Abstract

Scientific data has become a cornerstone of contemporary biomedical research, yet the academic recognition of data contributions remains underexplored. In this study, we leveraged the open-access biomedical literature in the PMC (PubMed Central) to identify GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) datasets and extract their associated original papers. By examining the authorship relationships between dataset contributors and paper authors, we quantitatively assessed the academic recognition of scientific data. Our findings reveal that approximately 80% of dataset contributors play pivotal roles in their respective original papers, either as first or corresponding authors, with this proportion continuing to rise. This trend highlights the growing importance of data collection, processing, and analysis in the research process, along with its increasing recognition by the scientific community. Furthermore, we observed that high-impact journals invest more resources in enhancing data quality, thereby improving research credibility, academic influence, and overall research outcomes. These results underscore the gradual shift toward recognizing the value of scientific data work, which is critical for advancing research quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The development of data collection devices and technologies has provided the foundational resources for humans to quantitatively comprehend the world1,2. By scientifically constructing associations between datasets, vast amounts of data can be fully utilized and transformed into important productive resources, a phenomenon which has attracted global attention3,4. Nowadays, data serves as a crucial resource across various fields, bringing tangible benefits5. Notable uses include intelligent diagnosis in medicine, emotion recognition in psychology, and user profiling and product recommendations in intelligent business applications6. As Hirsch7 noted, big data is “rapidly becoming an important corporate asset, a key economic input, and the foundation of new business models.” Research data, as a critical component of the broader data landscape, plays an irreplaceable role in scientific research and technological development8. The 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to British AI scientist Demis Hassabis and American scientist John M. Jumper in recognition of their outstanding contributions to the field of biological macromolecule structure prediction through the development of AlphaFold9. The success of large models trained on vast research datasets highlights that research data not only provides a foundation for theoretical model validation and experimental analysis but also promotes a shift towards data-intensive computation as the core of the “fourth paradigm” of scientific research10,11. As a result, research data has become an indispensable element of modern research, garnering widespread attention from the scientific community8,12,13.

Although research data is increasingly valued by researchers due to its unique value in the current research paradigm14,15, the extent to which this contribution is recognized by the scientific community remains inadequately quantified16. In data-intensive disciplines, for example, the time and financial resources spent on data-related work account for nearly 80% of research activities, making data work a focal point in scientific endeavors17,18. This includes not only technical operations such as data collection and pre-processing but also a deep understanding of research design, data standardization, and data management strategies19,20. Dataset curation is a core process that transforms raw records into reusable knowledge assets21. The more standardized the curation, the stronger the data’s verifiability and potential for secondary analysis, which in turn better supports subsequent research and enhances the knowledge dissemination value of the original study22. Data workers invest significant effort, equipment, and funding in the collection and organization of research data, hoping to gain professional recognition, funding support, and academic reputation through their data-related work23. However, traditional academic recognition systems largely center on publications: the primary beneficiaries are the authors of papers that analyze the data24, while the contributions of data workers are often considered “invisible labor”25. Academic recognition of data work remains a critical consideration for the career development of data professionals26. The academic community is actively exploring new, fairer, and more transparent ways to acknowledge the value of data workers27. To date, several methods have been considered. For example, offering co-authorship to data contributors in research projects is a common practice to encourage the generation and sharing of data by other researchers and is seen as a major incentive27,28,29. With the emergence of data journals, researchers can publish datasets as citable items with detailed descriptions of experimental protocols and data specifications (i.e., metadata), thereby gaining academic recognition through data publication and subsequent citations30. Olfson et al. proposed the S-index, an indicator to quantify a researcher’s data impact, analogous to the h-index31. This is calculated by arranging publications that use a researcher’s shared data by citation count; the number of papers with N or more citations (N) becomes the researcher’s S-index. Journals such as Biostatistics also distribute “data badges,” marking articles with letters such as D (for data), C (for code), or R (for reproducibility) as rewards on the article’s front page, encouraging researchers to provide their research data. Each of these measures has its advantages and disadvantages. Co-authorship credit, data citations, and the S-index directly provide academic recognition for data contributors, while data badges increase the visibility of datasets and individual reputations. However, there is still a lack of evidence-based methods to recognize the contributions of data workers32, which can lead to unintentional neglect of the scientific contributions associated with these datasets, thus creating a gap in the scientific community’s understanding of the value of research data33. Therefore, assessing the recognition of data contributions within the scientific community has become an urgent issue.

