Abstract

Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax, a perennial herb belonging to the Caryophyllaceae family, demonstrates substantial pharmacological value and serves as an ideal model system for studying chasmogamous and cleistogamous (CH-CL) floral dimorphism. In this study, by integrating short-read, PacBio HiFi, Hi-C, and transcriptome sequencing data, we generated a high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly for P. heterophylla. The 2.19 Gb genome exhibits high continuity (scaffold N50 = 144.78 Mb) and completeness (97.83% BUSCO score), with 99.36% sequences anchored to 16 pseudo-chromosomes. Repeat elements constituted 79.41% of the assembled genome, with long terminal repeats accounting for 67.30%. The analysis identified 37,158 protein-coding genes, of which 87.19% (32,397) received functional annotations. This high-quality genome assembly establishes a pivotal foundation for uncovering the genetic mechanisms underlying CH-CL floral differentiation and bioactive compound biosynthesis, while supporting molecular breeding initiatives for this pharmacologically valuable species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax, a perennial herb from the Caryophyllaceae family, is a renowned medicinal plant in traditional Chinese medicine1,2. With a therapeutic history spanning centuries, it was first officially documented in a Qing Dynasty pharmacopeia, Ben Cao Cong Xin (1757)1. This species thrives in mountain valleys and moist shaded forests, predominantly across northeastern and eastern China, including the provinces of Liaoning, Shandong, Fujian, Guizhou, and Anhui (https://www.iplant.cn/info/Pseudostellaria%20heterophylla). Its dried tuberous root, termed Radix Pseudostellariae, serves as the primary medicinal material, exhibiting pharmacological properties including body fluid replenishment, enhancement of splenic and pulmonary functions, and maintenance of physiological homeostasis. In clinical practice, it has been traditionally prescribed to alleviate fatigue, anorexia, post-illness asthenia, and chronic dry cough3,4,5,6. Due to its mild therapeutic properties, it is commonly used in pediatric applications as a ginseng substitute, earning its Chinese vernacular name hai-er-shen (literally Child’s Ginseng)1.

Modern pharmacological studies have identified various bioactive compounds from P. heterophylla, including cyclic peptides, polysaccharides, saponins, and amino acids1,7. Among these, cyclic peptides, especially heterophyllin B (HB), are the characteristic constituents with significant pharmacological effects such as anti-inflammatory, antitumor, immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and anti-aging activities, as well as cognitive enhancement2,8,9,10,11. Recent studies have shown that cyclic peptides are ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides. The precursor linear peptide of HB is initially encoded by the PhPreHB gene, and subsequently undergoes enzyme-catalyzed macrocyclization, primarily mediated by the peptide cyclase PhPEPTIDE CYCLASE3 (PhPCY3) to generate the mature HB12,13. However, a comprehensive understanding of the biosynthetic pathway and its regulatory mechanisms of cyclic peptides in P. heterophylla remains elusive.

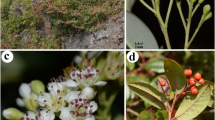

In addition to its medicinal value, P. heterophylla is also well-known for typical chasmogamous-cleistogamous (CH-CL) mixed breeding system of significant evolutionary importance14,15,16. This dimorphic species produces both open (chasmogamous, CH) flowers and closed (cleistogamous, CL) flowers on the same individual (Fig. 1a). The CH flowers display a complete floral structure with five sepals, five petals, ten stamens, and three carpels, adapted for pollinator attraction and outcrossing (Fig. 1b)16. In contrast, CL flowers exhibit reduced morphology - retaining only four sepals, two stamens, and two carpels while completely lacking petals - an adaptation ensuring reliable self-pollination under unfavorable conditions (Fig. 1c)16. Consequently, this species provides an ideal model to dissect the gene regulatory networks that drive floral dimorphism and its associated developmental divergence between CH and CL flowers.

Morphology of Pseudostellaria heterophylla. (a) P. heterophylla plant with chasmogamous (CH) and cleistogamous (CL) flowers. Scale bar, 2 cm. (b) Mature CH flower. Scale bar, 3 mm. (c) Mature CL flower tightly enclosed by sepals (left) and CL flower with sepals removed showing stamens and carpels (right). Scale bar, 2 mm.

