifically, areas with an impervious surface proportion greater than 50% are classified as cities, those with a proportion between 25% and 50% as suburban, and those with a proportion less than 25% as rural areas. Secondly, we further subdivide the landscape types classified in the previous step based on the proportion of impervious surfaces according to the proportion of cropland. If the impervious surface proportion is greater than 50% and the cropland proportion is greater than 25%, the grid is further classified as a suburb. If the impervious surface proportion is between 25% and 50% and the cultivated land proportion is greater than 50%, the grid is further classified as a rural area. Areas where the proportions of both impervious surfaces and cropland are 0 are classified as natural areas. These grids are characterized by areas that have not been intensively developed and utilized by humans, including forests, grasslands, wetlands, etc. Since cropland and impervious surfaces are mainly used for human activities in areas such as urban, suburbans, and rural areas, natural landscapes are indirectly identified through the process of elimination.

After determining the thresholds for different landscape types by the above method, we used the partition statistics tool in ArcGIS, for each partition in the input grid, the partition area will determine the total area of each partition, respectively, the percentage of impervious surface and cropland in the 1-km grid in Southwest China. Afterwards, our table tool summarizes the results of the partition statistics, with the UID field representing the corresponding and unique grid cell. After completing all the statistics, we used Arcpy to code the initial classification of gradient landscapes according to the recognition process in Fig. 1. After the classification was completed, we imported the results of the classification into ArcGIS, and through the vector-to-raster tool, we converted the vector data into raster data with unique values to generate a landscape gradient map of Southwest China from 1986 to 2021.

Morphology-based optimization process

In previous urban datasets, traditional morphological dilation and erosion are often used to improve urban boundaries and fill internal holes. This method is suitable for improving single-type landscape morphology. However, for the four landscape types we classified, it is insufficient to use only traditional morphological dilation and erosion to improve the landscape system, as it may cause one landscape to mask the characteristics of other landscapes. The MSPA model can identify binary raster images and divide them into seven mutually exclusive categories to describe spatial patterns, monitor the edge effects of images affected by width, and provide information on landscape type changes. Therefore, we integrated the MSPA model and morphological closing operation to optimize the preliminary identification results of USRN. In the MSPA model, the size of the structural element is usually set to 1–3 pixels for regional-scale analysis. Meanwhile, in morphology, a 3 × 3 window is widely used for 1 km resolution data to suppress classification noise and maintain landscape heterogeneity41.

Figure 3 shows the influence of different window sizes on the results. A larger window (e.g., 5 × 5) may over-smooth the urban-rural transition zone, which is crucial in gradient landscape research42. Figure 4 illustrates the operation processes of the MSPA model and morphological closing operation. On the one hand, we regard urban space as the sum of all landscapes with urban functions. Therefore, parks and water bodies in the city should also be considered as part of the city and converted into corresponding urban pixels43. Taking the optimization of urban pixels as an example, in Fig. 4, we can see that some pixels in the middle of urban pixels are misidentified as suburban or rural areas. We set urban pixels as the background value and other gradient landscape pixels as the foreground value, and then use the MSPA modelling software to identify the reclassified results. The MSPA model can identify islets, edge openings, etc. in the foreground value. We reclassify these pixels as urban pixels. The same processing method is applied to the gradient landscapes of suburban, rural, and natural areas. This reclassification hypothesis based on spatial continuity can effectively reclassify patches such as lakes and parks in the city as urban landscapes. Meanwhile, it can also correct the minor deviations caused by the fishnet boundary.

On the other hand, traditional single landscape identification does not consider the relationships between different landscape edges. However, in the process of identifying the complete landscape gradient, the edges of different landscape types are the most complex areas. Some green spaces and water bodies located at the edges of cities or suburban are identified as natural areas. In response, we adopted another morphological method, namely dilation and erosion. We used morphological closing operations to optimize the edge pixels of different landscapes. The resolution of the original data is 1 km, and the 3 × 3 window represents the first-order adjacency of the landscape, which can better demonstrate landscape heterogeneity; using a larger moving window may weaken the landscape heterogeneity44.

The results indicate that the urban gaps can be effectively identified through the MSPA model. The same treatment is also applicable to suburban areas, rural areas, and natural landscapes. Meanwhile, the boundaries of the gradient landscape are optimized by morphological closing operation. Finally, by merging the optimized results with the original raster image, we obtain more accurate results.

Accuracy assessment

The USRN dataset identifies the complete gradient landscape. However, due to the current lack of data on rural and natural areas, we selected the existing research data on urban landscapes, which are relatively abundant, to validate the accuracy of our identification. In the research on urban landscape identification, the most used data are impervious surface and night-light data. We selected the urban extents extracted based on impervious surface and night-light data. Meanwhile, we introduced the statistical yearbook data from government departments to further compare and validate the results identified by USRN. Specifically, we compared the USRN data with other data products from three aspects.

