Abstract

In 2023, an unprecedented marine heatwave (MHW) developed in the North Atlantic. MHWs have severe ecological and socioeconomic impacts, and their increasing frequency and intensity demand urgent action from climate scientists and policymakers. The characterisation of MHWs requires high-resolution observations not only of ocean temperature, but also of its physical drivers, such as wind and ocean waves. However, acquiring co-located, in-situ measurements of these variables remains logistically challenging, and data scarcity continues to hinder efforts to fully understand and model MHWs dynamics. Here, a dataset collected by a freely drifting buoy off the west coast of Ireland during the peak of the 2023 MHW event is presented. The dataset includes 1-minute sea surface temperature (SST) and position records, directional wave spectra, wind speed estimates, and derived wave parameters. These data provide a unique opportunity to analyse air-sea interactions during a MHW at fine temporal scales. They are intended to support coupled model validation, diurnal warming studies, and data assimilation efforts, ultimately contributing to improved understanding and forecasting of MHWs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Marine heatwaves (MHWs) pose a significant and urgent challenge in climate research due to their profound impact on marine ecosystems, human activities, and broader climatic systems. MHWs are defined as exceptionally high sea-surface temperature (SST) events, where “high” refers to temperatures exceeding a certain percentile (e.g. 90th) of the historical climatology. These events last for at least five days and occur within a specific geographic region, with well-defined start and end times1. Projections suggest that MHWs are expected to increase in frequency, intensity, and duration as the twenty-first century progresses2, a trend that underscores the urgent need to investigate the mechanisms driving these events and their broad ecological and socio-economic implications.

The rise in ocean temperatures during a MHW can disrupt marine ecosystems, leading to increased coral bleaching3, reduction of seagrass density and kelp forest biomass4, and modification of fish distribution and migration patterns5. Furthermore, MHWs influence atmospheric patterns and oceanic carbon uptake, thereby affecting global climate feedback mechanisms and the Earth’s carbon cycle6. Understanding these complex interactions is crucial for devising effective mitigation strategies and for the sustainable management of marine and coastal resources.

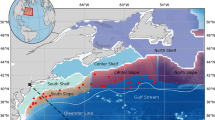

In the North Atlantic, recent years have seen record-breaking SST anomalies: for instance, boreal summer 2023 brought unprecedented basin-wide warmth. McCarthy et al.7 reported that the SST reached an extraordinary 4 °C above average off the Irish west coast. Berthou et al.8 described this event as unprecedented in terms of intensity and duration and attributed its occurrence to persistent anticyclonic weather with weak winds and extended sunshine that enhanced ocean stratification and water temperatures. They suggest that this event resulted in one of the fastest warming trends observed over the last 40 years. Supporting these conclusions, England et al.9 found that anomalous air-sea heat fluxes, influenced by exceptionally weak winds and a resultant shallow surface mixed layer, were the primary causes of the heatwave, discarding unusual ocean heat transport. Furthermore, Guinaldo et al.10 suggest that the June 2023 MHW event would not have been possible without anthropogenic climate change. Figure 1 illustrates the SST on 19 June 2023 in the North Atlantic waters around Ireland and Great Britain near the peak of the 2023 MHW event. Although the MHW affected the wider North Atlantic, this plot focuses on the region covered by the available observations.

These studies primarily rely on daily-averaged reanalysis products and satellite-derived data to monitor SST anomalies. While the extensive spatial coverage of these data is indispensable to identify large-scale patterns and evolution over time, in-situ SST measurements with high temporal resolution can capture rapid changes in oceanic conditions, which is essential, not only to calibrate and validate satellite-derived and reanalysis data, but also to better understand processes like diurnal warming11 or heat flux modulation by ocean waves12. It is precisely the role of ocean waves in the mixed layer dynamics that is of crucial importance for understanding complex air-sea interactions13,14.

