Abstract

The taxonomy and evolution of the genus Pseudoxenodon have long been poorly studied, and the paucity of genomic data in Pseudoxenodon critically impedes robust phylogenetic reconstruction and evolutionary analyses. Here, we present a chromosome-level reference genome assembly for P. stejnegeri generated through integrating the PacBio HiFi sequencing, Illumina short-read sequencing and Hi-C scaffolding techniques. The final genome size is 1601.26 Mb, with a scaffold N50 of 203.68 Mb and 97.07% assembled sequences anchored onto 18 pseudo-chromosomes. The BUSCO assessment revealed 97.8% completeness. We predicted 21,678 protein-coding genes, of which 17,531 (80.87%) genes were functionally annotated. Approximately 908.04 Mb repeat sequences were detected, representing 56.71% of the assembled sequences. This high-quality chromosome-level genome provides a valuable genomic resource for future studies on phylogenetics, evolution, and genetics of the genus Pseudoxenodon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The genus Pseudoxenodon, characterized by the obliquely arranged scales on the anterior part of the dorsal body, is a group of snakes that are widely distributed across southern and southeastern Asia1. This genus consists of seven species including P. stejnegeri, P. macrops, P. karlschmidti, P. inornatus, P. jacobsonii, P. baramensis and P. bambusicola2. Despite their ecological importance and unique morphological adaptations, they have been poorly studied, especially in a phylogenetic context. Due to lack of sufficient molecular data, the taxonomic classification of the genus Pseudoxenodon has remained controversial within the herpetological community. Recently, high-throughput sequencing techniques have been used to uncover snake genomic information and inform studies of snake evolution and development3, adaptation4,5, venom6,7 and phylogeny8.

Previously, the inference of phylogenetic relationships of the genus Pseudoxenodon has been based mainly on mitochondrial genes9,10,11,12. Many studies have demonstrated conflicting phylogenetic signals and evolutionary histories between mitochondrial and nuclear genes13,14,15,16. Moreover, increasing studies have even indicated that nuclear genes may provide more robust phylogenetic resolution for closely related lineages17,18. In recent years, phylogenetic reconstruction based on whole genome has emerged as a powerful and reliable tool for deciphering biodiversity, ecology and evolution of organisms19,20,21,22,23. However, only one species of Pseudoxenodon has undergone genome sequencing and assembly using just short read sequencing technology8. These limited genetic resources severely hinder accurate determination of the evolutionary relationship of Pseudoxenodon and in-depth study on their evolutionary history.

In this study, we present the first chromosome-level genome assembly of P. stejnegeri based on PacBio sequencing, Hi-C sequencing and Illumina sequencing technologies. We have assembled a high-quality genome with size of 1601.26 Mb and scaffold N50 length of 203.68 Mb. In total, about 97.07% bases have been anchored onto 18 chromosomes. This genome assembly not only provides genomic data for P. stejnegeri to study genetic diversity and population genetics but also offers a valuable resource for Pseudoxenodon studies on phylogenetics, adaptive evolution and comparative genomics.

Materials & Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experimental procedures were in accordance with the Chinese Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics law (GB/T35892–2018), and approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Chengdu University.

Sample collection and DNA extraction

An adult female individual of P. stejnegeri (Fig. 1a) was collected from Ningbo City, Zhejiang Province, China in August 2023. Muscle tissue was used to extract genomic DNA for whole-genome sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted using QIAGEN Genomic Kits following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality and quantity of the total DNA were determined using a NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific) and Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen). The integrity of the DNA was further evaluated using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Additionally, seven transcriptomic samples (muscle, blood, heart, kidney, liver, lung and spleen) were collected from the same specimen for transcriptome sequencing. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) as instructed by the manufacturer.

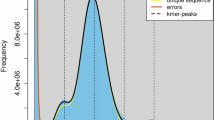

The morphological characteristics and genome information of P. stejnegeri. (a) Live specimen of P. stejnegeri. (b) The K-mer (K = 51) distribution for genome size estimation of P. stejnegeri genome. (c) The quality and length distribution of PacBio sequencing results. (d) Hi-C interaction heatmap of P. stejnegeri genome.

