Abstract

The tea tussock moth, Euproctis pseudoconspersa, is one of the most notorious tea plant pests globally. Herein, we assembled a high-quality chromosome level genome of E. pseudoconspersa using a combination of PacBio HiFi sequencing and Hi-C scaffolding. The genome size was 374.29 Mb and 99.94% of the assembled sequences were anchored onto 23 chromosomes with a contig N50 of 15.29 Mb and scaffold N50 of 16.84 Mb. The BUSCO completeness of the assembly was estimated to be 98.69%. The genome contained 132.74 Mb repeat sequences and 12 371 protein-coding genes. This high-quality genome provides a significant genetic resource for analyses of phylogenetic relationships and moth evolution, contributing to the development of pest management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The tea tussock moth, Euproctis pseudoconspersa, is an extremely destructive chewing pest found in tea plantations in China, Japan, and Korea1. This species has high fecundity and its voracious larvae heavily consume the leaves and shoots of tea plants, consequently causing severe losses in both yield and quality. Furthermore, its urticating setae cause serious skin allergic reactions in humans2. Currently, chemical control remains the primary method for managing tea tussock moth infestations. The extensive use of chemical pesticides poses a series of serious problems, including ecological and environmental destruction, threats to the health of tea drinkers, and insecticide resistance. Sex pheromone-based pest management technology, which is eco-friendly and more targeted at specific pests, is used to monitor and control insect pests3. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms and specificity principles underlying pest sex pheromone communication can provide a theoretical foundation for the development of sex attractants4,5.

In addition to their economic importance, sex pheromones play key roles in reproduction and are associated with reproductive isolation and species differentiation6. Based on their chemical structures, moth sex pheromones can be classified into four types. Among these, Type III sex pheromones are rare and have evolved independently several times in several lepidopteran families7,8. Owing to the lack of experimental materials, no draft genome of moths producing Type III sex pheromones is available. The tea tussock moth, which produces Type III sex pheromones (10,14-dimethyl-pentadecyl isobutyrate and 14-methylpentadecyl isobutyrate), is an ideal candidate for the evolutionary analysis of type III sex pheromone moths1.

Whole-genome sequencing is a fundamental tool for studying evolution and provides a complete set of gene resources, contributing to the development of management strategies9,10. In the present study, we assembled a chromosome-level genome of E. pseudoconspersa using a combination of PacBio HiFi sequencing and high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technology. This high-quality chromosome-level genome provides a valuable resource for research on the biology, behavior, and genetic evolution of E. pseudoconspersa.

Methods

Insect collection and sequencing

E. pseudoconspersa larvae were obtained from tea plantations of the Fujian Tianhu Tea Industry Co., Ltd. (120.19°E,27.10°N). Larvae were reared on fresh tea shoots under laboratory conditions at a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C, relative humidity of 65% ± 10%, and under a 14:10 h (light:dark) photoperiod11. Genomic DNA was extracted from a female adult using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The integrity and purity of extracted DNA was monitored on 1% agarose gels and using a NanoDrop™ One UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), respectively. Genomic DNA was sheared in G-tubes (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA) and concentrated using AMPure PB magnetic beads.

Two libraries were constructed for genome sequencing. A short-read sequencing library was constructed using a TruSeq Nano DNA HT Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq X platform at Grand Omics Biosciences Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). The PacBio SMRT bell library was constructed using the SMRTbell® prep kit 3.0 (PacBio, Menlo Park, CA, USA) and sequenced using the PacBio Revio equipment at GrandOmics Biosciences Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). In total, 66.38 and 11.92 Gb of clean data were generated from the Illumina paired-end and PacBio libraries, corresponding to 176.43 × and 31.23 × coverage of the genome, respectively (Table 1).

For Hi-C sequencing, a library was constructed following a standard library preparation protocol using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Beijing, China). The purified DNA was digested with DpnII. Biotinylated nucleotides were used to repair the tails and ligated DNA was sheared to a length of 400 bp. The Hi-C library was sequenced on the MGISEQ-T7 platform. Finally, a total of 56.04 Gb Hi-C clean reads were obtained with approximately 149.67 × coverage of the genome (Table 1).