In recent years, there has been a shift towards consensus regarding the significant role of wave-induced processes in influencing the mixing of the upper ocean15,16,17. Wave breaking, Stokes drift, and Langmuir turbulence are the dominant drivers governing wave-induced vertical mixing in the upper ocean18,19,20,21,22. These mechanisms not only affect the transfer of momentum and heat between the ocean and the atmosphere but also influence the structure and dynamics of the upper ocean, impacting SST variability and the exchange of gases such as CO2 across the air-sea interface23,24. Nevertheless, simultaneous in-situ observations of SST, wind speed, and directional wave spectra remain scarce, particularly during extreme events such as a MHW. The dataset presented here addresses this gap by providing concurrent measurements of SST, wind speed, and wave spectra during the unprecedented 2023 North Atlantic MHW.

This dataset includes high-resolution SST and GPS-based wave and wind observations collected by a drifting buoy off the west coast of Ireland. It comprises continuous measurements from 17 April 2023 to 1 July 2023. This period coincided fortuitously with the peak of the 2023 MHW event, making this data collection unique for advancing research in the field of air-sea interactions. The dataset includes raw and processed files containing SST, directional wave spectra, and wind speed estimates. Such co-located observations are rare and highly valuable for improving coupled ocean-atmosphere models, studying diurnal warming, and validating or assimilating remote sensing and reanalysis products. Similar efforts have demonstrated the value of this kind of datasets for oceanographic research and forecasting applications25,26. Capotondi et al.27, for example, emphasise the importance of high resolution observations for enhancing model development and validation processes of MHW events.

This dataset is then expected to find utility in advancing oceanographic research and enhancing forecasting capabilities in the field. While the present dataset is limited in duration, its coincidence with the 2023 North Atlantic MHW underscores the value of high-resolution observations during extreme events. Sustained deployments of moored and drifting buoys would provide the community with longer-term records essential for monitoring, understanding, and predicting MHWs.

Methods

Instrument and Deployment

Wave, temperature, and wind data were collected using a Spotter wave buoy developed by Sofar Ocean28,29. The instrument was deployed off the coast of Inis Meáin (Aran Islands) on 17 April 2023 on the west coast of Ireland (approximately 53.09°N, 9.61°W). On 1 June 2023, the buoy broke free from its mooring and drifted until it was recovered off the coast of Donegal, Ireland, on 1 July 2023. The Spotter buoy is equipped with a GPS module for wave orbital tracking and a thermistor for SST measurements. The buoy stores raw data internally on an SD card and transmits data nearly in real-time via satellite communication. Three-dimensional wave displacements were measured continuously at 2.5 Hz sampling rate with an accuracy of ±2 cm. SST and buoy location were recorded approximately every minute. Raw data were processed in 30-minute bursts to produce estimates of wind and wave parameters.

Directional Wave Spectrum

The directional wave spectrum, E(f, θ), with f denoting wave frequency and θ wave direction, was derived from the raw buoy time series using a wavelet-based method30. This method produces directional information from the three-dimensional wave displacements by applying a time-frequency wavelet decomposition. Specifically, the EWDM (Extended Wavelet Directional Method) Python toolbox was employed31. Wavelet-based methods have emerged as an alternative to conventional methods and have been proven to produce accurate and robust directional spectra30,32.

Derived Wave Parameters

In addition to the directional wave spectrum, the dataset contains the directional distribution function, which is defined as

where S(f) is the azimuthally-integrated frequency spectrum. Typical wave parameters, derived from the wave spectrum, were estimated. These parameters include the significant wave height, which is defined as

the peak wave period, which was estimated as33

and the eastward and northward components of the Stokes drift, which are defined as34,35

and

respectively. Here, g represents the acceleration due to Earth’s gravity, z is water depth, and k is the wavenumber, which is linked to the wave frequency through the linear dispersion relation. The dataset only includes values of Stokes drift at the surface (z = 0). The frequency resolution is logarithmically distributed with 81 components from 0.03125 Hz to 1 Hz. The directional resolution is Δθ = 5°. The Cartesian convention was adopted for wave directions, i.e., the propagation direction is measured counter-clockwise from the east.

