Abstract

Hypsibarbus vernayi (2n = 50), a medium-sized barb distributed in the Mekong River basin, is widely consumed in its native range and holds significant potential for commercial aquaculture development. To date, there is no high-quality genome available for this species. In this study, we generated a haplotype-resolved and near-T2T assembly of H. vernayi utilizing PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore and Hi-C technologies. The assembled genome sizes for two haplotypes are 709 Mb and 707 Mb with scaffold N50 of 27.8 Mb and 26.8 Mb, respectively. A 262-bp satellite DNA sequence was identified as the centromeric repeats that appeared on almost all chromosomes. The diploid genome contains only eight gaps: one and seven in the two haploid genomes, respectively. Furthermore, 31 out of 50 chromosomes have telomeres assembled at both ends. This high-quality reference genome is expected to facilitate the breeding efforts for this species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

With the advancement of sequencing technologies, the long-reads sequencing and improved assembly algorithms now enable the generation of telomere-to-telomere (T2T) and haplotype-resolved genome1. Recently, the haplotype-resolved T2T genomes of human was completed, providing an alternative reference genome for studying human genetics of East Asian population2. T2T genomes have been achieved extensively in plants, significantly accelerating breeding efforts3. High-quality genome assemblies allow detailed investigation of the complex region in the genome such as centromere, tandem duplications, and segmental duplication1,4,5,6. However, haplotype-resolved T2T genomes remain scarce in non-primate vertebrates, limiting our understanding of the evolution of complex region in these groups5.

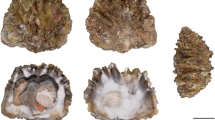

With an increasing number of reports on distant hybridization in fish7, the discovery and utilization of wild germplasm resources could significantly accelerate fish breeding effects8,9,10. Hypsibarbus vernayi (Cypriniforms: Cyprinidae) is a medium-sized barb distributed throughout the Mekong River basin in Southeast Asia and Yunnan, China. As a commonly consumed fish in the region, it holds potential value for aquaculture development. To date, A high-quality genome assembly is still lacking for this species. A well-assembled genome has potentials in accelerating genetic breeding and aquaculture development.

In this study, we assembled a haplotype-resolved and near-T2T genome of H. vernayi using PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore, and Hi-C data. The high-quality genome provides a valuable genetic resource for the aquaculture and breeding of cyprinid fishes.

Methods

Material sampling, DNA extraction and sequencing

A male H. vernayi was sampled from Yunnan Agriculture University. Five tissues were collected for RNA sequencing, including brain, liver, kidney, heart, and spleen. The sampling and experimental protocol of this study complied with animal welfare laws and guidelines and was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of Yunnan Agricultural University, Kunming, China (Approval No. APYNAU202202018). Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from muscle using standard phenol-chloroform extraction. For Oxford Nanopore library construction, SQK-LSK110 kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK) was used following the manufacturer’s instructions. Then the library was sequenced on the PromethION sequencer (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK). For Pacbio HIFI sequencing, the quality and length of gDNA was assessed using Qubit 1X dsDNA HS assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and gDNA 165 kb kit on Femto Pulse system (Agilent Technologies, USA). The SMRTbell library was constructed using SMRTbell® prep kit 3.0 (Pacific Biosciences, USA) according to the manufacturer’s standard protocol. DNA fragments shorter than 5 Kb were discard by magnetic beads using AMPure PB bead size selection kit (Pacific Biosciences, USA) following manufacturers’ instructions. Then the library was sequenced on Pacbio Revio system (Pacific Biosciences, USA). The Hi-C library was constructed following the protocol described by Lieberman-Aiden et al.11. The liver tissues were processed by cell cross-linking, DNA digestion and fragmentation (DpnII), biotin labelling, proximal chromatin DNA ligation, enrichment of biotin-labelled fragments, and purification. The concentration and insert size were evaluated using Qubit 3.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, USA). The library was sequenced on the NovaSeq X Plus platform with the PE 150 bp mode. For RNA sequencing, total RNA was extracted with RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (TIANGEN, China). mRNA was purified using oligo(dT)-attached mRNA capture beads. Library construction and sequencing were performed at the Wuhan Benagen Technology Company Limited. A total of 110.9 Gb (~78.3X) PacBio HiFi reads, 38.2 Gb (~27.0X) Oxford Nanopore reads and 250.6 Gb Hi-C reads were generated, enabling us to assemble a phased diploid genome.