Data has become the foundation of research in many disciplines, with biomedical sciences, particularly reliant on experimental and data-driven research, standing out34. Biomedical research involves a wide range of data types35, such as genomic, proteomic, clinical, and imaging data, and the diversity and complexity of these data sources make biomedicine one of the most challenging fields for big data processing36. The uniqueness of the biomedical field lies not only in the challenges inherent to the data itself but, more importantly, in the direct impact of data curation on research value. Take COVID-19 viral genome sequencing as an example: viral data requires core team members to conduct critical curation, including sequence standardization and annotation of mutation sites, which forms the foundation for vaccine development37. Such research outcomes, due to high-quality data, are rapidly published in top journals like Nature38. Due to these characteristics, the potential for data analysis in biomedicine is vast, holding promise for breakthroughs in personalized medicine, disease diagnosis, and treatment39. The quality of data curation directly determines whether a study passes peer review, and core members leading curation efforts often receive more prominent authorship due to this key contribution, establishing a direct link between academic credit and contributions to data curation. Based on these features, we selected the biomedical field as the discipline for our sample collection to explore the role and recognition of data contributors. Authorship in a publication is the most obvious way to assess each participant’s contribution to a project according to contemporary scientific standards. Typically, data workers gain recognition within their research teams for their data-related scientific activities but are not necessarily represented as co-authors. Thus, this paper attempts to investigate the recognition of data contributions through quantitative analysis from the perspective of data worker authorship. The aim is to reveal researchers’ attitudes toward data work and clarify the value of such work in scientific research, which will likely provide new insights into the scientific community’s perception of the role of data in scientific discovery. Specifically, we seek to address the following questions:

Q1: To what extent has data-related work in biomedicine been recognized academically within research teams?

Q2: How has academic recognition of data-related work evolved (2010–2022)?

Q3: Is there a difference in the emphasis placed on data work across studies at varying research levels in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)?

Methods

Sample collection

This study quantitatively explores the academic recognition of scientific data in current scientific research by determining the relationship between the authors of datasets and the associated original papers. In the biomedical field, academic paper author order is primarily determined by contribution assessment, generally following a descending order of contributors. Typically, first authors are regarded as the main contributors to the research, while corresponding authors oversee the entire project and ensure the accuracy and integrity of research outcomes40. Drawing on this disciplinary consensus, our study infers authors’ roles in data-related work through their position in the author order. The first step in this process is to map the datasets to their related papers. The NCBI’s GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) database provides relevant information for this task. As a globally significant research data platform in the biomedical field, GEO specifically supports the storage, sharing, and analysis of gene expression and functional genomics data, showcasing the structure and visualization of gene expression data. The original data contributors (research teams) are the primary executors41. They must strictly adhere to GEO’s MIAME (Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment) standards, undertaking core curation tasks such as data preprocessing, detailed metadata annotation, and conversion of raw files into standard formats. They bear primary responsibility for data quality. The GEO database team plays only a supportive role. They are responsible for checking format compliance and correcting obvious logical errors, but do not participate in data cleaning or in-depth processing. In the GEO database, the GSE (GEO Series) metadata entry is used to describe a series of experiment-related information, designed to provide users with a complete experimental design and data context, as shown in Fig. 1.

GEO Dataset Profile63.

Each GSE entry includes the following key information: Citation(s): the original papers related to the dataset. Researchers who submitted the dataset to GEO for sharing are credited here, and the association between the dataset and its related papers is formed when these papers cite the dataset. Thus, in our study, the articles mentioned in the Citation(s) of a specific dataset correspond to the original research for this dataset. Contributor(s): the data workers referenced in this paper, defined as researchers or teams directly involved in the generation, analysis, or submission of the dataset. Status: refers to the availability and public status of the dataset, with the accompanying date indicating the time of dataset publication. Title: a concise overview of the primary research question or purpose of the experiment, enabling users to quickly grasp the research scope of the dataset. Experiment Type: the technique or method employed in the experiment, for example, “Expression Profiling By High-Throughput Sequencing.”

Not all datasets have corresponding “original papers.” According to the GEO description of Citation(s), datasets with original papers are cited at least once in their associated research papers, meaning that datasets not cited in any publication usually lack available original research papers. To efficiently filter datasets with associated original papers, we used regular expressions to extract dataset accession numbers (i.e., dataset IDs in the NCBI repository) that were mentioned at least once from the open-access (OA) subset of PMC (PubMed Central), which allows free bulk downloads of full-text articles. These datasets were then selected as the sample for this study given PMC’s status as a widely recognized indexing platform in the biomedical field, encompassing a broad range of academic biomedical journals.

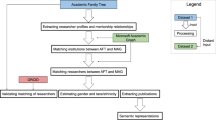

As shown in Fig. 2, the sample and data collection process consists of three main parts: dataset extraction, series (GSE) retrieval and dataset sample collection, and the collection of original papers.

Step 1: Dataset extraction

The dataset extraction in this study was based on the full-text articles from the OA subset of PMC. Regular expressions were employed to extract dataset accession numbers42. Specifically, we used the FTP service interface provided by PMC to batch download the file packages from the “oa_package” folder containing articles published before 2020. Basic information about the articles was retrieved from the index files, and the full-text articles in NXML format (2,687,283 in all) were extracted from the local file packages. To ensure easy retrieval, citation, and cross-referencing, GEO assigns a unique identifier to each dataset, referred to as the accession number. The structure of a GEO identifier typically includes a prefix followed by a series of numbers. For example, dataset identifiers start with “GDS” (GEO DataSet) or “GSE” (GEO Series), followed by a numeric string. In addition to individual dataset mentions, some articles refer to a range of datasets, such as “GSE26488 to GSE26759” or “GPL25364 to GPL25369,” which we also accounted for in the regular expression patterns. To capture all dataset samples, we employed a set of regular expressions, shown in Table 1, to identify all accession numbers from the GEO database within the full-text articles. In the end, 87,211 GEO datasets, were identified from the 2,687,283 articles.