Firstly, the stability of the data time series. Although the USRN data further divides cities into urban and suburban areas, inconsistencies in the definitions of cities across different datasets can lead to significant disparities. To enhance comparability and mitigate the impact of these differences, we separately extracted the urban and suburban areas from USRN and compared these two parts with the cities identified by GUB, SUB, CSY, and UMG respectively. We compared the identified urban areas from three aspects: area, spatial morphology, and growth rate, to validate the accuracy of the urban landscapes identified by USRN. We selected annual data every five years from 1995 to 2020 for comparison (the CSY dataset has records starting from 2002).

Secondly, the integrity of the spatial form. By overlaying Google image maps, we found that for cities with different expansion patterns, the urban dynamics identified from the USRN dataset also match well with the actual urban extent in the image maps. Meanwhile, we compared the vector boundary data of nature reserves in China with the natural areas identified by USRN, and selected image maps of some results for comparison. The results showed that the natural areas identified by USRN also had high accuracy. Based on the verification of temporal stability and spatial integrity, we employed landscape pattern indices to analyze the urban aggregation and fragmentation degrees among different datasets. Previous datasets overlooked urban morphology during verification, while urban spatial morphology is of great significance for determining the direction of urban spatial development. Therefore, in this study, we compared the urban spatial morphologies among different datasets through landscape pattern indices when verifying spatial integrity, thereby better validating the spatial integrity of our dataset45,46,47. This paper referred to the commonly used indicators in existing studies and selected eight indices from three aspects: area, shape, and distribution, including: Landscape Shape Index (LSI), Division Index (DIVISION), Patch Density (PD), Aggregation Index (AI), Cohesion Index (COHESION), Patch - weighted Mean Fractal Dimension (FRAC_AM), Largest Patch Index (LPI), and Edge Density (ED), which were used to evaluate the urban morphologies of different datasets in different periods41. Considering morphological influences, particularly topographic factors, we selected representative cities: Chengdu (plains-dominated), Chongqing (mountainous), Kunming (plateau), and Mianyang (small-medium city), ensuring comprehensive assessment of dataset stability across urban types.

Finally, the comparison with socioeconomic data. We selected the USRN data and population data at five-year intervals from 2000 to 2020 for comparison. By extracting the population within the urban areas in the USRN, we found a high correlation between the cities identified by USRN and the population through linear fitting.

Data Records

The current version of the USRN dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1734009448. The dataset is formatted as Geo TIFF files under the WGS 1984 UTM Zone 48 N projected coordinate system, with a spatial resolution of 30 arcsec (~1-km). In these Geo TIFF files, pixels with a value of 1 represent natural areas, pixels with a value of 2 represent rural areas, pixels with a value of 3 represent suburban areas, and pixels with a value of 4 represent urban areas. These data can be processed using ArcGIS, QGIS, and other tools.

Technical Validation

Temporal stability assessment of the USRN dataset

First, we conducted linear fitting of the USRN identification results with four datasets respectively and calculated R2 to verify the accuracy of the USRN dataset. Figure 5 shows the consistency between the USRN dataset and the other four datasets. Overall, the USRN dataset maintains high consistency with the other four datasets, especially after 2000, with all R2 greater than 0.84. This indicates that the threshold selection of our dataset aligns with the results of most urban datasets. However, due to differences in methods and basic data sources among datasets, slight discrepancies between USRN and other datasets are acceptable. Figure 5 also shows that although the correlation between the USRN dataset and the SUB dataset is high, it generally shows a downward trend. It is worth noting that the difference in urban areas between the USRN dataset and CSY statistics is small in the early stage of urbanization but gradually widens in the middle and later stages. This is because of the different definitions of cities. CSY defines the built-up area of a city as the area within the urban administrative region that has been developed in patches and is basically equipped with municipal and public facilities, and it is often restricted by administrative divisions. As the urbanization process accelerates and the urban structure becomes more complex, CSY’s definition of cities has difficulty breaking through these restrictions, which calls for a more efficient method to determine the size of urban landscapes.

Secondly, we combined the urban and suburban areas in the USRN dataset and compared it with four other datasets, as shown in Fig. 6. After considering the suburban landscape, the correlations between the USRN dataset and UMG, GUB, and CSY all improved, which also reflects the advantage of the USRN dataset in identifying suburban areas from a side perspective. However, the correlation between USRN and SUB significantly decreased, with an R2 of 0.67 in 2020, because SUB only identified the urban built-up areas and ignored the important gradient landscape of the suburbs. Although the other groups of datasets all identified urban areas, they did not separate the suburbs, which ignores the spatial heterogeneity of the landscape. With the development of suburban urbanization, the spatial changes of cities are becoming more complex, requiring us to have a more comprehensive understanding of the suburban.