Library preparation and sequencing

For long-read sequencing, genomic DNA was used to construct PacBio SMRTbell library using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 3.0 with insert sizes of 15 kb. The size and concentration of library fragments were detected with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent technologies, USA). The qualified libraries were evenly loaded on SMRT Cell and sequenced using Sequel II platform (Pacific Biosciences, CA, USA) in CCS mode. For Illumina sequencing, a library with an insert size of 350 bp was constructed using the Truseq Nano DNA HT Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA). The Hi-C library was prepared using the Smartgenomics Hi-C kit (Smartgenomics Technology Institute, China). Initially, muscle tissue was fixed with 1% formaldehyde to cross-link DNA and proteins. The cross-linked DNA was then digested with Hind III restriction enzyme and the resulting overhangs were in-filled with biotinylated nucleotides. The resulting blunt ends were then ligated, and Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin (Life Technologies) was used to enrich the library for fragments containing biotinylated ligation junctions. Both Illumina standard genomic and Hi-C libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovoSeq 6000 platform with 2 × 150 bp reads. RNA-seq libraries were constructed using Hieff NGS Ultima Dual-mode RNA Library Prep Kit (Yeasen) and sequenced (2 × 150 bp) on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform.

Genome survey

The whole-genome survey analysis was performed using short reads from Illumina sequencing. The raw reads were first subjected to quality control using fastp v0.23.424 with default parameters which yielded 80.34 Gb clean data (Table S1). Based on these high-quality data, we used Jellyfish v2.3.125 to analyze the k-mer frequency distribution with a K value of 51 according to a previous study3. The k-mer distribution result was then imported to Genomescope v2.0 to predict genome size and heterozygosity. The genome size of P. stejnegeri was estimated to be approximately 1411.46 Mb, with a heterozygosity rate of around 0.61% (Fig. 1b).

Genome assembly

First, the PacBio sequencing data was filtered to remove low-quality polymerase reads using PacBio SMRT-Analysis software package. The reads with length < 50 bp, an average quality value < 0.8 and the reads containing self-ligated SMRTbell adapters were discarded to obtain high-quality polymerase reads. We employed ccs v4.2.0 in SMRTLink v9.0 with parameters --min-passes = 3 and --min-rq = 0.99 to process the remaining subreads to generate HiFi reads, resulting in 6,044,853 reads (107.33 Gb) with a read N50 of 17.7 kb (Fig. 1c, Table S2). Then, the HiFi long reads were assembled into contigs by using Hifiasm v0.19.926 with default parameters. The assembled contig-level genome comprises 660 contigs spanning 1,600,567,841 base pairs, with an N50 value of 94.32 Mb (Table 1).

To generate a chromosome-level genome, the raw Hi-C sequencing data was filtered using fastp v0.23.4 with default parameters, retaining 133.77 Gb clean reads (Table S3). These high-quality reads were subsequently mapped against the preliminary contigs by HiCUP v0.9.227 along with Bowtie v2.5.428. After Hi-C data alignment, we obtained about 219.40 million uniquely aligned valid reads, comprising 49.13% of the total reads (Table S4). Based on the valid reads, we applied ALLHiC v0.9.1429 to cluster, orientate, and order the contigs for scaffold-level assembly. Finally, we adopted Juicebox v2.2230 to manually fine-tune the assembly, resulting in a chromosome-level assembly. The assembled chromosome-level genome was 1.6 Gb, with 1.55 Gb (97.07%) anchored onto 18 pseudochromosomes and a scaffold N50 of 203.68 Mb (Figs. 1d, 2, 3, Table 1, S5). The assembled chromosomes were assigned names from chr1 to chr18 in descending order of length. We used subcommand telo in seqtk v1.5 (https://github.com/lh3/seqtk) to detect telomeric repeats in pseudochromosomes, and three pseudochromosomes achieved true telomere-to-telomere continuity (Table S6).

