Abstract

The United States Water Withdrawals Database (USWWD) provides a standardized compilation of user-level water withdrawal data across 42 US states. USWWD provides time series of water withdrawals at unprecedented spatial and temporal resolutions, encompassing 188,857 unique water users, 353,694 points of diversion and use, and 58,439,412 withdrawal volumes included in 7,524,266 records across various sectors. USWWD integrates diverse state-level data sources, standardizing information on water users, withdrawal locations, volumes, source types, and primary water use categories. The withdrawal data combines both direct measurements and various estimation techniques, reflecting the diverse methods utilized by different state agencies in reporting water usage. USWWD addresses significant gaps in national water use data, enabling researchers to conduct detailed analyses of water withdrawal patterns, trends, and drivers across space, time, and sectors. This granular dataset supports a wide range of applications, including water resource management, planning, and policy development. By providing the most detailed national water use data to date, USWWD facilitates new understanding of how society uses water.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Sustainable management of water resources necessitates that water supplies are sufficient to meet all water demands, including those of the environment1,2,3. However, effective water management in the United States (US) has been hampered by a critical data gap – we know far more about water supply than about who uses water, how much they withdraw, and where and when that water is used. Unlike water supply measurements, which benefit from consistent nationwide monitoring networks, water use data has historically been fragmented, inconsistently collected, and difficult to access2,4.

The lack of spatially and temporally detailed water use data across all sectors of the US economy impedes research, planning, and management of water resources5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Moreover, this lack of water use data has led to significant gaps in our knowledge of water use patterns and trends across different sectors of the economy, as well as our ability to accurately predict future water needs. Recognizing these gaps, there have been efforts in recent years to assess the direct and indirect water footprints across various economic sectors. Notably, Marston et al.4 estimated water footprints for over 500 industries using reported and derived data roughly corresponding to the years 2010–2012. More recently, Lopez et al.14 provided an inventory of water withdrawals for the Upper Colorado River Basin; however, their effort is only limited to diversions of surface water at the points of diversion rather than individual users. Our study builds upon and extends previous such work by providing nationwide time series of user-reported water withdrawal data across all sectors of the economy, spanning from 1906 to 2025 (mean: 2007, median: 2009, standard deviation: 10.8 years) at the individual user level. It is important to note that records in this database represent total water withdrawals rather than consumptive use. As climate change introduces greater variability in precipitation and streamflow, and as population growth, technological advancements, and economic development alter water demands, the need for such comprehensive, standardized water use data becomes increasingly urgent to assess water availability and to develop targeted plans to meet society’s water needs.

The current limitations in water use data stem from two primary challenges. First, water use data is not systematically and consistently collected at the spatial and temporal scales necessary – i.e., sub-annual, user-level measurements of water withdrawals – to inform water resources planning, modelling, and management. Even when detailed, high-quality measurements of water use are collected, there is a wide variation in what gets collected and how it is collected by different stakeholders (e.g., local, state, and federal agencies2,4,9,15). For example, there is wide variance in data collection and reporting requirements across states, including differences in temporal frequency, collection methods, and who is required to report. While some states require all self-supplied water users to report their withdrawals, even if they are zero (such as Utah and Kansas, domestic being exempt in the latter state), others have different single thresholds above which users are required to report, ranging from 10,000 gallons per day (such as Pennsylvania and Tennessee) to 100,000 gallons per day (such as Florida, Georgia, Nevada, Indiana, and Massachusetts) during a specific period of time, usually 30 successive days. The reporting threshold criteria gets more involved in some states, making these thresholds not directly comparable across states. For example, some states implement multiple thresholds based on withdrawal source (e.g., surface water versus groundwater) (e.g., Arkansas) or water use sectors (e.g., Oklahoma). Furthermore, thresholds may vary within a single state depending on location; for example, in Northern Utah County and Cedar Valley, users diverting more than 100 acre-feet per year are required to report, while such thresholds are non-existent or different in other parts of Utah. This variance in the definition of who must report directly impacts the amount of data collected for each state. For detailed information on the specific reporting requirements and thresholds for each state, readers are encouraged to refer to the user notes provided in Table S1. Second, there is not a centralized, nationally consistent data product describing, at the user-level, who uses water, how much they withdraw, and where and when that water is used15. The degree to which high-quality, user-level water use measurements exists, these data are dispersed across dozens of different entities2. Various technical and non-technical (e.g., social16) barriers acting on individual researchers, groups, and organizations to open data sharing further contribute to the fragmented state of water use data.

While the US Geological Survey (USGS) maintains a national water use database through its Water Availability and Use Science Program (WAUSP)17, which contributes to the National Water Census18, these estimates have notable limitations. Historically, USGS estimates were produced only quinquennially at the county level, with restricted sectoral classification and reliance on an opaque mixture of process-based models, static water use coefficients, heuristics, and state agency questionnaires and metered water withdrawals19,20,21,22. The provenance and derivation of their reported data were not always transparent, creating uncertainty about data quality and reliability.

Recently, USGS has begun developing nationally consistent monthly modelled estimates for irrigation, public supply, and thermoelectric water uses at the finer Hydrologic Unit Code 12 (HUC12) subwatershed level23,24,25. However, these aggregated estimates mask critical variations between individual water users, hampering researchers’ ability to understand user-specific patterns and drivers of water use. Furthermore, USGS currently lacks detailed subannual data for several important sectors, including livestock, industrial, mining, and commercial water uses.

While coarse modelled water use estimates fill a critical gap, metered, user-level water use data generally provides the most accurate basis for analysis. Yet, there is a lack of comprehensive metered water withdrawal data across sectors and regions, significantly constraining our ability to investigate critical questions about water demand, sustainability, planning, and management. To address these limitations, we undertook a comprehensive nationwide effort to collect, standardize, and assess the quality of water withdrawal data.

The United States Water Withdrawals Database (USWWD), developed in this study, represents the most detailed standardized compilation of water withdrawal data available across 42 US states. Following the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles26, USWWD provides sufficient documentation and standardization to support broad data utilization. This comprehensive dataset encompasses 188,857 unique water users and includes historical time series of water withdrawals at unprecedented spatial and temporal resolutions. The database includes 58,439,412 withdrawal volumes included in 7,524,266 records. By integrating diverse state-level data sources and standardizing information on water users, withdrawal point of diversion (POD) and place of use (POU), volumes, source types, and primary use categories, USWWD enables researchers to conduct detailed analyses of water withdrawal patterns, trends, and drivers across space, time, and sectors. The database explicitly specifies the estimation or measurement method used for each withdrawal record where available, acknowledging the diverse approaches employed across different jurisdictions to quantify water usage. Here, we refer to water use and water withdrawals synonymously, representing water diverted from a surface water or groundwater source for utilization. The data products developed for USWWD build upon our previous data collection and standardization frameworks27,28 and are summarized in Table 1.

USWWD supports a wide range of applications in water resource management, conservation planning, and modelling. By providing access to user-level water withdrawal data across over 353,000 unique points of diversion or use (Fig. 1), USWWD advances sustainable water management by improving knowledge of US water demand, which is essential for assessing water availability and addressing the water challenges of the 21st century. More specifically, USWWD can improve downscaling of coarser water use estimates, improve and validate process-based models and remote sensing of water use29,30, establish industry-specific water use benchmarks, and assess the role of technology, human decision-making, and other dimensions of water use.

