Abstract

We present a unique dataset of chronic wireless electrocorticography (ECoG) recordings obtained from two fully implanted nonhuman primates (adult Japanese macaques, Macaca fuscata) spanning hundreds of days post implantation. Each animal was equipped with bilateral subdural ECoG arrays targeting the sensorimotor cortices and a fully implantable wireless transmission unit. The dataset involves multiple tasks, including resting-state measurements, auditory listening paradigms, voluntary button presses, reaching movements, and somatosensory evoked potentials, providing a broad range of behavioural and stimulus conditions. All raw signals, event annotations, and metadata are organized according to the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) extension for intracranial electrophysiology, ensuring ease of reuse and interoperability with common neurophysiological software. We verified the data quality and stability through impedance monitoring, power spectral analyses, and task-specific event-related measures across the recording period, confirming the reliability and consistency of the ECoG signals. By offering open access to these longitudinal wireless ECoG data, we aim to facilitate the acquisition of new insights into long-term cortical dynamics and advance brain–computer interface (BCI) research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Electrocorticography (ECoG) has been widely utilized in clinical and research applications because of its ability to record brain activity with high spatial and temporal resolution1,2,3. Compared with scalp electroencephalography and intracortical microelectrode recordings, ECoG achieves a good balance of spatial resolution, coverage area, and signal stability, making it a powerful modality for understanding the large-scale organization of cortical networks and extracting neural information that can be used in brain–computer interfaces (BCIs)4. However, traditionally, ECoG has been used to measure cortical signals in short-term experimental and clinical settings, such as epilepsy monitoring and functional mapping during surgery5,6.

In recent years, the development of fully implantable, wireless ECoG devices has opened new avenues for long-term monitoring of freely behaving subjects, overcoming the constraints of cables and potentially yielding richer insights into brain function and enabling stable daily use by severely paralyzed patients7,8. Several studies have demonstrated that ECoG-based implants can maintain stable neural recordings for months or even years9,10, underscoring their potential in chronic BCI use. In humans, chronic ambulatory ECoG likewise enables long-term intracranial monitoring and clinical lateralization11,12. Despite these advances, there remains a lack of publicly available, large-scale datasets acquired from truly wireless ECoG systems; such datasets are crucial for understanding the long-term stability of cortical signals across diverse behavioural tasks. These datasets could significantly broaden the insights into continuous neural dynamics and accelerate the development of robust decoding algorithms for BCIs and neurorehabilitation applications.

To address this research gap, we conducted a series of experiments on two adult Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) to collect comprehensive wireless ECoG data across a range of tasks involving auditory processing, voluntary button presses, reaching movements, and somatosensory stimulation. Both monkeys were surgically implanted with a fully implantable, bilateral ECoG system targeting the sensorimotor cortex. This approach enabled us to track cortical activity over extended periods while minimizing the impact of external wiring. By employing a combination of resting-state measurements, impedance checks, listening tasks, pressing tasks, reaching tasks, and somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs), we acquired a multifaceted dataset that characterizes the functional state of the sensorimotor cortex under varying behavioural and stimulus conditions.

We believe that researchers aiming to advance BCIs or develop novel decoding algorithms can benefit from the longitudinal and wireless recordings of these ECoG signals. The diversity of tasks, spanning auditory and motor domains, provides opportunities to study cross-modal and motor-network interactions through a single dataset. Furthermore, SEPs provide a robust benchmark for validating electrode functionality over time and under different conditions. By making these data publicly available, we hope to facilitate new inquiries into the neural underpinnings of sensorimotor integration, accelerate comparative analyses of other species and modalities, and drive methodological innovations in wireless neurotechnology and long-term cortical recording.

This article describes the implantation procedure, experimental protocols, data structure, and technical validation of the recorded signals, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers seeking to investigate chronic cortical recordings in nonhuman primates. We anticipate that this wireless ECoG dataset—obtained from a rarely studied macaque species—will be a valuable resource for ongoing and future work in nonhuman primates modelling and translational BCI design.

Methods

Subjects

Two adult female Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) were obtained from the National BioResource Project (NBRP), Japan. The animals, referred to as Monkey C and Monkey B, were approximately eight years of age and weighed 6.3 kg and 5.9 kg, respectively, at the time of surgery. All animal procedures complied with Japanese laws and institutional regulations, including the Science Council of Japan Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiment, and were approved by the Animal Experiments Committee — The University of Osaka (approval number: FBS-25-002). In the approved animal experiment protocol, humane endpoints were predefined as ≥25% body weight losses within 7 days or unrelieved moderate–severe pain, at which the animal was to be euthanized with intravenous (IV) injection of secobarbital 120 mg/kg followed by exsanguination.