Circos plot for showing distribution of genomic features. The tracks from outermost to innermost are pseudo-chromosomes, tandem repeat density (maximum count: 11689), DNA transposon density (maximum count: 176), LINE density (maximum count: 1679), SINE density (maximum count: 53), LTR density (maximum count: 363), non-coding RNA density (maximum count: 235), protein-coding gene density (maximum count: 125), GC content and synteny among chromosomes.

Gene structure annotation

To obtain a high-quality gene annotation, three methods were used to predict protein-coding gene structure, including homology-based prediction, transcriptome-based prediction and ab initio prediction. For homology-based prediction, protein sequences of five species (including Pantherophis guttatus, Thamnophis sirtalis, T. elegans, Ahaetulla prasina, Mus musculus) were downloaded from NCBI database (Table S7). The protein sequences of each species were aligned to the assembled genome using genBlastA v1.0.431. The candidate homologous regions were provided as inputs to GeneWise v2.4.132 to precisely annotate gene structures. For transcriptome-based prediction, the raw RNA sequencing datasets were filtered using fastp v0.23.4, the retained clean reads were aligned to reference genome with Tophat v2.1.133. The alignment results were analyzed using Cufflinks v2.2.134 to perform genome-guided transcript assembly. For ab initio prediction, Augustus v3.5.035, geneid v1.4.536 and GENSCAN v1.037 were applied to annotate genes. The gene models derived from these different approaches were integrated using EVidenceModeler v2.1.038 to produce a non-redundant and complete gene set which was further corrected using PASA v2.5.339 to supplement the untranslated regions (UTRs) and alternative splicing information. Ultimately, we obtained a total of 21,579 protein-coding genes, with an average gene length of 28,275.09 bp, an average CDS length of 1,406.54 bp, and an average exon number of 8.31 (Fig. 4a, Table 2).

Gene functional annotation

The predicted protein-coding genes were aligned against the NCBI non-redundant (nr) database and Swiss-Prot40 database using DIAMOND v2.1.1141. Conserved domains, structural motifs and functional signatures were annotated using InterProScan v5.5942 to search against InterPro v91.043 database. We also employed eggNOG-mapper v2.1.844 together with eggNOG v5.0.245 database to predict gene functions through evolutionary homology analysis. Both InterProScan and eggNOG-mapper automatically performed gene ontology (GO46) assignment. In addition, we used pyfastx v2.2.047 to split protein sequence file into three smaller files which were then submitted to BlastKOALA v3.148 server for KEGG49 pathway identification. Overall, 17,531 (80.87%) predicted protein-coding genes were functionally annotated by at least one functional database (Fig. 4b, Table 3).

Repeat annotation

Repetitive elements in the P. stejnegeri genome were detected using a hybrid method that combined homology-based and de novo search strategies. We applied RepeatMasker v4.1.7 and RepeatProteinMask to carry out homology-based prediction with Repbase v23.0850 database and Dfam v3.851 database. For de novo prediction, LTR_Finder v1.0.752, Piler v1.053, RepeatScout v1.0.754 and RepeatModeler v2.0.655 were used to build a library of repetitive sequences. Consequently, RepeatMasker was utilized to predict transposable elements based on the library. Additionally, we identified tandem repeats from the P. stejnegeri genome using Krait v2.0.656 with pytrf v1.4.157 as search engine, maximum motif size of 100 bp, and minimum length of 10 bp. In total, we identified 9,976,736 repeat elements with total length of 908.04 Mb accounting for 56.71% of the assembled genome (Table 4).

Non-coding RNA identification

We initially employed Infernal v1.1.558 to align the assembled genome against Rfam v15.059 database for detecting non-coding RNAs (rRNAs, tRNAs, snRNAs, and miRNAs). Then, tRNAscan-SE v2.0.1260 with default parameters was used to explore tRNAs. Barrnap v0.9 (https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap) was used to predict ribosomal RNAs with the --kingdom parameter set to euk. Finally, we identified 3440 non-coding RNAs including 273 miRNAs, 1083 rRNAs, 1549 tRNAs and 342 snRNAs (Table 5).

Data Records

The raw PacBio, Hi-C, Illumina and RNA-seq data were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession number SRP64781861. We have also deposited the raw sequencing data in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA62) in National Genomics Data Center (NGDC63) with accession number CRA02513464 under BioProject PRJCA039323. The final genome and annotation data has been made available on the Figshare repository65. The final genome assembly has also been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession JBNIJY00000000066.

