Abstract

Two recent Quaternary volcanic provinces in Iceland and Tengchong, China were investigated with magnetic susceptibility and geochemistry. Despite their similar age, the two volcanic systems have different tectono–magmatic settings (influencing primary magmatic compositions) and different latitudes (influencing secondary emplacement cooling/weathering histories). We present magnetic susceptibility (k), thermomagnetic susceptibility (k-T), and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) major element analysis of 28 volcanic sites, 10 from Iceland at ~64°N latitude and 18 from Tengchong, China at ~25°N latitude. The k and k-T data may reflect primary magma compositions and secondary post-emplacement cooling and alteration histories. The major element chemistry data (e.g., SiO2, TiO2, MgO, P2O5, etc.) also may reflect magma composition and can be used to calculate the loss on ignition (LOI), chemical index of alteration (CIA), modified index of alteration (MIA), and chemical index of weathering (CIW) that may inform post-emplacement alteration and weathering. Both geophysical and geochemical datasets will provide critical constraints for comparing Quaternary volcanism in terms of both contrasting tectono–magmatic and climatic settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Recent and active volcanoes have influenced human history, presenting both hazards (lava eruptions, ground rifting, landslides, toxic emissions, etc.) as well as benefits (such as cultural influence and agricultural influence)1,2,3. It is therefore important to better understand the nature of young volcanism in different tectono–magmatic settings (influencing primary magma compositions) and thus as well as different climate belts (influencing secondary eruptive cooling/weathering processes), with both affecting eruptive behaviour and thus consequences for volcanic hazards and benefits. Studying young, well-exposed and well-preserved volcanic fields also provides useful analogs for interpreting more ancient volcanic fields in Earth history. In much of the geologic record older than such recent volcanism, volcanostratigraphic sequences are preserved4,5,6 but both their ancient tectono–magmatic settings and paleoclimatic belts are sometimes difficult to establish, but carry important implications for their reflection of tectono–magmatic evolution as well as their implications for their influence on Earth’s surface processes. Thus, studying young volcanic fields where such settings are well constrained is critical.

In this study, two recent, mostly Holocene or late Quaternary, volcanic fields were studied—Iceland and Tengchong (Yunnan province, southern China)—because of their similarity in young age but their contrasts in terms of both tectono–magmatic setting and climate belts. To inform these phenomena, relevant data sets from both locations were acquired: magnetic susceptibility (k), thermomagnetic susceptibility (k-T), major element geochemistry (e.g., SiO2, TiO2, MgO, P2O5, etc.) and associated indices of alteration and weathering including the loss on ignition (LOI), chemical index of alteration (CIA), modified index of alteration (MIA), and chemical index of weathering (CIW). The similarities and differences between Iceland and Tengchong can potentially provide new insights into both how primary magma compositions and secondary eruptive cooling/weathering processes affect eruptive behaviours and histories affecting human hazards and benefits, as well as informing the interpretation of more ancient volcanic fields in Earth’s deeper past.

Methods

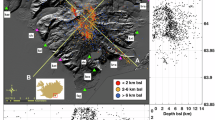

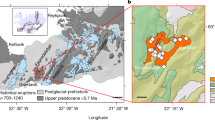

Sampling of volcanic fields

Two recent, mostly Holocene or late Quaternary, volcanic fields were studied: Iceland and Tengchong (Yunnan province, southern China). Iceland volcanism is a combination of its being positioned above a mantle plume as well as its being along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge7. Tengchong occurs along mantle-depth transcurrent faults east of the India–Eurasia collision related to escape tectonics8. These different tectono-magmatic settings influence their primary magma compositions. Iceland occurs at high latitudes (~64°N) whereas Tengchong occurs at low midlatitudes (~25°N). These different latitudes and thus contrasting climate belts influence their secondary emplacement cooling/weathering processes. We analyzed 10 bulk samples from Iceland and 18 bulk samples from Tengchong volcanic field.

Magnetic susceptibility

Magnetic susceptibility was measured in situ on the outcrop with a handheld Terraplus KT-10R magnetic susceptibility meter. Given that the handheld meter normalizes by volume. Porosity of the rocks and irregularities in the surface may contribute to deviations in the measurements. To minimize these effects, we selected the freshest outcrops possible and chose flat surfaces for measurement. Multiple measurements were taken across different outcrop surfaces to obtain a more representative average for each outcrop. Samples are taken in similar massive lithologies at the same outcrop where the measurements were made, but they were not always the identical sample. The average and standard deviation were calculated for n ≥ 3 measurements at each sampling spot.