Step 2: Series (GSE) retrieval and dataset sample collection

GEO currently stores five types of data: platform (GPL), sample (GSM), series (GSE), dataset (GDS), and Profile. The first four data types have unique accession numbers within GEO and are interrelated. For example, a platform can be referenced by multiple samples submitted by different researchers, a sample is generated based on a single platform but can be included in multiple series, and datasets are often the result of reanalysis and combination of series data by GEO staff. Profiles are expression profiles of different groups within datasets, and GEO assigns them sequential numbers, such as 33759453. Since profiles are subsets of datasets, only datasets with unique accession numbers are identified in this study. The number of each type of GEO dataset identified is shown in Table 2. Based on the relationships between different data types in GEO, the GSE corresponding to each GPL, GSM, and GDS was retrieved; Table 2 also shows the number of GSE accession numbers corresponding to each data type. After removing duplicates, the final GSE list contained 116,176 datasets, spanning the years 2001–2023. Using the GSE accession numbers, we applied automated scripts to extract key information for each dataset from the GEO database, including the contributors’ names (Contributor(s)), titles (Title), publication dates (Status), and the associated original papers (Citation(s)).

Step 3: Collection of original research papers

To trace the initial use of datasets in publications, we use the Citation(s) obtained previously to extract the PMID (the unique identifier of papers in PubMed) of the original papers. Using the list of PMIDs obtained, we further extracted the digital object identifiers (DOIs), publication dates, author lists, and journal names of the original papers from PubMed Central (PMC). For articles not retrievable from PubMed, we used Web of Science to supplement the bibliographic data. In total, we obtained 124,515 original papers. We excluded articles with only one or two authors (where data contributors are typically naturally listed as first or corresponding authors, which may not objectively reflect recognition for data work) as well as consortium-authored articles, leaving 94,001 papers from 2001–2023 for analysis.

Matching dataset contributors with original paper authors

To determine the position of data contributors in the author list of original papers and thus evaluate how data work is recognized in research, we performed a comparison between dataset contributors and the author lists of the original papers. The process included the following steps:

-

(1)

Standardizing Author Names. GEO provides contributor names in an abbreviated format, with full last names followed by the initials of the first name. To ensure consistency with the dataset contributor format, the author names in the original papers were also converted into this abbreviated form.

-

(2)

Automated Matching. To simplify the analysis and focus on the main contributors to the dataset, only the first three contributors listed for each dataset were selected for comparison. After converting the author names to abbreviated format, automated scripts were used to compare the dataset contributor names with the author lists from the original papers. A successful match was defined as an exact match between the full last name and the first initial of the contributor and the author in the original paper. If a matched pair was found, the rank of the contributor in the original publication’s author list was recorded; if not, the contributor was recorded as “unlisted.”

-

(3)

Manual Review of Unlisted Contributors. Following the automated matching process, all contributors categorized as “unlisted” were manually reviewed. This involved checking for potential issues such as special characters, inconsistencies in abbreviations, or variations in spelling that may have led to the matching failure.

-

(4)

Sampling for Accuracy. To further ensure the accuracy of the matching results, a random sample of 500 records was manually reviewed. The results of this sample verification demonstrated an accuracy rate of 99.4%, confirming the overall precision. Finally, a total of 86,610 valid dataset-paper matched pairs were finally obtained.

Results

Sizes of data contributors’ team

When analyzing the structure and contribution patterns of research teams, team size is a critical factor. Changes in the size of data contributors’ teams may not only reflect the scientific community’s demand for efficient collaboration and specialized division of labor but also indicate shifts in how much importance research teams place on data work43. To investigate this, we calculated the size of data contributor teams by year and plotted a time series graph of the number of data contributors over time. As shown in Fig. 3, in the field of biomedicine, most datasets (approximately 61%) are submitted by small teams consisting of 2–5 members. This is followed by medium-sized teams of 6–10 members (18.90% of datasets). In contrast, single-person teams and large teams with 10 or more members are relatively rare.

Further analysis reveals that the proportion of datasets submitted by small teams has steadily increased over the years, rising from 58% in 2010 to 63% in 2023. Meanwhile, the proportion of medium-sized teams (6–10 members) has gradually decreased over time. Although the proportions of single-person teams and large teams have fluctuated slightly, they have consistently remained at relatively low levels. Small teams, with their greater flexibility and focus, tend to achieve more efficient collaboration and communication within specific fields or projects. This usually leads to advantages in data quality, processing speed, and innovation. The decline in the proportion of medium-sized teams may be related to the increasing specialization of data contribution roles. As data management processes become more complex, research teams may prefer to maintain streamlined, small-team collaborations to enhance efficiency and reduce the costs associated with management and communication.

These possible advantages and trends of small teams in contemporary biomedical data contributions imply that the academic community is increasingly emphasizing team flexibility and efficient specialized collaboration to address the growing complexity of data management and research demands.