The monkeys were single-housed in a 710 mm of depth × 800 mm of width × 1195 mm of height cage under controlled conditions (24 °C, ~60% RH, lights on from 08:00–20:00) with water ad libitum, 100–120 g of PS-A chow (Oriental Yeast Co., Japan), fresh fruits daily, environmental enrichment and regular veterinary check-ups. Both behavioural training and experimental sessions were performed in a dedicated facility to minimize external disturbances.

Perioperative care

After Twelve-hour preoperative fasting, anaesthesia was induced to animals first with ketamine (5 mg/kg) intramuscularly (IM) and xylazine (1 mg/kg IM), and then buprenorphine 0.02 mg/kg, ampicillin 25 mg/kg, maropitant 0.1 mg/kg, and atropine 0.04 mg/kg were administered subcutaneously (SC). After effective general anesthesia was confirmed, animals were transferred to the operating room, intubated and placed on the heating pad set at 38 °C. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane and the carrier O₂/air gas via endotracheal tube; with continuous heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), saturation of percutaneous oxygen (SpO₂), end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO₂), and core body temperature monitoring.

After the surgery was completed, animals were induced to have spontaneous breathing and purposeful movement and returned to their housing cage. As postoperative care, ampicillin 25 mg/kg SC, maropitant citrate 2 mg/kg SC, and dexamethasone 0.1 mg/kg IM were administered twice daily for the subsequent 3 days.

No surgical complications or adverse events have been observed to date.

Implantation of the ECoG Device

Device description

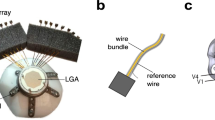

A fully implantable wireless ECoG device (Brain Interchange ONE, CorTec GmbH, Freiburg, Germany) was surgically implanted in each monkey (Fig. 1). The ECoG electrodes consisted of two subdural sheets, each containing 16 electrodes, arranged bilaterally over the sensorimotor cortex (Fig. 1a). Each array comprised 15 measurement electrodes and one reference electrode facing the dura mater. The electrodes were platinum, with a diameter of 1.5 mm and an interelectrode spacing of 5 mm. The primary electronics unit was implanted subcutaneously in the monkey’s back and was connected to the electrode arrays via subcutaneous leads, enabling wireless data transmission to an external receiver (Fig. 1b).

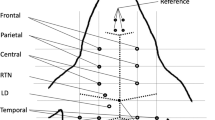

An illustration of the fully implanted wireless EEG system (Brain Interchange ONE, CorTec GmbH) and a schematic drawing of a macaque cortex with the electrode location (a). Brain interchange system with customized ECoG electrode arrays used in the present study (the cable lengths between the arrays and the implant body were longer in the actual implant and are shortened for representation in this diagram) (b). General operating principle of the brain interchange system. This is a schematic depiction of the implanted and external components used to operate and control the device via software and APIs installed on the acquiring computer. c and d) Schematic representations of the macaque cortex in the top (c) and lateral (d) views, illustrating the location and coverage of the ECoG array, which were identical across both monkeys. The array was positioned relative to the central sulcus, whose location was inferred from a prominent surface vein that was presumed to follow the course of the sulcus. Each array comprised 15 recording electrodes (shown in blue) and one reference electrode facing the dura mater (shown in orange). It contained two columns of electrodes over the precentral gyrus and one column over the postcentral gyrus, and extended partially towards the temporal cortex. Electrode footprints were manually registered to the standard cortical atlas, with the electrode geometry rescaled to match the spatial scale of the atlas. Representative electrode labels indicate the numbering scheme across the array. Scale bars and anatomical orientation markers were included to facilitate spatial interpretation. Panel c served as the global spatial reference for all subsequent topographic maps, which shared the same orientation and electrode arrangement scheme.

Surgical procedure and electrode localization

Bilateral craniotomies were performed to place the ECoG sheets over the primary motor and somatosensory cortices. For both subjects, the targeting process was guided by skull landmarks. The coronal suture and bregma were identified, and the centre of the craniotomy was estimated at approximately 1 cm posterior and 1.5 cm lateral to the bregma. A 2 cm × 2.5 cm craniotomy was performed on each hemisphere, with the medial edge approximately 5 mm lateral to the midline. The dura was opened in a lateral-based U shape to expose the cortical surface.

A prominent surface vein presumed to follow the central sulcus was used to distinguish the precentral gyrus from the postcentral gyrus. The ECoG array was positioned such that two columns covered the precentral gyrus and one column covered the postcentral gyrus, thereby covering both motor and somatosensory regions. The electronics unit (component 3 in Fig. 1b) and ground electrode (component 2 in Fig. 1b) were implanted subcutaneously on the dorsal region, approximately 2 cm left of the midline and just inferior to the scapular margin, within a pocket that was superficial to the dorsal fascia.

