Abstract

Neonatal Screening (NS) is a mandatory secondary prevention program established in the 1960s to detect rare genetic disorders in newborns. Early diagnosis through NS enables timely interventions, helping to prevent severe health complications. Despite its long-standing implementation, there remains a scarcity of publicly available datasets to support medical research and academic analysis. In this work, we present a comprehensive dataset containing blood samples and associated information from nearly a decade of Neonatal Screening in Lombardy. This dataset offers valuable insights for medical studies on genetic disorders, early diagnostics, and treatment efficacy. Additionally, it can support academic research in data-driven healthcare analysis and policy development. By making this dataset publicly available, we aim to enhance research opportunities in neonatal health and contribute to the improvement of early intervention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Neonatal metabolic screening is a cornerstone of preventive medicine across the world1, enabling early detection of rare but severe metabolic disorders since the 1960s. These disorders, if left undiagnosed, can result in significant morbidity or mortality, underscoring the necessity of accurate and timely screening methods2,3. The Neonatal Screening program in the Lombardy Region targets four groups of conditions: endocrine disorders (congenital hypothyroidism and congenital adrenal hyperplasia), cystic fibrosis, inherited metabolic disorders (NBS), and genetic neuromuscular diseases (such as spinal muscular atrophy). The screened diseases can be rare (affecting no more than one person in 2,000), congenital (present at birth), and often hereditary. In Italy, there are clear rules and indications to deal with the full process4, in particular, reference is made to the Ministry of Health Decree of 13 October 2016 (https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/dettaglioAtto?id=56764#articoli) that allows each region to work on it independently but in the same way. The process begins with collecting a few drops of blood from each baby in every hospitals of the region, usually between 48-72 hours after birth, in accordance with current national and international reference standards. Then the blood drops are stored on barcoded cards called Guthrie card5 (DBS), along with demographic and medical data submitted manually to the system. Samples and data are then sent to Buzzi Hospital in Milan for analysis using Genetic Screening Processor6 and Mass Spectrometry7. Further details about the Lombardy’s Neonatal Screening analysis procedure will be added in the methods section. Poor-quality samples are flagged for recollection, labeled as BIS (if the sample is the second) or Controllo (if the sample is to check the previous one). The Mayo Clinic’s neonatal screening software called Collaborative Labour Integrated Reports (CLIR) (https://clir.mayo.edu/Home/About)8 flags samples with a high probability of being positive to one or more diseases. Doctors review these cases and may request a second sample for further analysis, repeating the process and measuring different markers taking in consideration the diseases to check. Final diagnoses are based on weight-specific and disease specific cut-off values developed by doctors.

To our knowledge, no large public datasets on newborn screening currently exist. Having access to a large volume of real newborn screening data is crucial for facilitating information sharing between screening centers. This not only enables the comparison of biochemical marker concentration distributions across different populations but also allows for the evaluation of data collection quality and diagnostic assignment processes. In particular, thanks to the group of positive cases that have managed to be collected, it will be possible to test new automatic diagnosis assignment techniques. For this reason, the proposed dataset9 can be exploited in both the medical and academic fields. While the fact that the information it contains is real makes it possible to understand certain characteristics of the Lombardy population and the distribution of the concentration of particular biochemical markers, its size, the technical measurement errors it contains and the large number of missing values make it an excellent dataset with which to test different data cleaning techniques10. Nowadays many synthetic data are used for many health projects11 because of privacy issue or data availability and surely and certainly using them is a good way to curb such problems. However, depending on the generative model used to create them, one may encounter different technical difficulties and levels of realism12.

The proposed dataset contains many observations from those that are usually fed into the model supporting the diagnostic process. Originally, the extracted observations contain samples of 10 years (from september 2012 to december 2022). The dataset originally comprised 985,792 rows and 266 features. The majority of the columns (235) correspond to biochemical marker concentration measurements, while 17 are binary features. The remaining columns contain information about the modules, such as the city of residence, the mother’s ethnicity, and the time of sample collection. To ensure data quality and address potential errors, the dataset was processed, resulting in a reduced size. As explained in the methodology section, this involved the removal of several variables and observations. Additionally, thanks to the contributions of physicians, diagnoses from the years 2016-2021 were integrated into the dataset. During the observed period, 198 positive cases were recorded. However, not every disease included in the screening had at least one positive case; rather, these 198 cases correspond to only 29 different diseases (Table 1).

Methods

The Fig. 1 illustrates the data-collection process organized by Lombardy region. Dried blood spot (DBS) samples and associated data collected at hospitals across Lombardy are sent to the Neonatal Screening Laboratory of Buzzi Hospital (Milan). This section details the steps for data collection, laboratory analysis, and data preparation/cleaning.