Technical Validation

We have used multiple methods to assess the quality of the genome assembly. First, the completeness of the genome assembly was evaluated using benchmarking universal single-copy orthologs (BUSCO) v5.6.067 based on vertebrata_odb10 lineage dataset and core eukaryotic genes mapping approach (CEGMA) v 2.568. The BUSCO result revealed 97.8% completeness (Fig. 2, Table S8), and 231 (93.15%) out of 248 core eukaryotic genes from CEGMA were identified in the assembled genome (Table S9). Then, we mapped Illumina filtered reads to the assembled genome using BWA v0.7.1869 for accurate assessment. The mapping result indicated that 99.71% paired-end reads could be aligned to the assembled genome (Table S10). We further assessed the quality value (QV) and k-mer completeness using Merqury v1.370 with 21-mers generated from Illumina short reads. The QV score and k-mer completeness were estimated as 47.1 and 89.91%, separately. We also performed chromosomal synteny analysis between P. stejnegeri and other two snakes (Ahaetulla prasina, T. elegans) with well assembled genomes using MCScanX v1.0.071. We observed a high degree of synteny among these species (Fig. 5). In conclusion, all these results illustrated that the assembled genome was a high-quality chromosome-level reference genome for P. stejnegeri.

Data availability

The assembled genome of P. stejnegeri can be downloaded from the NCBI GenBank at https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBNIJY000000000. The raw sequencing data, including Illumina, PacBio, Hi-C and transcriptome sequencing, can be publicly available from the NGDC GSA database at https://bigd.big.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA025134 and NCBI SRA database at https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP647818. The genome assembly, gene annotation and functional annotation can be obtained from Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28953233.

Code availability

No customized scripts were utilized in this study. All tools and pipelines were executed according to the manual and protocols of the published bioinformatic tools. The specific versions and parameters of software have been described in the Methods.

References

Zhang, B. & Huang, S. Relationship of old world Pseudoxenodon and new world Dipsadinae, with comments on underestimation of species diversity of Chinese Pseudoxenodon. Asian Herpetological Research 4, 155–165, https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1245.2013.000155 (2013).

Uetz, P. et al. The Reptile Database http://www.reptile-database.org (2025).

Peng, C. et al. Large-scale snake genome analyses provide insights into vertebrate development. Cell 186, 3519, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.06.021 (2023).

Ludington, A. J., Hammond, J. M., Breen, J., Deveson, I. W. & Sanders, K. L. New chromosome-scale genomes provide insights into marine adaptations of sea snakes (Hydrophis: Elapidae). BMC biology 21, 284, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-023-01772-2 (2023).

Li, J. T. et al. Comparative genomic investigation of high-elevation adaptation in ectothermic snakes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, 8406–8411, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1805348115 (2018).

Rao, W. Q. et al. The rise of genomics in snake venom research: recent advances and future perspectives. GigaScience 11, giac024, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giac024 (2022).

Almeida, D. D. et al. Tracking the recruitment and evolution of snake toxins using the evolutionary context provided by the Bothrops jararaca genome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118, e2015159118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2015159118 (2021).

Roberts, J. R. et al. Whole snake genomes from eighteen families of snakes (Serpentes: Caenophidia) and their applications to systematics. Journal of heredity 115, 487–497, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esae026 (2024).

He, D. The mitochondrial genome of the bamboo false cobra (Pseudoxenodon bambusicola). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 4, 1475–1476, https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2019.1574630 (2019).

Liao, J. et al. The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of big-eyed Mountain keelback Pseudoxenodon macrops. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 5, 736–737, https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2020.1715284 (2020).

Zong, H. et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of Pseudoxenodon macrops. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 5, 1473–1474, https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2020.1742222 (2020).

Zhang, L., Li, H., Wang, S. & Li, S. The complete mitochondrial genome of Pseudoxenodon stejnegeri (Squamata: Colubridae: Pseudoxenodontinae) and its phylogeny. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 5, 3734–3735, https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2020.1835584 (2020).