The functional localization procedure was aided by intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring when feasible. In Monkey C, during the first implantation, bipolar stimulation did not evoke overt motor responses. Therefore, in Monkey B, during the second implantation, additional somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) delivered via needle electrodes were recorded during the median nerve stimulation process to assist with cortical localization. These intraoperative recordings revealed clear cortical SEPs in response to median nerve stimulation and, together with bipolar stimulation, evoked responses involving the face and shoulder, confirming that most electrode contacts were positioned over the sensorimotor cortex. Furthermore, on the basis of experience obtained from the first implantation process, the second surgery incorporated several mechanical refinements to improve stability. The head stabilization was enhanced by substituting infraorbital fixation with mandibular support, and additional grooves were created to secure the leads.

To visualize the electrode positions, schematic overlays were reconstructed using the macaque MRI and DTI atlas13. The electrode footprints were manually aligned using surgical landmarks and actual contact geometry (intercontact spacing and column pitch information) on the same spatial scale as that of the atlas reconstruction process.

Data acquisition system

Custom C++ software was developed to record and integrate neural and external signals. The system simultaneously acquired ECoG signals from the implant and external signals from a high-speed digital I/O board (LPCIe-7230, ADLINK Technology, Taiwan) equipped with 16 digital input channels.

The implant contained built-in amplifiers operating at a gain of 59.5 dB, sampling signals at 1 kHz. The electrode array was designed with the recording contacts facing the cortical surface and an integrated reference electrode on the reverse side facing the skull. The ground electrode was implanted subcutaneously in the dorsal region and served as the common ground for all the channels. Each ECoG sample was assigned an incrementing index counter generated by the implant, providing a precise time base and enabling the post-hoc detection of data losses. The signals were digitized and transmitted wirelessly to an external receiver unit, which communicated with the recording computer via USB in the batch transfer mode.

For each received sample, the acquisition software immediately queried the 16-channel digital input state from the I/O board through the API of the manufacturer and stored the digital values together with the corresponding ECoG sample. This operation established software-level alignment between the ECoG and external digital signals. In ex vivo validation, the latency between ECoG sampling and digital input acquisition was measured as mean ± SD = 3.56 ± 1.57 ms (95th percentile = 6.00 ms, maximum = 14.00 ms; N = 993 events, 22.45 min), indicating that 95% of synchronization deviations were confined within 6 ms.

Data losses were identified using the per-sample index counter of the implant: any nonconsecutive index values indicated dropped samples and delineated missing data segments. In early software versions, the sample index counter embedded in the data stream was not retrieved; thus, data losses could not be monitored. Continuous index tracking and data-loss detection were implemented in later versions, starting from sub-monkeyc / ses-day48. Early datasets without index tracking still exhibited clear SEPs; therefore, only the SEP data derived from these sessions were included in the Technical Validation section. The publicly released dataset contains metadata specifying whether the implant sample indices were recorded and provides an auxiliary “mask” channel that marks the interpolated samples (linear interpolation was employed by default) used to reconstruct continuous data.

Three experimental paradigms were interfaced with the acquisition system through the digital I/O board. For SEP recordings, a constant-current stimulator (USE-200, Unique Medical, Japan) delivered controlled electrical pulses to the median nerve, while each stimulus trigger was concurrently sent as a digital pulse to the I/O board. During motor-related tasks, button-press responses were captured by custom hardware that converted press and release actions into digital signals, which were digitized via the same I/O board for the subsequent behavioural timing analysis. For auditory stimulus presentation purposes, the sound stimuli were produced by a DATAPixx3 device (VPixx Technologies, Canada), along with digital timing pulses synchronized with sound onset. These pulses were recorded through the same I/O board.

Experimental Protocol

Resting-State and impedance measurements

Routine impedance and resting-state recordings were conducted twice weekly. The impedance was measured by applying a 240 µA current pulse to each electrode and recording the resulting voltage. The resting-state recordings captured 3-minute segments of baseline neural activity while the monkeys remained awake and were restrained to minimize movement.

Listening task

In this task, the monkeys passively listened to auditory stimuli while maintaining a stable posture. The listening task involved presenting auditory stimuli through speakers placed 1 metre in front of the monkeys. The stimuli consisted of C4 (Do), E4 (Mi), and G4 (So) notes arranged in four triads: DoMiSo, DoSoMi, MiDoSo, and SoMiDo. Each trial began 30 seconds after recording onset, with a 10-second intertrial interval (ITI). Each experimental session consisted of 40 trials and lasted approximately 7 minutes. The auditory sequences were pregenerated using MATLAB’s randperm function, and one of two predefined order files was used for each session. This paradigm was intentionally designed to enable the acquisition of neural recordings without additional training steps and to allow for the decoding of stimulus categories while minimizing motor and oculomotor confounders.