Ethical Consideration

Informed consent was obtained from all participating mothers through a signed document at the time of delivery. Pursuant to Italian legislation (e.g., Article 8, paragraph 2, Law No. 132/2025), and in accordance with local governance, the general informed consent permits secondary use of data stripped of direct identifiers. There is no evidence of harm associated with the DBS collection procedure. All procedures comply with applicable privacy regulations and institutional policies. The study was approved by the Territorial Ethics Committee 1 of Lombardy (CET 4–2023, 12 July 2023).

Collection

Between 48 and 72 hours after birth, a few drops of capillary blood are obtained from the newborn’s heel (typically the right foot) and applied to a Guthrie card identified by a barcode. This time window balances neonatal physiological adaptation (reducing false-positive and false-negative results) with timely detection of target conditions such as congenital hypothyroidism and inborn errors of metabolism.

At the same time, a questionnaire records perinatal and maternal information. Anamnestic data are manually entered into the hospital information system by healthcare workers at each hospital, along with the associated barcode. Upon arrival at Buzzi Hospital, the barcode is scanned allowing the system to automatically retrieves the linked clinical/demographic information for analysis.

Shipping of Guthrie cards to Buzzi Hospital

In Lombardy, neonatal screening is centralized at Buzzi Hospital (Milan). Everyday hospitals send Guthrie cards in numbered parcels for processing. To ensure privacy, laboratory staff have defined two identifying variables that are excluded from the published dataset: one linked to the individual child and the other to the sample.

After associating the child’s name with the barcode on the corresponding card, the system automatically integrates additional information. Occasional clerical errors may occur during manual handling (e.g., loss or physical damage of cards).

DBS analysis at the “V. Buzzi” Children Hospital

The DBSs were processed using the Neobase newborn screening kit (PerkinElmer, Milan, Italy). Single 3.2 mm spots were punched using a DBS puncher (PerkinElmer, Italy) into 96-well plates. A total of 100 μL of the PerkinElmer extraction working solution was added to each well. The microplate was shaken for 45 min at 650 rpm at 45 ∘C and incubated for 120 min at room temperature to ensure the complete derivatization of the extracted succinylacetone. The plate was then quantified using a Waters TQD (Waters Corporation, Sesto San Giovanni, Italy) or Quattro Micro mass spectrometer in FIA-MS/MS. The concentrations were calculated by comparing the measured analyte intensities to those of the internal standards multiplied by the internal standard concentration and relative response factor. Eleven amino acids were analyzed: alanine (Ala), citrulline (Cit), arginine (Arg), glycine (Gly), leucine/isoleucine (Leu/lle/Pro-OH), methionine (Met), ornithine (Orn), phenylalanine (Phe), tyrosine (Tyr), and valine (Val). Thirty-one acylcarnitines were analyzed: C0, C2, C3, C3DC, C4, C4DC, C5, C5:1, C5DC, C5OH, C6, C6DC, C8, C8:1, C10, C10:1, C10:2, C12, C12:1, C14, C14:1, C14:2, C14OH, C16, C16:1, C16OH, C16:1, C18, C18:1, C18:2, C18OH, and C18:1OH13. The proposed dataset do not contain all of the cited biochemical entity. Calibration procedures are also taken into consideration for the analysis. In particular, each assay performed on the PerkinElmer GSP machine is calibrated using a specific calibration curve, while the mass spectrometer relies on internal standards for calibration.

Analysis of results and identification of positives

Initial post-analytical evaluation is performed using the interactive web tool called Collaborative Laboratory Integrated Reports (CLIR)8. It is a very sophisticated software that has mainly three goals:

-

Replacement of traditional cutoff values with continuous adjustments for age and other covariates of reference ranges shown as seamless percentile charts. CLIR reference ranges are derived by retrospective analysis of “big data”, tens and even hundreds of thousands of data points from a growing worldwide community of collaborators.

-

Creation of cumulative, covariate-adjusted disease ranges for all informative markers for target conditions, usually clustered by specialty and/or type of markers.

-

Post-analytical interpretive tools that integrate all relevant results into a single score. Tools are applicable either to the diagnosis and/or prognosis of a condition or to the differential diagnosis between pairs of conditions (for example benign variant vs. classic disease, responsive/not responsive to treatment).

The system automatically identifies babies with a high likelihood of having one or more target conditions. Laboratory physicians review the alerts and, when it is necessary, a repeat DBS is obtained for re-testing.

