Abstract

Hematophagy is essential for the survival and development of blood-feeding nematodes, including Haemonchus contortus (the barber’s pole worm) – a gastrointestinal nematode model for the study of anthelmintic resistance and drug discovery. Upon host ingestion, the infective larvae of this nematode transit to parasitic stage, then consume blood, contributing to the pathology of haemonchosis, a disease responsible for substantial economic losses. However, this process cannot be replicated in vitro without blood supplements. Therefore, despite genomic insights into developmental biology and anthelmintic resistance mechanisms, hematophagy remains poorly understood in this and other blood-feeding species. Here, we present a transcriptome dataset from the in vitro-cultured parasitic larvae of H. contortus exposed to 100 µM hemin chloride, 10% serum, and 10% defibrinated blood of host animals. A proteomic dataset for the in vitro-cultured larvae exposed to 10% serum is also available. These resources enable exploration of blood-component-specific transcriptomic reprogramming, hub gene-driven translational/metabolic modules, and molecular adaptations. This dataset also enables identification of genes critical for blood-feeding adaptation and parasitism, advancing therapeutic targets for intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Haemonchus contortus (commonly known as the barber’s pole worm) is a blood-feeding nematode and a gastrointestinal nematode model for the study of anthelmintic resistance and drug discovery1. Due to its rapid development of resistance to major anthelmintic classes commonly used in clinical (e.g., benzimidazoles, macrocyclic lactones, and imidazothiazoles/tetrahydropyrimidines), H. contortus poses a major challenge to livestock health, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions2. The lifecycle of H. contortus involves a free-living phase and a parasitic phase, transitioning from L3 to adult within the host. Adult worms inhabit the abomasum of small ruminants (e.g., sheep and goats), producing thousands of eggs per day into the faeces. In the environment, eggs hatch and develop through the first- and second-larval stages into the infective third-stage larvae (L3s), which exsheath in the host following ingestion and subsequently develop into blood-feeding fourth-stage larvae (L4s) and adults. Hematophagy (blood-feeding behaviour) provides essential nutrients (e.g., amino acids, heme/iron, and steroids/hormones) for H. contortus and mediates key host–parasite interactions that contribute to the pathology of haemonchosis, a disease responsible for substantial economic losses3.

Due to the obligate reliance on host blood, H. contortus represents an important model in understanding hematophagy of parasitic worms and identifying potential therapeutic targets4. For instance, most blood-feeding parasites lack a de novo heme synthesis pathway and rely on host-derived heme. In H. contortus, the heme responsive gene (hrg-1) ortholog has been characterized an essential gene in heme utilization and a target candidate5,6. However, the development transition from free-living infective stage to the blood-feeding parasitic stage cannot be achieved in vitro, unless provided with high-concentration host blood supplements7,8. Therefore, despite genomic insights into nematode biology and anthelmintic resistance mechanisms9,10,11,12,13,14, hematophagy remains poorly understood in H. contortus and related species.

Recent evidence has highlighted that host serum represents a physiologically relevant condition in H. contortus in vitro culturing system and drug screening platform. Host serum exposure stimulated a range of cytochrome P450 genes (e.g., daf-9 and members of cyp-14A) and nuclear hormone receptor genes (e.g., nhr-8, nhr-35, and nhr-173) in the treated larvae, and gene silencing of nhr-17 and nhr-105 resulted in reduced larval development and motility in vitro, respectively15,16. In addition, host serum supplementation can enhance larval development, motility and survival in vitro and improve drug screening accuracy8,17. Despite these advances, hematophagy remains poorly understood in this nematode parasite. Clearly, a better understanding of nematode adaptations to and mechanisms underlying blood-feeding parasitism is expected to uncover new therapeutic targets and strategies for interventions5,16,18,19. No existing datasets capture transcriptomic/proteomic responses of blood-feeding nematodes in response to host blood components (heme, serum, whole blood) under controlled in vitro conditions.