Thermomagnetic susceptibility

Samples were also collected for laboratory analysis. Thermomagnetic susceptibility (kT) experiments were conducted to identify the magnetic mineralogy accounting for the measured ranges of susceptibility. These experiments were performed using an AGICO MFK2-FA KappaBridge instrument at the “MagMin” laboratory of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS) in Beijing. A 0.3 g aliquot of the powdered sample was then heated to 700 °C and subsequently cooled to 50°C with a rate of ~12°C/min to obtain both the heating and cooling curves. The applied field was 200 A/m and the operating frequency was 976 Hz. To prevent oxidation during heating and cooling, the experiments were conducted under an argon atmosphere.

Calculation of curie point temperatures

It is practically impossible to determine the Curie temperature (Tc) with absolute precision. To achieve the most accurate estimation possible, several commonly used methods were employed in a comprehensive manner. The Curie temperature is primarily identified using the first derivative method, which detects the peak in the first derivative of the magnetic susceptibility–temperature (k-T) curve9. However, in some samples, the peaks of the kT derivative curves appear over a broad temperature range. In such cases, the lowest peak or the intersection point based on inverse susceptibility is typically used to determine Tc. When the temperature exceeds Tc, the magnetic susceptibility is governed by the paramagnetic behavior of the material, where the Curie–Weiss law applies:

Accordingly, in a 1/k versus T plot, Tc corresponds to the lowest temperature limit of the linear trend observed over a significant temperature range10.

Major element geochemistry

Major element analysis was conducted to investigate geochemical composition and alteration states. We used X-ray fluorescence (XRF) for major elements analysis. Major element data for whole-rock samples were obtained by X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry on fused glass discs using a PANalytical AXIOS Minerals instrument at the Rock-Mineral Preparation and Analysis Lab, the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS) in Beijing. The PANalytical AXIOS Minerals instrument is equipped with a Rh anode X-ray tube and 4 kW excitation power is a sequential instrument with a single goniometer-based measuring channel covering the complete elemental measurement range from F to U in the concentration range from 1.0 ppm to % level, determined in vacuum media. Loss on ignition (LOI) was measured as the weight loss of the samples, which was obtained independently by igniting 0.5 g dry sample aliquot in a porcelain crucible for 1.5 h at 1,000 °C in a muffle furnace.

Calculation of indices of alteration and weathering

The Chemical Index of Alteration (CIA) (refs. 11,12) is useful for evaluating the chemical weathering degree of our volcanic samples. High CIA values reflect the removal of mobile cations (e.g., Ca2+, Na+, K+) relative to stable residual constituents (Al3+) during chemical weathering. The CIA (Chemical Index of Alteration) is calculated using the formula:

Similarly, the MIA (Modified Index of Alteration) is also an index of the intensity of chemical weathering, MIA values include Fe2O3 and MgO to better reflect weathering in mafic or ultramafic rocks13. The calculation of MIA depends on the environment:

In an oxidizing environment, Fe is usually retained by the formation of highly insoluble ferric iron [Fe3+] oxides or oxyhydroxides. Total Fe is considered an immobile element along with Al.

In reducing environment, ferrous iron [Fe2+] can be mobile, and total Fe is considered a mobile element.

The CIW (Chemical Index of Weathering) is similar to CIA value but excludes K2O, and is calculated as14,15:

All of these three indices use the molar ratios of the major element oxides by converting the wt.% concentrations into moles. The molar Cao is corrected for the presence of carbonate and apatite for the CIA (e.g., ref. 16) to consider only the silicate-bound Ca (CaO*).

Data Records

The database is openly available in the Figshare data repository17 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28737404). It includes an Excel file containing three sheets (Data Table 1–3) and 28 sets of magnetic curves (Data Figs. 1–28), as well as a raw thermomagnetic susceptibility data file (Raw Data) related to the magnetic susceptibility and geochemistry of samples collected from Tengchong and Iceland. Data Table 1 contains basic sample information. Data Table 2 presents field and laboratory measurements of magnetic susceptibility (k) and the Curie temperature(s) obtained from thermomagnetic susceptibility (k-T) experiments. Data Table 3 provides major element geochemical data, along with calculated weathering and alteration indices.