In recent years, advances in third-generation sequencing and genome assembling technologies have established reference genomes as powerful and fundamental resources for elucidating the genetic mechanisms underlying important biological features of many plants17,18,19,20,21,22. The absence of a reference genome for P. heterophylla has impeded investigations into the genetic basis of both its medicinally valuable compound biosynthesis and unique dimorphic flowering system. To address this critical gap, we assembled and annotated a high-quality chromosome-level reference genome for this species, using short reads, PacBio HiFi long reads, high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) data, and transcriptome data. The final assembly obtained a 2.19 Gb genome with a scaffold N50 of 144.78 Mb. Approximately 99.36% of the genome sequence was anchored to 16 pseudo-chromosomes. Quality assessments of the assembly via Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Ortholog (BUSCO) indicated 97.83% completeness. Repetitive elements constituted 79.41% of the assembled genome, with long terminal repeats being predominant. A total of 37,158 protein-coding genes were identified through a combination of ab initio prediction, homology-based prediction, and transcriptome-based prediction, 87.19% (32,397) of which were functionally annotated. The chromosome-level genome assembly of P. heterophylla provides valuable genetic resources not only for elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying floral dimorphism between CH and CL flowers, but also for advancing our understanding of the biosynthesis of bioactive metabolites in P. heterophylla, facilitating the molecular breeding and genetic improvement for the high-efficiency utilization of this medicinal plant.

Methods

Sample collection and sequencing

Wild-growing P. heterophylla individuals were collected from Kunyu Mountain in Yantai City, Shandong Province, China (37°16′ N, 121°45′ E). These plants were then cultivated under conditions of a 16 h/8 h (day/night) photoperiod at 24 °C with 60% humidity in the greenhouse of Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Fresh young leaves of the same individual were collected for genomic DNA extraction. Multiple tissues, including leaves, stems, flowers (CH and CL flowers), fruits, and roots, were sampled from multiple individuals for transcriptome sequencing. The harvested materials were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80 °C until DNA and RNA extraction.

Genomic DNA was extracted following the modified CTAB method23. The quality of the extracted DNA was examined using a 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and DNA concentration was quantified using a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). For genome survey sequencing, DNA libraries were constructed using Hieff NGS® OnePot Pro DNA Library Prep Kit v4 (Yeasen, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA library quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, USA). The library that passed quality control was then sequenced on DNBSEQ-T7 platform (MGI Tech, China) with a 150-bp paired-end mode, producing 295.85 Gb short-read data (Table 1). For PacBio HiFi sequencing, A SMRTbell (single-molecule real-time) library was prepared using SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and concentration of the final library were examined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Qualified library was sequenced on the PacBio Sequel II system (Pacific Biosciences, USA), generating 68.11 Gb of HiFi long reads (Table 1).

For Hi-C sequencing, fresh leaves were collected from clonally propagated plants (derived from cuttings of a single mother plant) and fixed with formaldehyde to cross-link DNA and proteins. Following the standard protocol, Hi-C libraries were constructed and then assessed for concentration and insert size using Qubit 3.0 and Agilent 2100. The effective concentration of the libraries was accurately determined by qRT-PCR to ensure library quality. The Hi-C library was subsequently sequenced on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform, yielding a total of 238.97 Gb of Hi-C raw data (Table 1).

For transcriptome sequencing, total RNA was isolated independently from five tissue types (leaves, stems, flowers, fruits, and roots) to serve as input material. mRNA was purified from total RNA using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads, then fragmented and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase. The cDNA was processed through end repair, adenylation, and adaptor ligation. Fragments of 370–420 bp were selected using the AMPure XP system, followed by PCR amplification with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase. After purification, the library was quantified using Qubit 3.0, diluted to 1.5 ng/µL, and the insert size was verified. The effective concentration was accurately determined by qRT-PCR to ensure library quality. Qualified libraries were pooled and sequenced on the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform, obtaining a total of 74.77 Gb RNA-seq reads for the subsequent genome annotation analysis (Table 1).