Our aim was to characterize transcriptomic and proteomic changes in H. contortus larvae exposed to host blood components in vitro, in order to provide molecular insights into parasite adaptation to blood-feeding within the host. We performed transcriptomic profiling of in vitro-cultured larvae (a mixture of activated infective L3s and parasitic L4s) exposed to one of four treatments: 100 µM haemin chloride, 10% serum from uninfected sheep, 10% defibrinated blood from uninfected sheep, each supplemented into Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) as the common base medium (Fig. 1)20.

Experimental design, sampling and data acquisition during in vitro culturing of Haemonchus contortus larvae. Schematic representation of the in vitro culture system, developmental transition from the free-living, infective stage (exsheathed L3, xL3) to the early parasitic, blood-feeding stage of H. contortus, sampling strategy, and transcriptomic/proteomic analyses. Infective third-stage larvae (xL3s) are obtained by exsheathment (0.15% sodium hypochlorite, 38 °C) and cultured for 72 h at 38 °C under 10% CO₂ in control medium or medium supplemented with 100 µM haemin chloride, 10% heat-inactivated sheep serum, or 10% heat-inactivated defibrinated sheep blood. Total RNA is extracted from cultured larvae for cDNA synthesis and subsequent Illumina RNA sequencing. Raw sequencing reads are processed by adapter trimming, quality filtering (FastQC), alignment to the H. contortus reference genome, and gene-level quantification. Differential gene transcription analysis is performed using DESeq2. Cultured larvae are also processed for protein isolation, digestion and LC-MA/MS analysis. Mass spectrometry data is processed using Proteome Discoverer and MaxQuant. Technical validations are performed via daily visual inspection of cultured larvae to confirm viability and sterility; box-plot analysis of log₂(FPKM + 1) values across libraries to assess data distribution and normalization; gene count thresholds (FPKM > 1) to evaluate transcriptome coverage; hierarchical clustering and t-SNE to confirm biological reproducibility and treatment-specific expression patterns; and differential gene expression analysis using volcano plots (|log₂FC| > 1, adjusted P < 0.05). These metrics confirm high data quality, low technical bias, and clear transcriptional responses suitable for integrative transcriptomic and proteomic analyses.

In addition, we also performed proteomic analysis of the in vitro-cultured larvae exposed to serum and DMEM culturing medium. Integration of transcriptomic and proteomic data revealed several genes with significantly upregulated mRNA levels but markedly reduced protein abundance in the serum-exposed infective larvae. This discrepancy between transcriptomic and proteomic changes may be attributed to tight post-transcriptional regulations, a phenomenon previously observed in H. contortus7, particularly during the developmental transition from the free-living to parasitic stages in vitro.

These datasets provide a key information on data generation and utility in understanding the transcriptional architectures of blood-feeding adaptation and parasitism in barber’s pole worm and underpins the modification of in vitro culturing system and downstream drug screening8,15,17. Further data mining, preferably integrated with data from multiple molecular levels, should support the identification of blood-responsive genes/proteins, cross-species comparisons (e.g., Caenorhabditis elegans), and in vitro screening platform optimization.

Methods

Ethics statement

H. contortus (ZJ strain) was maintained in Hu sheep under helminth-free conditions. The use of sheep in this study was approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Zhejiang University (permit no. ZJU20241015). Blood was collected from experimentally infected sheep by trained personnel in the Animal Hospital affiliated to the College of Animal Sciences, Zhejiang University. Handling of sheep was strictly followed the Guidelines for the Use of Experimental Animals of the People’s Republic of China.

Nematode collection and culture

Faecal samples were collected from infected sheep and processed for egg collection using a flotation method. Eggs were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and collected by centrifugation, evenly spread on 2% agar plates (2 g agar in 100 mL water, autoclaved 30 min at 121 °C) and supplemented with DMEM as a nutrient medium. Plates were then incubated at 28 °C for 7 days to allow development to the infective stage. The infective L3s were collected by washing the agar surface with PBS and pelleting at 5,000 × g for 2 min, washed three times in PBS, and stored at 10 °C until use within three months.