Wind Speed and Direction

Wind speed and direction were determined using the technique presented by Shimura et al.36, which extracts surface wind information from the high-frequency components of the directional wave spectrum. This method is based on the equilibrium range concept introduced by Phillips37, which establishes a local balance between wind input and dissipation. In this range, the wave energy is proportional to S(f) ∝ u*f−4. This relationship thus enables the inference of the friction velocity u* and, consequently, the 10-m wind speed U10. Additionally, wind direction is assumed to correspond to the average wave direction within this frequency range. Extensive testing of this approach on multiple datasets has consistently demonstrated positive results38,39,40.

Sea Surface Temperature

SST was measured by the onboard thermistor located near the base of the Spotter hull, approximately 0.15 m below the sea surface. The sensor accuracy is ±0.10 °C with a resolution of ±0.02 °C, covering a range of −5 °C to 50 °C. Temperature data is internally sampled every second and then averaged over 1-minute intervals.

Data Records

The dataset, which has been deposited in Zenodo41, covers the period from 17 April to 1 July 2023, beginning with a fixed nearshore deployment off the coast of Inis Meáin (Aran Islands) and continuing with a drifting phase after the buoy broke free on 1 June 2023. The buoy trajectory fortuitously coincided with the peak of the 2023 North Atlantic MHW. The dataset includes multiple data files in different formats. The raw 1-minute-resolution time series of SST and buoy location are available in CSV (comma separated values) format. For the 30-minute directional wave spectra, significant wave height, peak wave period, surface Stokes drift, wind speed and wind direction, the data is provided in NetCDF format. Additional auxiliary files that support the validation of the measured SST are included. Each file is self-descriptive and contains metadata specifying the variable names and units, sampling frequency, and conventions, in compliance with the CF standards. A summarised description is presented in Table 1.

A description of the variables provided in the NetCDF file processed-wave-spectra-30min.nc is presented in Table 2. These variables include the directional wave spectra, wind and wave parameters derived from the buoy data. The units and detailed descriptions of each variable are outlined to facilitate a better understanding of the dataset and its components.

Technical Validation

The accuracy of Spotter in-situ SST measurements was assessed by comparing them with three widely-used SST datasets: ERA5, GLORYS, and OSTIA. These datasets provide SST estimates with different spatial and temporal resolutions and diverse nature (models, satellite, in-situ). ERA542 is a global reanalysis from ECMWF that blends model output with observations at 0.25° resolution. GLORYS43 is a 1/12° eddy-resolving ocean reanalysis from CMEMS based on NEMO ocean model, assimilating satellite and in-situ observations. OSTIA44 provides daily 0.05° resolution maps of foundation SST and sea ice, merging satellite and in-situ data while filtering out diurnal variability. Wind speed and direction were compared against ERA5, as it was the only available source providing wind estimates.

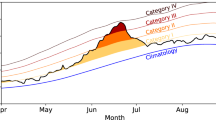

Figure 2a shows a comparison between the in-situ observations and co-located daily SST estimates from ERA5, GLORYS, and OSTIA. The observed SST (1-minute resolution, shown in light red) captures high-frequency variability that is smoothed out in the daily-averaged products. Despite this, the three reference datasets closely follow the general evolution of the observed SST, specifically the onset and peak of the 2023 MHW event. Wind speed and wind direction are shown in Fig. 2b and 2c, respectively. The observed wind estimates generally agree well with the corresponding reanalysis, although the lower variability in the reanalysis fails to capture the real magnitude of extreme values. Note that the overlap between ERA5 and the in-situ records was only available after the buoy broke free on 1 June 2023; prior to this, the buoy position fell on a land grid point in the reanalysis due to its nearshore location.

Table 3 summarises the comparison statistics between observations and various model or reanalysis datasets for SST, wind speed and wind components. In-situ observations were aggregated to daily values to match the reanalysis and compute performance metrics. Correlations for SST are very high across all datasets, exceeding 0.92, with OSTIA performing best (r = 0.98, RMSE = 0.41°C, bias = − 0.04 °C). ERA5 SST also shows strong agreement (r = 0.92, RMSE = 0.42 °C) with a slight cold bias. Wind speed from ERA5 correlates well with observations (r = 0.93), but shows larger RMSE and a small negative bias. The eastward (u) and northward (v) components of ERA5 wind exhibit high correlations (r = 0.92 and r = 0.94, respectively) with moderate RMSE (2.53 and 1.80 m s−1) and small mean biases. Overall, SST products show good agreement with in-situ data, while wind estimates have larger uncertainties, particularly in direction.