Distribution of points of diversion (PODs) and places of use (POUs) across water use categories and states. The numbers following the category names in the legend indicate the number of unique POD and POU coordinates for each category. The map shows 353,694 unique points from which 335,355 pairs are PODs and 10,563 are POUs and 7,776 are both PODs and POUs, though this represents only a portion of United States Water Withdrawals (USWWD) records, as many lack spatial coordinates. Hatched states have no data, while grey states have USWWD records but do not have associated spatial coordinates.

Methods

We define a water user as an individual person, business, or other legal entity that is required by state law to periodically report their self-supplied water withdrawal from surface water and/or groundwater. A record in our database is a row of data, which includes a user ID, the reporting year, and all other attributes as described in Table 1, Water User Characteristic. A data record can have a maximum of 13 reported volumes, one for each month and one for the annual total. The self-supplied water withdrawal only represents direct water withdrawals by users, not individual deliveries from a water distributor, such as an irrigation district or public water supplier. Some industries, particularly manufacturing, may rely on both self-supplied water withdrawals and municipal water supplies5. Thus, our data may only represent a portion of their overall water use.

Reporting requirements vary by state. Furthermore, water withdrawal records are independently collected and maintained by each state, leading to variations in coverage, duration, completeness, and quality of the records from state to state. These variances are mirrored in USWWD, as it compiles data from these diverse state sources. To address differences in state reporting, our database converts disparate state records into a standardized format, featuring a common set of attributes that are consistently reported across most states. This includes details on water users, withdrawal and/or use locations, withdrawal volumes, source types, and primary water categories. USWWD only encompasses records of user-level water withdrawals in the US that can be made publicly available.

Creation of USWWD involved three main steps: (i) data collection, (ii) data standardization, and (iii) data validation. These are described in the following sections.

Data collection

The data collection process was done separately for each state and started by identifying state agencies that might have the desired data. This identification process was conducted through our existing relationships with local, state, and federal partners, building on the work of previous data collection efforts9,27,28 and by online searches. After identifying potential data sources, we first gathered state water withdrawal data made publicly available online, which was the case for 13 states (Alaska, Arizona, California, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming). Direct links to the program or data source were provided in the text and in the bibliography where possible, and Table S1 provides further details about the data source for the mentioned 13 states and other state sources whose data are included in USWWD. In all cases, direct contact with data-holding agencies was necessary, as data were either not publicly available, partially available (e.g., available for certain years or location within states), or lacked sufficient accessibility (due to download limitations or inadequate metadata). The data acquisition process varied by state, with 11 states requiring formal public records law requests (Table 2) and 31 states providing data through less formal channels (Table 3). Through these procedures, we successfully collected water withdrawal data from 42 states. Table S1 in the Supplementary Information provides the names and website addresses of all contributing organizations.

To standardize and facilitate communication with state agencies, we developed a protocol that outlined the study purpose, described the desired data, and explained why each state agency was being contacted. This protocol explicitly detailed how agencies could assist in developing USWWD through providing water withdrawal data and associated metadata, while emphasizing our commitment to comply with all data-sharing regulations. Each state has different data privacy standards and only data that is already public or that we were explicitly told could be made public comprises USWWD. The complete communication protocol is included as a supplemental document to this manuscript.

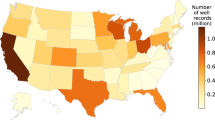

The responses we received from state agencies fell into three categories: (1) States that collect and archive water withdrawal data but cannot share them due to privacy concerns or lack of a coordinating agency (Washington D.C. and Nebraska); (2) States that either do not collect the desired data or only collect it at the headgate/point of diversion (POD) level, i.e., not user-level data (no data: Alabama, Maine, Montana, and Rhode Island; data only at POD level: Idaho, Nevada, and New Mexico); (3) States willing to share all or part of their collected data (remaining 42 states). States can fall into more than one category; for example, some states may collect but cannot share data for certain sectors (category 1) while sharing data for other sectors (category 3), or they may share some user-level data (category 3) while collecting most data at the POD level (category 2). It is important to note that POD-level data not specific to a single water user was outside our study scope as it typically aggregates multiple users rather than providing individual user-level data (with the exception of public water supply utilities, which we considered single users). Among the 42 states in the third category, Colorado and Illinois provided data for only one category (public supply), with Colorado’s other categories being at the POD level and Illinois withholding other categories due to privacy concerns. For the remaining states in the third category, we included all shareable data, though in some cases small portions were unavailable due to records existing only in physical form or being in formats unsuitable for sharing. The number of unique water users reporting water withdrawals within each state ranged from 61 in Colorado to 26,377 in Kansas (Fig. 2).

Data availability and user counts across US states in the United States Water Withdrawals Database (USWWD). Hatched states collect user-level water withdrawal data but restrict public access due to privacy concerns or other limitations. Dotted states either do not collect user-level water withdrawal data or only maintain records at the point of diversion (POD).

During data processing, agencies were again contacted to clarify water use category definitions, whether location data represented POD or POU, and missing information such as volume units. When we found data for a state were hosted by different state agencies, we contacted all data-holding agencies to ensure we had complete data. In such cases (e.g., Florida and Texas), we cited all agencies within a state from which we received data. In some states, multiple organizations work together to produce water withdrawal data. For example, in Utah, the Division of Water Rights collects the data while the Division of Water Resources validates and publishes the data. Furthermore, in some states similar data (e.g., user-level data vs. aggregated data) can be accessed from multiple state agencies. Near project completion, agencies received standardized questions about publication permissions and information needed for comprehensive metadata development. To provide further context about each state data, we added a user’s note section in Table S1 which is based on our direct correspondence with state agencies that provides more context about such details as data provenance and limitations. Many states continuously update water user information, meaning our dataset represents the most current data available at collection time. However, some states noted their records are not routinely updated, potentially missing unreported changes in water use or user status. Table S1 details collection dates by state and primary contacts. Data collection occurred from August 2020 to July 2025, with records collected by the state after our collection dates excluded from USWWD. All states explicitly permitted publication of provided withdrawal records and were given the opportunity to review their data representation in USWWD. Following privacy requests from some states, we excluded sensitive information (water user names, detailed contact information) from all state records to maintain consistency.

Data standardization

We standardized state-level data into a common accessible human- and machine-readable database while preserving original data characteristics. Our data standard maintained important details from each water use record across time and space and water use categories. USWWD attributes are categorized into user information (e.g., water user unique IDs), location information (e.g., water withdrawal coordinates), withdrawal information (e.g., measurement method), withdrawal volume information (e.g., annual and/or monthly withdrawal volume), and flag information for validation purposes (see Table S2).