Pressing task

In the pressing task, which was conducted exclusively with Monkey C, the monkey voluntarily pressed one of two target buttons after receiving a start command from the experimenter. The monkey initially rested its right hand on a central home button. The start command was given only after the monkey had remained completely still for a sufficient duration. Upon being given the start command, the monkey was free to choose and press either the left or right button; the buttons were positioned asymmetrically at 100 mm and 150 mm from the home button, respectively.

Reaching task

The reaching task was conducted with both Monkey C and Monkey B. In this task, the monkeys rested one hand on the central home button, and the experimenter placed a piece of food 30 cm away from the button in a fixed position. The monkeys were instructed to reach for the food using the designated hand (left or right), alternating between hands across runs. As with the pressing task, the start command was given only after the monkey had remained completely still for a sufficient duration, ensuring that high-quality neural recordings free from motion artefacts were obtained. This task was designed to evaluate motor signals associated with left- and right-hand movements, ensuring balanced measurements across both hands.

Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SEPs)

Postoperatively, SEP recordings were used to assess cortical responses to median nerve stimulation. Electrical pulses were delivered via surface electrodes placed on the wrists (Fig. 2). Separate sessions were conducted for the left and right hands. The stimulation parameters included a frequency of 7 Hz, a pulse width of 0.2 ms, consistent with those used intraoperatively. The amplitude of the stimulation was adjusted according to two principles: ensuring a clear and observable neural response and minimizing the stimulation intensity to the lowest effective level. While many trials used an amplitude of 2.5 mA, the specific amplitude varied depending on the observed response. Trial-averaged responses were analysed to evaluate the consistency and stability of the SEP signals over time. SEP sessions occurred approximately once per month and provided a longitudinal functional validation of electrode placement.

Schematic illustration of the placement of the surface electrode for conducting median nerve stimulation at the left wrist. Electrical stimulation was delivered via a fixed bipolar surface electrode (with an interelectrode distance of 23 mm) placed over the course of the median nerve at the wrist. The cathode (−, red) was positioned proximally and the anode (+, black) was positioned distally. The wrist orientation (R ↔ U) indicates the radial (R) and ulnar (U) sides. The stimulation parameters were set to a 7-Hz frequency, a 0.2-ms pulse width, and an approximately 2.5-mA amplitude, adjusted to evoke a clear but comfortable motor response (thumb twitch).

Bipolar stimulation mapping

Bipolar cortical stimulation was employed postoperatively to functionally map the motor cortex and monitor the electrode performance over time.

During each mapping session (approximately every 2–3 months), stimulation was delivered through selected adjacent electrode pairs in a bipolar configuration using current-controlled, rectangular, biphasic, charge-balanced pulses (50 Hz, 300 µs per phase). The current began at 500 µA and gradually increased until visible movements were observed or until the safety limit was reached. The maximum current was maintained below 3 mA, corresponding to a charge density of ≤26 µC/cm2 (3 mA, 500 µs) and remaining within the manufacturer-specified safety range for repeated cortical stimulation. Each stimulation train lasted up to 2 seconds and was terminated immediately upon the detection of a motor response or any sign of discomfort. The monkey’s behaviour was continuously observed by the experimenter, and any visible movements were confirmed both in real time and by a subsequent video review.

To ensure the integrity of the behavioural and resting-state recordings included in the released dataset, no stimulation was performed during those sessions. Instead, these mapping sessions were scheduled independently, with at least a one-day washout period before subsequent recordings to minimize the level of interference while allowing for a longitudinal evaluation of the functional cortical engagement level. All stimulation events were logged in the metadata following the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) standard.

Animal welfare was carefully monitored throughout these awake stimulation mapping sessions. The sessions were limited in duration, with breaks provided as needed to prevent fatigue, and the experimental environment was kept calm. The animals tolerated the procedure well and exhibited minimal signs of stress or avoidance behaviour.

Preprocessing and BIDS conversion

The raw data acquired from the wireless ECoG device were initially saved in proprietary.bin/.hdr formats and converted to standard EDF files using the open-source Python library pyEDFlib (version 0.1.36). A semiautomated procedure was used to filter out invalid recordings, match them with task annotations, and generate event markers. During conversion to the BIDS standard, missing samples were linearly interpolated, and all interpolated points were flagged within a dedicated mask channel to facilitate exclusion in downstream analyses. The resulting datasets followed the BIDS specification for intracranial EEG (iEEG), with metadata and validation reports produced to ensure structural consistency.

Data Records

The dataset is publicly available on OpenNeuro, under the accession number ds006890 (https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds006890)14. All the data associated with this work are shared in a Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) standard. The dataset comprises data for two nonhuman primates (“monkeyc” and “monkeyb”), each with multiple recording sessions spanning the postoperative period. The folder hierarchy is as follows:

<dataset root>/

Within each subject’s folder (sub-monkeyb and sub-monkeyc), the data are organized into session-level directories labelled with the corresponding postoperative days (e.g., ses-day05 or ses-day06), reflecting the chronological sequence of recordings.