Blood, serum and haem treatments

Exsheathed and CO₂-activated L3s (xL3s) were prepared as previously described7,21. For the haem and blood treatment groups, three biological replicates of approximately 1 × 10⁴ xL3s each were incubated for 72 h at 38 °C under 10% CO₂ in: (i) 100 µM sterile haemin chloride (Haem treatment) or (ii) 10% heat-inactivated, defibrinated sheep whole blood (Blood treatment). These were each paired with three matched DMEM control replicates. For the serum treatment, two biological replicates of about 1 × 10⁴ xL3s were incubated under the same conditions in 10% sterile heat-inactivated sheep serum (Serum treatment), compared to four corresponding DMEM control replicates. Gibco Antibiotic-Antimycotic (10,000 U/mL penicillin, 10,000 µg/mL streptomycin, 25 µg/mL amphotericin B; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was included in all conditions to prevent bacterial and fungal contamination. At the end of incubation, each culture (containing both xL3s and early L4s) was pelleted at 600 × g, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80 °C for downstream transcriptomic and proteomic analyses.

RNA extraction and RNA-seq

Total RNA was extracted from each sample (1 × 10⁴ worms per sample) using TRIzol (Invitrogen), with biological replicate numbers consistent with the treatment design: three replicates for haem, whole blood, and their matched DMEM controls; two replicates for serum treatment; and four replicates for serum-matched DMEM controls and treated with TURBO DNase (Thermo Fisher). Poly(A)+ mRNA was enriched on Oligo(dT) magnetic beads, fragmented to ~300 bp, and reverse-transcribed to cDNA. Strand-specific libraries were constructed with the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina), and sequenced (150 nt paired-end) on NovaSeq 6000 and HiSeq 4000 instruments. Raw reads were adapter-trimmed and quality-filtered with Trimmomatic v0.3922, mapped to the MHco3 ISE genome12 and reference gene models using RSEM23, and normalized to counts per gene. Differential expression was assessed using DESeq2 v3.11 with |log₂ fold change| > 1 and a P value < 0.0524, and these data were used for Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses of DEGs.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

To capture global transcriptional shifts beyond individual DEGs, we conducted GSEA on ranked gene lists using both KEGG and GO gene sets25. Pre-ranked lists were input into the clusterProfiler implementation of GSEA, with a false‐discovery‐rate cut-off of 0.25. This approach identifies coordinated pathway‐level changes even when single‐gene effects do not meet strict significance (|log₂ fold change| > 1 and a P value < 0.05).

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)

Co-expression networks were constructed with the WGCNA R package v1.7326. After removing duplicate entries and applying a log₂ transformation, the top 5,000 genes by median absolute deviation were retained. Sample outliers were excluded via hierarchical clustering. A soft‐thresholding power was chosen to approximate scale-free topology, and a signed adjacency matrix was built. Gene modules were then detected using the dynamic tree cut method. Module eigengenes (MEs) were correlated with treatment phenotypes. Genes with module membership (MM) > 0.95 and gene-trait correlation P < 0.01 were defined as hub candidates.

Co-expression network complex (CNC) construction and pathway analysis

Within each key module, genes were ranked by intramodular connectivity. The top 20 genes were designated hub genes. CNC networks were visualized in Cytoscape v3.10.227, and hub gene lists were subjected to GO enrichment to define their functional roles. This workflow enabled us to characterize the biological processes and molecular functions associated with highly connected genes in each co‐expression module under different treatment conditions.

Protein extraction, digestion, and mass spectrometry analysis

Proteins were extracted from three biological replicates of H. contortus larvae (1 × 10⁴ larvae per sample, three replicates per condition) following the protocol described21. Briefly, worm pellets were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and immediately thawed in a sonicator bath. This freeze–thaw cycle was repeated three times. Larvae were then homogenized by sonication (2 × 20 s cycles), and lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min to remove insoluble debris. For each sample, 50 μg of total protein was reduced with Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), alkylated with iodoacetamide, and digested with Lys-C/trypsin mix (Promega, USA). Peptide mixtures were acidified with 1.0% (v/v) formic acid and purified using Oasis HLB cartridges (Waters, USA). Purified peptides were analysed by LC-MS/MS using a QExactive Plus Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with a nano-electrospray ionization (nanoESI) source and coupled to an Ultimate 3000 RSLC nanoHPLC system (Dionex Ultimate 3000). Raw mass spectrometry data were processed and analysed using MaxQuant28 for peptide identification and quantification. Differentially expressed proteins were defined using a threshold of |log₂ fold change| > 1 and adjusted P value < 0.05.