Due to varying state definitions of water use attributes, our dataset employs broad definitions for each attribute. A crosswalk table (see Table S3) aligns original attribute names from state datasets with USWWD. State agencies provided metadata files defining attributes along with abbreviations and labels. When metadata was unavailable, we contacted relevant state agencies to get clarification on attribute definitions. USWWD incorporates the most commonly reported data attributes across states. Some water use attributes collected by some states but not others were excluded from USWWD to maintain consistency across states.

Varying state data specifications required unique preprocessing steps to prepare datasets for a common standardization workflow. Key steps included combining tables and addressing data structures like multiple tables for different years, counties, or water use categories. We verified column data types, standardized strings, replaced negative value volumes with null values, and removed duplicate rows. Most datasets contained negligible negative value volumes and duplicate rows. We assigned unique IDs to each water user name, which included the state two-letter abbreviation followed by eight-digit numbers starting from 1 for each state. This preprocessing prepared state datasets for the common standardization workflow.

Of the 42 states sharing data, 32 include coordinate information for POD and/or POU. If given the coordinates, we evaluated these coordinates to ensure they all followed the same format and projection system. Most coordinates represented only water user PODs (27 states), though two states only reported POU coordinates and three states reported both POD and POU coordinates. While most coordinates were in geographical coordinate systems, some states used projected systems like Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) or State Plane. We assumed the North American Datum of 1983 (NAD83) for unspecified geographic coordinates and UTM with zone(s) for projected coordinates. We visualized all coordinates in ArcGIS Pro to verify they fell within the appropriate US boundary, state boundary, or specific state region that the coordinates corresponded to.

When coordinate and withdrawal information existed in separate files, they were uniquely associable based on state-provided key columns connecting coordinates to user name and reporting period in the majority of states. Seven states’ coordinate information (Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Ohio), however, was associable by water user name only. This occurred, for example, when users reported withdrawing from multiple PODs but volumes were not subcategorized down to the individual PODs. Importantly, some provided coordinates represented approximate rather than exact locations, for example, in the case of Iowa, coordinates represent average locations of POD and POU.

We used the coordinates of each water use POD and/or POU to add further geographical information to each record. ArcGIS Pro’s spatial join function overlaid coordinate locations with HUC1231 and county32 shapefiles to identify the associated HUC12 and county for each point. We assigned HUC12 codes and county names, as well as the Federal Information Processing System (FIPS) code, to each record. Furthermore, we standardized county names by changing abbreviations and codes to full county names to ensure consistency across states.

Water use categories in USWWD follow modified USGS definitions to accommodate state-level variations in water use category definitions. The categories include: 1) Irrigation - Crop, 2) Irrigation - Other, 3) Irrigation - Golf Courses, 4) Irrigation – Unspecified, 5) Agriculture – Unspecified, 6) Public Supply, 7) Livestock, 8) Aquaculture, 9) Industrial, 10) Commercial, 11) Mining, 12) Power – Hydroelectric, 13) Power – Thermoelectric, 14) Power - Other, 15) Domestic, 16) Remediation, and 17) Sewage Treatment. Two additional categories, Other and Unknown, capture multiple-use cases (for a user) and unspecified or missing categories, respectively. Power – Other encompasses non-thermoelectric and non-hydroelectric sources (e.g., solar) and multiple or unspecified power categories. Irrigation – Unspecified covers records without a known specific irrigation purpose, while Agriculture – Unspecified includes undifferentiated agricultural records that could be crop irrigation, livestock, or aquaculture.

Our crosswalk between state water use categories and our definitions were informed by state documentation, guidance from state agency and USGS staff, and supplemental data like North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes. In a few instances, one-to-one alignment between state and USWWD water use definitions was not possible, resulting in some one-to-many mappings. For example, broad state categories like “Agriculture” were mapped to multiple standardized categories based on state definitions, though precise categorization remained challenging even with state-specific explanations.

Given that energy and agriculture water uses are by far the largest water using sectors in the US4,22, we employed secondary data sources to subcategorize unspecified irrigation, agriculture and power records. Irrigation represents the largest water use category in USWWD, with 4,525,645 of 7,524,266 records (60.1%). However, only 2,402,815 (53.1%) of irrigation records clearly specify crop, golf courses, or other irrigation as their purpose. Similarly, broad state-specified agricultural categories, which could include crop irrigation, stock watering, and aquaculture, account for 221,471 records (2.9%). While power generation comprises just 50,358 records (0.7%), these represent substantial water withdrawal volumes. Of these power records, only 24,590 (48.8%) specify the generation type (e.g., thermoelectric, hydroelectric).

To assign unspecified irrigation, agriculture, and power records in USWWD to more specific use categories, we used location-based methods. For irrigation and agriculture, we spatially joined records with Regrid’s Nationwide U.S. Premium Schema Parcel Dataset33 to identify properties with cropland or pastureland overlaying or near POD or POU (see Table S4). Water use record coordinates that did not directly overlap with land parcels were categorized based on their proximity (within a 100 meters) to relevant parcels. Golf course irrigation was classified using Open Street Map34 data. Records meeting multiple criteria were assigned to multiple categories to be conservative. Power subcategorization utilized the Energy Information Administration (EIA) plant database35, matching plant names, counties, and primary fuel type information (see Table S5) between USWWD and EIA datasets. Multiple fuel types were assigned when a plant had several primary sources. This subcategorization required coordinate information for irrigation and agriculture records (available for 2,129,991 of 2,344,301 records, 90.8%) and user name and county information for power records (available for all unspecified power records). Figure 3 compares the number of records originally assigned to each category and the number assigned after further data processing.

Subcategorization results of unspecified irrigation, agriculture, and power generation records. Original (red bars) and after subcategorization (blue bars) record counts in the United States Water Withdrawals Database (USWWD) for six categories: Irrigation - Crop, Irrigation - Golf Courses, Livestock, Aquaculture, Thermoelectric, and Hydroelectric. Record counts (shown at bar ends) are plotted on a log scale.

Assignment of uncategorized records to more specific use categories significantly refined USWWD’s classification of irrigation, agriculture, and power categories. Unspecified irrigation records decreased by 75.3% (from 2,010,744 to 497,003), while broad agriculture records decreased by 45.0% (from 221,471 to 121,819). Of the 1,613,393 uncategorized irrigation and agriculture records, most were allocated to Irrigation - Crop (1,574,557; 97.6%), followed by Irrigation - Golf Courses (23,021; 1.4%), Livestock (15,784; 1.0%), and Aquaculture (31; <0.1%). In the power category, 11,511 of 25,768 unspecified records (44.7%) were subcategorized, primarily as hydroelectric (8,060; 70.0%) and thermoelectric (2,053; 17.8%), with 1,398 records (12.2%) assigned to other power categories or combinations. Some records remained unspecified after subcategorization: Irrigation – Unspecified (497,003), Agriculture – Unspecified (121,819), and Power - Other (14,257). Figure 4 shows the final distribution of records across all USWWD categories.

Distribution of water use records across categories in the United States Water Withdrawals Database (USWWD). Horizontal bars show record counts (displayed at bar ends) on a logarithmic scale, ordered by sector and frequency. Irrigation - Crop has the highest count (3,861,164), while Sewage Treatment has the lowest (3,458). Power - Other includes multiple power uses, minor categories (e.g., solar), and unspecified power records. Other represents multiple uses or uncategorized records, while Unknown comprises state-designated unknown or missing use types.