Genome survey and assembly

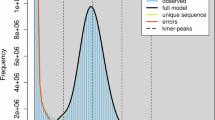

Before genome assembly, k-mer (K = 17) analysis was performed using Illumina DNA data to estimate the genome size and heterozygosity12. The estimated genome size was 368.76 Mb with a heterozygosity of 0.70% (Fig. 1). For de novo genome assembly, raw sequencing data produced by the Pacific Bioscience Sequel were processed using SMRTlink (v8.0) with default parameters. The high quality region finder algorithm was employed to identify the longest regions with single-molecule enzymatic activity. Low-quality regions were filtered out based on the signal-to-noise ratio. After quality control13, the total data volume was 11.92 Gb, comprising 678 097 reads with a read N50 of 18.03 kb. The filtered PacBio HiFi reads were used to produce a preliminary assembly using Hifiasm (v0.19)14,15,16. To discard potentially redundant contigs and generate a draft genome assembly, the contigs were polished with NextPolish (v1.2.4) using Illumina short reads with default parameters17.

Karyotyping and Hi-C scaffolding

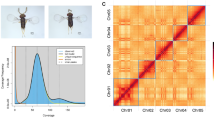

The chromosome number was determined using Giemsa staining of testicular samples from male adults at Hangzhou Kayou Taipu Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). A total of 22 chromosomes were identified in these sperm samples (Fig. 2a,b). Because genomic sequencing was performed using a female adult, which contains Z and W sex chromosomes, the chromosome number was set to 23 for Hi-C scaffolding to enable assembly of the female-specific W chromosome. Draft genome sequences were assembled at the chromosome level using Hi-C scaffolding13,18,19,20. Uniquely mapped paired-end reads were further processed using HiC-Pro (v2.8.1)21 to filter invalid read pairs, including dangling-end, self-cycle, religation, and dumped pairs. In total, 91 347 701 valid interaction pairs were further clustered, and the scaffolds were ordered and oriented onto chromosomes using LACHESIS with the following parameters: CLUSTER_MIN_RE_SITES = 100, CLUSTER_MAX_LINK_DENSITY = 2.5, CLUSTER NONINFORMATIVE RATIO = 1.4, ORDER MIN N RES IN TRUNK = 60, and ORDER MIN N RES IN SHREDS = 60. Finally, 41 scaffolds were anchored onto 23 chromosomes, with a total assembly length of 374.29 Mb, representing 99.94% of the draft genome assembly (Fig. 2c,d). The scaffold/contig N50 was 16.84/15.29 Mb (Tables 2, 3).

Karyotyping and overview of the genomic landscape of Euproctis pseudoconspersa genome. (a) and (b) The chromosomes were identified in the sperm. (c) The heatmap of chromosome interactions of E. pseudoconspersa genome (resolution = 100 Kb). The colour demonstrates the intensity of the interaction from white (low) to red (high). (d) Circos plot of distribution in E. pseudoconspersa genome, which circle I-VII indicated GC content, protein coding genes counts, density of repeat contents DNA transposons, density of repeat contents LINEs and long interspersed elements, density of repeat contents SINEs and short interspersed repeats elements, density of repeat contents LTR and long terminal repeat elements, density of simple repeats of each respective chromosome.

Genomic repeat annotation

First, tandem repeats (TRs) were annotated using GMATA (v2.2)22 to identify simple repeat sequences, while Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF) (v4.07b)23 was used to recognize all tandem repeat elements across the genome. To identify transposable elements (TE), an ab inito repeat library for E. pseudoconspersa was predicted using MITE-hunter (-n 20 -P 0.2 -c 3)24 and RepeatModeler (v1.0.11)25,26,27,28 with default parameters. Subsequently, the predicted repeats were classified via alignment using TEclass Repbase (http://www.girinst.org/repbase)29. RepeatMasker (v1.331)28 was used to identify TEs via homology searching against the de novo repeat and Repbase TE libraries. In total, 126.73 Mb of TE sequences were identified, accounting for 33.86% of the genome assembly, including LTR (4.51%), LINE (12.16%), SINE (1.95%), DNA (8.5%), RC (6.4%), and MITE (0.34%) elements (Table 4).

Gene prediction

Gene prediction was performed using three strategies: homolog-based, transcriptome-based, and ab initio prediction. Homolog-based prediction was conducted using GeMoMa (v1.6.1)30 to align homologous peptides from five lepidopteran insects (Bombyx mori31, Spodoptera litura32, Plutella xylostella33, Papilio xuthus34, and Danaus plexippus35) and Drosophila melanogaster. For transcriptome-based prediction, RNA sequencing data were derived from the antennae, pheromone glands, heads, and bodies of 2-d-old mature virgin female adults and from the antennae, heads, and bodies of 2-d-old mature virgin male adults (accession numbers: SRR31971029-SRR31971049)11. The filtered RNA-seq reads were aligned to the reference genome using STAR (v2.7.3a)36. The transcripts were then assembled using StringTie (v1.3.4 d), and open reading frames were predicted using PASA (v2.3.3)30. Augustus (v3.3.1) with default parameters was used for ab initio gene prediction37. Finally, a unified gene model was predicted by integrating the gene sets obtained from the three methods using EVidenceModeler (v1.1.1)30. In total, 12 371 protein-coding genes were identified in the E. pseudoconspersa genome (Table 5).