We calculated the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between USRN and other urban datasets. The results show that as the urbanization process accelerates, the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the USRN dataset and other urban products continuously increases, with the greatest change occurring in the GUB dataset. In addition, we found that when the urban and suburban areas in USRN are combined and compared with other datasets, the RMSD decreases. This change is reasonable and also demonstrates the importance of the USRN dataset in identifying suburban landscapes.

We further generated binary maps of the urban spatial extents of several datasets (Fig. 7) and compared the spatial morphologies of different cities at different times. Figure 6 shows that USRN has high consistency with GUB and UMG in terms of spatial morphology. However, the urban extent produced by UMG has overly smooth boundaries, weakening the boundary effect of cities. Compared with the other three datasets, the urban morphology identified by SUB is very fragmented, with numerous holes inside the cities. SUB fails to recognize landscapes such as water bodies and green spaces in cities as urban spaces and cannot reflect the real changes in urban space. The comparison of spatial morphologies demonstrates that the urban spatial morphology identified by USRN over a long-term sequence is reasonable, proving its temporal stability. Notably, we delineated urban and suburban areas in the binary map of USRN. From the presentation in Fig. 7, we can identify the spatial development patterns of urban and suburban areas, while the other three datasets can only show the changes in urban areas.

We calculated the growth rates of urban areas in different datasets for three periods: 2005–2010, 2010–2015, and 2015–2020 (Fig. 8). From Fig. 8, we found obvious differences among different datasets. Among them, SUB only counts cities with a population of over 300,000 in China. However, there is a problem with this definition itself. The continuous change of urban population leads to omissions in SUB’s identification of many cities, and the growth rate of urban areas counted by SUB is significantly lower than that of several other datasets. The urban growth rate of GUB varies greatly across different periods. Especially during 2015–2020, the growth of most cities exceeded 200%, indicating that GUB lacks temporal stability, and there were obvious errors in 2015, which we also specifically demonstrated during the subsequent verification of spatial integrity. USRN, UMG, and CSY show good consistency in urban growth rates. Especially between 2010 and 2015, the urbanization speed accelerated significantly, and some small and medium-sized cities expanded rapidly. In contrast, several large cities in the southwestern region started urbanization earlier, and their urban growth rates were relatively stable, which also reflects the differences among different types of cities during the expansion process. Figure 8 shows that the growth rate of cities identified by USRN in different periods is reasonable and consistent with the urbanization process in different regions.

Variations stemming from discrepancies in defining urban boundaries across datasets, including differences in definitions, data sources, and delineation methods, are deemed acceptable. For instance, metrics like nighttime lights or impervious surfaces may fail to capture green spaces or water bodies such as urban grasslands, parks, and lakes with lower brightness and density49. Official statistical data, on the other hand, may be influenced by administrative demarcations. Moreover, the spatial distribution of various functional zones within cities, such as industrial areas and suburbs, can also impact the outcomes of our identification efforts38. We rigorously assessed the temporal consistency of the USRN across three dimensions: area, shape, and rate of change. These comparative evaluations validate the USRN’s efficacy in delineating urban-rural transitions by incorporating cropland and impervious surfaces. The observed discrepancies fall within the anticipated range of variability inherent in diverse urban mapping products.

Spatial integrity assessment of the USRN dataset

Figure 9 shows the boundary between the urban and suburban areas identified by USRN and the image maps of four cities (Chengdu, Kunming, Nanchong, and Guiyang) from 1990 to 2020 (at five-year intervals). By overlaying the changes in the image maps of the suburban boundaries, we found that cities have experienced significant growth over the past 30 years. Especially during the period from 2015 to 2020, there was obvious urban expansion. Figure 9a,b show the enlarged image maps of the urban fringe areas. We overlaid the urban extent identified by SUB to demonstrate the spatial integrity of USRN. As can be seen from Fig. 9a,b, the urban boundary identified by USRN is smoother, while the urban extent identified by SUB is extremely fragmented, and several obvious holes are circled in the Fig. 9a,b. In particular, in Nanming District of Guiyang, this area contains several large-scale ecological parks and tourist resorts, and SUB missed this part of the urban area. This error hinders the accuracy of our study on urban expansion. In contrast, the urban extent derived from USRN can better depict the details of urban expansion and the complex expansion patterns of polycentric urban.