Data Records

The USWWD is composed of two .csv files for each state, one containing the main dataset and another the coordinate information. Additionally, metadata associated with USWWD records is included in Table S1 to S5. All the data and metadata files can be found at the HydroShare data repository36 (https://doi.org/10.4211/hs.11c91bde19864106a9e85b39ffcf0ff1) under a CC BY license.

The Data folder in the HydroShare repository36 contains 42 individual state folders, each named using the two-letter abbreviation for the respective state. Within each state folder, there are two files in.csv format: one containing water use data with the suffix “_USWWD_Water_Use_Characteristics” and another containing point of diversion or use data with the suffix “_USWWD_Water_Withdrawal_Use_Locations”. For convenience, the Data folder also includes a compressed file named All_Data.zip that consolidates all state data in one location.

New water withdrawal records are continuously collected by each state. However, USWWD currently represents a static data product that captures all reported records at the time when data was collected from each state, which differs for each state (see Table S1). This version of USWWD described in this work represents a specific snapshot in time and will remain unchanged as the peer-reviewed data product. A significant obstacle in maintaining an up-to-date database is the variability in public data access across states and the lack of automated data collection procedures (e.g., state-provided APIs for programmatic data access). While some states readily release their data, others do not have an established method to do so. Some states require public records law (e.g., Freedom of Information Act, FOIA) requests, a process often mired in bureaucratic delays. Furthermore, the inconsistency in how regularly different states update their databases poses a challenge in keeping USWWD current. Despite these hurdles, the potential benefits of a dynamic, regularly updated database are substantial. Any future versions or updates to this database would constitute separate data products distinct from the static version presented here. Such a database would significantly contribute to ongoing research and societal needs but would likely require the resources of a federal agency, such as USGS, to continually maintain and publish such a comprehensive data product.

Technical Validation

USWWD provides the most comprehensive accounting of US water withdrawal data at the individual user level, offering time series of water withdrawals for 188,857 unique water users. Our study is the first to conduct a nationwide survey, reaching out to all 50 states plus Washington D.C., to assess the extent and availability of historical water use data at this granular level. It is also the first to publicly release a nationwide, standardized data product describing both water withdrawal and places of diversion and/or use at the user level. As such, direct comparison of this dataset with previous studies is challenging, as comparable data either does not exist or has not been made publicly available for detailed analysis. The one exception is the USGS’ five-year data report, though that data is aggregated at the county level and only updated quinquennially. However, USGS maintains extensive water use data within their Site-Specific Water-Use Data System (SSWUDS)37, which contains much of the information comparable to USWWD. However, these site-specific data remain inaccessible to the public. It is important to note that the USWWD does not replace but rather complements USGS’ quinquennial data, as the latter incorporates not only self-reported withdrawals, as is the case with USWWD, but also fills in data gaps through modelled water use estimates. This distinction underscores the unique value and contribution of the USWWD to the research community as it provides detailed withdrawal time series along with their places of diversion and/or use, not available in the USGS’ water use database.

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the collected data, we implemented a validation process that focused on three main areas: flagging records with one or more matches, flagging records with locational mismatches, and flagging records with anomalous volumes. Besides the comprehensive qualitative context and data description provided in Table S1 and throughout this data descriptor, this systematic quantitative technical validation of these specific data characteristics is intended to provide further information for the user about possible data quality issues. Rather than removing questionable records, we opted for a flagging approach to preserve all data provided by state agencies, allowing end users to make informed decisions about whether to include or exclude flagged records in their analyses. The following paragraphs describe each of these procedures in detail, along with their respective results, providing a transparent overview of our data validation procedures and their outcomes.

Beyond removing erroneous duplicates, identical records, we implemented a procedure to flag records with one or more matches based on matching water user name, reported volume, reporting period, and state use category. This identification was performed on the original state dataset, before any data processing was done, to maintain data integrity. The number of columns used for flagging varied by state due to differences in data structure (e.g., monthly volumes in 12 columns versus one column). We deliberately limited the number of matching attributes to maintain a conservative approach and avoid false negatives. This approach prevents misinterpretation of reported volumes, for example, when a user withdraws from multiple PODs during a period and reports cumulative volumes for each POD.

Out of 7,524,266 total records in USWWD, 1,815,748 (24.1%) had zero or null volumes (Fig. 5a). These rows were excluded from flagging records with one or more matches procedure since including them would artificially inflate the number of records with matches, as records with zero or null volumes are more likely to appear identical. Among the remaining 5,708,518 records with at least one non-null, non-zero volume, 913,381 (16.0%) were identified as having one or more matches (Fig. 5b). The percentages of records with one or more matches varied across states, ranging from 45.5% in Vermont to none in Maryland and Louisiana, with an average of 7.8% and a standard deviation of 10.9% across all states.

Results of records with one or more matches flagging procedure across states. Panel a) shows the percentage of records with zero and/or null volumes in all volume columns (grey) versus percentage of records with at least one non-zero and non-null volumes (green) for each state. Panel b) shows the percentage of records with one or more matches (grey) identified among records with at least one non-zero and non-null volume (green indicates records without matches). States are ordered from top to bottom based on decreasing percentage of records with one or more matches in panel b. The flagging procedure identifies records with one or more matches based on records sharing identical information in key attributes but only considers records with valid (non-zero/non-null) volume values to avoid artificial inflation of matching record counts.

To identify locational mismatches, we compared the reported county and the POD and POU coordinates in the state records. This process involved assigning each POD and POU to a county based on the county their state-reported coordinates fell within. We then compared the county of water withdrawal or use reported by the states with the county where the POD or POU coordinates were located. In USWWD, records are flagged if the state-reported county and coordinate-specified county differed. This approach can only verify if the coordinates fall within the correct county, not whether they match the actual location of water diversion or use. An exception was made for users withdrawing from the Great Lakes, where coordinates for points of diversion are often located in the water body itself, away from county boundaries; applying the method described would incorrectly flag such records as mismatches despite their coordinates accurately representing the diversion location. Additionally, this verification method is only appropriate when the county derived from the coordinates can be compared against county records that exist in the state dataset.

Only 7,320 out of 343,086 (2.1%) unique POD coordinates and 1,642 out of 18,294 (9.0%) unique POU coordinates were flagged as locational mismatches (Fig. 6). The states of Hawaii and Indiana showed the highest percentages of flagged POD coordinates with 43.9% (928 out of 2,114) and 21.4% (2,773 out of 12,930), respectively. In contrast, California had the lowest percentage of POD coordinates flagged for locational mismatches, with 0.1% (45 out of 35,011) flagged. For POU coordinates, Indiana again had the highest percentage of flagged coordinates with 22.7% (1,281 out of 5,653), followed by Virginia with 5.0% (304 out of 6,108). New York and Ohio had the lowest percentages of flagged POU coordinates with 1.8% (33 out of 1,870) and 0.7% (24 out of 3,287), respectively. Some states only reported coordinates; therefore, our quality assurance procedure, which requires at least two locational attributes (i.e., coordinates and county) for comparison, could not be used for these states. Several states (Connecticut, Vermont, Utah) didn’t provide the county for PODs or POUs. Pennsylvania’s data provided coordinates only for PODs, while the county information given was only for POU, making comparison between the county and coordinates unsuitable since they referred to different locations, and Texas reported county information for only a few PODs. Coordinates without comparable county data were tagged as Unspecified, meaning our flagging procedure could not determine location match or mismatch.