Consistency analysis between dataset contributors and main authors of original papers

In this section, we compare the names of dataset contributors with the authors listed in the associated original papers, analyzing the positional alignment of dataset contributors within the authorship hierarchy of the original papers. As shown in Fig. 4, the first dataset contributor is frequently (80.62% of datasets) listed as a primary author (either first or corresponding author) of the original research papers. This indicates that the first dataset contributor plays a central role not only in dataset generation but also in the research design, data analysis, and manuscript writing44, making them a key driver of both the research project and the resulting publication. For the second and third dataset contributors, the proportions of being listed as main authors in the original research papers are lower: 31.97% and 20.33%, respectively. The roles of these contributors tend to shift toward secondary authorship, with 16.5%, 62.86%, and 72.52% of the first, second, and third contributors, respectively, being listed as secondary authors (i.e., not first or corresponding authors). For cases where dataset contributors are not listed as authors in the original papers, statistics show that more than half of the datasets have multiple papers listed in the Citation(s). This can largely be attributed to the update mechanism within the GEO database. If researchers conduct a new series of experiments and wish to add new data to an existing dataset, they can update the dataset and add new papers to the Citation(s). While the new papers may have some overlap in authorship with the original research, they are not entirely identical. This suggests that different members of the same research team may, at a later stage, conduct new experiments based on the dataset and publish further academic findings. In these cases, the contributors of the updated dataset might replace the original dataset contributors in terms of involvement and thus earn authorship in the subsequent papers.

Although the above results indicate that the first contributor of a dataset often holds a central authorial role in the research (as the first or corresponding author of the paper), this cannot be solely attributed to their data contribution. One possible explanation is that data contributors also take on other key responsibilities within the research, such as conceptual development and experimental design. Therefore, to further explore the influence of data contributions on authorship, we randomly selected 500 datasets and their original studies from the entire dataset sample. We focused on original research papers that included data contribution statements and analyzed the specific contributions of these dataset contributors to the research. The results show that when dataset contributors held major responsibilities in the original papers, nearly 90% (479) of the researchers were involved in either data analysis or manuscript writing in addition to data collection. This suggests that data collection is closely linked to experimental design, as data collectors often need to fully understand the experimental design process to effectively align data collection with research objectives. When dataset contributors were listed as secondary authors in the paper, they mostly handled data collection and analysis and were less involved in the conceptualization and writing of the paper.

Evolution of the academic roles of data contributors

To illustrate the trends in the responsibilities assumed by dataset contributors over time, we plotted the changes in their authorship positions relative to the dataset submission year. Figure 5(a) depicts the proportion of datasets in which the first contributor held different responsibilities over time. The blue and red lines represent the first contributor’s role as the first author and corresponding author, respectively, in the original papers. Over the past decade, both lines show an upward trend, indicating that the first contributors are increasingly likely to continue playing a major role in the paper. The green line illustrates the trend for the first contributor serving as secondary authors. This trajectory has shown a decreasing trend over the years, further confirming that first contributors are increasingly assuming primary responsibilities in papers. Additionally, the proportion of cases where the first contributor is unlisted as an author remains consistently low. Figure 5(b,c) depict the trends in the roles of second and third contributors over time. The patterns for these contributors are very similar: both are primarily listed as secondary authors in papers, with this proportion significantly higher than for first or unlisted authors. However, this proportion has slightly declined in recent years. Meanwhile, the proportion of second and third contributors being listed as first or corresponding authors has shown a slight increase, suggesting a gradual rise in their academic standing. This trend indicates that secondary contributors to datasets may be gradually shifting from secondary roles to more prominent academic positions.

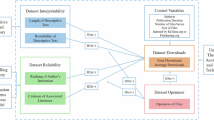

Authorship variations of data contributors across research levels

To explore whether there are potential differences in the recognition of data work across various research levels, we used the impact factor of the journals (JIF) where the original research was published. JIF is widely regarded as an indicator of research significance, as higher-impact journals typically publish more scientifically valuable and influential research, reflecting stricter peer review and authorship practices45,46. In the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) released by Clarivate, the citation data for core journals included in the Science Citation Index (SCI) is statistically analyzed and computed to derive each journal’s impact factor. Based on these calculations, journals are then categorized into four quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4). Q1 journals (top 25% by JIF) are considered more influential than Q2 journals, and so on. A journal may be classified into multiple categories, meaning it can belong to different JIF quartiles depending on the field47. In this study, we used the highest JIF quartile classification for multi-category journals and counted the number of datasets for each authorship position in the various quartiles.

Figure 6 depicts the proportion of datasets in which the first contributor assumes different roles in papers across journal quartiles. In all quartiles, the proportion of cases in which the first dataset contributor takes on main authorship roles (first or corresponding author) consistently exceeds 81%, indicating that the first dataset contributor is generally well-recognized regardless of the journal’s impact factor. As journal impact increases, the proportion of first dataset contributors serving as first authors rises, with Q1 journals having the highest proportion at 58.48%. However, the proportion of the first dataset contributor acting as corresponding authors is highest in Q4 journals, at 33.53%, followed by Q3 at 32.36%, which is higher than Q1 (23.26%) and Q2 (26.26%). The proportion of the first dataset contributor assuming secondary authorship also decreases as journal impact increases. The proportion of first dataset contributors who are unlisted in the original publication is lowest in Q1 journals, followed by Q4 at 3.59%, while Q2 and Q3 have slightly higher unlisted proportions at 4.74% and 3.69%, respectively.