Genome survey and assembly

We conducted a genome survey using long-read data based on the k-mer method. Kmc v3.2.412 was applied to count k-mer frequency with k set as 19. We used GenomeScope213 to estimate the genome size and the percentage of heterozygosity. The estimated genome size based on the k-mer method was 692,991,697 bp with a heterozygosity of 0.593% (Fig. 1b).

For genome assembly, we applied the Hi-C model of hifiasm v0.19.914 using HiFi and Oxford Nanopore reads to generate contigs with default parameters. Then, Juicer pipeline v1.615 was used to map the Hi-C reads against the contigs. 3D-DNA v20100816 was used to generate the.hic file which was visualized and manually adjusted using the software Juicebox Assembly Tools15. The final genome was generated based on the manually corrected assembly. For the alternative haplotype, we used Ragtag v2.1.017 to arrange the contigs based on the assembly of the first haplotype. Then, the juicer pipeline15 and 3D-DNA16 were applied in the same manner as in the previous steps.

De novo genome assembly generated two sets of contigs with genome sizes of 709,573,396 bp and 707,790,980 bp. Based on Hi-C data, 705,107,344 bp and 705,617,558 bp contig sequences were respectively anchored to 25 chromosomes, accounting for 99.37% and 99.69% of the total assembled size of each haplotype (Fig. 1d,e), consistent with the number of most Cypriniformes fishes reported by karyotype studies18. The BUSCO completeness assessment suggested that the completeness of each haplotype genome was 99.0% and 99.1% (Fig. 1c). We also aligned the genome with Onychostoma macrolepis19 using minimap220. The dotplot between two genomes showed a one-to-one synteny among chromosomes (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Genome annotation

For repetitive elements annotation, we used RepeatModeler v2.0.521 for de novo prediction of repetitive sequences. Additionally, we also generated a satellite DNA library using SRF22. The two libraries were combined as input for RepeatMasker v4.1.2-p123 to produce a soft-masked genome which was then used for gene model annotation. Repetitive element annotation revealed comparable contents between the two haplotypes, with 289,423,506 bp (40.79% of the genome) and 284,959,886 bp (40.26%) annotated in the first and second haploid genomes. The identified transposon elements include long interspersed nuclear elements (LINE), short interspersed nuclear elements (SINE), long terminal repeats (LTR) and DNA transposons. DNA transposons are the major component of repetitive elements, accounting for approximately 35% of a haploid genome (Table 1).

We employed the BRAKER324 pipeline to predict gene models incorporating RNA-seq data and the protein sequences of Onychostoma macrolepis. For the other haplotype, lifton25 was used to lift over the homologous gene models from the annotated haplotype. A total of 24,172 protein-coding genes were annotated in the first haploid genome. The second haploid genome was annotated using a homology-based gene model that yielded 24,919 protein-coding genes. The annotated protein-coding gene number was comparable to that of O. macrolepis (24,77026), a closely related cyprinid fish in the subfamily Barbinae (sensu27).

Centromere and telomere identification

We used PyTandemFinder28 to search for the tandem repeat sequences with the highest abundance. The candidate sequences were masked in the genome using RepeatMasker23. Additionally, we validated the identified potential centromeric region by calculating the number of genes, transposon elements, and methylation level at 10 kb windows. To calculated the haploid methylation level, Nanopolish29 was used for methylation calling. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were called for each haplotype, and subsequently used to phase Oxford Nanopore reads into each haplotype. Then, the levels of 5-methylcytosine bases in a CpG context were detected for each haplotypes using the script calculate_methylation_frequency.py provided by Nanopolish. Repeat sequences were visualized using StainedGlass30 to further identify the centromere region. Telomeric repeats were detected using quarTeT31 by searching for the “AACCCT” repeats across the genome. The range of genes, transposon elements, and methylation level were normalized to 0~1.

As a result, a 262 bp (CEN262) sequence was selected as the putative centromeric repeat. The distribution pattern of CEN262 showed a single location on most chromosomes, except the Chr01 and Chr20. The occupation of CEN262 was consistent with regions showing reduced densities of transposable elements, genes, and DNA methylation, characteristics typically associated with centromeric regions (Fig. 2b). For the two chromosomes lacking the CEN262 signal, we examined the tandem repeat annotation to examine whether the centromere had been assembled. We did not detect an obvious repeat in Chr12, but a repeat-rich region was observed in Chr22. This suggests that the centromere of Chr12 may not have been assembled while Chr22 may use another centromeric repeat. Subsequently, we searched for the most abundant tandem repeat in Chr22 and masked the genome following the same steps. A different 262 bp repeat variant (CEN262_ALT) was identified. Based on the centromere position, 13 out of 25 chromosomes in H. vernayi were identified as acrocentric, and the remaining 11 chromosomes were submetacentric.