Locational accuracy assessment of point of diversion (POD) and place of use (POU). Green points indicate matching counties and coordinates, blue points show locational mismatches, and greyslate points represent locations with unavailable county information, where our coordinate flagging procedure could not determine location match or mismatch. Points shown represent only records in the United States Water Withdrawals Database (USWWD) with POD or POU coordinates; many water use records lack coordinate data and are not depicted (no records have coordinate values in grey-shaded states). USWWD contains no data for hatched states. Note: Some PODs/POUs that appear in grey or hatched states belong to neighbouring states and, thus, are flagged.

The reasons for locational inconsistencies vary across states and stem from a combination of legal, administrative, and practical challenges. Some states have more restrictive data sharing laws and practices, limiting their ability to publish exact coordinates and potentially leading to the obfuscation of location data. The resources dedicated to collecting, verifying, and maintaining data can vary significantly between states, likely contributing to the observed differences in data quality and completeness. Furthermore, variations in data reporting requirements and collection methods across states may result in inconsistencies. Human error also plays a role, as data entry inaccuracies can occur either at the state level during record-keeping or by the initial reporter of the data.

Water use volume data included in USWWD are generally self-reported by the water user. A significant majority of states (34 out of 42) reported implementing procedures to ensure the accuracy of reported data for each user at the time of submission. These procedures typically involved comparing a reported volume to a user’s previous reported volumes. When significant discrepancies were observed, further actions, including contacting the reporting party for explanation or clarification, were taken by the states. Additionally, the quality of reported volumes in terms of measurement or estimation types varies across the dataset: 25.4% (1,914,231 out of 7,524,266) of records were measured, usually involving some form of metering device; 30.6% (2,300,256 records) were mixed (some estimated, some measured, with exact methods unclear for each record); 33.9% (2,553,043 records) were estimated; and 9.4% (709,800 records) had unknown measurement or estimation methods. Records with unknown measurement methods primarily represent cases where measurement type information was missing in the original data. Furthermore, 17 states provided measurement method information for individual records as an attribute in their datasets, while the remaining 25 states provided a single measurement classification, through direct correspondence, that applied to their entire dataset. From the latter states, only five mentioned all their records were metered, with the rest mentioning mixed methods. This variability in data collection and reporting methods warranted a comprehensive volume validation process to ensure the reliability and consistency of the USWWD dataset. Figure 7 indicates the distribution of different measurement types by water use categories.

Method of water use measurement or estimation by water use category. Bars show the percentage breakdown of water use records classified as Measured (direct measurement), Mixed (combination of measured/estimated), Estimated (calculated without direct measurement), or Unknown (measurement method undocumented/missing) across different water use sectors.

The volume validation process employs a two-tiered approach to identify anomalous withdrawal volumes. First, the USGS threshold assessment operates at the aggregated county level, comparing each reported annual volume against maximum values derived from USGS county-level water use reports for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015, with separate thresholds for groundwater, surface water, and total use categories. These specific USGS year reports were selected as they coincide with the temporal coverage of the majority of USWWD data. For records with known water sources, the appropriate source-specific threshold is applied, while records with unspecified sources are evaluated against the higher of the groundwater or surface water thresholds, or the total threshold if source-specific values are unavailable. Second, the anomalous volume detection operates at the individual user level, examining each user’s historical patterns by calculating deviations from their median usage using interquartile range statistics. In USWWD, each reported water withdrawal volume was categorized as True (exceeds threshold/anomalous), False (not anomalous, i.e., within normal range), Unspecified (insufficient data for classification), or null (missing values). Zero values were consistently marked as Unspecified since they could represent either no withdrawal or missing data. Additionally, values were marked as Unspecified when users had insufficient historical data (less than 10 non-zero, non-missing values), when their withdrawal patterns showed no variability (zero interquartile range), when there are significant discrepancies (>10% deviation) between annual volumes and the sum of monthly values, or when USGS threshold data is missing or zero for the relevant county-sector combination. Missing (null) values were excluded from the assessment at the second tier of assessment (i.e., at the individual user level). Flagging is applied separately and independently to each of the twelve monthly volume columns and the annual volume column, identifying values that exceed three IQR distances from the median as anomalous.

This approach ensures that only records with sufficient historical context and reliable reference data are definitively flagged, while maintaining conservative classification for cases with limited information. The validation system produces separate flag columns: one for USGS threshold exceedances and thirteen columns for anomalous volume detection (one for each monthly volume and one for annual volume). We reiterate that we do not alter the volume records provided by the state and our flagging approach does not guarantee that a value is erroneous or correct. Instead, our flag highlights volume values that are anomalous based on our quality assurance measures. Our approach identified anomalies while accounting for legitimate variations across space, time, and sectors.

The volume validation process identified 1.3% (733,031 out of 58,439,412 total) of all USWWD reported volumes as anomalous. Flagging of anomalous monthly withdrawal volumes varied slightly seasonally, with June showing the highest flagging at 1.8% (79,585 out of 4,447,622) and February the lowest at 0.9% (40,632 out of 4,405,746), while annual data showed 1.4% (78,474 out of 5,440,563) flagged. When considering only non-zero volumes, flagging percentages remained consistent across months, averaging 3.3% (standard deviation 0.7%). Most volumes tagged as Unspecified were zeros (89.8%–30,696,056 out of 34,191,880), with unspecified tags decreasing during irrigation season (May-September) when fewer zeros appeared in the irrigation category, USWWD’s largest use category. This monthly consistency indicates stable reporting quality with randomly distributed errors. Additionally, only 0.5% (40,587 out of 7,524,266) of annual volume records exceeded USGS threshold values. Figure 8 shows the distribution of anomalous, not anomalous, and unspecified volumes across monthly and annual data.

Monthly and annual distribution of anomalous, not anomalous, and unspecified volume flagging procedure in the United States Water Withdrawal Database (USWWD). The figure shows the percentage of reported water withdrawal volume classified as True (blue, potentially anomalous), False (green, within normal range, not anomalous), and Unspecified(grey, insufficient data for classification). Summer irrigation months (May-September) show higher percentages of both anomalous and not anomalous volumes, corresponding to increased irrigation water use reporting activity.