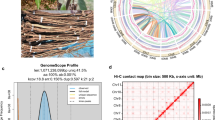

Genome size estimation

To assess the genome size of P. heterophylla, we performed flow cytometry and k-mer analyses. Nuclei for flow cytometry were isolated from fresh P. heterophylla leaves according to a previously described protocol24. Nuclei were stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and their DNA fluorescence was subsequently measured on a MoFlo XDP flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA). Data analysis was conducted using Summit 5.2 software, with only results exhibiting coefficient of variation below 5% considered reliable. Physalis floridana25 was used as the internal standard. The P. heterophylla genome size was then calculated as follows: Reference genome size of P. floridana × (Mean fluorescence of the P. heterophylla G1 peak / Mean fluorescence of the G1 P. floridana peak). This approach yielded an estimated genome size of 2.02 Gb for P. heterophylla. For k-mer analysis, a total of 295.85 Gb raw short reads (135.09 × coverage) were first filtered using fastp v0.23.426 with default parameters to obtain clean reads. Clean reads were then processed by Jellyfish v2.2.1027 to generate a 21-mer frequency distribution, followed by genome characteristics evaluation with GenomeScope v1.028. This analysis estimated the P. heterophylla genome size as approximately 2.08 Gb, consistent with the flow cytometry estimation, and revealed a heterozygosity rate of 0.289% (Fig. 2).

Genome assembly

De novo assembly of the P. heterophylla genome was performed using Hifiasm v0.16.129 with 68.11 Gb PacBio HiFi long reads (31.10 × coverage, Table 1). The primary assembly, a longer and more continuous set of contigs, was extracted from the initial output generated by Hifiasm. To obtain a non-redundant, haplotype-purged assembly, the HiFi reads were realigned to the primary assembly using Minimap2 v2.2430. The resulting alignments were filtered and sorted via SAMtools v1.1331. Then, Purge_haplotigs v1.1.232 was employed to analyze the read coverage depth profile and identify and remove the redundant regions from the sorted alignments. Assembly quality was further assessed using Inspector v1.233, and iterative corrections were implemented based on its error profiles. The resulting draft genome spanned 2.19 Gb, comprising 211 contigs (longest: 166.22 Mb) and a contig N50 of 69.71 Mb.

To further improve the genome assembly continuity and accuracy, Hi-C data were aligned to the draft genome using Juicer v1.634. Subsequent optimization was performed with the 3D-DNA pipeline v18092235 to correct misassemblies and refine contig topology. Manual curation of the raw scaffolds was then conducted in Juicebox v2.20.0036 by examining chromatin interaction patterns to resolve ambiguous contig orientations and placements. Ultimately, 16 pseudochromosomes were unambiguously assembled based on distinct Hi-C interaction signals, covering 99.36% of the genome sequences (Fig. 3). The final chromosome-level assembly of P. heterophylla spans 2.19 Gb with a scaffold N50 of 144.78 Mb (Table 2).

Genome annotation

A comprehensive multi-step strategy was employed to annotate the P. heterophylla genome, including repeat element identification, protein-coding gene prediction, and non-coding RNA prediction. Repeat elements in the genome were annotated using EDTA v2.1.237 pipeline with default parameters, which combines de novo, homology-based, and structural-based methods for comprehensive identification. The “LTR-unknown” sequences from the initial EDTA output were further classified using DeepTE38. In total, 79.41% of the P. heterophylla genome was identified as repetitive sequences. Among these, long terminal repeats (LTRs) were the most predominant (67.30%), followed by terminal inverted repeats (TIRs, 8.55%) (Table 3).

Five types of non-coding RNA, which are microRNA (miRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), small nuclear RNA (snRNA), small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA), and ribosomal RNA (rRNA), were also predicted in the P. heterophylla genome. tRNA prediction was performed using tRNAscan-SE v2.0.1239 with default parameters, while rRNA identification was conducted with barrnap v0.9 (https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap). The remaining non-coding RNAs were annotated using INFERNAL v1.1.540 with the Rfam database41 as reference. This comprehensive analysis identified a total of 22,646 non-coding RNA loci, comprising 102 miRNAs, 7,456 tRNAs, 529 snRNAs, 9,150 snoRNAs, and 5,409 rRNAs (Table 4).