Data Records

This project generated both transcriptomic and proteomic datasets characterizing H. contortus larval responses to distinct blood‐derived cues. The bulk RNA-seq component comprises 15 libraries prepared from xL3/early L4 larvae (about 1 × 10⁴ worms per replicate). The corresponding raw FASTQ files and a gene‐level count matrix have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession numbers SRP47342029 and SRP47804130. The 15 transcriptome libraries described here are identical to those used for the RNA-seq analyses presented in the manuscript, ensuring no additional batch effects were introduced. Proteomic samples were generated from the same batch of in vitro cultures, enabling integrative comparisons.

Proteomic data consist of six LC-MS/MS runs (serum vs. control, three replicates each) derived from the same larval pools. Raw instrument files along with MaxQuant search results and label‐free quantification tables are available via ProteomeXchange (PX) consortium under accession number IPX000759200031.

Processed transcriptomic and proteomic data files, including normalized expression matrices for each treatment and associated metadata tables, have been deposited in Figshare20.

Technical Validation

All experimental and analytical steps were designed to ensure data integrity, reproducibility, and suitability for downstream analyses (Fig. 1). First, H. contortus larval treatments and transfers were conducted under sterile conditions within a biosafety cabinet. Glassware and metal instruments were autoclaved, while plastic consumables were either pre-sterilized or disinfected with 70% ethanol. xL3/early L4 larvae were handled using sterile pipettes and transferred into prewarmed, antibiotic-supplemented DMEM for each treatment. Cultures were visually inspected daily during the 72 hours of incubation to confirm larval viability and absence of microbial contamination.

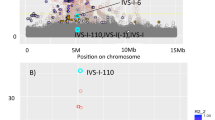

Box-plot analysis of log₂(FPKM + 1) values across all samples (Control, n = 3; Blood, n = 3; Haem, n = 3; Serum control, n = 4; Serum, n = 2) revealed tightly clustered medians (range: 2.1–2.3) and nearly identical interquartile ranges (IQR = 0.8–0.9) for each library (Fig. 2a). To assess sequencing depth and transcriptome coverage, we quantified genes per sample with FPKM > 1 (Fig. 2b). Each library detected 15,800–16,200 genes, with no systematic depletion in any treatment group. A single serum control replicate exhibited a modest 1.5% reduction, but all other QC metrics remained within expected ranges, demonstrating consistent library complexity and uniform transcriptome representation.

Data validation of transcriptomic dataset. (a) Distribution of log₂(FPKM + 1) values across all libraries. Box plots show the median (horizontal line), interquartile range (IQR, box) and full range (whiskers) for each sample: Control (Con, n = 3), defibrinated whole blood (Blood, n = 3), haemin chloride (Haem, n = 3), Serum control (Con-S, n = 4) and Serum (n = 2). Outliers are plotted as individual points. Uniform medians and consistent IQRs confirm effective normalization and minimal technical bias. (b) Number of detected genes per sample (FPKM > 1). Bar heights indicate the count of genes with FPKM > 1 for each library, coloured by treatment group. Comparable gene counts (~15,800–16,200) across all samples demonstrate consistent sequencing depth and transcriptome coverage. (c) Heatmap of gene transcription across all libraries. Expression values, row Z-scores of log₂(FPKM + 1) are shown, with columns representing samples (annotated by treatment in the top colour bar) and rows representing genes clustered by similarity. The colour scale denotes low to high expression. Clear co-clustering of biological replicates and distinct separation of treatment groups validate both replicate consistency and treatment-specific transcriptional programmes. (d) Two-dimensional t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (t-SNE) of transcriptomic samples. Each point corresponds to a library, coloured by experimental group. Distinct clusters for Con, Blood, Haem, Control-S and Serum illustrate the global dataset structure and confirm robust separation of treatment conditions.