Overall, results of the volume accuracy assessment across months, year, and states, indicate that the data is largely free of large outliers that may suggest data quality issues, as evidenced by the consistently low percentages of anomalous withdrawal volumes. The similarity in anomalous volume percentages across states and reporting periods suggests a relatively uniform withdrawal volume data quality throughout the USWWD. Figure 9 provides a visualization of the withdrawal volume flagging results across all states, illustrating the distribution of anomalous, not anomalous, and unspecified volumes for each state in the dataset (panel a), as well as the distribution of volumes that exceed, do not exceed, or have unspecified USGS threshold comparisons (panel b). The reported withdrawal volumes in Louisiana and Utah have the highest percentages of anomalous volumes at 2.3% (677 out of 29,783) and 2.2% (19,076 out of 879,177), respectively. Notably, the percentages of anomalous volumes for the rest of the 40 states in USWWD were under 2.0%. All withdrawal volumes in Colorado (4,992) were tagged as Unspecified, primarily due to insufficient user history (less than 10 reported withdrawal volumes per user). Colorado also has the least number of records (i.e., 384), significantly below the USWWD median of 71,699 records per state. Furthermore, the percentages of annual volumes exceeding the USGS maximum values for a county-sector-water source combination over the last four USGS five-year report data is under 5.0%. Most states have none of their volumes flagged as exceeding the USGS maximum values. Colorado has the highest percentage of its volumes flagged (4.9%) as exceeding the USGS maximum values; however, this percentage equals only 19 out of a total of 384 volumes in this state.

Results of flagging procedure for volume data in the United States Water Withdrawal Database (USWWD) by state. Panel (a) shows the percentage of reported withdrawal volumes - including both monthly and annual values - classified as Anomalous (blue), Not Anomalous (green), and Unspecified (grey, insufficient data for classification) in USWWD. Panel (b) shows the percentage of annual withdrawal volumes classified as Exceeds (blue, exceeds USGS maximum value), Does not Exceed (green, under USGS maximum value), and Unspecified (grey, insufficient data for comparison). Zero values were classified as Unspecified. Null values were not considered in the volume flagging procedure. States are arranged in descending order based on the percentage of anomalous volumes from top to bottom in panel (a). The percentage values displayed on each bar segment represent the proportion of volumes in each category relative to the total for that state. Past Florida in panel (a), the percentages of Anomalous volumes are not shown because they are less than one percent.

Next, we compared the non-anomalous and non-unspecified volume values in USWWD that also did not exceed the USGS maximum values with the USGS’ five-year reports for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015. While there is a difference in spatial resolution between the datasets (USWWD at individual user level versus USGS at county level), both datasets maintain annual temporal resolution. We assessed the median annual water withdrawal (Fig. 10a) and compared the average annual withdrawal water volume across different sectors between USWWD and the USGS five-year data products (Fig. 10b).

Comparison of water withdrawal volumes across different water use sectors in the United States Water Withdrawal Dataset (USWWD) and United States Geological Survey (USGS) five-year water use reports. Panel a) shows the median annual water withdrawal volume (in thousand gallons per day) for each sector in the USWWD. Panel b) presents the average total annual water withdrawal (in billion gallons per day) by sector for USWWD (bars with different colors for each sector) compared with USGS five-year reported withdrawal data (red dots) averaged across the years 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015. The USGS values represent county-level aggregated data while USWWD values represent user-level self-reported data. However, here both data are summed across the 42 states where they both report water withdrawals and then averaged across the reporting years. Note that the anomalous and unspecified volume values in USWWD as well as volume from records with one or more matching records were removed before comparison with the USGS values.

We chose the median values for the USWWD (Fig. 10a) due to the right-skewed distribution of volume values across sectors, which would otherwise bias the mean. The power category, which includes individual sectors of Power-Thermoelectric, Power-Hydroelectric, and Power-Other, demonstrates the highest median withdrawals, with hydroelectric power showing the highest median withdrawal (191,864.0 thousand gallons per day, TGD) across both the power category, as well as all USWWD sectors. This exceptionally high value for hydroelectric power is primarily attributed to the non-consumptive nature of water use in this sector, where most of the withdrawn water is returned to its source after power generation. In contrast, the domestic sector shows the lowest median withdrawal (1.1 TGD), which aligns with expected individual household-scale usage patterns.

The average annual withdrawal volumes summed across all water users within a sector (Fig. 10b) strongly correlates with the median annual volume values of individual users (Fig. 10a) across sectors (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.85). This result shows that differences in water withdrawals between sectors is primarily driven by water use intensity (i.e., water withdrawals per user), not by differences in the number of records. The correlation between the average total annual water withdrawal values between USWWD (bars, Fig. 10b) and USGS water withdrawal data (red dots, Fig. 10b) for the common sectors is also very high (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.97) indicating very close alignment of the USWWD and the USGS values. As anticipated, the USGS average annual withdrawals exceed their USWWD counterparts across all common sectors, which can be attributed to USWWD’s exclusive representation of state-reported data, while USGS incorporates state-reported data, as well as supplemental data and modelling results. The most substantial differences between USGS and USWWD data are observed in the thermoelectric power sector (difference of 120.9 billion gallons per day, BGD), irrigation (58.9 BGD), and public supply (22.5 BGD). However, these sectors also represent the largest water withdrawal sectors reported by USGS. In terms of percentages, the USWWD values represent approximately 24.0%, 33.4%, and 42.1% of the USGS values for these sectors, respectively. Across all common sectors, USWWD values average 24.7% of USGS reported values, with a standard deviation of 14.8%, ranging from a minimum of 5.8% for livestock to a maximum of 50.2% for industrial.

Building on the previous national-level analysis, we extended our comparison to examine state-level patterns between USWWD and USGS data to better understand regional variations and possible data coverage limitations across different states. This state-level analysis can provide insights for potential users regarding the relative representativeness of USWWD data, by comparison with the USGS data, which also includes modelled water withdrawal estimates used to fill state data gaps, across different geographic areas and sectors. We compared average annual withdrawal volumes from USWWD (using only non-anomalous, non-unspecified values that did not exceed USGS thresholds) with corresponding USGS state-level aggregated data for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015 across aggregated sectors and each individual common sector (Fig. 11). Aggregated across all sectors, the USGS value reported for each state is on average (median) 3.9 times larger than USWWD data (panel a). However, there is a large variance (standard deviation 77.2 times) in reported withdrawal volumes, which is why we compared values on a categorical rather than continuous scale. In general, USWWD data appears more comparable to USGS data in the eastern/northeastern part of the country, as indicated by more states where USGS data is only one to two times larger compared to states with four times or more larger USGS water withdrawal values in western states. However, there are a few sector-state combinations where USWWD values are larger than corresponding USGS values, especially for industrial (panel d), public supply (panel c), and domestic sectors in California (panel e). In these cases, the differences between USGS and USWWD are not very large, unlike when USGS values exceed USWWD values, especially in the western part of the country. It is important to note that unpaired data, USGS data for a year-sector-state combination where equivalent USWWD data is missing, does not mean USWWD lacks any data for that sector-state combination but rather indicates no data availability during the specific four years (2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015) for which USGS data exist.