To assess the reliability of the wave measurements, the directional spectra are compared against the ResourceCODE database, which serves as a reference for validation. ResourceCODE45,46 is a 30-year hindcast of spectral wave data generated using the WAVEWATCH III phase-averaged wave model47. The spatial domain covers European shelf and offshore waters, from approximately 36°N to 63°N, and from 12°W to 13. 5°E, using a high-resolution unstructured mesh. Spatial resolution ranges from about 10 km offshore, down to approximately 200 m in shallow coastal areas. Forcing is provided by ERA5 winds and tidal currents and water levels from MARS and FES2014 harmonic databases. Temporal resolution is hourly; directional wave spectra and derived parameters are computed at every mesh node. The period covered is 1994–2024.

Figure 3 illustrates the temporal evolution of directional wave spectra derived from Spotter buoy observations and corresponding ResourceCODE hindcast estimates for two representative cases: 4 June 2023 (left panels) and 25 June 2023 (right panels). On 4 June 2023, the buoy measurements reveal a complex wave system with multiple spectral peaks associated with locally growing wind seas propagating toward the south-west and several longer-period swells in different directions. On 25 June 2023, a single, well-developed wave system propagating toward the north-east is observed.

Time evolution of directional wave spectra on 4 June 2023 (columns 1–2) and 25 June 2023 (columns 3-4). Columns 1 and 3 show Spotter buoy observations, while columns 2 and 4 display the corresponding ResourceCODE hindcast estimates. Rows represent the temporal progression of the spectral distribution. Colours indicate wave energy density normalised by the maximum value at each time step, and black arrows denote wind direction, with their length scaled to wind speed.

In both cases, the observed and modelled spectra show good agreement. The ResourceCODE hindcast reproduces the overall structure of the observed spectra, particularly the dominant wave directions and their alignment with wind forcing, as indicated by the arrows. However, the main differences are evident in the spectral energy distribution: the hindcast produces coarser patterns due to the lower resolution whereas the buoy spectral densities are generally smoother. Some low-frequency noise (>20 s period) is apparent in the buoy measurements, especially for the 4 June. This can be attributed to limitations of the buoy-derived wave spectra.

Numerical wave models, as they resolve global and regional wave evolution, are able to capture and track local and remote wave systems over large distances, producing a good representation of the evolution of the directional spectrum. The buoy measurements represent only a single location at any given time. However, they are consistent with these wave systems. Some differences are expected due to the local nature of the observations and known measurement and modelling limitations, but the comparison confirms that the buoy data are reliable and align with the large-scale wave field.

The strong agreement evidenced in this comparison provides confidence in the consistency and reliability of the in-situ measurements presented in this dataset. Beyond validating the data quality, it also underscores their added value for capturing fine-scale and short-term variability in SST, wind, and wave conditions that are often smoothed or underrepresented in reanalysis products. This highlights the relevance of maintaining such observations as a complement to large-scale datasets, particularly for advancing understanding of MHWs and improving model evaluation.

Data availability

The complete dataset is available at Zenodo and can be accessed via the https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15831373. External SST products used for validation were obtained from publicly available sources: GLORYS and OSTIA datasets are accessible via the Copernicus Marine Service (https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/), and ERA5 reanalysis is available through the Copernicus Climate Data Store (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/). ResourceCODE hindcast can be accessed upon registration at https://resourcecode.ifremer.fr/.

Code availability

The directional wave spectra were computed using the EWDM Python software, available at https://github.com/dspelaez/extended-wdm/. Wind speed and related parameters were estimated following the method implemented in the roguewave package developed by Sofar Ocean, which is available at https://github.com/sofarocean/roguewave/.