Functional annotation of gene models

To annotate the functions of the protein-coding genes, the predicted genes were aligned against various databases, including SwissProt, NR, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, EuKaryotic Orthologous Groups, and Gene Ontology (GO). Putative domains and GO terms of the genes were identified using the InterProScan program with default parameters. BLASTp was used to search the remaining four databases. The results of the five database searches were concatenated (Table 5).

Data Records

The raw NGS data of the E. pseudoconspersa genome were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1299575. The RNA-Seq data are available under Bioproject PRJNA1198692. The final assembled E. pseudoconspersa genome was deposited in the China National GeneBank DataBase under the accession number CNA0509021. Genome assembly and annotation files were deposited in Figshare database.

Technical Validation

The completeness of the assembly was evaluated using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) v4.0.538 (version of the reference database: -l lepidoptera_odb10 -g genome) and Core Eukaryotic Gene Mapping Approach (CEGMA) v239,40,41,42. The analysis identified 98.69% complete BUSCOs (98.07% single-copy BUSCOs and 0.062% duplicated BUSCOs) and 96.77% core genes. To evaluate the accuracy of the assembly, all Illumina paired-end reads were mapped to the draft assembly using the Burrows–Wheeler aligner (BWA) v0.7.1243, and the mapping rate and genome coverage were assessed using SAMtools v0.1.444. The base accuracy of the assembly was calculated using BCFtools v1.8.045. The results showed that 99.9% of Illumina paired-end reads mapped to the draft assembly. These results suggested that the assembled genome was highly complete and accurate.

The Hi-C heatmap showed that the interaction intensity at diagonal positions was higher than that at nondiagonal positions (Fig. 1c), indirectly confirming the accuracy of the chromosome assembly.

Data availability

The Raw data from Illumina, PacBio HiFi sequencing, and Hi-C sequencing of the E. pseudoconspersa genome were available under the accession numbers SRR3499916846, SRR3499916947, and SRR3499917048. Transcriptome data were available with accession numbers SRR31971029-SRR3197104949,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69. The final chromosome assembly were available under the accession number CNA050902170. Genome assembly and annotation files are available in Figshare database71.

Code availability

All software and pipelines were executed according to the manual and protocols of the published bioinformatics tools. The version and code/parameters of the software used are described in the Methods section. No specific code or script was used in this work.

References

Wakamura, S., Yasuda, T., Ichikawa, A., Fukumoto, T. & Mochizuki, F. Sex attractant pheromone of the tea tussock moth, Euproctis pseudoconspersa (Strand) (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae): identification and field attraction. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 29, 403–411, https://doi.org/10.1303/aez.29.403 (1994).

Li, Z.-q. et al. Development of a high-efficiency sex pheromone formula to control Euproctis pseudoconspersa. J Integr Agr 22, 195–201, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2022.08.113 (2023).

Cui, G. Z. & Zhu, J. J. Pheromone-based pest management in China: past, present, and future prospects. J. Chem. Ecol. 42, 557–570, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-016-0731-x (2016).

Leal, W. S. Odorant reception in insects: roles of receptors, binding proteins, and degrading enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 373–391, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153635 (2013).

Thöming, G. Behavior matters-future need for insect studies on odor-mediated host plant recognition with the aim of making use of allelochemicals for plant protection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 10469–10479, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.1c03593 (2021).

Lofstedt, C., Wahlberg, N. & Millar, J. G. Evolutionary patterns of pheromone diversity in Lepidoptera. Pheromone Communication in Moths: Evolution, Behavior, and Application, 43-78 (2016).

Li, Z.-Q. et al. Chemosensory gene families in Ectropis grisescens and candidates for detection of Type-II sex pheromones. Frontiers in Physiology 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00953 (2017).

Yuvaraj, J. K. et al. Characterization of odorant receptors from a non-ditrysian moth, Eriocrania semipurpurella Sheds light on the origin of sex pheromone receptors in Lepidoptera. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 2733–2746, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx215 (2017).