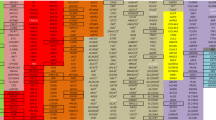

In the subsequent analysis, diagnosis is performed manually using conventional cut-off values, adjusted by four different weight categories (weight < 1500 g; 1500 g < weight < 2000 g; 2000 g < weight < 2500 g; weight > 2500 g) and three different sampling times (Figs. 3-6).

Data preparation

Data extraction from the database was performed by the hospital’s IT support team. Data preparation involved different scripts implemented in Python, primarily using the polars library.

Diagnostic information from 2016 to mid–2021 was integrated by merging a supplemental file via a unique identification code. The positive cases included 198 children diagnosed with 29 different metabolic diseases across various groups 1.

Many samples contained multiple consecutive values within the same cell for several numerical variables. As the second value could not be reliably identified or interpreted, only the first value was retained, rounded to two decimal places. Composite variables derived from other fiealds were removed to avoid redundancy. Two additional biochemical markers, s-TSH and s-17OHP, were excluded because they were measured in only 25 and 3 healthy newborns, respectively. Features judged unreliable, inconsistent or privacy-sensitive (Allele 1, City, Ethnicity, Sampling, AnswerIX, SampleQuality, id, and SampleBarCode) were removed. In particular, the removal of id and SampleBarCode ensured full anonymization of patient data.

All records were sorted by SamTimeCollected. Only the first observation for each patient ID was retained, except for affected children, for whom the diagnostic record was preserved, yielding 791,752 records.

After the feature reductions, the number of variables was 100. Consequently, data type were standardized. Since all binary variables indicate the presence or absence of a specific characteristic or condition, the high number of missing values resulted from many operators omitting negative responses, leaving the field empty. For this reason, missing values in binary variables were recoded as 0.

Handling of missing values is particularly critical, as “Ignoring or inadequately handling missing values can lead to biases and loss of statistical power”14. Despite this, we opted not to modify the large number of missing values in the dataset, even though proper handling is generally preferable to ignoring them15. This choice allows users to evaluate alternative strategies (Fig. 2)16,17,18,19,20.

Two potentially informative variables SamTimeReceived and SamTimeCollected, were frequently incomplete or incorrectly recorded. These variables would have been particularly valuable if timestamps were available for all observations, but they were missing for most observations. Consequently, only the calendar date was retained and variable names were updated accordingly.

We then computed the interval between SamTimeCollected and DateOfBirth and excluded all observations with this value lower than 1 or greater than 3 days. After this filtering step, the final number of rows was reduced to 748,716.

Outliers were retained to preserve the dataset’s Although several variables exhibited extreme values (including maxima exceeding three times the 99th percentile), the definition of outliers is context-dependent. We chose to retain all values as extracted from the hospital server in order to allow users to determine their own outlier definitions and apply appropriate correction methods as needed.

Data Records

The data are available on Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.164111499. The dataset is stored as a separate comma-separated values (CSV) file, where each record corresponds to the first sample collected from a newborn in Lombardy. It includes numeric, string, date, and binary columns.

The dataset consists of 748,716 rows and 100 columns. A complete list of feature names is provided in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 with the respective descriptive statistics.

Technical Validation

Developing datasets is a process that requires significant responsibility and attention. Data quality is of fundamental importance, as it has a major impact on the reliability of extracted information. It is essential to ensure that this medical dataset conforms to the recommendations outlined by the IEEE in the paper IEEE Recommended Practice for the Quality Management of Datasets for Medical Artificial Intelligence21.

This section outlines several procedures for verifying and inspecting data quality. The code file available in the repository includes checks to ensure the correctness of certain information. In particular:

-

The fact that all babies with the variable Premature equal to 1 have a GestationalAge lower than 36 was inspected and eventually corrected.

-

To select the first sample for each baby, the dataset was sorted taking in consideration the variable SamTimeCollected.

-

A check was made on the time window of sample acquisition by calculating the difference between date of collection and date of birth. Some observations were found to be far outside the 48-72 hour window of the health standard. In some cases the error is probably a typing error, while in others there may have been an unforeseen event that caused a delay. These samples, in case they did not belong to positive children, were removed from the published dataset.

-

Other features that didn’t deal with their original description were deleted.

There are also some medical shrewdness applied, in particular during the extraction of the biochemical markers concentrations like the periodic change of reagents and the daily sanitization of the spindle of PelkinElmer machine.

Data availability

The dataset is available on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16411149)9 while the Supplementary Information file is available on Github (https://github.com/G1oLo/NSE_Lombardy.git) in the Supplementary Information folder.