References

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Progress in Oceanography 141, 227–238 (2016).

Meehl, G. A. & Tebaldi, C. More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science 305, 994–997 (2004).

Shlesinger, T. & van Woesik, R. Oceanic differences in coral-bleaching responses to marine heatwaves. Science of the Total Environment 871, 162113 (2023).

Smale, D. A. et al. Marine heatwaves threaten global biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services. Nature Climate Change 9, 306–312 (2019).

Lacheheb, M., Noy, I. & Kahui, V. Marine heatwaves and commercial fishing in New Zealand. Science of the Total Environment 954, 176558 (2024).

Li, C., Burger, F. A., Raible, C. C. & Frölicher, T. L. Observed Regional Impacts of Marine Heatwaves on Sea-Air CO2 Exchange. Geophysical Research Letters 51, e2024GL110379 (2024).

McCarthy, G. D. et al. The marine heatwave west of Ireland in June 2023. Weather 78, 321–323 (2023).

Berthou, S. et al. Exceptional atmospheric conditions in June 2023 generated a northwest European marine heatwave which contributed to breaking land temperature records. Communications Earth & Environment 5, 1–11 (2024).

England, M. H. et al. Drivers of the extreme North Atlantic marine heatwave during 2023. Nature 1–8 (2025).

Guinaldo, T., Cassou, C., Sallée, J.-B. & Liné, A. Internal variability effect doped by climate change drove the 2023 marine heat extreme in the North Atlantic. Communications Earth & Environment 6, 1–11 (2025).

Ward, B. Near-surface ocean temperature. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 111 (2006).

Veron, F., Melville, W. K. & Lenain, L. Wave-Coherent Air–Sea Heat Flux. Journal of Physical Oceanography (2008).

Janssen, P. A. et al. Air-sea interaction and surface waves (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reading, UK, 2013).

Donelan, M.Air-sea interaction (Cambridge., 1990).

Babanin, A. V. Ocean Waves in Large-Scale Air-Sea Weather and Climate Systems. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 128, e2023JC019633 (2023).

Belcher, S. E. et al. A global perspective on Langmuir turbulence in the ocean surface boundary layer. Geophysical Research Letters 39 (2012).

Polton, J. A., Lewis, D. M. & Belcher, S. E. The Role of Wave-Induced Coriolis–Stokes Forcing on the Wind-Driven Mixed Layer. Journal of Physical Oceanography (2005).

Qiao, F. et al. Wave-induced mixing in the upper ocean: Distribution and effects on upper ocean heat content. Geophysical Research Letters 31 (2004).

Fan, Y. & Griffies, S. M. Impacts of Parameterized Langmuir Turbulence and Nonbreaking Wave Mixing in Global Climate Simulations. Journal of Climate (2014).

Noh, Y., Min, H. S. & Raasch, S. Large Eddy Simulation of the Ocean Mixed Layer: The Effects of Wave Breaking and Langmuir Circulation. Journal of Physical Oceanography 34, 720–735 (2004).

D’Asaro, E. A. et al. Quantifying upper ocean turbulence driven by surface waves. Geophysical Research Letters 41, 102–107 (2014).

Rascle, N., Chapron, B., Ardhuin, F. & Soloviev, A. A note on the direct injection of turbulence by breaking waves. Ocean Modelling 70, 145–151 (2013).

Deike, L. Mass Transfer at the Ocean–Atmosphere Interface: The Role of Wave Breaking, Droplets, and Bubbles. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 54, 191–224 (2022).

Deike, L. & Melville, W. K. Gas Transfer by Breaking Waves. Geophysical Research Letters 45 (2018).

Cavaleri, L. et al. 45 years of directional wave recorded data at the Acqua Alta oceanographic tower. Scientific Data 12, 224 (2025).

McComb, P., Garrett, S., Durrant, T. & Perez, J. Directional wave buoy data measured near Campbell Island, New Zealand. Scientific Data 8, 239 (2021).