Hierarchical clustering of the 100 most variable genes (row Z-scores of log₂[FPKM + 1]) yielded distinct sample clusters corresponding to each treatment (Fig. 2c). Biological replicates co-clustered without misassignment, and inter-group expression patterns were sharply delineated, confirming that blood-component-driven transcriptional programs, rather than technical artifacts, dominated the observed variation. This separation was further validated by t-SNE analysis, which resolved five discrete clusters matching the experimental groups (Fig. 2d). Uniform gene detection (15,800–16,200 genes at FPKM > 1) and tight treatment-specific clustering underscored the dataset’s biological reproducibility and the adequacy of sequencing depth to resolve expression differences.

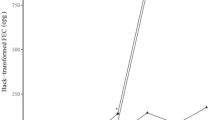

Volcano plots of fold changes between treated and untreated larvae (blood vs. control, serum vs. control, haem vs. control) were generated using thresholds of |log₂FC| > 1 and P < 0.05 (Fig. 3a–c). Pairwise functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) further supported their physiological relevance (Fig. 3e–f).

Distinct transcriptional alterations in Haemonchus contortus larvae exposed to host blood components. Volcano plots of differential gene expression (log₂fold change and –log₁₀ adjusted P value) for (a) blood treatment vs. control, (b) serum treatment vs. control, and (c) haem treatment vs. control. Blue and red points denote transcripts meeting significance thresholds (|log₂FC| > 1, adjusted P < 0.05) as down- and up-regulation respectively; grey points are non-significant. Circular KEGG pathway maps for the three comparisons: (d) blood vs. control, (e) serum vs. control, and (f) haem vs. control. Concentric rings represent the three KEGG hierarchy levels (categories, subcategories, individual pathways), and coloured arcs radiating outwards depict the direction and relative magnitude of pathway-associated gene regulation (blue indicates down, red indicates up, and grey indicates not significant).

Furthermore, WGCNA and CNC identified three major transcriptional modules associated with blood-, serum-, and haem-treated larvae (Fig. 4a). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed distinct functional signatures for each module (Fig. 4b), reinforcing the biological coherence of the observed transcriptional changes.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis of transcriptomes of Haemonchus contortus larvae exposed to host blood components. (a) Module–trait associations. Heatmap displaying Pearson correlation coefficients (upper triangle) and their statistical significance (P-values, lower triangle, in parentheses) between module eigengenes (rows) and experimental treatments (columns). Bar length represents gene ratio (numerical values indicated), with pathway colours corresponding to their respective modules. (b) Functional enrichment of co-expressed gene clusters. The top ten most enriched KEGG pathways per cluster are shown, ranked by gene ratio (proportion of cluster genes associated with each pathway).

Importantly, the 15 transcriptome libraries described here are identical to those used in the RNA-seq analyses, ensuring no additional batch effects. The proteomic samples were generated from the same larval culture batches used for transcriptome profiling, thereby minimizing variability between datasets and enabling integrative comparisons. This design ensures consistency across transcriptomic and proteomic datasets, reducing the likelihood of confounding batch effects.

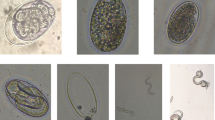

An important consideration is that the samples contained a mixture of xL3 and early L4 larvae. Based on microscopic inspection, approximately 1/3 of larvae developed to L4 by day 3 under serum treatment. While the L3/L4 ratio was broadly comparable across treatments, this developmental heterogeneity may still confound treatment-specific transcriptional responses. Users of this dataset should take this factor into account when interpreting results.

Another limitation is that only two biological replicates were available for the serum treatment group, due to constraints in parasite availability during the experiment. Although this falls below the commonly recommended minimum of three replicates for RNA-seq studies, quality control analyses (t-SNE clustering, Fig. 2d, and sample-to-sample correlation) showed that the two replicates were highly consistent, supporting their reproducibility. Nevertheless, users should be aware that statistical power for differential expression analysis is reduced in the serum group, and future work should aim to include at least three replicates to strengthen robustness.