To verify whether these findings have statistical significance, we performed a Chi-square (χ2) test on the number of papers where the first dataset contributor assumed different responsibilities across journals of varying impact factors. The resulting Pearson Chi-square statistic is 142.329, with 9 degrees of freedom and a p-value less than 0.001. This p-value is significantly lower than the significance level of 0.05, indicating that there are statistically significant differences in the authorship order of primary dataset contributors across journals with different levels of impact.

Discussion

This study provides a deeper understanding of the role and value of data work in the scientific process and highlights the critical role data plays in scientific discovery. By quantitatively analyzing the recognition of data contributions through authorship, we specifically explored the degree of academic recognition for data contributions and its trends over time, as well as the differences in emphasis on data contributions across research of varying levels.

Broader recognition of the importance of data work to modern research

In biomedical research, the first author is typically regarded as the major contributor to the study, while the corresponding author is responsible for overseeing the entire project, ensuring the accuracy and completeness of the research results40. The results of this study show that the first contributor of datasets assumes these key roles in the original papers 80% of the time, indicating that data-related work plays an irreplaceable role in the research process (Q1). This also reflects the fact that data has transcended its role as a simple tool for supporting research conclusions and has become a core driver throughout the research process from formulating research questions and choosing methods to validating hypotheses. Data has become the foundation that drives scientific progress. In contrast, the second and third dataset contributors are usually secondary authors in the paper and are more likely to be unlisted in the original research. This may be because those dataset contributors typically focus on specific data processing and analysis tasks and are less involved in the overall conceptualization and drafting of the paper.

It is important to note that the rules of authorship remain largely based on contributions, a traditional practice that, although effective in many cases, may fail to fully reflect the contributions of all data workers, especially in the context of multidisciplinary collaboration and data-driven research. As scientific research increasingly relies on large-scale datasets, the complexity and specialization of data work have grown, and traditional metrics for authorship and recognition may not fully capture the true contributions of data workers48,49. This imbalance may diminish the motivation of data scientists within research teams, thereby affecting their willingness to share data and collaborate50. Therefore, revisiting the rules of academic authorship, particularly the criteria for recognizing data contributions, should become a focal point for the academic community. Introducing new metrics such as dataset citations or contribution scores could provide a fairer and more transparent way to recognize data contributors, further promoting data sharing and open innovation in scientific research. The recognition of the value of data work in the scientific community is a positive signal, especially in the biomedical field, where the academic standing of data contributors is gaining more acknowledgment.

Our analysis of authorship patterns reveals that the main contributors to data work, particularly the first contributor, generally receive appropriate academic recognition. This acknowledgment underscores their pivotal role in the research process, not only in experimental design, data collection, and execution but also as an essential force driving scientific progress. The academic recognition of data work is not only a validation of individual contributions but highlights the critical role that data plays as a catalyst for knowledge creation and innovation in the modern research environment. This recognition will continue to push data-driven research paradigms forward by encouraging data scientists to constantly commit to data work which will lay a solid foundation for the future development of science. Such work also enables various disciplines to achieve greater advances within the global scientific community, fostering continuous knowledge accumulation and technological innovation.

Data work: moving from periphery to center

The results of this study indicate that the academic recognition of data-related work has been increasing year by year. In particular, the academic status of the first dataset contributor is rising, with more of these contributors assuming first-author roles in papers; this suggests that the scientific community is gradually recognizing data collection, processing, and analysis as core elements of the research process (Q2). Data work is no longer merely a technical support task; it has become a key factor driving scientific discovery. Furthermore, while the second and third dataset contributors still mostly serve as secondary authors, their contributions are increasingly being recognized, with more data contributors being listed as major participants in research. This shift reflects a broader change in how research contributions are evaluated, with a growing emphasis on recognizing dimensions that range from experimental design to data processing. Each stage of the research process is gradually being incorporated into a more comprehensive evaluation system. It also suggests that future scientific research will increasingly rely on high-quality data work, which will play a fundamental role in further scientific advancements.

Our quantitative analysis demonstrates that the academic recognition of data work is undergoing a transformation from the periphery to the core. In the Middle Ages, science was only considered valid and credible when a noble figure attached their name to a paper, even if they had made no real contribution to the research51. By the 17th and 18th centuries, the rights of scientific authors became tied to copyright and authorial rights in Europe and the United States52. In the U.S., the concept of intellectual property emphasized the importance of “originality,” linking it to individual inventors who could independently generate innovative ideas and thereby excluding the value of collaborative work52. However, as interdisciplinary knowledge integration has advanced, more researchers are overcoming the limitations of their own knowledge and skills through collaboration, consistently producing high-quality research. Contributions related to data, which have historically been overlooked in authorship attribution, have begun to receive more attention, especially in data-intensive sciences where tasks such as data cleaning were previously undervalued as “non-scientific work”53. As open science and data-sharing movements progress and the academic community places more emphasis on data management and reusability, the stance of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) on data sharing has evolved. Before the 2000s, ICMJE recommendations stated that authorship required “substantial contributions to the conception and design, or the analysis and interpretation of data,” and data collection alone was not considered sufficient for authorship54. In May 2000, the guidelines were revised to place more importance on data acquisition55; in the August 2013 version, the statement that data collection alone was insufficient for authorship was removed56, and by 2017, generating, contributing, and sharing data were recognized as highly commendable actions57. In this evolving environment, data scientists, statisticians, and computer scientists, previously considered non-traditional research roles, are gradually gaining higher academic status, with data work rising from the periphery to the core of the research process58.