Each session directory contains an ieeg/ subfolder with all intracranial electrophysiology files and the relevant metadata. The *_ieeg.edf file stores continuous ECoG signals in the European Data Format obtained at a sampling rate of 1 kHz. Where applicable, an additional “interpolation mask” channel indicates which samples have been reconstructed during postprocessing. The *_events.tsv file is a tab-delimited file listing the onset times and descriptions of recorded experimental events (e.g., task cues and stimulus onsets). The *_channels.tsv file is a tab-delimited file describing each channel’s type (e.g., ECoG vs. TRIGGER), sampling frequency, status (e.g., “good” or “bad”), and any pertinent notes (e.g., “Used as software reference” or “Interpolation mask channel”). The *_ieeg.json file contains session-level metadata (sampling frequency, hardware setup, reference scheme, any applied filters), conforming to BIDS iEEG extension guidelines. The *_scans.tsv file lists all iEEG data files for the session, including acquisition timestamps.

The top-level file dataset_description.json summarizes the dataset’s title, authors, and BIDS version, and participants.tsv provides basic animal information (e.g., subject IDs, species). Additional optional files (such as impedance measurements or electrode coordinate metadata) may be given if relevant to particular sessions.

Data records are referenced via the repository’s assigned DOI, allowing users to download and explore the sessions of interest. No extensive summary statistics are provided here, as the dataset is intended for further inspection and analysis via standard neurophysiological or statistical methods. Researchers seeking specific signals (e.g., particular tasks or channel subsets) can navigate through the ses-dayXX folders to locate the corresponding *_ieeg.edf and associated metadata.

Technical Validation

Overview of the dataset

To provide a comprehensive overview of the dataset, we include a summary of the experimental sessions, task distributions, trial structure, and missing data characteristics. The dataset comprises multiple tasks—listening, pressing, reaching, and SEPs—collected across numerous sessions for Monkey B and Monkey C. For each task, we computed the numbers of sessions and runs, the relative frequency of the sessions, and the average number of trials per run. An overview of these statistics is presented in Table 1, and a detailed version is provided in the released dataset14 under derivatives/summary/.

To assess the extent and nature of the data loss, we performed a subject-level quality control analysis. For each run, we calculated the number and proportion of missing samples, with the results compiled in subject-specific quality control tables located in derivatives/qc/. Overall, Monkey B had an average missing data rate of 0.60% ± 0.55%, with brief data loss events averaging 1.84 ± 0.27 samples and valid contiguous segments averaging 398 ± 157 samples. The percentage of missing segments for Monkey C was 0.85% ± 0.46%, with similarly short missing segments (1.93 ± 0.28 samples) and an average valid segment length of 263 ± 87 samples. These results indicate that the amount of missing data was minimal and sparsely distributed within individual runs. All missing periods were explicitly annotated in the mask channel to support downstream quality control or preprocessing efforts.

Impedance stability

To assess the long-term stability of the subdural ECoG electrodes, we conducted regular impedance measurements throughout the study. Figure 3 shows how the overall impedance values evolved over time for each monkey, with the mean impedance (black trace) and the corresponding variability (grey-shaded region) plotted against the number of days post implantation. Both Monkey C (Fig. 3a) and Monkey B (Fig. 3b) exhibited stable impedance profiles, remaining well within the acceptable range (≲3 kΩ). Overall, these measurements confirm that the electrodes retained reliable performance over hundreds of days postsurgery, supporting the viability of continuous ECoG recording for the extended research protocols described here.

Time series of electrode impedance measurements in (a) Monkey C and (b) Monkey B. The black lines represent the mean impedance across all functional electrodes, and the grey shaded area indicates the confidence intervals (CIs). The vertical red dashed lines indicate the days on which functional mapping was performed. Both animals maintained stable impedance values throughout the recording period, suggesting reliable long-term electrode‒tissue contact.

Band power analysis

We performed a power spectral analysis on the resting‐state ECoG signals to verify the stability of the neural band power over the long term. For each session, a 100‐second segment was selected from the middle of the 3‐minute recording to avoid initial transients and movement artefacts. The power spectral density (PSD) was then computed via MATLAB’s pwelch function with a 4,096‐point Hamming window. As shown in Fig. 3, both Monkey C (Fig. 4a) and Monkey B (Fig. 4b) demonstrated relatively consistent spectral features across hundreds of days postimplantation. The top row shows the average PSD curves, with vertical dashed lines delineating the five frequency bands (theta, alpha, beta, low‐gamma, and high‐gamma). The subsequent rows illustrate the time series of the mean band power (black traces) and the CI (grey shading). Despite minor fluctuations, no marked drifts or sudden decreases in band‐specific power were observed, indicating stable electrode functionality and the long‐term reliability of the recorded ECoG signals.