(a) The distribution of centromeres, telomeres, gap, TE density, and methylation level (blue line) in the first haplotype genome. TE and methylation density are visualized in 10 Kb widows. This haploid genome contains only one gap while the other haploid genome contains 7 gaps (see supplementary fig. 1) (b) Visualization of centromere region of Chr25 suggesting the distribution of CEN262, gene density, 5mC methylation level, and TE density in 10 Kb windows, where ranges are normalized to 0~1. The triangle heatmaps represent pairwise sequence identity between 0.87 Mb sequences.

A total of 41 telomeres were identified in the first haplotype and 43 in the second. In the first haplotype, 12 chromosomes have telomeres assembled at both ends, while the remaining chromosomes have telomeres at a single end (Fig. 2a). In the second haplotype, 19 chromosomes have telomeres at both ends, while 5 have telomeres assembled only at one end (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Structure variation between haplotypes

We used SyRI v1.7.032 to detect structural variations between two haploid genomes. The nucmer from MUMmer v4.0.033 tool was applied for pairwise alignment between two haplotypes. One-to-one alignments with a minimum alignment length of 300 bp were retained for further analysis. Then, SyRI32 was applied to identify the structural variations. The results were visualized using plotsr v1.1.534. Approximately 660 Mb of syntenic regions were identified between the two haplotypes, representing 93% of the genome, indicating a high level of similarity (Fig. 3). The inversion region accounted for 0.069% of the genome (~0.4 Mb), and the translocation region occupied 1% (~7.5 Mb). We also observed a few unaligned regions whose locations corresponded well with centromeric regions.

Data Records

The raw sequencing data have been deposited on NCBI database with BioProject accession PRJNA1280703. The Pacbio HIFI, ONT, and Hi-C data can be found with the accession number SRP59633835. The genome assemblies were deposited to European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) with accession number GCA_977016905.236. The annotation files have been deposited in Figshare37.

Technical Validation

We evaluated the quality and completeness of genome assemblies by BUSCO analysis. The BUSCO completeness assessment of genomes suggested that the completeness of the two haplotype genomes were 99.0% and 99.1%, respectively (Fig. 1c). The contig-level genomes by hifiasm v0.19.914 contain only 52 and 50 contigs, respectively. Only 8 gaps were contained in the final diploid genomes where 1 gap was in the first haplotype and 7 in the second haplotype. We also assessed the quality of assembled haplotypes using Merqury38. The quality value (QV) for each haplotype was 64.4 and 66.3, respectively, indicating that the accuracy was over 99.99%. The completeness results suggested that about 90% completeness for each haplotype (90.659 for hap1 and 90.624 for hap2), while the total completeness for the diploid genome was 99.89%. These results suggested that the genome was assembled with high quality.

Code availability

No custom code was used for the analyses and the corresponding software have been described in Methods.

References

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Genome assembly in the telomere-to-telomere era. Nat Rev Genet 25, 658–670 (2024).

Yang, C. et al. The complete and fully-phased diploid genome of a male Han Chinese. Cell Res 33, 745–761 (2023).

Garg, V. et al. Unlocking plant genetics with telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies. Nat Genet 56, 1788–1799 (2024).

Huang, Z. et al. Evolutionary analysis of a complete chicken genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 120, e2216641120 (2023).

Bredemeyer, K. R. et al. Single-haplotype comparative genomics provides insights into lineage-specific structural variation during cat evolution. Nat Genet 55, 1953–1963 (2023).

Li, B.-P. et al. Transposable elements shape the landscape of heterozygous structural variation in a bird genome. Zoological Research 46, 75–86 (2025).

Wang, S. et al. Establishment and application of distant hybridization technology in fish. Sci. China Life Sci. 62, 22–45 (2019).

Han, X. et al. The telomere-to-telomere genome assembly and annotation of the rock carp (Procypris rabaudi). Sci Data 12, 781 (2025).

Luo, K. et al. Rapid genomic DNA variation in newly hybridized carp lineages derived from Cyprinus carpio (♀) × Megalobrama amblycephala (♂). BMC Genetics 20, 87 (2019).