Better data, better science

High-impact journals usually select research outcomes through rigorous peer review, and the studies they publish are generally regarded as representing higher scientific quality in dimensions such as data reliability, conclusion reproducibility, and academic influence45. Therefore, journal impact, although not perfect, can be considered a reasonable indicator of research quality. The results of this study show that in high-impact journals, the first dataset contributor is more likely to be listed as the first author and less likely as the corresponding author (Q3). In those journals, data is often regarded as an independent and core research element, and the work typically entails greater investment by teams, including more resources and effort devoted to experimental design, data collection, and subsequent processing. As the investment increases, the quality of the data significantly improves because of well-designed and executed data work that supplies more reliable and representative datasets. Ultimately, high-quality data not only provides the foundation for research but also enhances the credibility and academic impact of the research findings, leading to better research outcomes. In other words, the emphasis placed on data by high-quality journals motivates research teams to invest more resources in data collection and processing. This standardized data-related work enhances the scientific quality of the research, thereby meeting the publication standards of high-impact journals, which indirectly supports the claim that “better data, better science.” For researchers, high-quality data curation demonstrates research rigor, making it easier to meet the publication standards of high-impact journals and thereby gaining academic visibility through publication59.

In lower-impact journals, the proportion of first dataset contributors serving as corresponding authors is higher, suggesting that they are not only responsible for data collection and processing but may also take on broader roles in research management, coordination, and team organization60. This indicates that data work in these studies is more closely tied to overall research input, rather than being viewed as the core element of the research itself60. Our findings indicate that, as scientific research becomes increasingly data-driven, high-quality data has emerged as a central resource for driving scientific discovery and innovation. It not only helps researchers identify potential scientific phenomena but also ensures the reliability and reproducibility of research findings. The precision and rigor of data work directly determine the scientific validity of research conclusions, leading to higher-quality research. As the complexity of research increases, high-impact scientific studies often involve the handling of large-scale and complex data, which imposes more stringent requirements on data quality. Complex research designs and analyses rely on accurate and comprehensive data support, and any flaws in the data could lead to unreliable or irreproducible results. Therefore, the accuracy, completeness, and rigor of data handling have become key factors in ensuring the validity and credibility of research findings.

Although the acceptance criteria for papers in high-impact journals prioritize the overall value of the research, the originality and credibility of research conclusions have always been partially dependent on standardized and reliable data support61. If data curation fails to meet standards, the reproducibility of research conclusions will be significantly reduced, making it hard to pass strict peer review. However, this study does not claim that journal acceptance is directly equivalent to targeted recognition of data work. The acceptance of a paper still primarily depends on the overall value of the research, and data contribution is an important rather than the sole factor supporting this value.

Conclusion

The findings of this study demonstrate that the majority of dataset contributors play significant roles in academic research, and their scientific contributions are largely recognized by their research teams. This highlights the critical importance of data generation and management in the overall success of scientific research, emphasizing the central role of data contributors in the formation of academic outcomes. An interesting discovery in our statistical results is that the primary contributors of datasets often take on additional key responsibilities, such as experimental design, data analysis, and manuscript writing, placing them in prominent authorial roles within the papers. This observation underscores the importance of deeper engagement in the broader research process for researchers involved in data work, as such involvement is crucial for gaining greater academic recognition. Furthermore, it suggests that data-related researchers must possess broader and more in-depth scientific knowledge and skills to make a more substantial impact on research.

Whether in basic or applied sciences, the collection, analysis, and processing of data play crucial roles throughout the research process. The central role of data work in modern scientific research is undeniable. The recognition of such work in the scientific community is reflected not only in the authorship positions of data contributors but also in the way data ensures the reliability and innovation of research findings. Looking ahead, as data-driven research continues to evolve, the contributions of data workers will become even more closely integrated into all stages of scientific discovery, driving further innovation and fostering broader academic collaboration.

In this study, our primary focus is on providing empirical insights into the role of data work within research teams by examining the patterns of overlap between core contributors to a paper and core contributors to the corresponding dataset. Through the statistical examination, we have indeed observed this phenomenon of contributor overlap. In a separate, ongoing study, we are leveraging author contribution statements from primary literature to explore more granularly the relationship between authorship and specific data work. However, to fully understand the specific causes and mechanisms underlying these observed high-overlap patterns, future research should integrate qualitative methods, such as interviews and surveys with research team members, to obtain direct evidence regarding the actual distribution of contributions and the processes involved in authorship decisions.

This study exclusively utilized datasets from GEO due to their unique capacity to link raw data to source publications with explicit contributor attribution. Although GEO is the most widely adopted biomedical data repository, 90 interpretations require caution regarding disciplinary contexts. Biomedical authorship conventions, influenced by collaborative research models and institutional data policies, may disproportionately recognize data contributions compared to fields where data production is decentralized or tool-driven. More efforts are necessary to examine discipline specific mechanisms for crediting data contributions and broader validation across research cultures remains essential to understand academia’s evolving recognition of data labor.

Data availability

The raw data examined in this research is available at Figshare repository62 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28425119.v1).

Code availability

The code used in this research is shown in Table 1.