Gonçalves, H., Martínez-Solano, I., Ferrand, N. & García-París, M. Conflicting phylogenetic signal of nuclear vs mitochondrial DNA markers in midwife toads (Anura, Discoglossidae, Alytes): deep coalescence or ancestral hybridization? Mol Phylogenet Evol 44, 494–500, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2007.03.001 (2007).

Wallis, G. P. et al. Interspecific hybridization causes long-term phylogenetic discordance between nuclear and mitochondrial genomes in freshwater fishes. Molecular ecology 26, 3116–3127, https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14096 (2017).

Platt, R. N. et al. Conflicting Evolutionary Histories of the Mitochondrial and Nuclear Genomes in New World Myotis Bats. Systematic biology 67, 236–249, https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syx070 (2018).

Laine, V. N. et al. Whole-genome Analysis Reveals Contrasting Relationships Among Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genomes Between Three Sympatric Bat Species. Genome biology and evolution 15, evac175, https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evac175 (2023).

Near, T. J. & Keck, B. P. Free from mitochondrial DNA: Nuclear genes and the inference of species trees among closely related darter lineages (Teleostei: Percidae: Etheostomatinae). Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 66, 868–876, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2012.11.009 (2013).

Dool, S. E. et al. Nuclear introns outperform mitochondrial DNA in inter-specific phylogenetic reconstruction: Lessons from horseshoe bats (Rhinolophidae: Chiroptera). Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 97, 196–212, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2016.01.003 (2016).

Van Damme, K., Cornetti, L., Fields, P. D. & Ebert, D. Whole-Genome Phylogenetic Reconstruction as a Powerful Tool to Reveal Homoplasy and Ancient Rapid Radiation in Waterflea Evolution. Systematic biology 71, 777–787, https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syab094 (2022).

Muffato, M. et al. Reconstruction of hundreds of reference ancestral genomes across the eukaryotic kingdom. Nature ecology & evolution 7, 355–366, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01956-z (2023).

Coimbra, R. T. F. et al. Whole-genome analysis of giraffe supports four distinct species. Current biology 31, 2929–2938.e5, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.04.033 (2021).

Yu, D. et al. Whole-genome-based phylogenetic analyses provide new insights into the evolution of springtails (Hexapoda: Collembola). Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 200, 108169, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2024.108169 (2024).

Yang, W. F., Yu, Z. G. & Anh, V. Whole genome/proteome based phylogeny reconstruction for prokaryotes using higher order Markov model and chaos game representation. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 96, 102–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2015.12.011 (2016).

Chen, S. Ultrafast one-pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using fastp. iMeta 2, e107, https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.107 (2023).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 (2011).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature methods 18, 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021).

Wingett, S. et al. HiCUP: pipeline for mapping and processing Hi-C data. F1000Research 4, 1310, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.7334.1 (2015).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature methods 9, 357–359, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923 (2012).

Zhang, X., Zhang, S., Zhao, Q., Ming, R. & Tang, H. Assembly of allele-aware, chromosomal-scale autopolyploid genomes based on Hi-C data. Nature plants 5, 833–845, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0487-8 (2019).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox Provides a Visualization System for Hi-C Contact Maps with Unlimited Zoom. Cell systems 3, 99–101, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012 (2016).

She, R., Chu, J. S., Wang, K., Pei, J. & Chen, N. GenBlastA: enabling BLAST to identify homologous gene sequences. Genome research 19, 143–149, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.082081.108 (2009).

Birney, E., Clamp, M. & Durbin, R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome research 14, 988–995, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1865504 (2004).

Kim, D. et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome biology 14, R36, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36 (2013).

Trapnell, C. et al. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nature biotechnology 31, 46–53, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2450 (2013).

Keller, O., Kollmar, M., Stanke, M. & Waack, S. A novel hybrid gene prediction method employing protein multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 27, 757–763, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr010 (2011).

Alioto, T., Blanco, E., Parra, G. & Guigó, R. Using geneid to Identify Genes. Current protocols in bioinformatics 64, e56, https://doi.org/10.1002/cpbi.56 (2018).