It should be emphasized that the USRN has unique advantages in suburban area identification. We illustrate the differences between the UMG and SUB datasets and the USRN in suburban area identification through Figs. 10, 11. Figure 10 shows the urban scope of Chengdu City in 2015 identified by the UMG and the suburban scope of Chengdu City in 2015 identified by the USRN, where Fig. 9a–d show the specific differences. Specifically, Fig. 10a shows the area that was not identified by the UMG dataset. The enlarged image shows this area. By querying the corresponding electronic map, it was found that this area is the location of the municipal government of Qingbaijiang District in Chengdu, so it should be classified as urban, but the UMG did not identify this area. Figure 10c,d show the areas that were mis-identified as urban by the UMG. Figure 9b is Meixiang Lake in the Sansheng Huaxiang Tourist Area of Jinjiang District in Chengdu; Fig. 9c is the Intangible Cultural Heritage Expo Park in Chengdu; and Fig. 10d is the Lafite Manor in Jinniu District of Chengdu. These three areas have common characteristics: they are located outside the Third Ring Road of Chengdu; there are large areas of green space or water bodies around; the building density is low, and most of them are leisure and cultural facilities or high-end residential areas. These areas are classified as suburban in the USRN, while the UMG classifies them as urban. A similar case is shown in Fig. 11. Figure 11 shows the urban scope of Guiyang in 2020 identified by the SUB and the USRN. It can be found that there are a large number of holes inside the city identified by the SUB, and the edges are extremely fragmented. Figure 11a–d show the areas that were not identified. Figure 11a is the Baijinggu Wetland Park in Guiyang; Fig. 11b is the Luchongguan Forest Park; Fig. 11c is the Taiyang Lake and the Automobile Industrial Park in Baiyun District of Guiyang; and Fig. 11d is the Golf Club. Most of these areas are urban ecological parks or industrial parks, etc., located on the edge or inside of the city, and should be classified as suburban according to their functional characteristics. However, the SUB dataset did not identify these areas, while the USRN dataset identified these areas as suburban. The USRN can better identify the suburban areas within the city, providing a clearer reference for landscape planning.

In addition, USRN has strong advantages in identifying some small and medium-sized cities. Through the comparison in Fig. 12, there are obvious differences in the spatial scope of Yibin in 2015 determined by GUB and USRN. The GUB data failed to identify the urban area of Yibin in 2015 but determined the urban scope of Yibin in 2020. This deviation hinders our research on these small and medium-sized cities. On the other hand, the USRN data is a continuous dataset with a long series, and the results of each year are generated based on the results of the previous year. In contrast, the GUB data has an interval of 5 years and is easily affected by the errors of the basic data, resulting in a decrease in its spatial integrity14.

The current urban-rural dataset focuses on the description of urban-rural clusters. In fact, there are large areas of cultivated land in rural areas. Our definition of villages includes large areas of cultivated land and small areas of settlements, which leads to the lack of comparability between USRN and villages in other datasets. However, the dataset on natural areas is still blank. We use nature reserves to verify the natural areas identified by USRN50. According to the vector boundary of China nature reserves, we extracted cultivated land and natural areas identified by USRN. We excluded cases where cultivated land accounted for more than 20% of nature reserves, in order to reduce the impact of cultivated land on accuracy verification. On this basis, we compared the area of eligible nature reserves with the area of natural landscapes identified by USRN. Figure 13a shows that the R2 of USRN and nature reserves was 0.7. Figure 13b,c show the superposition of Guizhou Fanjingshan Nature Reserve and Yunnan Wenshan Nature Reserve with USRN, while Fig. 13d–k show some details. The comparison of the images shows that the natural landscape identified by USRN is consistent with the nature reserve, but Fig. 13d–k shows that there are still large areas of settlements and cultivated land in these two nature reserves, which are classified as rural landscapes in USRN. Therefore, we find that nature reserves are not pure natural landscapes, and the delimitation of nature reserves boundaries is affected by subjective and objective factors, and often contains multiple landscape types. The USRN distinguishes between natural and rural landscapes, which confirms that USRN fills in the gaps in the division of rural and natural landscapes. In addition, we show more USRN images of natural landscapes versus nature reserves in Fig. S1.