Data Table 1. This table provides detailed locality information for each sample. The table includes the following column headings: (1) sample or site name; (2) volcano name or geological unit; (3) GPS coordinates (latitude and longitude); and (4) lithology. Additional notes are at the bottom of the table.

Data Table 2. This table contains both field and laboratory magnetic measurements. The first row lists the column headings, which include: (1) sample site name; (2) magnetic susceptibility measured in the field using a handheld KT-10 meter; (3) the number of individual measurements taken at each sampling spot; (4) the standard deviation of the field magnetic susceptibility values; and (5) the Curie temperature(s) identified from laboratory thermomagnetic (k-T) experiments. Figure 1 shows a bi-histogram of the magnetic susceptibility data from both locations.

Data Table 3. The geochemical data are compiled in Data Table 3. Eight samples from Icelandic volcanic rocks are basalt, while the other two are trachyte-dacite (using TAS diagram for classification18). Tengchong samples, according to geochemical results, range from trachy-basalt to trachy-dacite. The table includes: (1) sample site name; (2) lithological classification of each sample; (3)–(13) weight percentages of major oxides, including SiO₂, TiO₂, Al₂O₃, TFe₂O₃, MnO, MgO, CaO, Na₂O, K₂O, and P₂O₅; (14) loss on ignition (LOI); (15) corrected CaO content, representing CaO in silicate minerals only; (16) Chemical Index of Alteration (CIA); (17) Modified Index of Alteration (MIA) under oxidizing conditions; (18) MIA under reducing conditions; and (19) Chemical Index of Weathering (CIW). Figure 2 shows a bi-histogram of the chemical weathering indices from both locations.

Data figures

The k–T (thermomagnetic) curves for all 28 samples, collected from both Tengchong and Iceland, are presented in Data Figs. 1–28. Each figure displays the heating and cooling curves, with the Curie temperatures marked (see Methods for details). In each plot, the red curve represents the heating process, while the blue curve represents the cooling path.

Raw data

The raw thermomagnetic susceptibility datasets from the experiments are provided in .cur format. These files include all data points recorded during the heating and cooling processes. The reader can open them in Cureval or in any spreadsheet or plotting software. The meaning of each column is as follows: (1) TEMP: Sample temperature during the experiment; (2) TSUSC: Uncorrected total magnetic susceptibility measurement; (3) CSUSC: Corrected magnetic susceptibility for the empty furnace; (4) NSUSC: Normalised corrected susceptibility; (5) BULKS: Bulk susceptibility; (6) FERRT: Total ferromagnetic component susceptibility; (7) FERRB: Bulk ferromagnetic component susceptibility; (8) TIME: Measurement time; (9) EMPTY: Auxiliary data automatically generated by the instrument.

In conclusion, this dataset provides essential magnetic susceptibility measurements alongside detailed major element geochemistry and chemical weathering indices, offering a valuable resource for interpreting ancient volcanic fields. Magnetic susceptibility data reveal mineralogical variations and thermal properties, which are crucial for understanding past volcanic activity and alteration processes. Meanwhile, the geochemical data and weathering indices quantitatively characterize chemical changes, providing insights into magmatic evolution and post-eruptive alteration. Together, these complementary datasets enable a comprehensive understanding of magmatic systems, alteration histories, and tectonic influences, supporting broader applications in volcanology, geochemistry, and the study of ancient volcanic provinces.

Technical Validation

Validating magnetic susceptibility

Field measurements of magnetic susceptibility made with the Terraplus KT-10R handheld meter were made after testing against a calibration pad of known susceptibility, ensuring that the meter was functioning reliably.

Validating thermomagnetic susceptibility

A series of meticulous technical procedures were followed during data collection, processing, and analysis to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the results. Samples were powdered using an agate grinding method to minimize contamination. Laboratory measurements of magnetic susceptibility made with the AGICO MFK2-FA Kappabridge instrument were made after testing against a calibration standard of known susceptibility, ensuring that the machine was functioning reliably.

Validating major element geochemistry

The PANalytical AXIOS Minerals instrument used is equipped with a Rh anode X-ray tube and 4 kW excitation power is a sequential instrument with a single goniometer-based measuring channel covering the complete elemental measurement range from F to U in the concentration range from 1.0 ppm to % level, determined in vacuum media. The limits of detection (LOD) and the limits of quantitation (LOQ) of the major elements in experiments are presented in Table 1.