Resting-state spectral analysis of Monkey C (a) and Monkey B (b). The top row shows the average power spectral density (PSD) derived from a 100-second segment in each session. The remaining rows plot the session-by-session changes in the mean power (black lines) within each band, with the grey-shaded areas representing CIs across channels.

Motor task validation

To verify that motor‐related neural oscillations remained robust over the long term, we analysed the reaching‐task ECoG signals in both monkeys via event‐related spectral perturbation (ERSP) using EEGLAB’s newtimef function. Each trial was time‐locked from 500 ms before to 500 ms after movement onset and then averaged across all trials for each session. Figure 5 shows representative results: (i) time-frequency maps for the black-circled electrical channel in the corresponding row 4 (row 1), (ii) z‐scored waveforms of the same channel (row 2), (iii) session‐by‐session high‐gamma power across all channels (row 3), and (iv) the topographic distribution of high‐gamma power (row 4). Panels (a, b) represent left‐hand and right‐hand movements, respectively, in Monkey C; panels (c, d) show the corresponding data for Monkey B. The consistent elevation in high‐gamma (~60–90 Hz) following movement onset, along with clear topographical clustering over sensorimotor electrodes, supports the reliability of the implanted arrays for capturing voluntary motor activity. Across sessions, we observed no systematic decay in movement‐related spectral power, confirming electrode stability and data integrity.

Event-related spectral perturbation (ERSP) in reaching tasks for the two monkeys (Monkey C: a,b; Monkey B: c,d). For each subpanel pair, the first row shows the session-averaged time–frequency map of a representative channel, aligned to movement onset (vertical red line); the second row displays the z-score time course of the same channel. The horizontal red line shows the baseline period, and the purple line shows the analysed period in rows 3 and 4. The third row plots session-by-session mean high-gamma (~60–90 Hz) ERSP (solid lines) with confidence-interval shading. The fourth row presents the topographic distributions of high-gamma ERSP, shown in the same spatial orientation as the atlas-based array layout in Fig. 1c. The black-outlined electrodes indicate the task-relevant sites identified through anatomical localization, and the red-outlined electrode corresponds to the exemplar channel displayed in the first row. Left-hand movements are shown in (a,c), and right-hand movements are shown in (b,d).

Figure 6 shows representative spectral and temporal patterns derived from the pressing task performed exclusively by Monkey C. Panel (a) presents the trial‐averaged signal from the red-circled channel in panel (c), which is shown both as a z‐scored waveform (left) and a time‒frequency representation (right). Panel (b) depicts the session‐by‐session changes in event-related changes in beta (13–30 Hz; left) and high‐gamma (60–90 Hz; right) power, and panel (c) shows topographic maps of the session-averaged corresponding power.

Event-related spectral perturbation (ERSP) in pressing tasks for Monkey C. (a) Z scored time-domain signal (left) and time‒frequency map (right) for a single representative electrode, averaged across all pressing trials and aligned with the onset of movement (time = 0; red vertical line). (b) Session-wise mean beta-band (13–30 Hz, left) and high-gamma band (60–90 Hz, right) ERSPs, averaged across electrodes; shaded areas denoting the 95% confidence interval (CI) across electrodes. (c) Topographic distribution of the beta-band (left) and high-gamma band (right) ERSP changes relative to the baseline, averaged across recording sessions and expressed in decibels (dB). The orientation is as shown in Fig. 1c; black- and red-outlined electrodes denote task-relevant and exemplar channels, respectively. (d) Topographic distribution of the –log₁₀(p) values derived from Spearman’s rank correlation between the daily mean beta-band (left) or high-gamma band ERSP (right) and the daily mean movement speed. The black-circled electrodes indicate task-relevant sites.

To assess the functional validity of the motor features, the movement speed in the pressing task was computed per trial as the rest-to-response distance divided by the movement time (from the release of the home button to the responding of response button). For each recording day, we calculated the daily mean high-gamma ERSP for each ECoG channel and the daily mean speed. We then correlated the daily mean high-gamma ERSP with the daily mean speed across days using Spearman’s ρ for each channel and controlled for multiple comparisons across the channels with Benjamini–Hochberg FDR (q = 0.05). The results revealed that three channels over the sensorimotor cortex exhibited significant positive brain–behaviour associations (minimum significant ρ = 0.451, n = 45; FDR-corrected p < 0.02; Fig. 6d). These findings indicate that the high-gamma-band ERSPs are associated with the faster movement execution.

Listening task validation

We further investigated how the ECoG signals captured discrete auditory features by delivering triads of musical notes (e.g., C4, E4, and G4) in rapid succession. In the trial‐averaged waveform (Fig. 7, top row), three distinct peaks emerged, closely aligning with the timing of the three consecutive notes. A corresponding time‒frequency representation (second row) revealed momentary power surges in the low-frequency range around each note onset. These results suggest that ECoG recordings can reliably track rapid multisyllabic (or multitone) auditory events.