Burge, C. & Karlin, S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. Journal of molecular biology 268, 78–94, https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1997.0951 (1997).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biology 9, R7, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7 (2008).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Research 31, 5654–5666, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkg770 (2003).

Boutet, E. et al. UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, the Manually Annotated Section of the UniProt KnowledgeBase: How to Use the Entry View. Methods in molecular biology 1374, 23–54, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-3167-5_2 (2016).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H. G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nature Methods 18, 366–368, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01101-x (2021).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031 (2014).

Blum, M. et al. InterPro: the protein sequence classification resource in 2025. Nucleic Acids Research 53, D444–D456, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae1082 (2025).

Cantalapiedra, C. P., Hernández-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P. & Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38, 5825–5829, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab293 (2021).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Research 47, D309–D314, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1085 (2019).

Gene Ontology Consortium et al. The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 224, iyad031, https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyad031 (2023).

Du, L. et al. Pyfastx: a robust Python package for fast random access to sequences from plain and gzipped FASTA/Q files. Briefings in Bioinformatics 22, bbaa368, https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbaa368 (2021).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. Journal of molecular biology 428, 726–731, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.006 (2016).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Research 53, D672–D677, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Bao, W., Kojima, K. K. & Kohany, O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mobile DNA 6, 11, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13100-015-0041-9 (2015).

Storer, J., Hubley, R., Rosen, J., Wheeler, T. J. & Smit, A. F. The Dfam community resource of transposable element families, sequence models, and genome annotations. Mobile DNA 12, 2, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13100-020-00230-y (2021).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Research 35, W265–W268, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm286 (2007).

Edgar, R. C. & Myers, E. W. PILER: identification and classification of genomic repeats. Bioinformatics 21, i152–i158, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1003 (2005).

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C. & Pevzner, P. A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, i351–i358, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018 (2005).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117, 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Du, L. et al. Krait2: a versatile software for microsatellite investigation, visualization and marker development. BMC Genomics 26, 72, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-025-11252-2 (2025).

Du, L. et al. Pytrf: a python package for finding tandem repeats from genomic sequences. BMC bioinformatics 26, 151, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-025-06168-3 (2025).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509 (2013).

Ontiveros-Palacios, N. et al. Rfam 15: RNA families database in 2025. Nucleic Acids Research 53, D258–D267, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae1023 (2025).

Chan, P. P., Lin, B. Y., Mak, A. J. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Research 49, 9077–9096, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab688 (2021).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP647818 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. GSA: Genome Sequence Archive. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 15, 14–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2017.01.001 (2017).

CNCB-NGDC Members and Partners. Database Resources of the National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation in 2025. Nucleic Acids Research 53, D30–D44, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae978 (2025).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA025134 (2025).

High-quality chromosome-level genome assembly of the snake Pseudoxenodon stejnegeri (Squamata: Colubridae). Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28953233 (2025).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBNIJY000000000 (2025).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: Assessing Genomic Data Quality and Beyond. Current Protocols 1, e323, https://doi.org/10.1002/cpz1.323 (2021).

Parra, G., Bradnam, K. & Korf, I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics 23, 1061–1067, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071 (2007).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome biology 21(1), 245, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Detection of colinear blocks and synteny and evolutionary analyses based on utilization of MCScanX. Nature Protocols 19, 2206–2229, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-024-00968-2 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200525, 32370486) and the second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (2024QZKK0200). We would also like to thank Zihao Yang in Shenzhen Bughug Cultural Technology Co., Ltd for his kindly helps in sample collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lianming Du and Peng Guo designed this study; Qin Liu, Songwen Tan and Peng Guo dissected and collected the samples. Jiahao Chen and Qin Liu extracted DNA and RNA. Lianming Du, Jiahao Chen and Qin Liu performed data analysis. Lianming Du wrote the paper. Peng Guo revised the paper. All authors had read, revised, and finally agreed to submit this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, L., Chen, J., Liu, Q. et al. High-quality chromosome-level genome assembly of the snake Pseudoxenodon stejnegeri (Squamata: Colubridae). Sci Data 13, 93 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06405-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06405-7