Data availability

The researchers can download this dataset from Figshare17. The dataset includes an Excel file containing three sheets (Data Table 1–3) that separately present the sample locations, magnetic susceptibility data, and major element geochemistry data, as well as a folder containing 28 sets of magnetic curves (Data Figs. 1–28) and another folder with their corresponding raw data (Raw Data). The dataset is freely available for download and sharing, and users are encouraged to integrate it with other datasets and modelling approaches to enhance interpretations of ancient volcanic fields.

Code availability

No custom code was used.

References

Oppenheimer, C. in Mountains of Fire (University of Chicago Press, 2023).

Ludwig, K. A. et al. Science for a risky world–A U.S. Geological Survey plan for risk research and applications. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1444, 57 (2018).

Christiansen, R. L. et al. Preliminary assessment of volcanic and hydrothermal hazards in Yellowstone National Park and vicinity. U.S. Geological Survey Ope-file Report 2007-1071, 94 (2007).

Swanson-Hysell, N. L., Maloof, A. C., Weiss, B. P. & Evans, D. A. D. No asymmetry in geomagnetic reversals recorded by 1.1-billion-year-old Keweenawan basalts. Nature Geoscience 2, 713–717, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo622 (2009).

Lu, K. et al. Widespread magmatic provinces at the onset of the Sturtian snowball Earth. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 594, 117736, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2022.117736 (2022).

Lan, Z. et al. Massive Volcanism May Have Foreshortened the Marinoan Snowball Earth. Geophysical Research Letters 49, e2021GL097156, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL097156 (2022).

Jakobsson, S. P., Jónasson, K. & Sigurdsson, I. A. The three igneous rock series of Iceland. Jökull 58, 117–138 (2008).

Li, N., Zhao, Y.-W., Zhang, L.-Y. & Wang, J.-L. The quaternary eruptive sequence of the Tengchong volcanic group, southwestern China. Lithos 354, 105173, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2019.105173 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Seafloor magnetism under hydrothermal alteration: Insights from magnetomineralogy and magnetic properties of the Southwest Indian Ridge basalts. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 126, e2021JB022646, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JB022646 (2021).

Petrovský, E. & Kapička, A. On determination of the Curie point from thermomagnetic curves. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 111, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004507 (2006).

Nesbitt, H. W. & Young, G. M. Early Proterozoic climates and plate motions inferred from major element chemistry of lutites. nature 299, 715–717, https://doi.org/10.1038/299715a0 (1982).

Nesbitt, H., Young, G., McLennan, S. & Keays, R. Effects of chemical weathering and sorting on the petrogenesis of siliciclastic sediments, with implications for provenance studies. The journal of geology 104, 525–542, https://doi.org/10.1086/629850 (1996).

Babechuk, M., Widdowson, M. & Kamber, B. Quantifying chemical weathering intensity and trace element release from two contrasting basalt profiles, Deccan Traps, India. Chemical Geology 363, 56–75, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.10.027 (2014).

Harnois, L. The CIW index: a new chemical index of weathering. Sedimentary geology 55, 319–322, https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(88)90137-6 (1988).

Óskarsson, B. V., Riishuus, M. S. & Arnalds, Ó. Climate-dependent chemical weathering of volcanic soils in Iceland. Geoderma 189, 635–651, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2012.05.030 (2012).

Fedo, C. M., Wayne Nesbitt, H. & Young, G. M. Unraveling the effects of potassium metasomatism in sedimentary rocks and paleosols, with implications for paleoweathering conditions and provenance. Geology 23, 921–924, 10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0921:UTEOPM>2.3.CO;2 (1995).

Yuwei, Z. & Ross, M. Magnetic susceptibility and geochemistry of young volcanism in Iceland and Tengchong, China. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28737404 (2025).

Middlemost, E. A. Naming materials in the magma/igneous rock system. Earth-science reviews 37, 215–224, https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-8252(94)90029-9 (1994).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank all members who provided help and assistance during the sampling and laboratory work. This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; 42488201), the Strategy Priority Research Program (Category B) of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB0710000), and the President’s International Fellowship Initiative (PIFI; 2021FYC0002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mitchell designed the project and collected the samples. Zhang processed the samples and conducted the analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Mitchell, R.N. Paired magnetic susceptibility and geochemistry of young volcanism in Iceland and Tengchong, China. Sci Data 12, 1985 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06288-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06288-8