ECoG responses to triad stimuli for Monkey C (panel a) and Monkey B (panel b). The first row shows the trial-averaged ECoG waveforms from a representative electrode (marked as the red circle in the bottom row), with three distinct peaks corresponding to the three musical notes (the red vertical lines mark each onset). The horizontal red line shows the baseline period, and the purple line shows the analysed period in rows 3 and 4. The second row provides a time‒frequency map of the same electrode. The session-by-session evolution of alpha ERSP (third row) indicates minimal variance across extended experimental days, with grey shading indicating confidence intervals across channels. The bottom row depicts topographic maps of ERSP changes during triad presentation. The orientation is as shown in Fig. 1c; black- and red-outlined electrodes denote task-relevant and exemplar channels, respectively. The strongest responses are clustered along the lateral electrode sites, presumably near the temporal cortex.

Notably, when we analysed the session‐by‐session changes in the alpha band (Fig. 7, third row), we observed consistent low‐gamma responses over an extended period, with no significant attenuation across tens or hundreds of daily sessions. This finding supports the view that the implant stability was sufficient to detect subtle auditory‐evoked oscillations over time. In the topographic distributions (fourth row), electrodes near the lateral edge of the subdural grid exhibited the strongest power modulation. Given that these contacts likely reside closer to temporal auditory regions in the macaque brain, the spatial pattern aligns with our hypothesis that the device effectively records cortical activity associated with auditory processing.

SEP validation

We further examined the stability of ECoG recordings by measuring somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) in response to median nerve stimulation of the left or right hand in two monkeys. Figure 8 shows representative data for Monkey C (panels a,b) and Monkey B (panels c,d), demonstrating that a prominent peak occurred approximately 23 ms poststimulus, which is commonly attributed to early cortical responses in primary somatosensory areas. This peak, indicated by a black arrow, remained consistent in amplitude and latency across extended postimplantation intervals. Additionally, the spatial distribution of SEP magnitudes suggested stable electrode functionality in the regions most responsive to tactile input, as expected. When viewed over multiple recording days, the SEP waveforms and corresponding z scores did not exhibit systematic reduction or drift, reinforcing the notion that the tissue–electrode interfaces remained robust even after hundreds of days. Taken together, these findings indicated that our data captured rapid sensorimotor signals over a long timescale, providing further support for the long-term viability of the implanted ECoG arrays.

Long-term monitoring of neural potential and high-gamma power responses to median nerve stimulation. (a,b) represent Monkey C, and (c,d) show analogous data for Monkey B. In each panel, the top-left subpanel displays a trial-averaged SEP waveform (z scored) aligned to stimulus onset (red vertical line), with the red horizontal line showing the baseline period. The ~23 ms peak, indicated by a black arrow, is a hallmark of early cortical activation following median nerve stimulation. The bottom-left subpanel presents a topographic map of the SEP amplitude (of z scores) at that peak latency. The orientation is as shown in Fig. 1c; black- and red-outlined electrodes denote task-relevant and exemplar channels, respectively. On the right, a heatmap depicts the temporal evolution of the SEP peak response (z score) across multiple recording days (horizontal axis) for all channels (vertical axis). Warmer colours denote higher z scores, indicating stronger SEP amplitudes.

Usage Notes

All ECoG recordings are organized in the BIDS iEEG format for compatibility with popular neurophysiology toolkits14. The dataset files include standard BIDS files such as ‘*_events.tsv’ for alignment of time-locked events (e.g., stimuli and button presses), and ‘*_channels.tsv’ files which annotate channel types (ECoG vs. triggers), reference usages, and interpolation statues (if any).

Users who do not require a BIDS-based workflow may still read the ‘*_ieeg.edf’ files using generic EDF readers. In this case, we recommend referring to the ‘*_ieeg.json’ files for metadata (e.g., sampling frequency, software reference channel, filter settings) and to ‘*_channels.tsv’ for channel-specific details (bad or questionable channels, impedance measurements if available, etc.).

Additionally, some sessions include an “Interpolation Mask Channel,” typically labelled ‘Misc_InterpMask’ in ‘*_ieeg.edf’ and documented in ‘*_channels.tsv’. This channel (1 = interpolated, 0 = original) helps researchers identify segments of data that underwent gap filling due to transient recording dropouts or noise artefacts.

The 32-channel configuration provides bilateral sensorimotor and temporal coverage, enabling stable longitudinal recordings and supporting analyses of spectral and evoked dynamics as well as cross-task decoding. Although the implant supported stimulation, no stimulation trials were performed during the release period. Bipolar stimulation mappings were implemented separately with adequate washout intervals, ensuring that stimulation effects did not confound the spontaneous and task-evoked neural dynamics.