Protein-coding genes prediction was performed by a combination of ab initio prediction, homology-based prediction, and transcriptome-based prediction. For ab initio prediction, Augustus v3.3.342 and SNAP43 were employed with default parameters. For homology-based prediction, the P. heterophylla genome assembly was aligned against the protein sequences of eight highly-annotated species, including Arabidopsis thaliana44, Heliosperma pusillum45, Silene latifolia46, Gypsophila paniculata47, Glycine max48, Vitis vinifera49, Oryza sativa50, and Amborella trichopoda51. For transcriptome-based prediction, transcriptome sequencing data were trimmed using TRIMMOMATIC v0.3652. Clean data were then mapped to the P. heterophylla genome and assembled into transcripts via HISAT2 v2.2.153 and StringTie v2.2.154, following the prediction of open reading frames by TransDecoder v5.7.1 (https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder). Maker3 v2.31.1155 was used to integrate gene models predicted by all methods, resulting in the final gene set. Ultimately, 37,158 protein-coding genes were predicted for the P. heterophylla genome (Table 5). The genomic features were then visualized by circos v0.69-856 (Fig. 4).

The genomic features of Pseudostellaria heterophylla. The features are arranged in the order of chromosomes, GC content, gene density, repeat density, LTR/Copia density, LTR/Gypsy density, and syntenic blocks from outside to inside across the 16 pseudochromosomes. Syntenic blocks among inter-chromosome were identified by MCScanX70 with default parameters.

Function annotation of these predicted genes was conducted via a two-step approach. Initially, the eggNOG-mapper v2.1.1357 software was applied to align those gene sequences to the eggNOG v5.0 database58, which successfully annotated 30,851 (83.03%) of the gene set. Among these, 28,630 were assigned Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) categories, 14,271 were annotated with Gene Ontology (GO) terms, and 9,598 were linked to pathways from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). Additionally, motifs and domains were identified using InterProScan v5.75-106.059 to compare with the InterPro member databases. This analysis revealed that 30,533 proteins (82.17%) contained conserved domains, with 26,819, 23,456, 18,562, and 17,487 proteins annotated in the PANTHER60, Pfam61, Gene3D62, and SUPERFAMILY63 databases, respectively. Overall, 32,395 (87.18%) of the predicted protein-coding genes were functionally annotated in at least one of these databases (Table 5).

Data Records

The short reads, PacBio HiFi reads, Hi-C reads, and RNA-seq reads have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) of the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) under the accession number CRA02847764. The final P. heterophylla genome assembly has been deposited in European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) with the accession number GCA_977035685.165. The genome annotation files are available in Figshare66.

Technical Validation

Assembly quality and completeness were evaluated through three complementary approaches. Firstly, the filtered short reads were mapped back to the final P. heterophylla genome via Bowtie2 v2.3.4.167, achieving 96.74% mapping rate and 99.90% genome coverage. Secondly, the base-level accuracy of the genome assembly was assessed by Merqury v1.368, based on 21-mers derived from DNBSEQ-T7 sequencing short reads. This analysis yielded a consensus quality value of 53.67, which means an extremely low error rate of 4.29 × 10−8. Thirdly, BUSCO v5.7.169 analysis against the embryophyta_odb10 dataset was employed, revealing 97.83% complete BUSCOs (90.71% single-copy, and 7.12% duplicated), along with 0.93% fragmented and 1.24% missing BUSCOs. These results collectively confirm a high-quality genome assembly for P. heterophylla.

The predicted proteins were evaluated by BUSCO v5.7.169 with the embryophyta_odb10 dataset. Among a total of 1,614 BUSCOs, 1,555 (96.34%) BUSCOs were complete (1,452 single-copy BUSCOs and 103 duplicated BUSCOs), 15 (0.93%) BUSCOs were fragmented and 44 (2.73%) BUSCOs were missing, which indicated high-quality annotation of the predicted gene models.

Code availability

No custom codes were used in this study. All bioinformatics tools and software were executed with default parameters unless otherwise specified in the Methods section.

References

Hu, D., Shakerian, F., Zhao, J. & Li, S. Chemistry, pharmacology and analysis of Pseudostellaria heterophylla: a mini-review. Chin. Med. 14, 14–21 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. Chemical properties, preparation, and pharmaceutical effects of cyclic peptides from Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Molecules 30, 2521 (2025).