References

Grossi, V. et al. Data science: a game changer for science and innovation. Int J Data Sci Anal. 11, 263–278 (2021).

Lin, Z., Yin, Y., Liu, L. & Wang, D. SciSciNet: A large-scale open data lake for the science of science research. Sci Data. 10(1), 315 (2023).

Wamba, S. F., Akter, S., Edwards, A., Chopin, G. & Gnanzou, D. How ‘big data’ can make big impact: Findings from a systematic review and a longitudinal case study. Int J Prod Econ. 165, 234–246 (2015).

Manyika, J. et al. Big data: The next frontier for innovation, competition (Vol. 5, No. 6) and productivity. (Technical report, McKinsey Global Institute, 2011).

Ramalli, E. & Pernici, B. Challenges of a Data Ecosystem for scientific data. Data Knowl Eng. 148, 102236 (2023).

Iqbal, R., Doctor, F., More, B., Mahmud, S. & Yousuf, U. Big data analytics: Computational intelligence techniques and application areas. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 153, 119253 (2020).

Hirsch, D. D. The glass house effect: Big Data, the new oil, and the power of analogy. Maine Law Rev. 66, 373 (2013).

Guo, H. Big data for scientific research and discovery. Int J Digit Earth. 8(1), 1–2 (2015).

Nobel Prize Outreach AB. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2024 - Prize announcement. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2024/prize-announcement/ (2024).

Tansley, S. & Tolle, K. M. in The fourth paradigm: data-intensive scientific discovery Vol. 1. T. Hey (Ed. Tony, H.) (Redmond, WA: Microsoft research 2009).

Bibri, S. E. The sciences underlying smart sustainable urbanism: unprecedented paradigmatic and scholarly shifts in light of big data science and analytics. Smart Cities. 2(2), 179–213 (2019).

Brodie, M. L. Defining data science: a new field of inquiry. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.16177 (2023).

Belter, C. W. Global-level data sets may be more highly cited than most journal articles. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences (2014).

Tenopir, C. et al. Changes in data sharing and data reuse practices and perceptions among scientists worldwide. PloS One. 10(8), e0134826 (2015).

Chang, Y. W., Huang, M. H. & Kuan, C. H. Identifying the contribution - influence gap in the science and technology community. Proc Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 56(1), 622–623 (2019).

Hameed, M. Structural preparation of raw data files (Doctoral dissertation, Universität Potsdam, 2024).

Fayyad, U. M., ut al. Benchmarks and Process Management in Data Science: Will We Ever Get Over the Mess? In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 31–32). (2017).

Kantere, V. A holistic framework for big scientific data management. In 2014 IEEE International Congress on Big Data (pp. 220–226). (2014).

Yuan, D., Cui, L. & Liu, X. Cloud data management for scientific workflows: Research issues, methodologies, and state-of-the-art. In 2014 10th International Conference on Semantics, Knowledge and Grids (pp. 21–28) (2014).

Bierer, B. E., Crosas, M. & Pierce, H. H. Data authorship as an incentive to data sharing. New England Journal of Medicine. 376(17), 1684–1687 (2017).

Hellerstein, J. M., Heer, J. & Kandel, S. Self-Service Data Preparation: Research to Practice. IEEE Data Eng. Bull. 41(2), 23–34 (2018).

Marsolek, W. et al. Understanding the value of curation: A survey of researcher perspectives of data curation services from six US institutions. PloS one. 18(11), e0293534 (2023).

Hood, A. S. & Sutherland, W. J. The data - index: An author - level metric that values impactful data and incentivizes data sharing. BMC Ecol Evol. 11(21), 14344–14350 (2021).

He, S., Ganzinger, M., Hurdle, J. F. & Knaup, P. Proposal for a data publication and citation framework when sharing biomedical research resources. In MEDINFO 2013 (pp. 1201–1201). (IOS Press, 2013).

Davies, S. W. et al. Promoting inclusive metrics of success and impact to dismantle a discriminatory reward system in science. PLoS Biol. 19(6), e3001282 (2021).

Devriendt, T., Borry, P. & Shabani, M. Credit and recognition for contributions to data-sharing platforms among cohort holders and platform developers in Europe: interview study. J Med Internet Res. 24(1), e25983 (2022).

Devriendt, T., Shabani, M. & Borry, P. Data sharing in biomedical sciences: a systematic review of incentives. Biopreserv Biobank. 19(3), 219–227 (2021).

Lo, B. & DeMets, D. L. Incentives for clinical trialists to share data. N Engl J Med. 375(12), 1112–1115 (2016).

Ohmann, C. et al. Sharing and reuse of individual participant data from clinical trials: principles and recommendations. BMJ Open. 7(12), e018647 (2017).

Kaye, J., Heeney, C., Hawkins, N., De Vries, J. & Boddington, P. Data sharing in genomics–re-shaping scientific practice. Nat Rev Genet. 10(5), 331–335 (2009).

Olfson, M., Wall, M. M. & Blanco, C. Incentivizing data sharing and collaboration in medical research - The s-index. JAMA Psychiatry. 74(1), 5–6 (2017).

Rowhani-Farid, A., Allen, M. & Barnett, A. G. What incentives increase data sharing in health and medical research? A systematic review. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2, 1–10 (2017).