Comparison of landscape pattern indices among different datasets

We presented four indices with obvious differences, namely LSI, AI, ED, and LPI, in Fig. 14. We found that with the passage of time, the LSI values of the four datasets in four different cities all increased, indicating that the complexity of urban morphology was constantly increasing with the acceleration of urbanization. However, among the four datasets, the LSI of the urban extent derived from UMG was the lowest. As shown in Fig. 7, the edge of the urban extent derived from UMG was too smooth, indicating that UMG data was deficient in identifying urban morphology. This was because during the rapid urbanization process, the functions of cities were decentralized, and living and working spaces showed a separation trend. Some industrial and high-tech industries in cities migrated to the suburban, and these areas might affect the identification of urban morphology by UMG data. In contrast, the LSI values of USRN data, GUB data, and SUB data were highly consistent in the three cities of Chengdu, Kunming, and Mianyang. These three datasets all identified the urban spatial extent based on impervious surfaces, so they could better identify the urban fringe areas and depict urban morphology. However, for Chongqing, a mountainous city with a multi-centered urban structure, its urban morphology was affected by topography, making it more complex. SUB data did not depict the urban morphology of Chongqing well. Overall, the USRN dataset has certain advantages in depicting urban morphology.

The AI represents the connectivity and aggregation degree of urban patches. As shown in Fig. 14, there are certain differences in the AI values among the four datasets. Notably, the AI of the SUB dataset is significantly lower than those of the other three datasets51. As can be seen from Fig. 6, there are numerous voids within the cities identified by the SUB dataset. The relatively low Aggregation Index (AI) of the SUB dataset is attributed to its physical definition of ‘city’ (i.e., based solely on impervious surfaces). Consequently, it fails to recognize the pervious surfaces within the city (such as green spaces and water bodies) as part of the city, resulting in a fragmented urban morphology. In contrast, the USRN adopts a functional urban definition, incorporating these spaces that serve urban ecology and residents’ lives into the urban category, thereby achieving a higher degree of spatial aggregation.

Demographic statistical validation of the USRN dataset

Since urbanization can be characterized in various ways, including many indicators such as population, urbanization rate, and urban land use. Given that there is usually a power-law relationship (allometry) between urban population and urban areas, logarithmic transformation can linearize this relationship, thus facilitating visualization and analysis. Therefore, we used the urban areas delineated by the USRN to extract the total population of the corresponding areas from the LandScan Global Population Grid (LSG)52 data, so as to verify the consistency between the urban areas delineated by the USRN and the actual population agglomerations53. We calculated a plot of urban area versus population in the USRN for a five-year interval from 2000 to 2020, and we found that the consistency between USRN and total population increased over time (Fig. 15). R2 increased from 0.62 in 2000 to 0.88 in 2020, while RMSD between urban area and total population also declined, from 0.45 in 2000 to 0.17 in 2020. This suggests that as urbanization accelerates, populations tend to cluster in cities. In supplementary material Fig. S2, we show the comparison chart of unconverted city area and total population54. It can be seen from Fig. S2 that there is still a high consistency between city area and total population, but RMSD is increasing, because logarithmic change will weaken the large data error, while the original result shows this result better. Some large cities attract a large number of people, but the expansion rate of city area is lower than the growth rate of population. This results in an increase in RMSD results.

In addition, we analyzed the consistency between the suburbs of the four representative cities in Southwest China and the socio-economic data. We counted the areas of Chengdu, Chongqing, Kunming and Guiyang suburbs in 2000, 2010 and 2020 respectively, and extracted the total population and GDP within the suburbs of these places. As shown in Fig. S3, the agreement between suburban area and population is significantly lower than that between urban area and population, indicating some heterogeneity between suburban distribution and population distribution. Because suburbs are transitional areas between urban and rural areas, the versatility of suburban landscapes is more complex and there are large differences between different regions. The consistency between suburban area and GDP is further reduced because the factors affecting socio-economic development are more complex. Suburbs not only have industrial areas, but also a large number of cropland, green space, etc. Its economic development does not have obvious aggregation characteristics, but presents scattered aggregation characteristics.

Usage Notes

USRN applications

USRN transcends the traditional urban-rural dual structure. Due to the lack of large-scale gradient landscape mapping with long-time series, the USRN dataset has the potential to support extensive interdisciplinary research and practical applications that require a nuanced understanding of landscape gradients. Its main utility lies in regional-scale analysis (such as at the provincial or river-basin level) over a 35-year period (1986 2021). Specifically, the USRN dataset can be applied to:

-

(1)

Research on urban-suburban-rural-natural connections. By clearly defining four gradient categories, this dataset enables researchers to quantify the intensity, direction, and speed of interactions between urban cores and their rural hinterlands, such as population flow, capital, and ecosystem services.

-

(2)

Landscape pattern and ecosystem service assessment. The continuous gradient framework provides a more realistic basis for simulating and monitoring changes in ecosystem services (e.g., carbon sequestration, water purification, habitat provision) across the urbanization continuum, going beyond the simple urban-rural dualism.

-

(3)

Sustainable urban and regional planning. Planners can use this dataset to identify key transition areas (especially suburban areas) experiencing rapid land - use changes, thereby informing targeted policies for infrastructure development, ecological protection, and agricultural land conservation.