While the present dataset focuses on ECoG recordings derived from the sensorimotor and partial temporal cortices, its design and organization sheme enable broader applicability. These long-term, multitask recordings offer a rich framework for investigating cortical dynamics across diverse behavioural and sensory conditions. These characteristics make the dataset suitable for studies of both within-task and cross-task neural representations.

With respect to array localization, the electrode positions are atlas-based approximations rather than subject-specific postoperative reconstructions. Consequently, users should interpret the provided visualizations and any spatially derived metrics as illustrative. Precise subject-specific coordinates are planned for release in a future versioned update of the OpenNeuro dataset, contingent upon the progress of the study and ethical approval.

No specialized platform is required to visualize or analyse the data beyond standard BIDS-compatible pipelines. Community-developed scripts for event-aligned time‒frequency analysis, spectral decomposition, and decoding can be readily applied to these files. Where relevant, please cite this Data Descriptor and the associated DOI when publishing results that utilize this dataset.

Data availability

The dataset is available at https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds006890.

Code availability

The custom code used in this study is available on GitHub in two repositories: bids_converter repository (https://github.com/Nehilum/bids_converter, release v1.0.0, MIT License) for converting raw recordings to BIDS format, and bids-ecog-techval repository (https://github.com/Nehilum/bids-ecog-techval, release v1.0.0, MIT License) containing all the technical validation analysis code used in this manuscript.

References

Caldwell, D. J., Ojemann, J. G. & Rao, R. P. N. Direct electrical stimulation in electrocorticographic brain–computer interfaces: enabling technologies for input to cortex. Front. Neurosci. 13, 804, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00804 (2019).

Dubey, A. & Ray, S. Cortical electrocorticogram (ECoG) is a local signal. J. Neurosci. 39, 4299–4311, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2917-18.2019 (2019).

Volkova, K., Lebedev, M. A., Kaplan, A. & Ossadtchi, A. Decoding movement from electrocorticographic activity: a review. Front. Neuroinform. 13, 74, https://doi.org/10.3389/fninf.2019.00074 (2019).

Yanagisawa, T. et al. Electrocorticographic control of a prosthetic arm in paralyzed patients. Ann. Neurol. 71, 353–361, https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.22613 (2012).

Lee, A. T. et al. Modern intracranial electroencephalography for epilepsy localization with combined subdural grid and depth electrodes with low and improved hemorrhagic complication rates. J. Neurosurg. 138, 821–827, https://doi.org/10.3171/2022.5.JNS221118 (2023).

RaviPrakash, H. et al. Deep learning provides exceptional accuracy to ECoG-based functional language mapping for epilepsy surgery. Front. Neurosci. 14, 409, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00409 (2020).

Gkogkidis, C. A. et al. Closed-loop interaction with the cerebral cortex using a novel micro-ECoG-based implant: the impact of beta vs. gamma stimulation frequencies on cortico-cortical spectral responses. Brain-Comput. Interfaces 4, 214–224, https://doi.org/10.1080/2326263X.2017.1381829 (2017).

Romanelli, P. et al. A novel neural prosthesis providing long-term electrocorticography recording and cortical stimulation for epilepsy and brain–computer interface. J. Neurosurg. 130, 1166–1179, https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.10.JNS17400 (2019).

Chao, Z. C., Nagasaka, Y. & Fujii, N. Long-term asynchronous decoding of arm motion using electrocorticographic signals in monkeys. Front. Neuroeng. 3, 3, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneng.2010.00003 (2010).

Vansteensel, M. J. et al. Longevity of a brain–computer interface for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 619–626, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2314598 (2024).

Arain, A. M. et al. Long-term intracranial EEG lateralization of epileptogenicity in patients with confirmed or suspected bilateral mesial temporal lobe onsets during epilepsy surgical evaluation. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 41, 522–529, https://doi.org/10.1097/WNP.0000000000001028 (2024).

King-Stephens, D. et al. Lateralization of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with chronic ambulatory electrocorticography. Epilepsia 56, 959–967, https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13010 (2015).

Calabrese, E. et al. A diffusion tensor MRI atlas of the postmortem rhesus macaque brain. Neuroimage 117, 408–416, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.05.072 (2015).

Yang, H. et al. Longitudinal Multitask Wireless ECoG Data from Two Fully Implanted Macaca fuscata. OpenNeuro https://doi.org/10.18112/openneuro.ds006890.v1.0.0 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) Exploratory Research for Advanced Technology under grant number JPMJER1801, Japan Science and Technology Agency Moonshot R&D under grant number JPMJMS2012 (TY), Japan Science and Technology Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) under grant number JPMJCR18A5 (TY), and Japan Science and Technology AIP Acceleration Research under grant number JPMJCR24U2 (TY).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, H., Fukuma, R., Namima, T. et al. Longitudinal multitask wireless electrocorticography data from two fully implanted nonhuman primates. Sci Data 13, 63 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06359-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06359-w