Costas, R. & Bordons, M. Do age and professional rank influence the order of authorship in scientific publications? Some evidence from a micro-level perspective. Scientometrics. 88(1), 145–161 (2011).

LI, Y. & Chen, L. Big biological impacts from big data. Science. 12, 187–189 (2014).

Hong, L. et al. Big data in health care: Applications and challenges. Data Inf Manag. 2(3), 175–197 (2018).

Yang, X., Huang, K., Yang, D., Zhao, W. & Zhou, X. Biomedical big data technologies, applications, and challenges for precision medicine: A review. Glob Chall. 8(1), 2300163 (2024).

Kraemer, M. U. et al. Data curation during a pandemic and lessons learned from COVID-19. Nature Computational Science. 1(1), 9–10 (2021).

Pericàs, J. M., Arenas, A., Torrallardona-Murphy, O., Valero, H. & Nicolás, D. Published evidence on COVID-19 in top-ranked journals: a descriptive study. European journal of internal medicine. 79, 120–122 (2020).

Cremin, C. J., Dash, S. & Huang, X. Big data: historic advances and emerging trends in biomedical research. Curr Res Biotechnol. 4, 138–151 (2022).

Smith, E. “Technical” contributors and authorship distribution in health science. Science and Engineering Ethics. 29(4), 22 (2023).

National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/info/overview.html (2024).

Ma, X., Jiao, H., Zhao, Y., Huang, S. & Yang, B. Does open data have the potential to improve the response of science to public health emergencies? J Informetr. 18(2), 101505 (2024).

Hara, N., Solomon, P., Kim, S. L. & Sonnenwald, D. H. An emerging view of scientific collaboration: Scientists’ perspectives on collaboration and factors that impact collaboration. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 54(10), 952–965 (2003).

Shapiro, D. W., Wenger, N. S. & Shapiro, M. F. The contributions of authors to multiauthored biomedical research papers. JAMA. 271(6), 438–442 (1994).

Paine, C. T. & Fox, C. W. The effectiveness of journals as arbiters of scientific impact. BMC Ecol Evol. 8(19), 9566–9585 (2018).

Nierop, E. V. The introduction of the 5 - year impact factor: does it benefit statistics journals? Stat Neerl. 64(1), 71–76 (2010).

Vȋiu, G. A. & Păunescu, M. The lack of meaningful boundary differences between journal impact factor quartiles undermines their independent use in research evaluation. Scientometrics. 126(2), 1495–1525 (2021).

Haeussler, C. & Sauermann, H. Credit where credit is due? The impact of project contributions and social factors on authorship and inventorship. Res Policy. 42(3), 688–703 (2013).

Brand, A., Allen, L., Altman, M., Hlava, M. & Scott, J. Beyond authorship: Attribution, contribution, collaboration, and credit. Learned Publ. 28(2) (2015).

Borenstein, J. & Shamoo, A. E. Rethinking authorship in the era of collaborative research. Account Res. 22(5), 267–283 (2015).

Chartier, R. Foucault’s chiasmus: Authorship between science and literature in the seventeenth and eighteenth Centuries. In Scientific authorship: Credit and intellectual property in science (eds. Biagioli M. & Galison P.) (pp. 13–31) (Routledge, 2003).

Jaszi, P. & Woodmansee, M. Beyond authorship: refiguring rights in traditional culture and bioknowledge. In Scientific authorship (pp. 195–223) (Routledge, 2014).

Plantin, J. C. Data cleaners for pristine datasets: Visibility and invisibility of data processors in social science. Sci Technol Human Values. 44(1), 52–73 (2019).

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals. Pathology. 29(4), 441–447 (1997).

Huth, E. J. & Case, K. The URM: twenty-five years old. Science Editor. 27(1), 17–21 (2004).

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing and publication of scholarly work in medical journals. http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/archives/ (2013).

Elbe, S. & Buckland-Merrett, G. Data, disease and diplomacy: GISAID’s innovative contribution to global health. Glob Chall. 1(1), 33–46 (2017).

Tuan Zakaria, T. N. Is data scientist still the sexiest job for 2024? What’s What PSPM. (2024).

Piwowar, H. A. & Vision, T. J. Data reuse and the open data citation advantage. PeerJ 1, e175 (2013).

Chinchilla-Rodríguez, Z., Costas, R., Robinson-García, N. & Larivière, V. Examining the quality of the corresponding authorship field in Web of Science and Scopus. Quant Sci Stud. 5(1), 76–97 (2024).

How High-Quality Data Sources Enhance Research Productivity. IEEE, https://ieee-dataport.org/news/how-high-quality-data-sources-enhance-research-productivity (2025).

Liua, J. et al. How does academia recognize the contribution of scientific data? Evidence from data contributors’ authorship. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29453042 (2025).

National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE21067.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China [grant number 24BTQ040] and Qing Lan Project of Jiangsu Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiaxue Liu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Xiaowei Ma: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Hong Jiao: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Yuhong Qiu: Data curation, Investigation. Tong Niu: Visualization, Software. Bo Yang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Ma, X., Jiao, H. et al. How does academia recognize the contribution of scientific data? Evidence from data contributors’ authorship. Sci Data 13, 26 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06340-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06340-7