Limitation and future work

Although the USRN dataset offers a novel perspective on landscape gradients, it has certain limitations and requires improvement in future research. First, in terms of spatial scale, while a 1-kilometer resolution is suitable for the study area, it is not appropriate for local-scale applications, such as municipal zoning, detailed habitat connectivity modelling, or site-specific environmental impact assessments, as fine-grained landscape features are aggregated. Second is the classification logic. The threshold for the “Urban” classification has been verified by many well-established studies. However, the “Urban” category includes functional urban spaces such as parks and lakes, which may lead to a slight underestimation of the population density within urban boundaries. The “Natural” category is a complex of all non-cultivated and non-permeable land covers (such as forests, grasslands, and water bodies), and it does not distinguish specific natural land cover types. Finally, regarding geographical transferability, the identification matrix (Fig. 2) and its thresholds were calibrated for the specific socio-ecological context of the southwestern region with complex terrain and a unique urbanization pattern. Directly applying this framework to other regions (e.g., arid areas, coastal megacities, or regions with different agricultural systems) may require recalibrating the thresholds based on local empirical data or high-resolution verification. Furthermore, verifying rural and natural landscapes remains a challenge at present. This requires us to create sample sets with a sufficient number of fine samples for manual verification. Therefore, this datasets does not verify the rural landscapes. Regarding the verification of natural landscapes, we emphasize that this is a regional comparison rather than a powerful verification method, because the demarcation of nature reserves is a land marker, not a complete collection of natural landscapes in the sense of landscape. Based on the above limitations, future work can enhance the framework in the following ways: (1) Incorporate additional data layers, such as points of interest for suburban socioeconomic verification and high-resolution land cover for natural category refinement; (2) Conduct a systematic sensitivity analysis of the classification thresholds; (3) Develop a machine-learning-based method to automate and generalize the gradient mapping process over a larger geographical area.

Data availability

The least version of USRN dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1734009448.

Code availability

The platform used for generating the dataset and analyzing the results is ArcGIS Pro (3.2). We called the Arcpy module in Python (3.9) to quickly implement data processing. The code for data processing can be obtained at https://github.com/fjh1826287122/USRN.git.

References

Boesing, A. L. et al. Identifying the optimal landscape configuration for landscape multifunctionality. Ecosyst. Serv. 67, 101630, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134474 (2024).

Ma, L. et al. Evolution and simulation optimization of rural settlements in urban-rural integration areas from a multi-gradient perspective: A case study of the Lan-Bai urban agglomeration in China. Habitat. Int. 153, 103203, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2024.103203 (2024).

Kotikula, A. & Raza, W. A. Housing ownership gender differences in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Land Use Policy. 110, 104983, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104983 (2021).

Liu, Z., Huang, S., Fang, C., Guan, L. & Liu, M. Global urban and rural settlement dataset from 2000 to 2020. Sci. Data. 11, 1359, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04195-y (2024).

Esch, T. et al. Breaking new ground in mapping human settlements from space–The Global Urban Footprint. ISPRS. J. Photogramm. 134, 30–42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2017.10.012 (2017).

Fang, C. & Liu, Z. J. G. & Sustainability. Earth vitality: An integrated framework for tracking Earth sustainability. Geogr. Sustain. 5, 96–107, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2023.11.002 (2024).

Li, X., Gong, P. & Liang, L. A 30-year (1984–2013) record of annual urban dynamics of Beijing City derived from Landsat data. Remote. Sens. Environ. 166, 78–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2015.06.007 (2015).

Marconcini, M. et al. Outlining where humans live, the World Settlement Footprint 2015. Sci. Data. 7, 242, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00580-5 (2020).

Deng, W. et al. Dynamic Identification and Evolution of Urban-suburban-rural Transition Zones Based on the Blender of Natural and Humanistic Factors: A Case Study of Chengdu, China. Chinese Geogr. Sci. 34, 791–809, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11769-024-1455-4 (2024).

Vizzari, M., Hilal, M., Sigura, M., Antognelli, S. & Joly, D. Urban-rural-natural gradient analysis with CORINE data: An application to the metropolitan France. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 171, 18–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.11.005 (2018).

Vizzari, M. & Sigura, M. Landscape sequences along the urban–rural–natural gradient: A novel geospatial approach for identification and analysis. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 140, 42–55, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.04.001 (2015).

Ortiz-Báez, P., Cabrera-Barona, P., Bogaert, J. J. J. O. U. & Analysis, R. Analysis of landscape transformations in the urban-rural gradient of the metropolitan district of Quito. J. Urban. Reg. Anal. 14 (2), https://doi.org/10.37043/JURA.2022.14.2.4 (2022).