State-level comparison of water withdrawal volumes, in billion gallons per day, between the United States Water Withdrawal Dataset (USWWD) and USGS five-year water use reports across common water use sectors and in total. Panels (a-i) represent: (a) total water withdrawals aggregated across all sectors, (b) irrigation, (c) public supply, (d) industrial, (e) domestic, (f) livestock, (g) aquaculture, (h) mining, and (i) power - thermoelectric. Colors indicate the magnitude of difference between datasets: green shades show states where USGS reports 1-2 times (light green), 2–4 times (medium green), or more than 4 times (dark green) larger withdrawal volumes than USWWD; blue shades show states where USWWD reports 1-2 times (light blue), 2–4 times (medium blue), or more than 4 times (dark blue) larger volumes than USGS. Gray indicates unpaired data (missing data in USWWD for the particular year-sector-state combination), and hatched areas represent states with no data in USWWD. Data represent average annual withdrawals across 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015, with USGS county-level data aggregated to the state level for comparison with USWWD state-level self-reported data.

The state-level analysis reveals varying degrees of coverage between USWWD and USGS data across different states and sectors. The ratio of USGS to USWWD values shows considerable variation by sector, with median ratios ranging from 1.28 times larger for industrial uses to 59.6 times larger for domestic uses, which is unsurprising since most states require reporting of water diversions by large industrial water users but not domestic users. Geographic patterns indicate that eastern states generally demonstrate closer alignment between USGS and USWWD values compared to western states, likely reflecting differences in state reporting requirements and larger unrecorded irrigation water uses in the western US, which required USGS to use models to fill in data gaps. The lack of full data coverage across states due to the limitations of state data collection protocols or privacy restrictions limiting what can be reported in USWWD explain much of the differences between USGS and USWWD data. While USWWD only provides water withdrawal values reported by states (which, in turn, are often reported to the states by the water users), USGS supplements state-reported values with their own modelled estimates to fill in spatial, temporal, and sectoral data gaps. For example, Illinois only shared their public supply data with us, while other sectoral data were withheld due to agency-specific policies regarding data sharing. In addition, we narrowly focus on user-level water withdrawal records, which further limits data recorded in USWWD. For example, in USWWD we have 384 records for Colorado, while Colorado’s Decision Support Systems portal contains information for tens of thousands of diversion structures. However, we did not collect that data from Colorado since it was at the point of diversion/headgate level – potentially providing water to several water users – rather than the user level, which is the focus of our database.

We emphasize that comparisons between USWWD and USGS values are conducted for only four years (2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015) for which USGS data exists for all sectors, while USWWD represents multi-year, sub-annual data with most records spanning before and after the USGS reporting years. Importantly, USWWD should not be treated as a comprehensive census of all water uses in the US. Instead, it should be viewed as a large non-representative survey of water users, with spatial, temporal, and sectoral variances in coverage. As such, users of USWWD should evaluate the relative coverage and representativeness of USWWD data for their specific geographic area and sector of interest, recognizing that coverage varies across jurisdictions, time, and sector.

The comparison between USWWD and USGS water withdrawal data, while subject to limitations in temporal and spatial resolution and completeness, serves as a crucial reliability point that demonstrates reasonable comparison of self-reported water use data to an authoritative data source. While our approach creates a relatively consistent method that can be applied across most sectors, users of USWWD could conduct additional comparisons that are unique to each sector. For instance, public supply withdrawals could be compared against EPA data38 on population served and treatment capacity for specific utilities, providing additional accuracy metrics for reported volumes. Similarly, thermoelectric sector withdrawals could be cross-referenced with facility-level water withdrawal data reported by the Energy Information Administration (EIA)39. Developing unique validation measures for each sector would permit a more granular comparisons at both temporal (e.g., monthly) and spatial (e.g., individual user) scales using other publicly-available datasets; however, this could only be done for select sectors, as most sectors have little data to validate against, even at a crude level. Still, such detailed, sector-specific validation approaches would further enhance our understanding of self-reported water use data quality and help establish more refined validation criteria.

Data availability

The data included in USWWD are publicly available at the HydroShare data repository36.

Code availability

All codes for data standardization and technical validation are available at the HydroShare data repository36.

References

Das, P., Patskoski, J. & Sankarasubramanian, A. Modeling the irrigation withdrawals over the coterminous US using a hierarchical modeling approach. Water Resour. Res. 54, 3769–3787 (2018).

Marston, L. T. et al. Water‐Use Data in the United States: Challenges and Future Directions. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 58, 485–495 (2022).

Overpeck, J. T. & Udall, B. Climate change and the aridification of North America. Proc. 117, 11856–11858 (Natl. Acad. Sci., 2020).

Marston, L., Ao, Y., Konar, M., Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. High-Resolution Water Footprints of Production of the United States. Water Resour. Res. 54, 2288–2316 (2018).

Rao, P. et al. Manufacturing Water Use. ACEEE Summer Study Energy Effic. Ind. 104–115 (2017).

Fishman, C. Water is broken. Data can fix it. New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/14/opinion/sunday/fixing-our-broken-water-systems.html (2016).

Becker, R. A. Water Use and Conservation in Manufacturing: Evidence from U.S. Microdata. Water Resour. Manag. 30, 4185–4200 (2016).

Mccall, J. et al. U.S. Manufacturing Water Use Data and Estimates: Current State, Limitations, and Future Needs for Supporting Manufacturing Research and Development. ACS ESampT Water 1, 2186–2196 (2021).

Josset, L. et al. The U.S. Water Data Gap—A Survey of State-Level Water Data Platforms to Inform the Development of a National Water Portal. Earths Future 7, 433–449 (2019).

Basker, E., Becker, R. A., Foster, L., White, T. K. & Zawacki, A. Addressing Data Gaps: Four New Lines of Inquiry in the 2017 Economic Census. 19–28 (Center for Economic Studies, U.S. Census Bureau, 2019).

Armstrong, K. O., Garcia Gonzalez, S. & Nimbalkar, S. U. Opportunities for Using the Industrial Assessment Center Database for Industrial Water Use Analysis. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1767861 (Oak Ridge National Lab. (ORNL) 2020).

Dupont, D. P. & Renzetti, S. The Role of Water in Manufacturing. Environ. Resour. Econ. 18, 411–432 (2001).

Marston, L. T. et al. Reducing water scarcity by improving water productivity in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094033 (2020).

Lopez, S. F. et al. Database of surface water diversion sites and daily withdrawals for the Upper Colorado River Basin, 1980–2022. Sci. Data 11, 1266 (2024).

Chini, C. M. & Stillwell, A. S. Where Are All the Data? The Case for a Comprehensive Water and Wastewater Utility Database. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 143, 01816005 (2017).

Sugg, Z. Social barriers to open (water) data. WIREs Water 9, e1564 (2022).

U.S. Geological Survey. Water Use. https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/water-use (2024).

U.S. Geological Survey. National Water Census. https://www.usgs.gov/programs/water-availability-and-use-science-program/national-water-census (2025).

Hutson, S. et al. Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2000. (U.S. Geological Survey, 2004).

Kenny, J. F. et al. Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2005. http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/cir1344 (U.S. Geological Survey, 2009).

Maupin, M. A. et al. Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2010. http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/cir1405 (U.S. Geological Survey, 2014).

Dieter, C. A. et al. Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2015. http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/cir1441 (U.S. Geological Survey, 2018).

Luukkonen, C. L. et al. Public supply water use reanalysis for the 2000–2020 period by HUC12, month, and year for the conterminous United States (ver. 2.0, August 2024). https://doi.org/10.5066/P9FUL880 (U.S. Geological Survey, 2024).