Pang, W., Lin, S., Dai, Q., Zhang, H. & Hu, J. Antitussive activity of Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax extracts and improvement in lung function via adjustment of multi-cytokine levels. Molecules 16, 3360–3370 (2011).

Rui, G. et al. Protective effects of Radix Pseudostellariae extract against retinal laser injury. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 33, 1643–1653 (2014).

Choi, Y. Y. et al. Immunomodulatory effects of Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miquel) Pax on regulation of Th1/Th2 levels in mice with atopic dermatitis. Mol. Med. Rep. 15, 649–656 (2017).

Sheng, R. et al. Polysaccharide of Radix Pseudostellariae improves chronic fatigue syndrome induced by Poly I:C in mice. Evid. Based Compl. Alt. 2011, 840516 (2011).

Sha, M. et al. Comparative chemical characters of Pseudostellaria heterophylla from geographical origins of China. Chin. Herb. Med. 15, 439–446 (2023).

Tantai, J., Zhang, Y. & Zhao, H. Heterophyllin B inhibits the adhesion and invasion of ECA-109 human esophageal carcinoma cells by targeting PI3K/AKT/β-catenin signaling. Mol. Med. Rep. 13, 1097–1104 (2016).

Chen, C. et al. Heterophyllin B an active cyclopeptide alleviates dextran sulfate sodium‐induced colitis by modulating gut microbiota and repairing intestinal mucosal barrier via AMPK activation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 66, 2101169 (2022).

Shi, W. et al. Protective effects of heterophyllin B against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice via AMPK activation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 921, 174825 (2022).

Yang, Z. et al. Heterophyllin B, a cyclopeptide from Pseudostellaria heterophylla, enhances cognitive function via neurite outgrowth and synaptic plasticity. Phytother. Res. 35, 5318–5329 (2021).

Qin, X. et al. Identification of a key peptide cyclase for novel cyclic peptide discovery in Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Plant Commun 6, 101315 (2025).

Zheng, W. et al. The biosynthesis of heterophyllin B in Pseudostellaria heterophylla from prePhHB-encoded precursor. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1259 (2019).

Plitmann, U. Distribution of dimorphic flowers as related to other elements of the reproductive strategy. Plant Species Biol. 10, 53–60 (1995).

Culley, T. M. & Klooster, M. R. The cleistogamous breeding system: a review of its frequency, evolution, and ecology in angiosperms. Bot. Rev. 73, 1–30 (2007).

Luo, Y., Bian, F. H. & Luo, Y. B. Different patterns of floral ontogeny in dimorphic flowers of Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Caryophyllaceae). Int. J. Plant Sci. 173, 150–160 (2012).

He, Q. et al. The near‐complete genome assembly of Reynoutria multiflora reveals the genetic basis of stilbenes and anthraquinones biosynthesis. J. Syst. Evol. 62, 1085–1102 (2024).

Xie, J. et al. A chromosome-scale reference genome of Aquilegia oxysepala var. kansuensis. Hortic. Res. 7, 113 (2020).

Ma, J. et al. Chromosome‐scale genomes of Toona fargesii provide insights into competency of root sprouting. J. Syst. Evol. 63, 567–582 (2025).

Qin, L. et al. Insights into angiosperm evolution, floral development and chemical biosynthesis from the Aristolochia fimbriata genome. Nat. Plants 7, 1239–1253 (2021).

Wang, K. et al. The chromosome-level genome of Hemiboea subcapitata provides new insights into karst adaptation. J. Syst. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.70007 (2025).

Xie, L. et al. Technology-enabled great leap in deciphering plant genomes. Nat. Plants 10, 551–566 (2024).

Allen, G. C., Flores-Vergara, M. A., Krasynanski, S., Kumar, S. & Thompson, W. F. A modified protocol for rapid DNA isolation from plant tissues using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2320–2325 (2006).

Doležel, J., Greilhuber, J. & Suda, J. Estimation of nuclear DNA content in plants using flow cytometry. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2233–2244 (2007).

Lu, J. et al. The Physalis floridana genome provides insights into the biochemical and morphological evolution of Physalis fruits. Hortic. Res. 8, 244 (2021).

Chen, S. Ultrafast one‐pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using fastp. iMeta 2, e107 (2023).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011).