Collectively, these analyses demonstrate that our RNA-seq data exhibit high technical quality, strong intra-group consistency, and well-defined inter-group transcriptional signatures. This robust dataset provides a reliable foundation for downstream differential expression, pathway, and integrated proteomic studies.

Data availability

All sequencing and proteomic data generated in this study are publicly available as follows: RNA-seq / transcriptome data are deposited in NCBI GEO / SRA under accession numbers SRP47342029 and SRP47804130 (including raw FASTQ files). Proteomic data (LC-MS/MS raw files, MaxQuant output, label-free quantification tables) are available via the ProteomeXchange Consortium under accession IPX000759200031. Processed data files and metadata are available in Figshare20 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29442299). All custom scripts, data processing pipelines, and analysis code are accessible on GitHub at https://github.com/zdduchina/ko-pathwaytree.

Code availability

All scripts used for data processing, differential expression analysis, GSEA, and WGCNA are available in our GitHub repository at [https://github.com/zdduchina/ko-pathwaytree]. Detailed documentation is provided to ensure reproducibility.

All scripts, custom code and workflow definitions used for data processing, quality control and analysis are provided in a publicly accessible GitHub repository (https://github.com/zdduchina/ko-pathwaytree). This includes, for the RNA‐seq arm: adapter trimming with Trimmomatic, FastQC reports, read alignment and quantification via RSEM, differential expression analysis with DESeq2, GSEA implementation using clusterProfiler, and WGCNA network construction.

References

Gilleard, J. S. Haemonchus contortus as a paradigm and model to study anthelmintic drug resistance. Parasitology 140(12), 1506–1522, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182013001145 (2013).

Kotze, A. C. & Prichard, R. K. Anthelmintic resistance in Haemonchus contortus: History, mechanisms and diagnosis. Advances in Parasitology 93, 397–428, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apar.2016.02.012 (2016).

Wang, T. et al. The proteome and lipidome of extracellular vesicles from Haemonchus contortus to underpin explorations of host-parasite cross-talk. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24(13), 10955, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241310955 (2023).

Perner, J., Gasser, R. B., Oliveira, P. L. & Kopáček, P. Haem biology in metazoan parasites - ‘The bright side of haem. Trends in Parasitology 35(3), 213–225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2019.01.001 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. Haem transporter HRG-1 is essential in the barber’s pole worm and an intervention target candidate. PLoS Pathogens 19(1), e1011129, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1011129 (2023).

Tong, D. et al. The mrp-3 gene is involved in haem efflux and detoxification in a blood-feeding nematode. BMC Biology 22(1), 199, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-024-02001-0 (2024).

Ma, G. et al. Molecular alterations during larval development of Haemonchus contortus in vitro are under tight post-transcriptional control. International Journal for Parasitology 48(9-10), 763–772, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.03.008 (2018).

Liu, L. et al. In vitro culture of the parasitic stage larvae of hematophagous parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. International Journal for Parasitology 55(5), 263–271, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2025.01.007 (2025).

Laing, R. et al. J.A. The genome and transcriptome of Haemonchus contortus, a key model parasite for drug and vaccine discovery. Genome Biology 14(8), R88, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2013-14-8-r88 (2013).

Schwarz, E. M. et al. The genome and developmental transcriptome of the strongylid nematode Haemonchus contortus. Genome Biology 14(8), R89, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2013-14-8-r89 (2013).

Doyle, S. R. et al. Genomic and transcriptomic variation defines the chromosome-scale assembly of Haemonchus contortus, a model gastrointestinal worm. Communications Biology 3(1), 656, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01377-3 (2020).

Doyle, S. R. et al. Genomic landscape of drug response reveals mediators of anthelmintic resistance. Cell Reports 41(3), 111522, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111522 (2022).