Martin, D. et al. Irrigation water use reanalysis for the 2000–20 period by HUC12, month, and year for the conterminous United States (ver. 2.0, September 2024). https://doi.org/10.5066/P9YWR0OJ (U.S. Geological Survey, 2024).

Galanter, A. E. et al. Thermoelectric-power water use reanalysis for the 2008-2020 period by power plant, month, and year for the conterminous United States. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9ZE2FVM (U.S. Geological Survey, 2023).

Wilkinson, M. D. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018 (2016).

Siddik, M. A. B., Dickson, K. E., Rising, J., Ruddell, B. L. & Marston, L. T. Interbasin water transfers in the United States and Canada. Sci. Data 10, 27 (2023).

Lin, C.-Y., Miller, A., Waqar, M. & Marston, L. T. A database of groundwater wells in the United States. Sci. Data 11, 335 (2024).

Zipper, S. et al. Estimating irrigation water use from remotely sensed evapotranspiration data: Accuracy and uncertainties at field, water right, and regional scales. Agric. Water Manag. 303, 109036 (2024).

Lamsal, G. & Marston, L. T. Monthly Crop Water Consumption of Irrigated Crops in the United States From 1981 to 2019. Water Resour. Res. 61, e2024WR038334 (2025).

Watershed Boundary Dataset: HUC 12s (Mature Support). https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=0f76175ca3a4424a9ce2328b1daf931a (2024).

USA Counties Generalized Boundaries. https://virginiatech.maps.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=3c164274a80748dda926a046525da610 (2024).

Regrid. Regrid 2025 U.S. Nationwide Premium Schema Parcel Dataset. Regrid. Available at: https://www.regrid.com (Accessed: August 15, 2024) (2025).

OpenStreetMap. https://www.openstreetmap.org/ (2024).

Power Plants. https://atlas.eia.gov/datasets/eia::power-plants/about (2024).

Naseri, M. Y., L. Marston The United States Water Withdrawals Database (USWWD), HydroShare, https://doi.org/10.4211/hs.11c91bde19864106a9e85b39ffcf0ff1 (2025).

U.S. Geological Survey. Water-use related data in the USGS Site-Specific Water-Use Data System. https://www.usgs.gov/media/files/water-use-related-data-usgs-site-specific-water-use-data-system (2018).

US EPA. Water Data and Tools. https://www.epa.gov/waterdata (2025).

EIA. Thermoelectric cooling water data. https://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/water/ (2025).

Arizona Department of Water Resources. https://www.azwater.gov/ (2024).

Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. https://dnrec.delaware.gov/ (2024).

Southwest Florida Water Management District. https://www.swfwmd.state.fl.us/ (2024).

Indiana Department of Natural Resources. https://www.in.gov/dnr/ (2024).

Kansas Department of Agriculture. https://www.agriculture.ks.gov/ (2024).

Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet. https://eec.ky.gov/Pages/index.aspx (2024).

Maryland Department of the Environment. https://mde.maryland.gov/Pages/default.aspx (2024).

Missouri Department of Natural Resources. https://dnr.mo.gov/ (2024).

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. https://dec.ny.gov/ (2024).

Washington State Department of Ecology. https://ecology.wa.gov/ (2024).

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/ (2024).

Alaska Department of Natural Resources. https://dnr.alaska.gov/mlw/water/hydro/ (2024).

Arkansas Department of Agriculture. https://www.agriculture.arkansas.gov/natural-resources/ (2024).

California State Water Resources Control Board. https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/ (2024).

Colorado Department of Natural Resources. https://cwcb.colorado.gov/ (2024).

CT Department of Energy & Environmental Protection. https://portal.ct.gov/deep (2024).

Northwest Florida Water Management District. https://nwfwater.com/ (2024).

Suwannee River Water Management District. https://www.mysuwanneeriver.com/ (2024).

St. Johns River Water Management District. https://www.sjrwmd.com/ (2024).

GA Department Of Natural Resources. https://gadnr.org/ (2024).

HI Department of Land and Natural Resources. https://dlnr.hawaii.gov (2024).

Prairie Research Institute. https://prairie.illinois.edu/ (2024).

Iowa Department of Natural Resources. https://www.iowadnr.gov/ (2024).

Capital Area Ground Water Conservation District. https://www.capitalareagroundwater.com (2024).

Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection. https://www.mass.gov/orgs/massachusetts-department-of-environmental-protection (2024).

Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes & Energy (EGLE). https://www.michigan.gov/egle (2024).

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/ (2024).

Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality. https://www.mdeq.ms.gov/ (2024).

NH Department of Environmental Services. https://www.des.nh.gov/ (2024).

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. https://dep.nj.gov/ (2024).

North Carolina Dept. of Environmental Quality. https://www.deq.nc.gov/ (2024).

North Dakota Department of Water Resources. https://www.dwr.nd.gov/thedwr/ (2024).

Ohio Department of Natural Resources. https://ohiodnr.gov/home (2024).

Oklahoma Water Resources Board. https://oklahoma.gov/owrb.html (2024).

Oregon Water Resources Department. https://www.oregon.gov/owrd/pages/index.aspx (2024).

Pennsylvania Department Of Environmental Protection. https://www.dep.pa.gov/Pages/default.aspx (2024).

South Carolina Department Of Health & Environmental Control. https://scdhec.gov/ (2024).

South Dakota Department of Agriculture & Natural Resources. https://danr.sd.gov/default.aspx (2024).

Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. https://www.tn.gov/environment.html (2024).

Texas Water Development Board. https://www.twdb.texas.gov/ (2024).

Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. https://www.tceq.texas.gov (2024).

Utah Division of Water Rights. https://www.waterrights.utah.gov/ (2024).

Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation. https://dec.vermont.gov/ (2024).

Virginia DEQ. https://www.deq.virginia.gov/ (2024).

WV Department of Environmental Protection. https://dep.wv.gov/Pages/default.aspx (2024).

Wyoming State Engineer’s Office. https://seo.wyo.gov/home (2024).

Acknowledgements

L.T.M. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (CBET-2144169) and the United States Geological Survey (Grant No. G23AC00071-00). This work was also supported in part by the “Reanalyzing and predicting U.S. water use by economic history and forecast data; an experiment in short-range national hydroeconomic data synthesis” Working Group supported by the John Wesley Powell Center for Analysis and Synthesis, funded by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Grant/Cooperative Agreement No. G20AP00002. The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. We are deeply grateful to the numerous state agency employees – most of whom are named in the metadata – who provided and explained their water use data to us. Their assistance was indispensable to this work. We also extend our appreciation to Cheryl A. Dieter and her team at USGS for their valuable review of USWWD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.T.M. conceived the study and secured financial support to carry out the research. L.T.M. and M.Y.N. designed the study, including the data standard. M.Y.N. collected the data, standardized and validated the data. Both authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript, with M.Y.N. writing the initial draft and L.T.M. providing edits and revisions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naseri, M.Y., Marston, L.T. United States Water Withdrawals Database. Sci Data 12, 2022 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06300-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06300-1