Zhu, Z. et al. Understanding an urbanizing planet: Strategic directions for remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 228, 164–182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.04.020 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Mapping global urban boundaries from the global artificial impervious area (GAIA) data. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094044, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab9be3 (2020).

Shi, K. et al. Mapping and evaluating global urban entities (2000–2020): A novel perspective to delineate urban entities based on consistent nighttime light data. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 60, 2161199, https://doi.org/10.1080/15481603.2022.2161199 (2023).

Zhao, M. et al. Mapping urban dynamics (1992–2018) in Southeast Asia using consistent nighttime light data from DMSP and VIIRS. Remote. Sens. Environ. 248, 111980, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.111980 (2020).

Feng, Z., Peng, J. & Wu, J. Using DMSP/OLS nighttime light data and K–means method to identify urban–rural fringe of megacities. Habitat. Int. 103, 102227, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102227 (2020).

He, T. et al. A new approach to peri-urban area land use efficiency identification using multi-source datasets: A case study in 36 Chinese metropolitan areas. Appl. Geogr. 150, 102826, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2022.102826 (2023).

Jiang, H. et al. A standardized dataset of built-up areas of China’s cities with populations over 300,000 for the period 1990–2015. Big Earth Data. 6, 103–126, https://doi.org/10.1080/20964471.2021.1950351 (2022).

Li, G. et al. Understanding the diversity of urban–rural fringe development in a fast urbanizing region of China. Remote. Sens. 13, 2373, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13122373 (2021).

Chen, B. et al. Wildfire risk for global wildland–urban interface areas. Nat. Sustain. 7, 474–484, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01291-0 (2024).

Kaim, D. et al. Growth of the wildland-urban interface and its spatial determinants in the Polish Carpathians. Appl. Geogr. 163, 103180, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2023.103180 (2024).

Schug, F. et al. The global wildland–urban interface. Nature. 621, 94–99, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06320-0 (2023).

Moreira-Muñoz, A., del Río, C., Leguia-Cruz, M. & Mansilla-Quiñones, P. Spatial dynamics in the urban-rural-natural interface within a social-ecological hotspot. Appl. Geogr. 159, 103060, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2023.103060 (2023).

Zhang, S., Deng, W., Zhang, H. & Wang, Z. Identification and analysis of transitional zone patterns along urban-rural-natural landscape gradients: An application to China’s southwest mountains. Land Use Policy. 129, 106625, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106625 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Agricultural space function transitions in rapidly urbanizing areas and their impacts on habitat quality: An urban–Rural gradient study. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 99, 107019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2022.107019 (2023).

He, Y., Wen, C., Fang, X. & Sun, X. Impacts of urban-rural integration on landscape patterns and their implications for landscape sustainability: The case of Changsha, China. Landsc. Ecol. 39, 129, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-024-01926-9 (2024).

Lin, T. et al. Spatial pattern of urban functional landscapes along an urban–rural gradient: A case study in Xiamen City, China. Int. J. Appl. Earth. Obs. Geoinf. 46, 22–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2015.11.014 (2016).

Sahana, M., Ravetz, J., Patel, P. P., Dadashpoor, H. & Follmann, A. Where is the peri-urban? A systematic review of peri-urban research and approaches for its identification and demarcation worldwide. Remote. Sens. 15, 1316, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15051316 (2023).

Wang, Q., Wang, H., Zeng, H., Chang, R. & Bai, X. Understanding relationships between landscape multifunctionality and land-use change across spatiotemporal characteristics: Implications for supporting landscape management decisions. J. Cleaner. Prod. 377, 134474, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134474 (2022).

Mortoja, M. G., Yigitcanlar, T. & Mayere, S. What is the most suitable methodological approach to demarcate peri-urban areas? A systematic review of the literature. Land Use Policy. 95, 104601, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104601 (2020).

Mou, L., Li, H. & Rao, Y. Identification and Spatial Characterization of suburban areas in Chengdu. Appl. Geogr. 172, 103428, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2024.103428 (2024).

Wang, R. et al. Impacts of urbanization at city cluster scale on ecosystem services along an urban–rural gradient: a case study of Central Yunnan City Cluster, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 88852–88865, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-21626-8 (2022).

Li, R., Xu, Q., Yu, J., Chen, L. & Peng, Y. Multiscale assessment of the spatiotemporal coupling relationship between urbanization and ecosystem service value along an urban–rural gradient: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, China. Ecol. Indic. 160, 111864, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.111864 (2024).