Zhou, C. et al. Chromosome‐level genome assembly and population genomic analysis provide insights into the genetic diversity and adaption of Schizopygopsis younghusbandi on the Tibetan Plateau. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1749-4877.12910.

Lieberman-Aiden, E. et al. Comprehensive Mapping of Long-Range Interactions Reveals Folding Principles of the Human Genome. Science 326, 289–293 (2009).

Kokot, M., Długosz, M. & Deorowicz, S. KMC 3: counting and manipulating k -mer statistics. Bioinformatics 33, 2759–2761 (2017).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun 11, 1432 (2020).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. cels 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Alonge, M. et al. Automated assembly scaffolding using RagTag elevates a new tomato system for high-throughput genome editing. Genome Biol 23, 258 (2022).

Khensuwan, S. et al. A comparative cytogenetic study of Hypsibarbus malcolmi and H. wetmorei (Cyprinidae, Poropuntiini). Comparative Cytogenetics 17, 181–194 (2023).

Sun, L. et al. Genbank. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_012432095.1 (2020).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Chu, J., Cheng, H. & Li, H. De novo reconstruction of satellite repeat units from sequence data. Genome Res. 33, 1994–2001 (2023).

RepeatMasker Home Page. https://www.repeatmasker.org/.

Gabriel, L. et al. BRAKER3: Fully automated genome annotation using RNA-seq and protein evidence with GeneMark-ETP, AUGUSTUS, and TSEBRA. Genome Res 34, 769–777 (2024).

Chao, K.-H. et al. Combining DNA and protein alignments to improve genome annotation with LiftOn. Genome Res 35, 311–325 (2025).

Sun, L. et al. Chromosome‐level genome assembly of a cyprinid fish Onychostoma macrolepis by integration of nanopore sequencing, Bionano and Hi‐C technology. Molecular Ecology Resources 20, 1361–1371 (2020).

Chen, X. L., Yue, P. Q. & Lin, R. D. Major groups within the family Cyprinidae and their phylogenetic relationships. Acta Zootaxonomica Sinice (1984).

Kirov, I., Gilyok, M., Knyazev, A. & Fesenko, I. Pilot satellitome analysis of the model plant, Physcomitrella patens, revealed a transcribed and high-copy IGS related tandem repeat. CCG 12, 493–513 (2018).

Simpson, J. T. et al. Detecting DNA cytosine methylation using nanopore sequencing. Nat Methods 14, 407–410 (2017).

Vollger, M. R., Kerpedjiev, P., Phillippy, A. M. & Eichler, E. E. StainedGlass: interactive visualization of massive tandem repeat structures with identity heatmaps. Bioinformatics 38, 2049–2051 (2022).

Lin, Y. et al. quarTeT: a telomere-to-telomere toolkit for gap-free genome assembly and centromeric repeat identification. Horticulture Research 10, uhad127 (2023).

Goel, M., Sun, H., Jiao, W.-B. & Schneeberger, K. SyRI: finding genomic rearrangements and local sequence differences from whole-genome assemblies. Genome Biol 20, 277 (2019).

Marçais, G. et al. MUMmer4: A fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLOS Computational Biology 14, e1005944 (2018).

Goel, M. & Schneeberger, K. plotsr: visualizing structural similarities and rearrangements between multiple genomes. Bioinformatics 38, 2922–2926 (2022).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP596338.

Wang, Z., Gao, Y., Xie, C., Xu, L. & Kong, L. European Nucleotide Archive https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/GCA_977016905.2 (2025).

Wang, Z., Gao, Y., Xie, C., Xu, L. & Kong, L. Hypsibarbus vernayi genome annotations. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29410904.v1 (2025).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol 21, 245 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by Yunnan Province Major Special Plan (202202AE090018) to LK, the Chongqing Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (CSTB2024NSCQ-JQX0021) to LX, and Young Talent Project of the “Xing Dian Talent Support Program” of Yunnan Province in 2022 to YG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.K., Y.G. and L.X conceived and supervised the project. Z.W. and C.X. performed the analyses. Y.G. conducted the histological observation. Z.W. and C.X. wrote the draft and revised by L.K., Y.G. and L.X. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Gao, Y., Xie, C. et al. The haplotype-resolved and near telomere-to-telomere genome assembly for Hypsebarbus vernayi. Sci Data 13, 24 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06338-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06338-1