Vurture, G. W. et al. GenomeScope: fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics 33, 2202–2204 (2017).

Cheng, H. et al. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Li, H. & Alkan, C. New strategies to improve minimap2 alignment accuracy. Bioinformatics 37, 4572–4574 (2021).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 10, giab008 (2021).

Roach, M. J., Schmidt, S. A. & Borneman, A. R. Purge Haplotigs: allelic contig reassignment for third-gen diploid genome assemblies. BMC Bioinformatics 19, 460 (2018).

Chen, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, A. Y., Gao, M. & Chong, Z. Accurate long-read de novo assembly evaluation with Inspector. Genome Biol. 22, 312 (2021).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Systems 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Systems 3, 99–101 (2016).

Ou, S. et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol. 20, 275 (2019).

Yan, H., Bombarely, A. & Li, S. DeepTE: a computational method for de novo classification of transposons with convolutional neural network. Bioinformatics 36, 4269–4275 (2020).

Chan, P. P., Lin, B. Y., Mak, A. J. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 9077–9096 (2021).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

Kalvari, I. et al. Non‐coding RNA analysis using the Rfam database. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 62, e51 (2018).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W435–W439 (2006).

Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5, 59 (2004).

Lamesch, P. et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1202–D1210 (2012).

Szukala, A. et al. Polygenic routes lead to parallel altitudinal adaptation in Heliosperma pusillum (Caryophyllaceae). Mol. Ecol. 32, 1832–1847 (2023).

Yue, J. et al. The origin and evolution of sex chromosomes, revealed by sequencing of the Silene latifolia female genome. Curr. Biol. 3, 2504–2514 (2023).

Li, F. et al. The chromosome-level genome of Gypsophila paniculata reveals the molecular mechanism of floral development and ethylene insensitivity. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac176 (2022).

Xie, M. et al. A reference-grade wild soybean genome. Nat. Commun. 10, 1216 (2019).

Velasco, R. et al. A high quality draft consensus sequence of the genome of a heterozygous grapevine variety. PLoS ONE 2, e1326 (2007).

Ouyang, S. et al. The TIGR Rice Genome Annotation Resource: improvements and new features. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D883–D887 (2007).

Amborella Genome Project. The Amborella genome and the evolution of flowering plants. Science 342, 1241089 (2013).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360 (2015).

Li, J., Shumate, A., Wong, B., Pertea, G. & Pertea, M. Improved transcriptome assembly using a hybrid of long and short reads with StringTie. PLoS Comput. Biol. 18, e1009730 (2022).

Campbell, M. S., Holt, C., Moore, B. & Yandell, M. Genome annotation and curation using MAKER and MAKER‐P. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 48, 4.11.1–4.11.39 (2014).

Krzywinski, M. et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19, 1639–1645 (2009).

Cantalapiedra, C. P. et al. eggNOG-mapper v2: functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 5825–5829 (2021).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D309–D314 (2019).

Finn, R. D. et al. InterPro in 2017—beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D190–D199 (2017).

Mi, H. et al. PANTHER version 16: a revised family classification, tree-based classification tool, enhancer regions and extensive API. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D394–D403 (2021).

El-Gebali, S. et al. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D427–D432 (2019).

Lewis, T. E. et al. Gene3D: extensive prediction of globular domains in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D435–D439 (2018).

Wilson, D. et al. SUPERFAMILY–sophisticated comparative genomics, data mining, visualization and phylogeny. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D380–D386 (2009).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA028477 (2025).

European Nucleotide Archive https://identifiers.org/insdc.gca:GCA_977035685.1 (2025).

Xu, G. Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation files of Pseudostellaria heterophylla. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29672696 (2025).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Rhie, A. et al. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 21, 245 (2020).

Manni, M. et al. BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4647–4654 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e49 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Science & Technology Fundamental Resources Investigation Program (2024FY100703).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.J., G.X., B.H. and Y.X. designed the research. F.L., M.W. and H.L. collected the samples. Y.X. and B.H. analyzed the data. Y.J., G.X. and Y.X. wrote the manuscript. Y.X. and B.H. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, Y., Han, B., Liu, F. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the traditional Chinese medical plant Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Sci Data 13, 107 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06423-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06423-5