Chigbu, U. E. Urban-Rural Land Linkages: A Concept and Framework for Action. https://gltn.net/publications/urban-rural-land-linkages-concept-and-framework-action (2021).

Gong, P. et al. Annual maps of global artificial impervious area (GAIA) between 1985 and 2018. Remote. Sens. Environ. 236, 111510, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111510 (2020).

Tu, Y. et al. A 30 m annual cropland dataset of China from 1986 to 2021. Earth. Syst. Sci. Data. 16, 2297–2316, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-2297-2024 (2024).

Zhao, M. et al. A global dataset of annual urban extents (1992–2020) from harmonized nighttime lights. Earth. Syst. Sci. Data. 14, 517–534, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-517-2022 (2022).

Ahani, S. & Dadashpoor, H. Land conflict management measures in peri-urban areas: A meta-synthesis review. J. Environ. Plann. Manage. 64, 1909–1939, https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2020.1852916 (2021).

Qu, S. et al. Unveiling the driver behind China’s greening trend: urban vs. rural areas. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 084027, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ace83d (2023).

Unger Holtz, T. S. Introductory digital image processing: A remote sensing perspective. https://doi.org/10.2113/gseegeosci.13.1.89 (2007).

Michielsen, K. & De Raedt, H. Morphological image analysis. Computer Physics Communications 132, 94–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-4655(00)00139-9 (2000).

Yeh, C. T. & Huang, S. L. Investigating spatiotemporal patterns of landscape diversity in response to urbanization. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 93(3-4), 151–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2009.07.002 (2009).

Weng, Y. C. Spatiotemporal changes of landscape pattern in response to urbanization. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 81, 341–353, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.01.009 (2007).

Jia, Y., Tang, L., Xu, M. & Yang, X. Landscape pattern indices for evaluating urban spatial morphology–A case study of Chinese cities. Ecol. Indic. 99, 27–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.12.007 (2019).

Cheng, J., Pan, H., Yao, C., Zhang, T. & He, Y. Evolutionary rules and typical paths of urban spatial forms in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River Economic Belt: A case study of Sichuan Province. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 45, 822–834, https://doi.org/10.13249/j.cnki.sgs.20230941 (2023).

Frolking, S., Milliman, T., Seto, K. C. & Friedl, M. A. A global fingerprint of macro-scale changes in urban structure from 1999 to 2009. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 024004, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024004 (2013).

Fang, J. & Zhang, S. A 1 km annual dataset (1986–2021) of urban-suburban-rural-natural gradient landscape continuum in Southwest China. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17340094 (2025).

Wu, X. et al. Cropland non-agriculturalization caused by the expansion of built-up areas in China during 1990–2020. Land Use Policy. 146, 107312, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2024.107312 (2024).

China Nature Reserve Specimen Resource Sharing Platform. List and Vector Boundaries of Nature Reserves in China [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14875797 (2024).

Cheng, C., Yang, X. & Cai, H. Analysis of spatial and temporal changes and expansion patterns in mainland Chinese urban land between 1995 and 2015. Remote Sens. 13, 2090, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13112090 (2021).

Lebakula, V. et al. LandScan Global 30 Arcsecond Annual Global Gridded Population Datasets from 2000 to 2022. Sci. Data. 12, 495, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04817-z (2025).

Giménez, R., García, R., Serrano, J. & Pulido, M. Peri-Urban Dynamics in Murcia Region (SE Spain): The Successful Case of the Altorreal Complex. Urban Sci. 2, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci203006 (2018).

Gong, J., Jiang, C., Chen, W., Chen, X. & Liu, Y. Spatiotemporal dynamics in the cultivated and built-up land of Guangzhou: Insights from zoning. Habitat Int. 82, 104–112, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.10.004 (2018).

Zhou, D. et al. Spatiotemporal trends of urban heat island effect along the urban development intensity gradient in China. Sci. Total. Environ. 544, 617–626, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.168 (2016).

Xu, Z. et al. Mapping hierarchical urban boundaries for global urban settlements. Int. J. Appl. Earth. Obs. 103, 102480, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2021.102480 (2021).

Li, M., van Vliet, J., Ke, X. & Verburg, P. H. Mapping settlement systems in China and their change trajectories between 1990 and 2010. Habitat. Int. 94, 102069, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102069 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research work was carried out within the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 42571362, 41930651).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiahao Fang: Data curation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing-original draft. Shaoyao Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing, review & editing. Wei Deng: Conceptualization, Supervision, Resources, Writing-review & editing. Hao Zhang: Investigation, Software, Visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, J., Zhang, S., Deng, W. et al. A 1 km datasets for urban–suburban–rural–natural continuous gradient landscapes in Southwest China. Sci Data 12, 2010 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06266-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06266-0