Wit, J. et al. Genomic signatures of selection associated with benzimidazole drug treatments in Haemonchus contortus field populations. International Journal for Parasitology 52(10), 677–689, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2022.07.004 (2022).

Zheng, Y. et al. Chromosome-contiguous genome for the Haecon-5 strain of Haemonchus contortus reveals marked genetic variability and enables the discovery of essential gene candidates. International Journal for Parasitology 54(13), 705–715, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2024.08.003 (2024).

Du, Z. et al. Genome-wide RNA interference of the nhr gene family in barber’s pole worm identified members crucial for larval viability in vitro. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 122, 105609, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2024.105609 (2024).

Zhang, J., et al Experimental validation of RNA interference technologies for improved control of barber’s pole worm. Veterinary Research. In press (2025)

Thilakarathne, S. S. et al. Evaluation of serum supplementation on the development of Haemonchus contortus larvae in vitro and on compound screening results. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26(3), 1118, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26031118 (2025).

Bouchery, T. et al. A novel blood-feeding detoxification pathway in Nippostrongylus brasiliensis L3 reveals a potential checkpoint for arresting hookworm development. PLoS Pathogens 14(3), e1006931, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006931 (2018).

Adegnika, A. A. et al. HookVac Consortium. Safety and immunogenicity of co-administered hookworm vaccine candidates Na-GST-1 and Na-APR-1 in Gabonese adults: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, phase 1 dose-escalation trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 21(2), 275–285, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30288-7 (2021).

Du, Z. & Ma, G. In vitro transcriptome and proteome of Haemonchus contortus larvae exposed to host blood components. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29442299 (2025).

Ma, G. et al. Dafachronic acid promotes larval development in Haemonchus contortus by modulating dauer signalling and lipid metabolism. PLoS Pathogens 15(7), e1007960, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1007960 (2019).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 30(15), 2114–2120, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 (2014).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 323, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-323 (2011).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods 9(4), 357–359, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923 (2012).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102(43), 15545–15550, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0506580102 (2005).

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 559, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 (2008).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Research 13(11), 2498–2504, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1239303 (2003).

Prianichnikov, N. et al. MaxQuant Software for ion mobility enhanced shotgun proteomics. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 19(6), 1058–1069, https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.TIR119.001720 (2020).

Du, Z. & Ma, G. Transcriptomic datasets of in vitro cultured Haemonchus contortus larvae in response to sheep serum. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP473420 (2023).

Du, Z., Tong, D. & Ma, G. Transcriptomic datasets of in vitro cultured Haemonchus contortus larvae in response to sheep blood and haemin chloride. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP478041 (2023).

Du, Z. & Ma, G. The proteomic datasets of in vitro cultured Haemonchus contortus larvae in response to sheep serum. iProX https://www.iprox.cn/page/project.html?id=IPX0007592000 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor Adrian Streit from the Max Planck Institute for Biology Tübingen and Professor Aifang Du from the College of Animal Sciences, Zhejiang University, for their constructive comments during the drafting of this manuscript. We thank the staff of The Shared Management Platform for Large Instrument and The Experimental Teaching Centre, College of Animal Sciences, Zhejiang University. This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 32473050, 32172877, and 32002304) and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (no. LQ23C180006), and Hangzhou Chengxi Sci-tech innovation Corridor Management Committee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M. conceptualized and designed this work. Z.D. developed the scripts and performed formal analysis together with F.W. Z.D., F.W., and D.Z. conducted data curation, investigation, and validation. Visualization was performed by Z.D., F.W., H.L., and G.M. Methodology was developed by Y.Y. and G.M. Project administration was handled by Y.Y., G.M., and resources were provided by X.C., Y.Y., and G.M. G.M. supervised the research. Funding acquisition was secured by F.W. and G.M., who also funded this work. Z.D. drafted the original manuscript, and F.W., D.Z., D.T., and G.M. reviewed and edited it with input from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, Z., Wu, F., Lin, H. et al. In vitro transcriptome and proteome of Haemonchus contortus larvae exposed to host blood components. Sci Data 13, 85 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06395-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06395-6