Code availability

The code was written in Python language (v. 3.12.4) using the polars (v. 1.8.2), numpy (v. 1.26.4), packages. The generation and validation code is available on GitHub at the following URL: https://github.com/G1oLo/NSE_Lombardy.git.

References

Bickel, H. et al. Neonatal mass screening for metabolic disorders: summary of recent sessions of the committee of experts to study inborn metabolic diseases, public health committee, council of europe. European Journal of Pediatrics 137, 133–139, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00441305 (1981).

Mütze, U. et al. Long-term outcomes of individuals with metabolic diseases identified through newborn screening. Pediatrics 146, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0444 (2020).

Oltman, S. P. et al. Newborn metabolic vulnerability profile identifies preterm infants at risk for mortality and morbidity. Pediatric research 89, 1405–1413, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01148-0 (2021).

Cassio, A. et al. The italian screening program for primary congenital hypothyroidism: actions to improve screening, diagnosis, follow-up, and surveillance. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 36, 195–203, https://doi.org/10.3275/8849 (2013).

Beyan, H. et al. Guthrie card methylomics identifies temporally stable epialleles that are present at birth in humans. Genome research 22, 2138–2145, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.134304.111 (2012).

Fingerhut, R. & Torresani, T. Evaluation of the genetic screening processor (gsp™) for newborn screening. Analytical Methods 5, 4769–4776, https://doi.org/10.1039/C3AY40593A (2013).

Glish, G. L. & Vachet, R. W. The basics of mass spectrometry in the twenty-first century. Nature reviews drug discovery 2, 140–150, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1011 (2003).

la Marca, G. et al. Current state and innovations in newborn screening: Continuing to do good and avoid harm. International Journal of Neonatal Screening https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns9010015 (2023).

Ospedale dei Bambini Vittore Buzzi Extended Lombardy’s Neonatal Screening Dataset. Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16411149 (2025).

Ridzuan, F. & Zainon, W. M. N. W. A review on data cleansing methods for big data. Procedia Computer Science 161, 731–738, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.11.177 (2019).

Kaabachi, B. et al. Can we trust synthetic data in medicine? a scoping review of privacy and utility metrics. medRxiv 2023–11, https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.28.23299124 (2023).

Lu, Y. et al. Machine learning for synthetic data generation: a review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.04062 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.04062 (2023).

Berardo, C. et al. Expanded Newborn Screening in Italy: The First Report of Lombardy Region. International Journal of Neonatal Screening 11, 31, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11020031 (2025).

Vesin, A. et al. Reporting and handling missing values in clinical studies in intensive care units. Intensive care medicine 39, 1396–1404, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-2949-1 (2013).

Janssen, K. J. et al. Missing covariate data in medical research: to impute is better than to ignore. Journal of clinical epidemiology 63, 721–727, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.12.008 (2010).

Guan, N. C. & Yusoff, M. S. B. Missing values in data analysis: ignore or impute? Education in Medicine Journal 3, https://doi.org/10.5959/eimj.3.1.2011.or1 (2011).

Cismondi, F. et al. Missing data in medical databases: Impute, delete or classify? Artificial intelligence in medicine 58, 63–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2013.01.003 (2013).

Zeng, D., Xie, D., Liu, R. & Li, X. Missing value imputation methods for tcm medical data and its effect in the classifier accuracy. In 2017 IEEE 19th International Conference on E-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom), 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1109/HealthCom.2017.8210844 (IEEE, 2017).

Cheng, C.-H., Chang, J.-R. & Huang, H.-H. A novel weighted distance threshold method for handling medical missing values. Computers in Biology and Medicine 122, 103824, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103824 (2020).

Afkanpour, M., Hosseinzadeh, E. & Tabesh, H. Identify the most appropriate imputation method for handling missing values in clinical structured datasets: a systematic review. BMC Medical Research Methodology 24, 188, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-024-02310-6 (2024).

Ieee recommended practice for the quality management of datasets for medical artificial intelligence. IEEE Std 2801-2022 1–31, https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEESTD.2022.9812564 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Neonatal Screening of Lombardy for the provision of data and Luca Marconi for his effort. The authors acknowledge funding support provided by PNRR funds (CUP: H41J24000400002) and Fastweb SpA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.L.: Responsible for cleaning the data, writing the paper and the figures and tables in it L.A.: Medical support for clarification of values of variables in the dataset and their meaning. C.C.: Responsible for data collection and extraction. Head of the Neonatal Screening Laboratory of Lombardy F.C.: Supervisor of data cleaning choices and reviewer of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lopiano, G., Alberti, L., Cereda, C. et al. Extended Lombardy’s Neonatal Screening Dataset. Sci Data 13, 80 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06389-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06389-4