Yan, J. J. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata. Scientific data 10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-01950-5 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Chouioia cunea Yang, the parasitic wasp of the fall webworm. Scientific data 10, 485, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02388-5 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Transcriptome profiling of Euproctis pseudoconspersa reveals candidate olfactory genes for Type III sex pheromone detection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, 1405 (2025).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 (2011).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Comparison of the two major classes of assembly algorithms: overlap-layout-consensus and de-bruijn-graph. Brief Funct Genomics 11, 25–37, https://doi.org/10.1093/bfgp/elr035 (2012).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021).

Myers, E. W. The fragment assembly string graph. Bioinformatics 21(Suppl 2), ii79–85, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1114 (2005).

Hu, J., Fan, J., Sun, Z. & Liu, S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics 36, 2253–2255, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz891 (2020).

Dekker, J., Rippe, K., Dekker, M. & Kleckner, N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science 295, 1306–1311, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1067799 (2002).

Burton, J. N. et al. Chromosome-scale scaffolding of de novo genome assemblies based on chromatin interactions. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 1119–1125, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2727 (2013).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923 (2012).

Servant, N. et al. HiC-Pro: an optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biol. 16, 259, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0831-x (2015).

Wang, X. & Wang, L. GMATA: An integrated software package for genome-scale SSR mining, marker development and viewing. Front Plant Sci 7, 1350, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01350 (2016).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.2.573 (1999).

Han, Y. & Wessler, S. R. MITE-Hunter: a program for discovering miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements from genomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e199, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq862 (2010).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–268, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm286 (2007).

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 18, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-18 (2008).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: A highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.01310 (2018).

Bedell, J. A., Korf, I. & Gish, W. MaskerAid: a performance enhancement to RepeatMasker. Bioinformatics 16, 1040–1041, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/16.11.1040 (2000).

Abrusán, G., Grundmann, N., DeMester, L. & Makalowski, W. TEclass–a tool for automated classification of unknown eukaryotic transposable elements. Bioinformatics 25, 1329–1330, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp084 (2009).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 9, R7, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7 (2008).

Mita, K. et al. The genome sequence of silkworm, Bombyx mori. DNA Res. 11, 27–35, https://doi.org/10.1093/dnares/11.1.27 (2004).

Cheng, T. et al. Genomic adaptation to polyphagy and insecticides in a major east Asian noctuid pest. Nat Ecol Evol 1, 1747–1756, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0314-4 (2017).

You, M. et al. A heterozygous moth genome provides insights into herbivory and detoxification. Nat. Genet. 45, 220–225, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2524 (2013).

Li, X. et al. Outbred genome sequencing and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in butterflies. Nature communications 6, 8212, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9212 (2015).

Zhan, S., Merlin, C., Boore, J. L. & Reppert, S. M. The monarch butterfly genome yields insights into long-distance migration. Cell 147, 1171–1185, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.052 (2011).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 (2013).

Stanke, M., Diekhans, M., Baertsch, R. & Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24, 637–644, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btn013 (2008).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simão, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO update: Novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4647–4654, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab199 (2021).

Parra, G., Bradnam, K. & Korf, I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics 23, 1061–1067, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071 (2007).

Finn, R. D., Clements, J. & Eddy, S. R. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W29–37, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr367 (2011).

Birney, E. & Durbin, R. Using GeneWise in the Drosophila annotation experiment. Genome Res. 10, 547–548, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.10.4.547 (2000).

Alioto, T., Blanco, E., Parra, G. & Guigó, R. Using geneid to identifygenes. Current protocols in bioinformatics 64, e56, https://doi.org/10.1002/cpbi.56 (2018).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698 (2010).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Danecek, P. & McCarthy, S. A. BCFtools/csq: haplotype-aware variant consequences. Bioinformatics 33, 2037–2039, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btx100 (2017).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR34999168 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR34999169 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR34999170 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971029 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971030 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971031 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971032 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971033 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971034 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971035 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971036 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971037 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971038 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971039 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971040 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971041 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971042 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971043 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971044 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971045 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971046 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971047 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971048 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31971049 (2025).

China National GeneBank DataBase https://db.cngb.org/data_resources/assembly/CNA0509021 (2025).

Figshare database https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29928035 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major Science and Technology Special Projects (202402AE090015), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (CAAS-CSCB-202302), and earmarked funds for the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-19).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L., C.X. and N.L. conceived the project; C.Z., Y.L. and H.Q. performed the experiments; L.W., M.L. and Z.L. performed the bioinformatics analyses; X.C., L.B. and N.F. evaluated the results; Z.L., C.X. and N.L. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, K., Long, Y., Qu, H. et al. Chromosome level genome assembly of tea tussock moth, Euproctis pseudoconspersa. Sci Data 12, 1993 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06275-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06275-z