Capotondi, A. et al. A global overview of marine heatwaves in a changing climate. Communications Earth & Environment 5, 1–17 (2024).

Raghukumar, K., Chang, G., Spada, F. & Jannsen, T. Directional Spectrum Measurements by the Spotter: A new Developed Wave Buoy. In Ocean Waves Workshop, 5 (2019).

Raghukumar, K. et al. Performance Characteristics of “Spotter,” a Newly Developed Real-Time Wave Measurement Buoy. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 36, 1127–1141 (2019).

Peláez-Zapata, D., Pakrashi, V. & Dias, F. Ocean Wave Directional Distribution from GPS Buoy Observations off the West Coast of Ireland: Assessment of a Wavelet-Based Method. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology (2024).

Peláez-Zapata, D. & Dias, F. EWDM: A wavelet-based method for estimating directional spectra of ocean waves. Journal of Open Source Software 10, 7942 (2025).

Donelan, M., Babanin, A., Sanina, E. & Chalikov, D. A comparison of methods for estimating directional spectra of surface waves. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 120, 5040–5053 (2015).

Young, I. The determination of confidence limits associated with estimates of the spectral peak frequency. Ocean Engineering 22, 669–686 (1995).

Breivik, Ø. & Christensen, K. H. A Combined Stokes Drift Profile under Swell and Wind Sea. Journal of Physical Oceanography 50, 2819–2833 (2020).

van den Bremer, T. S. & Breivik, Ø. Stokes drift. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 376, 20170104 (2018).

Shimura, T., Mori, N., Baba, Y. & Miyashita, T. Ocean Surface Wind Estimation From Waves Based on Small GPS Buoy Observations in a Bay and the Open Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 127, e2022JC018786 (2022).

Phillips, O. M. Spectral and statistical properties of the equilibrium range in wind-generated gravity waves. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 156, 505 (1985).

Thomson, J. et al. Waves and the equilibrium range at Ocean Weather Station P. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 118, 5951–5962 (2013).

Voermans, J. J., Smit, P. B., Janssen, T. T. & Babanin, A. V. Estimating Wind Speed and Direction Using Wave Spectra. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 125 (2020).

Dorsay, C., Egan, G., Houghton, I., Hegermiller, C. & Smit, P. B. Proxy Observations of Surface Wind from a Globally Distributed Network of Wave Buoys. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology (2023).

Peláez-Zapata, D. Sea Surface Temperature and Directional Wave Spectra During the 2023 Marine Heatwave in the North Atlantic. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15831373 (2025).

Copernicus Climate Change Service. ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47 (2018).

Copernicus Marine Service. Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis. https://resources.marine.copernicus.eu/product-detail/GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030/INFORMATION (2018).

Copernicus Marine Service. Global Ocean OSTIA Sea Surface Temperature and Sea Ice Reprocessed. https://resources.marine.copernicus.eu/product-detail/SST_GLO_SST_L4_REP_OBSERVATIONS_010_011/INFORMATION (2015)

Accensi, M., Alday Gonzalez, M. F. & Maisondieu, C. ResourceCODE - resource characterization to reduce the cost of energy through coordinated data enterprise. Database user manual. Tech. Rep., ResourceCode Marine Data Toolbox (2022).

Raillard, N. et al. RESOURCECODE: A Python package for statistical analysis of sea-state hindcast data. Journal of Open Source Software 8, 4366 (2023).

The WAVEWATCH III® Development Group. User manual and system documentation of WAVEWATCH III® version 5.16. Tech. Rep. Tech. Note 329, NOAA / NWS / NCEP / MMAB (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the EU Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant Agreement 833125-HIGHWAVE). The authors acknowledge Arnaud Disant for his support with the buoy deployment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.P.-Z. processed the data and wrote the original draft. B.W. and F.D. contributed equally to the writing and editing of the paper. All authors contributed equally to the conception and development of the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peláez-Zapata, D., Ward, B. & Dias, F. Sea Surface Temperature and Directional Wave Spectra During the 2023 Marine Heatwave in the North Atlantic. Sci Data 12, 2025 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06268-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06268-y